Introduction

The intensive care unit (ICU) serves as a lifeline for acutely ill patients, providing comprehensive care and monitoring in a highly specialized environment. Critically ill patients often encounter a complex amalgamation of medical interventions, clinical uncertainty, and physical and emotional distress, the combination of which has been associated with numerous physical, psychological, and cognitive sequelae (Rawal et al. Reference Rawal, Yadav and Kumar2017). Survivors of critical illness frequently struggle to remember their experiences during their stay in the ICU and to differentiate concrete remembered experiences from concurrent hallucinations and delusions (Maartmann‐Moe et al. Reference Maartmann‐Moe, Solberg and Larsen2021).

Recall of critical illness has implications for patient experience, psychological outcomes, and long-term quality of life. Patients who have experienced intubation and sedation in an ICU setting demonstrate significantly reduced recall when compared to controls (Chenaud et al. Reference Chenaud, Merlani and Luyasu2006). Recollections may be of factual care experiences, noise, or dreams/delusions, but are frequently associated with discomfort/uncomfortable events and experiences (Chenaud et al. Reference Chenaud, Merlani and Luyasu2006; Maartmann‐Moe et al. Reference Maartmann‐Moe, Solberg and Larsen2021; Marra et al. Reference Marra, Pandharipande and Patel2017). Adverse and delusional memories of critical illness have been associated with the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (Bashar et al. Reference Bashar, Vahedian-Azimi and Hajiesmaeili2018; Myhren et al. Reference Myhren, Ekeberg and Tøien2010) and similar symptoms after discharge. Studies of recall in other populations, such as patients receiving anesthesia, demonstrate that recall is poor even in awake and responsive patients receiving acute care procedures and accompanying medications (Chadha et al. Reference Chadha, Dexter and Brull2020). These studies suggest that patient-reported outcomes and measured satisfaction may not reliably reflect true recall of the perioperative experience (Chadha et al. Reference Chadha, Dexter and Brull2020; van de Leur et al. Reference van de Leur, van der Schans and Loef2004). Studies exploring informed consent in critical illness have yielded similar findings (Schelling Reference Schelling2007), suggesting that even those critically ill patients who appear awake, alert, and able to participate in a complex consent process may not remember their care experience reliably.

While recall may be unreliable in critical illness, critically ill patients commonly report psychological and existential distress. Distress has been demonstrated to be high even in the approximately 1 in 5 critically ill patients who are awake, alert, and comparatively stable (Hadler and Dexter Reference Hadler and Dexter2023; Mergler et al. Reference Mergler, Goldshore and Shea2022; Reference Zhuang, Dexter and HadlerZhuang et al. in press). Treatment of distress in this population is complicated by fluctuating medical states, numerous transitions in care, and challenges in identifying high-risk patients (Hadler and Dexter Reference Hadler and Dexter2023; Hadler et al. Reference Hadler, Dexter and Epstein2023a). Limited recall of critical illness experiences further complicates intervention design and evaluation in distress related to critical illness (Hadler and Dexter Reference Hadler and Dexter2023; Hadler et al. Reference Hadler, Dexter and Epstein2023a). In this prospective cohort study, we sought to compare recall and distress in critically ill patients with patients experiencing chronic illness (end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis).

Methods

This study was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board (IRB).

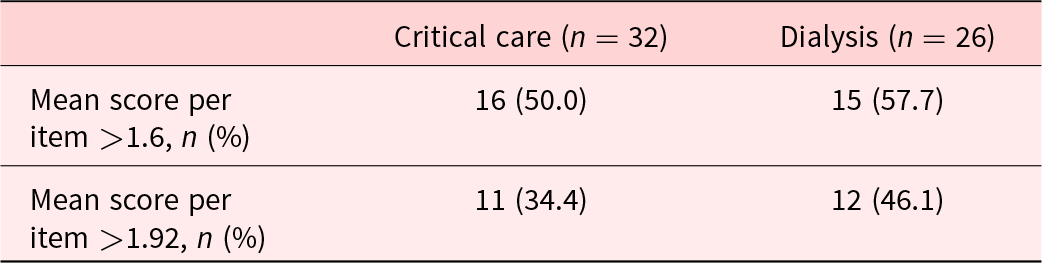

Recruitment: Critically ill participants were recruited from any of 3 ICUs across a major academic hospital. Patients were eligible for recruitment if they had been admitted to the ICU for greater than 48 hours and, based upon chart review, were unlikely to be sedated or delirious at the time of assessment (Mergler et al. Reference Mergler, Goldshore and Shea2022; Zhuang et al. Reference Zhuang, Dexter and Hadlerin press). Dialysis patients were recruited from 2 outpatient dialysis facilities in the same city and associated with the same health system. The patients were approached during a dialysis session. After a potential participant had consented to the study, a research assistant (SW or YH) would write the participant’s name on a name badge that they would affix to their own (the interviewer’s) chest. They would then review the Patient Dignity Inventory (PDI) (Chochinov et al. Reference Chochinov, Hassard and McClement2008) with the participant, manually documenting their responses. We characterized a mean per-item score of ≥1.6 as “above average distress” based on this being the median response (78/155) in an earlier cohort study of ICU patients at a different hospital (Hadler et al. Reference Hadler, Dexter and Mergler2023b). Severe distress was characterized based upon work by Crespo et al. (Reference Crespo, Rodríguez-Prat and Monforte-Royo2020) in their studies of dignity and desire for death. From their Table 3, a mean per-item score of ≥1.92 was associated with finding death preferable to the participant’s current condition (Crespo et al. Reference Crespo, Rodríguez-Prat and Monforte-Royo2020; Hadler et al. Reference Hadler, Dexter and Mergler2023b; Zhuang et al. Reference Zhuang, Dexter and Hadlerin press). Demographic and medical data were subsequently collected from the electronic medical record.

Participants received follow-up either in-person or telephonically within 7–10 days of their initial interview, with subsequent plans to reassess in following weeks if recall was substantial. Patients who received telephonic follow-up had either been discharged from the hospital or were unavailable during a subsequent dialysis session. Follow-up interviews were scripted and were conducted by the same research assistant who had previously interacted with the participant. Specifically, the interviewer asked participants what they recalled from the previous week’s interactions. Prompts were provided when respondents did not provide additional information. Respondents were first asked if they remembered the interviewer, second the name badge (with the participant’s name), and third, whether they remembered having participated in a survey and, if so, its content. Survey content was grouped into the 4 themes identified in Mergler’s factor analysis of the PDI among critically ill patients (Mergler et al. Reference Mergler, Goldshore and Shea2022).

The scoring rubric was designed before study initiation based on previous recall studies in patients undergoing ambulatory surgery (Chadha et al. Reference Chadha, Dexter and Brull2020). Recall of an item without a prompt (e.g., the respondent recalled their name on the interviewer’s name badge independently) received 1 point; recall after prompting was assigned half a point. A respondent who recalled the survey, the name badge, and all 4 themes would receive a maximum of 6 points (see Appendix). If a respondent had only 2 points, the implication would be recall would be limited to recognition of the practitioner as being part of the patient care team, asking questions but without context.

To quantify recall, we transcribed the recorded follow-up interactions and graded them against the rubric. Median responses were then described by making comparison to the rubric. Our primary interest was the median recall score for the ICU patients and the 95% 2-sided Clopper–Pearson exact confidence interval for that score. Groups were compared using the exact Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test, with Student’s t-test with unequal variances as sensitivity analysis (Stata v18.0, StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Our initial sample size selection was based on a paired analysis of 30 patients in each group. However, the race of the patients differed between groups and there were far more ICU than dialysis patients available to enroll at the health system. Therefore, we made no consideration to pairing patients.

Results

Between July and September 2022, 137 critically ill and 39 dialysis patients met the initial screening criteria. There were 42 (30.6%) critically ill patients who initially participated in PDI completion; 74 (54.0%) of the individuals screened were either asleep or receiving care at the time of initial in-person screening and were not approached for consent; and 21 (15.3%) patients declined to participate. Among the 42 patients, 32 (76.2%) participated in the final analysis, with the remaining 10 (23.8%) lost to follow-up or declining to participate in the follow-up interview. Among the 39 dialysis patients screened, 26 (66.7%) were included in the final analysis, 12 (30.8%) declined to participate, and 1 died before follow-up could occur. The number of patients receiving routine outpatient treatment at dialysis centers affiliated with our hospital system limited the availability of dialysis patients. The critical care and dialysis groups differed in key features, including age and race (Table 1).

Table 1. Study population

Participants in each group appeared to experience distress aligning with different themes identified in previous work (Hadler et al. Reference Hadler, Dexter and Mergler2023b; Mergler et al. Reference Mergler, Goldshore and Shea2022). When we examined the mean scores by theme between groups, ICU patients reported more distress related to dependency, and dialysis patients reported more distress related to interactions with others and peace of mind. Mean scores for illness-related scores were comparable, although it must be noted that these themes are not distinct dimensions (Mergler et al. Reference Mergler, Goldshore and Shea2022) and were identified using factor analysis from ICU patients, not dialysis patients (Supplemental table). In keeping with previous studies assessing dignity in critical illness using the PDI (Crespo et al. Reference Crespo, Rodríguez-Prat and Monforte-Royo2020; Mergler et al. Reference Mergler, Goldshore and Shea2022; Zhuang et al. Reference Zhuang, Dexter and Hadlerin press), we calculated overall mean scores per item in respondents. The means (standard deviations) were 1.85 (0.78) among ICU patients and 1.92 (0.82), respectively, among dialysis patients. There were 50.0% (n = 16) of critically ill patients and 57.6% (n = 15) of dialysis patients who had a mean score per item of >1.6 (i.e., reported severe distress). And 34.4% (n = 11) of critically ill patients and nearly half of dialysis patients (46.1%, n = 12) had a per-item score >1.92, associated with preferring death over their current state (Crespo et al. Reference Crespo, Rodríguez-Prat and Monforte-Royo2020) (Table 2).

Table 2. Dignity-related distress

Recall scores in both groups were low. Among ICU patients, the 95% upper 2-sided confidence interval for the median level of recall was a score of 1.5, suggesting that the participant had no recall of the event beyond remembering that they had interacted with the interviewer. The observed median was 1.25. No significant differences were observed between groups by multiple analysis methods (Table 3).

Table 3. Recall scores

Discussion

Retrospective studies of recall in critically ill patients have demonstrated that many critically ill patients may have some component of ICU recall; however, these reported memories are highly subjective (e.g., memories of dreams) (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Rickard and Rajbhandari2006, Reference Roberts, Rickard and Rajbhandari2007; Rundshagen et al. Reference Rundshagen, Schnabel and Wegner2002). Patients who experience recall of concrete events largely remember unpleasant stimuli such as endotracheal intubation (Rotondi et al. Reference Rotondi, Chelluri and Sirio2002; Rundshagen et al. Reference Rundshagen, Schnabel and Wegner2002). The single prospective study of recall in critically ill patients centers upon the experiences of early mobilization protocols in cancer patients mechanically ventilated in the setting of acute respiratory failure (Hsu et al. Reference Hsu, Campbell and Weeks2020). In our study, we sought to understand short-term recollections in a group of critically ill patients for whom we expected to have a higher probability of recall – patients who required ICU admission for at least 2 days but whose disease states and care needs were such that they were without delirium, and alert when awake. These patients represent approximately one-fifth of all critically ill adult patients at tertiary care facilities (i.e., even at hospitals taking care of the sickest of patients) (Hadler and Dexter Reference Hadler and Dexter2023). Our current findings suggest that, even though this cohort of patients objectively appears more likely to recall discrete events from their ICU stay, they are unlikely to recall significant components of a survey assessing their distress during ICU admission. Even having completed the survey was the practical limit of reliable recall.

While recall was poor, dignity-related distress was notably high in both groups: nearly half of critically ill patients and almost two-thirds of dialysis patients reported severe dignity-related distress, in many cases sufficiently severe that death would be preferable to their current state (Crespo et al. Reference Crespo, Rodríguez-Prat and Monforte-Royo2020). These findings align with other studies of dignity-related distress in critical illness (Mergler et al. Reference Mergler, Goldshore and Shea2022; Zhuang et al. Reference Zhuang, Dexter and Hadlerin press) and suggest that dignity-related distress is common among critically ill patients. Developing an intervention to address dignity-related distress in critical illness is essential. We previously showed that the family lacks significant insight into the distress, so these assessments should not wait for family availability (Zhuang et al. Reference Zhuang, Dexter and Hadlerin press). Our current study’s findings suggest that any intervention designed to target distress in critical illness would need to be (1) promptly deployable and (2) independent of recollection of the intervention to be impactful or to assess impact.

Recall was also poor in dialysis patients. Dialysis patients also reported more severe distress. While the PDI itself has not been validated in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis, approximately 25% of patients with end-stage renal disease report symptoms of depression. Other forms of distress are also common (Goh and Griva Reference Goh and Griva2018; Palmer et al. Reference Palmer, Vecchio and Craig2013; Zalai et al. Reference Zalai, Szeifert and Novak2012). A series of cognitive behavioral therapy-based interventions have been trialed or are being tested in dialysis patients, some with at least a short-term impact upon distress in these patients (Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Moss-Morris and Game2016; Rodrigue et al. Reference Rodrigue, Mandelbrot and Pavlakis2011), and may offer a path forward toward treating distress in both groups.

Our study has several notable limitations. Participants received treatment through a single medical center, representing local demographics and care characteristics (e.g., among the ICU patients, 97% were white). Critically ill respondents frequently conflated survey participation with discharge planning interactions, suggesting that the high frequency of visitors discussing, in some cases, overlapping topics may dilute the impact/ memorability of any 1 encounter. The critically ill patients at the study hospital largely demonstrate mild severity of illness as evidenced by limited utilization of life support (Hadler et al. Reference Hadler, Dexter and Epstein2023a; Table 1). Our earlier retrospective cohort study characterized >10,000 of these patients over 10 years (Hadler et al. Reference Hadler, Dexter and Epstein2023a). Most patients alert and without delirium in the ICU for 2 days remained so for at least 4 days, principally because of recovery and ICU discharge (Hadler et al. Reference Hadler, Dexter and Epstein2023a). Given evidence suggesting that poor recall and lack of memory in critical illness is associated with severity of illness (Ringdal et al. Reference Ringdal, Plos and Lundberg2009), the comparative health of our study population reinforces our findings because even those patients had little recall. Finally, in electing to compare recall and distress in critically and chronically ill patients, we did not necessarily capture distinctions between distress/recall in patients with chronic or critical illness and a population without serious illness. However, our findings suggest that dignity-related distress is high in patients with both chronic and critical illness, findings corroborated by other work (Chochinov et al. Reference Chochinov, Johnston and McClement2016). Further work is needed for treatment options for dignity-related distress within the constraints identified in the current and earlier studies.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951524000725.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare none.

Appendix

Patient Dignity and Recall Follow-up Script

Research team member: Good morning/afternoon, I am here to follow up with you about a study you participated in about 1 week ago. Do you mind sharing with me anything you remember from that visit?

1. Do you remember what I asked you to do?

2. Do you remember anything specific about what I was wearing?

a. Prompt: like a name tag?

If answer to [1] is “No”, data collection stops here. If answer to [1] is “yes”, proceed with the following questions:

I’d like you to think for 2 minutes about what you remember. If you’d like, you can use this pencil and paper (provided by the study team) to make notes. Wait 2 minutes; provide pencil/paper.

3. Do you remember anything about what was on the survey?

If no, proceed to prompts. If yes, elicit further information, then can proceed to prompts if gaps:

a. Prompt 1: Do you remember any questions about symptoms or how you feel and think about your illness? (Illness-related concerns) If yes, ask for specific information about which questions remembered; if no, proceed to next prompt.

b. Prompt 2: Do you remember any questions about your relationships with other people? (Interactions with others) If yes, ask for specific information about which questions remembered; if no, proceed to next prompt.

c. Prompt 3: Do you remember any questions about your state of mind or being at peace? (Peace of mind) If yes, ask for specific information about which questions remembered; if no, proceed to next prompt.

d. Prompt 4: Do you remember any questions about needing help or your level of independence? (Dependency) If yes, ask for specific information about which questions remembered; if no, proceed to next prompt.

Following completion of questions: Thank you for your time and participation.

Scoring:

1. 1 point for recall that participated in survey

2. 1 point for recall of name tag, 0.5 point with prompt

3. 1 point per theme remembered independently, 0.5 point per theme remembered with prompt.

Maximum number of points achievable: 6 (full recall of interaction and all 4 themes without prompts).