One starting point for any discussion of Roman books and the possible existence of a papal library in the early Middle Ages is the number of references in seventh- and eighth-century narratives and letters to books from Rome reaching the British Isles, Francia and the Iberian peninsula. The books were brought both by English, Frankish and Spanish travellers and by visitors, couriers and legates from Rome. Bede (d.735), for example, records how Benedict Biscop (c. 628–c. 690), founder of the Northumbrian monastery of Jarrow, visited Rome six times and returned to Northumbria laden with books, for which he had either ‘paid a fitting price or was given them by friends’.Footnote 1 The life of Gertrude, abbess of Nivelles and great-grand-aunt of Charlemagne, similarly records the books and relics brought from Rome to Nivelles,Footnote 2 and Wandregisel, abbot of St Wandrille c. 649, sent his nephew Godo to Rome to obtain relics for the new monastery of Fontenelle near Rouen. Godo brought back biblical texts and the works of Gregory the Great as well.Footnote 3 The Spanish scholar Taio of Saragossa went to Rome c. 650 to fetch books, especially the works of Gregory the Great and Augustine, from which he compiled his Sententiarum libri quinque; Braulio of Saragossa asked Taio for copies of these same books. An account of Taio's visit to Rome is also preserved in the Chronicle of 754.Footnote 4

Gifts of books, including books in Greek, liturgical books and canon law, accompanied papal letters to the Frankish rulers, especially Pippin III and his son Charlemagne.Footnote 5 According to the preface to a substantial selection of these papal letters compiled on Charlemagne's orders in 791, the letters were transcribed into a parchment codex in order to preserve them.Footnote 6 Frankish copies of the Roman liturgical books, such as the Sacramentary made for Hadoardus of Cambrai (now Cambrai, Médiathèque Municipale, MS 164), sometimes record their Roman origin.Footnote 7

Some of the original books sent to England have survived and been identified, such as the late sixth-century St Augustine Gospels (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College Library, MS 286), probably brought by Augustine of Canterbury to England in 597, and a seventh-century papyrus fragment of the works of Gregory the Great (London, British Library, Cotton Titus CXV) (CLA II: *126, 192; Babcock, Reference Babcock2000: 6–15). Another example is the Durham Maccabees, a sixth-century fragment of another possibly Roman book (Durham University Library, B.IV.6), which provided the text and probably also a model for the script for the makers of the magnificent Codex Amiatinus at Jarrow at the beginning of the eighth century (Firenze, Biblioteca Medicea Laurentiana, MS Amiatino 1) (CLA II: *153; CLA III: 299; Lowe, Reference Lowe1960). The purple Gospels now in Paris (BnF lat. 11947), and the Cura Pastoralis of Gregory the Great (Troyes, Médiathèque Jacques Chirac Champagne Metropole, MS 504) appear to have been among the early arrivals from Rome in Frankish Gaul (CLA V: 616; CLA VI: 838; Clement, Reference Clement1985).

1. ROMAN SCRIPT

The lack of secure recognition of Roman script by modern scholars had greatly hindered the identification of other such volumes, and thus the potential role of Roman books in the dissemination of knowledge, until the Italian palaeographer Armando Petrucci (Reference Petrucci1971) proposed the notion of ‘Roman uncial’ in relation to the copy of Gregory the Great's Cura pastoralis now in Troyes.Footnote 8 Petrucci (Reference Petrucci2005) identified a small group of manuscripts from the late sixth and early seventh century with a similar kind of monumental uncial script to that in Troyes 504 (Fig. 1), as well as similar scribal discipline and preparation of the parchment. All these features were closely associated with the dissemination of the works of Pope Gregory I. Petrucci actually labelled the script ‘Lateran uncial’, and distinguished it from the script in other books he described as ‘urban Roman’.Footnote 9 A further group of ‘imitative copies’ of Gregory's works indicated their dissemination to Spain, Francia and northern Italy. In these Petrucci suggested that the uncial letter forms of the supposed exemplars were imitated by the scribes rather than copying the text in their local scripts, in a similar way to that already noted in relation to the fragment of Maccabees in Durham and the Codex Amiatinus.Footnote 10

Fig. 1. ‘Roman uncial’, Gregory the Great, Regula Pastoralis: Troyes, Mediathèque de l'agglomeration troyenne MS 504, fol. 4r, from CLA VI, Oxford, 1953, No. 838.

The identification of such a well-formed script in books dating to the turn of the sixth century might imply a script developed for the dissemination of the works of a particularly prolific author. Such an association has also been posited for the scriptorium of Wearmouth–Jarrow and the works of Bede (Parkes, Reference Parkes1982). In the case of Roman uncial, however, Petrucci (Reference Petrucci1971: 113) argued the case for a tradition of uncial script and book production already established in Rome and suggested that a number of early sixth-century codices with a sufficiently similar lapidary script might also be from Rome.Footnote 11 Petrucci nevertheless emphasized the considerable problems of identification in the late sixth and the seventh centuries; there appear to be insufficient grounds for proposing any coordinated Roman scriptorium in the sense defined by Giorgio Cencetti (Reference Cencetti1957: 196–7; compare Petrucci, Reference Petrucci1969, Reference Petrucci1992): that is, a place where the production of books and letter forms conformed to a single standard, as distinct from places ‘where the scribes were essentially free to write as they wished and in the types of script to which they were accustomed’.Footnote 12 Manuscripts written in half uncial such as the London Gregory fragment I mentioned above also need to be taken into account, though in his recent study of half uncial scripts Tino Licht is notably reticent on the location of any books in this script to Rome. He simply proposes (Reference Licht2018: 222–7) a possible impetus provided by the dissemination of the works of Pope Gregory I.Footnote 13 Nevertheless, some codices can be grouped according to a local or regional style with ‘analogous graphic characteristics’, some of which had other internal evidence suggesting production in various centres in and around Rome.

The continuity of a distinctive graphic tradition in codices with clear affinities with one another throughout the sixth century already suggests a centre or centres with conservative traditions. This continuity is stretched still further with Petrucci's suggestion that a group of codices from the late eighth and early ninth centuries should also be numbered among the books written in the script characterized as ‘Roman uncial’, albeit of a ‘decadent type’. This group included the two-volume Homiliary of Agimund, written for the church of the Santi Apostoli in Rome (BAV, Vat. lat. 3835 and 3836), the volume attributed to the subdeacon Juvenianus containing the Acts of the Apostles; the Epistles of James, Peter, John and Jude; the Book of Revelation; and the first book of Bede's Expositio Apocalypsis (Rome, Biblioteca Vallicelliana B.25), a collection of conciliar canons and papal decretals (BAV, Vat. lat. 1342), a volume containing the Epistles of Paul (BAV, reg. lat. 9) and, rather more cautiously, the Moralia in Iob (BAV, Vat. lat. 7809) (Cavallo, Reference Cavallo1991).Footnote 14 The script, style and layout of these manuscripts were characterized by Petrucci as the last flicker of a long and glorious graphic style. To these may be added the lost Farnesianus manuscript of the Liber pontificalis used by Francesco Bianchini for his edition in 1718, for which he commissioned engraved facsimiles of a few pages (Fig. 2). The codex contained the papal biographies at least up to the Life of Hadrian I (d.795) as well as a recension of the Life of Sergius II (844–7), recorded in no other manuscript. Although the latter may signal the use of Roman uncial until the middle of the ninth century, the script illustrated by Bianchini has closer similarities to the late eighth- and early ninth-century versions of Roman uncial identified by Petrucci. It is more likely, therefore, that the remarkable alternative, and hostile, version of the Life of Sergius II was added by a later hand, not necessarily in uncial. Unfortunately, Bianchini's notes are not specific enough to ascertain this.Footnote 15

Fig. 2. The uncial script of the lost Farnesianus manuscript, in the engraving commissioned and published by Francesco Bianchini in Bianchini, Reference Bianchini1718, II: lviii.

Later scholars have accepted implicitly the principle of continuity of Roman uncial from at least the beginning of the seventh century until the early years of the ninth century, even if both the location of some codices to Rome is disputed and the identity of the centres producing books written in this script remains elusive. Thus Paola Supino Martini (Reference Supino Martini1974, Reference Supino Martini1978, Reference Supino Martini1980, Reference Supino Martini2001) and Serena Ammirati (Reference Ammirati2007, Reference Ammirati, Carbonetti Vendittelli, Lucà and Signorini2015, Reference Ammirati, Ammirat, Ballardini and Bordi2020) have both augmented Petrucci's suggestions and discussed the appearance, from the second half of the ninth century, of Caroline minuscule in Roman books (see also Smiraglia, Reference Smiraglia1989; Schmid, Reference Schmid2002; Osborne, Reference Osborne2021). Some of these, such as the canon law collections now in Düsseldorf and Munich (Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek MS E1: Fig. 3; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Clm 14008) and Anastasius Bibliothecarius's translation into Latin of the decrees of the Council of Constantinople 869/70 (BAV, Vat. lat. 4965), can reasonably be associated with the Lateran, or at least Rome, though the latter codex also contains annotations made in the tenth century by Rather, bishop of Verona (Bischoff, Reference Bischoff and Bischoff1984: 11).Footnote 16 The earliest extant copy of Anastasius's translation of the second Council of Nicaea (787), however, is a Frankish copy dated to the third or fourth quarter of the ninth century (Paris, BnF lat. 17339, fols 3r–172v) (Bischoff, Reference Bischoff2014: 224 no. 5000). It is another instance of an echo of a book brought to Francia from Rome, for it appears to have been made from a copy of a Roman exemplar, containing Anastasius's own corrections, brought back from Rome by a Frankish bishop, Odo of Beauvais. The annotations in the now lost exemplar were incorporated into the main text in the Beauvais copy. A direct copy of Paris, BnF lat. 17339 was made in Reims before 882 and is also still extant (BAV, reg. lat. 1046).Footnote 17 Supino Martini and Ammirati have also drawn attention to other later ninth-century codices, such as John the Deacon's Life of Pope Gregory I (Tours, Bibliothèque Municipale 1027), Gregory's Cura pastoralis (BAV, Santa Maria Maggiore 43), a Gospel book (BAV, Santa Maria in via Lata I 45), an Octateuch fragment (Oslo/London, Schøyen Collection MS 20/1) from a scriptorium of Santa Cecilia s.IX/2, an Epitome Juliani (Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Cod. 2160) and the glossary chrestomathy in BAV, Vat. lat. 3321, all of which may represent instances of work from various centres in Rome. There are some doubtful attributions whose origin is disputed, such as a canon law collection in Rome (Biblioteca Vallicelliana A5), the Historia mystica of Maximus the Confessor (Cambrai, Mediathèque MS 803) and a compilation of grammatical texts in Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek Class. 43.

Fig. 3. Roman minuscule, Canones (Collectio Vaticana combined with Dionysio-Hadriana): Düsseldorf Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek HS E.1 (Leihgabe der Stadt Düsseldorf an die Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Düsseldorf), fol. 2v. Reproduced with the kind permission of Marcus Vaillant, of the Düsseldorf Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek.

These studies have further enriched our understanding of all these books. Art historians, notably Florentine Mütherich (Reference Mütherich1976), Maria Bilotta (Reference Bilotta2011) in an important study of the papal library in the Middle Ages, and of course John Osborne (Reference Osborne1990, Reference Osborne2023), have strengthened the case on stylistic grounds for their being produced in Rome. Osborne (Reference Osborne2020) in particular has highlighted the importance of the Roman manuscript made c. 800 of Pope Zacharias's Greek translation of Gregory I's Dialogues (BAV, Vat. gr. 1666). More recent work on the Greek-speaking communities in Rome in the seventh and eighth centuries has exposed further possibilities, but I shall return to the topic of Greek and Greek-speakers below.

This small corpus of evidence prompts a number of comments. The level of expertise they represent, the suggestion of established and well-maintained traditions of writing, decoration and the presentation of texts, and the types of text the books contain — biblical, liturgical, canon law and papal writings — all imply institutions possessed of considerable resources and longevity. The implications of the practical production of such substantial and professionally written and decorated codices in one city enhance this impression, if understood in terms of the supply and storage of writing materials — parchment and papyrus, ink, pens and pigments — the procuring of exemplars or contact with authors for contemporary work, the training and supervision of local scribes and the possibility of scribes trained somewhere else but working in Rome, the physical structures in which the work may have taken place, and the networks for sale, commissioning or distribution of the work once completed.Footnote 18 We need to think about how scribes were trained and where. What are the possible centres in which books might have been produced? Were there bookshops? Were there secular centres of book production? Did monasteries as well as other churches besides the Lateran church commission or produce books? How does book production sit alongside the production of legal documents in Rome in this period (Toubert, Reference Toubert2001; Carbonetti Vendittelli, Reference Carbonetti Vendittelli, Braidotti, Dettori and Lanzillotta2009, Reference Carbonetti Vendittelli, Martin, Peters-Custot and Prigent2011)? What relationship is there between scribes of books and the stonecutters who cut the inscriptions from this period that abound in Rome, or those who devised the lettering on the mosaics and frescoes (Silvagni, Reference Silvagni1943; Gray, Reference Gray1948; Cardin, Reference Cardin2008)?

There has been a strange preference in the scholarly literature for monastic communities as producers of books and guardians of libraries, and a reluctance to concede a role for Roman, let alone papal, centres. The difficulties of identification and disappearance are not the only obstacle. The original books in Cassiodorus's library at the monastery of Vivarium have almost entirely disappeared despite the sterling efforts of some scholars to identify them (Troncarelli, Reference Troncarelli1988, Reference Troncarelli1998). The bibliographical discussion offered by Cassiodorus in his Institutiones has also dominated discussions to such an extent that Vivarium has tended to become the default symbol of cultural resilience in the supposed transition from antiquity to the Middle Ages (Halporn and Vessey, Reference Halporn and Vessey2004).

A further problem exposed by the discussion of Roman books is the yawning gap of 200 years between the books associated with Gregory the Great at the beginning of the seventh century and the Homiliary of Agimund at the end of the eighth century. That books were produced in Rome cannot be doubted, for there are many Frankish and north Italian copies of texts composed and compiled in Rome in these two centuries. Indeed, one of the peculiarities of the surviving evidence is that so few original Roman manuscripts or fragments from before the late eighth century, as distinct from copies made outside Rome and mostly north of the Alps, have been identified. That is, most of the earliest manuscript witnesses to the works of classical and late antique authors (Ganz, Reference Ganz2002; McKitterick, Reference McKitterick2017), Roman liturgy (such as the copy of the Hadrianum sacramentary mentioned above),Footnote 19 ordines (Sorci, Reference Sorci and Salvarani2011; Romano, Reference Romano2019; Westwell, Reference Westwell2019), canon law, papal letters and decretals, papal sermons, doctrinal and exegetical works, papal history, Roman martyr narratives and Roman legendaries cannot be identified as Roman or even Italian. Among the most striking instances of such an anomalous distribution of Roman books are the copies of the Dionysiana collection of canon law produced in Rome c. 500 (a bilingual Latin and Greek version of which was commissioned by Pope Hormisdas in the early sixth century) and updated by Pope Hadrian at the end of the eighth century (Collectio Dionysiana ed. Strewe; Kéry, Reference Kéry1999), and the Liber pontificalis, the history of the popes in the form of serial biography from St Peter onwards, composed within the papal administration in Rome in the early sixth century with continuations added in the seventh, eighth and ninth centuries. Despite their Roman origin, the earliest surviving examples of the full text of the Dionysio-Hadriana collection of canon law and of the Liber pontificalis are not from Rome but from Francia (McKitterick, Reference McKitterick2020a: 171–223). Studies of early medieval authors have surmised that the exemplars at least of the wealth of classical and patristic writings these authors cite explicitly or to which they appear to have recourse may also have come from Rome. Studies of early medieval English authors have been the most optimistic in this respect. Others accord a greater contribution to the English from Gaul, but of course for Roman texts the ultimate source for those as well was presumably Italy, if not Rome itself.Footnote 20

From all this a number of questions emerge. Rome was certainly recognized as the place to go for books, but references are rarely more specific, apart from that concerning Benedict Biscop, who bought or was given books in Rome, and the gifts to the Frankish kings Pippin III and Charlemagne where papal resources are implied. None refers explicitly either to a papal library or to a centre of papal book production, whether within the Lateran itself or in one of the group of monasteries serving the Lateran founded by the popes or elsewhere in Rome. The existence of such a repository as well as production centre(s) is simply implied. But, where were they? Was there a papal centre of book production? Is it to be identified with the papal writing office or scrinium? Were scrinium, archive and bibliotheca all part of a single complex? If so, where might it have been?

The production of books related to the dissemination of the works of Pope Gregory the Great, together with the particular examples I have cited, suggest exceptionally well-organized and professional scribes and all the related infrastructure of book production for the provision of writing materials, the training of scribes and distribution. The role of books from Rome as models for imitative copies in terms of script, layout and codicological practice touched on by Petrucci merits far deeper investigation than is possible here. Again, the extant evidence of such copies, as well as the late eighth- and ninth-century copies of texts produced in Rome earlier, in the seventh and early eighth centuries, also implies no break in the steady production of Roman texts and Roman books. Further, the identification of books produced in Rome has rarely gone further than their script and decoration. I do not have space to consider the range of scripts, including capitals, uncial, half uncial and cursives, used in early medieval Italy, though as I have already indicated, there is much excellent work published and in progress (Falluomini, Reference Falluomini1999; Bassetti, Reference Bassetti2023a, Reference Bassetti2023b). The attention given to Roman books and Roman script, with the confident identification of both the Gregory I era and Roman books of the late eighth century, nevertheless, as I have indicated, leaves a disconcerting gap between these two eras and appears to expose an unusual degree of graphic continuity. Such continuity cannot logically be apparent unless there was also continued activity in book production in the intervening period, that is, the seventh and eighth centuries. The texts these codices actually contain also need to be considered, not only for what they tell us about the availability of texts in Rome, but also what such texts may imply about the interests they represent. In particular, the significance of and contexts for the Greek texts need further consideration. Lastly, there are the broader questions of Rome's role in the dissemination of knowledge, the potential function of a papal library, and why this might be significant both in general terms, and in relation to the representation and demonstration of papal authority, the popes' championing of orthodoxy, and the degree to which the popes are represented as successors to the emperor. In the remainder of this paper, I shall discuss one case study from the seventh century which may shed some light on all these questions, but before I do so it is worth looking briefly at the questions of the papal writing office or scrinium and the possible location of a papal library.

2. THE PAPAL WRITING OFFICE OR SCRINIUM AND THE POSSIBLE LOCATION OF A PAPAL LIBRARY

The references to books in and from Rome with which I began this paper can be augmented by allusions to the resources of the papal archive. The most famous of these is Bede's report of Nothelm of Canterbury who went to Rome and was permitted by Pope Gregory II (715–31) to search through the archives of the holy Roman church (sanctae ecclesiae Romanae scrinio), where he found ‘some letters of the blessed Pope Gregory [I] and other popes’.Footnote 21

The authors of the Liber pontificalis, who were, as already stated, members of the papal administration, provided a perhaps over-generous chronology for the creation of the scrinium by crediting it to the fourth-century pope Julius:

[Julius] issued a decree that no cleric should take part in any law suit in a public court, but only in a church; that the documents which had everyone vouching for his holding the church's faith should be gathered in by the notaries; and that the drawing up of all documents in the church should be carried out by the primicerius notariorum — whether they be bonds, deeds, donations, exchanges, transfers, wills, declarations, or manumissions, the clerics in the church should carry them out through the church office.Footnote 22

Additional functions and categories of material accrued, not least the drafting and archiving of papal letters. The Liber pontificalis, for example, notes that the letters of Pope Leo I were kept in archivo or scrinium, and it was from the archived copies (reputedly fourteen rolls) of the letters of Gregory the Great that the Registrum volume of a substantial selection of over 600 letters was compiled in the scrinium under Pope Hadrian I at the end of the eighth century, though the Registrum only survives in Frankish copies of the ninth century.Footnote 23 The papal record system appears in fact to have been very versatile. When Arator recited his long poem on Peter and Paul in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli c. 544, for example, it was presented publicly and dedicated to Pope Vigilius. The preface supplied by Surgentius the primicerius of the notaries as he entered the codex into the papal register is preserved in the ninth-century copies of the poem, such as Paris, BnF lat. 8095, fol. 2 (Arator, ed. Orban: 5–6; McKinlay, Reference McKinlay1942; Reference McKinlay and McKinlay1951: xxviii; Hillier, Reference Hillier2020). When Pope Zacharias presided over the Synod of Rome held in the Lateran palace and basilica of Theodore in 745, one of the items of business was how to deal with the fantastical claims of two missionary preachers in Germany called Aldebert and Clemens. The synod wanted the texts to be destroyed but Zacharias ruled that ‘the writings of Aldebert [and Clemens] deserve to be burned with fire but as a means of confuting them it will be well to preserve them in our sacred archives for his perpetual condemnation (in sancto nostro scrinio reserventur ad perpetuam eius confusionem)’.Footnote 24 Such references can easily be multiplied and the legal documentation emanating from the papal writing office is also very well attested, not least in the contents of the Liber Diurnus or day book with sample papal documents from the seventh and eighth centuries (Santifaller, Reference Santifaller1953; Rabikausas, Reference Rabikausas1958; Toubert, Reference Toubert2001).

References to a library using the word bibliotheca are less common, but the description in the Liber pontificalis (ed. Duchesne: 245) of the establishment by Pope Hilarus of one or two libraries at a church of St Lawrence, probably the oratory of St Lawrence at the Lateran,Footnote 25 the founding of a library by Pope Agapetus on the Caelian hill near the Lateran recorded in an inscription preserved in the Codex Einsiedlensis (Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek Cod. 326), and whose remnants are still claimed as the biblioteca today (Walser, Reference Walser1987: 47; Franklin, Reference Franklin and Hamesse1998; Halporn and Vessey, Reference Halporn and Vessey2004: 24–7), and Pope Gregory I's response to a request for a book of the acts of the holy martyrs, that he was ‘not aware of any collections in the archives of this our Church, or in the libraries of the city of Rome, unless it be some few things collected in one single volume’ (nulla in archivio huius nostrae ecclesiae vel in Romana urbis bibliothecis esse cognovit, nisi pauca quaedam in unius volumine collecta),Footnote 26 are often cited in modern surveys for the sixth and seventh centuries (Clark, Reference Clark1902; Winsbury, Reference Winsbury2009; König et al., Reference König, Oikonomopoulou and Woolf2013).

Further, the later recension of the Life of Gregory II (715–731) notes that as a member of the papal household in the time of Pope Sergius I (680–701) he was made a subdeacon and sacellarius and put in charge of the library (Liber pontificalis, ed. Duchesne: 396; Davis, Reference Davis2007). In ninth-century Roman sources there are further references to individuals with the title of bibliothecarius, such as Megistus, and Anastasius bibliothecarius (Winterhager, Reference Winterhager2020: 262, 333).

There seems to be sufficient evidence for a papal collection of books, though it is not clear whether it was part of the papal archive, a reference collection attached to the scrinium in some way, or with a separate identity as a bibliotheca. Where such a collection might have been is another matter, but since the discovery by the young Philippe Lauer in 1900 of an early medieval fresco portrait of an author and a painted inscription, the focus has been on the undercroft of the sancta sanctorum in the Lateran complex (Fig. 4). Lauer was only able to excavate a narrow tunnel (Fig. 5), and his report remains the tantalizing starting point for speculation.Footnote 27 The portrait apparently of a writer could be an early medieval equivalent of the busts or medallions of ancient authors ornamenting the ancient libraries mentioned by a number of classical authors in describing the imperial libraries in Rome. Pliny (Natural History 35.2.9–10) for example referred to ‘likenesses … set up in the libraries in honour of those whose immortal spirits speak to us in the same places’.Footnote 28 Remnants of such portraits were found in the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum (Clark, Reference Clark1902; Houston, Reference Houston, König, Oikonomopoulou and Woolf2013),Footnote 29 and are to be found portrayed in imaginative reconstructions.Footnote 30

Fig. 4. Plan of the excavation under the sancta sanctorum, showing the position of Philippe Lauer's tunnel, from Lauer (Reference Lauer1900).

Fig. 5. The tunnel excavated by Philippe Lauer in the foundations of the sancta sanctorum, from Lauer (Reference Lauer1900). ‘Z’ on the far left of the plan marks the position of the fresco portrait of an author illustrated in Figure 6.

Fig. 6. Portrait of an author: Augustine? Jerome? discovered by Lauer in his excavations under the Scala Santa and reported in Lauer (Reference Lauer1900); from the colour copy made by Wilpert (Reference Wilpert1931).

The portrait found by Lauer and published in colour by Joseph Wilpert (Reference Wilpert1931) (Fig. 6) need not be of Augustine as supposed (Redig de Campos, Reference Redig de Campos1963). John Osborne (Reference Osborne, Brandt and Perhola2011; Reference Osborne2020: 144–6) has suggested that it could just as well be of Jerome. The date of the fresco has also been disputed, with a range from the sixth to the eighth centuries. Again, it is Osborne who has drawn attention to parallels between the decorative elements and the letter forms as well as the style of the portrait and those in the Theodotus chapel of Santa Maria Antiqua; these would suggest an eighth-century date for the painting. This would coincide with the building of a tower and portico and other painting activity commissioned by Pope Zacharias and recorded in the Liber pontificalis (ed. Duchesne: I, 432; Osborne, Reference Osborne and Cubitt2003). A mid-eighth-century date, however, does not preclude all these additions and decoration as restorative work to an already existing structure and space. The inscription's mention of the eloquence of the Roman tongue has also led to the suggestion that this was a reference to collections of books in Latin with another, separate, library of Greek texts implied. If the small decorated space Lauer found under the sancta sanctorum, which is also in proximity to the oratory of St Lawrence, was indeed a corner of a much larger space and thus where the papal library might have been located, it raises questions of how it fitted into the other buildings that archaeologists, and interpreters of later medieval and early modern descriptions and illustrations, have been able to propose for this part of the Lateran site. Luchterhandt's (Reference Luchterhandt, Stiegemann and Wemhoff1999) reconstruction, reflecting the Lateran palace of 1585, has been adapted to indicate the relevant early medieval buildings by Hendrik Dey (Reference Dey2021: 119; cf. Ballardini, Reference Ballardini2015) (Fig. 7), but we await now the outcome of the more recent archaeological excavations and interpretation in train under the leadership of Paolo Liverani and Ian Haynes as part of the RomeTrans project (Liverani, Reference Liverani and Liverani2004; Bosman et al., Reference Bosman, Haynes and Liverani2020).Footnote 31

Fig. 7. Suggested reconstruction of the Lateran complex in the early Middle Ages, adapted from Luchterhandt (Reference Luchterhandt, Stiegemann and Wemhoff1999, Reference Luchterhandt, Featherstone, Spieser, Tanman and Wulf-Rheidt2015) and Dey (Reference Dey2021). The buildings marked A = the sancta sanctorum chapel; B = Pope Zacharias's vestibule and stairway leading to the elevated portico; C = Pope Zacharias's triclinium; D = towers added by Pope Zacharias (d.752) or Pope Hadrian (d.795); E = first triclinium of Pope Leo III (d.816); F = Pope Leo III's raised loggia overlooking the campus Lateranensis; G = Pope Leo III's second triclinium (the aula concilii). Reproduced with the kind permission of Manfred Luchterhandt and Hendrik Dey.

It is interesting to compare the reconstruction and location of a possible Lateran library and/or scrinium in proximity to the sancta sanctorum in the oratory of St Lawrence and the Lateran basilica with the position of the ground-floor scriptorium and first-floor library on the St Gall plan, an idealized monastic layout drawn c. 820 (Fig. 8).Footnote 32 There, library and scriptorium are also juxtaposed to the sancta sanctorum and crypt of the monastic basilica where the holy relics of the saints are to be housed. A papal scrinium can perhaps be imagined in some kind of proximity to the book collection. That collection in the sixth, seventh and eighth centuries presumably included papyrus rolls as well as codices, so we might need to envisage a scenario that combined a space for a scriptorium and book containers for both rolls and codices, similar to those long familiar from the famous (now lost) third-century sculpture in Trier of a bookshelf with rolls (Schubart, Reference Schubart1961: 73), the bookcase in the mosaic of the martyrdom of St Lawrence in the Oratory of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, or the bookcase behind the seated Ezra portrayed in the Codex Amiatinus.Footnote 33

Fig. 8. Plan of St Gallen (Stiftsbibliothek csg 1092) from the first quarter of the ninth century. The detail shows the proximity of the two-storey structure with the library and scriptorium (Infra sedes scribentiu(m); Supra bibliot(h)eca) to the sancta sanctorum below the high altar in the basilica. Reproduced with the kind permission of Cornel Dora, Stiftsbibliothekar.

Such imaginative speculation of course rests on mere fragments, but greater credibility may be added if we return now to the literary evidence and consider the implications of the proceedings of the Lateran Council of 649 as evidence for the contents of the papal library in Rome.

3. THE LATERAN SYNOD OF 649

The Lateran Synod in 649 (ed. Riedinger) comprised five sessions held between 7 and 31 October and was convened to resolve the Monothelite controversy. The dispute was primarily between those who asserted a single operation and will in Christ and those who affirmed two operations and two wills, corresponding to his two natures, divine and human.

Like other early acta of ecclesiastical councils, the proceedings are presented as a report of the sessions, day after day (Graumann, Reference Graumann2021). They often include an overall summary which comes immediately after the record of those attending. The acta which follow are summaries of the debates, often with each protagonist named and direct speech reported, in which the person speaking alludes to or quotes, sometimes at length, from many biblical passages and patristic authorities in support of his arguments. Documents are requested, produced and read out to those assembled.

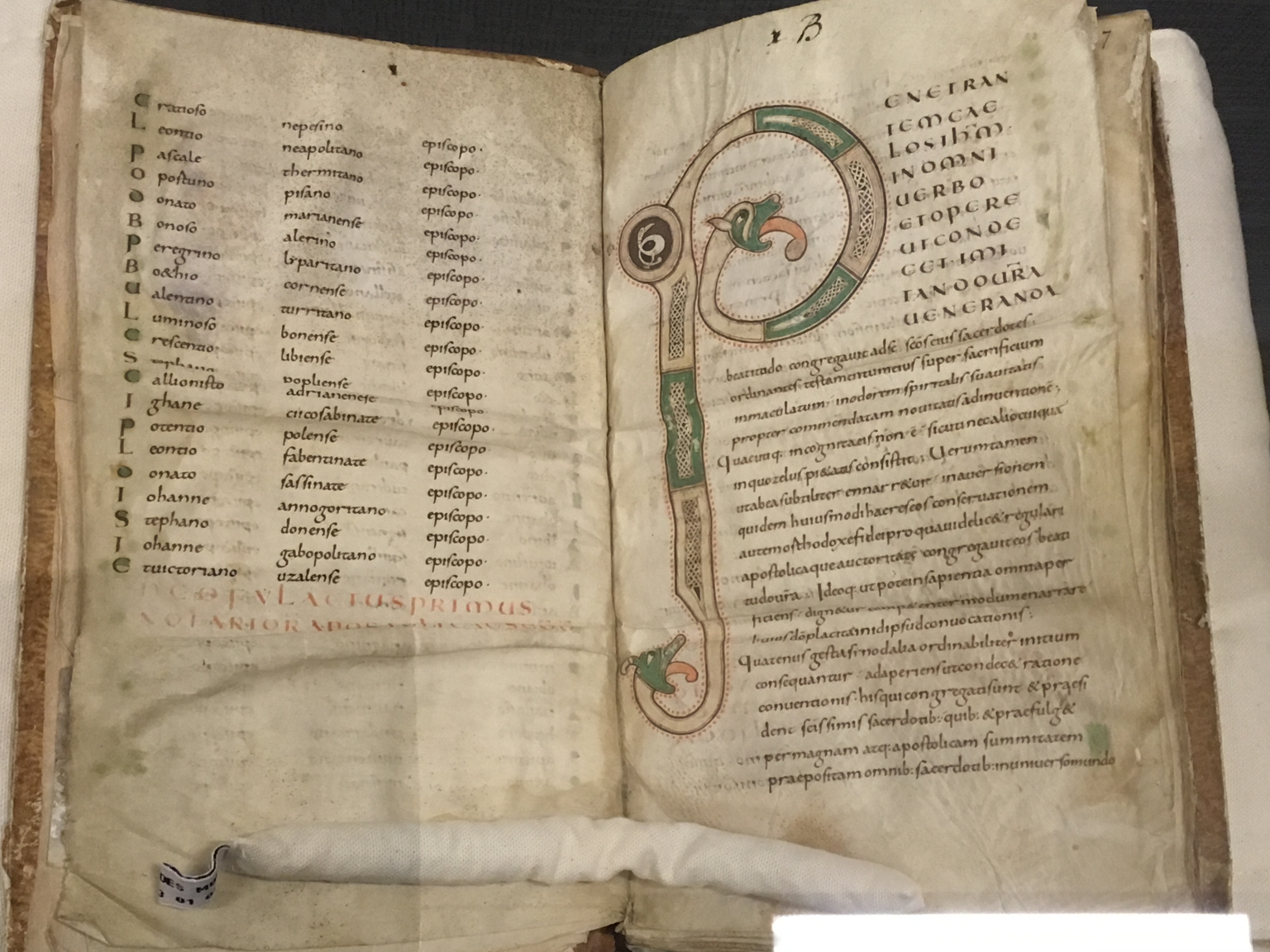

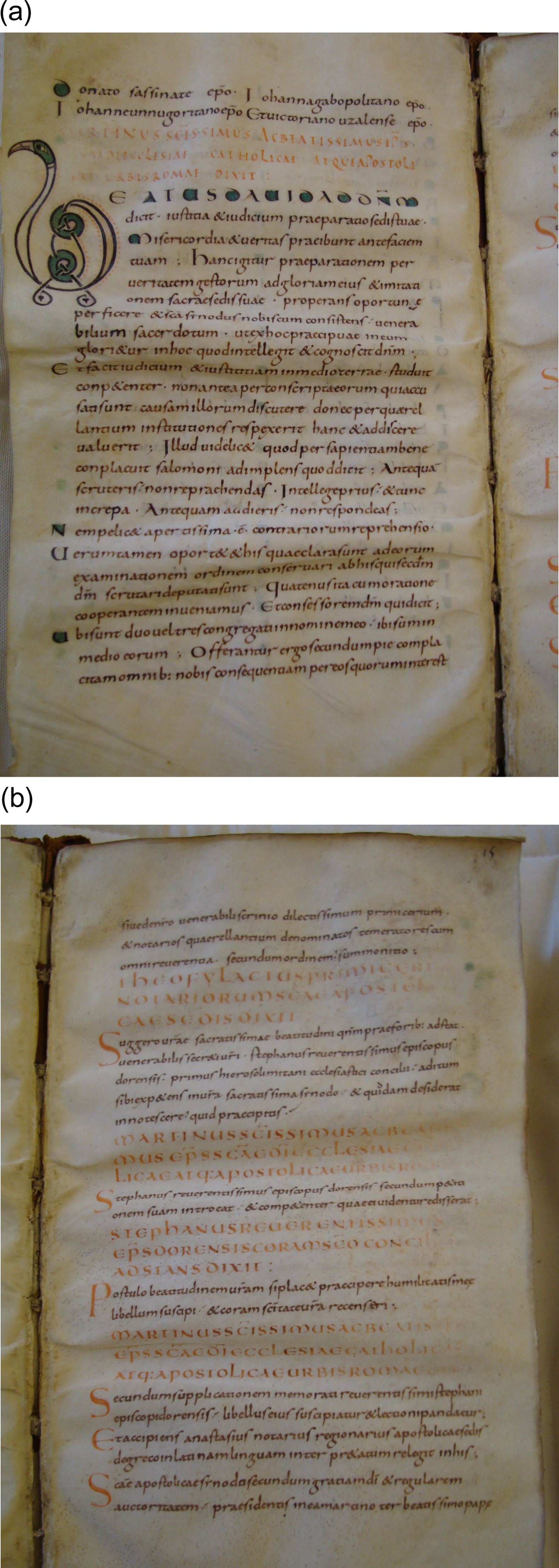

An extra factor in the case of Lateran 649 is that two versions of the proceedings are extant, one in Latin and one in Greek. The earliest manuscript of the Greek version (BAV, Vat. gr. 1455) is dated to the thirteenth century, where it is part of a miscellany of conciliar and theological material and early medieval papal letters, but the Greek version was originally sent to Bishop John of Philadelphia. The Latin version survives in a splendid early ninth-century Frankish codex, Laon, Bibliothèque Municipale Suzanne Martinet, MS 199, made at St Amand presumably from the very copy sent from Rome to Bishop Amandus of Maastricht in the seventh century (Fig. 9). These instances support the Liber pontificalis's statement (ed. Duchesne: 357) that Pope Martin ‘made copies and sent them through all the districts of east and west, broadcasting them by the hands of the orthodox faithful’. The Laon manuscript includes the text of the encyclical Martin wrote to accompany the Acta, as well as the letter to Amandus saying he has sent a copy of the entire Acta on volumina (the word usually used for rolls): ‘we have therefore taken steps that together with our encyclical the volumina of the synodal acts should at once be dispatched to you’.Footnote 34 Martin also asks Amandus to present the Acta before a specially convened synod of Frankish bishops and to tell the Frankish King Sigibert III about it. In the ninth century, Milo of St Amand included the letter to Bishop Amandus from Pope Martin in his Vita of Amandus. Milo had clearly seen the original material sent by Martin, for he referred to the Acta as written on papyrus sheets (in papireis schedis) (eds Krusch and Levison: 452).

Fig. 9. Ville de Laon, Bibliothèque Municipale Suzanne Martinet MS 199, fols 3v–4r with the end of the list of delegates and beginning of the Acta text. The codex is written in St Amand script of the first quarter of the ninth century and contains the Acta of the Lateran Council (649) and letters from Pope Martin I (d.655) to Amandus, Bishop of Maastricht (d.679 × 684). Reproduced with the kind permission of Sophie Etienne-Charles, Maire-Adjointe en charge de la culture de la ville de Laon.

The possibility that many more books from Rome were originally on papyrus, so much more vulnerable a writing material, is something I have discussed more fully in another context (McKitterick Reference McKitterick2020a: 176–8; Reference McKitterick, Herbers and Simprl2020b), but it is also relevant to any discussion of why so few books from the seventh and eighth centuries that might once have been in the papal library have survived. The use of papyrus in the papal chancery until the eleventh century is well attested, but papyrus as a writing material was not confined to charters and letters. Other conciliar acta, as shown in the famous fragment of the Council of Constantinople 680/1 discussed by Giuseppe De Gregorio and Otto Kresten (Reference De Gregorio, Kresten, Pani and Scalon2009), could have been recorded and distributed on papyrus. Papyrus books could be in the form of rolls or codices, but very few papyrus codices from Francia or Italy and dated to the sixth century or later are extant. Some examples are the Avitus codex now in Paris, BnF lat. 8913+ 8914, the fragments of biblical and legal texts in Paris, BnF lat. 12475, Isidore's Synonyma in St Gallen (Stiftsbibliothek csg 226), Josephus in Milan (Biblioteca Ambrosiana Cimelio MS 1) and the copy of Augustine discussed by Dario Internullo (Reference Internullo2019) (Paris, BnF lat. 11641) from the early eighth century.Footnote 35 These are all remnants of once substantial books. Their current fragmentary state is a stark reminder of their fragility. Internullo (Reference Internullo2019), moreover, has recently charted a far wider use of papyrus for documents beyond the papal chancery in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. He has stressed how many of our current early medieval documents may well have been copied from papyrus exemplars, and argued persuasively that the apparent change to parchment in the course of the eighth century had as much to do with archival practice and the imperatives of archival memory as with the economic context and sources of papyrus supply. Charlemagne's commissioning of a durable parchment copy of the papal letters on papyrus sheets received by the Frankish kings, referred to at the beginning of this paper, is an instance of this.

The proceedings of the Lateran Council of 649 were conducted in Latin, but the text's editor Riedinger (Reference Riedinger1998) argued that the Latin version sent to Francia in the seventh century from Rome was a translation of an original Greek text. His argument has of course raised the question about the status of the speeches put in the mouths of Martin and all the Italian bishops. As Richard Price has suggested, we should not think of the Acta as verbatim reports, but as a blend of prepared speeches delivered and then revised for the text that was circulated. The speeches present sophisticated theological exposition of the points in dispute. Extracts from both heretical and orthodox texts were read out at the sessions. Pope Martin himself had substantial interventions attributed to him.Footnote 36

Certainly, documents, relevant letters and florilegia had to be prepared and assembled beforehand, as at every council, and the chapters and canons with which the synod sessions concluded could also have been prepared in advance (Graumann, Reference Graumann2021). The lengthy commentaries on theological points undoubtedly suggest advance preparation, much as one prepares conference papers in advance. But as at any meeting, topics or questions could be raised or unexpected interventions occur. During the second session, for example, a request was made for the letter from Paul, patriarch of Constantinople, to be read and it had to be fetched and read out in Latin translation. The Acta naturally enough represent an edited account of proceedings, for we see the authoritative texts prepared for dissemination west and east. In other words, whether or not the Acta represent the actual script of the synod as distinct from a text padded out subsequently for western and eastern readers, with the relevant Greek texts in Latin and the Latin texts in Greek, does not detract from the significance of the document's reliance on the Lateran's resources.

The five sessions of the synod took place on 5, 8, 17, 19 and 31 October. The length of interval between sessions 2 and 3, and 4 and 5 was possibly needed to prepare the heretics’ statements and refutations and to assemble the florilegia. The proceedings were orchestrated by Theophylact, the primicerius notariorum or the head of the papal administration, with the assistance of four other regional notaries: Exsuperius, Anastasius, Paschal and Theodore. Time and time again in the Latin Acta, Pope Martin is recorded as reporting that the text on a particular issue is in ‘our sacred archives’ and it is then produced (Fig. 10). Theophylact, for his part, when presenting a text often announced that he had brought it from the sacred scrinium (he uses the word bibliotheca on one occasion). The regional notaries take it in turns to read out the various texts that are produced, especially in session 2, translating if necessary from Greek to Latin. The texts are all specified by author and title.

Fig. 10. Laon, Bibliothèque Municipale Suzanne Martinet MS 199, the opening fols 14v (this page) and 15r (opposite page) with an example of the record of the orchestration of speakers. Reproduced with the kind permission of Sophie Etienne-Charles, Maire-Adjointe en charge de la culture de la ville de Laon.

This seems to be very strong evidence of a reference collection close to hand. It was from this same collection that the florilegium of excerpts from different authors deployed in session 5 was compiled, in which two already existing florilegia by Maximus the Confessor and Sophronius of Jerusalem were included, in order to affirm that Christ had two wills and two operations (Alexakis, Reference Alexakis1996, Reference Alexakis2013; Price, Reference Price, Price, Booth and Cubitt2014: 286–96). When all the texts referred to and cited are added together, it amounts to a substantial reference collection of biblical, patristic, conciliar and exegetical texts. It cannot be proven that all these Greek and Latin texts were together in one single library, but the Acta account makes it sound as if these were indeed in the archivum, scrinium and bibliotheca of the Lateran. In comparison with earlier councils, moreover, the scale, range and the explicit recourse to reference material other than the contemporary documents prepared for the discussions recorded in the Lateran 649 Acta, quite apart from the proximity of the material brought to the sessions, are striking.Footnote 37

The preparations for the synod and the process described during the Acta are as important as the constant reference to particular texts. First of all, there is the work of writing letters, preparing the texts, extracts and florilegia of supporting statements for discussion, and copying out the Acta in both Latin and Greek for dissemination after the synod. We have to admire the very swift composition of the redacted texts of the Latin and Greek Acta after the event, and should not underestimate the skill of the notaries. It is a very considerable body of material. All the invitations to attend are one example: 106 bishops actually attended, so how many more letters of invitation were written and sent by the papal administration in Rome? Most of the bishops were from the Italian sees in the suburbicarian region as well as bishops from northeast Italy (e.g. Maximus of Aquileia, the representatives of Maurus of Ravenna), Sardinia (Deusdedit of Cagliari) and Corsica, though only one from Sicily (Catania and Syracuse were not represented). The celebrated theologian Maximus the Confessor, a refugee in Rome, attended with a contingent of monks from a number of ‘Greek-speaking’ monasteries in Rome (Sansterre, Reference Sansterre1983), but others elsewhere, in Palestine, Cyprus and North Africa, sent statements. We have no idea what or how accommodation was arranged for the visitors, but it was rare for a bishop or other delegate to travel without a companion or two: Maurus of Ravenna, for example, was represented by Maurus of Cesena and the priest Deusdedit of Ravenna.

The Latin version of the 649 Acta in the Laon manuscript, furthermore, that is, the Acta and Martin's encyclical summarizing the conclusions, plus Martin's letter to Amandus, occupy the entire codex of 137 leaves written in Caroline minuscule in a small folio format. In the thirteenth-century Greek manuscript in a small Greek minuscule, the Acta occupy 100 folios. We rarely have any direct equivalents offered of the same text in both papyrus rolls and codices, but one is Pope Gregory I's description of the composition of the Moralia in Iob in a letter to Leander of Seville, which he said filled 36 rolls or six codices.Footnote 38 The sheer quantity of books, collections of papal letters, collections of other conciliar proceedings, and florilegia referred to in the course of the synod, therefore, appears to be a striking witness to the use and contents of the papal archive and scrinium (Leclercq, Reference Leclercq1925: cols 871–3 reproducing De Rossi's list from 1866).

4. LATIN AND GREEK

The bilingual nature of the proceedings with the recourse to Latin and Greek and the Latin translations of Greek texts read out are a striking confirmation of the dominance of both Latin and Greek as the principal languages of formal communication in the notably cosmopolitan and multilingual city of Rome in the early Middle Ages. We are in a far stronger position to understand the presence and activity of Greek-speaking officials, immigrants and political and religious refugees (many from Palestine and Syria), often into the second and third generation, as a result of the classic study by Jean-Marie Sansterre (Reference Sansterre1983) on Greek monasteries in Rome, and the more recent work of Clemens Gantner (Reference Gantner2014), Maya Maskarinec (Reference Maskarinec2018), Philipp Winterhager (Reference Winterhager2020), Vera von Falkenhausen (Reference Falkenhausen and Consentino2021) and many others (Agati, Reference Agati1994). All these scholars have drawn attention to the cultivation of particular eastern saints’ cults, the introduction of elements of eastern liturgical observance, and the creation of new texts, especially saints’ lives and Passiones, as well as Greek translations of existing Latin texts in Rome, for which there was a Greek-reading audience.

Zacharias's translation of the Dialogues of Pope Gregory I that I mentioned above is a case in point, but of course the painted inscriptions in Greek in the church of Santa Maria Antiqua which Gordon Rushforth (Reference Rushforth1902) transcribed and identified more than a century ago need to be understood in this wider context. So do bilingual texts still extant, from the sixth-century Oxford Bodleian Library Laud gr. 35 (Lai, Reference Lai2011, Reference Lai2017), and the Latin and bilingual Latin and Greek glossaries from the eighth and the ninth centuries, though these still need further work.Footnote 39 Here one could also recall Pope Paul I's gift of Greek books to Pippin III, which Gastgeber (Reference Gastgeber, Pohl and Hartl2018) has identified as standard school texts for consolidating a knowledge of Greek, and which suggest attention being paid to the continuing needs of diplomatic and cultural exchange beyond Rome (McKitterick et al., Reference McKitterick, van Espelo, Pollard and Price2021: 246). A number of bilingual individuals as well as communities of Greek-speakers have been identified, notably within the Lateran and among those holding the papal office itself. The Liber pontificalis itself draws attention to the family origins of the popes, but it also makes clear how many of them had been trained in Rome, if not in the Lateran household itself (McKitterick Reference McKitterick2020a: 39–41; Reference McKitterick and Prudlo2023). Philipp Winterhager (Reference Winterhager2020), moreover, has not only emphasized the cultivation of a special style of writing Latin in the Roman scrinium; he has also made a cogent case for crediting the production of the Lateran Synod's texts to Lateran officials who were competent in both Latin and Greek, rather than to a notional group of Greek or Greek-speaking monks elsewhere in Rome.

5. CONCLUSION: THE FUNCTION OF THE PAPAL LIBRARY

This paper started with a well-established body of manuscript evidence in order to reflect on the light it might shed on the production of books in Rome from the sixth to the ninth centuries. I then turned to the papal resources indicated by the proceedings of the Lateran Council of 649 and their implications, not least for the Latin- and Greek-speaking communities in the cosmopolitan and multilingual city of Rome in the seventh and eighth centuries. These resources continued to be drawn on, as is evident in papal letters during the eighth century (McKitterick et al., Reference McKitterick, van Espelo, Pollard and Price2021). The popes appear to have been presiding over a very substantial library that remained a crucial resource throughout the ninth century as well.

The evidence on which I have concentrated here is weighted towards biblical, liturgical, patristic, theological, doctrinal and exegetical texts. Hints such as Lupus of Ferrières's letter to Pope Benedict III (Ep. 100, ed. Levillain: II, 122) requesting copies of Quintilian and Donatus, however, as many before me have commented, suggest that the library may have included secular and ancient texts as well. One famous late fourth- or early fifth-century uncial remnant of Livy survives in BAV, Vat. lat. 10696. It was used as a wrapper for relics from the Holy Land, in the seventh or early eighth century, and placed in the chapel of San Lorenzo in the Lateran in the time of Pope Leo III (CLA I, 57). The journeys to Rome I mentioned at the outset as well as Lupus's request seem to indicate knowledge of what might be available in Rome. They raise the question of whether there was once some kind of catalogue of the books in the papal library in circulation, similar to the ninth-century compilations that survive from Lorsch, Reichenau or St Gallen (Lehmann, Reference Lehmann1918; McKitterick, Reference McKitterick1989: 169–210; Häse, Reference Häse2002).

There is a considerable body of evidence pointing towards book production in a number of centres in Rome. The papal writing office may have been one such production centre (Niskanen, Reference Niskanen2021). The Lateran collection of books, whether of texts actually produced in the papal writing office, in other centres in Rome, or elsewhere, appears to have been regarded as a source of texts. In this respect the regret Pope Martin expressed in his letter to Amandus is curious, to say the least. Martin had told Amandus that a text could not be copied in Rome by Amandus's courier because the papal library was empty or ‘reduced to nothing’ (the phrase used is exinaniti sunt).Footnote 40 There is a coincidental echo about the papal library in the so-called vision of Taio of Saragossa on his visit to Rome c. 650, an account of which was preserved in the Mozarabic Chronicle of 754. The text refers to the great multitude of books in the archives of the Roman Church and the consequent difficulty of obtaining copies of texts from the papal library, or even being able to find them. In his vision, Taio was helped by Saints Peter and Paul and Pope Gregory I himself, who showed him where the works of Gregory were hidden, but were unable to be precise about the location of the works of Augustine.Footnote 41

Such stories prompt further questions. Were too many people borrowing books in order to make copies? Was there an organized system of provision of exemplars? Were texts usually made available to visitors or to scribes to copy? Was any control exerted over the copying process, such that the pope himself was kept informed? Were copies sold or given to visitors? Was there a system for formal distributions at particular moments? Were visitors supplied with authorized copies of particular texts, much as Martin sent the authoritative version of Lateran 649 to Amandus? Did visitors make their own copies from versions available in the papal archive or bibliotheca? Did they pay for them, acquire copies of books in Rome from other sources, or did they otherwise supply their own writing materials as well as scribes?

One possible book made by the scribes in a Frankish visitor's entourage while in Rome is BAV, reg. lat. 1040, a copy of the Latin text of the Sixth Oecumenical Council (680–1). The scribes wrote in the distinctive Caroline minuscule associated with St Amand and Salzburg at the turn of the eighth century. Bernhard Bischoff (Reference Bischoff1980: 103) suggested that the production of this codex could be linked with the visit to Rome in 787 by Arn, bishop of Salzburg and abbot of the north Frankish monastery of St Amand.Footnote 42 Copied on a quire-by-quire basis, it also contains corrections in a Roman curial hand of the late eighth century, that is, apparently when the codex was still in Rome (Rabikausas, Reference Rabikausas1958: 61).

Of course, other institutions in Rome at the time can be surmised to have possessed books, and I daresay private individuals did as well, if we allow ourselves to imagine parallels between the wealthier members of Roman society in the early Middle Ages and similar individuals elsewhere (McKitterick, Reference McKitterick1989: 169–96; Wormald and Nelson, Reference Wormald and Nelson2007). My discussions of the few extant books that are judged to have been produced in Rome, references to the papal scrinium and bibliotheca, their possible location as well as the implications of the case study of the Lateran Council of 649, all indicate that the papal library can be thought of in pragmatic terms. That is, it remains legitimate to ask where it was, what was in it, and even what practical utility it served in the period between the fifth and the ninth centuries.

A further consideration, however, is the symbolic dimension of the papal library. The popes sought to emulate and eventually replace the Roman emperors. This manifests itself in their rhetoric in their many letters and treatises, in their physical impact on the city of Rome and in the ideological claims they make as the rock on which Christ built his church. The Liber pontificalis, a narrative history of the bishops of Rome, was deliberately presented in a similar format to the serial biographies of Roman emperors by Suetonius and the authors of the Augustan History (McKitterick, Reference McKitterick2020a: 9–11).

The imperial libraries of the ancient world had been opulent and dramatic symbols of wealth, power and prestige, as well as storehouses of contemporary and older learning and literary masterpieces, with an extra element at times of being a repository of approved authors (Neudecker, Reference Neudecker, König, Oikonomopoulou and Woolf2013). If such a display is translated into papal terms, the papal library maintains a comparable status of wealth, power and prestige, but it is also a repository for orthodox and authoritative texts on all aspects of the Christian religion. Imperial libraries have been described as archives in sacred places which offered a religious protection for the words (Purcell, Reference Purcell, Boardman, Griffin and Murray1988). If such a description can be applied to the papal library it would be no accident that the library might have been in such close proximity to the sancta sanctorum and the oratory of the Roman martyr St Laurence, as well as the Lateran patriarchum and basilica of the Saviour.

Sacred place, knowledge, records, religious protection and power were all combined in Roman ways of thinking about libraries as much in the early Middle Ages as they had been in the ancient world. The Lateran Synod of 649, for all its misrepresentation of the eastern position on Christ's person and natures, presents, in its concentrated assemblage of both authoritatively orthodox and supposedly heretical views, an assertion of the pope's role as guarantor of orthodoxy and custodian of the Christian faith which was underpinned by the resources of the papal library. In the heart of Rome, the papal library therefore became more than a collection of useful books; it was a representation of authority and contained the texts that embodied the textual community of the Christian Church throughout the early Middle Ages.

Acknowledgements

I should like to thank the former and current directors of the British School at Rome, Stephen Milner and Abigail Brundin, for their kind invitation to deliver the first Gordon Rushforth lecture on medieval Rome at the BSR in Rome in November 2021 on which this paper is based. I am grateful also to my audience in Rome as well as that at a subsequent presentation at the Freie Universität Berlin, especially Stefan Esders, and to the two anonymous assessors for the PBSR for their comments and suggestions. I am particularly grateful to Dario Internullo for discussing the use of papyrus in the early Middle Ages with me. Special thanks are due to John Osborne for his generosity and suggestions, and for providing me with the illustration of the ‘Augustine/Jerome’ portrait; to Hendrik Dey for sending me an image of Manfred Luchterhandt's reconstruction of the Lateran complex in the early Middle Ages; and to Manfred Luchterhandt for his permission to use it. For permission to reproduce the folios from Laon Bibliothèque Municipale Suzanne Martinet MS 199, I am indebted to Sophie Etienne-Charles, Maire-Adjointe en charge de la culture de la ville de Laon. My thanks also are due to Dr Cornel Dora, Stiftsbibliothekar, for permission to reproduce the detail from the St Gall Plan (Stiftsbibliothek St Gallen csg 1092), and to Dr Marcus Vaillant of the Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Düsseldorf for permission to reproduce Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Düsseldorf Hs E.1.