The coronavirus pandemic, which originated in Wuhan, China, has spread throughout the world. Beginning in March 2020, California issued the first stay-at-home orders, with other states following suit.Footnote 1 With widespread orders to stay-at-home and social distance in public spaces to help contain the spread, the pandemic has impacted the lives of everyone in the United States.

During the early stages of the pandemic, political elites such as former president Trump linked Asian Americans to the virus, resulting in an anti-Asian atmosphere characterized by social exclusion. Even though Trump had already made some connection between the coronavirus and China in January and February, he did this more explicitly in March 2020, as confirmed coronavirus cases in the United States began to surge that month. Trump doubled down on this rhetoric even after receiving criticism for his and his administration’s early response to the pandemic, or lack thereof. Even though the World Health Organization (WHO) warns against naming or associating diseases with racial characteristics,Footnote 2 Trump continued to use racialized COVID-19 terms. Subsequently, other members of the GOP (the Republican Party) followed suit.Footnote 3 As a result, Trump strengthened the explicit association between the coronavirus to Chinese Americans, and this connection has also extended to non-Chinese Asian Americans as well.

The more explicit association of Asian Americans to the virus has come at a cost. Even though violence and racism against Asian Americans is not new,Footnote 4 the coronavirus pandemic has brought forth a renewed wave of anti-Asian bias, which stems from elite-level associations of the virus with Asians. Across the country, Asian Americans have reported a surge in harassment and hate crimes on the basis of their race (Margolin Reference Margolin2020). The website Stop AAPI [Asian American Pacific Islander] Hate Footnote 5 recorded nearly 1,500 incidents of anti-Asian hate incidents in one month (Jeung and Nham Reference Jeung and Nham2020). A year later, the same organization reported an increase totaling 3,795 anti-Asian hate incidents. These racist incidents are also not limited to Chinese Americans, but to other Asian Americans (such as Filipino, Thai, and Korean Americans) as well (Jeung et al. Reference Jeung, Horse, Popovic and Lim2021). Racialized, targeted language by elites, such as calling groups a “disease” or a “cancer,” violates norms of tolerance. When elites engage in this behavior, the mass public follows suit (Zaller Reference Zaller1992; Lenz Reference Lenz2013; Broockman and Butler Reference Broockman and Butler2017). We extend this work on elites’ “emboldening effect” (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Merolla, Shah, Lemi, Collingwood and Ramakrishnan2019) to Asian Americans, particularly paying attention to how Trump’s rhetoric creates an atmosphere where it is socially acceptable to express and act on anti-Asian sentiment.

We situate this project in the broader literature on elite-driven messaging, social exclusion, and Asian American partisanship. We examine how Trump’s labeling of the virus as the “China virus” has contributed to anti-Asian sentiment in broader U.S. society, and how that messaging has also impacted Asian Americans’ partisan attitudes. We argue that Trump’s anti-Asian rhetoric, using the coronavirus as a driver, contributes to social exclusion of Asian Americans and pushes Asian Americans to lean more towards the Democratic Party. In a preview of our findings, we use Twitter data to track the spread of anti-Asian views in the United States. Analysis of 1.4 million tweets shows how Trump has racialized the public health crisis by popularizing racially charged COVID-19 terms such as the “Kung flu” and how anti-Asian attitudes have increased since the outbreak of COVID-19. We then utilize repeated, cross-sectional surveys over time to measure changes in partisan attitudes among Asian Americans as Trump and the GOP’s rhetoric bears onward. Analysis of 12,907 Asian American survey respondents indicates that Trump’s exclusionary rhetoric has motivated more favorability toward the Democratic Party. In contrast, these same partisan attitudes have not changed as much or as consistently for Whites, Blacks, and Latino/as. This lean toward the Democratic Party is important for a community that has been traditionally less likely to label themselves in partisan terms (Hajnal and Lee Reference Hajnal and Lee2011; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Ramakrishnan, Lee and Junn2011). As Trump and other elites continue to consistently frame COVID-19 in anti-Asian terms, the social exclusion that Asian Americans encounter as a result may further cement this group with the Democratic Party.

Elite Messaging, Social Exclusion, and Asian American Partisan Attitudes

Elites and the frames, which they can elect to use, shape mass public opinion. This is the case when discussing various policy issues (Zaller Reference Zaller1992; Druckman Reference Druckman2001), particularly when it comes to welfare (Rose and Baumgartner Reference Rose and Baumgartner2013; Schneider and Jacoby Reference Schneider and Jacoby2005; Gilens Reference Gilens1999), healthcare (Tesler Reference Tesler2012), and immigration (Haynes, Merolla, and Ramakrishnan Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016; Pérez Reference Pérez2015). Although norms of equality have made racial “dog whistles” and explicit racial appeals socially undesirable (Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001; Valentino, Hutchings, and White Reference Valentino, Hutchings and White2002), there has been a notable increase in the usage of inflammatory racially charged rhetoric by Trump and the Republican Party within the last few years (Costello Reference Costello2016). Trump’s provocations have been found to embolden supporters to act on their racial prejudices. For example, Trump’s Twitter usage corresponded with an increase in anti-Muslim hate crimes in 2016 (Müller and Schwarz Reference Müller and Schwarz2020). Additionally, through a series of experiments, Newman et al. (Reference Newman, Merolla, Shah, Lemi, Collingwood and Ramakrishnan2019) find that exposure to racist elite speech regarding Latino immigrants increases the likelihood of an individual acting on their prejudices and engaging in discriminatory interpersonal acts. This “emboldening effect” occurs when political elites embrace racism and bias; this is a clear example of how elite racist rhetoric encourages discriminatory behavior at the mass level.

Asian Americans also present an interesting puzzle in the study of partisanship. At a superficial level, many Asian Americans have high median incomes, tend to identify as Evangelical Christians, or immigrated to the United States fleeing communism, traits which are typically associated with voting Republican (Gelman, Kenworthy, and Su Reference Gelman, Kenworthy and Su2010; Gelman Reference Gelman2010).Footnote 6 Despite these traits, Asian Americans have trended Democratic in the last few election cycles—65% voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016 and 73% voted for Barack Obama in 2012. In comparison, only about 31% of Asian Americans voted for Bill Clinton in 1992 (Fuchs Reference Fuchs2016). For the most recent presidential election, Ghitza and Robinson (Reference Ghitza and Robinson2021) estimate that 67% of AAPIs voted for the Democratic candidate. This preference for the Democratic Party, despite traditionally Republican predispositions, may be due to perceptions of Republicans as ideologically extreme, liberalizing peer-to-peer socialization at school, and a preference for living in liberal urban areas in the United States (Raychaudhuri Reference Raychaudhuri2018, Reference Raychaudhuri2020).Footnote 7

Despite a tendency to vote for Democrats, Asian Americans are not as likely to explicitly identify with a party. Instead, a significant proportion of Asian Americans prefer to list themselves as “Independent” or “non-partisan” (Hajnal and Lee Reference Hajnal and Lee2011; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Ramakrishnan, Lee and Junn2011). Partisan identification is important because individuals who identify with a party are much more likely to vote than those who are unaffiliated (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960, Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1966). Taken together, partisan preferences among Asian Americans are less stable relative to those of Whites and African Americans. If experiences with coronavirus-related exclusion, which stem from elite rhetoric, lead Asian Americans to be more solidified in their partisan identification, this may contribute to increased political participation and civic engagement at the polls and beyond.Footnote 8

We also aim to focus specifically on the experiences of Asian Americans during times of pandemic. Anti-Asian sentiment has been present in the United States since the late nineteenth century, and animosity towards Asian Americans is not new (Kim Reference Kim1999; Junn Reference Junn2007). Historically, Asian Americans were thought of as economic and cultural invaders to the U.S., a fear known as the “yellow peril.” This fear contributed to racially motivated murders, lynching, and racist legislation such as the Page Act and Chinese Exclusion Act (Nguyen, Carter, and Carter Reference Nguyen, Carter and Carter2019). In addition, Asian Americans were also thought to be disease-bearing, unsanitary, and the cause of outbreaks on the West Coast (Trauner Reference Trauner1978). This association of Asian Americans with disease resurfaced in the 2002–2004 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak and recently during the COVID-19 pandemic, with popular news media associating outbreaks with “unsanitary wet markets” and the consumption of “bats, snakes, and dogs.”Footnote 9 This plays into long-standing associations of Asians and Asian Americans as foreign and diseased. In the present day, Asian Americans are thought of as “competent” yet “cold” individuals who are stereotyped as intelligent and high achieving, yet non-American and unassimilable (Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017; Fiske Reference Fiske2018; Cheryan and Monin Reference Cheryan and Monin2005). Despite the pervasive stereotype of Asian Americans as “near White” or the “model minority,” COVID-19 has laid bare the perpetual alien-ness of Asian Americans (Hua and Junn Reference Hua and Junn2021).

According to the Pew Research Center, Asian Americans are also more likely to note that they are targets of discrimination than Latina/os and Whites (Budiman and Ruiz Reference Budiman and Ruiz2021). Some have found that discrimination, whether personally experienced or inflammatory rhetoric communicated by leaders, influences various political behavior outcomes and beliefs (Leung and Song Reference Leung and Song2021; McClain et al. Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Walton and Watts2009; Oskooii Reference Oskooii2018; Newman et al. Reference Newman, Merolla, Shah, Lemi, Collingwood and Ramakrishnan2019). We further argue within this line of scholarship that Trump’s racialized rhetoric contributes to a climate of social exclusion for Asian Americans. As Newman et al. (Reference Newman, Merolla, Shah, Lemi, Collingwood and Ramakrishnan2019) find, Trump’s racist rhetoric emboldens supporters to act upon prejudiced beliefs, which would have otherwise been seen as socially undesirable. The COVID-19 pandemic has also come with a staggering increase in anti-Asian hate crimes, vandalism, and harassment (Jeung et al. Reference Jeung, Horse, Popovic and Lim2021; Wong Reference Wong2021; Tessler, Choi, and Kao Reference Tessler, Choi and Kao2020; see also Arora and Kim Reference Arora and Kim2020). The perception of Asian Americans as foreigners makes it easy to justify anti-Asian attitudes and blame Asian Americans for “importing” the coronavirusFootnote 10 (Liu Reference Liu2020). Taken together, we argue that inflammatory elite rhetoric contributes to very salient societal exclusion of Asian Americans during the coronavirus pandemic.

Further, these feelings of social exclusion have unique consequences on the partisan leanings of Asian Americans. The concept of social exclusion draws from group-based (i.e., societal) and individual (i.e., psychological) work wherein individuals who are rejected or excluded by society associate exclusion with certain political groups. Evidence has shown that individuals generally view the Democratic Party as more favorable towards minorities (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1989; Hajnal and Horowitz Reference Hajnal and Horowitz2014). Even if minority individuals do not feel wholly included in the Democratic Party, they are aware that the Republican Party excludes them on the basis of their racial and ethnic group membership. As experienced on an interpersonal level, social exclusion leads Asian Americans to be more favorable towards the Democratic Party (Kuo, Malhotra, and Mo Reference Kuo, Malhotra and Mo2017). The Republican Party has also become increasingly viewed as ethnocentric and catering to White Americans (Kinder Reference Kinder2013). Thus, this ethnocentrism leads Asian Americans, who would otherwise be thought of as Republican-leaning due to socioeconomic status, to identify more with the Democratic Party. Drawing on previous scholarship on social exclusion and Asian Americans, particularly from Kuo, Malhotra, and Mo (Reference Kuo, Malhotra and Mo2017), we extend this work to the coronavirus crisis and Asian American partisan attitudes. Trump’s anti-Asian remarks surrounding the coronavirus shape an environment characterized by social exclusion, where Asian Americans are targeted on the basis of racial group membership. This results in increased favorability toward the Democratic Party. Given the negative GOP racial rhetoric (elite emboldening) and increase in self-reported anti-Asian harassment (interpersonal social exclusion), Asian Americans may associate these incidents with the Republican Party, thus driving Asian Americans more toward the Democratic Party instead.

Hypotheses

We utilize two data sources in order to test our theoretical expectations. First, we use 1.4 million tweets related to COVID-19 over time as a measurement of anti-Asian societal level exclusion due to Trump’s inflammatory comments. Next, we measure shifts in partisan attitudes over time using repeated cross-sectional weekly surveys, analyzing a total of 12,907 Asian Americans.

Using Twitter data in Study 1, we track the rise of anti-Asian sentiment in the United States. We expect to see the following two patterns from this social media data:

H1a: Trump’s rhetoric has popularized racially charged COVID-19 terms such as the “Wuhan virus,” “Chinese virus,” and “Kung flu.”

H1b: Anti-Asian attitudes have increased since the spread of COVID-19 in the United States.

Using the survey data in Study 2, we investigate changes in partisan attitudes among Asian Americans. We expect to see the following two patterns in the survey data:

H2a (temporal change): Trump’s anti-Asian and social exclusionary rhetoric has increased favorability toward the Democratic Party, the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate at the time (Joe Biden), and partisan identification with the Democratic Party among Asian Americans.

H2b (cross-sectional variation): Trump’s anti-Asian and social exclusionary rhetoric pushes Asian Americans most consistently to lean more Democratic relative to Whites, Latina/os, and African Americans.

Study 1: Social Media Analysis

Data and Methods

We identify the extent to which Trump made derogatory terms such as the “Chinese virus” popular and trace how anti-Asian attitudes have increased in the United States since the pandemic by analyzing more than one million COVID-19-related tweets. We expect that anti-Asian bias and attitudes are present in the United States among the general public but have increased during the spread of the coronavirus. We expect that Trump’s usage of racially charged terms to be associated with an increase in the usage of the same terms in the digital public sphere.

Our first goal is to estimate changes in anti-Asian sentiment among the general public. The data source we utilize is the large-scale COVID-19 Twitter chatter dataset (v.15) created by Panacealab.Footnote 11 These tweets were created between January and June 2020, and the number of those tweets composed in English was more than 59 million. We randomly selected 10% of these tweets, stratifying by months in which these tweets were created. We then identified tweets specifically created by Twitter users located in the United States. The number of tweets in the final dataset amounts to 1,394,468. We also developed an R package which helps other researchers wrangle the large-scale Twitter data with little technical expertise on such data.Footnote 12

Tracing keyword trends. COVID-19 has many names. COVID-19 and coronavirus are epidemiological terms used by the scientific community; other colloquial terms such as “Chinese virus,” “Wuhan virus,” and especially “Kung flu” are racially charged terms. The colloquial terms were popularized by the Trump administration and are negatively associated with Chinese/Asian communities. This contributes to social exclusion.

We first trace the trends of several racially charged terms and anti-racism-related terms, such as “Racist,” “Racism,” and “Anti-Asian” among COVID-19-related tweets created by users in the United States. We use both categories to differentiate those tweets targeting Asian Americans from other tweets opposing these anti-Asian attitudes. We then replicate this analysis using Google search-trends data to strengthen external validity as Twitter users are not wholly representative of the U.S. population. This is because people do not create Twitter accounts randomly. Moreover, we are only analyzing a subset of Twitter users who tweeted about COVID-19. Therefore, it is important to demonstrate that the keyword trends, which we identified using the Twitter data, are not limited to that particular social media platform and dataset. For these reasons, we run the same data analysis using Google search API (Application Programming Interface). Although the Google search data is not collected via random sampling, Google search is more representative of the general population due to the accessibility of Google and its wider user base.

Tracing changes in topic model proportions. The Twitter and Google data analysis is effective at examining how Trump’s speech popularized racially charged COVID-19 terms. However, if we take a look at the proportions of the tweets mentioning “Chinese virus,” “Kung flu,” and “Wuhan virus” (refer to figure A.1 in online appendix A), they were extremely marginal. Only 0.5% of the tweets mentioned these racially charges COVID-19 terms. In contrast, the proportions of the tweets that mentioned Asian, Chinese, or Wuhan were twenty times larger. Therefore, if we trace the rise of anti-Asian sentiment on social media exclusively focusing on these keyword trends, the conclusion we draw from the data analysis could be strongly biased.

However, analyzing the tweets related to Chinese or Wuhan is challenging because, in this case, what the keywords imply is not obvious. If someone tweeted “Chinese virus” or “Kung flu,” the political and racial context is relatively clear. However, if someone tweeted about “COVID-19” and “China,” it could be about the country, the virus, anti-Asian sentiment, or something else. In other words, many latent themes exist within these tweets. We needed a way to distinguish these themes to make an inference about these tweets. In order to go beyond keywords and try to analyze deeper textual contexts, we employ a machine-learning technique known as topic modeling. We assume that these themes (or topics) are clusters of tweets, and we can identify these topics based on how words in different tweets co-occur. Using the “stm” package in R (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Stewart and Tingley2014), we find that, in this case, three topics would be optimal given the trade-off between exclusivity and semantic coherence (refer to figure A.2 in online appendix A). Topic modeling does not give us any specific meaning behind what the estimated topics are about. In order to learn what these topics are about substantively, researchers might read some samples of these topics and make subjective decisions. This aspect of topic modeling is time-consuming and could lead to post-hoc theorizing. To avoid this problem, we used a topic modeling method called keyword assisted topic models (keyATM) that was recently developed by Eshima, Imai, and Sasaki (Reference Eshima, Imai and Sasaki2020). This helps us leverage a small number of keywords to generate a better classification schema that makes for easier interpretation. KeyATM is especially applicable to tweets, as Twitter hashtags are literally keywords. We extracted hashtags of the tweets that mentioned COVID-19 and either “Asian,” “Chinese,” or “Wuhan,” and visualized them using a word cloud in figure 1.Footnote 13 Based on the hashtags, we created two lists of words: anti-Asian (sentiment) and anti-racism.Footnote 14 Figure A.4 in online appendix A shows the relative frequency of these keywords in the corpus by topic. Using these lists, we run keyword topic modeling and estimated topic proportions in the Twitter data and also traced how these proportions changed over time (dynamic topic modeling).Footnote 15

Figure 1 Hashtags of tweets mentioning “COVID-19” and either “Asian,” “Chinese,” or “Wuhan”

Results

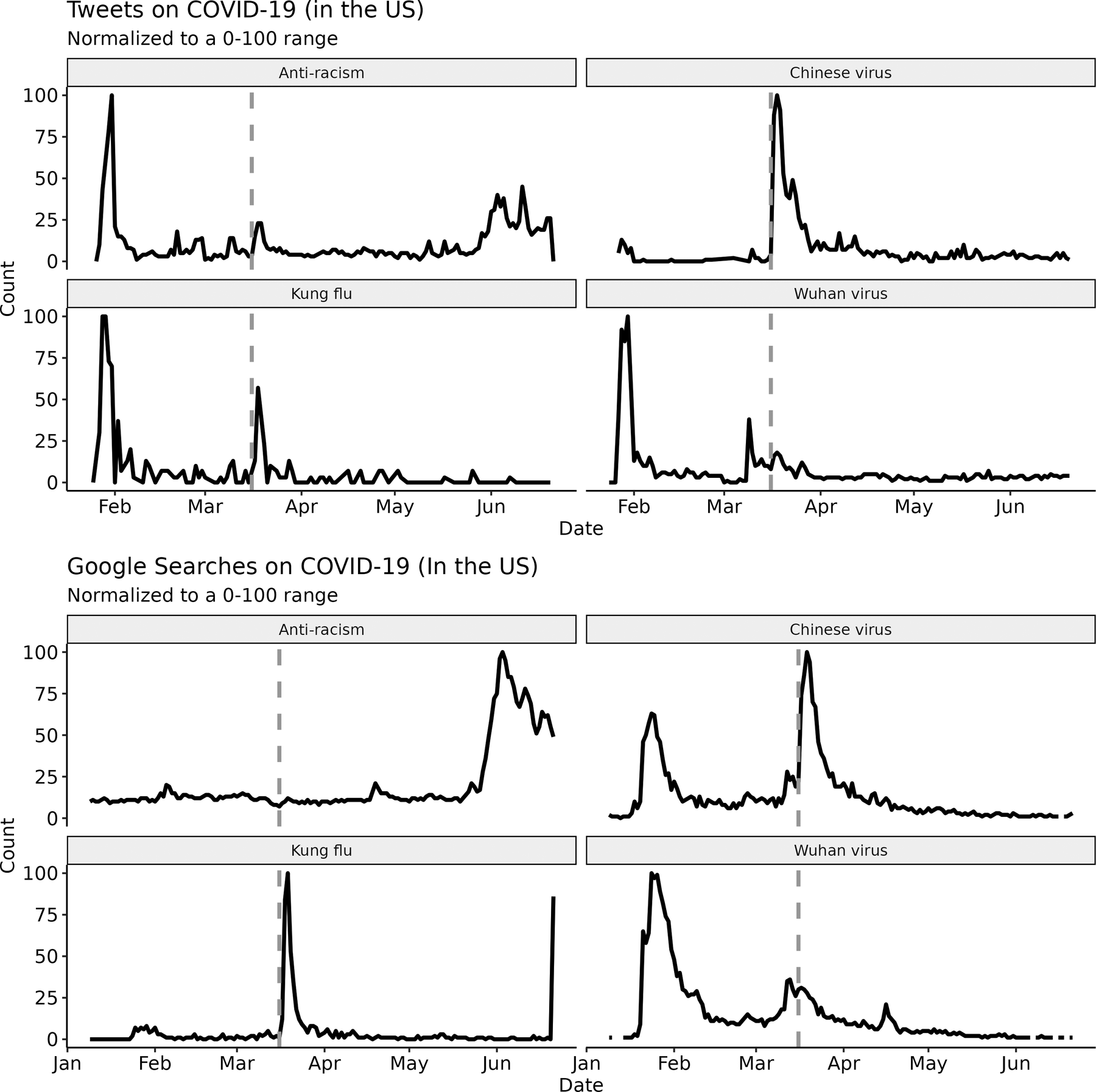

Keyword analysis. Our keyword analysis shows that Trump’s rhetoric popularized racially charged COVID-19 terms. The top panel in figure 2 shows the trends of racially charged COVID-19 and anti-racism-related terms among the COVID-19-related tweets created by users in the United States. The X-axis indicates when these tweets were created and the Y-axis represents the count of these tweets normalized to a 0–100 range. The dark gray dashed line indicates when President Trump first referred to COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus.” We find that “Wuhan virus,” “Kung flu,” and “anti-racism” were already popular terms among Twitter users in February 2020. This evidence shows that anti-Asian sentiment was present even before Trump made his anti-Asian rhetoric in March. However, Trump’s role in strengthening anti-Asian rhetoric was also apparent. These terms’ popularity on Twitter and Google search was fading until Trump used them in public speeches. Moreover, Trump’s remarks made another derogatory term “Chinese virus” trend on Twitter, although their increasing rates varied to some extent. Whereas the number of tweets on “Kung flu,” and “Wuhan virus” resurged relatively modestly, the tweets on “Chinese virus” increased exponentially.

Figure 2 Comparison between Google search and Twitter trends

In the bottom panel in figure 2, we also analyzed the Google search trends using a similar method to strengthen external validity. The bottom panel of figure 2 demonstrates that Twitter and Google trends are in parallel to a large extent. “Chinese flu” and “Wuhan virus” trended in January and February 2020. Nevertheless, their popularity soon decreased substantially. After Trump referred to COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus,” Google users paid more substantive attention to “Chinese flu” as well as “Kung flu” and, to a lesser degree, “Wuhan virus.” The results alleviate concerns about external validity.

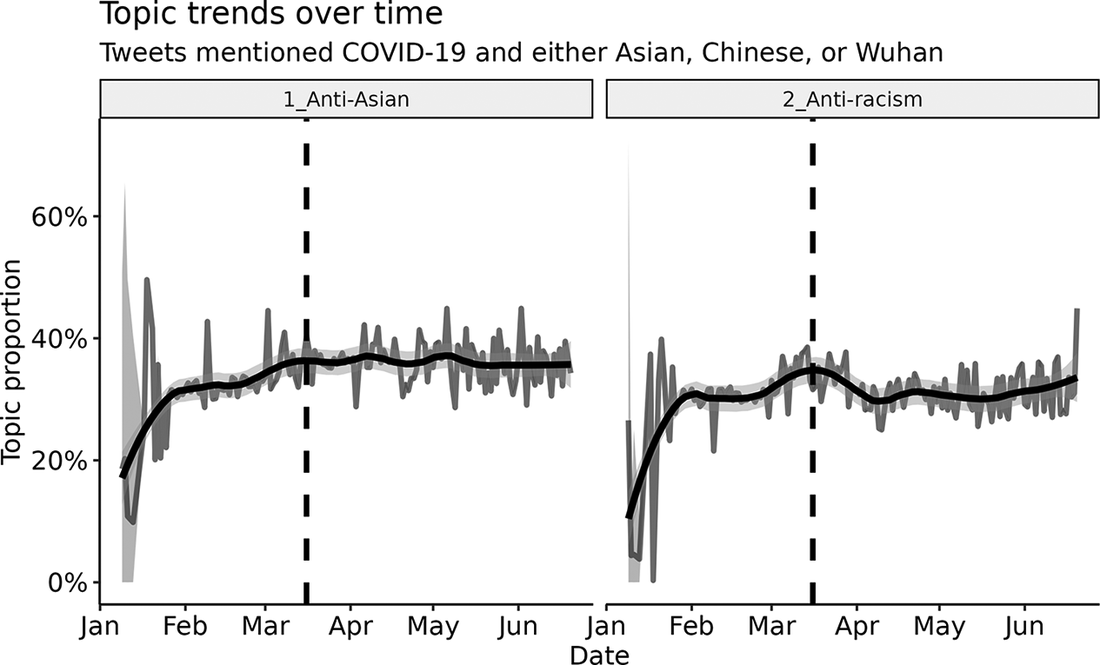

Topic Modeling Analysis. Next, we turn to topic modeling. Here, the data are limited to the tweets that mentioned COVID-19 and either “Asian,” “Chinese,” or “Wuhan.” Anti-Asian is a topic that represents tweets mentioning something negative about Asians. Anti-racism is a topic that represents tweets that oppose such anti-Asian attitudes.

The base topic modeling result (figure A.3 in online appendix A) shows that the proportions of anti-Asian and anti-racism topics are slightly above 30% in the corpus and close to each other (34% and 33%, respectively). The dynamic topic modeling in figure 3 shows that the proportions of both anti-Asian and anti-racism topics in the corpus surged in January when COVID-19 began to spread in the United States. This pattern is consistent with figure 2. The Twitter and Google data show that some anti-Asian terms were already popular in January and February. These anti-Asian terms were present even before Trump first framed the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus” in March. After Trump’s initial comment, though, these anti-Asian terms spiked again in popularity.

Figure 3 Dynamic topic modeling analysis results

Further, how Trump normalized this rhetoric is critical. Figure 2 shows that anti-Asian keywords were losing popularity on the Twitter platform until Trump revitalized references to the “Chinese virus.” Trump racialized COVID-19 by referring to it as the Chinese virus, and he did so repeatedly and consistently. While Trump did not initiate anti-Asian sentiment, he helped to sustain it. In addition, Trump’s framing of COVID-19 as the Chinese virus matters because it creates a more explicit connection between the virus and a particular racial/ethnic group (Tversky and Kahneman Reference Tversky and Kahneman1981; Gilens Reference Gilens1999; Lakoff Reference Lakoff2014). As other GOP elites also began to follow suit, this shaped an environment characterized by social exclusion within the mass public, especially for the targeted group—Asian Americans. Specifically, political elites’ normalization of anti-Asian attitudes is problematic because many researchers have found a linkage between anti-Asian attitudes and hate crimes, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic (Lu and Sheng Reference Lu and Sheng2020). Trump, a prominent political elite, signaled to the mass public that such terms are acceptable and that anti-Asian bias was therefore justified. As more GOP elites and masses evoked and reinforced the racialized frame by either adopting or criticizing the racially charged COVID-19 terms, anti-Asian rhetoric became normalized and accepted as part of the everyday conversation regarding the pandemic. Our next goal is to assess how this elite-driven social exclusion in the masses shapes the partisan attitudes of Asian Americans.

Study 2: Survey Data Analysis

To measure partisan changes over time among Asian Americans, we use repeated cross-sectional surveys from Nationscape conducted by Democracy Fund and Principal Investigators at UCLA (Tausanovitch and Vavreck Reference Tausanovitch and Vavreck2020).Footnote 16 Nationscape is a weekly online survey of approximately 6,250 respondents, inclusive of Latina/os, Whites, African Americans, and Asian Americans. We leverage survey data on partisan attitudes between July 2019–May 2020, before and after Trump begins to frame COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus.” We analyze how his rhetoric has shaped individuals’ partisan attitudes across race through May 7, 2020 (access to survey data ended on this date at the time of writing this article). We examine a total of n=284,078 surveys across racial groups: Asian Americans (n=12,907); African Americans (n=32,464); Latina/os (n=38,549); and Whites (n=200,158). Purposive sampling, selecting respondents based upon their characteristics, is used to obtain a sample that is constructed to be representative of the population. As with Reny (Reference Reny2020), survey weights have been applied to accurately represent the population of interest.Footnote 17 This data has been weighted by gender, census region, race, education, age, household language, and country of birth, comparing responses to the 2018 American Community Survey.Footnote 18

We expect that Trump’s anti-Asian rhetoric and further social exclusion has contributed to an increase in Asian Americans’ favorability toward the Democratic Party, the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee at the time (Joe Biden),Footnote 19 as well as an increase in Democratic Party identification. First, we look at the data over time to see how Asian Americans have shifted in their partisan opinions. We then compare favorability toward the Democratic Party, its presidential candidate, and party identification before and after March 16, 2020, the date when Trump began to frame the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus.”Footnote 20 Finally, we compare these shifts in Asian American partisan attitudes to those of Latina/os, Blacks, and Whites.

We then conduct a pooled cross-sectional analysis of weekly surveys across each racial group to analyze how social exclusion uniquely influences the partisan attitudes of Asian Americans, relative to African Americans, Latina/os, and Whites.Footnote 21 We run regression models where our main independent variable of interest is an indicator for whether respondents completed their survey prior to March 16, 2020, before Trump’s framing of COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus” (0), or after March 16, 2020, following this frame (1). In regression models, we see how this indicator variable, called “Chinese virus,” is associated with changes in Democratic-leaning attitudes controlling for gender, income, education, age, place of birth, religious affiliation, and ideology, specifications similar to that of Kuo, Malhotra, and Mo (Reference Kuo, Malhotra and Mo2017). All control variables are scaled between 0–1.Footnote 22

In our pooled analyses of cross-sectional surveys, we include weekly fixed effects in our models. The subjects participating in each wave of the Nationscape data are different individuals; therefore, it is not plausible to apply an identical estimation model to each wave. Including weekly fixed effects reduces the subjects’ variation between the waves because it allows the intercept to have a different value in each wave. Specifically, the “Chinese virus” variable’s coefficient indicates the extent to which the variation in our dependent variables are associated with the main independent variable, controlling for differences in weeks. Our model specification is thus:

$$ \begin{array}{c}\hskip-3.5em {Y}_{i,t} = {\beta}_0+{\beta}_1\mathrm{Trump}\ \mathrm{Statement}\;\mathrm{on}\;{\mathrm{Chinese}\ \mathrm{Virus}}_t\\ {}\hskip-1.9em + {\beta}_2{\mathrm{Female}}_i+{\beta}_3{\mathrm{Income}}_i+{\beta}_4{\mathrm{Education}}_i\\ {} + {\beta}_5{\mathrm{Age}}_i+{\beta}_6\mathrm{Place}\;{\mathrm{of}\ \mathrm{Birth}}_i+{\beta}_7{\mathrm{Protestant}}_i\\ {}\hskip-12em + {\beta}_8{\mathrm{Liberal}}_i+{\sigma}_t{\mathrm{Week}}_t+\varepsilon \end{array} $$

$$ \begin{array}{c}\hskip-3.5em {Y}_{i,t} = {\beta}_0+{\beta}_1\mathrm{Trump}\ \mathrm{Statement}\;\mathrm{on}\;{\mathrm{Chinese}\ \mathrm{Virus}}_t\\ {}\hskip-1.9em + {\beta}_2{\mathrm{Female}}_i+{\beta}_3{\mathrm{Income}}_i+{\beta}_4{\mathrm{Education}}_i\\ {} + {\beta}_5{\mathrm{Age}}_i+{\beta}_6\mathrm{Place}\;{\mathrm{of}\ \mathrm{Birth}}_i+{\beta}_7{\mathrm{Protestant}}_i\\ {}\hskip-12em + {\beta}_8{\mathrm{Liberal}}_i+{\sigma}_t{\mathrm{Week}}_t+\varepsilon \end{array} $$

Here i indicates an individual participant, and t indicates a different wave; i ranges from 1 to 6,730 and t ranges from 1 to 42.

We test the relationship between our main independent variable on four dependent variables. The first outcome variable is partisan identification: Democrat (1); Republican, Independent, or Something Else (0). We also assessed respondents’ favorability of the Democratic Party and their favorability toward the Democratic Party’s nominee Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election. The favorability variables range from Very favorable, Somewhat favorable, Somewhat unfavorable, or Very unfavorable, and are recoded between 0 and 1, with the highest value indicating the most favorability. We also created a Democratic Party Index as a fourth dependent variable, which gives us a broad overview of partisan leanings using the three aforementioned questions. The scale sums the three measures together and divides them by three to range from 0 to 1. Given the binary nature of the partisan identification variable, we ran logit regressions. For all other dependent variables, we ran OLS regressions.

Results

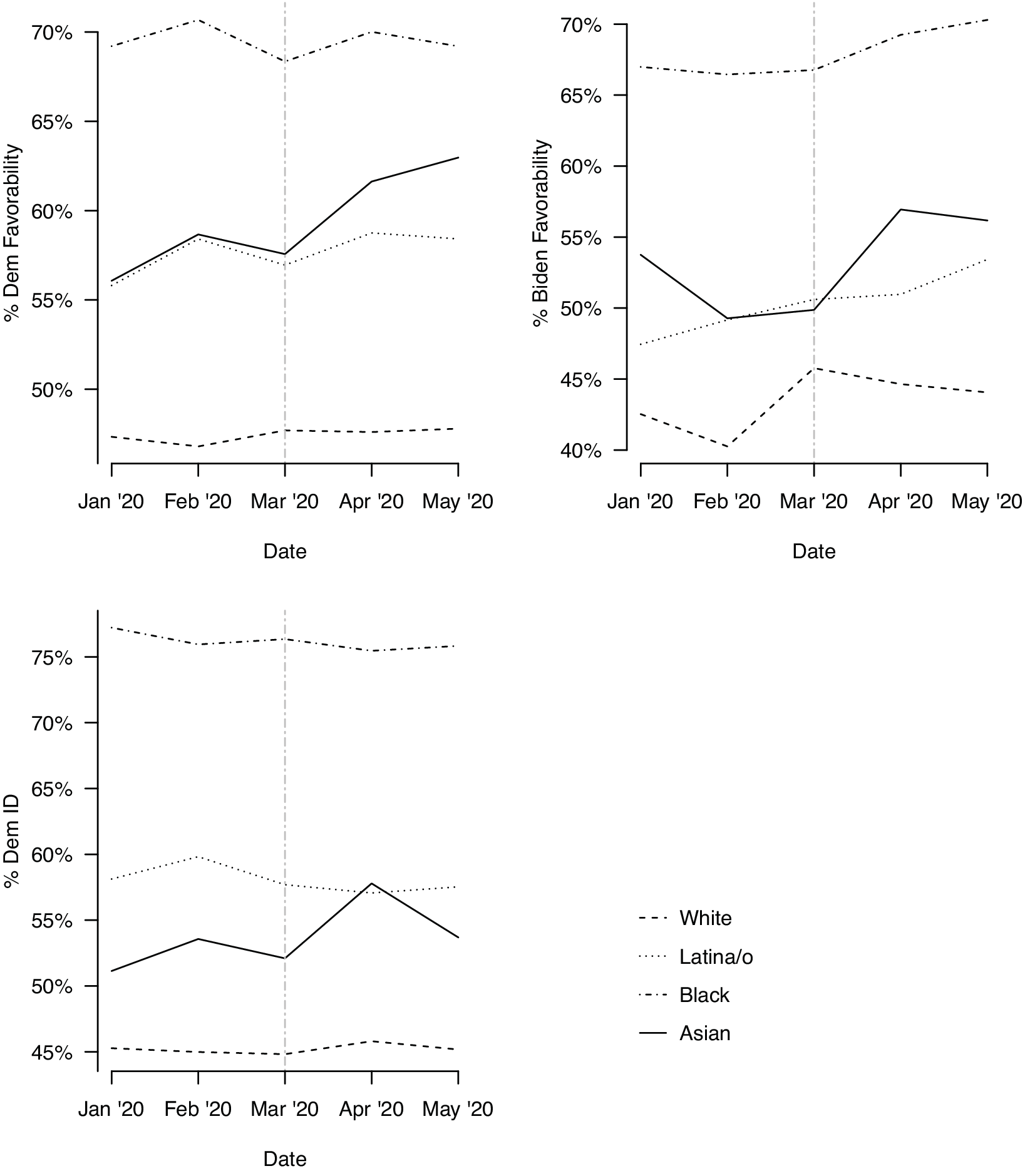

Descriptive analysis. Figure 4 displays how each racial group has changed in terms of Democratic-related attitudes on three measures. The bottom left panel in figure 4 shows that from right before Trump framed the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus” to after, Asian American identification with the Democratic Party increased by 6 points. There was some immediate drop off. However, about a month later, there was still a two-point increase compared to right before this framing. The group’s favorability of the Democratic Party also increased from 57.6% to 61.6%. Asian Americans’ favorability toward Joe Biden substantially picked up by seven points as well. This is while Whites, Latina/os, and African Americans experienced much less of a change in these attitudes over time comparing pre-and post-Chinese virus statements. These estimates are especially important in light of the history of Asian American non-partisanship, where many consider themselves to be non-partisan, moderate, or Independent.Footnote 23 The sustained change in party identification (2 points) is substantive due to how Asian Americans typically eschew party labels (Wong et al. Reference Wong, Ramakrishnan, Lee and Junn2011) and that Asian Americans are a rapidly growing proportion of the U.S. electorate (Budiman Reference Budiman2020).

Figure 4 Democratic Party attitudes over time by racial/ethnic group

Regression analysis. Next, we move to regression models, which will help account for some noise in the repeated cross-sectional data. In doing so, we pool together all the data made available to us between July 2019–May 2020 and analyze separately by each racial group. As mentioned, our main independent variable of interest is an indicator for pre- or post-Chinese virus framing. In our models, we control for income, education, age, gender, place of birth, religious affiliation, and ideology. We also account for weekly fixed effects. For simplicity, we reported the change in predicted probabilities in leaning toward the Democratic Party comparing those measured post-Chinese virus to those surveyed pre-Chinese virus, controlling for confounders. Full output from regression models is available in online appendix B.

Figure 5 displays the change in predicted probability of Asian Americans’ partisan attitudes comparing post-Chinese virus versus pre-Chinese virus, accounting for control variables and weekly fixed effects. The results suggest that Asian Americans’ partisan attitudes lean more Democratic after Trump framed COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus.” Democratic Party favorability increased by approximately six points; feelings toward the presumptive presidential nominee for the Democratic Party at the time also improved by an estimated 5 percentage points. Our results also show that Asian Americans’ identification with the Democratic Party increased by about five percentage points after Trump’s rhetoric (although p=0.156).

Figure 5 Change in Democratic-leaning attitudes after Trump’s statement on the “Chinese virus” (Asian Americans only)

In testing our expectations further, in Hypothesis 2B, we want to test if this trend toward leaning more towards the Democratic party is unique to Asian Americans relative to other racial/ethnic groups. In doing so, we examine the extent to which Latina/os, African Americans, and Whites have changed as well. Figure 6 displays the result of this comparison, which also shows the predicted change in probability of partisan attitudes comparing post- and pre-Chinese virus framing, controlling for other covariates in our models and accounting for weekly fixed effects (refer to online appendix B). Blacks also picked up in their favorability of Joe Biden but by an estimated percentage point lower than Asian American respondents. Before and after March 2020, Latina/o identification with the Democratic Party dropped. Biden favorability also dropped a bit after March 2020 among Whites. All other partisan attitudes have remained fairly unmoved before and after Trump framed COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus” for Latina/os, African Americans, and Whites.

Figure 6 Change in Democratic-leaning attitudes after Trump’s statement on the “Chinese virus” across race/ethnicity

For robustness, we estimated interaction models to better determine whether our “Chinese virus” variable indeed relates to Democratic partisan attitudes more substantively for Asian Americans compared to Latina/os, Blacks, and Whites. Table 1 displays the results from our interaction models for the Democratic Party Index dependent variable. Full output from these regressions with all controls and fixed effects are available in online appendix B. We find that relative to Latina/os, Blacks, and Whites, Asian Americans are more likely to have significantly shifted toward holding more favorable attitudes toward the Democratic Party after Trump began framing COVID-19 as the Chinese virus by about two points more compared to all other non-Asian racial/ethnic groups.

Table 1 Chinese virus and Democratic Party Index for Asian Americans relative to other racial/ethnic Groups

Note: OLS regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.01.

The results from our analyses across racial/ethnic groups speaks to the uniqueness and consistency of how elite-driven social exclusion relates to more Democratic-leaning public opinion, specifically for Asian Americans. Trump’s framing of the virus in racialized terms is disproportionately associated with leaning more Democratic for Asian Americans.

Discussion and Conclusion

The exclusionary environment during COVID-19, fueled by elite sources, has led Asian Americans to increase favorability with the Democratic Party. We demonstrate this with two studies. Study 1, based on an analysis of 1.4 million tweets over time, shows that Trump’s usage of the term “Chinese virus” led to increased usage of “Chinese virus,” “Kung flu,” and other racialized terms in the masses. We also find that anti-Asian sentiment has risen since the outbreak of COVID-19 in the United States. This more explicit racialized association between the pandemic and Asian Americans led by Trump and other GOP elites evokes, reinforces, and justifies hate against Asian Americans. Study 2 leverages pooled data from weekly cross-sectional surveys. We demonstrate that Asian Americans have leaned more toward the Democratic Party on various partisan measures after Trump’s usage of the Chinese virus. By comparison, the partisan attitudes of Whites, Latina/os, and African Americans do not change as much or as consistently during the same time period. Taken together, we find support for our hypotheses that elite messaging regarding the coronavirus has contributed and amplified social exclusion for Asian Americans and is turning this group uniquely away from the Republican Party.Footnote 24

Due to the diversity of the Asian American community, we also conducted disaggregated analysis by national origin. Our results suggest that this change in partisanship is strongest for Chinese Americans; non-Chinese groups such as Indian and Korean Americans also trend more towards the Democratic Party, but the difference is not statistically significant on conventional standards. Traditionally Republican-leaning groups such as Filipina/o and Vietnamese Americans were less likely to be swayed towards the Democratic Party than Chinese Americans. Given the historical differences in baseline partisan attitudes within the Asian American community before the pandemic (Lien Reference Lien1994; Lien, Conway, and Wong Reference Lien, Conway and Wong2003; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Ramakrishnan, Lee and Junn2011), as well as a loss in power with disaggregated sample sizes, we cannot make strong conclusions regarding national-origin differences (refer to online appendix B).Footnote 25

Our project adds to existing work on elite messaging and social exclusion (Kuo, Malhotra, and Mo Reference Kuo, Malhotra and Mo2017) by demonstrating how elite-driven rhetoric contributes to the activation of latent anti-Asian bias, leading to normalization of social exclusion at the mass public level. We also find evidence of the “Trump effect” (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Merolla, Shah, Lemi, Collingwood and Ramakrishnan2019) wherein Trump’s prejudiced speech activates and removes constraints upon already biased individuals, leading them to be more willing to express their prejudice. We also add to the literature on elite driven theories of public opinion, race, and ethnic politics, and marginalized groups’ politics during times of pandemic (see Adida, Dionne, and Platas Reference Adida, Dionne and Platas2020; Cohen Reference Cohen1999; Darling-Hammond et al. Reference Darling-Hammond, Michaels, Allen, Chae, Thomas, Nguyen, Mujahid and Johnson2020; Dionne and Turkmen Reference Dionne and Turkmen2020; Gadarian, Goodman, and Pepinsky Reference Gadarian, Goodman and Pepinsky2021; Hoppe Reference Hoppe2018; Nelkin and Sander Reference Nelkin and Sander2020; Reny and Barreto Reference Reny and Barreto2020).

We recognize the limitations of this project and offer avenues for future work. Due to accessibility, we only utilized data made available to us through May 2020, which cannot capture whether or not (or how) respondents actually voted in the 2020 presidential election.Footnote 26 Also, given the difficulty in sampling Asian American voters such as language barriers and incidence rates, as well as wide variance in exit poll estimates,Footnote 27 we are cautious about not making claims about how this factored into the actual breakdown of the 2020 presidential election. Future work may leverage precinct-level election returns released by county registrars (Sadhwani Reference Sadhwani2020, Reference Sadhwani2021; Lee, Chan, and Masuoka Reference Lee, Chan and Masuoka2021; Leung Reference Leung2021) to estimate the partisan preferences of Asian Americans at the local and state levels. Some preliminary studies on vote performance that leverage Asian Americans’ voter database files do estimate that approximately 67% of Asian American voters voted for Biden (Ghitza and Robinson Reference Ghitza and Robinson2021). Their analysis further suggests that claims about Trump doing better among Asian American voters in 2020 compared to 2016 are likely overstated. Ghitza and Robinson (Reference Ghitza and Robinson2021) find that Trump only did 1% better among Asian Americans across the two election cycles. Their estimates of vote shifting among other minority groups, such as Blacks and Latina/os, find that they did lean heavier towards Trump in 2020, relative to Asian Americans (+3% and +8%, respectively). We align with their argument, in addition, that because Asian Americans grew in their share of the electorate and the group’s turnout increased 39% from 2016 (62% overall turnout in 2020), this largely “benefitted Democrats.”

The murders of Daoyou Feng, Delaina Ashley Yaun Gonzalez, Hyun Jung Grant, Suncha Kim, Paul Andre Michels, Soon Chung Park, Xiaojie Tan, and Yong Ae Yue in Atlanta, Georgia,Footnote 28 the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes (Jeung and Nham Reference Jeung and Nham2020), and the continued usage of the term “China virus” by former President Trump suggests that anti-Asian bias continues to perpetuate.Footnote 29 The results of our project here have implications for future presidential elections as partisan attitudes are key indicators of propensity to vote. Asian Americans are the fastest-growing racial group in the United States (Budiman and Ruiz Reference Budiman and Ruiz2021). As a growing community with an increasing number of eligible voters, Asian Americans are poised to take a more important position in the U.S. electorate, especially in swing states such as Nevada, Virginia, and Georgia. This is not just in federal elections but in state and local politics as well. The rapid population growth and continued social exclusion at the hands of elites and the public necessitates a greater study of this group moving forward.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592721003091.

Appendix A. Twitter Data

Appendix B. Survey Data

The authors are grateful for feedback and comments from discussants and participants of the 2020 American Political Science Association Annual Meeting, where a previous version of this paper was presented. We also thank Charles Crabtree and Michael Tesler for their generous support through various stages of this manuscript.