Despite Angola's high biodiversity, the political unrest during 1975–2002 took a heavy toll on its wildlife, which suffered from widespread poaching and bushmeat hunting (Huntley, Reference Huntley2017). Although little is currently known about the status and trend of most Angolan wildlife populations, iconic and threatened species such as the cheetah Acinonyx jubatus and African wild dog Lycaon pictus are presumed to have suffered drastic declines and range contractions (Woodroffe & Sillero-Zubiri, Reference Woodroffe and Sillero-Zubiri2012; Durant et al., Reference Durant, Mitchell, Ipavec and Groom2015). However, the Angolan government has recently shown signs of political will to improve knowledge of the country's biodiversity, including for the large carnivore species.

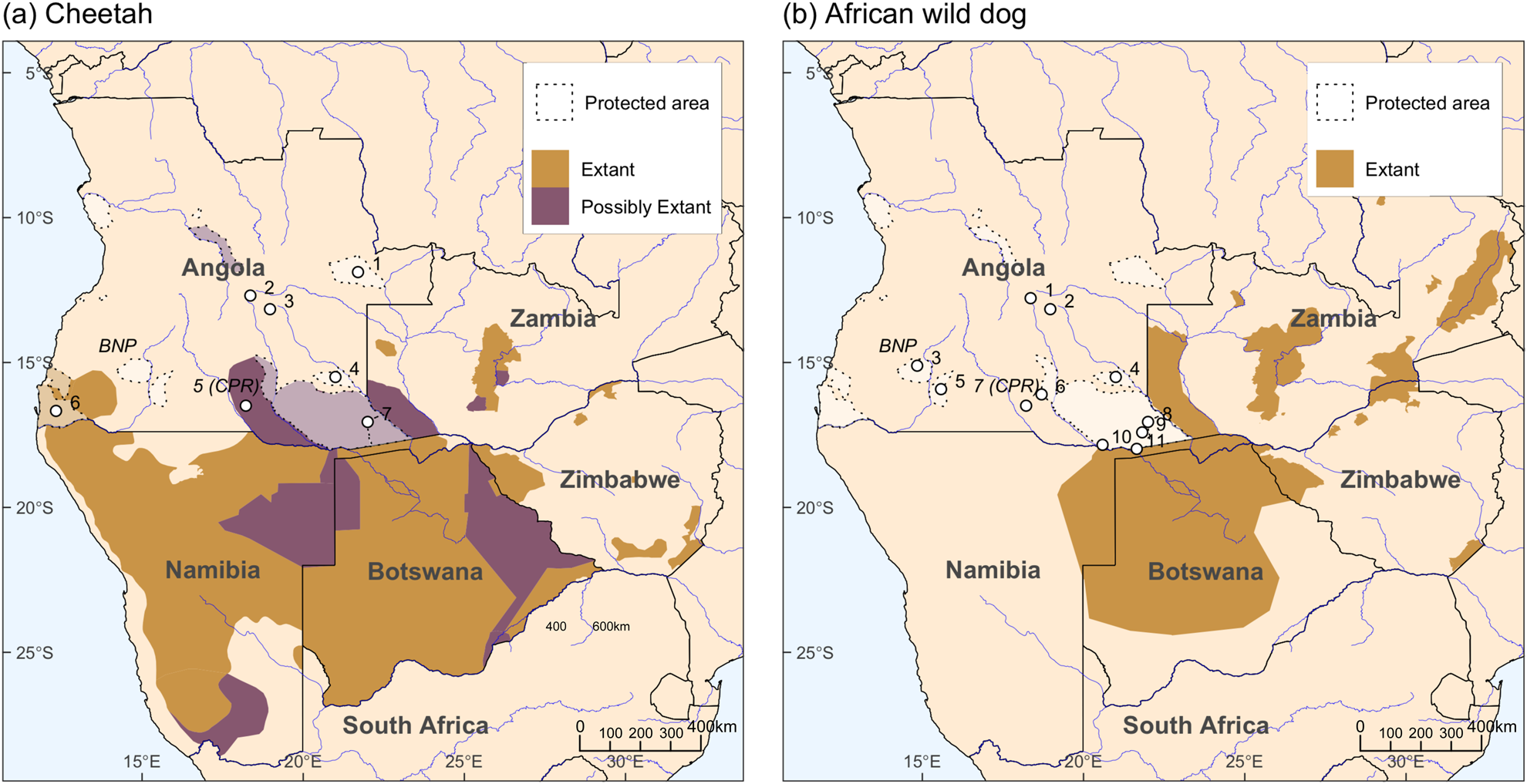

Globally, the African wild dog and cheetah are categorized as Endangered and Vulnerable, respectively, on the IUCN Red List because of population declines, range loss and the fragmentation of populations (Woodroffe & Sillero-Zubiri, Reference Woodroffe and Sillero-Zubiri2012; Durant et al., Reference Durant, Mitchell, Ipavec and Groom2015). Although historical records indicate that both species formerly occurred widely in Angola (Beja et al., Reference Beja, Pinto, Veríssimo, Bersacola, Fabiano, Palmeirim, Huntley, Russo, Lages and Ferrand2019), the majority of the country is currently classified as unknown range for both species (Fig. 1; IUCN/SSC, 2015). Updated knowledge about the distribution, abundance and population dynamics of both species, and any threats, is required for conservation planning.

Fig. 1 Distribution status (IUCN/SSC, 2015) of (a) the cheetah Acinonyx jubatus in Angola, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Botswana (Durant et al., Reference Durant, Mitchell, Ipavec and Groom2015), and of recent (2008–2018) records in Angola (1, Purchase et al., Reference Purchase, Marker, Marnewick, Klein and Williams2007; 2,3, Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Neef, Keith, Weier, Monadjem and Parker2018; 4,7, Funston et al., Reference Funston, Henschel, Petracca, Maclennan, Whitesell, Fabiano and Castro2017; 5, this study; 6, Marker et al., Reference Marker, Fabiano and Nghikembua2010, Bruce Bennett, pers. obs., 2017), and (b) the African wild dog Lycaon pictus in Angola, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Botswana (Woodroffe & Sillero-Zubiri, Reference Woodroffe and Sillero-Zubiri2012), and recent (2008–2018) records in Angola (1, BP Geological survey team, pers. obs., 2009; 2, Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Neef, Keith, Weier, Monadjem and Parker2018; 3, this study, Overton et al., Reference Overton, Fernandes, Elizalde, Groom and Funston2016, Fabiano et al., Reference Fabiano, Álvares, Kosmas, Godinho and Castro2017; 4,8, Funston et al., Reference Funston, Henschel, Petracca, Maclennan, Whitesell, Fabiano and Castro2017; 5, Overton et al., Reference Overton, Fernandes, Elizalde, Groom and Funston2016; 6, John Mendelsson, pers. obs., 2012; 7, this study; 9–11, Veríssimo, Reference Veríssimo2008). Study sites: BNP, Bicuar National Park; CPR, Cuatir Private Reserve.

Under the scope of ongoing institutional research and advanced training programmes, we surveyed c. 360 km2 in Bicuar National Park, which lies in the transition between the Angolan Miombo Woodlands and Zambezian baikiaea woodlands ecoregions (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Dinerstein, Wikramanayake, Burgess, Powell and Underwood2001) in the province of Huíla, and c. 300 km2 in Cuatir Private Reserve in western Cuando Cubango province, along the Cuatir river, one of the main tributaries of the Cubango (Okavango) river on its Angolan side, also in the Zambezian baikiaea woodlands ecoregion (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Dinerstein, Wikramanayake, Burgess, Powell and Underwood2001).

We deployed camera-trapping stations uniformly spaced at c. 2 km in the core of each study area using three camera-trap models: Hyperfire HC600 and HF2X Hyperfire 2 (Reconyx, Holmen, USA), and Cuddeback Model 1231 (Cuddeback, De Pere, USA). Fifty-one camera traps were deployed in Bicuar National Park during July 2017–June 2018 (Supplementary Fig. 1), and 43 traps in Cuatir Private Reserve during June–December 2018 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Cameras were inspected every 2 months. Additional records were obtained in Cuatir Private Reserve from unstructured surveys with six camera traps (Moultrie MP8, EBSCO Industries Inc., Birmingham, USA) during August 2013–December 2018. Additional recent records of the cheetah and African wild dog in Angola were obtained by reviewing surveys reports and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility database (GBIF, 2019; Purchase et al., Reference Purchase, Marker, Marnewick, Klein and Williams2007, Veríssimo, Reference Veríssimo2008, Marker et al., Reference Marker, Fabiano and Nghikembua2010, Overton et al., Reference Overton, Fernandes, Elizalde, Groom and Funston2016, Fabiano et al., Reference Fabiano, Álvares, Kosmas, Godinho and Castro2017, Funston et al., Reference Funston, Henschel, Petracca, Maclennan, Whitesell, Fabiano and Castro2017, Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Neef, Keith, Weier, Monadjem and Parker2018). We considered as independent any camera-trapping detections within 30 minutes, unless animals were unambiguously identified (Rich et al., Reference Rich, Davis, Farris, Miller, Tucker and Hamel2017).

In Bicuar National Park we recorded 16 independent detections of two African wild dog groups over a total of 14,232 trapping-days. We were able to assign 15 individuals to one group and three to the other. African wild dogs were detected consistently throughout the sampling period at a mean detected group size of 3.6 ± SD 2.6. No cheetahs were detected.

In Cuatir Private Reserve we obtained 13 independent detections of at least two cheetah individuals and no detections of African wild dogs over a total of 5,173 trapping-days of systematic surveying. Unstructured camera trapping provided records of an individual cheetah in July 2014, and a coalition of two male cheetahs in October 2017. We were not able to match any of these cheetahs with those of the 2018 survey. A group with ≥ 4 African wild dog individuals was detected in July, August and October 2014, and another of ≥ 5 individuals in October 2016.

Our findings build on recent surveys that indicate the occurrence of cheetahs and African wild dogs in Luengue-Luiana and Mavinga National Parks (Funston et al., Reference Funston, Henschel, Petracca, Maclennan, Whitesell, Fabiano and Castro2017), and in the Cuanavale and Cuito river catchments (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Neef, Keith, Weier, Monadjem and Parker2018; Fig. 1). African wild dogs have also been observed in Bicuar National Park by Overton et al. (Reference Overton, Fernandes, Elizalde, Groom and Funston2016) and Fabiano et al. (Reference Fabiano, Álvares, Kosmas, Godinho and Castro2017), and in Mupa National Park (Overton et al., Reference Overton, Fernandes, Elizalde, Groom and Funston2016) and Mucusso Reserve (Veríssimo, Reference Veríssimo2008), and cheetahs in and around Iona and Cameia National Parks (Purchase et al., Reference Purchase, Marker, Marnewick, Klein and Williams2007; Marker et al., Reference Marker, Fabiano and Nghikembua2010). We found no records of cheetahs or African wild dogs for 2008–2018 in Angola in the Global Biodiveristy Information Facility.

Our findings indicate that the African wild dog's range as currently delimited (IUCN/SSC, 2015), should be extended c. 750 km further west-north-west from the Angolan/Namibian border, beyond the Cunene river and including Bicuar National Park. As the species has been regularly detected in the Park since at least 2015, this complies with IUCN/SSC (2015) criteria as an area of African wild dog residency, with groups of ≥ 10 individuals and breeding confirmed through multiple observations of groups with pups, made by park rangers in 2016 (Overton et al., Reference Overton, Fernandes, Elizalde, Groom and Funston2016; Fabiano et al., Reference Fabiano, Álvares, Kosmas, Godinho and Castro2017). It is likely that other large extents of good quality habitat in Angola also harbour resident populations, and further monitoring to assess presence and residency status are required. Cheetahs have been observed regularly in the lower Angolan range of the Cubango river, and also in south-eastern, south-western and central-eastern Angola in the provinces of Namibe, Cuando Cubango and Moxico (Marker et al., Reference Marker, Fabiano and Nghikembua2010; Funston et al., Reference Funston, Henschel, Petracca, Maclennan, Whitesell, Fabiano and Castro2017; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Neef, Keith, Weier, Monadjem and Parker2018; Fig. 1). These reports suggest that IUCN's classification of the south-western Angolan range for the cheetah should be changed from Possibly Extant to Extant.

Our findings will support the new political willingness in Angola to invest in wildlife conservation strategies and will help to unlock conservation funding for the cheetah, African wild dog and other carnivores. Given that the majority of the distribution of these two species potentially falls outside protected areas where they are more susceptible to anthropogenic threats, we emphasize the urgency of identifying remnant populations in Angola and quantifying any threats to the species.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Instituto Nacional da Biodiversidade e Áreas de Conservação for permits, José Maria Kandungo for logistic support in Bicuar National Park, Fernando Calunga and park rangers Fernando Tchacaca, Tchimbuale Cambuta, Ombili, José Manuel Tchipuapua and José Maria Alves for their assistance during fieldwork, and Bruce Bennett for data sharing in Iona National Park. PM was supported by UID/BIA/50027/2019 with funding from FCT/MCTES through national funds. FR, SK and RG were supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (PD/BD/114030/2015, PD/BD/142825/2018, IF/00564/2012). TM and MC were supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research SASSCAL project (PN 01LG1201 M). This research was conducted within the UNESCO Chair Life on Land.

Author contributions

Study design: PM, RG; fieldwork: all authors; data analysis: PM, FR; writing: PM, with inputs from all authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.