Introduction

Ivory from African Loxodonta spp. and Asian elephants Elephas maximus has been traded for centuries (Kunz, Reference Kunz1916; Ibn Muḥammad Ibrāhīm, 1972; Feinberg & Johnson, Reference Feinberg and Johnson1982; Fine Arts Department, 2013). Although Asian elephant ivory is less valuable than African ivory (St. Clair & Mclachlan, Reference St. Clair and Mclachlan1989), it is still highly valued and has been a source of income in Thailand for hundreds of years. Records can be traced back to the 14th and 15th centuries, with trade involving merchants from India, China, and Arabian and European countries (Ibn Muḥammad Ibrāhīm, 1972; Pallegoix, Reference Pallegoix and Tips2000; Fine Arts Department, 2013). During the 17th–19th centuries ivory was used to make musical instrument parts, art objects and high-value decorative items (Kunz, Reference Kunz1916; Johnson, Reference Johnson1978; Feinberg & Johnson, Reference Feinberg and Johnson1982; Walker, Reference Walker2009). Carved products, made from imported raw ivory, were exported to Western and South-east Asian countries during 1800–1850 (Fine Arts Department, 2013). After World War II, the predominant global destinations for ivory products shifted from Europe to Asia (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay1986). Ivory markets in China and Thailand expanded significantly in the late 1980s and 1990s, coinciding with the development of regional economies and tourism in Asia (Stiles, Reference Stiles2004, Reference Stiles2009).

This significant global growth in demand for ivory led to increased killing and consequently population declines of African elephants (Wittemyer et al., Reference Wittemyer, Northrup, Blanc, Douglas-Hamilton, Omondi and Burnham2014), and in 1989 the African elephant was uplisted from CITES Appendix II to Appendix I (CoP7 Prop.26, 1989; Sukumar, Reference Sukumar2003). All Asian and most African elephants are currently listed in CITES Appendix I, and international commercial trade in their ivory is therefore banned (CITES, 1973, 2019a). Trade in ivory from African elephants listed in CITES Appendix II (populations from South Africa, Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe) is permitted under strict conditions (CITES, 2019a). Penalties for non-compliance with CITES regulations are harsh, and offending states face sanctions in the form of suspension of all international trade of any CITES-listed animal and plant species (CITES, 1973).

Thailand had high levels of illegal ivory trade during 2009–2011, largely because it lacked effective legal provisions to control trade in ivory sourced from the country's captive elephants or to criminalize illegally sourced ivory from Africa (CoP16 Doc. 53.2.2 (Rev. 1), 2013). As a result, CITES recommended sanctioning Thailand by 31 March 2015 if it did not undertake satisfactory action to address this illegal ivory trade (SC65 Com. 7, 2014). This prompted a revision of Thailand's National Ivory Action Plan, including legislative reforms through the new Elephant Ivory Act (2015), to regulate trade in locally sourced ivory, and the listing of the African elephant as a protected species (SC66 Doc.29 Annex 8, 2015). These reforms facilitated comprehensive monitoring of the ivory trade and allowed authorities to address the illegal trade in African ivory. The resulting significant decrease in the domestic ivory market, together with large-scale seizures of smuggled ivory, eventually enabled Thailand to exit the National Ivory Action Plans Process (SC70 Sum. 2 (Rev. 1), 2018). Nonetheless, as a country with a domestic ivory trade, Thailand continues to be bound to implement the Resolution of the Conference of the Parties 10.10 (CITES, 2019b). Requirements include control of the domestic market to prevent illegal activities related to the international ivory trade, and recommendations to close the legal domestic ivory trade if it involves illegal activities in other countries (CITES, 2019b).

Our review draws on peer-reviewed and grey literature to describe the challenge of sustainably managing elephants and ivory in Thailand, where such management is driven by a complex mix of cultural, livelihood and conservation values, and where there is a discrepancy between domestic needs and international obligations. We discuss the challenges of implementing the laws related to elephants and ivory in Thailand, and make recommendations to inform future conservation management.

Elephants in Thailand: past and present

Since the 13th century, Thai people have captured wild elephants and taken advantage of their strength and resilience for transportation, farm and forestry work (Pravorapakpibul, Reference Pravorapakpibul1961; Ibn Muḥammad Ibrāhīm, 1972; Pallegoix, Reference Pallegoix and Tips2000; Fine Arts Department, 2013). Elephants were in historical times also used to administer punishments, either to frighten offenders or execute criminals (Ibn Muḥammad Ibrāhīm, 1972). The establishment of the Elephant Department during the early Ayutthaya period (1420s) reflected the importance of elephants in warfare (Pravorapakpibul, Reference Pravorapakpibul1961; Fine Arts Department, 2013); during this time, kings went to battle on the backs of elephants (Fine Arts Department, 2013), and there is still a unit under the Royal Office responsible for royal elephants (Fine Arts Department, 2013). From the 1600s onwards trained elephants were exported, largely to India (Pallegoix, Reference Pallegoix and Tips2000; Fine Arts Department, 2013). Trade in both elephants and ivory was permitted under the King's administration until the initial period of Thailand's Rattanakosin Era in the early 1800s (De La Loubère, Reference De La Loubère1969; Fine Arts Department, 2013). With technological advancements, the use of elephants as draught animals began to decline. Captive elephants in Thailand are now largely used in tourism (Phuangkum et al., Reference Phuangkum, Lair and Angkawanith2005), but they still hold considerable cultural value (Fine Arts Department, 2013). There are estimated to be c. 3,800 captive and nearly 3,500 wild Asian elephants in Thailand (Ministry of Environment and Forestry, 2017; DNP, 2020).

In 1998 the Thai government designated 13 March as Thai Elephant Day, and in 2001 the Asian elephant was officially declared to be the national animal, to recognize the species’ significance for the country's monarchy, history and culture (Office of the Prime Minister, 1998, 2001; Fine Arts Department, 2013). Elephants with distinctive characteristics (e.g. exceptionally pale or darker skin than usual) are legally recognized as so-called auspicious elephants and are required to be presented to the King under the Wild Elephant Protection Act B.E. 2464 (1921). Auspicious elephants are a symbol of the power and authority of the King as a divine God, bringing propitiousness and agricultural productivity, and were also traditionally used for royal transport (Fine Arts Department, 2013). Religious beliefs include the reincarnation of the Buddha as a white elephant (Sukumar, Reference Sukumar2003). In addition, elephants have been depicted in various official symbols, including the national flag used during 1817–1917, with a white elephant in the centre of a red flag (Fine Arts Department, 2013). The Kui people regard knowledge about elephants as an important part of ethnic identity and a component of Thailand's cultural heritage (Ministry of Culture, 2018).

The oldest ivory artefacts in Thailand date to almost 4,000 BCE (Na Nakhonphanom, Reference Na Nakhonphanom2013). Ivory carving was among the traditional Thai art forms dated from the Ayutthaya era. Later, Rattanakosin's Kings established a department producing traditional art pieces and utilities, including ivory carving, for royal use (Teanpewroj, Reference Teanpewroj2015). Ivory has also been kept in temples for worship, and presented to revered persons, as some Thai people believe a supernatural spirit protects elephants (Bangkok Biz News, 2014). A pair of polished tusks, mounted on wooden bases, is often kept in Thai houses, near altar-tables or in meditation areas. A recent survey indicated that 2–3% of Thai people are ivory consumers, with ivory purchases often tied to the belief in its supernatural benefits (USAID Wildlife Asia, 2018). Jewellery is the most common ivory product found in Thai markets, followed by sacred objects and decorative items, with individual items priced at THB 500–80,000 (USD 15–2,540; USAID Wildlife Asia, 2018; Bank of Thailand, 2019).

Commercial ivory carving probably began in the late 1930s at Phayuhakhiri in Nakhon Sawan province in central Thailand, to satisfy the demand for worship items blessed by revered monks. Carvings included Buddha amulets, knives with ivory sheaths and handles, and animal figurines (Stiles, Reference Stiles2003, Reference Stiles2009). With the growth of tourism in Thailand in the 1970s, manufacturing shifted to products desired by foreigners such as jewellery, East Asian figurines and utilities, and expanded to adjacent areas (Stiles, Reference Stiles2003). People in Uthai Thani, a nearby province, specialize in making steel and silver products decorated with ivory, and in Manorom in Chai Nat province, south of Phayuhakhiri, people carve Singha (lion figurines) and other sacred items (Stiles, Reference Stiles2009). In the north-east, Thatum in Surin province has many captive elephants, and traditional knowledge about elephants and their training has been passed down many generations of Kui people (Chomdee et al., Reference Chomdee, Oadjessada, Submak, Saendee, Lem-ek, Chanpoom and Hongthong2013). In the past, raw ivory was mainly privately kept or sold as sacred items. Historically, some ivory was carved into Buddha figurines, but since the 2000s, commercial carving into a wide range of jewellery has become common in Thatum, to meet market demand.

Captive Asian elephants are a source of ivory in Thailand and other Asian countries such as Myanmar and Lao PDR (Sukumar, Reference Sukumar2003; Vigne & Martin, Reference Vigne and Martin2017, Reference Vigne and Martin2018). In the past, the tusks of captive elephants were not usually cut, as the animals were left to roam freely in forests during periods when they were not required for work. There, the elephants used their tusks for defence, foraging and digging, which naturally shortens the tusks (Vanapithak, Reference Vanapithak1995; Sukumar, Reference Sukumar2003). Now most captive elephants have less access to forests and limited use for their tusks. This can lead to tusks growing overly long or crossing over at the tips, which needs management for animal welfare reasons. Tuskers also face the risk of being killed or injured by ivory poachers. Prominent tusks are mainly produced by male elephants and grow throughout life (Sukumar, Reference Sukumar2003), by c. 17 cm per year (Phuangkum et al., Reference Phuangkum, Lair and Angkawanith2005). Tusks of live elephants are usually trimmed every 2–3 years from 15 years of age (Stiles, Reference Stiles2009), and whole tusks are removed from dead individuals (Phuangkum et al., Reference Phuangkum, Lair and Angkawanith2005; Stiles, Reference Stiles2009; Chomdee et al., Reference Chomdee, Oadjessada, Submak, Saendee, Lem-ek, Chanpoom and Hongthong2013).

Since the legislative reform in January 2015, the ivory trade in Thailand appears to be in decline. Whereas 339 shops trading ivory were identified prior to the January 2015 legislative reform, this number decreased to 117 by 2018 (SC66 DOC. 29 ANNEX 8, 2015; SC70 Doc 27.4 Annex 21, 2018), and the quantity of products offered for sale in physical shops also decreased (Krishnasamy et al., Reference Krishnasamy, Milliken and Savini2016). However, the online trade is of concern and requires better regulation and law enforcement (Krishnasamy et al., Reference Krishnasamy, Milliken and Savini2016; WWF-Thailand, 2016). The shrinking of the ivory business is also evident in the decreasing number of active ivory craftsmen, mainly in Phayuhakhiri, one of the most important locations for the manufacturing of ivory products: there were an estimated 50–100 ivory carvers in 1989, but only 50–60 in 2008 (Stiles, Reference Stiles2009). In the early 2000s, prior to the disruption of the illegal ivory trade by the Thai government in Phayuhakhiri, ivory carvers received a daily income of c. TBH 1,000–2,000 (USD 32–64). As trade restrictions reduced the demand for ivory carvings, some carvers began to work with other materials (e.g. wood, cattle and ostrich bones), and others ceased carving entirely (MGR Online, 2018). The switch from ivory to cattle bone reduced the income of carvers by a mean of 35% (Stiles, Reference Stiles2003). In addition to the immediate effects on income, there is concern about the loss of the cultural knowledge of ivory carving (Stiles, Reference Stiles2003).

Elephant protection in Thailand

Elephant protection in Thailand (Fig. 1) dates back to the 17th century, when Thai people were permitted to capture, but not kill, wild elephants (De La Loubère, Reference De La Loubère1969). Early legal provisions were designed to protect privately owned elephants (Draught Animals Act R.E.110, 1891), and included registration requirements, identification documents and import/export records. These measures are still in place (Draught Animals Act B.E. 2482, 1939; Pravorapakpibul, Reference Pravorapakpibul1961, Reference Pravorapakpibul1962).

Fig. 1 Timeline of the legal status of elephants in Thailand. The timeline shows distinctive periods in the developing legal status of elephants. Asian elephants Elephas maximus have been considered as draught animals since 1891 (captive Asian elephant), and identification documents for elephants were employed more than a decade earlier. Regulations related to the capture of wild Asian elephant were prescribed by enactment of the Wild Elephant Protection Act R.E. 119 (1900). The wild Asian elephant has been protected under the Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act (WARPA) since 1975, although hunting of all wildlife in protected areas has been prohibited upon the issuance of WARPA in 1960. The Act later included the African elephant Loxodonta africana in the category of protected animal, and this species now receives the same protection as the wild Asian elephant.

Wild elephants are mainly protected by the Wild Elephant Protection Act and the Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act (WARPA). The former specifically imposes measures to protect wild Asian elephants such as controlling capture and procedures related to auspicious elephants (Wild Elephant Protection Act R.E. 119, 1900; Wild Elephant Protection Act B.E. 2464, 1921). The latter involves regulations concerning wildlife generally, and wildlife parts and products. It also prohibits hunting of any animals in protected areas (Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act B.E. 2503, 1960; Announcement of the National Executive Council No., 228, 1972; Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act B.E. 2535, 1992; Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act (No. 3) B.E. 2557, 2014; Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act B.E. 2562, 2019).

Wild Asian elephants have been protected under WARPA since 1975, with a complete ban on commercial uses since 1992 (Ministerial Regulation No. 10 (B.E. 2518) issued under the Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act B.E. 2503, 1975; Ministerial Notification on prescribing possession limit of protected animals according to the Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act B.E. 2503, 1976; Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act B.E. 2535, 1992; Ministerial Regulation No. 4 (B.E. 2537) issuing under the Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act B.E. 2535, 1994). In 2015, the African elephant was the first non-native species to be added to the list of protected animals under WARPA (Ministerial Regulation on prescribing protected animals (No. 3) B.E. 2558, 2015). The Act does not apply to animals protected by the Draught Animals Act, including captive Asian elephants (Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act B.E. 2535, 1992). It was amended in 2019 to increase penalties and extend control over the possession and domestic trade of CITES-listed species (Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act B.E. 2562, 2019).

Thai laws currently categorize elephants into three groups: captive Asian elephants (draught elephants and their offspring) are registered as draught animals under the Draught Animals Act, whereas wild Asian elephants and African elephants are protected species under WARPA (see Supplementary Table 1 for details).

Legal framework for the regulation of ivory possession and trade

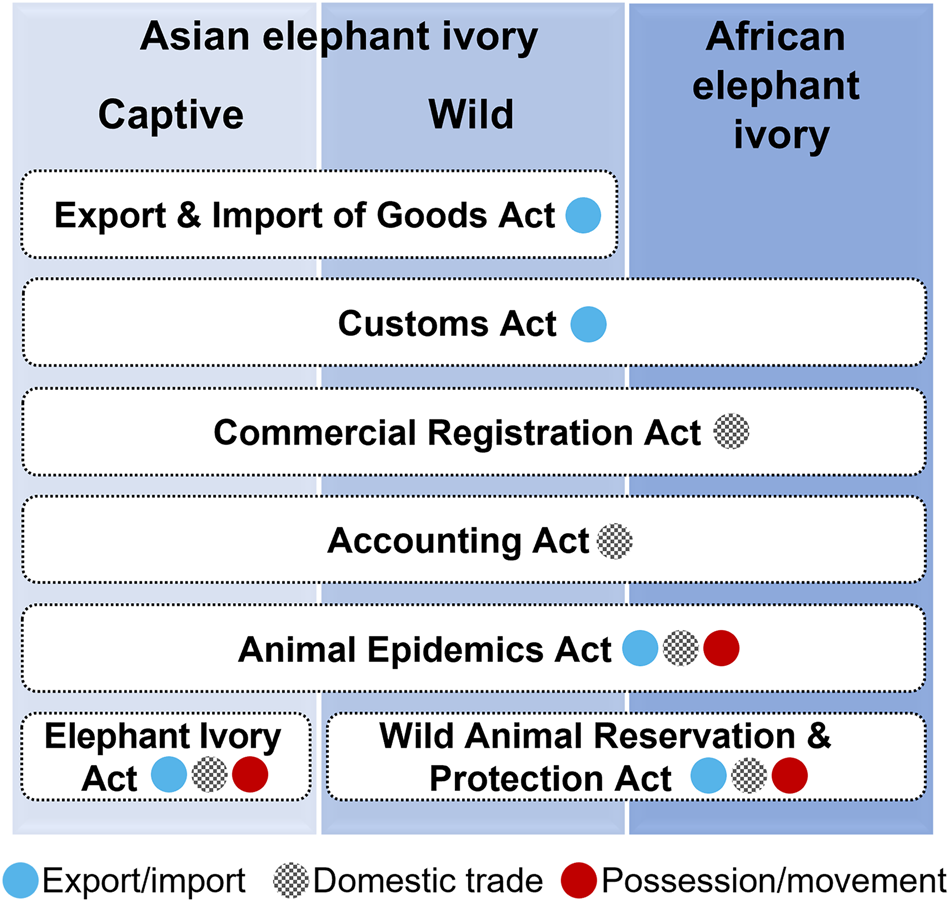

Current regulations regarding the transport, possession, domestic trade, import and export of elephant ivory in Thailand are complex and reflect the differences in the legal status of the three categories of elephants (Fig. 2). Although WARPA (2019) and the Elephant Ivory Act (2015) are the major laws controlling activities related to ivory, there are six additional laws that require enforcement by five authorities from four ministries (Supplementary Table 1). Members of the Royal Thai Police also serve as enforcement officers under the two main acts. In addition, in 2013 the illegal exploitation of natural resources for commercial purposes (including ivory-related activities) was included as a case offense under the Money Laundering Control Act B.E. 2542 (1999), thereby allowing proceedings for asset forfeiture in addition to prosecution under the main laws (Money Laundering Control Act (No. 4) B.E. 2556, 2013). Illicit export or export of ivory may also result in prosecution under the Prevention and Suppression of Involvement in Transnational Crime Organization Act B.E. 2556 (2013).

Fig. 2 The complexity of current legislation for the three types of ivory in Thailand. Activities relating to ivory from captive Asian elephants are mainly regulated by the Elephant Ivory Act and five supportive laws. Activities involving ivory of wild Asian and African elephants are governed by six and five pieces of legislations, respectively. Both species are protected under WARPA, but export regulations under the Export and Import of Goods Act are only applied to Asian elephants. Regulations concerning key activities such as possession, transport, domestic trade, export and import vary among ivory types.

The Elephant Ivory Act B.E. 2558 (2015) requires ivory to be registered, with information including evidence of ivory acquisition (i.e. a certificate of origin for elephant ivory issued by registrars of the Draught Animals Act; DNP, 2017). People who possess ivory must notify the relevant official of changes in ownership, place of possession and ivory modification or manufacturing. Inter-provincial movement of raw ivory also requires a permit, upon presentation of the certificate of origin for elephant ivory, according to the Animal Epidemics Act B.E. 2558 (2015). Trade in ivory is controlled by at least three different laws: (1) permission and compliances under the Elephant Ivory Act (2015) (Ministerial Regulation on application, permission, trade and suspension or revocation of ivory trade permit B.E. 2558, 2015), (2) registration under the Commercial Registration Act B.E. 2499 (1956) (Notification of the Ministry of Commerce on registration requirement of businesses (No. 8) B.E. 2547, 2004), and (3) account keeping under the Accounting Act B.E. 2547 (2000) (Notification of Ministry of Commerce on prescribing the duty of accounts maintenance for ivory-related entrepreneurs B.E. 2551, 2008). A trade permit under the Animal Epidemics Act B.E. 2558 (2015) is also required if trade involves raw ivory.

Permits are required by law for the export and import of all three types of ivory; however, permission is granted only for non-commercial purposes. Import and export permits are required under the Elephant Ivory Act B.E. 2558 (2015) for the ivory obtained from draught elephants, and WARPA permits are mandatary for ivory from wild Asian and African elephants (Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act B.E. 2562, 2019). In addition, the export of Asian elephants (both wild and captive), including their parts and derivatives, requires a permit under the Export and Import of Goods Act B.E. 2522 (1979) (Notification of the Ministry of Commerce on specifying elephant as a goods required a license prior to export B.E. 2555, 2012). All elephants are also governed by the Animal Epidemics Act B.E. 2558 (2015), and export and import permits are required for raw elephant ivory. Given the legal provision of ivory, import and export of all ivory types must also comply with the Customs Act B.E. 2560 (2017).

Discussion

The global ivory trade

The ivory trade is an example of the tension between international and national efforts to conserve species important in wildlife trade. Elephant ivory is a long-standing and controversial agenda item in the CITES forum because member states have different perspectives and needs, arguing either for a ban on or the legalization of ivory trade. Prior to African elephants being transferred to CITES Appendix I, southern African nations unilaterally argued against a ban on the commercial trade of African ivory. Their rationale was that they already employed practices for managing overabundant elephant populations and that these practices provided both ecological balance and economic benefit (Stiles, Reference Stiles2004). Elephants from countries with healthy populations were later transferred to Appendix II to facilitate sustainable conservation practices (CITES, 1997, 2000).

However, the legalization of some ivory trade has raised concerns about demand stimulated by the legal trade, complication of enforcement efforts, and the link to poaching and the illegal ivory trade. This has led to calls for the total closure of the legal trade (Stiles, Reference Stiles2004; CoP17 Doc. 57.2, 2016; Dasgupta, Reference Dasgupta2016; Aryal et al., Reference Aryal, Morley and McLean2018). The commercial domestic trade of ivory has been prohibited in some countries that have no access to locally supplied ivory (e.g. USA, China, UK); Hong Kong and Taiwan have also announced plans to end their domestic ivory trade (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, 2016; Kao, Reference Kao2018; Morgan, Reference Morgan2018; Department for Environment, 2019). The 2016 IUCN conference accepted the resolution calling for governments to close their domestic markets for commercial trade in raw or worked elephant ivory (IUCN, 2016). Most member countries voted for a non-legally binding motion to close the domestic ivory trade, whereas Japan, Namibia and South Africa, all countries with regulated domestic markets, argued for continued regulation (Dasgupta, Reference Dasgupta2016). The United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution to reinforce the need to secure legal domestic markets, and implement Resolution of the Conference of the Parties 10.10 of CITES to close legal domestic ivory markets, as a matter of urgency, if these markets contribute to poaching or illegal trade (UNGA A/71/L.88, 2017). Countries with active domestic ivory markets, including Thailand, are still being pressured to close them (WWF-Thailand, 2016; Kent, Reference Kent2019).

The domestic ivory trade

In circumstances such as those in Thailand, ivory could be treated as a renewable resource, the sustainability of which is achieved through a highly regulated legal trade. The Thai ivory trade, based on a supply of raw material obtained from captive elephants, has the potential to be sustainable, support local craftsmen and maintain traditional knowledge of ivory carving. Elephant tusks grow throughout the animal's life (Sukumar, Reference Sukumar2003) and can be harvested with non-lethal methods from captive elephants; there is thus the potential to provide a renewable resource to supply the domestic ivory trade. At the first national registration in 2015, c. 160 t of raw ivory were held by private individuals in Thailand (Krishnasamy et al., Reference Krishnasamy, Milliken and Savini2016). The captive elephant population in the country produces c. 300–400 kg of ivory annually (Stiles, Reference Stiles2009), providing an additional income for elephant owners (Chomdee et al., Reference Chomdee, Oadjessada, Submak, Saendee, Lem-ek, Chanpoom and Hongthong2013). Effective legal enforcement prevents the entry of illegally sourced ivory, increasing the value of legal sources of ivory (Stiles, Reference Stiles2009). An ivory shop owner stated that the price of elephant tusks is TBH 40,000–60,000/kg (USD 1,300–1,900/kg; S. Arbhassarosakul, pers. comm., 2018), a considerable increase from prices in 2001 (USD 100–250/kg; Stiles, Reference Stiles2009). Ivory carving also creates income for craftspeople: a master carver can earn up to USD 1,000 for a 1-inch elaborate Singha, with the ivory itself comprising < 10% of the price (S. Arbhassarosakul, pers. comm., 2020).

Given that the legal ivory trade in Thailand requires a supply from local captive Asian elephants, the domestic ivory trade could be sustainable if locally sourced ivory can satisfy local demand. Understanding the nature of local consumption would provide a reference for evaluating the capacity of local ivory stock to meet this demand.

Overcoming the barriers to sustainable domestic ivory trade

The reformed Thai legislation regarding ivory has the potential to align with the principles of the CITES convention and Thailand's economic interests and cultural values, if barriers to enforcement can be overcome. However, the complex nature of current legislation regarding ivory-related activities makes compliance difficult. For example, the way in which certificates of ivory origin are issued, and the implementation of relevant regulations, largely depend on the legal understanding of local registrars (S. Arbhassarosakul, pers. comm., 2018). The permit for inter-provincial movement under the Animal Epidemics Act is issued only after the presentation of a certificate of origin. However, certificates cannot be issued retrospectively, which makes interprovincial movement of old stocks of ivory (pre-2015) impossible. The need to visit a regional office to register ivory possession presents barriers in the form of travel costs and time, an effort that is difficult to justify particularly for small ivory items (S. Arbhassarosakul, pers. comm., 2018). For ivory traders, certain legal requirements posed by the Accounting law and Elephant Ivory Act create a procedural burden. There is thus a need to streamline the legal framework and consolidate laws related to elephants and ivory, which would not only reduce the administrative effort for traders, but also facilitate product registration for buyers, thereby contributing to increased compliance.

Legal domestic ivory markets that contribute to poaching or illegal trade need to be closed as a matter of urgency (CITES, 2019b). Enforcement efforts are thus essential for maintaining a closed Thai domestic market, as the activity of illegal businesses is directly influenced by the effectiveness of law enforcement. Comprehensive trade controls should prevent both the entry of illegally sourced ivory into the domestic market and the export of ivory products from the country. Significant effort is required to monitor online trade, because illegal online commerce could hamper the control of the legal trade. The new WARPA can facilitate the prosecution of people involved in the illegal online trade of ivory (Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act B.E. 2562, 2019). The use of electronic databases and software systems could help monitor the trade and enable information exchange amongst relevant authorities.

Ivory identification is a challenge for enforcement officers, and the use of modern technologies could facilitate this. Considering the three types of ivory covered by Thai laws, practical tools to differentiate between them are needed to ensure effective control of the ivory trade. Samples of DNA from captive elephants (SC70 Doc 27.4 Annex 21, 2018) would facilitate verification of ivory from captive individuals. Advances in technology (e.g. analysis of chemical composition and genetics) potentially offer methods for distinguishing ivory from different species and locations, based on diet, habitat use and genetics (Raubenheimer et al., Reference Raubenheimer, Brown, Rama, Dreyer, Smith and Dauth1998; Shimoyama et al., Reference Shimoyama, Morimoto and Ozaki2004; Wasser et al., Reference Wasser, Clark, Drori, Kisamo, Mailand, Mutayoba and Stephens2008; Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Merker, Streit, Boner and Jacob2016). Spectroscopic techniques could offer simple and non-destructive ways to assist field officers in identifying ivory (Shimoyama et al., Reference Shimoyama, Morimoto and Ozaki2004; Buddhachat et al., Reference Buddhachat, Thitaram, Brown, Klinhom, Bansiddhi and Penchart2016). Isotopic analyses are effective in differentiating between wild and captive animals of the same species such as wolves Canis spp. and pythons Python spp. (Kays & Feranec, Reference Kays and Feranec2011; Natusch et al., Reference Natusch, Carter, Aust, Van Tri, Tinggi and Mumpuni2017). The development of practical techniques for distinguishing ivory from captive elephants from that originating from illegal sources would strengthen the enforcement capacity of Thai authorities (Chaitae et al., Reference Chaitae, Rittiron, Gordon, Marsh, Addison, Pochanagone and Suttanon2021).

Conclusion

The historical relationship between elephants and culture influences the legal framework regarding elephants and ivory in Thailand. Thai laws allow the exploitation of captive elephants and ivory as private assets, although the country is bound by CITES provisions for international activities. Compared to the situation pre-2015, the laws now enable comprehensive control of the domestic trade in ivory. However, the complexity of the legal system presents barriers to effective implementation. The administrative effort to comply with legal requirements appears to result in small-scale ivory traders abandoning the trade. These complexities also discourage compliance and hamper law enforcement. Integration of all relevant regulations into a single law governing live elephants, their parts and products would facilitate effective implementation. A sustainable ivory industry in Thailand would benefit local economies and livelihoods, without compromising the conservation of elephants.

Acknowledgements

Funding was received from the Thai government for AC's PhD studies at James Cook University.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, writing: AC; revisions: JA, IG, HM.

Conflicts of interest

AC is an officer in Thailand's Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation. The other authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.