Outsized media attention is a key feature in all political scandals, which require a “communicative event” in their early stages by definition (Shaw Reference Shaw1999). Media attention leads to more media attention: stories in the headlines continue to dominate coverage, resulting in news “feeding frenzies” (Sabato 1994). The news media tend to feature negative and personalized stories that are expected to increase attention from consumers (Rosenstiel et al. Reference Rosenstiel, Just, Belt, Pertilla, Dean and Chinni2007), resulting in high levels of sustained media attention for political scandals (Galvis, Snyder, and Song Reference Galvis, Snyder and Song2016; Patterson Reference Patterson1993).

Despite the media’s central role in political scandals, the prevailing scholarly wisdom predicts that scandal coverage will have minimal effects on public evaluations of the leaders involved (Bennett and Iyengar Reference Bennett and Iyengar.2008). Partisans loyally support their party’s leaders and often seem impervious to news that portrays those leaders in a negative light (Bartels Reference Bartels2002). The proliferation of media channels may also weaken the impact of scandals: given many choices, most consumers will not choose political news, are less likely to be influenced by political news, and can choose their news based on their partisan predispositions (Arceneaux and Johnson Reference Arceneaux and Johnson2013; Prior Reference Prior2007; Stroud Reference Stroud2011).

But what happens when news about a political scandal is inescapable? Coverage of the Bill Clinton-Monica Lewinsky scandal in 1998, for example, influenced public opinion initially, when the tone of coverage was consistently negative (Zaller Reference Zaller1998). Without randomly varying news exposure, however, it is difficult to know how much media coverage affected the public’s attitudes towards President Bill Clinton. While an experimental approach could address this causal inference problem, most experimental studies on the effects of political scandals rely upon a single exposure to a treatment (Berinsky et al. Reference Berinsky, Hutchings, Mendelberg, Shaker and Valentino2011; Maier Reference Maier2011; Doherty, Dowling, and Miller Reference Doherty, Dowling and Miller2011), lowering the generalizability of the findings and failing to capture effects of sustained media attention.

We address these concerns using a unique, repeated-exposure experimental design that either randomly supplied participants with news about the scandal concerning President Donald Trump’s alleged collusion with Russian interests during the 2016 campaign, or removed most of those stories from view, over the course of one week. This approach mimics sustained media attention to a political scandal and disentangles the effects of media coverage from selection in the context of a high-choice media environment.

Our results show that intense media attention to a political scandal may change partisans’ evaluations of a president representing their party, overcoming the influence of partisanship and selective exposure. We find that Republicans randomly assigned to see additional Trump-Russia headlines reacted more negatively than did Democrats or Independents, rating Trump’s performance lower and expressing more negative emotions towards him. Democrats rated Trump lower as well, but the effect was smaller, while Independents rated Trump somewhat higher when exposed to more Russia coverage. Republicans’ attitudes towards the media were unchanged and clicking on the articles did not moderate the effects. We argue that these results are good for democracy and political accountability: partisan loyalty may not be so blind (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2016).

Presidential Scandals and Public Opinion

The president is inherently newsworthy: characterized by power held by one individual, the office satisfies journalistic standards of social significance, celebrity, conflict, and drama, guaranteeing regular and substantial news coverage for the president regardless of their performance in office (Gans Reference Gans1979). Citizens hold presidents uniquely responsible for the nation’s well-being and reward or punish the president according to their perceptions of national conditions, both at the ballot box and in day-to-day approval surveys (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2016; Erikson and Wlezien Reference Erikson and Wlezien.2012; Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981; Mueller Reference Mueller1970, Reference Mueller1973; Nicholson, Segura, and Woods Reference Nicholson, Segura and Woods2002; Sides and Vavreck Reference Sides and Vavreck2013; Tufte Reference Tufte1975). The news media provide direct information about national conditions and the president’s role in producing those conditions, and news agendas can shape evaluations of the president by changing the criteria that citizens use to make judgments (Althaus and Kim 2006; Edwards, Mitchell, and Welch Reference Edwards, Mitchell and Welch1995; Gronke and Newman Reference Gronke and Newman2003; Hetherington Reference Hetherington1996; Iyengar and Kinder Reference Iyengar and Kinder1987; Krosnick and Kinder Reference Krosnick and Kinder.1990; Miller and Krosnick Reference Miller and Krosnick2000).

Scandal news threatens the public standing of implicated officials, reducing their vote share when scandal coverage is elevated (Hamel and Miller Reference Hamel and Miller.2019). Beyond merely reporting on scandals, news media shape public reactions through the frames they employ. For example, the news may cover embroiled leaders’ efforts to portray the scandal as a partisan vendetta by their opponents, which can dampen negative effects on public opinion (Shah, Watts, Domke, and Fan, Reference Shah, Watts, Domke and Fan2002). Other contextual factors such as competition, race, and timing moderate the effects of scandal news. Scandal-plagued politicians attract better challengers (Basinger Reference Basinger2012), and incumbents facing scandals may choose to strategically retire rather than face electoral defeat (Banducci and Karp Reference Banducci and Karp1994). Incumbents are punished more for corruption charges than challengers, and black candidates may suffer greater consequences from sex scandals than white candidates (Berinsky et al. Reference Berinsky, Hutchings, Mendelberg, Shaker and Valentino2011; Welch and Hibbing Reference Welch and Hibbing1997). Scandal news early in a campaign may impact voters’ assessments more than later scandal news, and repetitive scandal news only changes opinions when new information is given (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2014).

Personal and professional scandals have different consequences on public opinion (Funk Reference Funk1996; Miller Reference Miller1999; Zaller Reference Zaller1998). Bribery, obstruction of justice, or criminal acts against political opponents are directly related to job performance, whereas sex scandals may only implicate assessments of a politician’s personal character without broader implications for their political approval. For example, financial scandals lower both political and personal evaluations of politicians, whereas sex scandals lower only personal evaluations (Doherty, Dowling, and Miller Reference Doherty, Dowling and Miller2011). Cover-ups involving abuse of power magnify these negative effects, while perceptions of professional competence help politicians survive scandal, at least among knowledgeable citizens (Funk Reference Funk1996). Reactions may also differ based on the domain of evaluation: for example, Bill Clinton’s approval rose during his impeachment scandal, but Americans across party lines lowered their evaluations of his morality and compassion (Miller Reference Miller1999).

Partisans process scandal news and update their judgments about political leaders differently depending on the party of the leader involved (Eggers Reference Eggers2014; Miller Reference Miller1999; Zaller Reference Zaller1998). Citizens need the motivation and capacity to process new information, making biases strongest among the most partisan and most knowledgeable (Kunda Reference Kunda1990). Partisans often seek out agreeable sources of information; avoid those expected to be disagreeable; uncritically accept information that reinforces their preexisting views; and discredit challenging information through counter-arguing (Bartels Reference Bartels2002; Lodge and Taber Reference Lodge and Taber2013). It is difficult to predict the behavior of independents in the context of scandals: those who do not affiliate with a party may vote like partisans at times, but define themselves by their non-partisan identity, not their opposition to a specific person, party, or ideology.Footnote 1

These dynamics make predicting partisan response to scandals a complex task. In the context of scandals, some partisans in the party of the politician in question resist negative information about their party and its leaders (Slomcyznski and Shabad Reference Slomczynski and Shabad2011; Vivyan, Wagner, and Tarlov Reference Vivyan, Wagner and Tarlov2012), while others update some of their beliefs when confronted with credible information (Guess and Coppock 2016; Klar and Krupnikov Reference Klar and Krupnikov2016; Nyhan et al. Reference Nyhan, Porter, Reifler and Wood2017; Zaller and Feldman Reference Zaller and Feldman1992). During the period studied, Republicans routinely expressed more ambivalence about Donald Trump than did Democrats. In June 2017, the same month our study was in the field, 71% of Republicans strongly approved of Trump while 82% of Democrats strongly disapproved, showing that Republicans’ overall evaluations of Trump were more malleable (Pew Research Center 2017).Footnote 2 While partisan attitudes are generally resistant to change, we expect that Republicans’ relatively ambivalent views of Trump should become more negative in response to accessible considerations about a scandal (Bassili Reference Bassili1996; Lavine Reference Lavine2001; Miller and Peterson Reference Miller and Peterson2004; Zaller and Feldman Reference Zaller and Feldman1992). People’s willingness and ability to resist counter-attitudinal information is limited in the face of repeated exposure to it, as in the case of heavy scandal coverage, despite the power of motivated reasoning to shape responses to political information (Kunda Reference Kunda1990; Redlawsk and Lau Reference Redlawsk and Lau2006; Taber and Lodge Reference Taber and Lodge.2006). We therefore expect to observe stronger effects of scandal news among Trump’s fellow Republicans—some of whom will be motivated to resist negative news more than others—than among Democrats.

The Trump-Russia scandal produced large amounts of negative news coverage for the Republican president and was a prominent story while our study was in the field. The scandal, detailed later, is both personal and professional in nature, due to the media’s portrayal of the connections between Trump’s businesses, his children, and his presidential campaign. As such, we should expect to find effects of scandal news across several areas of evaluations of Trump. While Democrats might be most receptive to negative news about Trump, we expect the strength of their original opinions of Trump to be far greater than that of Republicans, many of whom have been ambivalent about him from the start. We therefore expect greater exposure to Trump-Russia news to depress Trump’s evaluations among Republicans by more than Democrats.

Hypothesis: Greater exposure to scandal-related stories will lead to more negative presidential performance ratings and negative emotions related to the president for people in the president’s party, but not for opposing partisans.

The Trump-Russia Scandal

President Trump faced constant media coverage of several scandals in the first year of his presidency. Our focus is on coverage of the Russia scandal: the investigation into whether Trump’s campaign colluded with Russian intelligence in the 2016 campaign, and whether Trump obstructed justice in the pressuring and subsequent firing of FBI Director James Comey. Given the many continuing developments in this story, this section provides a brief overview of the state of the Trump-Russia investigation as of June 2017, when our study was in the field.

Reports of contact between the Trump campaign and Russian officials surfaced before the 2016 election, and coverage of Trump’s connections with Russia intensified after his victory. On November 18, retired General Michael Flynn was announced as National Security Advisor in the incoming Trump administration, despite widely publicized evidence of his contacts with Russian officials (Berkowitz, Lu, and Vitkovskaya Reference Berkowitz, Lu and Vitkovskaya2017). In March, the president reportedly asked several government officials, including FBI Director James Comey, for a reprieve for Flynn (Berkowitz, Lu, and Vitkovskaya Reference Berkowitz, Lu and Vitkovskaya2017). Attorney General Jeff Sessions failed to report in-person contact with the Russian ambassador during his confirmation hearing before Congress, and subsequently recused himself from involvement in any Russia-related investigations (BBC News 2017). On May 9, President Trump fired Comey. Several days later, the Department of Justice appointed former FBI Director Robert Mueller as a special counsel to investigate Russia’s possible collusion with the Trump campaign ahead of the 2016 presidential election, intensifying media coverage once more (BBC News 2017).

Leading up to our news portal experiment, several high-profile developments unfolded in the scandal. On June 8, Comey testified before the Senate committee, revealing details of his earlier exchanges with Trump over the Flynn probe. While our study was in the field, on June 13, Attorney General Jeff Sessions spoke before the Senate Intelligence Committee in response to the Comey testimony, once again denying having any communications with Russians (Balluck Reference Balluck2017).

Data: The Portal Panel

It is difficult to accurately measure media consumption in observational studies, and even more challenging to determine exposure to specific outlets, stories, or topics (Prior Reference Prior2009). Our experimental design addresses these concerns by enrolling people in a Google News-style online portal for one week. Those randomly assigned to the treatment group received high levels of Trump-Russia scandal coverage, while the control group saw little to none. The absence of scandal news coverage in a participant’s news portal may lower both the accessibility and perceived importance of the scandal (Iyengar and Kinder Reference Iyengar and Kinder1987; Metzger Reference Metzger2000; Miller and Krosnick Reference Miller and Krosnick2000).

The Trump-Russia treatment was part of a fully factorial design that also included four other binary factors, included as control variables in the analyses that follow: additional fact-checking stories, more stories featuring intra-party disagreement, relative emphasis on immigration compared to health care, and stories defending the importance of journalism. Assignment to these conditions is accounted for by including them as covariates in the ensuing analyses, with full results including these variables in the regression tables in the online appendix.Footnote 3

Stories about the Trump-Russia scandal were identified using a set of keywords: “Russia,” “Comey,” “Flynn,” “Mueller,” and “Sessions.” In total, sixty-eight stories on the Trump-Russia scandal were included in the treatment group over the course of the week. Authors manually reviewed the results of the keyword queries to ensure these stories were valid and to remove false positives. By randomly assigning coverage in an online context, we can assess attitudes before and after exposure to scandal news, enabling us to make causal inferences.

A panel of participants was paid to use this portal as their primary news source for a week.Footnote 4 Participants were asked their partisanship (coded as Democrat, Republican, or Independent), as well as other demographic variables, before gaining access to the portal.Footnote 5 The news portal presented participants with a chronological feed of constantly updating top stories.Footnote 6 An example of the news portal user interface is given in figure 1.

Figure 1 A partial example of the news portal feed utilized in this experiment

Participants were recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service. Only those workers with their location set to the United States were allowed to see the task on Mechanical Turk, which minimizes the possibility that workers from other countries misrepresented their location for the purposes of being included. There were 1,830 participants in the pre-test and 1,187 who completed the post-test. The portal opened at 5:00 a.m. CT on Monday, June 12, 2017, and closed at 10:00 a.m. CT on Friday, June 16, 2017. The average portal user saw 328 stories over the course of the week and clicked on 19 to read in greater detail. The post-test survey was administered after the portal closed to those whose portal usage throughout the week exceeded a certain threshold.Footnote 7 Participants were paid $1 for completing the pre-test and post-test survey, and up to an additional $3 based on how much they used the portal. These incentives were designed to produce a sample of regular online news users. As explained to prospective participants and in reminder messages to participants, bonuses for portal usage were not intended as compensation for spending more time reading news than they otherwise would. Instead, they were intended as compensation for using our news portal instead of other news sources.

Methods

Our study has the advantage of random assignment, but our news portal setup means that delivery of the treatment is less controlled than is typical and can be thought of as quasi-experimental. In this way, our data lends itself to panel analyses, estimating the effects of a news event between survey waves. As there are likely unobservable real-world influences at work, panel regression methods which account for unobserved heterogeneity between individuals and time periods are appropriate. To this end, we use random-effects panel regressionFootnote 8 similar to other experiments and studies about political learning from the news media (Allison Reference Allison2009; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2013, table 1; Dilliplane Reference Dilliplane2014, table 4).

Since the portal experiment contained other conditions for concurrent studies, we include those treatment conditions as control variables. Given the expected moderating effects of partisan identification, we interact partisanship with inclusion in the Trump-Russia condition. The full specification is described in Equation 1:

In Equation 1, μ is an intercept, Russia indicates assignment of the respondent to the Trump-Russia stories condition, Repub indicates self-identification as a Republican (coded as 0 or 1), Russia X Repub indicates the interaction term (i.e., self-identified Republicans randomly assigned to receive more Trump-Russia stories), Dem indicates self-identification as a Democrat (coded as 0 or 1), Russia X Dem indicates another interaction term (i.e., self-identified Democrats randomly assigned to receive more Trump-Russia stories), ![]() $<italic>{\rm{\Gamma }}</italic>$Conditions i represents a set of coefficients on the other conditions in the study (more immigration than health care stories, more intra-party disagreement, more fact-checking stories, and more defense of journalism stories), and

$<italic>{\rm{\Gamma }}</italic>$Conditions i represents a set of coefficients on the other conditions in the study (more immigration than health care stories, more intra-party disagreement, more fact-checking stories, and more defense of journalism stories), and ![]() $\Delta {\varepsilon _i}$ indicates the difference in random error terms assumed to be independent of covariates at all periods (Allison Reference Allison2009). Since we account for Republicans and Democrats in the Trump-Russia condition with interaction terms, this specification results in the main effect on the Trump-Russia variable capturing effects on Independents, the only remaining excluded group. This model therefore measures the within-individual variation in our dependent variables between the first and second time periods.

$\Delta {\varepsilon _i}$ indicates the difference in random error terms assumed to be independent of covariates at all periods (Allison Reference Allison2009). Since we account for Republicans and Democrats in the Trump-Russia condition with interaction terms, this specification results in the main effect on the Trump-Russia variable capturing effects on Independents, the only remaining excluded group. This model therefore measures the within-individual variation in our dependent variables between the first and second time periods.

We use several dependent variables to measure individual assessments of President Trump’s job performance, emotional attitudes towards Trump, attitudes towards the media, and usage of our news portal. These dependent variables assess whether Republicans and Democrats who were randomly assigned to view more Trump-Russia stories changed their assessments of Trump’s job performance or reacted emotionally to that news.Footnote 9

Presidential approval was assessed using two variables: a more traditional assessment of Trump’s handling of the job of president, and a second question assessing respondents’ views of the potential consequences of a Trump presidency. The job approval question followed the prompt, “Do you approve or disapprove of the way Donald Trump is handling his job as president?” Responses were coded from one (“Strongly disapprove”) to seven (“Strongly approve”). Responses from the initial wave of questions, pre-treatment, provide support for our expectation that Democrats were more certain about their attitudes towards Trump than Republicans: less than 8% of Republicans said they strongly approved, compared to 60% of Democrats who strongly disapproved. For the second question, respondents provided up to five perceived consequences of a Trump presidency, and then assessed those consequences on a five-point scale from “very bad” to “very good.” Both variables were rescaled from 0 to 1.

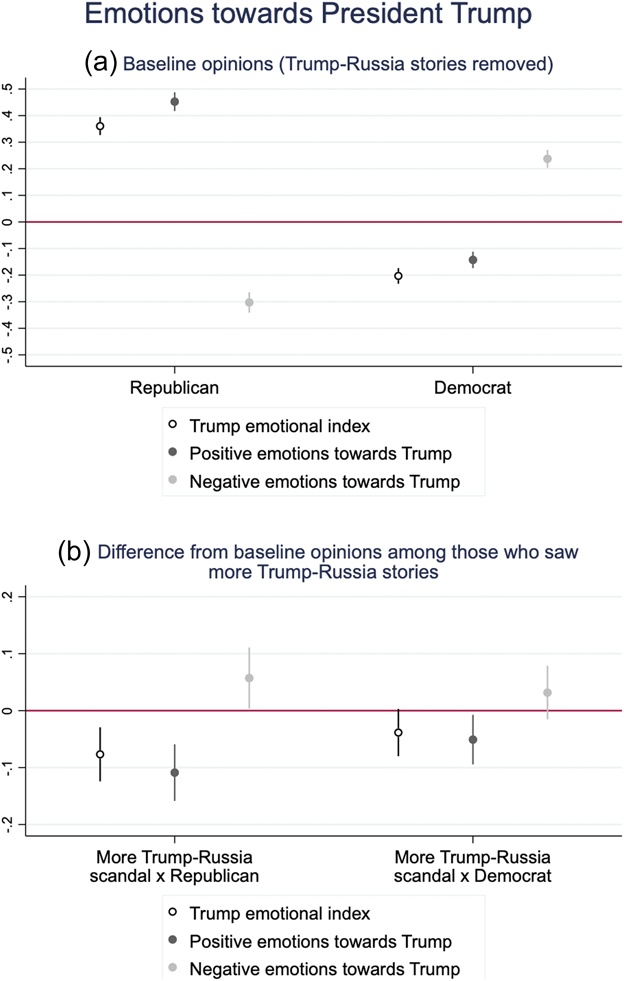

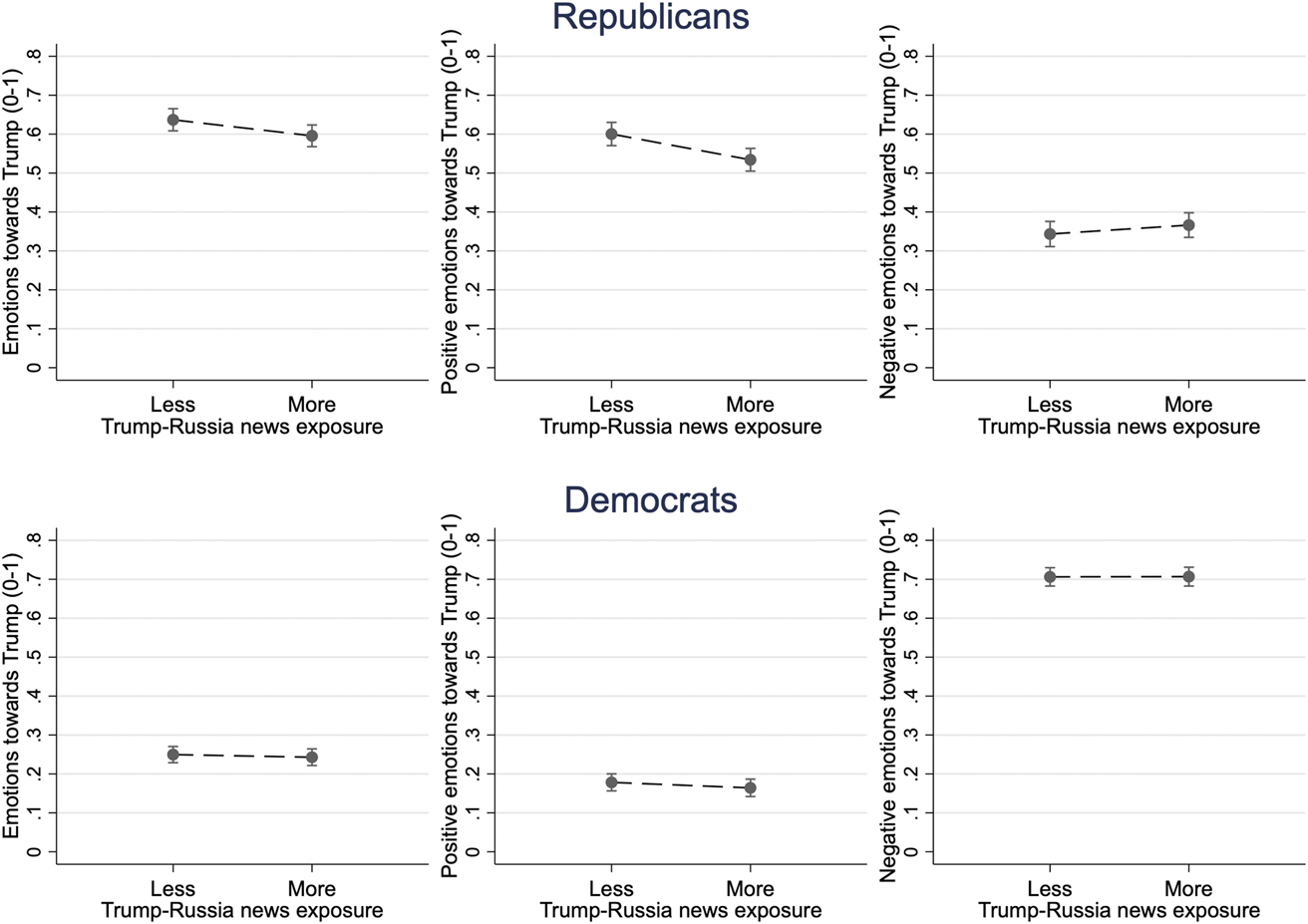

Respondents were also asked to assess their specific emotional reactions to President Trump according to eight given emotions: pride, enthusiasm, hopefulness, anger, anxiety, worry, outrage, and fear. Of these emotions, we categorize three as positive emotions (pride, enthusiasm, and hope), and the remaining five as negative emotions. Respondents rated their reactions on these emotions on a 1–7 scale, from “not at all” to “very much.” We created an emotional response index from these eight emotions variables to determine a range of emotional response. Negative emotions (anger, anxiety, worry, fear, outrage) were reverse coded so that all variable scales went from least positive to most positive; each variable was then rescaled from 1-7 to 0–6, all were added together, and the sum was divided by 48 to create a 0 to 1 emotional response index from most negative to most positive. In the analyses in figure 4 (table A2), Equation 1 was estimated using this index as a dependent variable, followed by analyses of the positive and negative emotions separately (rescaled from 0 to 1 as well).Footnote 10

Results: Trump Evaluations

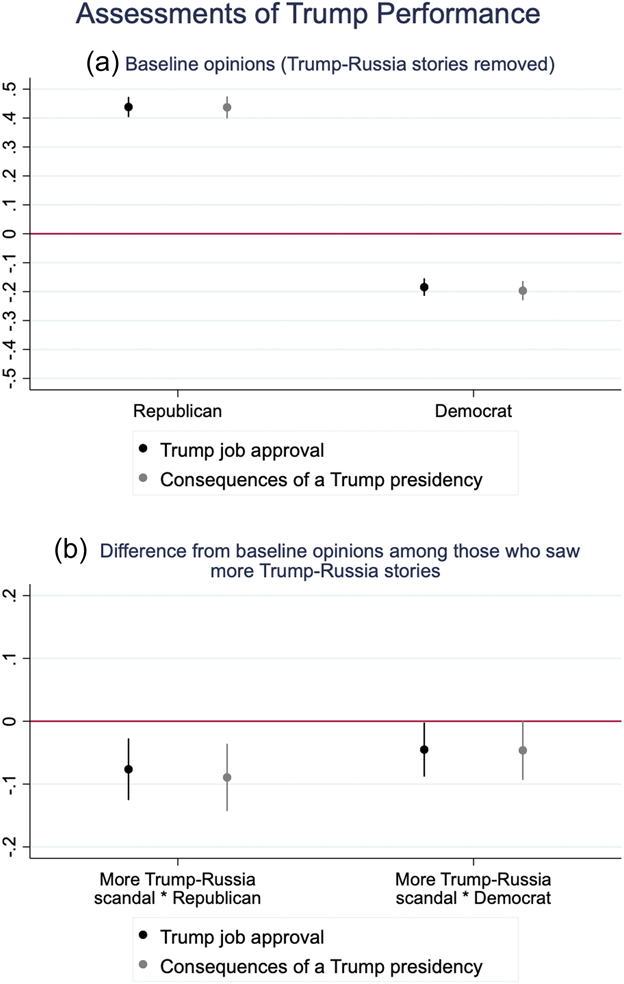

The following results, calculated using the random effects panel regression described in Equation 1, provide estimates of within-respondent opinion change that assess the effects of news coverage of the Trump-Russia scandal on the political attitudes of partisans over one week.Footnote 11 We present our results as plots of coefficients from our regression analyses and the marginal predicted probabilities of respondents’ opinions about President Trump (figures 2 and 4) and the media (figure 6), by partisanship and Trump-Russia news exposure. The coefficient plots contain two sections: the top panel (e.g., figure 2a) displays the baseline opinions of Republicans and Democrats in the condition where Trump-Russia scandal stories were removed. The bottom panel (e.g., figure 2b) displays the difference in opinions between partisans in the baseline group and the “treatment” group, which received additional news coverage of the Trump-Russia scandal during our week-long portal experiment. Full results from our regression analyses are included in the online appendix.

Figure 2 Coefficient plots of partisans’ ratings of President Trump by amount of Trump-Russia scandal stories in respondents’ news portal

Note: Points and lines denote coefficient point estimates and 95% confidence intervals. Full regression includes four other experimental conditions; full results are available in table A1 of the online appendix.

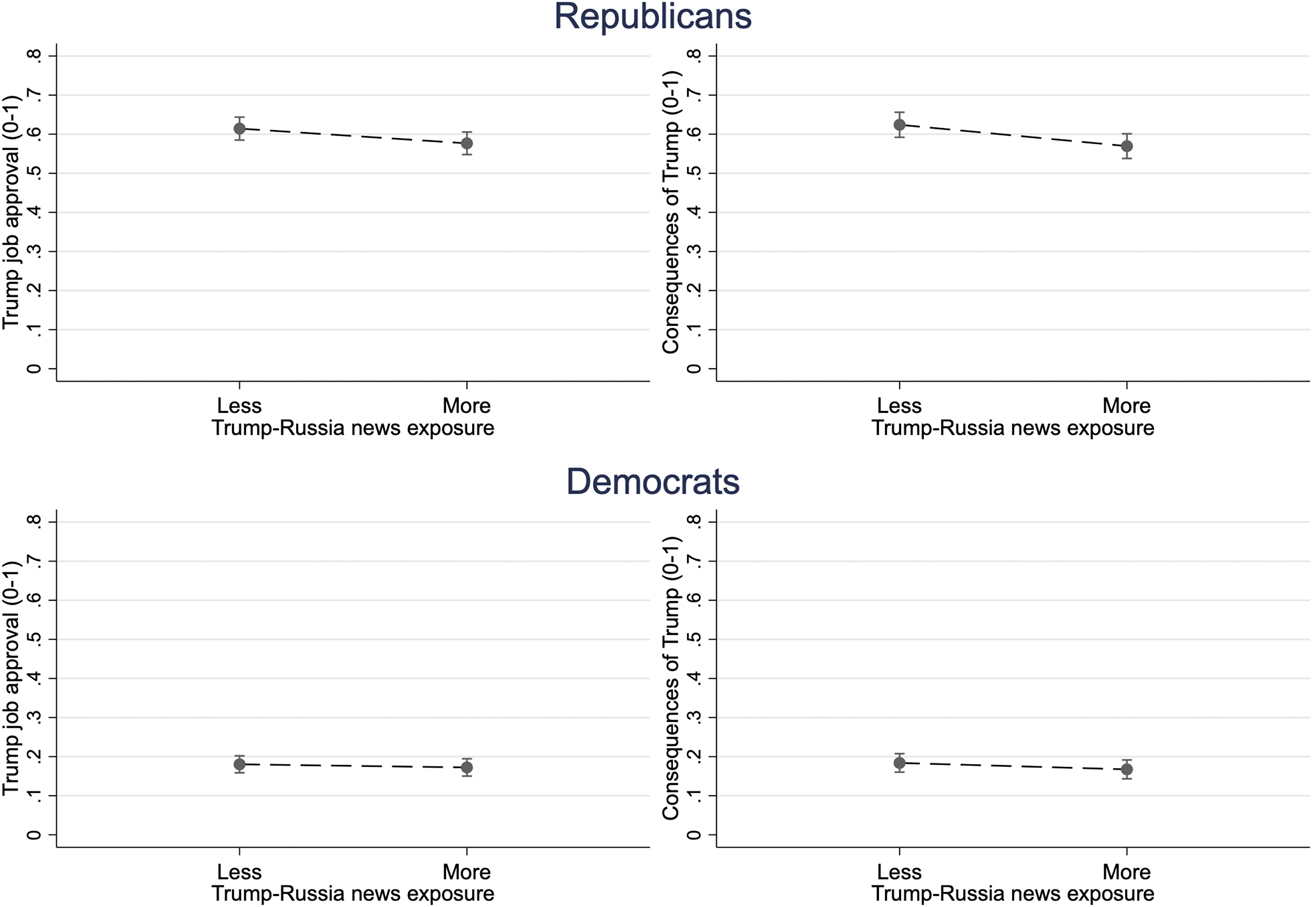

Figure 3 Marginal predicted probabilities of partisan ratings of President Trump’s job approval by the amount of Trump-Russia scandal stories in respondents’ news portal

Note: Calculated using “marginsplot” in Stata. Points and lines denote estimated marginal predicted probabilities and 95% confidence intervals of those estimates.

Figure 4 Coefficient plots of partisans’ overall emotions, positive emotions, and negative emotions towards President Trump by the amount of Trump-Russia scandal stories in respondents’ news portal

Note: Points and lines denote coefficient point estimates and 95% confidence intervals. Full regression includes four other experimental conditions; full results are available in table A2 of the online appendix.

Coefficient plots do not demonstrate the predicted levels of our various dependent variables, however, making it difficult to use them to interpret the substantive impact of our treatment. We use marginal predicted probabilities in figures 3 and 5 to demonstrate these substantive differences. These figures portray the differences in the predicted values of Trump assessments (figure 3) and emotional responses (figure 5) by partisanship and experimental exposure to news. These predicted probabilities account for exposure to other experimental conditions while restricting the analysis to within-respondent changes and are therefore most useful for understanding the substantive impact of randomized exposure to (or removal of) Trump-Russia scandal news.

Figure 5 Marginal predicted probabilities of partisans’ overall emotions, positive emotions, and negative emotions towards President Trump by the amount of Trump-Russia scandal stories in respondents’ news portal

Note: Calculated using “marginsplot” in Stata. Points and lines denote estimated marginal predicted probabilities and 95% confidence intervals of those estimates.

First, we examine whether exposure to presidential scandal news affects assessments of Trump’s present and future job performance. Unsurprisingly, Democrats and Republicans have very different opinions of President Trump’s performance for both dependent variables, job approval, and assessments of the consequences of Trump’s presidency. The coefficients on Republicans’ baseline opinions are significant and positive (b = 0.438, p < 0.01) and Democrats’ opinions are significantly negative (b = -0.184, p < 0.01), among those for whom Trump-Russia stories were removed (figure 2a).

How did opinions differ among those Republicans and Democrats who saw additional Trump-Russia stories? Exposure to more headlines about the Trump-Russia investigation is associated with a significant and negative effect on both measures of Trump approval among his fellow Republicans. Republicans in the Trump-Russia treatment condition (n = 142), who saw relatively more news on the scandal, rated his job performance 7.6% lower (p < 0.01) and expected the consequences of a Trump presidency to be 8.9% more negative (p < 0.01) than did Republicans for whom Trump-Russia news was removed. Republicans were not inclined to counter-argue or reinforce their partisan views: more exposure to scandal news about Trump negatively impacted evaluations of his job performance. Democrats who saw more Trump-Russia articles (n = 231) also decreased their evaluations of Trump, by around 4.5% in job approval (p < 0.05) and 4.6% assessing the consequences of Trump’s presidency (p < 0.1). Though Democrats rated Trump much lower overall, additional exposure to Trump scandals did not diminish their evaluations as much as it did for Republicans.Footnote 12

What are the substantive impacts of exposure to Trump-Russia news on Trump approval for Democrats and Republicans? Figure 3 presents plots of predicted marginal probabilities for each party, with dashed lines between those in the “less Trump-Russia news” condition and the “more Trump-Russia news” condition to visualize the effect of Trump-Russia news exposure.

The net decrease in evaluations of Trump between those who see less or more Trump-Russia coverage is larger for Republicans than for Democrats, though Republicans’ evaluations of the president remain substantially more favorable. Republicans who saw more Trump-Russia coverage were 4.5% less approving of Trump’s job performance, a statistically significant difference in marginal predicted probabilities (p = 0.038). Democrats were less approving overall, but the difference between those who saw less or more Trump-Russia coverage was not statistically significant (3%; p = 0.122). The differences were similar for assessments of the consequences of Trump’s presidency: Republicans were 6.1% less optimistic after seeing a week of Trump-Russia stories (p = 0.009), while Democrats were 4% less optimistic (p = 0.053). The differences between Republican respondents were statistically significant, and the differences between Democratic respondents—though substantialFootnote 13—were not significant at the p < 0.05 level, providing support for our hypothesis.

Results: Emotions toward Trump

Republican respondents rate Trump’s job performance more negatively when exposed to more Russia scandal news, but what about their emotional responses to the president? Figure 4 presents coefficients from tests of the impact of Trump-Russia news exposure across the indices of all emotions, positive emotions, and negative emotions.

The baseline attitudes in figure 4a show that, once again, Republicans have higher positive emotions and lower negative emotions towards Trump, while the opposite is true for Democrats. There is a significant and negative impact on emotional responses to Trump among Republicans who were exposed to more Trump-Russia coverage in their news portal. Republicans in the Trump-Russia condition experienced a 7.7% drop in overall emotional valence towards Trump, though the index of all emotions does not tell us specifically which emotional responses were impacted.Footnote 14 Democrats’ overall emotions towards Trump cooled by 3.8% (p < 0.1), again less than Republicans’ emotions changed. Similar to the approval measures in figures 2 and 3 above, the effect on Republicans was largest.

Were these changes in emotional attitudes the result of changes in positive emotions (pride, enthusiasm, hope), or negative emotions (anxiety, worry, outrage, anger, fear), or both? Once again, Republicans feel more positive emotions towards Trump, and Democrats more negative emotions, in the baseline condition (figure 4a). Figure 4b shows that viewing more Trump-Russia stories caused a significant negative effect (-10.9%; p < 0.01) on Republicans’ positive emotions towards Trump, while the negative effect on Democrats’ positive emotions is about half that size (-5.1%; p < 0.05). When the Trump-Russia story is in the news, it dampens Republicans’ positive feelings about President Trump, making them significantly less proud, hopeful, and enthusiastic. Republicans in the Trump-Russia condition also expressed 5.7 percent more negative emotions (p < 0.05), showing that the overall negative emotional effect is explained mainly, but not exclusively, by a dampening of positive feelings towards Trump. Democrats’ negative emotions towards Trump were not significantly affected. Reactions from partisans in the president’s opposing party seem to be less easily moved: their negative emotions towards Trump are at their peak and cannot increase significantly. These results also support our hypothesis: the president’s partisans respond more to scandal news, and their impressions of their president suffer when they encounter more scandal news.

What were the substantive impacts of these changes in emotions towards Trump? We display the marginal predicted probabilities of the analyses in figure 5, below, for Democrats and Republicans.

Republicans’ overall emotions towards Trump declined from 0.637 to 0.596 on the 0-1 index of our eight emotional variables when they saw more Trump-Russia stories, a significant decline in pairwise tests comparing the marginal predicted probabilities (p = 0.022), while the difference was not significant for Democrats across conditions (0.25 vs. 0.243; p = 0.114). As in figure 4, there was a much larger difference in positive emotions: Republicans in the Trump-Russia news condition scored 0.534 on the positive emotions index, compared to 0.6 when Trump-Russia stories were removed (p = 0.001), a decrease of 11%. Democrats’ positive emotions towards Trump also dropped significantly when they saw more Trump-Russia stories (0.178 vs 0.164; p = 0.022), a decrease of 7.9%. Respondents from both parties experienced a significant decrease in positive emotions upon seeing more Russia stories, though the impact on Republicans was larger once again. Though, for both parties, negative emotions towards Trump increased when they saw more Trump-Russia stories, neither difference was significant.

These substantive tests demonstrate that emotional responses to Trump are clearly negatively affected when partisans of either party see more stories about the Russia scandal, and most of the effect is explained by a decrease in positive emotions. Democrats are affected by exposure to Trump-Russia content, but their response is muted compared to that of Republicans.

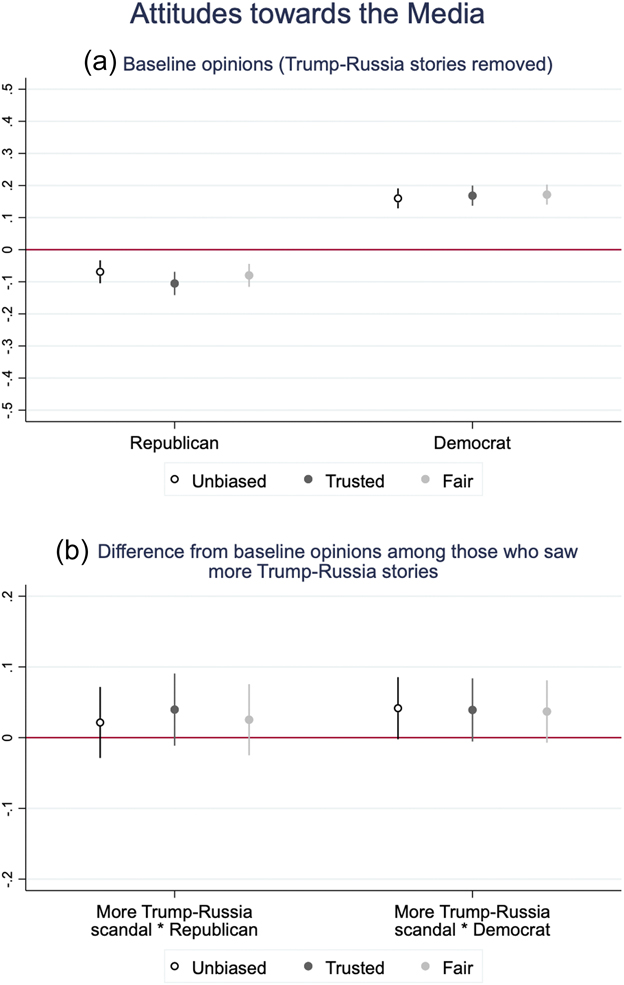

Results: Media Evaluations and Portal Use

Though these findings demonstrate that there are consequences of scandal news for the politician in question, it is unclear whether exposure to scandal news influences other political attitudes. Given the increasingly hostile attitudes of Republicans towards news media, for instance, we might expect exposure to presidential scandal news to influence Republican attitudes towards the media. The negative effects of a scandal may extend beyond the politician in question to other aspects of politics (Lee Reference Lee2018), and in the real world, the effects observed in tables 1 and 2 may be muted by selective exposure to like-minded media (Arceneaux and Johnson Reference Arceneaux and Johnson2013; Stroud Reference Stroud2011). Republican resistance to counter-attitudinal information may lead to negative evaluations of the news media, facilitated by historically low levels of media trust among Republicans and Trump supporters (Guess, Nyhan, and Reifler Reference Guess, Nyhan and Reifler2017). Since attitudes towards Trump and the media are correlated, we expect exposure to Trump-Russia scandal news will depress Republican attitudes towards the media even further.

Media attitudes were assessed through three questions asking whether respondents consider the mainstream media to be unbiased, trustworthy, and fair. These attitudes are assessed on a Likert scale, initially coded from one to seven (strongly disagree to strongly agree) and recoded as a 0–1 index. Using these variables, we assess whether increased exposure to the Trump-Russia scandal shifted media attitudes among Republicans, with results displayed as coefficient plots in figure 6.

Figure 6 Coefficient plots of partisans’ attitudes towards the media by the presence or absence of Trump-Russia scandal stories in respondents’ news portal

Note: Points and lines denote coefficient point estimates and 95% confidence intervals. Full regression includes four other experimental conditions; full results are available in table A3 of the online appendix.

Consistent with recent findings (Knight Foundation 2018), in the baseline condition, Republicans have a negative view of the media and Democrats a positive view (figure 6a). In figure 6b, among Republicans, there is no significant effect of viewing more Trump-Russia stories on media attitudes across trust, bias, or fairness. Republicans’ distrust of the media does not seem to influence their reaction to reading about the Trump-Russia scandal in their online news feed. There is a small increase in Democrats’ perceptions of media’s unbiasedness (4.2%; p < 0.1) and trust in media (3.9%; p < 0.1) when exposed to more Trump-Russia content.

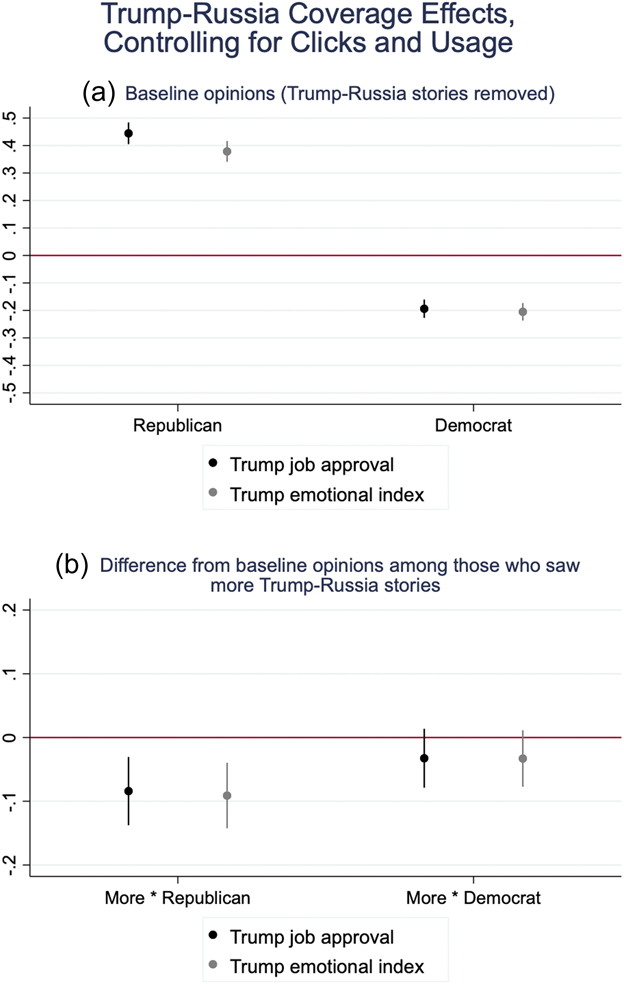

Finally, we examine whether clicking on the stories themselves may moderate the observed effects. The data shows that Republicans are less likely to read the Trump-Russia stories they encounter as headlines, and thus receive lower levels of exposure to the full content of scandal-related articles: Republicans read, on average, 5.8% of the Trump-Russia stories they encountered, compared to 8.3% of Democrats and 7.6% of Independents.Footnote 15 In the online news environment, however, exposure to a story may not require active engagement: a change in the balance of headlines may be sufficient to reshape opinions. In Figure 7, below, we present results of estimations of the earlier models including variables indicating the proportion of Russia stories clicked on (“Russia story clicks” ![]() $\div$ “Russia stories seen”) and a pre-treatment measure of portal usage.

$\div$ “Russia stories seen”) and a pre-treatment measure of portal usage.

Figure 7 Coefficient plots of partisans’ attitudes towards the media by the presence or absence of Trump-Russia scandal stories in respondents’ news portal

Note: Points and lines denote coefficient point estimates and 95% confidence intervals. Full regression includes four other experimental conditions; full results, including media trust variables, are available in table A4 of the online appendix.

We find no moderating effects of clicking on more Russia stories on the effects observed for Republicans, indicating that the observed shifts in Republican opinions are likely not explained by only those Republicans who read the stories on the Trump-Russia scandal. When controlling for clicks on Russia stories and portal usage, however, effects on Democrats shrink beyond the point of statistical significance. It matters whether Democrats read the scandal stories about Trump, but not Republicans: effects on Republicans endure, showing that scandals can alter the evaluations of a president’s co-partisans merely by changing the balance of headlines.

Conclusion

When Republicans saw relatively more stories about the Trump-Russia investigation, their attitudes and feelings about Trump changed in a consistently and significantly negative direction. Increased coverage of presidential scandal does not lead members of the president’s party to revise their opinions of the media, and the effects are not moderated by clicking on the stories. Media reporting on dominant stories, such as the Trump-Russia scandal, can lead members of the president’s party to assess the president more negatively and depress their positive feelings towards him. Though our findings cannot account for the impact of partisan media “bubbles” that may inhibit reception of scandal-related information, we show that—in the context of an online news feed—additional exposure to stories about presidential scandal does not lead to selective exposure or decrease evaluations of the mainstream media among co-partisans. When prominent scandals like Trump-Russia break through and become major stories, changing the balance of headlines, they have the potential to influence the opinions of members of the president’s party.

Members of the opposing party rated the president lower when exposed to more scandal news, as one might expect, but their reaction was comparatively muted relative to people in the president’s party. We interpret this as evidence of asymmetric partisan attitude strength: Democrats at the start of our study were far more certain of their negative views of Trump than Republicans were about their positive views. In each analysis, the largest effect of increased exposure to scandal news was among Republicans. Scandals depress the very citizens politicians hope to rely upon for support in their lowest moments. Partisans’ openness to revising their opinions suggests a more optimistic conclusion about the public’s capacity to respond to national news and events: a substantial number of partisans update their opinions when they receive information from the media, even when that information harms the leader of their party.

Our study is limited by several factors, and we leave multiple possible directions for future research. Though our study covers a full week, we only observed opinions during early June of 2017. The Trump-Russia scandal has only grown in magnitude since our study was in the field, as the Mueller investigation received the cooperation of Flynn, indicted Manafort and his associate Richard Gates, and interrogated Trump’s personal lawyer, Michael Cohen. We could not measure the impact of these later developments, or test whether Republican attitudes changed with this subsequent information. It is possible that, as the Trump presidency continued, Republican attitudes towards Trump became less ambivalent, and therefore less susceptible to change from new information. Additionally, though we focus on partisans in this article, we also find that Independents demonstrate backlash against scandal news and view President Trump more favorably when they see more Trump-Russia news. More work is needed on the dynamics of Independent response to scandal to determine whether this is a general dynamic or specific to Trump, a critical topic for future research.

The news portal also does not ensure reception, though we can measure portal usage. We did not restrict users to the portal alone and cannot rule out the possibility that they consumed other news that changed their attitudes. The tradeoff between forced exposure in a laboratory setting and repeated exposure in a realistic news context is difficult to resolve: our treatment is subtle, mimicking the changes in the overall news environment, and our effects are not substantively large as a result. The experimental design and survey measures also made participants aware they were under observation, and our request that they use the portal for the week may have caused them to use and process that information differently than under normal circumstances. This potential limitation to external validity is inherent to news consumption experiments. Concerns about this issue are partially addressed by several aspects of our design, such as respondents’ opportunity to consume the news (or not) in the manner of their choosing over the course of the week. We also find that portal use was not particularly heavy, as most participants logged on a few times during the week and saw only a handful of stories. Any potential cost to external validity is compensated by the certainty that our causal claims are an improvement on most observational research designs.

Future research should attempt to replicate the news portal approach within existing social media networks or across other news sources. Laboratory experiments could bolster the findings, as could survey evidence. Replication with another Trump scandal, such as potential emoluments clause violations or the sexual assault allegations from October 2016, would be helpful for determining the generalizability of observed effects. Further exploration of the relative immobility of Democratic respondents would also be valuable: might positive news about a president from the opposing party—for example, evidence of robust economic performance under Trump—impact Democrats instead, or are their attitudes too hardened? Republican losses in special elections also provide an opportunity: if Republicans view Trump’s scandals as an electoral disadvantage, that may amplify negative effects on his evaluations. It would also be valuable to determine the mechanism behind the moderating effects of news usage for out-party partisans but not co-partisans. It is possible, for example, that co-partisans are more attuned to the balance of headlines as they monitor public perceptions of their party’s leader.

Our study also suggests a renewed reason for concern about partisan news bubbles formed through selective exposure. If Republicans disregarded or counter-argued negative news about Trump regardless of exposure or dosage, then partisan news bubbles are less of a worry. We observe real effects of scandalous headlines about Trump among Republicans, however, which raises the stakes of selective exposure. There is evidence that conservative media is devoting relatively less coverage to Trump’s scandals, meaning Republicans may be less likely to see information that could otherwise change their attitudes (Mehta Reference Mehta2017). For example, in the hours following the FBI’s raid on Trump attorney Michael Cohen’s offices on April 9, 2018, Fox News devoted less than one-third the amount of airtime to the story as did MSNBC and CNN, while blaming the “out of control” Mueller investigation for the raid and minimizing references to Stormy Daniels’ role in the investigation (Chang Reference Chang2018). Selective exposure and partisan media may be minimizing some of the effects we observe in this study, since scandal reporting by co-partisan news appears to be lacking.

The implications for President Trump are clear: he cannot count on Republicans to support him blindly through the scandals plaguing his administration if those scandals remain prominently featured in headlines. Encountering scandalous news about Trump and Russia depresses Republicans’ feelings towards the president and decreases his approval ratings. In several special elections leading up to the 2018 midterm elections, lower Republican enthusiasm emerged as a prominent worry among national-level Republicans. If the Russia scandal continues to rage in the lead-up to Trump’s reelection campaign in 2020, those Republicans’ worries may be well-founded.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A: Technical Details of the Portal Design

Appendix B: Question Wording

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719001075