Introduction

The Mesozoa is an historic name given to two different groups of very small, vermiform and morphologically simple parasitic animals: the Dicyemida (=Rhombozoa), whose adults are made up of approximately 40 cells (Furuya and Tsuneki, Reference Furuya and Tsuneki2003); and the Orthonectida, which posses just a few hundred cells. As there is uncertainty over whether Dicyemida and Orthonectida form a monophyletic group, the Mesozoa grouping is now generally used informally rather than as a formal taxonomic assignment as a phylum. Both dicyemids and orthonectids are parasites of various marine animals: the dicyemids live in the renal tissue of cephalopods, whilst orthonectids occupy the internal body spaces of a variety of marine invertebrates, including brittle stars, bivalve molluscs, nemerteans and polychaetes.

Adults of both dicyemids and orthonectids have just two cell layers. Although they are multicellular, they lack defined complex tissues and organs and there is no evidence for the presence of true ectoderm or endoderm (Margulis and Chapman, Reference Margulis and Chapman2009). Adult mesozoans have an external layer of multiciliated cells, which facilitate movement, and at least one reproductive cell. Analysis of the orthonectid Intoshia linei found evidence for a simple nervous system, comprising just 10–12 nerve cells, and a simple muscular system, composed of four longitudinal and 9–11 circular muscle cells (Slyusarev and Starunov, Reference Slyusarev and Starunov2016).

In the 19th century, their simple body organization led to the idea that members of the Mesozoa – as their name suggests – were an evolutionary intermediate between the protozoans and the metazoans. More recent reassessment of mesozoan species indicates that they are in fact bilaterian metazoans that have undergone extreme simplification from a more complex ancestor (Dodson, Reference Dodson1956). In situ hybridizations for 16 diverse genes in different life stages of Dicyema japonicum suggested the presence of multiple different cell types, providing further support for the idea of a complex ancestor of Dicyemida, followed by extreme simplification of body organization (Ogino et al., Reference Ogino, Tsuneki and Furuya2011).

Two significant contributions for understanding the evolutionary history of the Mesozoa are the recent publication of the nuclear genome of Intoshia linei (Mikhailov et al., Reference Mikhailov, Slyusarev, Nikitin, Logacheva, Penin and Aleoshin2016), which represents one of approximately 20 species of this genus; and a transcriptome of Dicyema japonicum (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Kanda, Satoh and Furuya2017). The genomic sequence of I. linei is 43 Mbp in length and encodes just ~9000 genes, including those essential for the development and activity of muscular and nervous systems. Neither a phylogenomic analysis based on 500 orthologous groups nor an analysis of transcriptomic data from D. japonicum and a dataset compiled from 29 taxa and >300 gene orthologues, could confidently place the Orthonectida or Dicyemida in a precise position within the Lophotrochozoa. However, analysis by Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Kanda, Satoh and Furuya2017) found strong statistical support for a grouping of the Dicyemida with the Orthonectida in the phylum Mesozoa. A new and taxonomically broader phylogenomic analysis, however, found Intoshia to be nested within the annelids (Schiffer et al., Reference Schiffer, Robertson and Telford2018). While the position of Dicyema within the Lophotrochozoa could not be unambiguously resolved, it seems clear that Orthonectids and Dicyemida/Rhombozoa are not joined in a single taxon. Nevertheless, both of these groups can be regarded as examples of the extreme morphological and genomic simplification often found in parasites.

One resource that has not been extensively investigated to study the evolution and biology of the mesozoans is their mitochondrial genomes. Interestingly, the limited mitochondrial data analysed from Dicyemida to date suggest a highly unusual mitochondrial gene structure. The three mitochondrial genes that have been sequenced from D. misakiense (cox1, 2 and 3) appear to be on individual mini-circles of DNA, rather than being part of a typical circular mitochondrial genome (Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Bessho, Kawasaki and Hori1999; Awata et al., Reference Awata, Noto and Endoh2005; Catalano et al., Reference Catalano, Whittington, Donnellan, Bertozzi and Gillanders2015). Although the vast majority of metazoan mitochondrial genomes are found as a single circular molecule, a few multipartite circular genomes (that is, genomes where mitochondrial genes are found on more than one closed-circle molecule) have been reported across the Bilateria. The majority of these appear to come from parasitic species and multipartite mitochondrial genomes have been described, for example, from several species of lice (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Barker, Mitani, Aoki and Fukunaga2005; Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Yoshizawa, Mizukoshi, Whiting and Johnson2011; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Song, Guo, Jin, Yang, Barker and Shao2014) and parasitic nematodes (Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Brown, Howe, Peetz, Blok, Denver and Zasada2016). The Dicyemida could, therefore, represent another example of a parasitic organism with a multipartite mitochondrial genome.

Cox1 genes have been deposited in GenBank for a number of Dicyemida species, (D icyema koinonum; D icyema acuticephalum; D icyema vincentense; D icyema multimegalum; D icyema coffinense), but these have not been used in a published molecular systematic study.

In order to provide new mitochondrial gene data from these species, we looked for mitochondrial sequences in publicly available short read sequence data from members of the genus Dicyema (D. japonicum and Dicyema sp.) and Orthonectida (Intoshia linei). We compared features of the mitochondrial genome of I. linei to other metazoan members to shed additional light on its possible rapid and extreme simplification and used mitochondrial protein-coding gene data from Dicyema sp. and D. japonicum to investigate the internal phylogeny of the dicyemids.

Materials and methods

Genome and transcriptome assemblies

Genomic (I. linei: SRR4418796, SR4418797) and transcriptomic (Dicyema sp.: SRR827581; D. japonicum: DRR057371) data were downloaded from the NCBI short read archive. Adapter sequences and low-quality bases were removed from the sequencing reads using Trimmomatic (Bolger et al., Reference Bolger, Lohse and Usadel2014). The I. linei genome was re-assembled using the CLC assembly cell (v.5.0 https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/). The CLC assembly cell (v.5.0) and Trinity pipeline (Haas et al., Reference Haas, Papanicolaou, Yassour, Grabherr, Blood and Bowden2013) (v.2.3.2) were used to assemble the Dicyema sp. and D. japonicum transcriptomes, with default settings.

Mitochondrial genome fragment identification and annotation

Mitochondrial protein-coding gene sequences from flatworms were used as tblastn queries to search for mitochondrial fragments in the I. linei genome assembly and Dicyema sp. and D. japonicum Trinity RNA-Seq assemblies, using NCBI translation table 5 ‘invertebrate mitochondrial’. Positively identified sequences were blasted against the NCBI nucleotide database in order to detect possible contaminant sequences from Dicyema host species. For each Dicyema sp. gene-bearing contig, a number of other contigs were found that had very high sequence similarity to Octopus or other cephalopods, indicating a degree of host species contamination in the RNA-Seq data. These sequences were discarded from the subsequent analysis.

A 14 176 bp mitochondrial contig was identified from initial blast queries against the reassembled I. linei genome. An additional mitochondrial contig was found that overlapped with this 14 176 bp contig to extend the mitochondrial sequence of I. linei to 14 247 bp long. This final contig was annotated using MITOS (Bernt et al., Reference Bernt, Donath, Jühling, Externbrink, Florentz, Fritzsch, Pütz, Middendorf and Stadler2013). The locations of MITOS-predicted protein-coding genes were manually verified by aligning to orthologous protein-coding gene sequences taken from the published mitochondrial genomes of lophotrochozoan taxa. Where possible, the locations of protein-coding genes were inferred to start from the first in-frame start codon (ATN) and the C-terminal of the protein-coding genes inferred to be the first in-frame stop codon (TAA, TAG or TGA). Contigs from Dicyema sp. and D. japonicum identified as containing mitochondrial protein-coding genes were verified and annotated in the same way.

The secondary structure of tRNAs identified in the I. linei mitochondrial genome were inferred using the Mitfi program within MITOS. MITOS was also used to screen the Dicyema sp. and D. japonicum contigs which had been positively-identified as containing mitochondrial genes using blast. Using MITOS, we identified one reliable tRNA sequence for trnV on the same contig as cox3 from Dicyema sp. The secondary structure of this tRNA was also inferred using Mitfi in MITOS.

Dicyema internal phylogeny

cox1 nucleotide sequences from Dicyema sp. and D. japonicum were aligned to publicly available cox1 nucleotide sequences from other Dicyema species, and outgroup sequences from diverse lophotrochozoan taxa (see Supplementary Table S2). Sequences were aligned using Muscle v.3.8.31 (Edgar, Reference Edgar2004) visualized in Mesquite v.3.31 (http://mesquiteproject.org) and trimmed to remove uninformative residues with trimal v1.4.rev15. Maximum Likelihood inference was carried out for two trimmed alignments, one with all species, one with only the Dicyema species, using IQ-Tree (v.1.6.1) (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Schmidt, von Haeseler and Minh2015), letting the implemented model testing (ModelFinder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., Reference Kalyaanamoorthy, Minh, Wong, von Haeseler and Jermiin2017)) pick the best-fitting phylogenetic model (TVM + I + G4 and TIM + F + I + G4, respectively), and performing 1000 bootstrap replicates (UFBoot (Hoang et al., Reference Hoang, Chernomor, von Haeseler, Minh and Vinh2018)). The trees were visualized using Seaview v.4.4.2 (Gouy et al., Reference Gouy, Guindon and Gascuel2010) and annotated with Inkscape.

Data availability

All mitochondrial genome data presented in this study have been submitted to NCBI GenBank, under accession numbers: Intoshia linei mitochondrial genome sequence, MG839537; Dicyema sp. genes, MG839520-MG839528; D. japonicum genes, MG839529-MG839536.

Results

Intoshia linei mitochondrial genome composition

We assembled an I. linei mitochondrial genome sequence of 14 247 base pairs length but were unable to close the circular genome with paired-end reads. This could be attributed to the missing sequence being an AT-rich repetitive region, making it difficult to resolve. Furthermore, the I. linei mitochondrial genome we report is very AT-rich (83.40% AT).

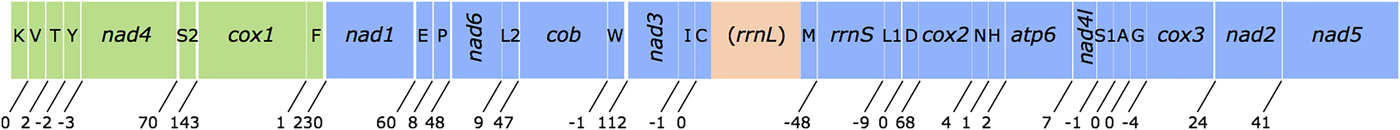

Using MITOS and manual verification, we were able to predict the full reading frames of 12 protein-coding genes, 20 tRNAs and the small subunit rRNA (rrnS). No sequences resembling atp8, trnQ or trnR could be found in the final sequence. It is possible that rrnL is found between trnC and trnM based on a weak prediction using MITOS, but this could not be confirmed by aligning to known rrnL sequences. Genes in the I. linei mitochondrial genome are found in two blocks of opposing transcriptional polarity: those in the first 3104 base pairs are found on the reverse strand (trnK-trnV-trnT-trnY-nad4-trnS2-cox1-trnF); all other genes are found on the forward strand, where the forward strand is defined as that containing a greater portion of the protein-coding sequences (Fig. 1, Table 1). All protein-coding genes have standard initiation codons (ATA × 8; ATG × 1; and ATT × 3). Ten of the protein-coding genes have a standard termination codon (TAA). nad5 and nad6 appear to have a truncated stop codon (T--and TA-, respectively) (Table 1).

Fig. 1. Overview of the mitochondrial sequence resolved for Intoshia linei. Genes not drawn to scale. Numbers beneath the sequences show intergenic spaces (positive values) or intergenic overlap (negative values). Protein-coding genes are denoted by three letter abbreviations; ribosomal genes by four-letter abbreviations. tRNAs are shown by single uppercase letters (for recognized codons of L1, L2, S1 and S2 see Table 1). Genes found on the negative (reverse) strand are coloured green; genes found on the positive (forward) strand are coloured blue. The unreliable prediction for rrnS is shown in orange.

Table 1. Organization of the I. linei mitochondrial genome. Uncertain position of rrnL shown in brackets. Recognized codons for tRNAs L1, L2, S1 and S2 indicated in brackets

Protein-coding genes account for 70.9% of the 14 247 base pair long sequence (allowing for overlap between genes); tRNAs 8.13%; rRNAs (including the uncertain prediction for rrnL) 13.83%; and non-coding DNA 6.85%. Four regions of non-coding sequence greater than 100 base pairs are found in the I. linei genome: a 143 bp-long region between trnS2 and cox1; 230 bp between trnF and nad1 (where the two genes are found on opposite strands); 112 bp between trnW and nad3; and 112 bp following the nad5 at the end of the genomic sequence. There is very little overlap between coding sequences: rrnS and the best prediction for the trnM location overlap by 48 nucleotides, and there are eight incidences of overlap of coding sequences of fewer than 10 nucleotides across the sequence.

In total 20 out of 22 typical tRNAs were identified in the I. linei mitochondrial genome (see Supplementary Fig. S3). All predicted tRNAs have an amino-acyl acceptor stem composed of seven or eight base pairs and an anticodon stem composed of four or five base pairs, with the exception of trnA and trnV, which appear to have truncated acceptor stems. The structure of the DHU arm is, for the most part, consistent with standard tRNA secondary structure: 14 of the predicted tRNAs have a typical four or five base pair DHU stem; four tRNAs have a truncated or modified DHU arm (trnI, trnL1, trnL2 and trnP); and two tRNAs appear to have lost the DHU arm entirely (trnS1 and trnS2). More unusually, the TC arm in almost all of the predicted tRNAs is either truncated or replaced by a TV loop. The only tRNA found to have a ‘typical’ TC arm structure is trnS2.

Gene order

The protein-coding and rRNA gene order of I. linei was compared with a number of other metazoan taxa using CREx (Bernt et al., Reference Bernt, Merkle, Ramsch, Fritzsch, Perseke, Bernhard, Schlegel, Stadler and Middendorf2007). Our analysis included representatives from across the Lophotrochozoa, Ecdysozoa and Deuterostomia (see Supplementary Table S1). CREx analysis aims to identify common gene intervals between different mitochondrial genomes, and infer the reversals, transpositions and reverse transpositions required to obtain an observed gene order from the mitochondrial gene orders of other species.

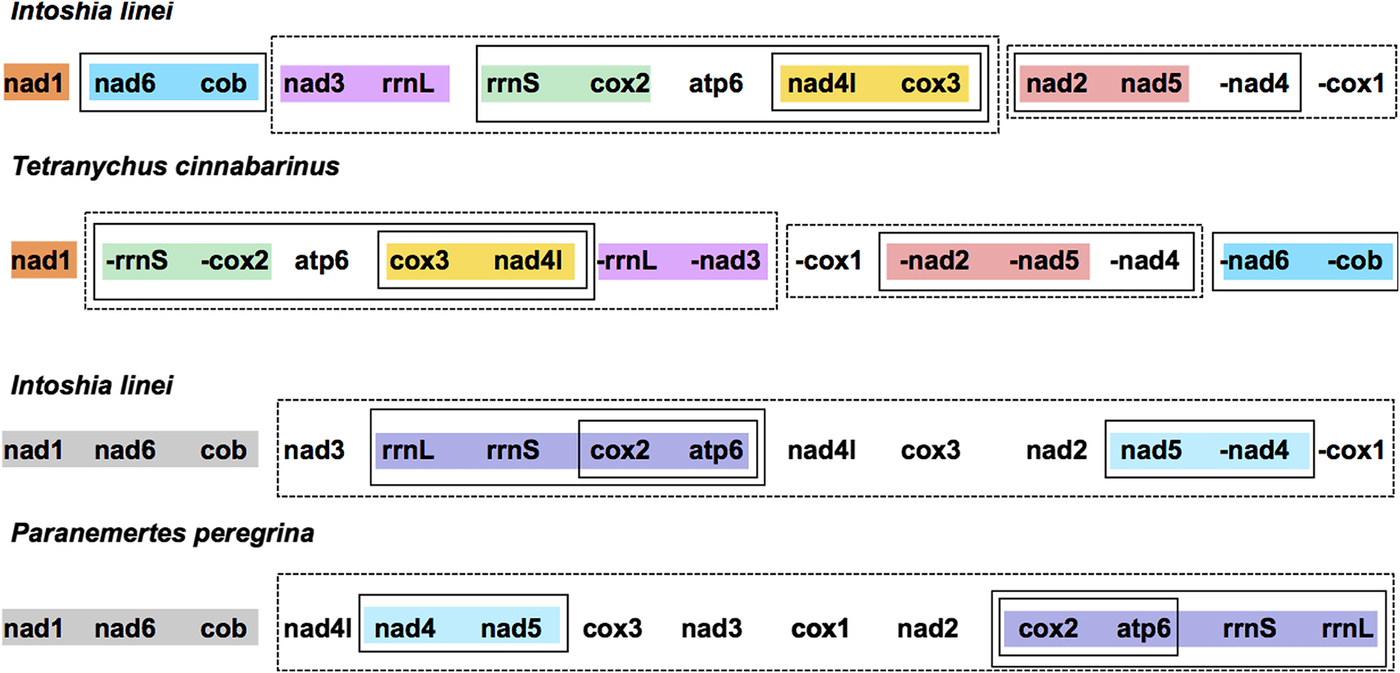

Compared with the other taxa included for analysis, I. linei has a highly divergent mitochondrial gene order. The species with the most similar gene order was the carmine spider mite Tetranychus cinnabarinus (Arthropoda; Chelicerata) (Fig. 2). However, the similarity in gene order between these genomes is low, with the two sharing just four short gene ‘blocks’ and with a degree of variation in gene order even within these conserved regions. Of the lophotrochozoan species included for analysis, the species with the highest similarity to I. linei was found to be the nemertean Paranemertes peregrina (Fig. 2). Both species share the common arrangement of nad1-nad6-cob, and the adjacency of rrnL-rrnS-cox2-atp6 and nad4-nad5, but with variation in the order of these two blocks. Overall, conservation of gene order between I. linei and P. peregrina is very low given the number of possible shared gene boundaries. It is clear that the gene order of I. linei is novel and very divergent compared with other published metazoan mitochondrial genomes.

Fig. 2. Gene order comparison between the mitochondrial genomes of Intoshia linei, the chelicerate Teteranychus cinnabarinus and the nemertean Paranemertes peregrina, as analysed using CREx. Genes on the minus strand are denoted by a minus sign (-X). Conserved blocks of genes between I. linei and T. cinnabarinus are shown in orange (nad1), blue (nad6, cob), pink (nad3, rrnL), green (rrnS, cox2), yellow (nad4l, cox3) and red (nad2, nad5). Variation in gene order and translocation between strands is found within these blocks between the two species. Conserved blocks of genes between I. linei and P. peregrina are shown in grey (nad1, nad6, cob), purple (rrnL, rrnS, cox2, apt6) and light blue (nad4, nad5). As before, variation in gene order and translocation between strands is evident between these common intervals. For both comparisons, solid or dashed-line boxes show larger regions of the genomes that encompass the same genes, but with no conserved gene order.

Dicyema sp. and D. japonicum mitochondrial genes

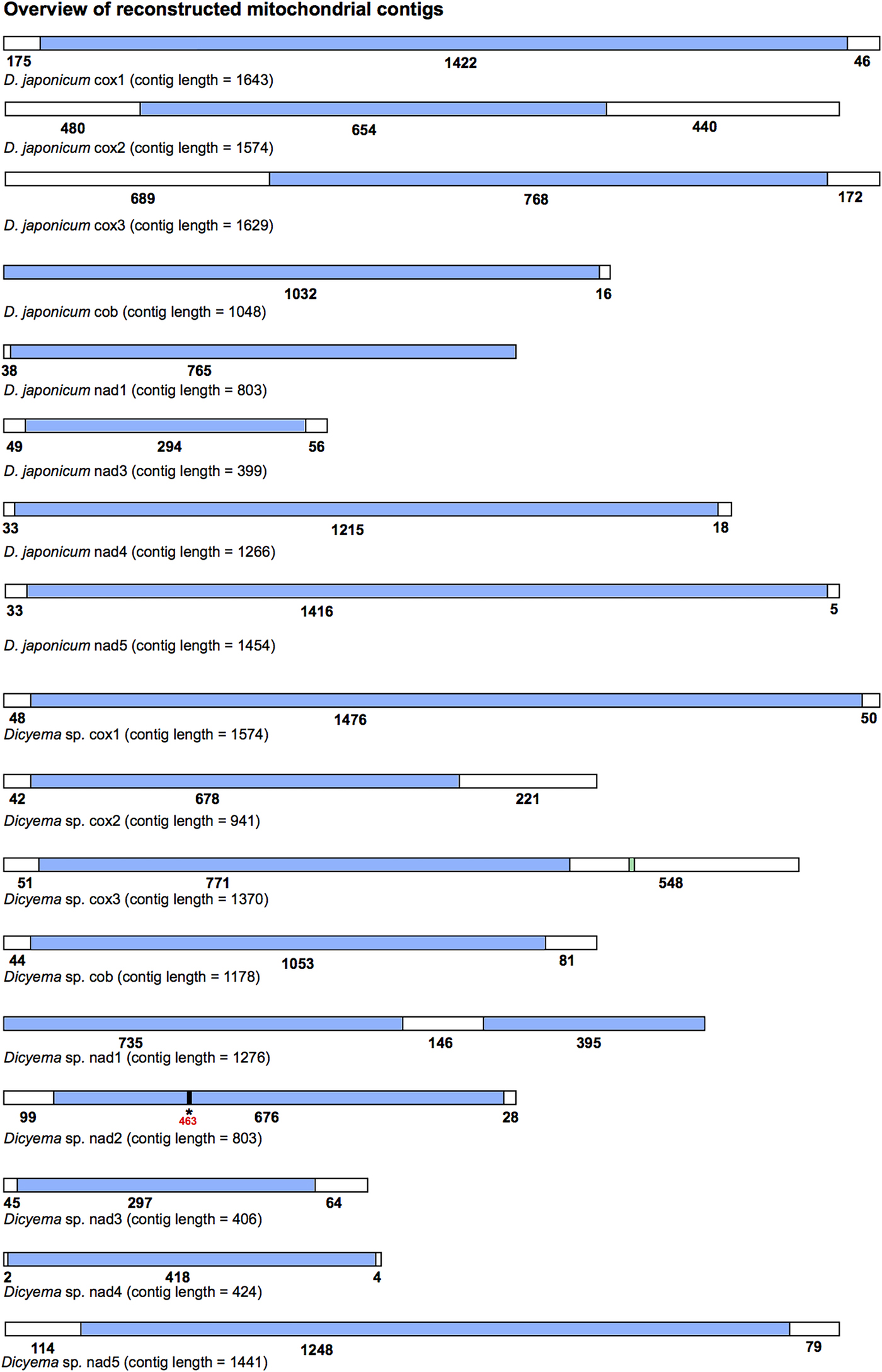

Using BLAST and manual sequence verification of contigs assembled using Trinity (Haas et al., Reference Haas, Papanicolaou, Yassour, Grabherr, Blood and Bowden2013) and the CLC assembly cell, we were able to identify nine reconstructed mitochondrial transcripts containing protein-coding genes from Dicyema sp. (cox1, 2, 3; cob; and nad1, 2, 3, 4 and 5). In D. japonicum we found contigs for eight mitochondrial transcripts of protein-coding genes (cox1, 2, 3; nad1, 3, 4 and 5; and cob). The identification of cob and nad3, nad4 and nad5 are novel for this taxon. All of the complete Dicyemida protein-coding genes identified have full initiation and termination codons, with the exception of D. japonicum nad1, which has a truncated TA stop codon.

All mitochondrial protein-coding genes found for Dicyema sp. and D. japonicum were located on individual contigs. In no instance were two or more protein-coding genes found on the same reconstructed transcript. However, each reconstructed mitochondrial transcript did contain non-coding sequence in addition to protein-coding gene sequence (Fig. 3). The length and location (5′ and/or 3′) of non-coding sequence in the reconstructed transcripts was variable between the two species and between genes (Fig. 3). For each protein-coding gene, we compared contigs assembled using both the CLC-assembler and Trinity in order to identify reconstructed mitochondrial transcripts with the longest stretch of protein-coding sequence. Of the 17 dicyemid genes we report, seven were derived from CLC-assembled contigs (cox1, 2, 3, nad3, 5 from D. japonicum and nad2, nad5 from Dicyema sp.) and ten from Trinity-assembled contigs (cob, nad1, 4 from D. japonicum and cox1, 2, 3, cob, nad1, 3, 4 from Dicyema sp.). The best reconstructed mitochondrial contig we identified for nad1 (Dicyema sp.) was found to contain duplicated stretches of the identical protein-coding gene sequence. We attribute this to an assembly artefact rather than speculating about this providing potential evidence for mitochondrial gene mini-circles. We also identified and corrected a frameshift in the coding sequence for nad2 from Dicyema sp. in the longest reconstructed mitochondrial contig from this species (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Overview of the reconstructed mitochondrial transcripts of protein-coding genes found in Dicyema japonicum and Dicyema sp. Transcripts are not to scale. Regions coloured blue indicate protein-coding sequence; regions coloured white indicate non-coding sequence. Numbers under each transcript correspond to the length of each respective coding or non-coding region, in base pairs. For cox3 in Dicyema sp. the location of the putative trnV sequence is shown in green (nucleotides 1130–1200). For nad2 in Dicyema sp., the location of a frameshift at position 463 in the longest coding sequence assembly is denoted by an asterisk (*).

By screening the Dicyema sp. gene-containing contigs with MITOS standalone software, we were able to predict one reliable tRNA sequence for trnV adjacent to cox3 (Fig. 3). Dicyema sp. trnV has an eight base pair acceptor stem; a five base pair anti-codon stem; and a four base pair DHU stem (Supplementary Information S3). As was found in I. linei, the TC arm appears to be modified from a standard ‘cloverleaf’ structure. In no other cases did we find any sequence from more than one gene on a single contig.

Dicyemida internal phylogeny using cox1

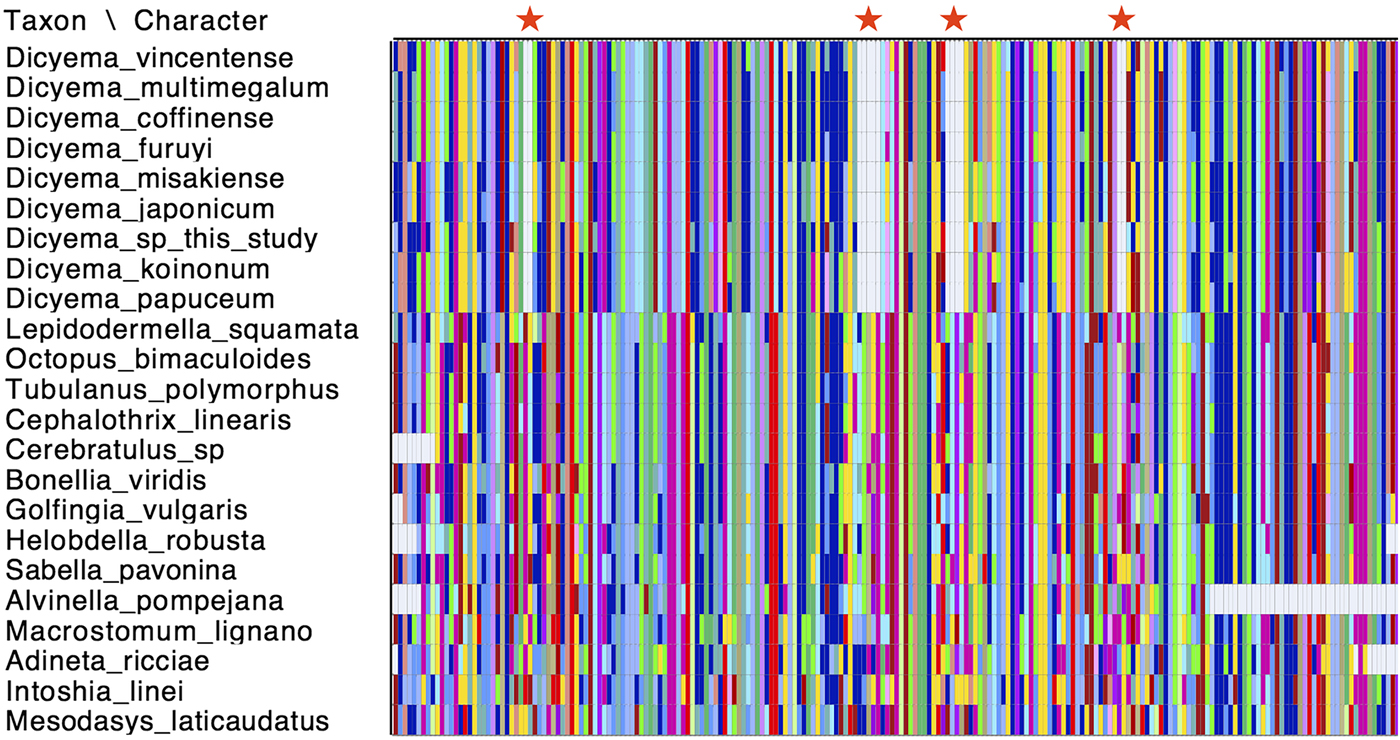

Cox1 is commonly used as a species ‘barcoding’ gene and can be used in phylogenetic inference to discriminate between closely related species (Hebert et al., Reference Hebert, Ratnasingham and deWaard2003). Given that a number of cox1 genes have been sequenced from different Dicyemida species, we used publicly available cox1 sequences along with the two new cox1 sequences found in this study for phylogenetic inference to determine the relationship of Dicyema sp. and D. japonicum to other dicyemids. After aligning the cox1 nucleotide sequences from dicyemids to other metazoans, we found that all Dicyemida cox1 sequences had several conserved deletions, not present in other metazoan cox1 sequences included in our alignment (Fig. 4). These comprise in-frame deletions of two, five, four and two amino acids moving from the N-terminus to the C-terminus of the protein. These deletions appear to be unique to members of the Dicyemida and were present in all Dicyemida species included in the alignment.

Fig. 4. Conserved deletions in the amino acid sequence of cox1 taken from publicly available dicyemid sequences (D. vincentense, D. multimegalum, D. coffinense, D. furuyi, D. misakiense, D. koinonum, D. papuceum) and the Dicyema species presented in this analysis (D. japonicum and Dicyema sp.), in alignment with other lophotrochozoan cox1 sequences. The location of the deletions (two amino acids; five amino acids; four amino acids and two amino acids) moving from the N-terminus to the C-terminus of the protein, are shown by red stars. Colours in the alignment correspond to amino acid colours as used by Mesquite v.3.31.

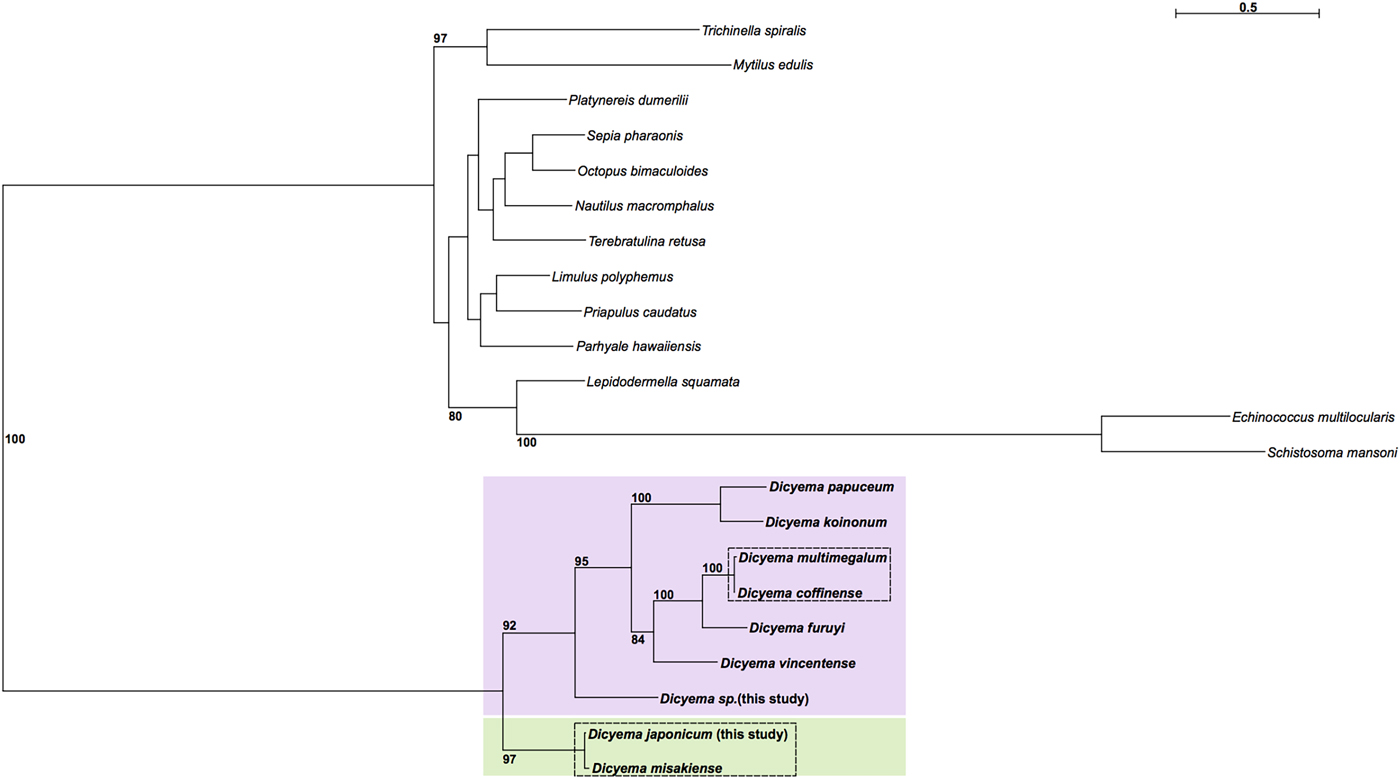

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis was carried out using cox1 sequences from publicly available Dicyema species; the D. japonicum and Dicyema sp. cox1 sequences assembled in this study; and cox1 sequences from a diverse representation of lophotrochozoans as outgroup taxa (Supplementary Table S2). As anticipated, the dicyemids included in analysis form their own branch on the tree. The topology of the subtree containing the Dicyemida species and the unrooted tree inferred from Dicyemida sequences alone is identical (Fig. 5). The analyses found a close affinity between D. japonicum with D. misakiense, with 97% bootstrap support at this node. At the nucleotide level, sequences from D. japonicum and D. misakiense are ~98% identical. The remaining Dicyema species branch into four groups, with the Dicyema sp. sequence from our analysis being an outgroup to the other six species. As found for D. japonicum and D. misakiense, the cox1 sequences from D. multimegalum and D. coffinense are ~98% identical at the nucleotide level (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Phylogenetic analysis of cox1 genes from dicyemids using Maximum Likelihood (IQ-Tree), including the two Dicyema species presented in this analysis (Dicyema sp. and D. japonicum). Cox1 sequences from diverse lophotrochozoan taxa included as outgroups (see Supplementary Fig. S4 for a tree based on the Dicyema species alone). Bootstrap support is shown at relevant nodes. Phylogenetic inference shows a split of dicyemid species into two groups, one containing D. japonicum and D. misakiense (green box) and the other containing all other dicyemid species included in analysis (pink box). Within the second group, Dicyema sp. is found on a separate branch from the rest of the included dicyemids. Very short branch lengths between both D. coffinense and D. multimegalum and D. japonicum and D. misakiense, indicate that they are very closely related or could be identical species (dashed-line boxes).

Discussion

Although the mitochondrial genome we found from I. linei is not a closed circular molecule, this represents the first mitochondrial genome from an orthonectid species and includes 12 protein-coding genes, 20 tRNAs and (possibly) both ribosomal RNAs. Atp8 was not found, but this gene has been lost from the mitochondrial genomes of taxa in many different metazoan lineages (Boore, Reference Boore1999) and so its absence from our assembly may be real rather than representing missing data. Compared with the drastically reduced I. linei nuclear genome, its mitochondrial genome has a gene complement that is fairly standard across the Metazoa (Mikhailov et al., Reference Mikhailov, Slyusarev, Nikitin, Logacheva, Penin and Aleoshin2016). Genes in the I. linei mitochondrial genome are clustered into two blocks of opposite transcriptional polarity. The block comprising trnK-trnV-trnT-trnY-nad4-trnS2-cox1-trnF at the ‘start’ of the sequence is found on the negative strand, whilst all other genes are transcribed from the positive strand, suggesting an inversion event (Fig. 1).

The ~84% A + T content found in the I. linei mitochondrial genome is high compared with other invertebrate mitochondrial genomes – for example, the chelicerate Limulus polyphemus (A + T content = 67.6%) (Lavrov et al., Reference Lavrov, Boore and Brown2000) and the annelid Lumbricus terrestris (A + T content = 61.6%) (Boore and Brown, Reference Boore and Brown1995). The very high A + T content of the mitochondrial genome is even higher than the high A + T content of the I. linei nuclear genome (73%), and provides evidence for the very fast rate of mitochondrial evolution in this species.

The small proportion of non-coding mtDNA we found for I. linei is typical of mitochondrial genomes. Although there is very little gene overlap in the sequence found for I. linei, the sequence for trnM is predicted with significant overlap with rrnS. Whilst it is possible that this is a mis-prediction, large gene overlaps have been reported in other mitochondrial genomes and this overlap could result from selection to minimize mitochondrial genome size (Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Lapraz, Egger, Telford and Schiffer2017).

Mitochondrial gene order can be a useful tool for inferring phylogenetic relationships. Gene order in the mitochondrial genomes of different lineages are largely stable, with the rearrangement of protein-coding genes occurring relatively infrequently. Where rearrangement events do occur, they are thought to be a result of tandem duplications and multiple random deletions. In this model, a portion of the mitochondrial genome is erroneously duplicated, and the subsequent random loss of one copy of a gene (by deletion or the accumulation of mutations) results in a novel gene order (Boore, Reference Boore, Sankoff and Nadeau2000). Comparing mitochondrial gene order between different taxa has been informative not only for the study of larger-scale evolutionary lineages (Boore et al., Reference Boore, Lavrov and Brown1998) but also for understanding the phylogeny of, for example, parasitic flatworms (Le et al., Reference Le, Blair, Agatsuma, Humair, Campbell, Iwagami, Littlewood, Peacock, Johnston, Bartley, Rollinson, Herniou, Zarlenga and McManus2000; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Shao, Li, Li and Zhu2013).

Our analysis demonstrated that I. linei has a highly divergent mitochondrial gene order in comparison with other published metazoan mitochondrial genomes. Of the species included – chosen as a broad representation of different metazoan lineages (see Supplementary Table S1) – the closest similarity was found to be to the chelicerate T. cinnabarinus (Fig. 2). However, of the highest possible conserved gene order score of 204 (that is, when two mitochondrial genomes have identical gene orders for the 12 protein-coding genes included for analysis (atp8 is not present in I. linei) and two rRNAs included in the CREx matrix calculation), similarity of gene order between I. linei and T. cinnabarinus was still poor, with a score of just 32. In light of the proposed affinity of I. linei to the Lophotrochozoa, the highest-scoring similarity to the lophotrochozoan species included in the analysis was with the nemertean P. peregrina. Again, these two species share comparatively little gene order conservation: just three common gene blocks were identified, one of which (rrnL-rrnS-cox2-atp6) has further rearrangement therein (Fig. 2). Of the common intervals identified, the block of nad1-nad6-cob is conserved between I. linei and P. peregrina and it is possible that this arrangement is plesiomorphic within the Lophotrochozoa.

Interestingly, previous analysis of five mitochondrial genomes from early branching annelids found that gene order was highly variable between these species (Weigert et al., Reference Weigert, Golombek, Gerth, Schwarz, Struck and Bleidorn2016). Other studies of various lophotrochozoan mitochondrial genomes – including Brachiopoda (Lingula anatina) (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Satoh and Endo2015); various Schistosoma species (Webster and Littlewood, Reference Webster and Littlewood2012); and nemerteans (Podsiadlowski et al., Reference Podsiadlowski, Braband, Struck, von Döhren and Bartolomaeus2009) – also indicate that extensive gene order rearrangements have occurred in different lophotrochozoan lineages. It is possible that the divergent gene order in I. linei can be associated with the parasitic lifestyle and rapid rate of evolution seen for this species: studies in a number of other parasitic taxa indicate that an accelerated rate of gene rearrangement in mitochondrial genomes could be associated with this lifestyle. For example, various Schistosoma species have mitochondrial genomes with a unique gene order (Le et al., Reference Le, Blair, Agatsuma, Humair, Campbell, Iwagami, Littlewood, Peacock, Johnston, Bartley, Rollinson, Herniou, Zarlenga and McManus2000) and this has also been observed in the ectoparasitic louse Heterodoxus macropus (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Campbell and Barker2001), various species of mosquito (Beard et al., Reference Beard, Hamm and Collins1993) and parasitic hymenopterans (Dowton and Austin, Reference Dowton and Austin1999), amongst others.

All of the tRNAs predicted from I. linei and the one tRNA found in Dicyema sp. have deviations from the ‘standard’ secondary structure of the TC arm (Supplementary Information S3). Although it is unusual amongst typical metazoan mitochondrial genomes to have such consistent modifications to one element of the tRNA cloverleaf structure, a great deal of variation can be found in tRNA structures across the Metazoa. Mitochondrial genomes with almost all tRNAs lacking either the TC arm or DHU arm – termed ‘minimal functional tRNAs’ – have been reported in a number of different lineages. In nematodes, analysis of tRNAs with TV loops in place of a TC arm suggests that an ‘L-shaped’ tRNA, analogous to a typical cloverleaf-structure tRNA – can maintain normal tertiary interactions and remain functional. Furthermore, it is likely that the tRNAs reported in this analysis are functional, as the acceptor stems and anti-codon stems are, for the most part, complete, and it is highly likely that they would have accumulated mutations should they have lost functionality. Instead, the reduction we observe in tRNA secondary structure could be a result of selective pressure to reduce the TC arm and provide another example of minimally functional tRNAs, in addition to those already found across the Metazoa.

Previous analyses had suggested that mitochondrial genes (cox1, cox2 and cox3) in dicyemids are found on individual mini-circles in somatic cells, as opposed to being located on a larger circular mitochondrial genome (Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Bessho, Kawasaki and Hori1999; Catalano et al., Reference Catalano, Whittington, Donnellan, Bertozzi and Gillanders2015). Mitochondrial mini-circles – although rare across the Metazoa – do appear to be most prevalent in parasitic species. A number of studies have reported the presence of mini-circle mitochondrial genomes, fragmented to various degrees, in a number of lice and nematode species (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Kirkness and Barker2009; Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Yoshizawa, Mizukoshi, Whiting and Johnson2011; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Song, Guo, Jin, Yang, Barker and Shao2014; Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Tsai, Coghlan, Reid, Holroyd, Foth, Tracey, Cotton, Stanley, Beasley, Bennett, Brooks, Harsha, Kajitani, Kulkarni, Harbecke, Nagayasu, Nichol, Ogura, Quail, Randle, Xia, Brattig, Soblik, Ribeiro, Sanchez-Flores, Hayashi, Itoh, Denver, Grant, Stoltzfus, Lok, Murayama, Wastling, Streit, Kikuchi, Viney and Berriman2016; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Brown, Howe, Peetz, Blok, Denver and Zasada2016).

We identified a mitochondrial contig for nad1 in Dicyema sp. that contained repeated nad1 protein-coding sequence. This could be an assembly artefact resulting from sequencing a circular nad1 molecule, but the question of the presence of mini-circles remains unresolved in our analysis. Further investigating the validity of mitochondrial mini-circles was outside of the scope of the present study, but future approaches involving long-range polymerase chain reaction or long-read sequencing should be conducted to resolve this question.

All dicyemid cox1 sequences were found to have a series of four in-frame deletions within a region of the gene that was well-aligned with cox1 sequences taken from other invertebrate species (Fig. 4). Insertions and deletions (indels) in genes are rare genomic changes that can be used to infer common evolutionary history (Belinky et al., Reference Belinky, Cohen and Huchon2010), but this set of conserved deletions are so far known only from the Dicyema genus. No such deletions are found in the I. linei cox1 gene, or in the same protein-coding sequence taken from across the Lophotrochozoa.

The internal phylogeny of dicyemids was inferred using Maximum Likelihood reconstruction based on cox1 gene sequences. Based on our analysis it is possible that D. coffinense and D. multimegalum are the same species, with both dicyemids isolated from Australian Sepia species (Catalano, Reference Catalano2013) and with a greater than 98% sequence similarity at the nucleotide sequence level. Our analysis also found a very close affinity for D. japonicum with D. misakiense, with 97% bootstrap support. As found for D. coffinense and D. multimegalum these cox1 sequences are >98% identical at the nucleotide level and it is thus likely that they are very closely related or the same species, both found in octopus living in the North West Pacific off the coast of Honshu Island, Japan. The Dicyema sp., despite being isolated from Sepia living off the coast of Florida, is a close sister to D. coffinense and D. multimegalum based on the similarities of the cox 1 assembled in this analysis, hinting at long-range dispersal with the host species. Further investigation into dicyemid members isolated from hosts in other geographical locations could help to inform whether the phylogenetic structure of the parasitic dicyemids is reflective of dispersal of the host octopus (Tobias et al., Reference Tobias, Yadav, Schmidt-Rhaesa and Poulin2017).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/pao.2018.12.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Telford and Oliveri labs at UCL for helpful comments on the analyses and manuscript.

Financial support

The research was funded by a European Research Council grant (ERC-2012-AdG 322790) to MJT.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.