Introduction

Providing patient-centered care respectful of and responsive to individual patient goals and treatment preferences is fundamental to improving the quality of care and patient experience, particularly during serious illness (Heyland et al. Reference Heyland, Heyland and Dodek2017). A goals-of-care discussion, broadly referred to as end-of-life (EOL) decision-making, is an interactive clinician–patient dialogue whose purpose is to create a shared understanding of patient goals and preferences (Sanders et al. Reference Sanders, Curtis and Tulsky2018). Goals-of-care discussions provide a useful tool to empower patients and their significant others, allowing them to identify their priorities and decide about the level of treatment intensity (Kaldjian Reference Kaldjian2020).

Discussing goals of care

Because of a lack of prognostication and therefore complex decision-making about the level of treatment intensity in serious illness, involving patients and family members is crucial for better outcomes (Chu et al. Reference Chu, White and Stone2019; Dalgaard et al. Reference Dalgaard, Bergenholtz and Nielsen2014). Available evidence reveals that discussing goals of care is associated with less hospitalization and treatment intensity and reduced levels of stress and depression (Jimenez et al. Reference Jimenez, Tan and Virk2019; Mack et al. Reference Mack, Cronin and Keating2012; Marchi et al. Reference Marchi, Santos Neto and Moraes2021). Suffering from serious illness and poor experiences of EOL become evident when clinicians do not discuss and consider goals of care and rely on standard, life-sustaining treatments (Bernacki and Block Reference Bernacki and Block2014). The available evidence on the perceived experiences during goals-of-care discussions and perspectives of EOL decision-making is mainly based on quantitative studies that address the caregivers’ and clinicians’ standpoints and provide little understanding of the patients’ viewpoints (Jimenez et al. Reference Jimenez, Tan and Virk2018).

The context in Jordan and culturally similar Arab countries

Jordan is a developing Middle Eastern country with an estimated population of 11 million in 2022, of which 97% affiliate with Islam and virtually all of whom share the linguistic and cultural Arab identity (The World Factbook 2022). Serious illness in Jordan is increasingly prevalent, particularly in terms of incurable conditions such as advanced cancer and end-stage renal disease (Abdel-Razeq et al. Reference Abdel-Razeq, Attiga and Mansour2015; Khalil et al. Reference Khalil, Abed and Ahmad2018). This is concerning because the growth of palliative care has been slow and access to such health-care services remains limited (Shamieh and Hui Reference Shamieh and Hui2015). Jordan lacks a national policy to ensure honoring the patient’s preferences for EOL.

In terms of EOL decision-making in Jordan, the situation is complex at various levels. First, the sociocultural norm is that families make health-related decisions on behalf of the patient and withhold any bad news about the diagnosis and prognosis, which could be related to fears that confronting the patient with the possibility of poor outcomes and inevitable death may worsen the anxiety in the patient (Shamieh et al. Reference Shamieh, Richardson and Abdel-Razeq2020). Second, there exist religious challenges due to confusion between euthanasia and the patient’s right to choose treatment preferences (Sultan et al. Reference Sultan, Mansour and Shamieh2021). Specifically, while euthanasia is forbidden in Islam based on the basic principle of preserving life and people’s accountability for their bodies that are viewed as gifts from Allah, Islamic rulings permit the act of withholding and withdrawing life-supporting treatments if there is medical consensus that treatments are futile (Malek et al. Reference Malek, Abdul Rahman and Hasan2018). The Islamic rulings pertaining to EOL decision-making are clear; however, euthanasia may be wrongly synonymized with forgoing life-sustaining treatments under certain conditions, which can be a source of confusion. Third, aside from the religious challenges, there exists a lack of a culture of shared decision-making between patients and their clinicians, mainly due to sociocultural norms, low health literacy, and a lack of knowledge about shared decision-making (Khader Reference Khader2017; Obeidat and Khrais Reference Obeidat and Khrais2016; Othman et al. Reference Othman, Khalaf and Zeilani2021; Zisman-Ilani et al. Reference Zisman-Ilani, Obeidat and Fang2020). Finally, the absence of clinician training on handling uncomfortable situations, such as breaking bad news and discussing EOL topics, serves as a health-care system barrier (Gustafson and Lazenby Reference Gustafson and Lazenby2019).

While under-researched, the status of EOL decision-making in other Middle Eastern and Muslim-majority countries that share the linguistic and cultural Arab identity is like that of Jordan (Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Connor and Clark2013; Osman and Yamout Reference Osman, Yamout, Al-Shamsi, Abu-Gheida and Iqbal2022). Only a handful of studies were conducted in these countries concluding that patients would like to talk about EOL (Bar-Sela et al. Reference Bar-Sela, Schultz and Elshamy2019a; Dakessian Sailian et al. Reference Dakessian Sailian, Salifu and Saad2021), emphasizing the need for practice regulations based on the opinions of patients in Lebanon (Doumit et al. Reference Doumit, El Saghir and Abu-Saad Huijer2010), clinicians in Saudi Arabia (AlFayyad et al. Reference AlFayyad, Al-Tannir and AlEssa2019), and scholars in Saudi Arabia (Arabi et al. Reference Arabi, Al-Sayyari and Al Moamary2018; Woodman et al. Reference Woodman, Waheed and Rasheed2022).

Overall, the literature mostly documents the Western perspective regarding EOL decision-making; patient views have scarcely been studied from the viewpoint of Jordanians and culturally similar Arab populations, including those in the Islamic faith. This qualitative descriptive study seeks to gain insights into seriously ill patients’ experiences during goals-of-care discussions and perspectives of EOL decision-making in Jordan. We address the following questions: (1) what experiences are shared by patients during goals-of-care discussions, (2) how patients perceive EOL decision-making, and (3) what priorities, goals, and treatment preferences are expressed by seriously ill patients.

Methods

Design

We used a qualitative descriptive design with semi-structured, one-on-one interviews (Colorafi and Evans Reference Colorafi and Evans2016) to provide rich, straight, and low-inference descriptions of the patient’s experiences and viewpoints. This study was developed using a social constructivist worldview (Creswell Reference Creswell2018); it is the authors’ assumption that the sociocultural and religious contexts in Jordan influence how patients experience EOL and perceive decision-making.

Sample and settings

A purposeful sampling technique with a maximum variation strategy was used to recruit Arabic-speaking adults with various serious illnesses who can inform an understanding of the phenomena at hand (Sandelowski Reference Sandelowski2010). Patients were adults; seriously ill, including those who were aware they have an advanced condition, were referred to palliative care, and were no longer receiving curative therapy; hospitalized for at least a day; fluent in Arabic; and willing to volunteer and engage in a 45-min interview. Patients who were too sick to fully engage in a conversation were not included. Settings were 2 large hospitals in Jordan: a university hospital and a nongovernmental, nonprofit cancer center. Samples from the 2 study settings were comparable in terms of population characteristics. Each interview was audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and translated from Arabic into English. The de-identified records were only accessible by the research team.

Data collection

Data were collected in the summer of 2019 through interviews that took place in a private space in the study setting. We used semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions in an interview guide as shown in Table 1. Approved flyers with information about the study and researchers were distributed to potential patients. Individuals who met the inclusion criteria and gave verbal consent were then interviewed. The primary author (A.A.) carried out all the interviews in the patient’s native language of Arabic. To avoid interview-induced burdens, the interviewer initiated a rapport-building process with the patients using scenario-based rather than direct interview questions, which allowed access to the patients’ stories.

Table 1. Interview questions

Data analysis

We used conventional content analysis (Colorafi and Evans Reference Colorafi and Evans2016). Two authors (A.A. and D.A.N.) independently read the transcripts, identified and compared key terms and sentences, and maintained reflexive journals (Rodgers and Cowles Reference Rodgers and Cowles1993). Codes were grouped into categories and topics, which were then organized into subthemes and themes (Sandelowski Reference Sandelowski2010).

Rigor and trustworthiness

This article followed the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research guidelines (Tong et al. Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007). Rigor and trustworthiness in methodology and findings were maintained as summarized in Table 2 (Korstjens and Moser Reference Korstjens and Moser2018; Lincoln and Guba Reference Lincoln and Guba1985; Rodgers and Cowles Reference Rodgers and Cowles1993; Tracy Reference Tracy2010).

Table 2. Rigor and trustworthiness in the study

Results

Fourteen seriously ill patients were each interviewed once. Table 3 illustrates the sample characteristics. Four themes emerged in this study (Figure 1).

Table 3. Sample characteristics (N = 14)

Fig. 1. Study themes and subthemes.

Theme 1: perceived suffering near EOL

Suffering was the topic that patients talked about the most. The shared experiences of suffering while experiencing a serious illness revealed 2 subthemes.

Subtheme 1: disease and treatment burdens

Patients consistently talked about the impact of disease and treatment burdens including “too many health-care encounters” (Patient 5) that are burdensome. Most notably, patients cited unrelieved symptoms, including pain and sleeplessness, as causes of suffering: “Pain is the worst part of it. It is intolerable. Persistent pain. I cannot tolerate it. I cannot sleep because of it” (Patient 1).

Subtheme 2: concerns about life, family, and death

In addition to disease and treatment burdens, patients also noted that common sources of suffering included feeling guilty because significant others were overwhelmed and sad: “They [family members] certainly suffer. I feel I am straining my family’s life, this is bad” (Patient 5). Fear of death and dying alone was another source of suffering: “Dying alone without anyone close to me makes me afraid” (Patient 4). Remarkably, patients perceived uncertainties about prognosis and confusion regarding what would happen next as key sources of suffering: “There is no clear cure plan. It is like there is cure but there is no cure. I expect things would get better while in fact, they get worse. Not sure what will happen next” (Patient 4).

Theme 2: attitudes toward EOL decision-making

In terms of patients’ viewpoints about discussing goals of care and engaging in EOL conversations, responses revealed 3 subthemes.

Subtheme 1: health conditions and a range of psychological, sociocultural, and religious factors influencing EOL decision-making

Throughout the conversations, patients acknowledged the influence of their health conditions and sociocultural and religious aspects on decision-making. For instance, patients indicated that clinicians and family members “tend not to share the diagnosis and progress [with patients], particularly if it was cancer” (Patient 11). This was attributed to efforts “to avoid potential psychological and emotional deterioration due to hearing the bad news” (Patient 14). However, some patients acknowledged such culture should change: “My experience from the beginning, the first surgery, was that my family hid it [cancer diagnosis], but one of them mistakenly said something so I knew it and asked the physician to tell me if it was cancer…. If I have a chance, I will live, otherwise, it is totally fine, I am okay with it, so why are you hiding it?” (Patient 2). It was also acknowledged that clinicians and families like to keep patients away from psychological and emotional disturbances, which “may make the case worse” (Patient 2). One of the sociocultural issues addressed by a few patients was a stigma in which choosing not to continue full treatments could be seen as harming or killing themselves. One patient said this could be considered “an interference with God’s will” (Patient 4). Another patient talked about family members making EOL decisions for their gains: “They [relatives and friends] would say he [son making EOL decision for his father in a scenario] wants to take the legacy and endowment. He wants to benefit from his father’s properties” (Patient 8).

Subtheme 2: uncertainties, lacking awareness, and assumptions of fear leading to reluctance and inaction

Almost all patients had little to no clear understanding of, or previous exposure to, EOL decision-making. After the patients were introduced to the concept of EOL conversations and asked about their own experiences, none of them believed any of their clinicians had ever initiated such a conversation. Most patients cited sociocultural and religious concerns as causes for the lack of EOL conversations. For example, Patient 2 indicated that no one had discussed EOL topics because: “We are in a Middle Eastern society…. It is impossible.” Notably, most patients questioned the legitimacy of EOL decision-making from an Islamic faith perspective. Some patients even believed EOL decision-making was a form of assisted suicide: “This [choosing to decline life-sustaining treatments] is haram [forbidden in Islamic faith]. I think it is considered self-killing” (Patient 13). However, a handful of patients expressed potential interest in engaging in such conversations if, for instance, sociocultural and religious concerns were resolved. Apparently, EOL decision-making is considered taboo: “This [conversation] is strange. Not all people can talk about it and handle it [goals-of-care decisions] the same. Many would refuse to talk about it because people have various levels of intellect, awareness, and ability to handle it” (Patient 1).

Subtheme 3: patients believing clinicians, rather than patients, should make EOL decisions

Surprisingly, none of the patients talked about their right to know and make decisions about their health care. Patients believed the norm was that EOL decision-making was a clinician’s, rather than a patient’s role, simply because “clinicians know much better than patients and family members” (Patient 4). Additionally, one patient emphasized that when there was room for sharing decisions, “families would be involved instead of the ill” (Patient 9).

Theme 3: goals of care and preferences for EOL

Patients’ responses to questions asked about goals and treatment preferences are categorized into 2 subthemes.

Subtheme 1: what matters most is alleviating suffering and getting support from family, friends, and care providers

Most patients consistently indicated that having their suffering alleviated and receiving better care were their chief priorities. For instance, patients wished their unbearable pain and other symptoms would be relieved through enough medication. They also expressed concerns about their medication’s appropriateness and adequacy: “I am on continuous infusion which sometimes is ineffective. Sometimes Morphine does not alleviate pain” (Patient 13). Patients also cited the importance of getting support from their family, friends, and care providers: “A patient whose condition is advanced should meet with their family and relatives which will make them feel better” (Patient 10).

Subtheme 2: patients prefer to live longer, be with family, and die with dignity

Most patients rejected the idea of discontinuing life-sustaining treatments, regardless of their health conditions, mainly because of sociocultural and religious reasons. Nevertheless, patients mentioned multiple preferences that would translate into varying levels of care delivery. For instance, some patients emphasized the need to take standard treatments, which they considered a form of assessing conditions: a religious expression in the Islamic faith implying the need to assess the context and do the best means when making decisions. However, when the interviewer discussed Fatwa No. 3539 of the Jordan Board of Iftaa’ (2019) stating that “If doctors thought that it is most probable that recovery and cardiac resuscitation are hopeless, then they may refrain from conducting any procedure on that patient. This is provided that this decision is supported by a report of an expert medical team comprised of three specialized, honorable and trustworthy doctors, at least,” a handful of patients indicated that, when treatments are futile, it might be better for patients to stay at home with family for more comfort and less suffering, as opposed to dying in the hospital: “He [a patient in a scenario] should assess conditions … but staying at home could be more comfortable to him” (Patient 7). Other patients indicated they would choose to benefit from the available treatments because “there is always hope … and not doing the best means could destroy one’s health, which might be against God’s will and lead to going to hell eventually” (Patient 3). Some other patients stressed that extending the conversation and discussing the various types of goals motivated them to express willingness in choosing comfort-focused care like managing symptoms and dying at home with dignity. Multiple patients emphasized how sad it can be to die lonely when hospitalized near death.

Theme 4: actions to enhance EOL decision-making

In discussions of what is needed to enhance the culture of EOL decision-making, patients’ responses focused on actions that are separated into 2 subthemes.

Subtheme 1: clarifying the legitimacy of EOL decision-making

Patients consistently recommended asking religious experts to clarify the legitimacy of EOL decision-making from an Islamic faith perspective. Some patients stressed that without fatwa (i.e., a ruling on a point of Islamic law given by a recognized authority), most people will be skeptical about EOL decision-making: “No one knows if such questions are halal [allowed] or haram [prohibited]. Show me fatwa” (Patient 6). Some patients highlighted the need to educate people about the Islamic faith rules about certain EOL decisions: “Very few people would accept the idea [EOL decision-making]. Religious experts need to be counseled first. We need to have fatwa and understand the consequences” (Patient 8).

Subtheme 2: preparing patients and families and communicating with them effectively

Patients perceived multiple issues that make EOL conversations taboo in a country like Jordan: “Making decisions depends on the religious, health, and psychological status…. It is not going to be easy for people to make such hard decisions” (Patient 4). For successful implementation, multiple patients emphasized that stakeholders should prepare people for EOL decision-making, considering individual variations in handling goals-of-care discussions. A few patients stressed that patients and families should be prepared mentally and psychologically to engage in such discussions: “They [clinicians] should not add burden to the patient’s psychological status by such [goals-of-care] questions…. They should prepare them first and be wise in their questions” (Patient 4). Without proper preparation, multiple patients questioned the psychological consequences of goals-of-care discussions on patients: “If his [a hypothetical patient] literacy and educational level were low, then having it [goals-of-care discussions] with him might kill him” (Patient 7).

Discussion

Main findings

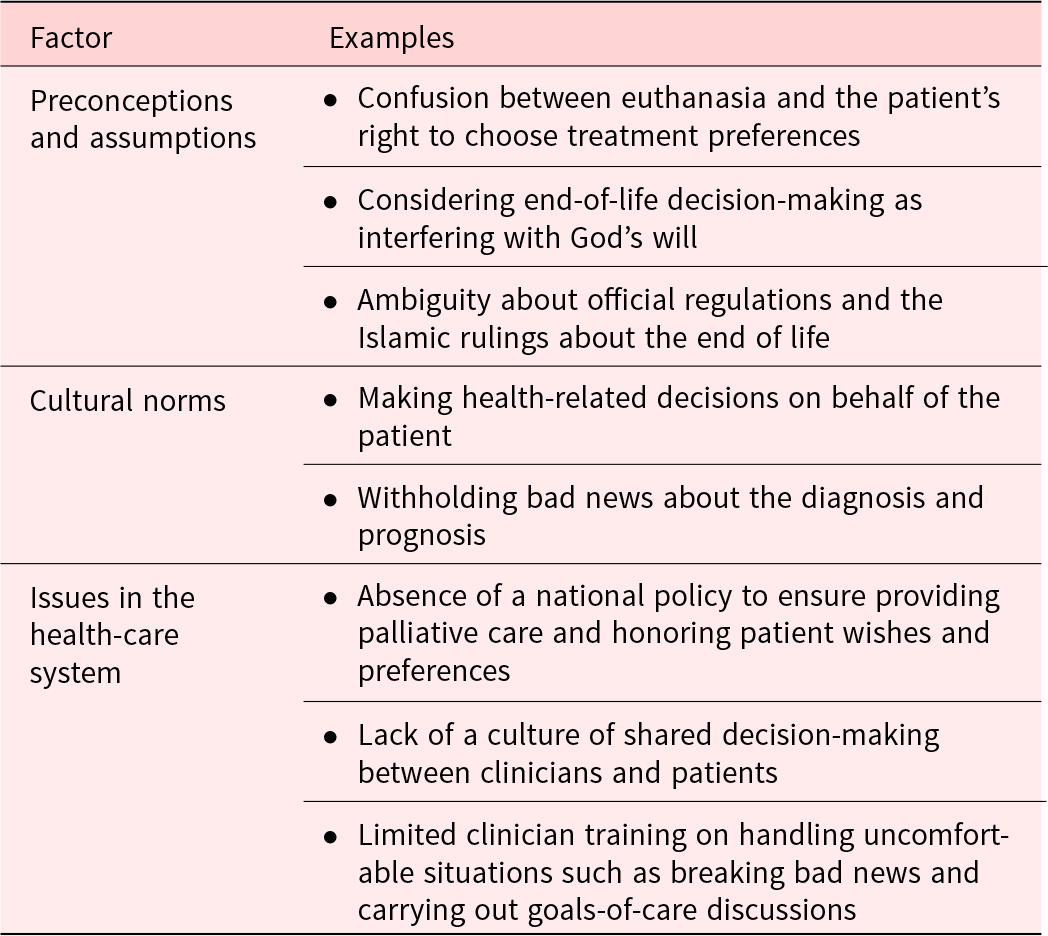

This study’s purpose is to contribute knowledge about the viewpoints about EOL decision-making and goals-of-care discussions among seriously ill adults in Jordan. Through this qualitative descriptive exploration, we have uncovered 4 themes: experiences of suffering, attitudes toward EOL decision-making, goals of care and preferences for EOL, and actions to enhance EOL decision-making. Our findings suggest that EOL decision-making is complex due to factors summarized in Table 4. To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative inquiry to address the phenomena at hand in Jordan and other Middle Eastern countries.

Table 4. Factors influencing goals-of-care discussions and end-of-life decision-making in Jordan

Suffering from serious illness

Our findings suggest that patients experience various kinds of suffering including disease- and treatment-related burdens, inadequately managed symptoms, and psychological distress due to guilt and afraid feelings. Although the finding that patients experienced suffering near EOL is not unsurprising, the diversity of factors patients described in the present study is consistent with other studies about the concept of suffering set in Western countries and other cultures (O’Connor et al. Reference O’Connor, Watts and Kilburn2020; Renz et al. Reference Renz, Reichmuth and Bueche2017). This points to the fact that addressing suffering near EOL is still a necessity, regardless of culture (Busolo and Woodgate Reference Busolo and Woodgate2015).

EOL decision-making is taboo in Jordan

Participants indicated that most Jordanians, patients and clinicians alike, would consider EOL decision-making taboo; thus, they would be hesitant to engage in EOL conversations. These findings are consistent with many studies from countries around the world (Geerse et al. Reference Geerse, Lamas and Sanders2019; Knop et al. Reference Knop, Dust and Kasdorf2022), confirming the role of sociocultural norms as well as assumptions about faith and religion in EOL decision-making (Chakraborty et al. Reference Chakraborty, El-Jawahri and Litzow2017; Clemm et al. Reference Clemm, Jox and Borasio2015). These faith-related and religious assumptions may not necessarily be well grounded. For instance, there exist Islamic Sharia laws for withholding and withdrawing futile treatments, such as Fatwa No. 117 by the Jordan Board of Iftaa’ (2006): “It is permissible not to place a cancer patient on life support equipment, or a respirator, or dialysis machine if the treating team has confirmed and is absolutely certain that such procedures are hopeless. This is provided that this decision is backed by a report of an expert medical team comprising from three specialized, honorable, and trustworthy doctors, at least.” More recently, the Jordan Board of Iftaa’ (2019) made Fatwa No. 3539 stating that “it is permissible for the patient-if conscious-to sign a certain form in which he requests not performing CPR on him in case of cardiac arrest. But, in case the patient is conscious, his close relatives are permitted to recommend not performing CPR on him if trustworthy doctors confirm that such procedure is hopeless.” These Fatwas are consistent with Islamic Sharia laws applied in culturally similar Arab countries such as Saudi Arabia (Woodman et al. Reference Woodman, Waheed and Rasheed2022). Considering these Islamic Sharia laws, patients are allowed to participate in EOL decision-making and request withholding or withdrawing futile treatments under certain conditions (Malek et al. Reference Malek, Abdul Rahman and Hasan2018). Nevertheless, patients in the present study expressed assumptions inconsistent with these Islamic Sharia laws, which indicates a lack of knowledge about existing laws and suggests a need for raising public awareness about Islamic Sharia pertaining to EOL decision-making (Othman et al. Reference Othman, Khalaf and Zeilani2021; Seymour Reference Seymour2018).

Patient autonomy and self-determination

Our findings underscore concerns about the human rights of patient autonomy and self-determination (Cohen and Ezer Reference Cohen and Ezer2013), both of which are violated when EOL decisions are made without patient involvement (Dutta et al. Reference Dutta, Lall and Patinadan2020; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Butow and Kerridge2018). Attention to this matter is warranted at research, clinical, and policy levels. At the practice level, clinicians need to be equipped with essential skills for breaking bad news and carrying out EOL conversations (Bar-Sela et al. Reference Bar-Sela, Schultz and Elshamy2019b; Tulsky et al. Reference Tulsky, Beach and Butow2017). At the broader level, health-care leaders and policymakers need to agree about the nature of EOL decision-making in Jordan (Osman and Yamout Reference Osman, Yamout, Al-Shamsi, Abu-Gheida and Iqbal2022).

Strengths and limitations

Due to a lack of evidence about the population of the seriously ill as well as the status of EOL decision-making in Jordan and culturally similar Arab countries, the comparison of our findings in similar populations is limited. Previous studies highlighted the importance of addressing issues faced by the seriously ill in Jordan to develop practice regulations to improve the quality of care provided to those patients (Abdel-Razeq et al. Reference Abdel-Razeq, Attiga and Mansour2015). Our findings should serve as both a call for more attention to this seriously ill population and a baseline for EOL decision-making practice and policy, not only in Jordan but also in other culturally similar Arab countries to enhance the care provided to similar populations.

The present study has limitations worth highlighting. First, there was selection bias in the study population, given that the patients in this study were healthier than other seriously ill patients who were too sick to participate. Understanding the perceptions and perspectives of the very sick individuals could have added value to the study findings. Second, this study involved 14 patients, which may be perceived as a small sample. We handled these limitations by using purposeful sampling with maximum variation that allowed maximizing the likelihood that the findings reflected various perspectives. Finally, reaching out to the interviewees past the interview time for member checking was difficult; however, peer debriefing provided an opportunity to engage in acknowledgment and bracketing of biases during data analysis and interpretation (Lincoln and Guba Reference Lincoln and Guba1985).

Conclusions

As the first study to address experiences during goals-of-care discussions and perspectives of EOL decision-making in Jordan, whose population is culturally similar to those in over 20 Arab countries, this work contributes to the theoretical development in this research area. By involving seriously ill patients and providing perspectives about their experiences during goals-of-care discussions and attitudes toward EOL decision-making, the findings from this study suggest that it is critical for health-care and religious leaders to discuss culturally appropriate decision-making. The patients in this study emphasized that EOL decision-making is taboo; hence, our study presents novel contributions by encouraging future work to further address culturally sensitive topics like death, dying, and bereavement. Although patients described various factors influencing their attitudes toward decision-making, attention is warranted regarding actions that patients considered crucial for decision-making in Jordan. To enhance the care delivered to seriously ill patients in Arab populations, health-care and religious stakeholders are encouraged to consider the needed actions for appropriate and culturally sensitive implementation of EOL decision-making. Further research should involve the perspective of caregivers, clinicians, and religious leaders and explore how best to improve palliative care and implement EOL decision-making in Jordan and culturally similar countries.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the study patients for their valuable contributions, the clinicians from the participating sites who made recruitment possible, and the University of Iowa Stanley Graduate Award for International Research for funding this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Iowa (No. 201904790) and the 2 study settings (Nos. 13/3/1155 and 19-KHCC-46).