Introduction

Over recent years, medical advancement has made various life-sustaining and life-prolonging interventions possible in the course of disease. People nowadays often have more health and social care choices when facing health challenges. The decision-making process always embeds balancing burdens and benefits with uncertain facts and more with the personal values of patients or their families. This may pose a significant challenge to the individual and family during an emotionally stressful period if it has never been discussed previously (Schubart et al. Reference Schubart, Levi and Dellasega2014), and advance care planning (hereafter ACP) has received increasing attention since the 1990s (Stoppelenburg et al. Reference Stoppelenburg, Rietjens and van der Heide2014). ACP is an iterative communication process in which people discuss their future end-of-life care and treatment plan with their family and healthcare providers. ACP ensures that even if the patient loses mental capacity at that time, the care provided is consistent with their personal values and preferences (Sudore et al. Reference Sudore, Lum and You2017). However, despite ACP’s medical, legal, and pragmatic utility and benefits, uptake remains low (Frechman et al. Reference Frechman, Dietrich and Walden2020).

Several systematic reviews of factors related to ACP have been published in recent years. However, they tend to focus on specific groups, such as people with intellectual disabilities (Voss et al. Reference Voss, Vogel and Wagemans2017), pediatric patients (Brunetta et al. Reference Brunetta, Fahner and Legemaat2022), adult glioblastoma patients (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Colon and Aslakson2021), people with dementia (Tilburgs et al. Reference Tilburgs, Vernooij-Dassen and Koopmans2018), disadvantaged adults (Brean et al. Reference Brean, Recoche and William2023), and underrepresented racial and ethnic groups (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Luth and Lin2021). Some are restricted to a specific setting, such as nursing homes (Gilissen et al. Reference Gilissen, Pivodic and Smets2017; Ng et al. Reference Ng, Takemura and Xu2022) or general practice clinics (Risk et al. Reference Risk, Mohammadi and Rhee2019; Tilburgs et al. Reference Tilburgs, Vernooij-Dassen and Koopmans2018). The growing understanding of ACP practices among different groups in different settings evidences the significance of the topic and provides descriptive knowledge of the activity. There are also a few systematic reviews and meta-analyses on ACP interventions, which address the efficacy of using conversation guides (Fahner et al. Reference Fahner, Beunders and van der Heide2019) or generic ACP intervention (Malhotra et al. Reference Malhotra, Huynh and Shafiq2023). As ACP is a complex intervention, its evaluation should capture the underlying mechanism of changes or underpinning program theory and recognize its context (Skivington et al. Reference Skivington, Matthews and Simpson2021). Studies identifying impeding and facilitating factors in ACP are needed to postulate the mechanisms of change and guide the development of evidence-based or evidence-informed practice. Schichtel and colleagues (Reference Schichtel, Wee and Perera2020) published a systematic review of clinician factors among heart failure ACPs. Batchelor and colleagues (Reference Batchelor, Hwang and Haralamhous2019) and Risk and colleagues (Reference Risk, Mohammadi and Rhee2019) reviewed studies in Australia and identified factors of ACP in aged care settings and general practice clinics, respectively. Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Martina and van der Heide2023) reviewed the role of acculturation in the process of ACP among Chinese immigrants. One systematic review among the general population on the factors is limited to contextual factors of ACP only (Lovell and Yates Reference Lovell and Yates2014). There is no comprehensive view of impeding and facilitating factors for ACP discussions among a wider range of users. The process and outcome of ACP discussion can be affected by both non-modifiable and modifiable factors. The non-modifiable factors help to identify who to target for ACP and whereas, the modifiable factors provide direction on how and what can be improved to achieve ACP. This review aims to inform professionals in healthcare settings about the modifiable factors affecting ACP practice.

Additionally, Lovell and Yates (Reference Lovell and Yates2014) and McDermott and Selman (Reference McDermott and Selman2018) suggested that ethnicity and culture have a role in affecting ACPs. Most published systematic reviews relate to studies reported in English. This review also expands its sources to include papers published in Chinese to increase insights for those located in communities with a significant Chinese population.

Methods

This review followed the PRISMA guidelines and was registered with PROSPERO (reference no. CRD42021229829).

Eligibility criteria

This review included only primary research reporting on ACP or ACP discussion with patients suffering from progressive illness published either in English or Chinese in peer-reviewed journals. “Factors” refers to the modifiable impeding or facilitating factors related to ACP from the perspective of the patient, their family or healthcare professional. “Health Care Settings” include both ambulatory care and in-patient care provided in hospital or community health clinics.

Information sources and search

Five English-language databases (ProQuest, PubMed, CINAHL Plus, Scopus, and Medline) and two Chinese-language databases (CNKI and NCL) were searched for studies meeting the inclusion criteria published from inception to November 2022. Table 1 outlines the search teams.

Table 1. Database search strategy

Screening and selection of studies

All publications identified by the search engines were exported using Endnote software, and duplicate articles were removed by the first author (MS). Initial abstract screening was performed by 4 reviewers independently (MS, RW, AC, SKY); 1 reviewer (MS) screened all articles and the other 3 reviewers (AC, SKY, RW) each screened one-third of the abstracts. The results were compared, and discrepancies in selection were resolved by discussion in 2 online meetings. Full-text screening of 45 included articles was subsequently undertaken by 3 reviewers (MS, RW, AC). MS reviewed all full-texts, and RW and AC each reviewed half. Any discrepancies were discussed between the reviewers, and consensus was achieved following 2 online meetings within 2 weeks.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Data were extracted by 2 reviewers (MS, RW) using a standardized data extraction form to provide consistency, reduce bias, and increase the validity and reliability of the data extraction (Cumpston et al. Reference Cumpston, McKenzie and Welch2022). The results were organized and sent to reviewers for verification. Methodological quality was assessed using the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT), which can accommodate qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies and has good validity and reliability (Pace et al. Reference Pace, Pluye and Bartlett2012). In general, the 3 authors (MS, AC, RW) agreed on the assessment of methodology quality. Of the 45 included articles, the 3 authors agreed that 33 (73.3%) were good, with a rating of 4 or 5 out of 5, and 12 (26.7%) were fair, with a rating of 2 or 3 out of 5.

Data analysis and synthesis

Data analysis was informed by the Framework Method involving thematic analysis (Gale et al. Reference Gale, Heath and Cameron2013). The first author (MS) performed the coding stages with the articles based on the standardized extraction form. The themes were identified and categorized into an analytical framework worksheet with statistical or qualitative information from the studies. An expert panel comprising 2 academic professors, a postdoctoral fellow, and 2 researchers critically reviewed the categorization. The thematic categories were further refined to derive a final set of codes to interpret the results. This study used a descriptive approach to report the findings, and given the heterogeneity of the included studies, it was not feasible to pool results or use meta-analytical approaches.

Results

Study selection

The selection process is illustrated in Figure 1 on the PRISMA diagram. Forty-five studies, 32 in English and 13 in Chinese, were included and proceeded to data extraction as listed in Table 2a and 2b.

Table 2. (a) Summary of the included English articles (n = 32). (b) Summary of the included Chinese articles (n = 13)

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram: barriers and facilitators of advance care planning in healthcare settings.

Study characteristics

Table 3 summarizes the study design, subjects, disease types, and analytical lens of each included study. Twenty-four (53.4%) studies used quantitative methodology (cross-sectional survey or retrospective data mining), 15 studies (33.3%) used qualitative methodologies (e.g., interviews or focus groups), and the remaining 6 studies (13.3%) used mixed methods. No study utilized a randomized controlled trial.

Table 3. Characteristics of the included studies

Around one-third of the studies were conducted in North America (i.e., the United States and Canada); another third were conducted in Mainland China, and the remaining studies were conducted in other regions, such as Europe and elsewhere in Asia. Patients’ illness spectrum covered both cancer and non-cancerous diseases.

Regarding the study subjects, 62% studied a single subject group. Of the studies that involved more than 1 subject group, only 2 (4%) employed a dyadic lens in the research; analysis and reporting in the remaining studies focusing on an individual group’s perspective.

Factors influencing ACP discussion

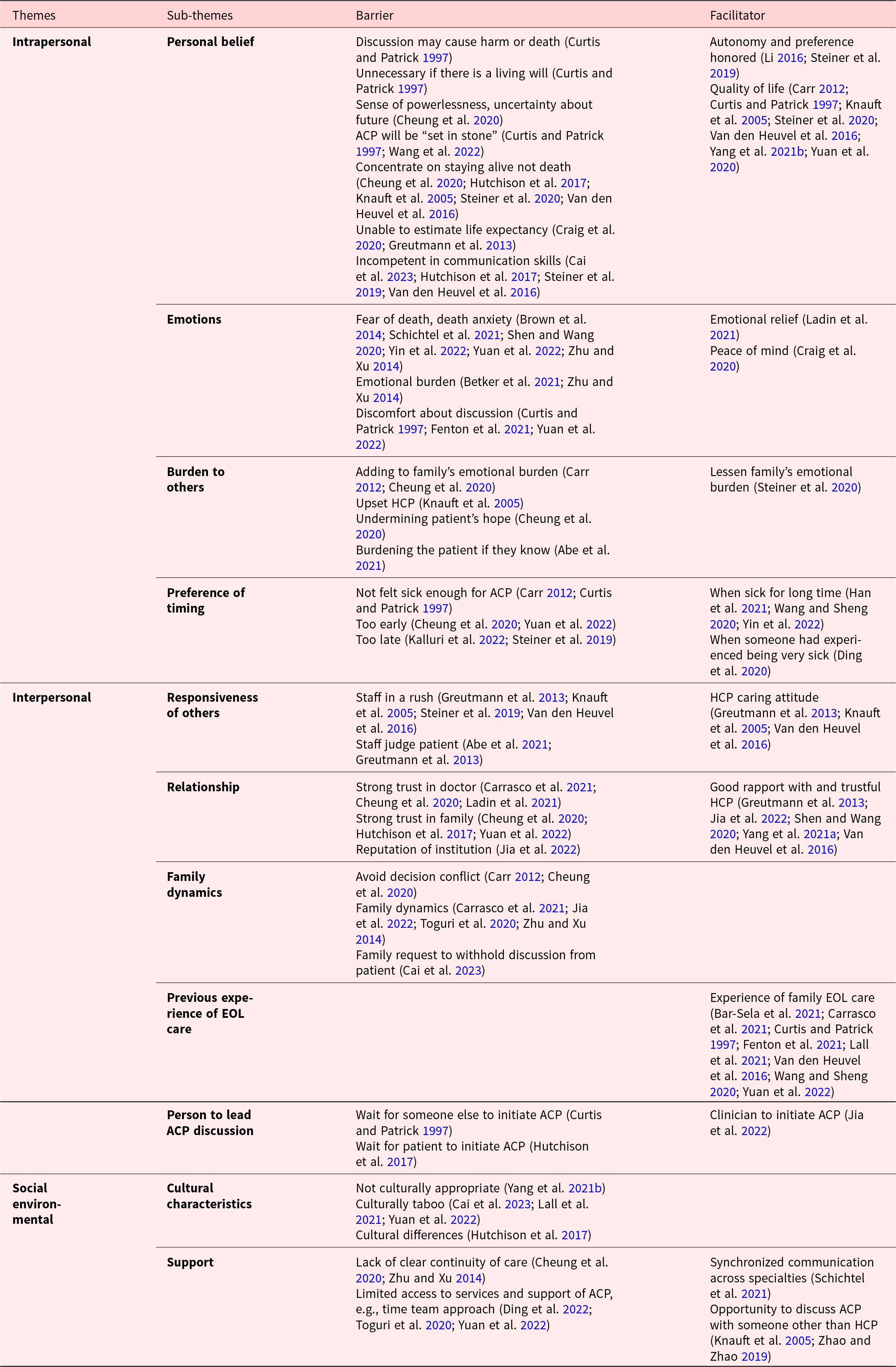

The qualitative and quantitative findings were summarized into 3 thematic categories: (1) intrapersonal, (2) interpersonal, and (3) socio-environmental, and further differentiated in terms of the factors’ orientation toward a particular participant group or all groups. Table 4 summarizes the factors and the direction of the force as barriers or facilitators.

Table 4. Summary of themes and direction of the force of the included studies

Intrapersonal factors

Personal belief

Barriers reported by patients included the personal belief that the consequence of ACP discussion would be harmful or cause death (Curtis and Patrick Reference Curtis and Patrick1997). Patients and family members both referred to the beliefs that they are powerless in facing death and that ACP discussion was unethical and uncertain on health (Cheung et al. Reference Cheung, Ip and Chan2020; Greutmann et al. Reference Greutmann, Tobler and Colman2013; Knauft et al. Reference Knauft, Nielsen and Engelberg2005; Li and Li Reference Q and X2016) and that concentrating on staying alive was a preferable response (Cheung et al. Reference Cheung, Ip and Chan2020; Greutmann et al. Reference Greutmann, Tobler and Colman2013; Knauft et al. Reference Knauft, Nielsen and Engelberg2005; Steiner et al. Reference Steiner, Stout and Soine2019; Van den Heuvel et al. Reference Van den Heuvel, Hoving and Schols2016). Physicians’ beliefs impeding their involvement in ACP included affording it lower priority and considering it to be time-consuming (Hutchison et al. Reference Hutchison, Raffin-Bouchal and Syme2017; Van den Heuvel et al. Reference Van den Heuvel, Hoving and Schols2016), the role of a physician is to treat the illness (Curtis and Patrick Reference Curtis and Patrick1997; Ladin et al. Reference Ladin, Neckermann and D’Arcangelo2021) and that end-of-life care discussion was best done by other experts (Cai et al. Reference Cai, Wang and Wang2023; Craig et al. Reference Craig, Ray and Harvey2020; Greutmann et al. Reference Greutmann, Tobler and Colman2013; Hutchison et al. Reference Hutchison, Raffin-Bouchal and Syme2017; Steiner et al. Reference Steiner, Dhami and Brown2020; Van den Heuvel et al. Reference Van den Heuvel, Hoving and Schols2016).

Patients’ beliefs in self-autonomy (Li and Li Reference Q and X2016; Steiner et al. Reference Steiner, Dhami and Brown2020; Van den Heuvel et al. Reference Van den Heuvel, Hoving and Schols2016) or believing that ACP discussion would result in a better quality of life for them (Carr Reference Carr2012; Curtis and Patrick Reference Curtis and Patrick1997; Greutmann et al. Reference Greutmann, Tobler and Colman2013; Knauft et al. Reference Knauft, Nielsen and Engelberg2005; Steiner et al. Reference Steiner, Stout and Soine2019; Van den Heuvel et al. Reference Van den Heuvel, Hoving and Schols2016; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Hou and Chen2021b; Yuan and Liu Reference Yuan and Liu2020) have positive influence on ACP discussion. Most studies reporting this focused on Western populations.

Emotions

Patient, family, and physician groups reported the emotions induced by talking about death and dying. A negative attitude toward death is correlated to less acceptance of ACP discussion among Chinese patients and families (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Shen and Ramondetta2014; Schichtel et al. Reference Schichtel, MacArtney and Wee2021; Shen and Yang Reference Shen and Yang2020; Yin Reference Yin, Shu and Wang2022; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Zhao and Wang2022; Zhu and Xu Reference Zhu and Xu2014). Feeling a psychological burden and discomfort was reported by patients in 5 studies (Betker et al. Reference Betker, Nagelschmidt and Leppin2021; Curtis and Patrick Reference Curtis and Patrick1997; Fenton et al. Reference Fenton, Fletcher and Bowles2021; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Zhao and Wang2022; Zhu and Xu Reference Zhu and Xu2014), and the topic was not welcoming. Emotional burden can also be a barrier for healthcare professionals. Physicians referred to their fear of facing a patient’s death and not being ready to let the patient die (Cheung et al. Reference Cheung, Ip and Chan2020; Schichtel et al. Reference Schichtel, MacArtney and Wee2021). Emotional distress would encourage avoiding the discussion, and when other parties feel the same, ACP would never be initiated.

Burden to others

Patients avoided ACP because of concern that such discussion would burden their significant other(s) (Carr Reference Carr2012; Cheung et al. Reference Cheung, Ip and Chan2020). Patients’ significant others did not include family members only. In 2 studies, patients felt that discussing their end-of-life care would upset their physician (Curtis and Patrick Reference Curtis and Patrick1997; Knauft et al. Reference Knauft, Nielsen and Engelberg2005). Families sometimes requested keeping such discussions from the patient, and physicians worried that discussing ACP would undermine the patient’s hope. Intent to protect became a hurdle for patients’ participation in ACP discussions (Abe et al. Reference Abe, Kobayashi and Kohno2021; Cheung et al. Reference Cheung, Ip and Chan2020). While some studies reported intent to avoid emotionally burdening others as a barrier, other studies found participants had different views, perceiving that advance discussion would lessen other parties’ emotional burden, especially in end-of-life decision-making (Steiner et al. Reference Steiner, Stout and Soine2019).

Preference of timing

Inappropriate timing was identified as a barrier in ACP discussion; however, perceptions of appropriateness differed among participant groups. Some studies reported that patients thought “too early” and “not sick enough” were indictors of inappropriateness (Carr Reference Carr2012; Cheung et al. Reference Cheung, Ip and Chan2020; Curtis and Patrick Reference Curtis and Patrick1997; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Zhao and Wang2022). However, “too late for discussion” was also presented as a barrier, rendering ACP unrealistic (Kalluri et al. Reference Kalluri, Orenstein and Archibald2022; Steiner et al. Reference Steiner, Dhami and Brown2020). The deliberation of “not too early” was also differed. Some studies elaborated by the person had experienced a very sick time, had but some studies referred to a long duration of sickness or occurrence of significant illness burden (Ding et al. Reference Ding, Hu and Ma2020; Han et al. Reference Han, Li and Gan2021; Hutchison et al. Reference Hutchison, Raffin-Bouchal and Syme2017; Wang and Sheng Reference Wang and Sheng2020; Zhao and Zhao Reference Zhao and Zhao2019).

Interpersonal factors

Responsiveness of others

Almost all studies reported physicians’ response as a factor determining patients’ participation in ACP. Besides skills and clinical knowledge, a physician’s attitude, such as empathic care, sensitivity to the patient’s cultural characteristics, and addressing their needs can facilitate patient participation (Greutmann et al. Reference Greutmann, Tobler and Colman2013; Knauft et al. Reference Knauft, Nielsen and Engelberg2005; Van den Heuvel et al. Reference Van den Heuvel, Hoving and Schols2016). Patients’ perceptions of the physician as in a rush and having no time for such discussion impeded their participation in ACP (Greutmann et al. Reference Greutmann, Tobler and Colman2013; Knauft et al. Reference Knauft, Nielsen and Engelberg2005; Steiner et al. Reference Steiner, Stout and Soine2019). In any event, physicians would not proceed if they judged the patient not suitable or not ready to discuss ACP (Abe et al. Reference Abe, Kobayashi and Kohno2021; Greutmann et al. Reference Greutmann, Tobler and Colman2013). The responses of patients and physicians mutually influenced each other in ACP discussions.

Relationship

A trustful relationship can be a facilitator or a barrier in ACP. Firm trust in the physician increased patients’ confidence to share their preference for end-of-life care (Greutmann et al. Reference Greutmann, Tobler and Colman2013; Jia et al. Reference Jia, Yeh and Lee2022; Shen and Yang Reference Shen and Yang2020; Van den Heuvel et al. Reference Van den Heuvel, Hoving and Schols2016; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Dionne-Odom and Foo2021a). Nevertheless, firm trust in the physician or family was also a barrier that lowered a patient’s incentive for ACP because they were confident that the other parties understood their wishes and were willing to place total trust and leave all decisions to them (Carrasco et al. Reference Carrasco, Koch and Machacek2021; Cheung et al. Reference Cheung, Ip and Chan2020; Hutchison et al. Reference Hutchison, Raffin-Bouchal and Syme2017; Ladin et al. Reference Ladin, Neckermann and D’Arcangelo2021; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Zhao and Wang2022).

Family dynamics

Physicians’ readiness to engage in ACP discussions was reduced when families experienced preexisting conflict as they felt they did not have either the skills or the time to manage difficult family dynamics. Patients avoided ACP discussion if they anticipated the discussion would arouse conflicts in the family (Carr Reference Carr2012; Carrasco et al. Reference Carrasco, Koch and Machacek2021; Cheung et al. Reference Cheung, Ip and Chan2020; Jia et al. Reference Jia, Yeh and Lee2022; Lall et al. Reference Lall, Dutta and Tan2021; Toguri et al. Reference Toguri, Grant-Nunn and Urquhart2020; Van den Heuvel et al. Reference Van den Heuvel, Hoving and Schols2016; Zhu and Xu Reference Zhu and Xu2014). Chinese physicians reported that their reluctance to initiate ACP was due to the fear of being misunderstood by the family for not making sufficient effort to treat the patient (Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Zhao and Wang2022).

Previous experience of end-of-life care

Eight studies reported that experiencing the death of someone close or providing end-of-life care for such a person positively influenced their perception of the value of ACP. Experience of a family member’s death with palliative care support, free from suffering, positively influenced their own ACP discussions (Bar-Sela et al. Reference Bar-Sela, Bagon and Mitnik2021; Carrasco et al. Reference Carrasco, Koch and Machacek2021; Curtis and Patrick Reference Curtis and Patrick1997; Fenton et al. Reference Fenton, Fletcher and Bowles2021; Lall et al. Reference Lall, Dutta and Tan2021; Van den Heuvel et al. Reference Van den Heuvel, Hoving and Schols2016; Wang and Sheng Reference Wang and Sheng2020; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Zhao and Wang2022; Zhao and Zhao Reference Zhao and Zhao2019).

Person to lead ACP discussion

The views on the person to lead ACP discussion varied and impeded the kickoff of ACP discussion. Physicians preferred the patient to initiate the discussion (Hutchison et al. Reference Hutchison, Raffin-Bouchal and Syme2017), while patients expected healthcare professionals to take the lead (Jia et al. Reference Jia, Yeh and Lee2022). Adopting a passive role and waiting for someone else to initiate ACP was one reason for the low uptake of ACP (Curtis and Patrick Reference Curtis and Patrick1997).

Socio-environmental factors

Cultural characteristics

Different cultural beliefs and practices were reported in 6 studies. Four of these were conducted in Asia and one study on a minority group. Some studies reported rejection of ACP discussion due to cultural taboos regarding talking about death (Cai et al. Reference Cai, Wang and Wang2023; Lall et al. Reference Lall, Dutta and Tan2021; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Zhao and Wang2022). Some studies also mentioned that the decision-making role of the family in the decision-making process was also different in different cultures (Hutchison et al. Reference Hutchison, Raffin-Bouchal and Syme2017; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Hou and Chen2021b). Lack of sensitivity to cultural characteristics is the barrier to ACP rather than cultural differences.

Support

Patients and families were reluctant to discuss ACP when subsequent continuity of care for the patient was uncertain, including not knowing where to get support (Cheung et al. Reference Cheung, Ip and Chan2020; Zhu and Xu Reference Zhu and Xu2014). Lack of communication between clinical departments also diminished patients’ readiness to discuss ACP (Schichtel et al. Reference Schichtel, MacArtney and Wee2021). Healthcare professionals reported that organizational support such as having protected time for discussion, training on skills and tools, and policies, a standardized protocol and documentation were helping factors (Ding et al. Reference Ding, Cook and Saunders2022; Ladin et al. Reference Ladin, Neckermann and D’Arcangelo2021; Simon et al. Reference Simon, Porterfield and Bouchal2015; Toguri et al. Reference Toguri, Grant-Nunn and Urquhart2020; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Zhao and Wang2022). Other than the infrastructural support from the healthcare system, topic-specific support, such as having someone in the social environment to accommodate dialogue about end-of-life care, can facilitate patients and families in preparing for ACP discussion (Dai and Zhang Reference Dai and Zhang2021; Knauft et al. Reference Knauft, Nielsen and Engelberg2005; Shen and Yang Reference Shen and Yang2020; Zhao and Zhao Reference Zhao and Zhao2019).

Discussion

The interweaving of systemic and dynamic factors

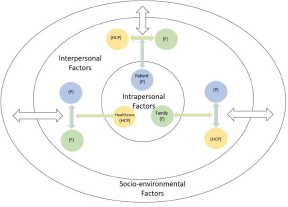

Factors elicited from the reviewed studies were not unidimensional but included intrapersonal, interpersonal, and socio-environmental level which reflected the interactive and dynamic characteristics of the different factors.

The intrapersonal factors identified in this study were more than matters about individuals but comprised the personal belief of self and others, one’s own emotions, and the perceived emotions of others. Moreover, personal beliefs or emotions toward ACP interacted with the external world and contributed to the outcomes of the interpersonal factors. In this study, the interpersonal factors of “trustful relationship” and “family dynamics” are examples of reciprocal influence resulting in bidirectional outcomes as facilitators or barriers to ACP. This bidirectional nature of interpersonal factors was consistently found in other studies (Rhee et al. Reference Rhee, Zwar and Kemp2013). The factor, relationship, can be an impeding or facilitating factor shaped by the context, the relationship, and the individual belief. The interaction process and direction are chaotic and messier than a linear model. There is a need for further exploration. The motive to protect oneself from the negative consequences of relationship disintegration may generate a perception of ACP as a risk. Conversely, the motive to enhance the relationship by actively handling disagreement and conflicts may welcome ACP as an opportunity. The direction and magnitude of “trust” and “burden” may be determined by the individual’s underlying motives.

Socio-environmental factors such as culture and social support are interweaved with intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. Discussing death and dying may still be taboo in some cultures; research indicates Asians tend to adopt culture-specific beliefs such as fatalism to cope with death (Yen Reference Yen2013). When the social environment discourages talking about death, the mystery of death and dying accelerate a person’s fear, and subsequently reconfirmed such discussion as burdensome both to the person and other people around them. The study suggested an interweaving relationship of the 3 categories of factors in considering ACP discussion as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Interweaving of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and socio-environmental factors.

The interweaving of factors among the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and socio-environmental dimension suggest ACP is a complex dynamic interplay within the person and in relation to others. However, the dynamic interplay among patients, family and healthcare professionals, and the core elements that drive their force toward or against ACP have not been explored. ACP is a communication process involving these 3 parties regarding the patient’s preferences of end-of-life care, which not only affects the patient’s quality of care but also has significant impacts on family and caring professionals. A deeper understanding of their interactions and impacts in ACP can not only help to formulate strategies to enhance ACP uptake but also provide a feasible channel for constructive participation to improve end-of-life care communication.

The missing piece of a triadic perspective

ACP is a communication process between at least 3 parties: the persons involved, their family members, and their healthcare professionals. Nevertheless, only 2 studies examined participants in patient and family dyads. All other studies were conducted through the lens of a single stakeholder group, resulting in an incomplete understanding of the phenomenon. Fletcher (Reference Fletcher, Miaskowski and Givern2012)suggests the dyadic-level concept between patient and caregiver on “communication,” “reciprocal influence,” and “caregiver-patient congruence” in facing the course of illness. Another study also found a correlation between patients’ and their partners’ distress, suggesting they reacted as an emotional system rather than as individuals (Kershaw et al. Reference Kershaw, Ellis and Yoon2015). Healthcare professionals are a core stakeholder group in ACP, particularly when ACP is discussed in healthcare settings. Understanding of the communication, reciprocal influence, and congruence needs to be triadic among patients, families, and healthcare professionals.

Universality and distinctiveness of factors between the Chinese societies and the West

One of the expected contributions of this review is to offer a more comprehensive view of the factors by including studies for Chinese, for a wider range of targets, and in different settings. Among the 45 studies, 16 of them researched on the Chinese population in different regions including Hong Kong, Taiwan, and mainland China.

Disregarding the study regions, appropriate time to initiate the ACP discussion is shared even with different perceptions on appropriateness. Emotional burdens on self and others were another shared challenge faced by the patient, the family, and healthcare professionals. Accessible emotional support pre- and post-ACP discussion is as important as the support during the discussion.

While a sense of autonomy and quality of life was the dominant focus of the intrapersonal factors in Western society, death belief, illness condition, and information about ACP had a more significant influence on participation in ACP in the Chinese communities. Culture, family, and social support were reported more often in the research on Chinese population. Although majority of the included Chinese studies are from China, the findings on the essential role of family and relationship are consistent with other literature reported (Martina et al. Reference Martina, Lin and Kristanti2021). In a collectivist Asian culture, sociocultural factors pose an important barrier; discussing end-of-life issues is considered taboo and against cultural values, such as filial piety (Ali et al. Reference Ali, Anthony and Lim2021).

Family is a linchpin in Chinese society, and harmonious relations are of paramount importance in making major decisions (Leung et al. Reference Leung, Brew and Zhang2011). Although some studies in this systematic review did include family members in studying the factors affecting ACP, they were researched as a patient proxy or supplemented the patient’s perspective rather than focusing on the interactions of family and other stakeholders in the initiation or discussion process.

Conclusion

This study draws a comprehensive picture of existing knowledge of the modifiable factors of ACP in healthcare settings for patients with a progressive illness. It has several implications for clinical practice and future research. First, it provided a systemic and dynamic lens on the modifiable factors affecting ACP discussion. Factors can be bidirectional and not absolutely a barrier or facilitator, and they are interweaving among intrapersonal, interpersonal, and socio-environmental dimensions. However, little was known about the interplay and warrant research on the dynamic interactions from a tripartite perspective. Second, apart from the universal factors affecting the uptake of ACP, more attention needs to be paid to the distinctive factors reflecting the population’s characteristics. Family concerns may be weighted more important than the individual in some cultures and the decision making may vary in different populations. Being sensitive to the cultural issues and honor the uniqueness of the population characteristics would enable continuous communication. For instance, some societies address death and dying openly while it remains a taboo in the others. Pre-ACP preparation is necessary to explore the concerns and needs in the context, healthcare professionals can exercise flexibility to accommodate the cultural practice in engaging patients and their families in ACP discussion.

Contributions & limitations

Given the heterogeneity of the included studies, a meta-analysis was not appropriate. Therefore, thematic synthesis was performed.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to include both Chinese-language and English-language publications on studies of the barriers and facilitators of ACP in healthcare settings. This study also adopted a new framework to structure the factors from the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and socio-environmental dimensions and explained the interweaving nature and the bidirectional force of the factors. Healthcare settings is a common location for ACP discussion, yet there is no systematic review on factors affecting ACP discussion in such settings and this study addresses this research gap and offers valuable information to clinical practice and future research.

Author contributions

MS coordinated the study, AC supervised the study process and MS, AC, RW, and SKY contributed substantially to the review and data extraction. MS and AC drafted the original manuscript and all authors provided critical feedback to several drafts of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this article’s research, authorship, and/or publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research for this article, authorship, and/or publication.