Introduction

Currently, the scientific literature explores palliative care (PC) protocols and strategies, with established ones to be tested or validated. Structured interventions aimed at improving communication and support for end-of-life (EOL) care preferences in metastatic breast cancer patients encompass symptom management, coping strategies, and treatment decision-making. Findings demonstrate enhanced documentation of EOL care discussions in electronic health records and positive patient-reported outcomes in quality of life, anxiety, depression, and hospice utilization. Additionally, the studies offer a comprehensive review of psychological interventions for cancer patients, classifying them into cognitive-behavioral, mindfulness, and relaxation techniques (Greer et al. Reference Greer, Moy and El-Jawahri2022; Semenenko et al. Reference Semenenko, Banerjee and Olver2023).

Notably, approaching cancer patients for discussions and interventions often faces high rates of refusal, denial, fear, and sadness (Gontijo et al. Reference Gontijo Garcia, Meira and de Souza2023; Trevizan et al. Reference Trevizan, Paiva and de Almeida2023). This raises critical questions: Are cancer patients prepared for PC discussions? Do they grasp its nature? Furthermore, when is the appropriate time, and what would be their preferred mode of discussion? This brings up a broader concern about whether clinical efforts are genuinely attuned to the voices of these patients and aligned with their preferences.

PC stands as a multifaceted approach to care that transcends the mere management of symptoms associated with serious illnesses (Back Reference Back2020; Radbrunch et al. Reference Radbruch, De Lima and Knaul2020). Beyond symptom control, it encompasses discussions on quality of life, patient values, and the alleviation of physical, emotional, and spiritual distress. Importantly, these discussions extend beyond EOL scenarios, weaving through the entire trajectory of a life-threatening illness (Radbruch et al. Reference Radbruch, De Lima and Knaul2020; Strang Reference Strang2022). A delicate balance is struck in PC conversations, requiring acknowledgment of the challenging diagnosis’s reality while fostering hope through support and comfort. This dynamic process necessitates a nuanced understanding of patient needs, cultural sensitivities, and effective communication strategies (Back Reference Back2020; Kuosmanen et al. Reference Kuosmanen, Hupli and Ahtiluoto2021; Saretta et al. Reference Saretta, Doñate-Martínez and Alhambra-Borrás2022). In cancer care, early PC is pivotal, and research confirms that its initiation at diagnosis improves symptom control and enhances patient and caregiver outcomes (Gofton et al. Reference Gofton, Agar and George2022; Temel et al. Reference Temel, Petrillo and Greer2022).

Despite evident benefits, PC faces taboos and stigmas that may originate from patients, family caregivers, and/or health professional (Santos Neto et al. Reference Santos Neto, Paiva and de Lima2014). Denial and resistance to PC discussions may stem from misconceptions, equating it solely with EOL care (Saretta et al. Reference Saretta, Doñate-Martínez and Alhambra-Borrás2022). These taboos arise from a lack of knowledge about its scope, often coupled with the misconceived notion that it implies relinquishing curative treatment (Bandieri et al. Reference Bandieri, Borelli and Gilioli2023). Preserving patient autonomy and enhancing acceptance hinge on healthcare professionals’ ability to discern when and how to broach PC discussions. A fundamental aspect involves understanding the patient’s perspective and actively listening to their concerns. Dismissing misconceptions, disseminating precise information, and selecting opportune moments for dialogue play a crucial role in diminishing resistance, alleviating stigmas, and, consequently, enhancing patient acceptance of early referral to PC (Bandieri et al. Reference Bandieri, Borelli and Gilioli2023).

In this context, hearing what the patient has to say is fundamental. Giving them space to acknowledge and validate their wishes, emotions, fears, and preferences promotes trust and facilitates more meaningful conversations. This approach not only contributes to improving patient outcomes but also initiates a paradigm shift in the perception and acceptance of PC (Greer et al. Reference Greer, Moy and El-Jawahri2022). Thus, the study aimed to explore patients’ awareness levels of PC and how this awareness shapes their preferences regarding the timing and approach for discussing it.

Methods

Study design

This is a qualitative descriptive study, which constitutes the second phase of an investigation. The first phase, involving quantitative data, has already been published (Trevizan et al. Reference Trevizan, Paiva and de Almeida2023). The qualitative aspect of this study entails a content analysis based on responses to 3 guiding questions.

Participants

All patients were recruited from the Women’s Outpatient Clinic and the Chemotherapy Infusion Center of a Brazilian hospital, which stands as one of the largest cancer treatment centers in Latin America, and adhered to all predetermined eligibility criteria. The study included females diagnosed with breast cancer, aged between 18 and 75 years, who were aware of their cancer diagnosis and undergoing treatment, with an Eastern Cooperative Oncologic Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS) of ≤2. Exclusion criteria applied to individuals encountering challenges in establishing online video call connections or exhibiting significant deficits in auditory, visual, or verbal language skills. Participants were briefed on the purpose of the study and understood it. Ethical approval had been granted, and participants reviewed the study information documentation before providing their written informed consent to be involved.

Data collection and analysis

Approximately seven to 14 days before the interviews, patients received an educational leaflet developed by the researchers. The material included technical and illustrated information about PC, covering topics such as “What is PC?,” “Who is PC for?,” and “Why is PC important?.” The goal of this instructional material was to convey essential knowledge and reduce potential response bias associated with questions about “how” and “when.” Furthermore, for patients who agreed to participate, semi-structured interviews were conducted by the primary author (FBT), a male clinical psychologist, master in health psychology, with extensive experience. After completing a sociodemographic and clinical questionnaire, participants engaged in three guiding inquiries: (1) Are you familiar with the concepts of PC? What is PC all about?; (2) When do you think is the optimal timing for discussions regarding PC?; and (3) What approaches do you find most suitable for addressing PC?.

These interviews were exclusively conducted via video conferencing and carefully recorded. LFdA transcribed the interviews in full, and the transcripts were independently verified by FBT and BSRP, representing a multistep approach to ensure accuracy. FBT and LFdA independently performed a floating reading to separate the main speeches and eliminate excessive information. Following that, under the oversight of another researcher (BSRP), a peer review process was conducted until a consensus was established.

Qualitative data analysis was conducted using Bardin’s discourse analysis method, a qualitative research approach designed to systematically analyze language use in social contexts. The 3 main steps of the method included pre-analysis, where the researcher familiarized themselves with the data; analysis, involving breaking down the data into smaller units and identifying themes; and interpretation, drawing conclusions about the meaning of the data (Bardin Reference Bardin2016).

The analysis involved gathering, organizing, and preparing fully transcribed speeches to identify patterns, themes, categories, and meanings. Analysis units were selected, and a coding system was created to represent themes or concepts. Codes, concise phrases encapsulating pertinent content elements, were then grouped into clusters. An analysis of similarities and relationships among clusters followed. After the formation of clusters, the coding process began, and the complete speeches were revisited, leading to the emergence of thematic categories and subcategories. During this step, the clusters were carefully examined, and when extracts matching the categories were encountered, the respective codes were assigned. As the codes were categorized and organized into broader groups, it became possible to discern trends and patterns.

The qualitative data was analyzed using Iramuteq 0.7 software. The qualitative method followed the Consolidated Criteria for Qualitative Research Reports (Tong et al. Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007). All study processes were approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Barretos Cancer Hospital, under registration number 4.987.629.

Results

In this study, 61 patients were included. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients (N = 61)

Notes: SD: standard deviation; N: number of participants; (%): percentage; ECOG-PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status.

The interviews conducted for the study totaled a duration of 8 hours and 38 minutes, with an average duration of approximately 9 minutes per interview. Figure 1 visually presents the discourse frequency graph, illustrating the grouping and similarity of patients’ speeches. These graphs also demonstrate the clustering of patients based on similarities in their discourse.

Figure 1. Analysis of classification, occurrence and relationships of terms present in patients’ discourses and the interrelationship of terms. The proximity of lines indicates similarities, suggesting shared terms within the same speech, while greater distance signifies dispersed and isolated terms within speeches.

Figure 2 presents a network representation of term similarities. Clusters of nodes depict groups of related terms, offering insights into dominant themes and their interconnections.

Figure 2. Analysis of similarities and relationships between patients’ narrative variables. The size of nodes corresponds to term frequency, and the line thickness indicates the strength of associations.

Figure 3 provides a comprehensive overview of patients’ responses systematically categorized based on 3 key questions, resulting in the identification of 9 main categories and a total of 28 subcategories.

Figure 3. Graphic description of the questions, categories, and subcategories based on the participants’ statements.

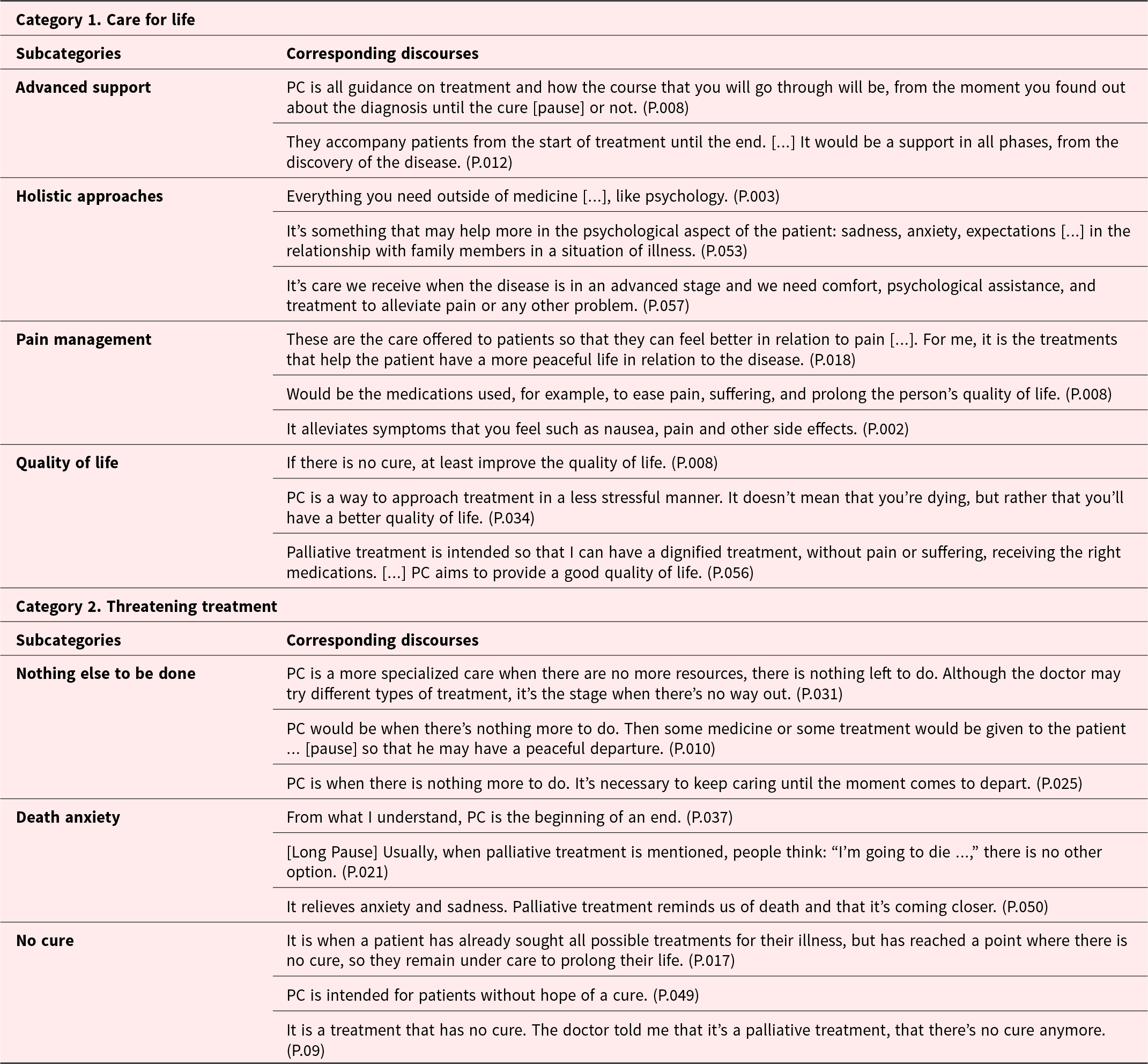

When examining patients’ perspectives on PC, the answers obtained in the first question were categorized into themes, resulting in 2 main categories and 7 subcategories, as depicted in Table 2.

Table 2. Are you familiar with the concepts of PC? What PC is all about?

Notes: P.: patient’s id; “…” indicates incomplete sentence on the part of the participant; […] indicates part of the interview omitted by the authors for conciseness.

Table 4 offers insights into patients’ preferred approaches for addressing PC. With 3 categories and 9 subcategories, these diverse perspectives underscore the need for patient-centered and adaptable approaches, considering elements such as emotional support, comfortable environments, accessibility options, clear communication, and education to enhance the PC experience.

Table 4. What approaches do you find most suitable for addressing PC?

Notes: P.: patient’s id; “…” indicates incomplete sentence on the part of the participant; […] indicates part of the interview omitted by the authors for conciseness.

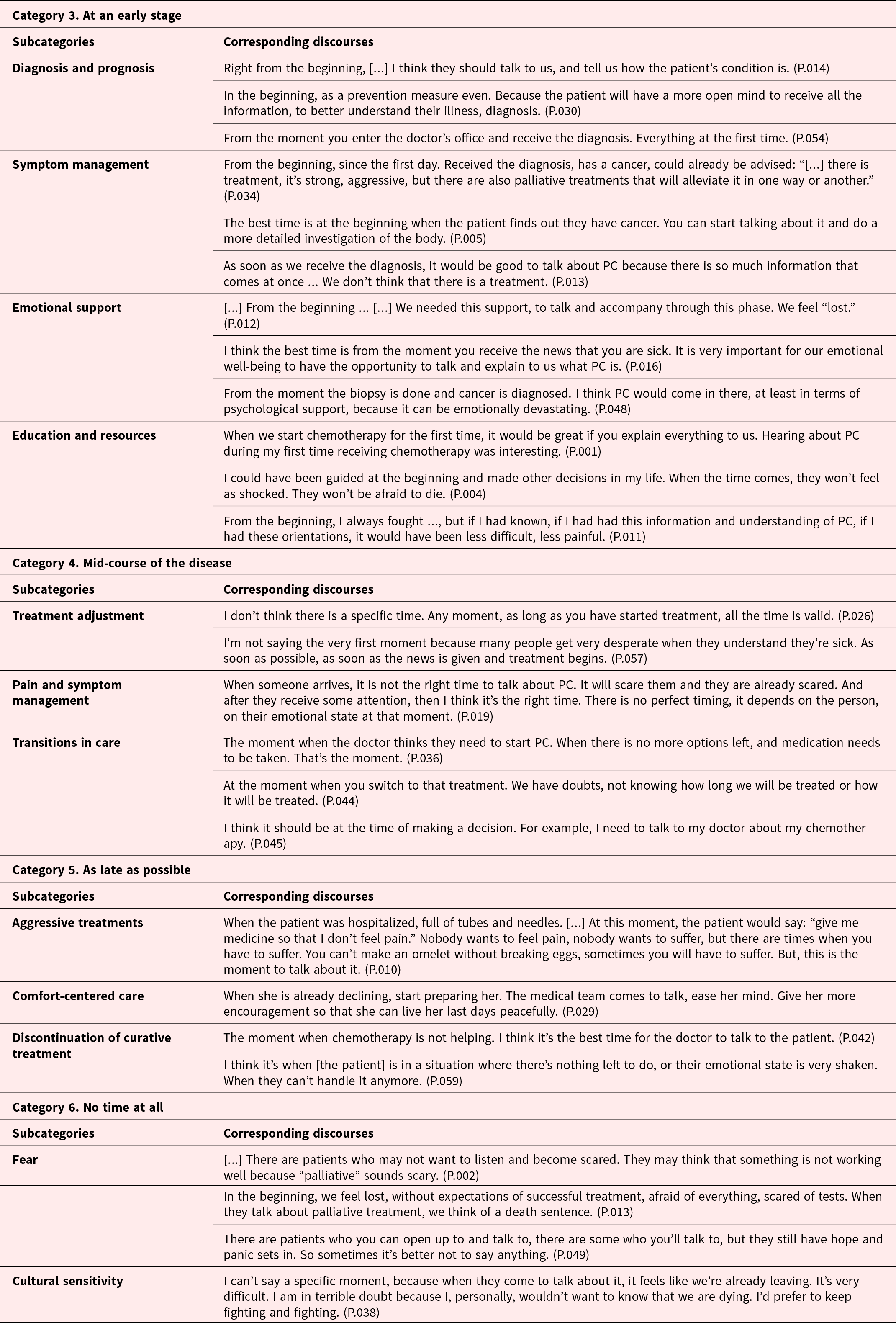

Table 3 presents patients’ views on the optimal timing for PC discussions, with responses categorized into 3 primary categories comprising 12 distinct subcategories. This elucidates the nuanced considerations surrounding when to initiate PC discussions, emphasizing the importance of individualized approaches considering emotional states, treatment progress, and cultural factors.

Table 3. When would you consider the optimal timing for discussions regarding PC?

Notes: P.: patient’s id; “…” indicates incomplete sentence on the part of the participant; […] indicates part of the interview omitted by the authors for conciseness.

Word clouds, generated from analyzed data, encapsulate patients’ insights into the definition, timing, and approach of PC (Fig. 4). Patients perceived PC as providing emotional support, pain relief, symptom management, and EOL planning, though some mistakenly believed it was only for those with no cure. Patients expressed a preference for early PC discussions, ideally at diagnosis or treatment initiation. Additionally, they emphasized the importance of clear, empathetic communication and often preferred clinic settings with prepared medical and psychological teams.

Figure 4. Representation by word cloud of the most frequent occurrences of answers to the questions.

Discussion

This study explored patients’ awareness of PC, examining optimal timing and preferred approaches. Awareness of PC influenced how and when patients found it appropriate to discuss. Patients’ perception of PC shaped their preferences in timing and approach. While associating PC with EOL may have hindered discussions, a clear awareness of PC may have stimulated earlier consideration, addressing patient goals and preferences while active participation was feasible. However, misconceptions created reluctance in some patients; nonetheless, informed individuals actively sought conversations, expressing preferences for information delivery. Shifting perception from PC as a transition from curative to supportive care fostered willingness for holistic discussions (Trevizan et al. Reference Trevizan, Paiva and de Almeida2023).

In this datas, the educational background of patients was relevant, with 47.5% having completed high school, impacting their ability to interpret and comprehend health information (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Roldan and Nichipor2022). Education shapes awareness of diagnosis and prognosis, influencing health literacy and patient engagement in PC discussions (Kuosmanen et al.Reference Kuosmanen, Hupli and Ahtiluoto2021).

When defining PC, patients viewed it as lifelong care and holistic support throughout serious illnesses (Back Reference Back2020; Wantonoro, Reference Wantonoro, Suryaningsih and Anita2022). They valued PC’s advanced support, which integrates psychological and physical aspects, reflecting holistic well-being (Rego and Nunes Reference Rego and Nunes2019). For some patients, PC was seen as beyond conventional medical approaches (Rego and Nunes Reference Rego and Nunes2019; Semenenko et al. Reference Semenenko, Banerjee and Olver2023; Wake Reference Wake2022). For patients facing incurable conditions, PC was essential for attentive monitoring and to prevent unnecessary suffering (Andriastuti et al. Reference Andriastuti, Halim and Tunjungsari2022; Chung et al. Reference Chung, Sun and Ruel2022).

Contrarily, some patients held fears and stigmas about PC (Semenenko et al. Reference Semenenko, Banerjee and Olver2023). Data revealed emotional challenges associated with limited treatment options and EOL considerations. Patients linked PC with advanced disease stages, expressing sadness and viewing it as a difficult transition (Emanuel et al. Reference Emanuel, Solomon and Chochinov2023). This balance addressed the limitations of medical interventions and existential concerns during life-threatening stages (Bennardi et al. Reference Bennardi, Diviani and Gamondi2020). Anxiety and vulnerability arose from the perception that PC was only for those actively dying (Greer et al. Reference Greer, Moy and El-Jawahri2022; Ivey and Johnston Reference Ivey and Johnston2022).

‘Nothing more to be done,” “No cure,” and “Death anxiety” were closely linked subcategories (Emanuel et al. Reference Emanuel, Solomon and Chochinov2023; Martí-García et al. Reference Martí-García, Fernández-Férez and Fernández-Sola2023; Pătru et al. Reference Pătru, Călina and Pătru2014). Patients felt sadness, viewing PC as a sign that conventional treatments were exhausted. PC was seen as daunting, marking a challenging disease transition when conventional resources were depleted (Greer et al. Reference Greer, Moy and El-Jawahri2022). Patients struggled to connect PC with alleviating death-related anxieties, intensifying anxieties due to the perceived proximity to death (Beng et al. Reference Beng, Xin and Ying2022; Emanuel et al. Reference Emanuel, Solomon and Chochinov2023).

While some patients associated PC with EOL, others emphasized early PC discussions (Gofton et al. Reference Gofton, Agar and George2022; Kuosmanen et al. Reference Kuosmanen, Hupli and Ahtiluoto2021; Temel et al. Reference Temel, Petrillo and Greer2022). Timing perspectives were influenced by emotional state and treatment progression (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Kendall and Boyd2005; Pedrini Cruz Reference Pedrini Cruz2022). Some suggested early discussions aligning with chemotherapy initiation, balancing information needs with potential distress (Gofton et al. Reference Gofton, Agar and George2022), while others found presenting this information during diagnosis disruptive (Gofton et al. Reference Gofton, Agar and George2022; Kida et al. Reference Kida, Olver and Yennu2021).

I believe that when doctors begin chemotherapy treatment, because if you receive this information earlier, when you are still in the process of exams, you become very afraid. Oncology patients often focus a lot on chemotherapy. (P.006)

Patients may delay PC discussions until the disease significantly advances, influenced by fear of death, cultural taboos, and aggressive treatments (Abel and Kellehear Reference Abel and Kellehear2022; Santos Neto et al. Reference Santos Neto, Paiva and de Lima2014). During this period, they may be more open to discussing symptom management and EOL considerations (Mathews et al. Reference Mathews, Hausner and Avery2021), but early discussions may evoke emotional implications and worries (Rhondali et al. Reference Rhondali, Burt and Wittenberg-Lyles2013).

Some patients found it challenging to identify the right time for PC discussions due to time constraints or cultural inappropriateness (Emanuel et al. Reference Emanuel, Solomon and Chochinov2023). These individuals feared such discussions because of their negative connotations related to worsening health, ineffective treatments, and impending death (Bandieri et al. Reference Bandieri, Borelli and Gilioli2023; Ivey and Johnston Reference Ivey and Johnston2022; Rhondali et al. Reference Rhondali, Burt and Wittenberg-Lyles2013; Dalal et al. Reference Dalal, Palla and Hui2011). Balancing the optimal timing for PC with patients’ preferences, cultural sensitivities, and individual readiness proved challenging.

When it comes to strategies for engaging in PC conversations, patients stressed the importance of personalized, multidisciplinary approaches, emphasizing clear, gentle, and direct communication from doctors (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Roldan and Nichipor2022; Rothschild et al. Reference Rothschild, Chaiyachati and Finck2022).

There shouldn’t be too much beating around the bush; it’s important to be straightforward, yet gentle and direct. You will find a way to ensure we don’t suffer. (P.010)

Patients favored calm settings, such as clinic rooms with psychologists, for PC discussions (Kuosmanen et al. Reference Kuosmanen, Hupli and Ahtiluoto2021). This setting was seen as conducive to addressing difficult topics (Greer et al. Reference Greer, Moy and El-Jawahri2022). Dedicated resources were crucial to simplify and facilitate PC in hospitals (Robson and Craswell Reference Robson and Craswell2022). Patients desired more interactive conversations and multidisciplinary teams for individualized care (Gofton et al. Reference Gofton, Agar and George2022; Rothschild et al. Reference Rothschild, Chaiyachati and Finck2022).

In addition, patients desired PC discussions in specialized units, staffed by PC-trained teams (Ferner et al. Reference Ferner, Nauck and Laufenberg-Feldmann2020). They believed these teams offered clearer guidance and explained unique PC aspects more effectively (Grabda and Lim Reference Grabda and Lim2021). Adapting environments to meet patients’ needs ensured a compassionate experience (Robson and Craswell Reference Robson and Craswell2022). To enhance accessibility, patients suggested more follow-ups, material distribution, and the integration of PC discussions into waiting rooms (Robson and Craswell Reference Robson and Craswell2022). Visual elements conveyed empathy and understanding, serving as educational tools (Robson and Craswell Reference Robson and Craswell2022).

Transparent communication is crucial, even in challenging situations (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Roldan and Nichipor2022). Patients advocated for post-treatment groups to share coping strategies (Bandieri et al. Reference Bandieri, Borelli and Gilioli2023; Kuosmanen et al. Reference Kuosmanen, Hupli and Ahtiluoto2021). Diverse workforces may address varied needs, but cultural sensitivity training is crucial to avoid perpetuating cultural assumptions about healthcare (Cain et al. Reference Cain, Surbone and Elk2018). Adapting PC strategies to diverse preferences and cultural contexts improves the experience (Cain et al. Reference Cain, Surbone and Elk2018). Collaboration with communities may help healthcare facilities create culturally informed approaches, harmonizing cultural perceptions with practicalities to improve the PC experience (Cain et al. Reference Cain, Surbone and Elk2018).

In conclusion, awareness is pivotal for determining the timing and nature of PC discussions, empowering patients and fostering a collaborative care approach. It is perceived holistically, offering support throughout the entire illness process. Despite some patients associating PC only with EOL care, early discussions are deemed appropriate. As treatment progresses, PC discussions alleviate the patient’s burden amid information demands at diagnosis. Serene environments, like PC clinics, are preferred, while proposed accessibility options, such as frequent follow-ups and educational materials, aim to enhance comprehension, avoid omissions, ensure clarity, and foster a support network, providing holistic health education.

This study has limitations, including the sample being limited to female breast cancer patients, potentially restricting data generalization. The study’s focus solely on female breast cancer patients is justified by the well-documented vulnerability of women to oncological diseases, especially breast cancer, and the unique psychosocial challenges they face. However, focusing on a homogeneous cohort of breast cancer patients enabled a more standardized, rigorous, and targeted analysis of the results and their implications for clinical practice. The use of video conferencing may limit the observation of body language and non-verbal cues; however, the researchers made a careful effort to assess all content, identifying changes in the tone of voice associated with emotional shifts, among other factors. Future studies should explore PC discussions in different cultural contexts and conduct longitudinal studies to assess evolving patient preferences at various disease stages.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere thanks to the Barretos Cancer Hospital, specifically the dedicated team of doctors, nurses, and nursing technicians at the Chemotherapy Infusion Center. We are also grateful to the participating patients and their family members, especially for providing them with the necessary support during the videoconferences. Lastly, we express special appreciation to the members of the GPQual for their unwavering and invaluable assistance.

Competing interests

Nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) [grant number 313601/2021-6] and São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) [grant number 2022/03842-1].