BACKGROUND

The significant psychological, social, and physical impact on family caregivers when providing home-based family caregiving for the terminally ill is well documented (Schulz & Beach, Reference Schulz and Beach1999; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Kristjanson and Currow2005; Grande et al., Reference Grande, Stajduhar and Aoun2009a ; Stajduhar et al., Reference Stajduhar, Funk and Toye2010). Family caregivers' psychological outcomes can be improved if good support is received during caregiving (Ferrario et al., Reference Ferrario, Cardillo and Vicario2004; Grande et al., Reference Grande, Farquhar and Barclay2004; Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, McKenzie and Bloch2006; Grande et al., Reference Grande and Ewing2009b ). Identifying and addressing concerns early on leads to better health outcomes for carers (Grande et al., Reference Grande, Farquhar and Barclay2004; Grande et al., Reference Grande, Stajduhar and Aoun2009a ). However, adequate assessment of family caregivers' support needs by service providers is often informal due to the limited time available when their focus is primarily on the care recipient (Ewing et al., Reference Ewing, Brundle and Payne2013).

Family caregivers of people with a motor neurone disease (MND) often describe their caring experiences as unrelenting due to the progressive nature of the disease and the relative hopelessness with respect to recovery (Locock & Brown, Reference Locock and Brown2010; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Connors and Priddis2012; O'Brien et al., Reference O'Brien, Whitehead and Jack2012). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive neurodegenerative MND with an incidence of 1–2 per 100,000 per year, a peak age at onset in the sixth decade of life, and a median survival of about 3.5 years from onset of symptoms (van Teijlingen et al., Reference van Teijlingen, Friend and Kamal2001; Leigh et al., Reference Leigh, Abrahams and Al-Chalabi2003; Bromberg, Reference Bromberg2008). People with an MND can progress rapidly to high levels of disability over a period of months rather than years, which intensifies their needs for support, including assistance with feeding, communication, movement, toileting, and other tasks of daily living (Oliver & Aoun, Reference Oliver and Aoun2013).

Studies have reported that family caregivers suffer from anxiety, depression, strain, burden, fatigue, impaired quality of life, and reduced social contacts (Hecht et al., Reference Hecht, Graesel and Tigges2003; Chio et al., Reference Chio, Gauthier and Calvo2005; Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Atkins and Landau2006; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Bentley and Funk2013). While management of the physical symptoms in MND is paramount, attending to such family caregivers' psychosocial needs is crucial in order to prevent deterioration in their health outcomes (Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Atkins and Landau2006; Oyebode et al., Reference Oyebode, Smith and Morrison2013). Most individuals with an MND live at home, where their psychosocial functioning is intimately connected to the extent and quality of support they receive from family members. Interventions to reduce caregiver burden and distress related to MND have been reported with varying success (Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Atkins and Landau2006; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Felgoise and Walsh2009; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2014). It is thus important to design and evaluate effective interventions and find ways to deliver them to families living and caring for someone with a motor neurone disease (Pagnini et al., Reference Pagnini, Simmons and Corbo2012; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Bentley and Funk2013; Oliver & Aoun, Reference Oliver and Aoun2013).

However, there is a lack of suitable tools for assessment of family caregivers' support needs during end-of-life home care (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Trauer and Graham2010; Ewing & Grande, Reference Ewing and Grande2013), particularly for the period between diagnosis and end-of-life care (Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Atkins and Landau2006; Oyebode et al., Reference Oyebode, Smith and Morrison2013).

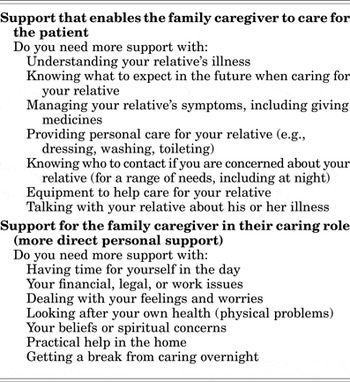

The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) is a validated evidence-based tool used to identify family carer support needs in a systematic way, rather than employing the standard ad-hoc manner. As such, the tool also serves as a supportive carer intervention and, while carer-led, is facilitated by the health professional (Ewing et al., Reference Ewing, Brundle and Payne2013; Ewing & Grande, Reference Ewing and Grande2013). The CSNAT adopts a screening format that is structured around 14 broad support domains. This format allows it to be brief but also comprehensive, enabling caregivers to identify the domains in which they require further support, which can then be discussed with health professionals. Each item represents a core family carer support domain in end-of-life home care, and these domains fall into two distinct groupings: those that enable the family caregiver to care and those that enable more direct support for themselves. There are 4 response options for each of the 14 CSNAT items that allow family caregivers to indicate the extent of their support requirements for each domain: “no more,” “a little more,” “quite a bit more,” or “very much more” (Table 1). The health professional meets with the family caregiver to discuss priority needs and to formulate an action plan (as described in detail in the section on “The Intervention”).

Table 1. Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) domains (Ewing et al., Reference Ewing, Brundle and Payne2013)

The CSNAT has been trialed using a stepped wedge cluster design within Silver Chain (a large community-based service provider in Western Australia) with 322 family caregivers of terminally ill people (mainly with cancer) and 44 nurses. The intervention group experienced a significant reduction in caregiver strain relative to controls (p = 0.018, d = 0.35) (Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Grande. and Howting2015b ), and the feedback from family caregivers (Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Deas and Toye2015a ) and nurses (Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Toye and Deas2015c ) on using the CSNAT was positive. Although the CSNAT appeared to offer a practical approach to assessing and addressing family caregiver needs in cancer, it was deemed important to assess the extent to which the tool could be appropriate for use in other settings and among different disease groups. The present study was thus designed to implement and test the suitability of the CSNAT with family caregivers of people living with MND in the community across the entire spectrum of the caring experience, not only at the end of life.

OBJECTIVE

Our aim was to assess the feasibility and relevance of the CSNAT in home-based care during the caregiving period from the perspectives of the family caregivers of people with MND and their service providers.

METHODS

The study was conducted in Perth (in Western Australia (WA)) from April to July of 2014. It was approved by Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (SONM11-1014). All participants provided written informed consent to participate, and the ethics committee approved this consent procedure.

Study Design

The study was designed to be descriptive and longitudinal. Family caregivers' support priorities were collected through the set of items on the CSNAT. Their feedback was obtained via semi-structured telephone interviews, while care advisors' feedback was gleaned from a self-administered questionnaire with open-ended questions. Feedback from both groups was obtained upon completion of the intervention (as described below). Family caregivers were considered to have concluded the study if they completed two CSNAT contacts with the care advisor (6 to 8 weeks apart).

Participants

The study was conducted with primary family caregivers of clients of the Motor Neurone Disease Association of Western Australia (MNDAWA) and their care advisors. This entity has in its database about 130 clients at various stages of disease progression, and the vast majority of people with MND in WA are registered with the association. All adult caregivers (aged 18 years or older) who were caring at home and were able to read and write in English were eligible for the study, unless care advisors had concerns about a caregiver's ability to cope with research because of exceptionally high levels of distress. A primary family caregiver is defined as a person who, without payment, provides physical (and emotional) care to a person who is expected to die during the course of the period of caring. This care may be provided on a daily or intermittent basis.

The four care advisors working for the association were invited to participate. The standard practice of care advisors is to regularly visit clients at home, and their role involves complex case coordination, provision of disability aids and equipment, and delivery of information and facilitated support programs in order to enable people with MND to live as independently as possible for as long as possible. The care advisors attended a training session with the research team and had weekly contacts with the research officer, in line with previous work (Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Grande. and Howting2015b ).

Participation in the feasibility study was voluntary for both groups, with no undue influence placed upon them. Family caregivers were assured that their decision would not in any way affect the supportive care they were then receiving or any care that they might receive in the future from any agency. Care advisors were also assured that their decision would not in any way affect their employment with the association.

The Intervention

The intervention consisted of the following steps:

-

■ the CSNAT was introduced to the family caregiver by the care advisor;

-

■ the family caregiver was given time to consider which domains they required more support with;

-

■ an assessment conversation took place where the care advisor and family caregiver discussed the domains where more support was needed to clarify the specific needs of the family carer, including what their top priorities were;

-

■ a shared action plan was formulated where the family caregiver was involved in identifying the type of input they would find helpful (rather than delivery of the “standardized” supportive input that the service usually delivers);

-

■ a shared review was planned within 6 to 8 weeks.

Data Collection

The four care advisors working for the MNDAWA, who regularly visit clients at home, introduced the study to the family caregivers who met the inclusion criteria, and they obtained written consent to trial the CSNAT and provide feedback to the researcher at the end of the trial. The care advisors collected the CSNAT data from the caregivers during their usual visits. For the purposes of this feasibility study, there was a baseline visit and then a follow-up visit within 6 to 8 weeks.

The researchers liaised regularly with care advisors during the data collection period to ensure that the research process was followed. They also collected feedback information from family caregivers after they had completed the study. Patient deaths were monitored with care advisors throughout the data collection period to ensure that recently bereaved family carers were not contacted by phone to complete the follow-up interview, which would have been insensitive.

Family caregivers were interviewed by an experienced research nurse, who telephoned at a prearranged time convenient for all (on average, within two weeks of completion of the intervention) to seek their feedback on the appropriateness, relevance, and benefit of the assessment process. Participants were given the opportunity to describe any other benefits or problems and ways of improving their experience of the CSNAT intervention. The questions asked at this phase were (as described in Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Deas and Toye2015a ):

-

■ How easy or difficult was it for you to complete the CSNAT assessment of your support needs?

-

■ Did you feel that completing the assessment process was helpful in getting the support you needed?

-

■ Did this experience of identifying your needs affect what you did yourself?

-

■ Did you feel that your needs as a carer were acknowledged/listened to in a way that was distinct from the needs of the patient?

-

■ Do you think that the CSNAT assessment process could be improved in any way?

Care advisors preferred to give feedback by completing a self-administered questionnaire with open-ended questions in order to: (1) report on their experience with facilitating this process; (2) evaluate the benefits of or barriers to implementing the CSNAT with MND family caregivers; (3) suggest an optimal stage and time for administration and review; and (4) offer suggestions to assist with future planning. Care advisors chose written feedback, as this method gave them time in their busy schedules to consider their answers and return the completed survey when convenient. An anonymous self-administered survey was sent to each care advisor and collected later by the researcher from the MNDAWA office in a sealed envelope.

To get an indication of the disability of the care recipients and thus the burden this might pose for family caregivers, care advisors also completed a standard tool on the functional status of the person with MND using the Revised Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS–R), which has 12 items that assess activities of daily living (ADL) functions and changes in fine motor, gross motor, bulbar, and respiratory function (Cedarbaum et al., Reference Cedarbaum, Stambler and Malta1999). Higher scores are indicative of less impairment.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics, using SPSS software (v. 22), were employed to describe the demographic characteristics of family caregivers and their support needs as identified by the CSNAT. Because of the small numbers involved, those reporting a need were grouped together (from “a little more” to “very much more”). Data from the interviews with caregivers were subjected to thematic analysis (Guest et al., Reference Guest, MacQueen and Namey2012). Initial coding was carried out independently by the first two authors and was supported by NVivo 10 software. The interviews were not audiotaped, but meticulous notetaking allowed for verbatim transcripts. Transcribed interview notes were read and reread to identify keywords and key phrases, which were then grouped into categories labeled with codes. To enhance the credibility of our findings, the interviewer was involved in the analysis process so that consideration of the nonverbal context was assured. The major themes emerged after comparisons within and among individual interviews. These themes were initially identified independently, with differences resolved by discussion and returning to the data when necessary. Exemplars are provided herein to explain themes and describe how interpretations were reached.

The care advisors' written feedback data were subjected to content analysis by the first two authors following the same rigor, with responses grouped according to each survey item, ensuring that the context or explanation could be considered, and establishing overarching categories through comparison of content. Exemplars demonstrate how interpretations were reached (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005). Identified themes highlighted the relevance and feasibility issues for both groups.

RESULTS

Some 30 family caregivers were recruited by 4 care advisors from the MNDAWA, and 24 completed the study during the 4-month period (80% completion rate). Given the progressive nature of the neurological disease in this patient group, four patients died before the family caregiver completed the intervention. In addition, one carer declined due to her husband not wanting her to be involved any longer, and another went on an extended holiday and was not contactable. The final sample size was based on the number of clients visited regularly by the care advisors during the four-month study period and whose family caregivers met the selection criteria and agreed to participate.

Family caregivers completed two CSNAT forms (at a median interval of seven weeks), followed each time by a discussion about their support needs with the care advisors. For the first CSNAT contact, visits were face to face (79%) or by telephone (21%); for the second CSNAT contact, 46% of visits were face to face and 54% by telephone, in keeping with care advisors' usual practice. Feedback interviews by the researcher were undertaken on average 15.9 days after study completion, and interviews lasted an average of 12.4 minutes.

The majority of family caregivers found that the CSNAT form was easy to complete (83.3%), taking a median of 10 minutes (range = 3–20). All caregivers found the questions to be clear and appropriate, and they agreed that the instrument adequately addressed their support needs.

Participants' Characteristics

The majority of family caregivers were female (75%), married (87.5%), and spouses/partners (79.2%), and 54% were retired. Their mean age was 63.8 years (SD = 12.9) (Table 2). People with MND were predominately male (70.8%), with a mean age of 62.8 years (SD = 10.8) and a median time since diagnosis of 20.5 months (range = 4–89). The ALS functional rating scale of fine motor, gross motor, bulbar, and respiratory function measured a median score of 27 (range = 9–46), indicating moderate functional impairment (Table 2).

Table 2. Profile of family caregivers and people with MND (N = 24)

Care advisors were female and had been working in the healthcare field in nursing or physiotherapy for 20 to 35 years and had worked as MND care advisors for 0.5 to 5 years.

Family Caregivers' Support Needs and Provided Solutions

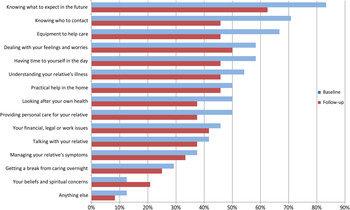

The top five support needs reported by family caregivers consisted of (Figure 1): (1) knowing what to expect in the future (83%); (2) knowing who to contact if concerned (71%); (3) having equipment to assist in care (66%), (4) dealing with feelings and worries (58%); and (5) having time for themselves during the daytime (58%). When asked if there was anything else not addressed in CSNAT items (an item at the end of the form labeled “other”), one caregiver mentioned support “to communicate with other family members to help them cope with husband's illness and progressive decline.” Another caregiver reported support “to communicate with wife, who lost her speech because of disease, and [caregiver] feels isolated from wife.”

Fig. 1. Percentage of caregivers expressing need for more support with each Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool domain at baseline and follow-up (N = 24).

Care advisors documented their proposed solutions/action plans on the second half of the CSNAT form. The solutions put in place by the care advisors, in discussion with the caregiver, for “knowing what to expect in the future” consisted of discussions around end-of-life issues, advance health directives, future care, and the role of palliative care. For the second priority on “knowing who to contact if concerned,” discussions centered around ambulance cover, referral to palliative care services, and a contact number at night and on weekends. For the third priority on “equipment to help care for your relative,” information was provided on the association's equipment pool and the possibility of financial aid to rent equipment if required; a bedside commode was provided to aid with deteriorating mobility; and liaison with a disability service was made available in order to provide the next level of bathroom modifications. The solutions put in place for “dealing with your feelings and worries” consisted of information on various avenues for counseling and encouragement to attend the association's carer luncheon for social support. For the fifth priority on “having time for yourself in the day,” care advisors liaised with service providers to increase the number of hours available for respite, discussed strategies for creating time for the caregiver, and encouraged caregivers to allow more people to help with relatives' care, giving caregivers more time for themselves.

Family Caregivers' Experiences of the Assessment Process

Four themes emerged from the feedback interviews with family caregivers: (1) the overwhelming caregiver journey with MND; (2) CSNAT practicality and usefulness; (3) validation of the caregiver role and empowerment; and (4) reassurance of support.

Theme 1: The Overwhelming Caregiver Journey with MND

Feedback on the assessment process triggered caregivers to describe their overwhelming journey through the course of the disease. They often related their experience of personal stress:

I do have to go to see “a shrink”— It's very stressful at times,” (FC18)

and shared how difficult they found coping with the losses brought about by MND:

They should bring in euthanasia— You wouldn't put a dog through what MND does— I find it very difficult. It really rips you apart. (FC27)

Expectations and acceptance of the personal demands of the caregiving journey were acknowledged by caregivers, as articulated by one participant:

Once you become a carer— “you have to throw part of yourself away.” I expected that. (FC14).

However, with the focus being primarily on the person with MND, the unmet needs of the caregiver were often missed:

I don't think much of me— I have … been through breast cancer myself, and don't need a lot. Yes, I did find it's all “him, him, him.” I have come across that at times. I get a bit sick of it sometimes and think, “I'm here too!” (FC11)

I lost my partner 12 months ago, and I was his carer before, and now I'm caring for my son. It's my whole life … I don't think of myself … I've got no issues really, but I mainly worry about how I'm going to cope. It's a terrible disease. (FC28)

Participants described being devastated by the hopelessness of the MND trajectory, comparing it to a cancer diagnosis, where there is often treatment and more support available and some hope of remission or recovery:

[The CSNAT] was very good. Maybe more detail about the fact that MND is terminal, unlike cancer, where some recover. (FC27)

Family caregivers commented on community's, friends', and health professionals' limited knowledge about the support available for people like them during the caregiving journey:

We're meeting people who have family and friends with MND, and they don't seem to know much about the MNDAWA. Maybe the doctors don't tell them? When we go to the GP they say, “You know more about MND than I do.” (FC11)

[I'm] looking at the support I need to give to other family members to help them cope with my husband's illness and progressive decline. (FC12)

Theme 2: The CSNAT Practicality and Usefulness

Ease of completion of the CSNAT was considered important by family caregivers of persons living with MND, as they often have myriad forms to contend with. Caregivers described using the CSNAT as “Quite a good form— one of the better ones” (FC26), with one considering it essential to complete it by themselves: “I completed it on my own. You don't want someone else to influence what you need” (FC29).

Family caregivers appreciated the opportunity to rate their needs as listed in the CSNAT: “The scale was good to rate how much you needed, then the three [priorities] more thoroughly— was good to add more detail” (FC23).

The assessment process of working together with the care advisor was valued by caregivers:

The form was really well done … It puts those little stars up there to consider. It works with the two parts—the carer's answers and the care advisor's discussion— It can only work with the two together— It's very beneficial. (FC18)

The stage of MND trajectory and how this can affect the wide range of needs of the family caregiver were considered important when implementing the CSNAT, highlighting how these needs can change rapidly. Some caregivers expressed this usefulness when their own needs changed as the disease progressed:

It was very easy. I was given the first form when it was early stages, and I didn't think I needed much. By the time of the second form, as it [MND] had progressed, my needs changed and the questions were more about what I needed then. It was helpful to talk to the care advisor about what she could do to help, going through the form together. (FC30)

As the disease progresses, you are more aware of symptoms. At first, you don't need much, and it would be “No” to nearly all [questions], but later it would be “Yes” to nearly all questions. (FC04)

The CSNAT was considered by caregivers as “a stimulus for conversation,” prompting them to “think things through, and things to be put in place” (FC09):

It covered everything. Another box to say “not needed yet” would be helpful. I've been through the emotional stage, and now I'm in the practical stage and thinking about what needs to be done. (FC30)

Theme 3: Validation of the Caregiver Role and Empowerment

It was evident that the assessment process could validate the caregiving role, as articulated by one participant:

The form made me think the role of carer was important— The fact they were being asked shows it is considered important … The form shows some evidence someone is caring to ask. (FC18)

The CSNAT process allowed caregivers to reflect on what they needed or could do themselves:

It jogged me into thinking about what I might need—equipment, financial issues. The form had things I never even dreamed about needing. It made me realize what I can do at night if I need to call someone— I have a plan now, and I know I don't have to wait until the next morning. (FC30)

It focused your mind on issues and a method to address [them]— It's not something you can sweep under the carpet— An outcome resulted from going through the form. (FC12)

The CSNAT seemed to have helped when there were conflicting needs between family caregivers and patients, such as when caregivers felt restricted in accessing support for their own needs, as articulated by this participant:

[CSNAT] helped me to have counseling, and [the service] was helpful. My husband isn't wanting to be involved much. It can be a daunting process. (FC03)

The process of completing the CSNAT provided an opportunity for carers to consider their own needs when the focus was mostly directed toward patients:

Some of the questions I hadn't thought about. Yes, I think it was beneficial for me— This time it was, “Oh, this is about me!” (FC11)

The following participant wanted to go a step further and have the focus of the needs assessment to be specifically on the caregiver, in a way reaffirming the two domains that the CSNAT covered:

The distinction between the needs of the carer and the person cared for can sometimes be blurred. You as a carer tend to focus on “How can I improve my caregiving?” rather than looking at “What do I need as an individual?” Perhaps that can be accentuated—that this is looking specifically at you and your needs as a carer—distinct from the person cared for. (FC12)

Theme 4: Reassurance of Support

A sense of relief was apparent when caregivers received the expertise and support provided by the MNDAWA:

Care advisors see these people [with MND]— They know about the disease, whereas friends don't have an understanding of MND. So even just talking with the care advisors is a help. (FC25)

I found it very helpful— Yes, [the care advisor] was able to answer some of the questions straight away and explained what to do to get different things done. (FC30)

Completing the CSNAT assessment process involved discussion with the care advisor, which often prompted awareness by the caregiver of the need for support in patient symptom management. This was improved upon by family caregivers being encouraged to attend educational sessions at the MNDAWA:

Definitely, especially from [the] MNDAWA and the course they were doing [for caregivers]. It increased my knowledge about the help available— Some things were a bit confronting, as we weren't at that stage. (FC03)

Participants were offered equipment or solutions to meet a particular need, as explained by one participant:

Yes, now I can help him out in many ways, but I can't lift, so that is the only thing I worry about. [The care advisor] is organizing a hoist for me, and that will help. (FC20)

I wasn't aware of all the equipment that was available— It's very good. I went along to a carer's lunch and was amazed at all the support available— We're so well looked after. The questions get you to think about things. You have a starting point and then can talk it through, and it gives you points you may not have considered. You have a rapport with the care advisor. (FC18)

Due to the potentially rapid deterioration associated with MND, end-of-life (EoL) issues are perhaps being considered earlier on in the disease trajectory than with other life-limiting diseases. The CSNAT can provide an opportunity to discuss this important issue where once it may have been overlooked or postponed:

One of the hardest [things] to discuss is EoL issues. [The CSNAT] focused my mind on the need to discuss this, and I ended up talking to people— I spoke to a counselor about EoL as a direct result of going through the survey. (FC12)

Care Advisors' Feedback

All care advisors found the CSNAT format simple to complete and the questions easy to understand. They reported that the CSNAT helped identify issues that “perhaps would not have come up in a normal home visit or phone call,” acknowledging that it had “been a springboard in several instances to allow a carer to explore their needs” (CA3), giving caregivers an opportunity to “verbalize their fears in a nonthreatening way” (CA2), and “It made me realize that it paid to ask the question, even though I thought I sometimes knew what the answer might be” (CA1).

The CSNAT was considered by care advisors to assist in “providing a holistic approach to carers' needs” and was seen as highlighting the support provided for caregivers: “It does open doors for that … It does let the carer be the focus of the support” (CA4). One care advisor explained, “It can uncover areas which may not have been recognized or adequately dealt with” (CA1), while another suggested that the CSNAT “acknowledges the important role carers play and the pressure put on them emotionally and physically” (CA2).

An important aspect of the CSNAT process was considered by care advisors to be “accountability and a documented record to assist the care provider” (CA3). They all advocated the CSNAT approach as an improvement over standard practice, as formalizing the process, and as providing a structured follow-up and a focus on the caregiver and family:

It is more comprehensive, provides a structured follow-up process, and there are aspects that are measurable. (CA3)

It formalizes the process and provides a means of documenting carers' needs. (CA4)

Consideration of caregiver and patient status and a sensitive approach were important when care advisors were introducing the CSNAT:

Finding the right time. There were instances when there had been an outpouring of issues. (CA1)

Sometimes when I planned to do it on a visit, it wasn't always appropriate (e.g., there were other pressing needs/issues). (CA4)

Using the CSNAT for regular reviews of caregiver needs was described by care advisors as offering “an opportunity to allow focus to be on carer rather than client— [and] allows them to have a safe place to recognize their needs, too” (CA4). An awareness of the changing and sometimes unpredictable needs of family caregivers was outlined as follows:

I think it is interesting to see how carer needs change over time and that their needs don't always follow the same trajectory as the person with MND. … Sometimes what I perceive as a very stressful time for the carer they seem to sail through, whereas something minor [for me] at another time can unleash a great emotional tide for the carer. (CA1)

Another care advisor explained that it was useful to complete the CSNAT regularly,

because even if things don't change or deteriorate, it's again acknowledging their [family carers] needs. (CA2)

However, there is a conscious struggle to keep the focus on family caregivers along with the constantly pressing needs of care recipients:

If the time is right, the discussion points can have an immediacy that works very well. At times, though, even with the best intentions from all parties, it is often the person with MND whose needs are addressed first. It's good to be constantly reminding ourselves that the bigger picture of carer and family support have an equally important role. (CA1)

DISCUSSION

Participants' involvement in this study provided them with an opportunity to share their difficult experiences, to gain increased insight into emotional concerns and enhanced awareness of supports, and to acknowledge their role as caregiver. In addition, participants described the benefits related to their increased timely access to support and better links to resources.

The CSNAT approach for identifying and addressing family caregivers' support needs was found relevant and acceptable by MND family caregivers and care advisors. For caregivers, a carer-led assessment process gave them a sense of validation, reassurance, and empowerment, as reflected in their narratives. Compared to standard practice, care advisors found the approach more comprehensive and formalized, similar to results found in previous studies using the CSNAT approach (Ewing & Grande, Reference Ewing and Grande2013; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Grande. and Howting2015b ; Reference Aoun, Deas and Toye2015a ). It provided a structured follow-up process, a means of documenting caregiver needs, and a way to acknowledge their important role. The middle stage of the disease trajectory was suggested as when the CSNAT would best be administered for regular reviews because the time of receiving the diagnosis is highly emotional and the needs are not as easily identifiable in the early stages, when symptoms are not as advanced. By contrast, more changes occur toward the middle stages, and thus more care is required. The middle stages of the MND trajectory is the period when neurological symptoms are significantly developed and the person with MND requires more assistance from a family caregiver.

By structuring and reviewing caregiver needs two months apart, evidence was obtained of a steady reduction in their perception of needs, providing good evidence for the benefit of systematically repeating this review of needs using the CSNAT approach. The single domain that revealed a rise in need over time was caregivers' beliefs and spiritual concerns, which became more important over time. This could reflect the benefit of caregiver reflection and recognition that a domain such as this can be valued.

Knowing what to expect as the illness progresses remained prominent for more than 60% at second follow-up, pointing to the continued need to educate and build the understanding that caregivers have about the future. A gradual educational process about care needs and about what to expect from the disease is clinically appropriate.

Communication issues are particularly important for people with MND and their family caregivers (Oliver & Aoun, Reference Oliver and Aoun2013; Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2014) compared to most other life-limiting diseases. This is difficult for all types of MND, as deterioration occurs, but especially when symptoms include speech impairment, which suggests that health professionals need to integrate support with respect to all facets of communication for MND caregivers into their routine practice. Strain relating to loss of intimacy can be experienced by MND caregivers (Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Atkins and Landau2006), as their partners' cognitive or physical ability to communicate diminishes, as evidenced in our and other studies (Oliver & Aoun, Reference Oliver and Aoun2013; Oyebode et al., Reference Oyebode, Smith and Morrison2013), or if behavioral changes develop (Lillo et al., Reference Lillo, Mioshi and Hodges2012). At another level, the needs of the broader family will likely depend upon the functioning of each group, their openness of communication, teamwork or cohesion, and their willingness to tolerate differences of opinion and remain mutually supportive (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, McKenzie and Bloch2006; Schuler et al., Reference Schuler, Zaider and Li2014). Communication issues were indeed raised in our study, but a larger national trial would be needed to warrant including a communication-related item to the CSNAT.

This is the first application of the CSNAT in an MND setting, a setting different from the one where it was developed in the United Kingdom (Ewing et al., Reference Ewing, Brundle and Payne2013), and different from when it was further trialed in Australia (Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Grande. and Howting2015b ) in home-based palliative care settings. In addition, the tool has been tested in our study earlier on in the caregiving journey and not just toward the end of life, a suggestion that was voiced in previous family caregiving research in the cancer field (Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Deas and Toye2015a ), and in MND (Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Chochinov and Kristjanson2014), where interventions were deemed beneficial earlier in the caregiving trajectory. Compared to caregivers who used the CSNAT in the cancer field (Aoun et al., Reference Aoun, Grande. and Howting2015b ), MND caregivers shared three of the top five priorities for support related mainly to direct carer support: “knowing what to expect in the future,” “dealing with your feelings and worries,” and “having time for yourself in the day.” However, “knowing who to contact if you are concerned” and “needing equipment to help care” were more prominent priorities for MND caregivers in our study, reflecting the earlier timing in the caregiving journey, the rapidly progressive nature of the disease, and the need to focus on practical help for patients.

LIMITATIONS

Ours was a feasibility study with a small sample size, undertaken in one geographical location. Therefore, our findings cannot be generalized. Its limitations include the profiles of people who were not included in the study during the short period of data collection. The needs of caregivers who are still working; how single, separated, or divorced caregivers fare; and what special needs arise for parents, siblings, and children of patients with MND have not been explicated in this cohort (Del Gaudio et al., Reference Del Gaudio, Zaider and Brier2012). Furthermore, care recipients were in the moderate stages of functional impairment, and there are significant challenges nearing the end of life. Such unaddressed needs specific to such circumstances could be explored in a larger national trial that would also ascertain the effectiveness of this assessment approach in improving caregivers' psychological outcomes in the MND setting.

While it may be considered a limitation in other contexts, eliciting written responses via a questionnaire from care advisors has worked well and has captured a breadth of opinion, in addition to being the care advisors' preferred form for providing feedback about their experience.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results indicate that it is feasible to deliver this supportive intervention in the MND setting, particularly using the telephone to conduct follow-up assessments. Incorporating the CSNAT into the routine practice of MND care advisors would require minimal change in the structure of normal practice and minimal cost for the organization. Travel costs and interview times would not increase, as care advisors already visit patients and their family caregivers regularly, and follow-up assessment could be done by telephone, as per usual practice. Further inquiry into implementation in MND associations nationally and internationally is considered valuable, capitalizing on the systems already in place in these associations to provide support for family caregivers.

The CSNAT has provided a formal structure to facilitate discussions with family caregivers to enable needs to be addressed. Such discussions could also inform an evidence base for the ongoing development of services, thus helping to ensure that new or improved services are designed to meet the explicit needs of family caregivers of people with motor neurone disease.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest to declare.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

SMA and KD conceived and designed the experiments. SMA and KD performed the experiments. SMA and KD analyzed the data. SMA, KD, LJK, and DWK interpreted the findings. SMA, KD, LJK, and DWK wrote the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of (1) the Motor Neurone Disease Association of Western Australia in helping to facilitate the project; (2) the care advisors in recruitment, data collection, and offering valuable advice; and (3) family caregivers in enriching the project with their feedback, given at a time of great difficulty. Many thanks are also offered to Ms. Denise Howting for assisting in the descriptive analysis.