Introduction

Dignity therapy (DT) is one of the most studied brief psychotherapeutic interventions in palliative care today, designed to address the psychosocial, spiritual, and physical issues of terminally ill patients (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005; Fitchett et al., Reference Fitchett, Emanuel and Handzo2015). DT enables patients nearing death to share memories, wisdom, hopes, wishes, and dreams with those who will soon grieve their loss by preparing a legacy document. Based on the notion of legacy and generativity, DT allows patients to leave a lasting mark on the world, while also contributing to the well-being of their soon to be bereft loved ones (Chochinov, Reference Chochinov2011).

There is current evidence supporting DT's application on adults with life-threatening illnesses, largely with end-stage cancer, with significant benefits on outcomes such as dignity-related distress, meaning of life, sense of purpose, and psychosocial distress such as depression, anxiety, will to live, and desire for death (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Kristjanson and Breitbart2011; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Goddard and Opio2011; Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Östlund and Brown2012; Julião et al., Reference Julião, Barbosa and Oliveira2013, Reference Julião, Oliveira and Nunes2014, Reference Julião, Oliveira and Nunes2017). Given its ability to enhance end-of-life experience and overwhelming acceptability that is rare for any psychosocial intervention (Fitchett et al., Reference Fitchett, Emanuel and Handzo2015), research on DT's applicability on different populations has gained interest. There are now studies that have applied DT to nonterminally ill patients with chronic conditions, patients with mental disorders (Avery and Baez, Reference Avery and Baez2012; Lubarsky and Avery, Reference Lubarsky and Avery2016; Julião, Reference Julião2019), and dying children and adolescents (Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Smith and McDermid2018; Schuelke and Rubenstein, Reference Schuelke and Rubenstein2020; Julião et al., Reference Julião, Antunes and Santos2020a, Reference Julião, Santos and Albuquerque2020b; Chochinov and Julião, Reference Chochinov and Julião2021).

In the clinical and research setting, DT is performed by trained therapists that conduct face-to-face sessions with patients using a framework of questions [DT Schedule of Questions (DT-SQ)]. These questions provide a framework that is used to guide a legacy-based therapeutic intervention (Chochinov, Reference Chochinov2011).

The effect of DT on families has been very favorable, demonstrating that DT can be useful for patients, their families, and caregivers. A study conducted on bereft family members reported that DT was therapeutic, moderating their bereavement experiences (McClement et al., Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007).

A recent systematic review on the effects of DT on family members concluded that only a small body of literature examined the effects of DT on families and that future studies should be designed to investigate areas like sense of dignity and purpose, family communication, transgenerational connections, and bereavement (Scarton et al., Reference Scarton, Boyken and Lucero2018). Another systematic review to explore the outcomes of DT in palliative care patients’ family members concluded that they generally believed that DT helped them to better prepare for end of life and overcome the bereavement phase, and that the legacy document was considered a source of comfort (Grijó et al., Reference Grijó, Tojal and Rego2021). Given the salutary effects of DT on bereft family members, we wondered if there would be a benefit to having families or friends respond to a revised version of the DT-SQ following the death of their loved one, as a means of remembering them and creating a lasting legacy. The concept of legacy has been defined as “the process of leaving something behind” (Hunter, Reference Hunter2007). In a recent systematic review on the legacy perceptions and interventions for adults and children receiving palliative care, Boles and Jones (Reference Boles and Jones2021) suggest that “legacy is an enduring representation of the self — its qualities, experiences, effects, and relationships — built and bestowed across generations. Whether concrete or intangible, intentional, or serendipitous, legacies are avenues of connection, education, inspiration, or transformation.” They conclude that legacy interventions are associated with modest to significant improvements in social, emotional, and spiritual variables for patients and caregivers. The theory of continuing bonds (Klass et al., Reference Klass, Silverman and Nickman1996) highlights the ongoing nature of relationships between the bereaved and the deceased that do not end after death. There is a process of emotional construction between the bereaved and the deceased that is in a continual state of flux. Individuals establish a dynamic and ongoing inner representation of the deceased to maintain a link or some sort of relationship after the death. Unruh (Reference Unruh1983) describes the ways in which mourners preserve the identities of the deceased through the continuation of bonding activities and emotional attachments via a variety of legacies and memories, through which the deceased are remembered.

Given the results in the creation of a lasting legacy and the provision of a means of creating a continuing bond with the deceased, we explored how DT could be offered primarily as a novel bereavement intervention applied after the patient's death.

The aim of this research was to develop a framework of questions suitable for application posthumously with bereaved relatives and friends and to examine the face and content validity of the posthumous DT-SQ (p-DT-SQ) for Portuguese adults.

Methods

What triggered this research

The principal investigator (MJ), who is a palliative care physician and practices DT, was approached on two different occasions by two bereaved caregivers, asking if they could perform DT for their deceased relatives, i.e., to respond on their behalf, posthumously.

Dignity therapy and the dignity question framework for terminally ill adults

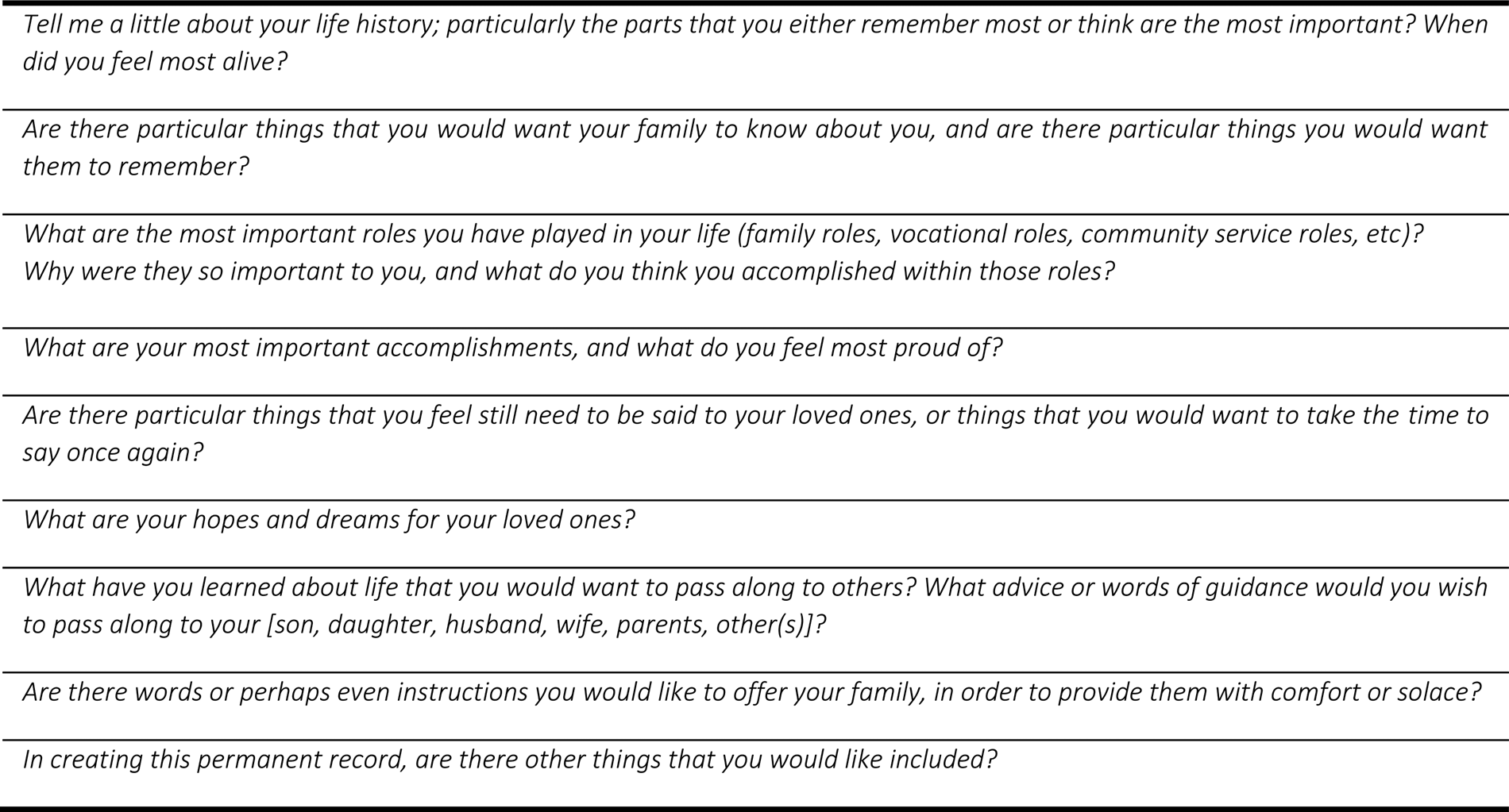

Developed by Chochinov et al. (Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005), DT is a brief psychotherapeutic intervention designed to bolster the patient's sense of meaning and purpose, reinforcing a continued sense of worth within a framework that is supportive, nurturing, and accessible for those near death. Patients enrolled in DT are guided through a conversation, in which aspects of their lives they would most want their loved ones to know about or remember are audio-recorded. DT offers patients the opportunity to talk about issues that matter most to them, to share moments that they feel are most important and meaningful, to speak about things they would like to be remembered by, or to offer advice to their family and friends. These recorded sessions provide the basis of an edited transcript or generativity document, which is returned to patients for them to share with individuals of their choosing. Therapeutic sessions are guided using a question framework (DT-SQ) comprised of questions that are based on the fundamental tenets of the Dignity Model (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and McClement2002; Figure 1). Each question is meant to elicit some aspect of personhood, provide an opportunity for affirmation, or help patients reconnect with elements of self that were, or perhaps remain, meaningful or valued. This framework provides a guide to eliciting a legacy-based therapeutic intervention.

Fig. 1. Dignity therapy question framework.

Developing the new measure: Posthumous dignity therapy schedule of questions

Research phases

The development of our study consisted of six stages, based on guidelines by Beaton and colleagues (Reference Beaton, Bombardier and Guillemin2000) although some minor protocol deviations were taken due to logistical challenges, including the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 2). This work all took place between February and April 2021. This study received ethical approval from the Inválidos do Comércio IPSS Internal Advisory Board (of.17, 2021.03.04).

Fig. 2. Flowchart of the study.

Phase 1: Creation of the p-DT-SQ for adults and translation to European Portuguese

Following two bereaved relative's requests to engage in DT posthumously as proxies for their deceased loved ones, we undertook adapting DT-SQ for this purpose. Besides Dignity Therapy, Dr. Chochinov has developed other personhood eliciting question frameworks, designed for application within palliative care (Pan et al., Reference Pan, Chochinov and Thompson2016; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Chochinov and McClement2018). The prototype posthumous Dignity Therapy Question Framework was created by rewording the entire DT question framework, targeting each question toward the bereaved family member, and framing the question in terms of their deceased loved one. This resulted in questions suitable for bereaved family members or friends based on the fundamental elements of the Dignity Model and DT itself.

This initial adapted framework of questions (p-DT-SQ) was independently translated to European Portuguese by a bilingual native Portuguese researcher who was unaware of the original DT-SQ and did not have knowledge or training in DT-related themes.

Phase 2: Expert committee adaptations

This two-round phase consisted of an expert committee analysis of the initial European Portuguese version of the p-DT-SQ. The committee was comprised of 12 members, four of whom were familiar with the Dignity Model and formally trained in DT. Committee membership included adult palliative care physicians, family physicians, adult psychologists, palliative care nurses, and palliative care researchers and academics. Committee members were asked to provide and send their feedback questionnaires on the European Portuguese p-DT-SQ initial version regarding: (1) belief that the newly created questions framework captured the fundamental dimensions of the Dignity Model and DT evaluated by a “yes/no” question; (2) belief that the p-DT-SQ could be answered by bereaved relatives or friends, serving as a useful clinical tool and bereavement intervention evaluated by a “yes/no” question; (3) overall comprehensibility of each item, including linguistic relevance (Mokkink et al., Reference Mokkink, Terwee and Patrick2010), was evaluated using free responses at the end of the survey and not for each particular item; (4) general comments, revisions, and possible inclusion of other relevant questions or ideas. Each panel member was then asked if they agreed to provide overall approval of the adapted version during a final individual meeting with the principal investigators to discuss any conflicting items. Due to COVID restrictions, all communications were made by email and telephone.

Phase 3: Creation of a consensus European Portuguese p-DT-SQ version

After receiving all the experts’ inputs and versions in the second round, MJ and BA developed a single consensus version of the p-DT-SQ. To further strengthen this phase, a linguistic expert was consulted to revise the finalized consensus version and no changes were deemed necessary.

Phase 4: Back-translation and DT's original author agreement

The European Portuguese p-DT-SQ consensus version was back-translated to English and sent to Dr. Chochinov for approval.

Phase 5: Face validity

The p-DT-SQ consensus version was used to conduct face validation. Potential eligible people comprised of elderly residents and their healthcare providers from a large Senior Residence in Lisbon were approached between March and April 2021. We used convenience sampling. The following inclusion criteria had to be met: (1) aged 18 or older; (2) absence of a major depressive disorder assessed using the DSM-V criteria; (3) mini-mental state examination ≥20; (4) ability to provide written informed consent; and (5) ability to read, speak, and understand Portuguese. Subsequently, the research assistant verified eligibility, obtained the informed consent and socio-demographic data, along with the Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG; Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Maciejewski and Reynolds1995; Frade et al., Reference Frade, Sousa and Pacheco2010). This scale measures maladaptive symptoms of loss and ICG scores >25 indicate maladaptive symptoms of loss. The ICG was used to gauge the extent and intensity of any underlying grieving process. This is important given that the p-DT-SQ is being developed to be used as a potential intervention for people who are bereft. We did not exclude participants based on ICG scores, given we wanted input from participants with varying degrees of grief, including those who were or were not actively grieving.

Next, each eligible person was introduced to the study protocol and the p-DT-SQ, allowing the necessary time to read it and to clarify any emerging questions. Each participant was reassured that emotional support would always be available during the interview or afterwards if needed. After agreeing to participate and completing the initial part of the protocol, participants were asked to complete a feedback questionnaire on their appreciation, perceptions, and possible effectiveness of p-DT-SQ (rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 [strongly disagree] to 7 [strongly agree]). They were also invited to write any additional comments at the end of the questionnaire.

Phase 6: Content validity

Further content validity was undertaken by three independent experts, consisting of two palliative care physicians and one nurse, all active clinicians with advanced palliative care training and acquainted with DT. The Content Validity Coefficient (CVC) was calculated based on the common formula to evaluate language clarity, practical relevance, and theoretical relevance (each rated on a 5-point rating scale ranging from 1 [not clear/pertinent] to 5 [very clear/pertinent]) (Hernández-Nieto, Reference Hernández-Nieto2002). A CVC > 0.8 was considered acceptable (Hernández-Nieto, Reference Hernández-Nieto2002).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS®) software 27.0 for Windows®. Descriptive statistics was used to describe the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants and responses to the feedback questionnaire.

Results

The European Portuguese version of the p-DT-SQ was coined Protocolo de Perguntas da Terapia da Dignidade Póstuma (Posthumous Dignity Therapy Schedule of Questions).

The full European Portuguese and English questionnaires are presented in Figure 3.

Fig. 3. The European Portuguese Posthumous Dignity Therapy Schedule of Questions.

Data collection

Participants

Our study was conducted in a large Senior Residence in Lisbon. From the 63 eligible participants, 50 agreed to take part in the study (elderly people = 10; healthcare professionals = 40). Eight participants declined participation (n = 2, no reason given; n = 6, feared that their participation in the study could affect their psychological wellbeing and bereavement process) and five did not meet inclusion criteria (n = 3, major depressive disorder; n = 2, mini-mental state < 20) (response rate = 79%). Seventy-eight percent of participants were female (n = 39). Participants’ overall characteristics are outlined in Table 1. Among the healthcare professionals, most were female (83%), had a mean age of 39 (SD = 11.2). Elderly people were also mostly female (60%) and had a mean age of 82 (SD = 9.2).

Table 1. Summary characteristics of the participants

SD, Standard Deviation; some categories do not add up to 40 (healthcare professionals) or to 10 (elderly) due to missing data.

a Participants could report more than one medical condition.

Phase 2: Expert committee adaptations

All panelists considered the newly created questions framework captured the fundamental dimensions of the Dignity Model and DT and that the p-DT-SQ could be answered by bereaved relatives or friends, serving as a useful clinical tool and bereavement intervention; five panelists had no changes to suggest on any item, the remaining offered minimal suggestions regarding the use of synonyms and the use of plural and/or singular use verb forms in two items. Four panelists suggested adding one item in relation to fulfillment or unfulfillment of wishes of the deceased patient. One panelist suggested replacing “loved one” with a blank space for their name.

Phase 3: Creation of a consensus European Portuguese p-DT-SQ version

MJ and BA developed a single consensus version of the p-DT-SQ reaching 98% agreement. In the process of creating the consensus version of the p-DT-SQ, the new item was added related to the “fulfillment of unfulfilled wishes” of the deceased (Question #11). The Portuguese expression “ente querido” (loved one) was replaced with a blank space for the participant to fill in the person's name, making the question framework more personalized.

Phase 4: Back-translation and DT's original author agreement

Dr. Chochinov approved the consensus version created for posthumous use, meriting further testing and consideration as a novel bereavement intervention based on the elements of the Dignity Model and DT itself.

Phase 5: Face validity

As reported in Table 2, participants considered that the p-DT-SQ was clear (M = 6.48, SD = 0.81), easy to understand (M = 1.38, SD = 0.88) and that questions were not difficult to answer (M = 1.78; SD = 1.33). Participants perceived that the instrument was not lengthy (M = 1.88, SD = 1.52) and the questions did not make them feel uncomfortable (M = 1.54, SD = 1.42). They also indicated that answering the p-DT-SQ could positively affect the way themselves (M = 5.69, SD = 1.90) or others (M = 5.66, SD = 1.87) would remember their loved ones, allowing them to understand the deceased's concerns (M = 5.48, SD = 1.49), interests (M = 5.62, SD = 1.46), and values (M = 5.80, SD = 1.36). Participants felt that answering the protocol posthumously could be a good starting point for a conversation about the deceased with people who were important in their loved one's life (M = 6.04, SD = 1.53) and would recommend it to others who have also lost someone they love (M = 6.30, SD = 1.11). When asked about the preferred format for their responses, 80.0% preferred written text, followed by video and audio recording (14% and 12%, respectively). Eighty-one percent of participants mentioned they would prefer to answer the p-DT-SQ alone and 19.1% would like to be accompanied by someone from their family, a friend, or a therapist. No participant reported a need for emotional support during or after completing the study protocol. Only 12 participants added brief comments in the open question of the feedback questionnaire, hence, no qualitative analysis was performed (see Figure 4). After the analysis of all participants’ answers, no changes were deemed necessary on the p-DT-SQ final consensus version created after phases 2 and 3.

Fig. 4. Written comments by the participants in the feedback questionnaire.

Table 2. Participants’ appreciations on the posthumous dignity therapy schedule of questions (N = 50)

p-DT-SQ, Posthumous Dignity Therapy Schedule of Questions; SD, Standard Deviation.

a Responses rated on a Likert scale: 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree”.

Phase 6: Content validity

Table 3 shows the CVC regarding language clarity, practical, and theoretical relevance of the p-DT-SQ. All items presented CVC values above the acceptable recommended level (>0.80). The CVCs of the scale, by rater, were high: 0.99 for rater 1, 0.98 for rater 2, and 0.95 for rater 3. The CVC for the total scale was 0.94.

Table 3. The content validity coefficient per item of the p-DT-SQ

CVC, Content Validity Coefficient; p-DT-SQ, Posthumous Dignity Therapy Schedule of Questions.

Discussion

Since its development, DT has shown beneficial effects on several dimensions of end-of-life experience, for both patients and their caregivers. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to create and validate an adapted version of the DT-SQ to be used posthumously by bereaved family and friends. Both elderly participants and healthcare providers reported overwhelming support for the proposed application of DT as a posthumous bereavement intervention.

The creation of the p-DT-SQ was the result of a rigorous process, which included input from both seniors and healthcare professional participants. The evidence from participants and our expert panel indicated high content validity, indicating that all items were deemed appropriate, clear, and easy to answer; and the questionnaire reasonable in length. The broad age range in our sample ensured that the assessment of this instrument was made by people with different life experiences and at different stages in their life cycle. Although we asked participants to think about their responses to questions in reference to deceased loved ones, this did not seem to cause distress, which is consistent with the ICG mean scores below 25, indicating low degrees of grief-related distress.

No questions were considered uncomfortable and no participant asked for psychological support during or after the study closed. It is possible that participants who accepted our invitation were more comfortable with these issues, given that six eligible participants declined participation fearing it could affect their psychological wellbeing and possibly bereavement process. We did not exclude participants with higher ICG scores, given the possibility that this new application of DT might have clinical utility in those specific individuals. Interestingly, some comments in the open questions section seem to indicate that during the present study some participants recalled their deceased loved ones in a very vivid, intense way and almost seemed to be at peace or had resolved their grief. This should be explored in future research applying posthumous DT in bereaved people.

Most participants indicated that they were happy to answer the p-DT-SQ alone, without the presence of a therapist, friend, or family member, reporting that they would feel confident to answer, write, and record their responses on their own, perhaps reflecting comfort regarding the nature of the items. We cautiously interpret this as a sign of clinical applicability and safety; again, this would have to be explored and tested in the future studies.

As with many other DT-related instruments, such as the Patient Dignity Questionnaire, and the This Is ME Questionnaire (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, McClement and Hack2015; Pan et al., Reference Pan, Chochinov and Thompson2016; Julião et al., Reference Julião, Courelas and Costa2018; Lemos Caldas and Julião, Reference Lemos Caldas and Julião2018; Lemos Caldas et al., Reference Lemos Caldas, Julião and Santos2020), the p-DT-SQ seems to have the capacity to serve as a starting point for conversations among those who have lost their loved ones, unlocking memories regarding the decease's interests, concerns, and values.

This study has limitations, namely being conducted in a single center and during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have caused some eligible participants to decline participation, given the strenuous emotional circumstances. It is also the case that we used a questionnaire that elicited binary “yes/no” feedback from the expert committee; using a numerical scoring system might have added further robustness to our findings.

Future interviews with bereaved family members may also provide more information about their comprehension of the p-DT-SQ, thus refining this clinical tool before introducing it into future trials. Most notably, while we developed a framework of questions to enable a posthumous application of DT for those who are bereft, the validation study we conducted took place among elderly residents and healthcare professionals. Clearly future studies to test this novel intervention in those who are actually grieving are now warranted.

Conclusion

The European Portuguese p-DT-SQ is clear, comprehensible, acceptable, and well aligned with the fundamentals of DT. Our data suggest that it may be beneficial for those who are grieving. Future research is warranted on the impact of p-DT-SQ as an intervention for those trying to cope with the death of loved ones. Implementing the p-DT-SQ could offer a unique and pragmatic alternative for people navigating their way through bereavement. This posthumous form of Dignity Therapy provides an outlet that honours the deceased, while also providing a means for the bereft to assuage their own grief.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the elderly residents and professionals of Inválidos do Comércio, IPSS for participating so enthusiastically in our study. A word of gratitude to L. and J. for triggering this important research.

Author contributions

MJ, HMC, BA, CS, and CF were responsible for the conception, design, and writing the initial draft. MJ, HMC, BA, and CS were responsible for the database managing and initial data analysis. CS was responsible for the statistical analysis. All co-authors made the revision of the final report and had full access to all the data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.