There is a global consensus among key stakeholders that spirituality is an important component of health that should be integrated at all levels of health care. At the 37th World Health Assembly in 1984, the spiritual dimension was included in the health strategies of the Member States of the World Health Organization (1984). Accordingly, spirituality is a key component of overall well-being and it assumes multidimensional and unique functions. Individualized care that promotes engagement in decision-making and considers patients’ spiritual capacity is essential for promoting patient empowerment, autonomy, and dignity (Chirico Reference Chirico2016). For nursing science and practice, this means that the focus of care should not only be on quality of life but also on the meaning of life, to promote health and well-being (Ross et al. Reference Ross, Giske and Boughey2022). In palliative care, undergraduate nurses are expected to (1) grasp the meaning of spirituality and its importance to patients; (2) learn to conduct assessment of the spiritual needs; (3) support patients with spiritual needs; and (4) finally demonstrate openness and confidence toward spiritual, religious, and existential issues (Hökkä et al. Reference Hökkä, Ravelin, Vereecke and Ammattikorkeakoulu2023). This means that nurses’ spiritual capacity building is of paramount importance.

However, nursing science and practice has recognized spirituality as an important aspect of holistic patient care. Different worldviews determine the extent of the focus on spirituality in existing nursing theories (Martsolf and Mickley Reference Martsolf and Mickley1998). A strong philosophical argument has been made that it is more useful to develop a thin, vague, and functional understanding of what spirituality and its cognates might mean and do in the world of health care. At the same time, contending that such a thin, plural, and functional understanding can have profound social and political implications for the way health care is delivered and experienced by patients, carers, and staff alike (Swinton and Pattison Reference Swinton and Pattison2010). On the other hand, it has been argued that as long as the concept of spirituality in nursing remains undefined, models of spiritual care developed for nursing practice will be difficult for nurses to apply (Pike Reference Pike2011).

Concepts comprise some of the most fundamental entities or phenomena associated with a discipline (Cocchiarella Reference Cocchiarella, Poli and Simons1996, 8); hence, they are a crucial part of constructing any theoretical framework. Presenting concepts as objects, they equally have the potential of becoming intentional objects of fiction and stories of all kinds (Ibid., 60). A conceptual analysis conducted by North American researchers found that spirituality in the nursing and health literature was defined within the framework of 4 main themes: (i) spirituality as religious beliefs and value systems (spirituality = religion); (ii) spirituality as meaning of life, purpose in life and connection with others; (iii) spirituality as nonreligious beliefs and value systems; and (iv) spirituality as metaphysical or transcendent phenomena (Sessanna et al. Reference Sessanna, Finnell and Jezewski2007). Researchers working in South Africa defined spirituality in nursing as a unique individual endeavor to establish and maintain a dynamic transcendent relationship with self, others, and God/supernatural being as understood by the person (Chandramohan and Bhagwan Reference Chandramohan and Bhagwan2016). Another conceptual analysis of spirituality in nursing conducted by Iranian researchers found that the concept of spirituality has different meanings depending on cultural and philosophical factors. In fact, it is a completely context-dependent concept (Razaghi et al. Reference Razaghi, Rafii and Parvizy2015). Subsequently, “Spirituality is never given to us as some sort of neatly wrapped gift, which we then unpack and can apply to all places at all times and in all circumstances. Rather, the meaning of spirituality is necessarily emergent and dialectical; it is shaped and formed by the context within which spiritual language is expressed” (Swinton and Pattison Reference Swinton and Pattison2010, 230).

The primary reason for having a clear definition is to understand the meaning of an idea or concept. The secondary reason for striving for a robust definition is to determine how that idea or concept relates to theory and practice. In theory, the lack of a robust definition and operationalization of the concept has implications for research on spirituality in nursing. In practice, for example, the demarcation between spirituality and religion is recognized as cause for problematic dichotomies in patient care (Pesut Reference Pesut2008). Furthermore, the lack of “precise” terminology in terms of the language used to define spirituality has impeding implications for nursing practice and education (Clarke and Baume Reference Clarke and Baume2019; McSherry et al. Reference McSherry, Cash and Ross2004).

German-speaking nurses agree that spirituality and spiritual care are an integral part of professional nursing, which should be a cue for educators, academic leaders, and nursing associations to include the topic in further discussions (Brandstötter et al. Reference Brandstötter, Sari Kundt and Paal2021b; von Dach and Osterbrink Reference von Dach and Osterbrink2013). However, due to the indeterminacy of the concept of spirituality, further research is needed to fully understand nurses’ views on spirituality. This would provide evidence and language to make theoretical frameworks of spiritual care accessible and applicable in everyday practice (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Washington and Kearney2022), and consequently improve care quality and nurses well-being (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Paal and Symons2021a; Paal et al. Reference Paal, Helo and Frick2015). For this reason, the question “How do nurses define spirituality for themselves?” remains of great importance for improving patient care, education, and research. This article provides a conceptual analysis of the understanding of spirituality by German-speaking nurses in an educational context.

Methods

Conceptual analysis is traditionally linked to the research design of philosophical enquiry in the principle of verifiability or the criterion of meaningfulness. The purpose of philosophical enquiry is to clarify meaning through intellectual analysis. In empirical research, the method of conceptual analysis is used to investigate and modify the explicit conceptual theory of language (Wittgenstein (2001) 1953). The technique of conceptual analysis is concerned with precisely defining the meaning of a particular concept by identifying and specifying the conditions under which an entity or phenomenon applies (Kipper Reference Kipper2012, 9). Conceptual analysis in practice concerns distinguishing terms, analyzing the understandings they refer to, and representing this.

Context

Lectures on spiritual care in nursing have been offered to nursing students at the Paracelsus Medical University since 2019 (Brandstötter et al. Reference Brandstötter, Sari Kundt and Paal2021b). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the restructuring of the bachelor degree, the course on spirituality in nursing was moved online in 2021. Taking advantage of this challenge and opportunity, the course has been redesigned based on the Gold Standard Matrix for Spiritual Care Education for Nursing and Midwifery Students (Ross et al. Reference Ross, Giske and Boughey2022). Accordingly, students are expected to understand the importance of the spiritual dimension at intrapersonal and interpersonal levels and have practical experience in patient assessment, care planning, and intervention. An exercise in self-reflection and a thorough assessment of spiritual well-being, attitudes, and competencies is included to help students understand their own values and beliefs, strengths, and limitations. Compulsory reading material (Brandstötter et al. Reference Brandstötter, Grabenweger and Lorenzl2021a) is provided to help students understand the concepts of spirituality, spiritual dimension, and spiritual care and to familiarize themselves with common assessment strategies before attending the online lecture.

Data collection

During the online lecture (with a maximum of 10 participants), participants are invited to write down their personal understanding of spirituality “Spirituality for me is/means…” (Spiritualität bedeutet/ist für mich…) using Padlet (www.padlet.com). Padlet is a cloud-based software-as-a-service that hosts a real-time collaborative web platform where users can upload shared content to virtual pin boards. In general, Padlet is only viewable by course participants. However, all definitions posted in previous lectures are projected and students are encouraged to read the existing definitions. Demographic data were also collected.

Data analysis

Conceptual analysis determines the existence and frequency of concepts in a text. For this purpose, all definitions received from students were downloaded, cleaned, and saved as a pdf file. To identify the frequency of concepts in the spirituality definitions, the pdf file was uploaded to the free text analysis tool speak.ai (https://speakai.co/tools/). The 200 most frequent words were included for analysis and transferred to an Excel document, where they were compared, organized into various columns, color coded, and classified into categories and subcategories. The analysis process was repeated several times by one experienced qualitative researcher. For the relational analysis, the second important step in conceptual analysis, the relationships between concepts were examined and determined.

Rigor and trustworthiness

Each qualitative research approach has specific techniques for conducting, documenting, and evaluating data analysis processes, but it is the individual researcher’s responsibility to assure rigor and trustworthiness (Nowell et al. Reference Nowell, Norris and White2017). The researcher who collected and conducted the analysis first read through all definitions available to become familiar with the data. Although the text analysis tool speak.ai provided information on the most frequent concepts by default, the analysis focused on all concepts without quantification.

The conceptual analysis was initially inductive, but the concepts resonated with the concept analysis questions: (i) what aspects or characters are linked to spirituality? and (ii) how is spirituality experienced, practiced, and lived? Hence, the inductive approach applied merely to identifying the subcategories. To refine the subcategories, the concepts were combined, split up, and discarded several times. Interlinks between the subcategories were expected as all these concepts were initially used to define one concept “spirituality.”

The concept analysis was carried out in German. The concepts, categories, and subcategories were translated into English to be presented in this article. Both German- and English-speaking authors of this paper held consensus discussion to analyze and break down the concepts including the search for their definition. For example, an initial subcategory “to be content with my own ideas” was renamed “to be content with myself” in the English consensus round. A subcategory “capacity” could also be called place or space, a direct translation of the German concept “Raum”; however, “capacity” also includes the potential of the place, space, or situation to enable spirituality, as presented in an article that investigated nurses’ spirituality in German-speaking countries (von Dach and Osterbrink Reference von Dach and Osterbrink2013).

The German concepts are presented here in the original language, as the semantic connotations differ between German and English. Examples of subcategories are selected to create a better understanding of how the identified concepts are used in nursing students’ definitions of spirituality. According to the spiritual care and nursing theory presented above, the strength of the concept of spirituality lies both in its precision in a given context and in its indeterminacy. So, the analysis overall did not seek consensus. The aim of the conducted analyses was to define and present the concepts with all their facets and complexity.

Researcher’s positioning

Originally, the term “positioning” has been described as a communicative approach in which people participate in conversations as observable yet subjectively coherent participants in jointly produced interpretations (Davies and Harré Reference Davies, Harré, Harré and van Langenhove1999, 37). A systematic review of the impact of spiritual care training found that developing health professionals’ sensitivity to their own spirituality was the most important step in developing spiritual care skills, and that spiritual care was not just about asking the “right” questions but also about listening, being present and available, and being free from stereotypes toward different cultures and religions (Paal et al. Reference Paal, Helo and Frick2015). Over the years, the first author (PP) of this article has worked on teaching strategies that help nursing students to self-reflect on several levels. The Padlet exercise was created with the purpose of addressing the nursing students’ understanding of spirituality in the educational context and demonstrating the variety of such understandings in an anonymous, and thus, safe environment.

Results

The data collected consisted of 83 definitions of spirituality. Nonparticipation was related to technical problems, time constraints, or a personal choice.

Participant demographics

A total of 91 nursing students, of which 76 (83.5%) identified as female and 15 (16.5%) male, took the spiritual care course between January 2022 and January 2023. The majority of participants were in the 26- to 40-year age bracket (n = 63, 69.6%). Of all participants, 84 (92.3%) currently worked in clinical practice and 7 (7.7%) answered no to this question, but this did not mean they were inexperienced. To the question “How would you describe your worldview (Weltanschauung)?,” 50 (54.9%) identified themselves as Christian, 15 (16.5%) chose other, 12 (13.2%) atheist, 6 (6.6%) humanist or agnostic, and 2 (2.2%) Buddhist.

The results of conceptual analysis

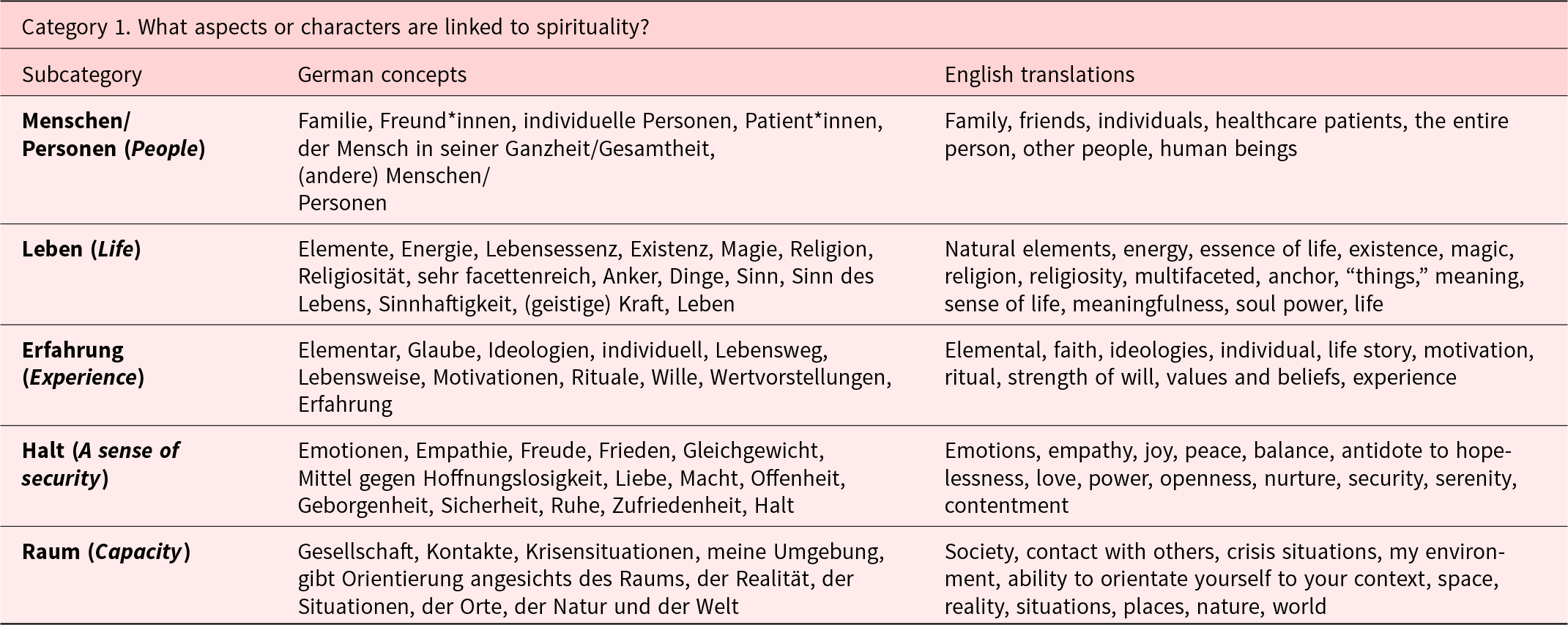

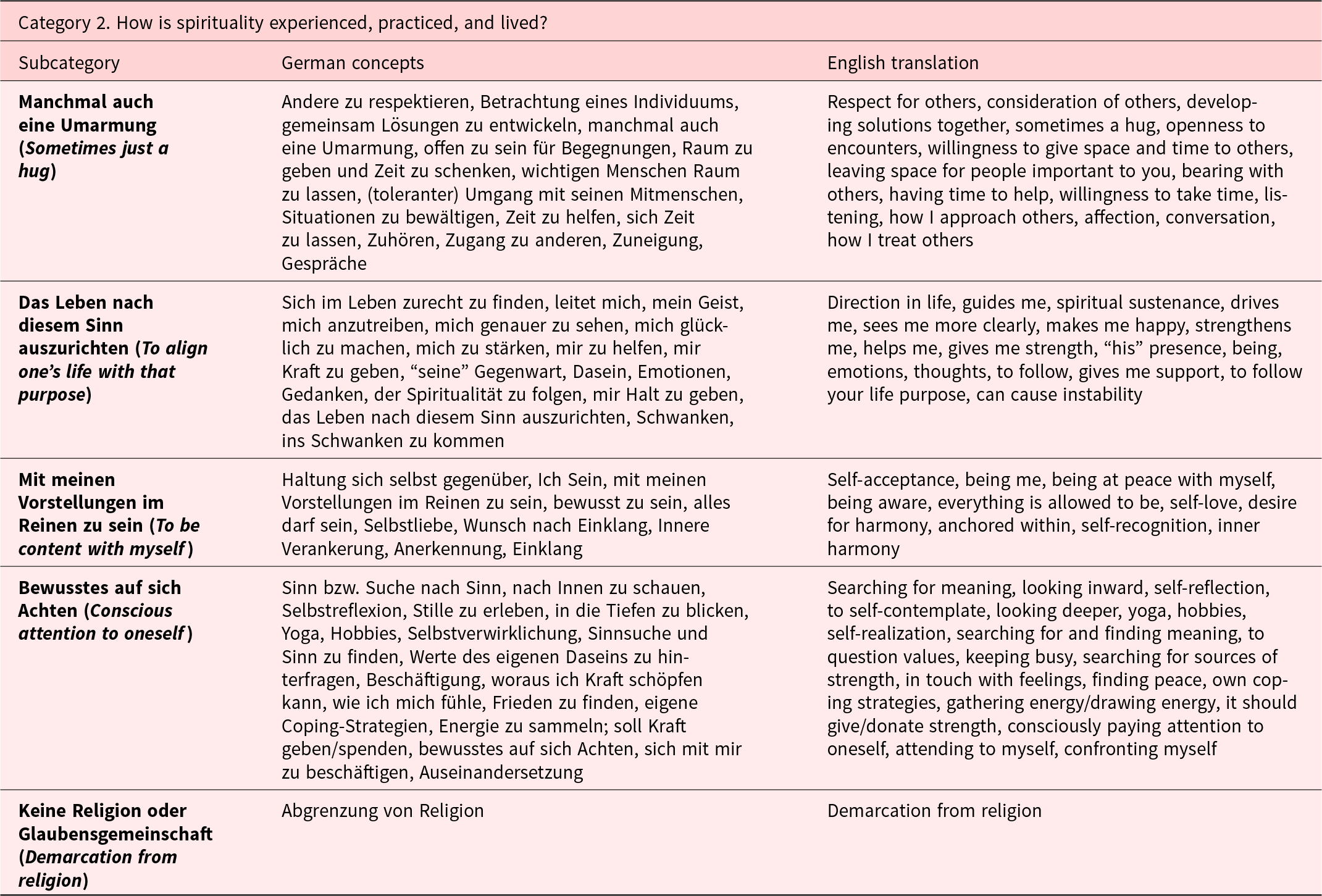

The conceptual analysis resulted in two main categories. The first category describes what aspects or characters are linked to spirituality, including people, phenomena, capacity, and places (see Table 1). The second category explores how spirituality is experienced, practiced, and lived, including being, contemplation, and practices (see Table 2).

Table 1. What aspects or characters are linked to spirituality?

Table 2. How is spirituality experienced, practiced, and lived?

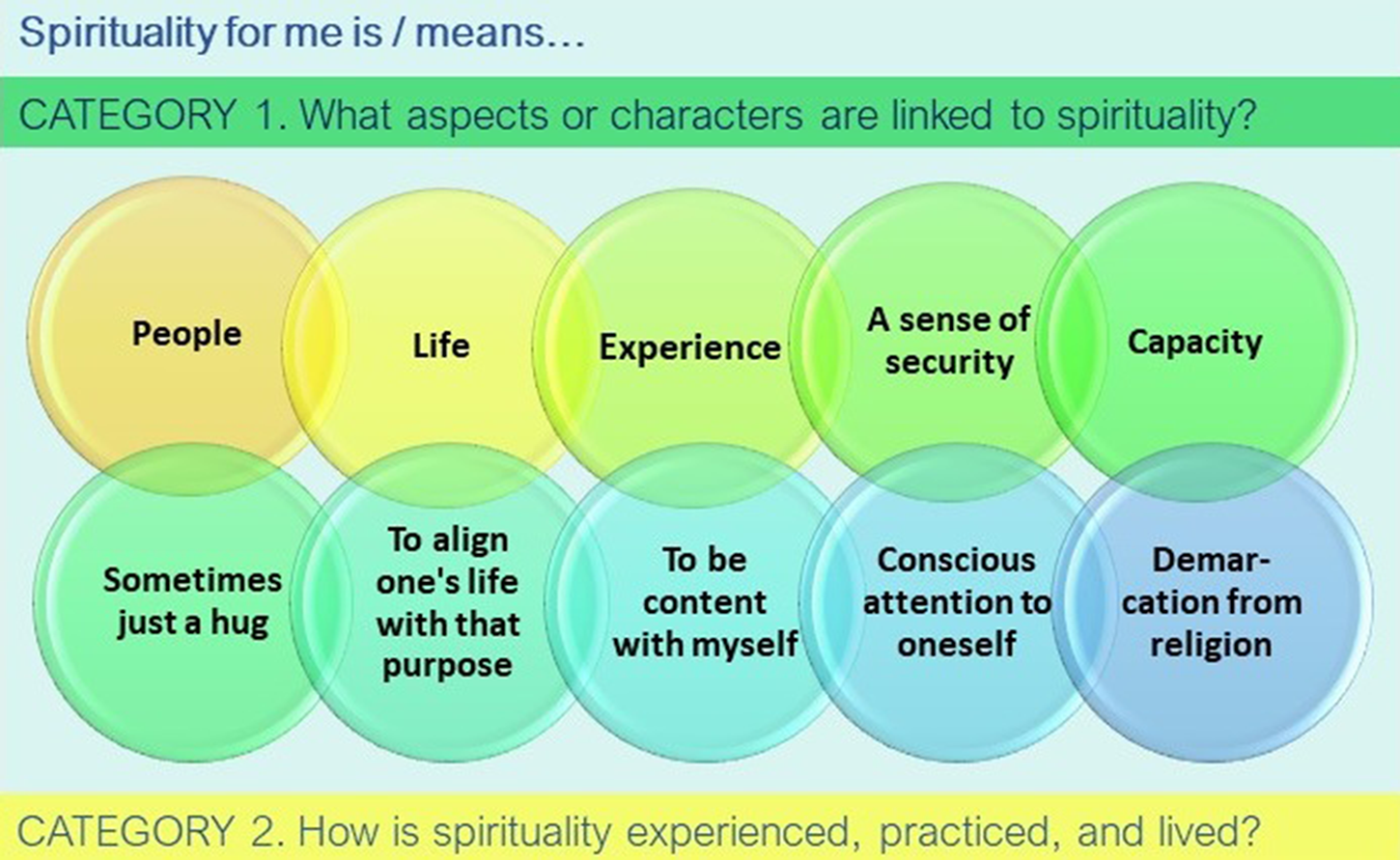

These categories, each with 5 subcategories, are summarized in Figure 1. This figure illustrates the interlinking of the subcategories. For instance, the subcategory “People” is linked with the subcategory “Sometimes just a hug,” as it indicates a way to interact with people. The subcategories within each category are also linked, because “Being content with myself” means also paying “Conscious attention to oneself.” See examples below.

Figure 1. Categories and subcategories of spirituality definition.

Category 1. What aspects or characters are linked to spirituality? Spirituality is people, life, experiences, sense of security, and capacity. The subcategory “People” (Menschen/Personen) refers to friends, family, other people, and patients, and emphasizes individual characteristics as well as the claim to wholeness.

Spiritual care ist für mich Unterstützung von Freunden oder der Familie in schwierigen Zeiten des Lebens zu bekommen. (For me, Spiritual Care is support from friends or family during difficult times in one’s life).

Spiritualität bedeutet für mich Leben als gesamter Mensch. Gesehen werden als individuelle Person und andere Menschen als Gesamtbild zu sehen. (For me, spirituality means living as a whole human being. Being seen as an individual and seeing others in all their complexity).

According to the concepts collected, the second subcategory “Life” (Leben) consists of transcendent aspects such as elements, energy, essence, magic, religion, and religiosity. It is understood to be multifaceted, relating to meaning or sense of life, underpinned by (spiritual) power, anchors, and “the things” (Dinge) of life.

Spiritualität kann für jede Person etwas Anderes bedeuten. Für den einen mag es eine Religion sein, die in bestimmten Situationen hilft Dinge zu verstehen. Für andere entsteht die Sinnhaftigkeit durch andere Elemente, wie zum Beispiel das Vertrauen in die eigene Kraft. (Spirituality means something different for each person. For one, it may be a religion that helps them understand certain situations. For others, the meaningfulness comes from other aspects, such as trusting in one’s own strength).

Spiritualität bedeutet für mich mein Anker, sei das der Glaube die Freunde/Familie oder Musik etc., ein Anker, welcher mich dort hält, wo ich sein möchte, aber gleichzeitig auch dort hin wandern kann, wo ich ihn haben möchte. Durch diesen Anker erfährt mein Leben Sinn und Halt, und wenn dieser Anker ins Schwanken kommt, kommt auch der Glaube an die Sinnhaftigkeit im Leben ins Schwanken. (For me, spirituality is my anchor, be it faith, friends/family or music etc. An anchor that holds me where I want to be, but at the same time allows me to take it where I want it to be. Through this anchor I experience meaning and support in my life. When this anchor falters, the belief in the meaningfulness of life falters as well).

The third subcategory refers to “Experiences” (Erfahrung) that are seen as elemental or based on beliefs and ideologies, but also on individual motivations, wills, values, and preferred ways of living.

Spiritualität bedeutet, sich mit dem eigenen Dasein, der Rolle im eigenen Leben und dem Leben anderer zu befassen sowie darin eine Sinnhaftigkeit zu erkennen. (Spirituality means to be concerned with one’s own existence, the role in one’s own life and the lives of others, as well as to see a meaningfulness in that).

Spiritualität bedeutet für mich meine Antriebskräfte und Halt (Glaube, Motivationen, Ideologien, höherer Sinn) meines Handelns und Denkens. (For me, spirituality means my driving power and contentment (faith, motivation, ideologies, higher sense) of my acting and thinking).

The fourth subcategory “A sense of security” (Halt) includes various positive and negative emotions such as empathy, joy, peace, balance, love, strength, openness, safety, security, serenity, contentment, but also hopelessness.

Spiritualität ist eine Kraft, die mir hilft, herausfordernde Situationen zu bewältigen und zu akzeptieren. (Spirituality is a force that helps me to cope and accept challenging situations).

Spiritualität ist für mich offen zu sein - frei in seinen Gedanken. Es soll Kraft schenken von der man neue Energien ziehen kann, um den Alltag zu meistern. Auch Offenheit und Akzeptanz für Mitmenschen ist wesentlich. (For me, spirituality is to be open minded - free in one’s thoughts. It should give strength from which one can draw new energy to master everyday life. Being open and accepting other people is crucial as well).

And the last subcategory “Capacity” refers to situations and places that make spirituality possible, such as society, contact, crisis situations, environment, orientation, space, reality, nature and the world.

Für mich geht es bei der Spiritualität um die Suche nach dem richtigen Platz im Leben, sich mit den richtigen Menschen zu umgeben, um eine gewisse Geborgenheit und Liebe zu erfahren. (For me, spirituality is about searching for the right place in life, surrounding yourself with the right people, experiencing a certain nurture and love).

Category 2. How is spirituality experienced, practiced, and lived? Spirituality is more than a “Thing” (Ding); it is also an action. It is also contemplation, being, guidance, and confrontation. It is described as a way of approaching people, a particular way of life, a state of being, but also conscious attention to oneself and one’s own abilities. The first subcategory “Sometimes just a hug” (Manchmal auch eine Umarmung) calls for respecting other people, just being with them, and dealing with them with consideration of their individual needs. This means giving space and taking time to make mutually satisfactory decisions by having conversations, showing affection, and listening in order to deal with different situations.

Spiritualität sind für mich bewusste und offene Begegnungen mit der Natur, Menschen, Dingen und mit mir selbst. (For me, spirituality is a conscious and open encounter with nature, people, things and myself).

The second subcategory “To align one’s life with that purpose” (Das Leben nach diesem Sinn auszurichten) includes beliefs and values that guide one’s life, their worldview (Weltanschauung). It is the essence that makes people happy, provides support, and gives strength. It is described as a presence that helps one to be in tune with emotions and thoughts, but it can also cause one’s life to become unbalanced and fluctuate.

Spiritualität bedeutet für mich, sich auf der geistigen Ebene zu befinden. Spiritualität ist eine tiefe menschliche Erfahrung. (For me, spirituality means being on the mental plane. Spirituality is a deep human experience).

Compared to the second subcategory, the third subcategory “To be content with myself” (Mit meinen Vorstellungen im Reinen zu sein) is directly related to the attitude toward oneself, being at peace with oneself, being conscious, looking at things in self-love, desiring harmony and recognition, being completely content and fulfilled (anchored).

Spiritualität bedeutet für mich Sinn im Leben zu finden und mit meiner Umwelt im Reinen zu sein. (For me, spirituality means to find meaning in life and being at peace with my surrounding).

In contrast to subcategories 2 and 3, subcategory 4 “Consciously paying attention to oneself” (Bewusstes auf sich Achten) focuses on conscious engagements, such as searching for meaning, self-reflection, questioning one’s own values, and searching for sources of energy and (spiritual) power. This subcategory stands for active practices, such as keeping busy, engaging in hobbies. playing sport, making music, or practicing yoga.

Spiritualität ist Sinnsuche und Sinnfindung in einer außergewöhnlichen Situation. (Spirituality is the search for meaning and to find meaning in an extraordinary situation).

Spiritualität beschreibt den intrinsischen Wunsch nach Einklang und Verständnis im Leben. Sowohl in der Beziehung mit sich selbst oder einer höheren Existenz als auch im Kontakt mit seinen Mitmenschen. (Spirituality describes the intrinsic desire for unity and understanding in life. Both in relationship with oneself or a higher being and in contact with other humans.)

The fifth subcategory is “Demarcation from religion” (Keine Religion oder Glaubensgemeinschaft). It refers to the distinction between definitions of spirituality and religious beliefs or religiosity.

Spiritualität bedeutet für mich, mich selbst und mein Umfeld gut zu spüren und mit mir selbst im Reinen zu sein. Religion spielt dabei für mich keine Rolle. (For me, spirituality means sensing myself and my surrounding and being at peace with myself. Religion plays no role for me in this).

Spiritualität ist für mich keine Religion oder Glaubensgemeinschaft, sondern ein individuelles Erleben und Fühlen in angenehmen sowie schwierigen Situationen oder Zeiten. (For me, spirituality is not a religion or religious community but an individual experience of pleasant as well as difficult situations or times).

Discussion

In nursing practice, the integrated person model suggests that within each individual the dimensions of body, mind, and spirit are connected, with each dimension influencing the others. While spiritual care has been widely researched, some nurses can find it challenging to implement in their everyday practice (Clarke Reference Clarke2013; Clarke and Baume Reference Clarke and Baume2019). In 2021, a systematic review of the conceptual framework of spirituality in health care was published, arguing that understanding spirituality is an important topic for research, clinical practice, and health professional education. A total of 166 articles, most of them in English, were included in the final analysis regarding spirituality definitions. Twenty-four spirituality dimensions were identified. The dimensions were recognized by identifying terms or expressions that were common to at least 3 different spirituality definitions, for example, terms such as “connection,” “God,” and “life after death” (De Brito Sena et al. Reference De Brito Sena, Damiano and Lucchetti2021). This study emphasizes the highly contextualized definition of spirituality, which clearly represents a barrier to a universal definition of spirituality and contradicts the plea for “a clear concept that suits the everyday professional context” (Weiher Reference Weiher2022). Furthermore, the findings suggest that conceptual analysis is highly useful for the field of education and training.

Contextualization of the data collection

It should be noted that, before providing their “definition of spirituality,” the nursing students had participated in a survey that asked them to reflect on their spiritual well-being, attitudes, and competencies (Brandstötter et al. Reference Brandstötter, Sari Kundt and Paal2021b). This may have influenced the answers given. However, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic, nursing students report that such reflection on personal well-being and practice is personally rewarding. The survey and the reading material (Brandstötter et al. Reference Brandstötter, Grabenweger and Lorenzl2021a) were described by participants as helpful to position oneself and the role of spirituality in nursing practice.

Common feedback, gathered during the online lectures, was that spiritual care is an essential part of nursing practice, but nursing students are not familiar with the concept of spiritual care (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Washington and Kearney2021b). Considering that 92.3% of course participants work in clinical practice and a majority of them (69.6%) belong to the age-group 26–40 years indicates that spirituality is not discussed much in their workplaces. Another common response is that they were initially hesitant about this course because their basic idea of spirituality is much more rigid and associated with religion.

The Padlet exercise suggests that the student nurses have sufficient vocabulary and understanding to define their personal understanding of spirituality. As the training takes place online, it cannot be ruled out that participants used internet search engines for additional support. However, the time frame for this task was limited to about 10 minutes, so it is to be expected that they drew on their previous reflection exercises, the reading material, and the facilitated discussion when formulating their understanding of spirituality.

Tenuousness of nursing students’ spirituality

In World Health Organization’s Health for All strategy, the spiritual dimension is defined in accordance with people’s own social and cultural patterns recognizing that “the spiritual dimension plays a great role in motivating people’s achievements in all aspects of life.” The complete description of the spiritual dimension as articulated by the Health Assembly’s Resolution WHA31.13 as follows: “The spiritual dimension is understood to imply a phenomenon that is not material in nature, but belongs to the realm of ideas, beliefs, values and ethics that have arisen in the minds and conscience of human beings, particularly ennobling ideas. Ennobling ideas have given rise to health ideals, which have led to a practical strategy for Health for All that aims at attaining a goal that has both a material and nonmaterial component. If the material component of the strategy can be provided to people, the nonmaterial or spiritual one is something that has to arise within people and communities in keeping with their social and cultural patterns. The spiritual dimension plays a great role in motivating people’s achievement in all aspects of life” (World Health Organization 1991).

These findings, which are aligned with the World Health Organization’s definition of spiritual dimension “as a non-material component that has to arise within people and communities in keeping with their social and cultural patterns,” demonstrate that German-speaking nurses’ definitions of spirituality are manifold and individual. Nolan and colleagues have identified the challenge of finding a workable definition for spirituality that embraces the richness of spiritual diversity while at the same time finding common ground (Nolan et al. Reference Nolan, Saltmarsh and Leget2011). Most commonly, the notion of spirituality is approached as encompassing religious and existential domains that combine theistic and secular world-views in an individual’s belief system (Breitbart Reference Breitbart2007; la Cour and Hvidt Reference la Cour and Hvidt2010). The World Health Organization’s definition of spiritual domain points out that “by virtue of being human.. everyone is spiritual” (Burkhardt and Nagai-Jacobson Reference Burkhardt, Nagai-Jacobson, Blaszko-Helming, Shields, Avino and Rosa2016, 121). However, spirituality needs to be discovered and defined at an individual level, and only then it can be activated to expand the professional scope, and thus improve the connection and collaboration between nurses and people they take care of (Paal et al. Reference Paal, Helo and Frick2015).

In addition to thin, vague and functional understanding of spirituality (Swinton and Pattison Reference Swinton and Pattison2010), our results also identify the potential fragility of nurses’ spirituality, with terms such as hopelessness, meaninglessness, and lack of stability used by some participants. Guidance for educators designing spiritual care nursing programs has been presented (Ross et al. Reference Ross, Giske and Boughey2022). In view of findings that one’s own spiritual well-being is influential in determining one’s competence in spiritual care and ability to provide it (Best et al. Reference Best, Butow and Olver2016), clinical institutions should prioritize supporting the spiritual well-being of their staff. This does not have to be a significant undertaking but does require consistency. Accessible and feasible options which enable this have been identified in the health-care sector (Best et al. Reference Best, Leget and Goodhead2020).

Concept analysis and conceptual analysis

In nursing science, the Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis has been established as a valid and necessary scientific approach. Rodgers’ has pointed out that concepts develop over time and are influenced by the context in which they are used. The purpose of concept analysis is to analyze, define, develop, and evaluate concepts used in the nursing profession. Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis is an inductive and highly systematic method of analysis, typically based on scientific literature (Rodgers Reference Rodgers, Rodgers and Knafl2000). A concept analysis of spirituality in nursing has been conducted (Razaghi et al. Reference Razaghi, Rafii and Parvizy2015). Conceptual analysis is the philosophical analysis or breakdown of concepts for explicit and implicit meaning making. Bearing in mind what Wittgenstein in his Philosophical Investigations (Wittgenstein (2001) Reference Wittgenstein1953) has called the rough ground of ordinary language in use and deliberately not forgetting the muddying effects of everyday contexts. In its essence, conceptual analysis is less systematic, highly interpretative approach, based on deductive reasoning, equally useful for analyzing, describing, and revealing the content of the concept. Conceptual analysis can be helpful to analyze concepts that are theoretical, or as in case of spirituality, that are normally not addressed or analyzed in clinical conversations (Mayr et al. Reference Mayr, Elhardt and Riedner2016; Paal et al. Reference Paal, Frick and Roser2017). Hence, both approaches – concept and conceptual analyses – to advance nursing science are useful, as concepts are constantly undergoing dynamic development and redefining how the analysis of a concept’s context, surrogate and related terms, antecedents, attributes, examples, and consequences occurs. Such analysis merely indicates a direction for further research and does not provide a definite conclusion (Tofthagen and Fagerstrøm Reference Tofthagen and Fagerstrøm2010).

Implications for further research

An umbrella review of spiritual care education (Brandstötter et al. Reference Brandstötter, Grabenweger and Frick2022) found that the teachers and clinicians in the field of spirituality studies are predominantly from a Christian background, which is rarely addressed as a bias. Concerns are raised that spiritual care education may be discriminatory if only the major world religions are addressed or their contribution is neglected in the curricula. Furthermore, there is no clarity on how to address the needs of agnostics or atheists or how multi-denominational the content actually is. Therefore, spiritual care training programs may have negative effects on students, such as anxiety and feeling pressured to change one’s views on spirituality. These findings demonstrate the fragility in the nurse students’ spirituality definitions, which is directly related to nurses’ poor spiritual well-being. These problems require a value-free assessment to improve nurse education and enable nurses to recognize, embrace, and improve this human virtue as well as nursing practice.

Conclusions

A conceptual analysis was conducted to analyze the nurses’ definitions of spirituality. The analysis did not aim to reach a consensus but to define and present the concepts of spirituality with all their facets and complexity. In addition to thin, vague, and functional understanding of spirituality, our findings also highlight the understanding of spirituality as a fragile concept, which interlinks with the potential tenuousness of nurses’ spiritual well-being, with terms such as hopelessness, meaninglessness, and lack of stability used by some participants. If nurses do not have the opportunity to understand and verbalize what spirituality means in their lives, and definitions are implied without understanding, the result may be that teaching is discriminatory and thus hinder the inclusion of spiritual care as an essential component of nursing practice with all its benefits.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the student nurses who shared their perceptions and genuine interest in enabling spiritual care in nursing practice.

Ethical approval

The local ethics committee in Salzburg, Austria, was contacted but deemed the study on students exempt from ethical approval. The students gave their written consent to use this data for published research. All contributions were anonymous, and participation in the research part of the lecture was voluntary.