Introduction

Cancer is a common health issue in Latin America, being the second cause of mortality in most of the region and causing 19% of all deaths. In this region, cancer mortality burden is considerable since its presentation often occurs at more advanced stages in a context of poor access to cancer care (Goss et al. Reference Goss, Lee and Badovinac-Crnjevic2013), leaving patients and their families exposed to a poor quality of life (QOL) and impoverishment due catastrophic expenditure (Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance 2020). Although Latin America has achieved important advances in Palliative Care (PC), there is still a considerable gap in PC access and coverage (Pastrana and De Lima Reference Pastrana and De Lima2022). Regarding to Chile, in a recent report describing the gaps in PC access, there has been a progress in access to PC for cancer patients with a coverage of 93%, but this coverage focuses mainly on pain management with little coverage for non-pain symptoms (Pérez-Cruz et al. Reference Pérez-Cruz, Undurraga and Arreola-Ornelas2023). This scenario may be even more challenging for PC planning because of delayed cancer diagnosis due the COVID-19 pandemic (Ward et al. Reference Ward, Walbaum and Walbaum2021).

Patients with advanced cancer experience symptoms and functional decline throughout the course of their disease, particularly during end of life (EOL), requiring support to perform self-care activities (Pérez-Cruz et al. Reference Pérez-Cruz, Shamieh and Paiva2018). Caregivers of cancer patients are usually family members or friends who provide uncompensated care to a patient, helping with daily living activities – such as bathing, feeding, or mobilization, in performing nursing tasks – such as administration of medications or treatment monitoring, and in providing emotional support when required, among others (Ahn et al. Reference Ahn, Romo and Campbell2020; Deshields et al. Reference Deshields, Rihanek and Potter2012; Frambes et al. Reference Frambes, Given and Lehto2018; Ge and Mordiffi Reference Ge and Mordiffi2017; Given et al. Reference Given, Given and Sherwood2012; van Ryn et al. Reference van Ryn, Sanders and Kahn2011). As their primary source of support, family caregivers (FCs) are also exposed to several other strains, such as rearrangement of functions and roles within the household and dealing with work issues and with own personal emotions (Applebaum and Breitbart Reference Applebaum and Breitbart2013; Lund et al. Reference Lund, Ross and Petersen2015; van Roij et al. Reference van Roij, Brom and Youssef-El Soud2019).

Addressing FCs’ burden must consider a very broad perspective using subjective and objective aspects. Subjective burden has been conceptualized as the perceived physical, emotional, social, and financial distress as a result of caring for a person with a serious disease (Choi and Seo Reference Choi and Seo2019; Given et al. Reference Given, Wyatt and Given2004; Nijboer et al. Reference Nijboer, Tempelaar and Sanderman1998; Zarit et al. Reference Zarit, Reever and Bach-Peterson1980), whereas objective burden refers to the amount of time spent on caregiving and the number of tasks that are performed (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Heffernan and Tan2020; Montgomery et al. Reference Montgomery, Gonyea and Hooyman1985; Sales Reference Sales2003). To our knowledge, few publications have described in Latino communities the objective and subjective burden of care that FCs experience while caring for advanced cancer patients. Also, limited reports have described simultaneously how caregiver and patient characteristics jointly influence caregiver burden experience.

Since intensity of stressors vary across different ethnic and cultural groups (Pinquart and Sörensen Reference Pinquart and Sörensen2005), among Latino’s cultural values, familism must be considered (Balbim et al. Reference Balbim, Marques, Cortez, Magallanes, Rocha and Marquez2019). Indeed, this value may increase FC distress according to the perceived family duties when caregiving difficulties arise (Anthony et al. Reference Anthony, John Geldhof and Mendez-Luck2016). As familism can be associated with strong feelings of reciprocity and loyalty among members of the same family, it is possible that caregiving burden could be underperceived by FCs (Gelman Reference Gelman2014). Therefore, it seems relevant to better understand the caregiving phenomenon among Latinos to describe the frequency of perceived burden related to these tasks and to identify specific factors associated with it.

The aims of this study are to describe the caregiving phenomenon in a population of FCs of advanced cancer patients in a Latino community and to identify patient and caregiver factors associated with subjective burden.

Methods

Participants

This cross-sectional observational study analyzes baseline characteristics of FCs enrolled in a longitudinal study that aimed to analyze the association between patient-reported QOL during the last month of life and caregiver perception of quality of EOL. Briefly, advanced cancer patients in PC and their FCs were enrolled at a public hospital in Santiago, Chile, between January 2016 and January 2017. Inclusion criteria included being 18 years old or older, had an adult FC identified, not having delirium, and a Karnofsky Performance Status ≤80. After consent, patients and their FCs completed a baseline questionnaire and were followed-up every 2 weeks until patients’ death. A research nurse trained in PC was responsible of performing the phone surveys to assess patients and caregivers longitudinally.

Measures

Baseline assessments included demographic information such as age, gender, marital status, education, and religion of both patients and FCs. In addition, we included the following validated measures in Spanish: the abbreviated Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale (Breinbauer et al. Reference Breinbauer, Vasquez and Mayanz2009), the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) (Carvajal et al. Reference Carvajal, Centeno and Watson2011), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Villoria and Lara Reference Villoria and Lara2018), and the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL (Suarez-del-Real et al. Reference Suarez-del-Real, Allende-Perez and Alferez-Mancera2011). Data about financial distress, spirituality, and religiosity were collected from patients, whereas FCs were asked to complete single-item questions describing the tasks and activities they performed to characterize the phenomenon of caring.

Zarit caregiver burden scale

The abbreviated Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale was employed to assess the level of subjective caregiver burden. It consists of a 7-item questionnaire in which FCs are asked to rate in a 5-item Likert scale (Never, rarely, sometimes, often, and always) how much burden was perceived for different tasks. Scores range between 7 and 35 points, with higher scores meaning higher subjective burden. This instrument was validated in a Chilean population of outpatient FCs. It showed an internal consistency of 0.84 and defined a cutoff of 17 points to consider the FC as experiencing high-intensity burden (Breinbauer et al. Reference Breinbauer, Vasquez and Mayanz2009). This cutoff was defined using an receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and was similar to the cutoff obtained in a Spanish validation of the instrument (Regueiro Martínez et al. Reference Regueiro Martínez, Perez-Vazquez and Gómara Villabona2007).

Edmonton symptom assessment scale

A Spanish version of the ESAS was employed to examine the average intensity of 10 symptoms in advanced cancer patients over the past 24 hours. Each of these symptoms is rated from 0 (no symptoms) to 10 (worst intensity) on a numerical scale (Carvajal et al. Reference Carvajal, Centeno and Watson2011).

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

Psychological distress was measured using the Spanish version of the HADS (Villoria and Lara Reference Villoria and Lara2018). This 14-item instrument consists of 2 subscales, one for depression and one for anxiety. A score of 8 or higher is considered clinically meaningful for each one of them. The HADS has been previously validated in Spanish, and the internal consistency was reported as 0.75 (Cronbach’s alpha).

Financial distress (FD) and spiritual pain (SP) were assessed with single-item questions in which patients reported intensity of FD or SP in a 0 to 10 scale, with 0 meaning that patient had no FD or SP and with 10 meaning that the patient had the worst possible FD or SP. Objective burden of care was assessed by single-item questions that were asked to the FC and included “have you taken care of the patient for at least one year?,” “do you live with the patient?,” “do you take care of the patient every day?,” “how many hours per day do you take care of the patient?,” “do you also hold a full-time/part-time job?,” “do you share caregiving responsibilities with someone else?,” and “have you ever had any type of training in caring for people with cancer?.”

Statistical considerations

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize our data. For continuous variables, we reported sample size, mean, and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables and median and interquartile range for non-normally distributed variables. For categorical and binary variables, frequency and percentage were reported. Univariate analysis was performed using the abbreviated Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale as the primary outcome. We explored the association between each of the variables with subjective burden, variable that was dichotomized into 2 categories: FCs with intense subjective burden versus FCs without intense subjective burden. T-test, Wilcoxon rank sum test, or chi-square test were used as required. We then performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis to assess the effect of categorical and continuous covariates on subjective caregiver burden intensity, adjusting for possible confounders. For the multivariate analysis, we considered all patient and caregiver variables that were significantly associated with intense subjective burden of care in the univariate analysis, except for patient-reported symptom intensity due to the high correlation between caregiver and patient-reported symptom intensity. It is important to highlight that all variables included in the multivariate model, theoretically, could influence the experience of subjective burden. For example, it has been reported that spirituality, as a proxy of religion, is associated with caregiver burden in caregivers of chronic conditions (Anum and Dasti Reference Anum and Dasti2016).

Then, we proposed a model to predict intense subjective caregiving burden, using backward and forward selection strategies, with the whole model using both 0.05 and 0.1 cutoffs to create a new simpler model. Using likelihood ratio (LR) test, we then assessed whether the final model was nested under the larger original model. Finally, we estimated sensitivity, specificity, and discriminatory capacity of the final model using the ROC curve. All computations were carried out in a standard software package (Stata, version 12.0; StataCorp).

Data protection and confidentiality

The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Comité Ético Científico – Facultad de Medicina, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Protocol Number 13-154). All participants provided signed informed consent. Health information was protected, and data confidentiality was maintained throughout the study. Only trained personnel in maintaining confidentiality and the Primary Investigator had access to study records.

Results

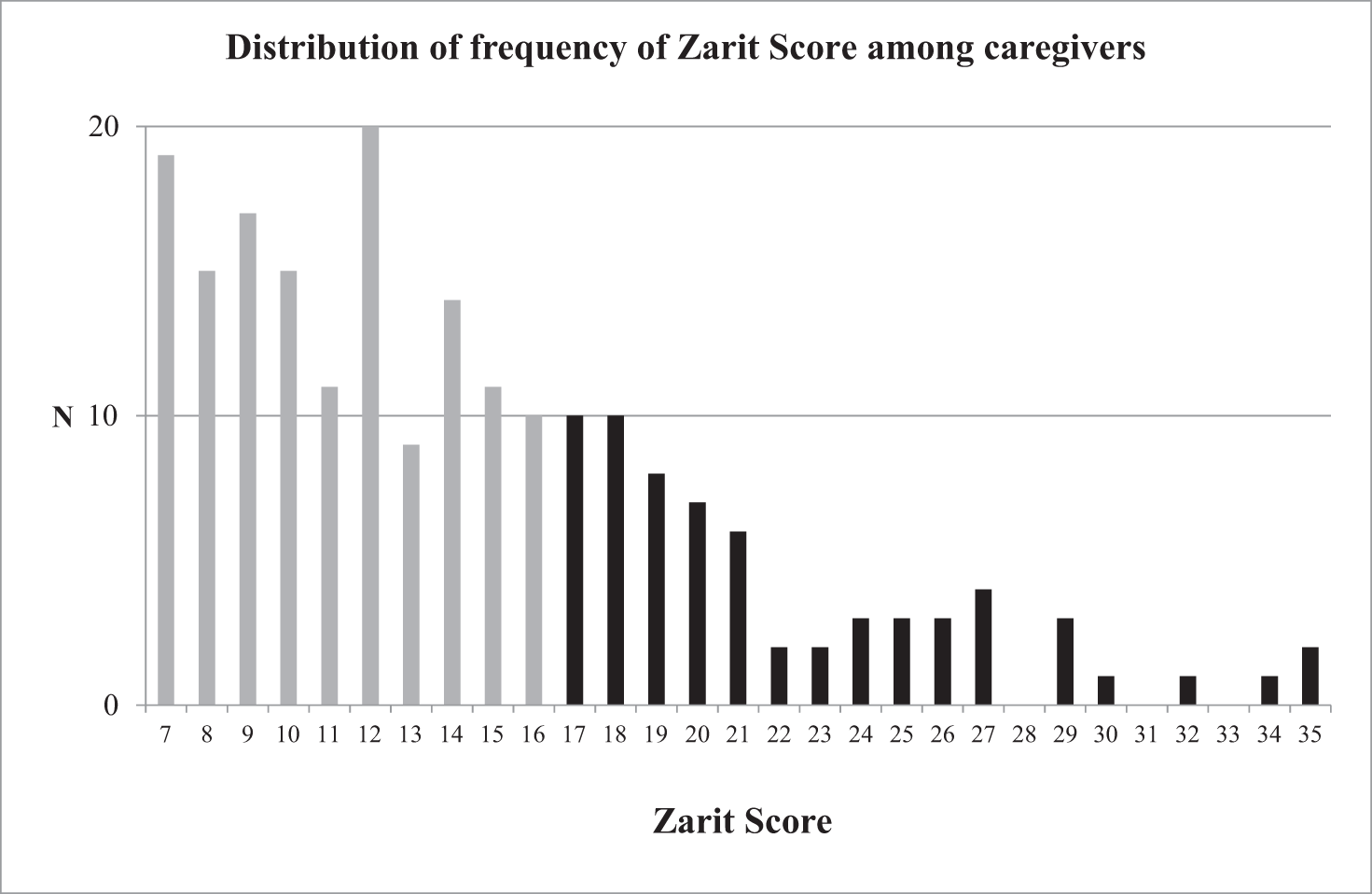

A total of 207 advanced cancer patients in PC and their FCs were included. Caregiver and patient demographics are described in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The mean age of FCs was 50 years, and 78% were women. The most common relationships with the patients were being the spouse (36%) or children (39%). Sixty-six out of 207 (32%) FCs reported high-intensity subjective burden of care. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the abbreviated Zarit Scale scores. Regarding questions assessing objective burden of care, we found that 82% of the FCs take care of the patient daily, with a mean of 14.5 hours per day (SD = 8.8). Eighty percent of FCs live with the patient in the same household, 53% of FCs have taken care of the patients for 1 year or more, and 49% of the FCs also hold a full-time/part-time job. Finally, 31% of the FCs take care of the patients alone, without any help, and 78% have not had training in caregiving.

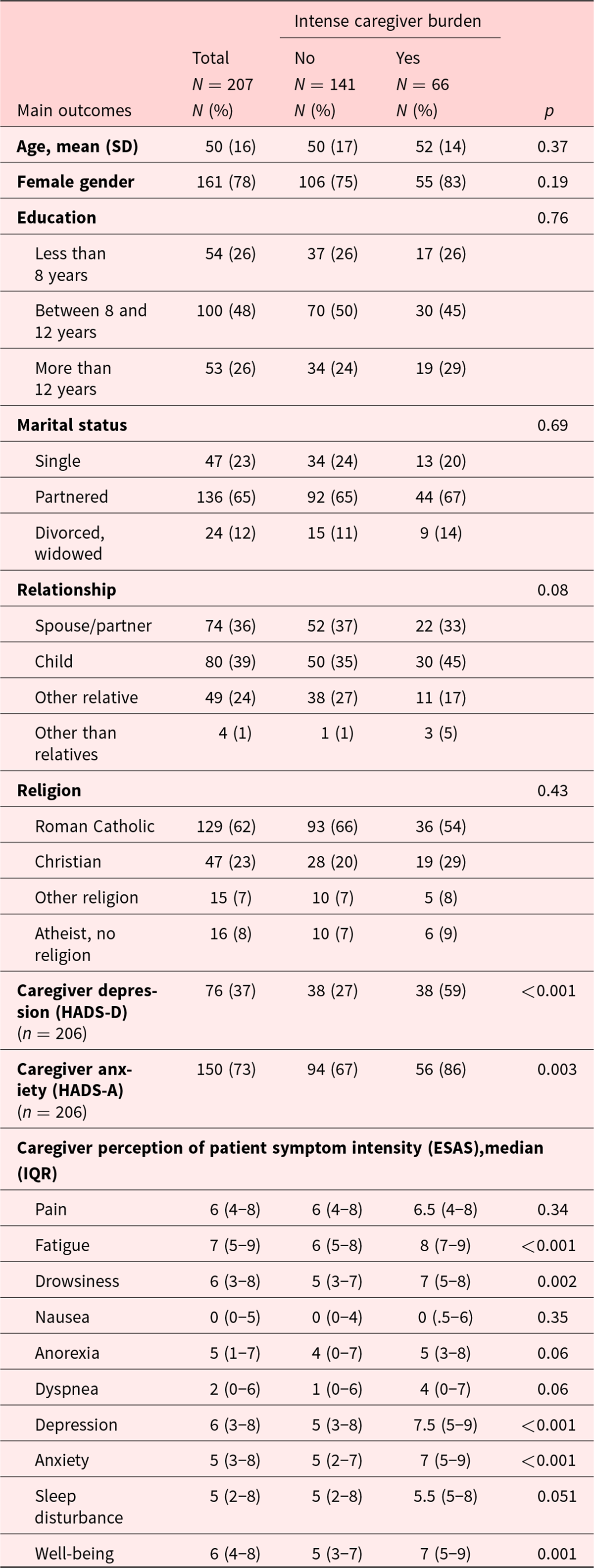

Table 1. Caregiver demographics and univariate analysis by caregiver burden

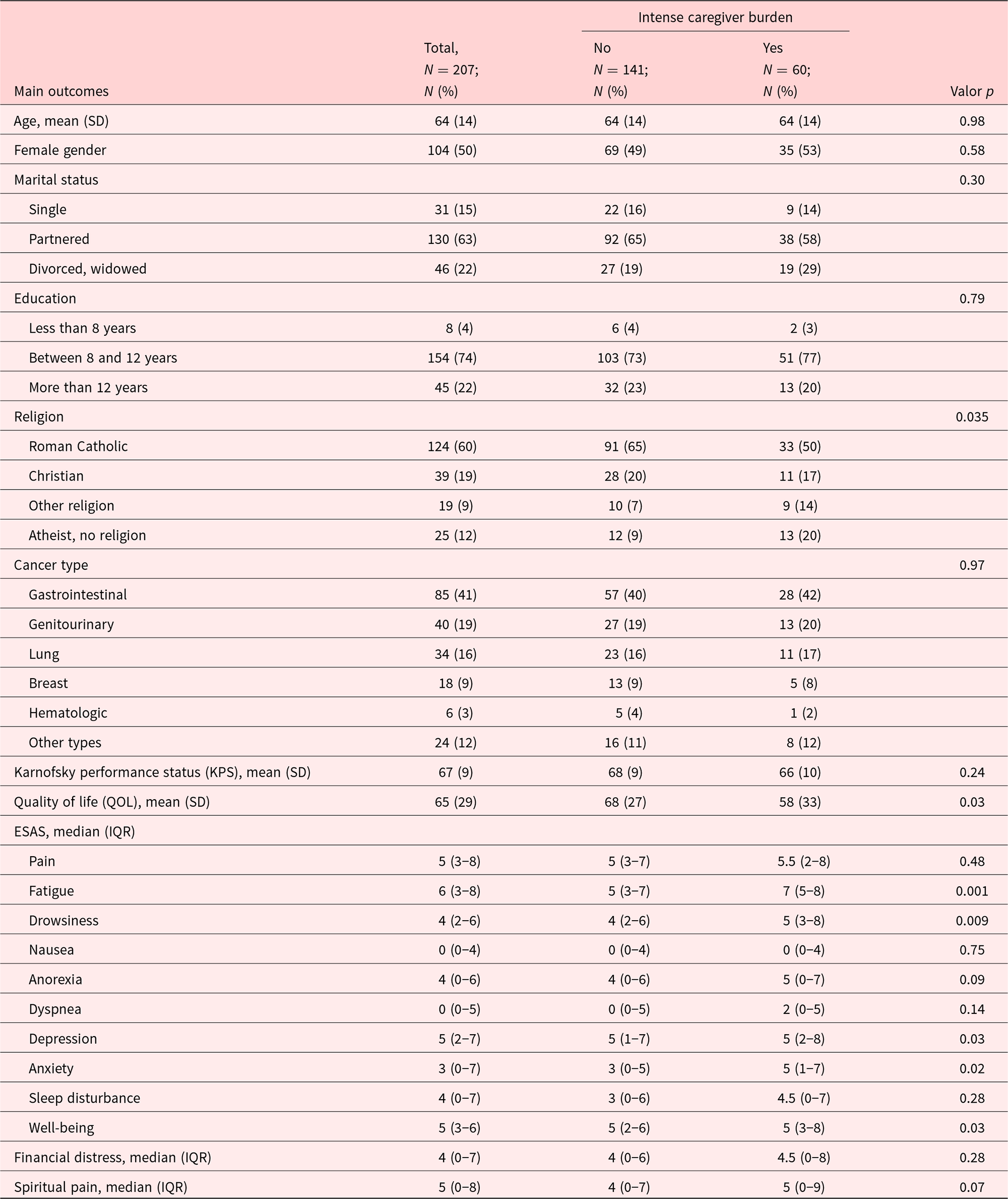

Table 2. Patient demographics and univariate analysis by caregiver burden

Figure 1. Frequency of Abbreviated Zarit Scores among caregivers. Scores considered as high-intensity caregiver burden (score 17 or more) as shown in black.

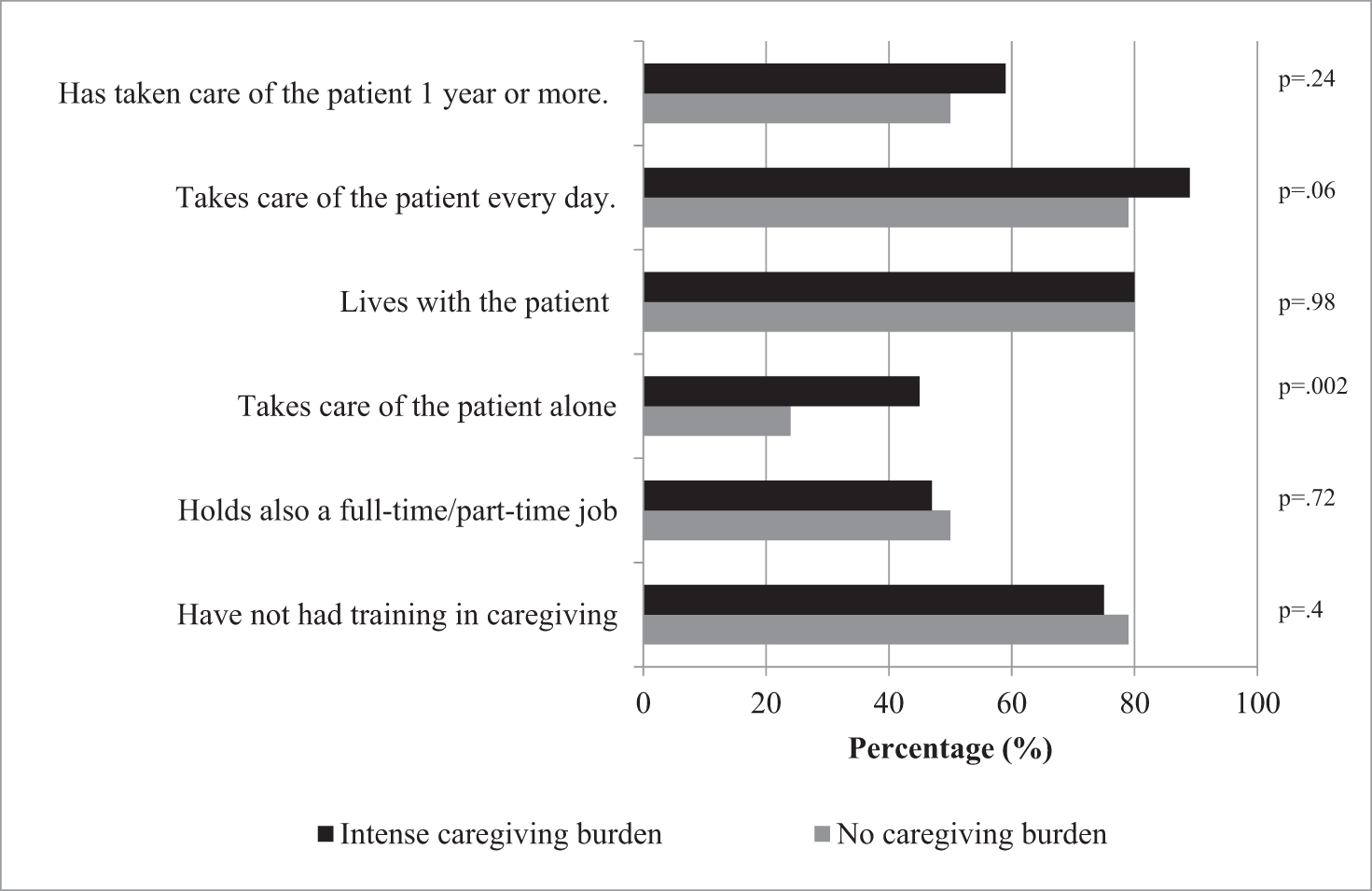

In the univariate analysis between caregiver burden with FCs’ characteristics, high-intensity subjective burden of care was associated with caregiver depression (59% vs. 27%, p < 0.001) and anxiety (86% vs. 67%, p = 0.003). Also, subjective burden of care was significantly associated with FCs’ higher perception of patient fatigue, drowsiness, depression, anxiety, and poor well-being (Table 1). Regarding patients’ characteristics, high-intensity subjective burden of care was significantly associated with patient-reported religion and lower patient-reported QOL (Table 2). Although not statistically significant, there was a trend between high-intensity subjective burden of care and patient-reported SP. Intense subjective burden was also associated with patient-reported fatigue, drowsiness, anxiety, depression, and poor well-being. Intense burden was also more frequent among FCs who took care of the patient without help (45% vs. 24%, p = 0.002) and a trend among FCs who take care of the patient daily (89% vs. 79%, p = 0.06) but was not associated with other variables reporting objective burden of care (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Differences in objective burden between caregivers with and without intense caregiving burden.

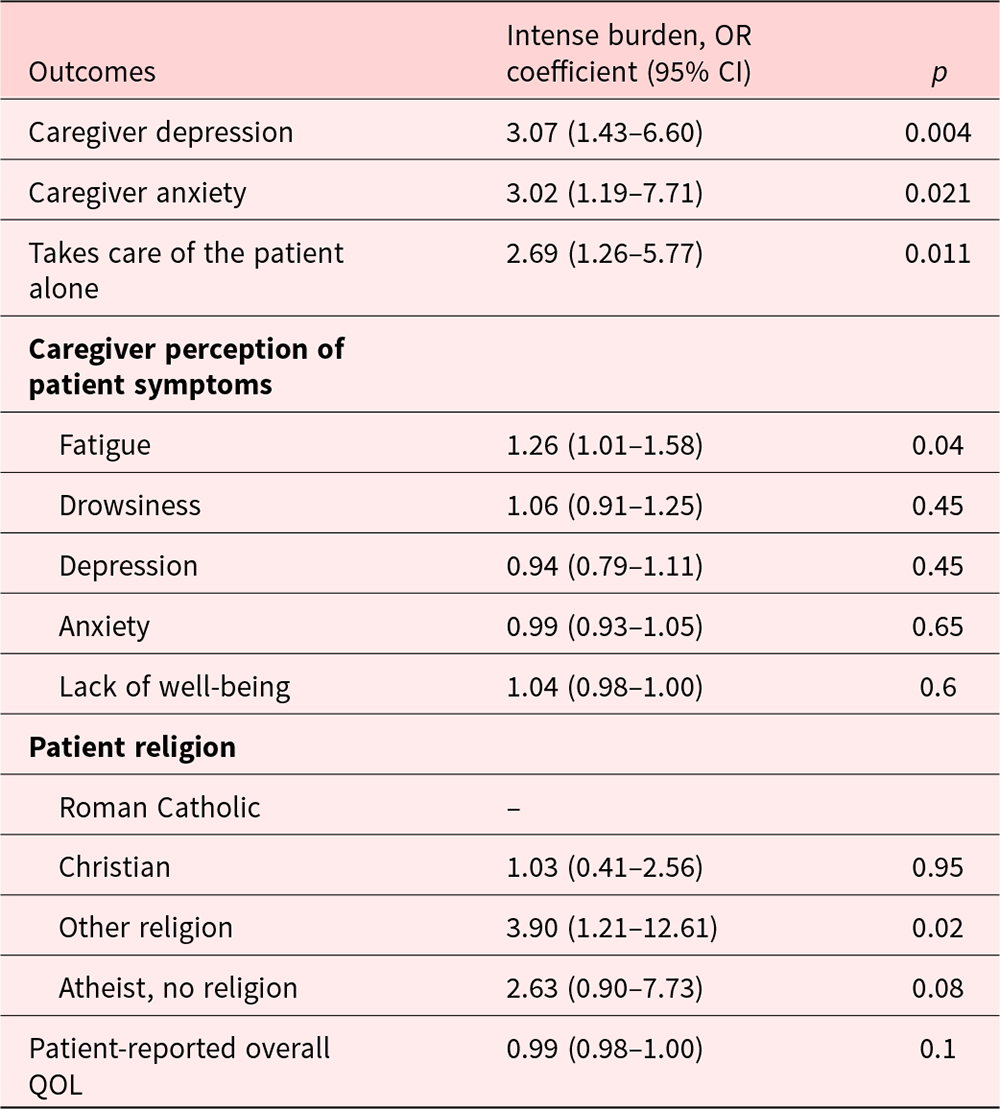

In the multivariate analysis, we found that caregiver depression (p = 0.004, odds ratio [OR] = 3.07, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.43–6.60), caregiver anxiety (p = 0.021, OR = 3.02, 95% CI = 1.19–7.71), taking care of the patient alone (p = 0.011, OR = 2.69, 95% CI = 1.26–5.77), caregiver perception of patient’s fatigue (p = 0.04, OR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.01–1.58), and having a religion other than Christian or being atheist (p = 0.02, OR = 3.90, 95% CI = 1.21–12.61) remained independently associated with high subjective caregiver burden (Table 3). To create a simpler model, we performed both backward and forward selection strategies and different cutoffs as described in the Methods section. Using the different strategies, we identified a final model that included 4 variables. We found that caregivers with depression had 2.45 odds of reporting high subjective burden than caregivers without depression (p = 0.011, 95% CI = 1.23–4.90) and that caregivers with anxiety had 2.49 odds of reporting high subjective burden compared with those without anxiety (p = 0.04, 95% CI = 1.04–5.93). We also found that caregivers who took care of the patient alone had 2.73 odds of reporting high subjective burden than those who had help (p = 0.005, 95% CI = 1.35–5.55). Finally, we found that the odds of high subjective burden among caregivers increased 1.31 times per each 1 point increase in caregivers perception of patient fatigue (p = 0.001, 95% CI = 1.13–1.53). Using the LR test, we found that a simpler model was nested under the larger model (LR test χ 2 = 11.89; p = 0.16), suggesting that the final model is more parsimonious and therefore better.

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of caregiver and patient characteristics by caregiver burden

To estimate the usefulness of this model, we estimated its sensitivity and the specificity to predict intense caregiving burden. The sensitivity of the model was 48% (31/65), and the specificity was 90% (126/140). The positive predictive value was 69% (31/45), and the negative predictive value was 79% (126/160). The area under the ROC curve was 0.78, indicating that the model had a good discrimination capacity.

Discussion

This study reveals that FCs of advanced cancer patients from a Latino community experienced high-intensity subjective burden, which is associated with increased objective burden, such as taking care of the patient alone, as well with caregiver psychological distress and caregiver perceived patient fatigue. This finding adds to current literature, demonstrating that caregiver burden intensity is not only associated with caregiver psychological distress but also independently associated with objective measures of caregiving burden, highlighting the relevance of these 2 components in the experience of FCs (Fekete et al. Reference Fekete, Tough and Siegrist2017; Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Black and Albert2014). Our proposed model has good discriminatory capacity and has a high specificity, allowing the model to identify FCs with lower probability of high-intensity subjective burden in a high-risk population. To our knowledge, this study is the first to find these associations in an advanced cancer population in Latin America.

In our study, most of FCs are female and first-degree relatives, similar to what has been described elsewhere (Ahn et al. Reference Ahn, Romo and Campbell2020; Al-Daken and Ahmad Reference Al-Daken and Ahmad2018; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Liao and Shun2018; Tan et al. Reference Tan, Molassiotis and Lloyd-Williams2018). Prevalence of burden observed in this study is also consistent with previous global evidence showing that the proportion of FCs who reported high levels of subjective burden varied from 35% to 56% (Costa-Requena et al. Reference Costa-Requena, Espinosa Val and Cristofol2015; Mirsoleymani et al. Reference Mirsoleymani, Rohani and Matbouei2017; Palacio et al. Reference Palacio, Krikorian and Limonero2018; Palacios et al. Reference Palacios, Perez and Webb2020; Palma et al. Reference Palma, Simonetti and Franchelli2012; Perpina-Galvan et al. Reference Perpina-Galvan, Orts-Beneito and Fernandez-Alcantara2019). These results confirm that this population share a common experience with FCs around the world.

We also report that a large proportion of FCs experience a considerable objective burden of care, including an extended period taking care of the patient, taking care of their loved ones in a daily basis and with lengthy daily schedules, and most of them actually living with the patient. Interestingly, we find that objective burden is higher among FCs who did not have someone to share caregiving responsibilities with, and this association remains significant in the multivariate analysis. This finding is related with a report by Park and colleagues who observed in a Korean population that FCs of cancer patients who shared caring responsibilities were less likely to experience the negative aspects of caregiving (Park et al. Reference Park, Shin and Choi2012). We also observe a nonsignificant trend in the univariate analysis, showing that providing care during a considerable number of hours – suggesting a high level of caregiver engagement – could also influence caregiving burden experience (Hsu et al. Reference Hsu, Loscalzo and Ramani2014; Unsar et al. Reference Unsar, Erol and Ozdemir2021; Yoon et al. Reference Yoon, Kim and Jung2014).

The proportion of FCs reporting a considerable objective burden of care reflects that this is a homogeneous population, which may have challenged our ability to find other associations between high subjective burden of care and other objective burden variables. These results together suggest that it is likely that intense caregiving burden is underreported in this population, as only a third of FCs are categorized as experiencing high-intensity burden, although individual variables related to objective burden are much more frequent. Latinos have strong family relationships in which providing care to both healthy and sick relatives is considered a part of it. Reporting caring as burden could be seen as not loving their family member or could also being experienced as guilt (Aranda and Knight Reference Aranda and Knight1997; Depp et al. Reference Depp, Sorocco and Kasl-Godley2005; Parveen et al. Reference Parveen, Morrison and Robinson2014). Studies on Chinese population also show the protective factor of filial piety against the level of subjective burden (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Kim and Dong2019; Lai Reference Lai2007, Reference Lai2010). Another hypothesis could be that other factors besides objective burden could influence the experience of care. Literature from dementia patients suggests that the caregiving experience, whether it is perceived as a burden or not, is influenced not only by “objective” factors such as patient symptoms or the intensity of the caregiving demands. Caregiving was also influenced by more qualitative factors such as the quality of prior relations, the meaning attributed to caring, and the experience of reward in taking care of a loved one (Palacios et al. Reference Palacios, Perez and Webb2020). Literature among FCs of cancer patients addressing this phenomenon should be studied in the future.

Another concerning finding in this study is that most FCs have not had training in caregiving skills. This shows that FCs are disregarded by the health-care system (Ackerman and Sheaffer Reference Ackerman and Sheaffer2018; Schulz et al. Reference Schulz, Beach, Czaja, Martire and Monin2020) even when they are a cardinal part in it. Besides experiencing objective burden, this population does not have support in improving their abilities to take care of their loved ones exposing them. Interventions in caregiving skills, social support, or respite care could be possible alternatives to support this vulnerable group (Grant et al. Reference Grant, Sun and Fujinami2013; McPherson et al. Reference McPherson, Wilson and Lobchuk2008; Nissen et al. Reference Nissen, Trevino and Lange2016).

FCs with symptoms of anxiety and depression are more likely to report a high-intensity subjective burden of care. Similar findings were noted in several previous studies (Costa-Requena et al. Reference Costa-Requena, Espinosa Val and Cristofol2015; Perpina-Galvan et al. Reference Perpina-Galvan, Orts-Beneito and Fernandez-Alcantara2019; Tan et al. Reference Tan, Molassiotis and Lloyd-Williams2018; Unsar et al. Reference Unsar, Erol and Ozdemir2021); only one publication has reported this finding in people from Latin America (Palacio et al. Reference Palacio, Krikorian and Limonero2018). It is well known that cancer is a highly stressful event, which may constitute a traumatic stressor for many people including family members. Therefore, psychological problems in FCs of advanced cancer patients, such as depression and anxiety, could be increased due to high intensity of care needs and a dramatically increased use of formal services at EOL (Abbasi et al. Reference Abbasi, Mirhosseini and Basirinezhad2020; Brazil et al. Reference Brazil, Bedard and Willison2003; Garcia-Torres et al. Reference Garcia-Torres, Jablonski and Solis2020; Unsar et al. Reference Unsar, Erol and Ozdemir2021).

Patient symptoms such as fatigue, drowsiness, depression, anxiety, and poor well-being and caregiver perception of those symptoms are also associated with high subjective caregiver burden. This is in line with findings from previous studies (Krug et al. Reference Krug, Miksch and Peters-Klimm2016; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Liao and Shun2018; Passik and Kirsh Reference Passik and Kirsh2005; Peters et al. Reference Peters, Goedendorp and Verhagen2015; Utne et al. Reference Utne, Miaskowski and Paul2013). In PC, it is common that patients experience various physical and psychological symptoms (Dumitrescu et al. Reference Dumitrescu, van den Heuvel-olaroiu and van den Heuvel2007; Kang et al. Reference Kang, Kwon and Hui2013). Therefore, FCs who assume the task of interpreting and monitoring patient’s status reported a considerable burden. High levels of burden is associated with FCs whose patients reported poor QOL. This finding contrasts with a German study by Krug and colleagues in which caregiving burden was not associated with a decrease in patient QOL (Krug et al. Reference Krug, Miksch and Peters-Klimm2016). It is known that QOL of advanced cancer patients is directly related to the number of symptoms and the possibility of improving symptom control (Dumitrescu et al. Reference Dumitrescu, van den Heuvel-olaroiu and van den Heuvel2007; Kang et al. Reference Kang, Kwon and Hui2013). It is possible to hypothesize that burden of care increases as FCs realize that regardless of the activities performed, none of them improves QOL of their patients during the EOL. Some authors indicate the importance of understanding reciprocal suffering in the caregiver–patient relationship (Wittenberg-Lyles et al. Reference Wittenberg-Lyles, Demiris and Oliver2011). This supports the idea that all efforts of PC teams should focus on the dyad rather than the patient or caregiver separately.

One novel aspect of this study is the proposal of a model to identify FCs with high burden. This model includes the presence of depression, anxiety, taking care of the patient alone, and caregiver perception of patient fatigue. The presence of any or more than one criterion in each caregiver increases their likelihood of experiencing high-intensity burden. As the model has a good specificity, it can be thought of as a diagnostic rather than a screening tool.

All these findings are relevant for Latin American countries as caregiving is usually performed by family members who lack support from public institutions, from the community or other family members, and therefore is commonly underrecognized as a health problem (The World Bank 2011). Highlighting this issue in the region could contribute to increasing awareness of its frequency and impact in this population to reveal its relevance as a health issue in the public discussion and promote the implementation of policies to prevent this experience before burden becomes critical.

Limitations of this study must be noted. First, this study involves secondary data; therefore, the study was not powered to detect associations with specific variables. Of note, the unequal distribution of the sample sizes of the main outcome could have decreased the ability to detect other statistically significant differences. Regardless of this limitation, we were able to detect some difference between the groups, making these findings relevant. Second, the cross-sectional nature of this research does not allow us to suggest causality. However, the exploratory nature of this analysis allows us to generate new hypothesis for future research. Third, all patients recruited to this project were receiving PC in a single public hospital. Thus, our findings should not be generalizable to all Chilean or Latin American population.

In summary, FCs of advanced cancer patients enrolled in a PC unit from a public hospital in Santiago de Chile experience high burden of care frequently, which is independently associated with caregiver anxiety and depression, lack of help with caregiving, an indicator of objective burden, and FCs’ perception of patient fatigue. These findings suggest the need of psychosocial support to FCs to improve mental health outcomes and decrease caregiver burden. It also suggests that strategies should be implemented at the institutional level to better support FCs to prevent or decrease burden of care.

Competing interests

None.