Introduction

The tiger Panthera tigris has suffered catastrophic declines in its population (96%) and habitat (95%) over the past century (Nowell & Jackson, Reference Nowell and Jackson1996; Goodrich et al., Reference Goodrich, Lynam, Miquelle, Wibisono, Kawanishi and Pattanavibool2015; Wolf & Ripple, Reference Wolf and Ripple2017). Evidence suggests only 42 source sites (i.e. sites with breeding populations that have the potential to support future recovery of the tiger over a larger area) remain across the species’ range, totalling 90,000 km2 (5.9% of current range; Walston et al., Reference Walston, Robinson, Bennett, Breitenmoser, Da Fonseca and Goodrich2010). Habitat loss has been particularly acute in South and South-east Asia, with a 41% reduction from 1996 to 2006 (Sanderson et al., Reference Sanderson, Forrest, Loucks, Ginsberg, Dinerstein and Seidensticker2006) and an estimated forest loss of 71,134 km2 in priority tiger conservation landscapes from 2001 to 2014 (Joshi et al., Reference Joshi, Dinerstein, Wikramanayake, Anderson, Olson and Jones2016).

The Indochinese tiger Panthera tigris corbetti is one of six extant tiger subspecies and is categorized as Endangered on the IUCN Red List (Lynam & Nowell, Reference Lynam and Nowell2011; Goodrich et al., Reference Goodrich, Lynam, Miquelle, Wibisono, Kawanishi and Pattanavibool2015). It was historically distributed throughout most of mainland South-east Asia (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Kim, Johnson, van der Walt, Martenson and Yuhki2004, Reference Luo, Liu and Xu2019) across Cambodia, Lao, Myanmar, southern China, Thailand and Viet Nam (Lynam, Reference Lynam2010). Evidence suggests three range countries (Cambodia, Lao and Viet Nam) have lost viable populations, and the Indochinese subspecies may qualify for Critically Endangered status (Lynam & Nowell, Reference Lynam and Nowell2011). Despite previous evidence of a viable breeding population in Nam Et Phou Loey National Protected Area in Lao (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Vongkhamheng, Hedemark and Saithongdam2006; Vongkhamheng, Reference Vongkhamheng2011), recent evidence suggests tigers may have been extirpated from the country (Rasphone et al., Reference Rasphone, Kéry, Kamler and Macdonald2019). Tigers are probably extinct in Cambodia, prompting plans for reintroduction (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Crouthers, Ramesh, Vattakaven, Borah and Pasha2017), and in Viet Nam there have been no confirmed tiger records in > 20 years (Lynam & Nowell, Reference Lynam and Nowell2011). A paucity of reliable population data in current range countries has obscured these declines (Lynam & Nowell, Reference Lynam and Nowell2011), and information on remaining populations is needed urgently.

It is possible that the only remaining source sites for the Indochinese tiger are in Myanmar and Thailand. However, studies in key landscapes in Myanmar have documented low and potentially declining numbers (Lynam et al., Reference Lynam, Rabinowitz, Myint, Maung, Latt and Po2009; Rao et al., Reference Rao, Htun, Zaw and Myint2010; Naing et al., Reference Naing, Ross, Burnham, Htun and Macdonald2019; Moo et al., Reference Moo, Froese and Gray2018) reinforcing the importance of Thailand as the tiger's last stronghold in the region. In Thailand's 2010 action plan, the national tiger population was estimated to be 190–250 individuals (Pisdamkam et al., Reference Pisdamkam, Prayurasiddhi, Kanchanasaka, Maneesai, Simcharoen and Pattanavibool2010). A recent, updated government report included landscape-specific population estimates of at least 101–128 individuals (DNP, 2016), with potentially only two viable populations, in the Western Forest Complex (25,000 km2) and the Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex (6,155 km2) in eastern Thailand.

Although a number of tiger-focused studies have been conducted in other parts of Thailand, including ongoing monitoring in the Western Forest Complex (Duangchantrasiri et al., Reference Duangchantrasiri, Umponjan, Simcharoen, Pattanavibool, Chaiwattana and Maneerat2016), data from the Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex are limited. Information on tigers there has originated primarily from general assessments of faunal communities or other carnivores, or from interviews and personal communications (Lynam, Reference Lynam2001; Kanwatanakid et al., Reference Kanwatanakid, Lynam, Galster, Chugaew, Kaewplung and Suckaseam2002; Lynam et al., Reference Lynam, Round and Brockelman2006; Jenks et al., Reference Jenks, Chanteap, Damrongchainarony, Cutter, Cutter and Redford2011). Evidence suggests that tigers may have been extirpated in Khao Yai National Park, but almost no information is available from other areas in this forest complex. To our knowledge, there have been no studies focusing on tigers across this forest complex in its entirety. Comprehensive studies on prey species, an important factor for tiger distribution and persistence (Karanth & Stith, Reference Karanth, Stith, Seidensticker, Jackson and Christie1999; Karanth et al., Reference Karanth, Nichols, Kumar, Link and Hines2004), are also lacking.

Given catastrophic population and range declines elsewhere in Thailand and South-east Asia, knowledge of the tiger population of the Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex is of national, regional and global importance. Here, we describe results from the first camera-trap study focused on tigers and implemented across all protected areas in this landscape, conducted during 2008–2017. We aimed to assess tiger and prey populations and to identify any patterns in detection frequencies of tigers and prey species amongst protected areas. Our findings provide baseline information for tigers and their prey, and also document potentially important information on other mammal species of research and conservation interest.

Study area

The Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex lies c. 160 km north-east of Bangkok (Fig. 1). To the east it partially borders the international boundary between Thailand and north-west Cambodia. The terrain is hilly, with altitudes of 100–1,351 m. The forest complex consists of five protected areas: Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary, Khao Yai National Park, Pang Sida National Park, Thap Lan National Park and Ta Phraya National Park (DNP, 2004). These parks are collectively inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List (UNESCO, 2017).

Fig. 1 Survey locations in the Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex, which includes five protected areas: Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary, Khao Yai National Park, Pang Sida National Park, Thap Lan National Park and Ta Phraya National Park. Survey locations are depicted as 3 × 3 km grids and shaded according to total survey effort (number of camera-trap nights) from 2008–2017. Forest cover adapted from Hansen et al. (Reference Hansen, Potapov, Moore, Hancher, Turubanova and Tyukavina2013).

The complex contains all major forest types characteristic of eastern Thailand, but is primarily covered by mixed evergreen and mixed dipterocarp/deciduous primary and secondary forest. It also contains grassland/scrub areas, some of which are anthropogenic. These forests have been influenced to varying degrees by a complex history of human presence and exploitation, including logging, settlements, agriculture and other activities (Lynam et al., Reference Lynam, Round and Brockelman2006). Currently, the complex is surrounded almost completely by a human-dominated matrix of villages, farmland and infrastructure.

Methods

We conducted camera-trap surveys during March 2008–February 2017. The study design was opportunistic because of limited resources, and data collection for the five protected areas varied in spatial and temporal extent (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Material 1), precluding analysis within an occupancy framework. We placed camera traps in locations suitable for tigers, to maximize detections. Such locations included geographical or topographic features (e.g. ridges, river valleys) and access roads or trails likely to be used regularly by tigers (Karanth, Reference Karanth1995; Karanth & Nichols, Reference Karanth and Nichols1998). We also used tiger track and sign (e.g. pugmarks, scats), and presence of prey species, to identify prospective camera locations.

We considered consecutive detections of a species at one camera station to be independent if they occurred after > 30 minutes (O'Brien et al., Reference O'brien, Kinnaird and Wibisono2003). Individual tigers were given an alphanumeric identifier to compile detection histories. Tigers not conclusively identified were marked as unknown. We calculated detection rates of tigers and prey as number of detections per 100 camera-trap nights, with cumulative rates reported for each protected area across survey years. Although such indices do not reliably indicate abundance (Jennelle et al., Reference Jennelle, Runge and Mackenzie2002; Sollmann et al., Reference Sollmann, Mohamed, Samejima and Wilting2013), we also carried out a comparative analysis of photographic capture rates for tigers and prey for all five protected areas (Supplementary Material 1).

Results

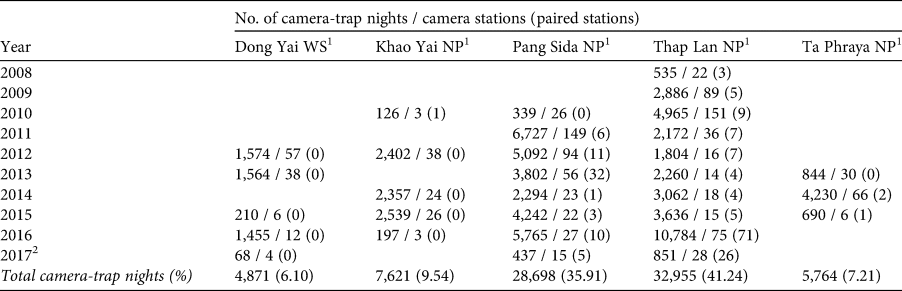

Camera traps were active for a total of 79,909 camera-trap nights at 914 locations. Survey effort varied significantly across protected areas. Thap Lan National Park (32,955 camera-trap nights) and Pang Sida National Park (28,698 camera-trap nights) accounted for c. 77.15% (61,653) of total camera-trap nights and c. 74.18% (n = 678) of stations. Survey effort by protected area and year is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 Survey effort across protected areas in Thailand's Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex during 2008–2017, showing camera-trap nights and total number of camera stations (stations with paired camera traps in brackets).

1 WS, Wildlife Sanctuary; NP, National Park.

2 January–February only.

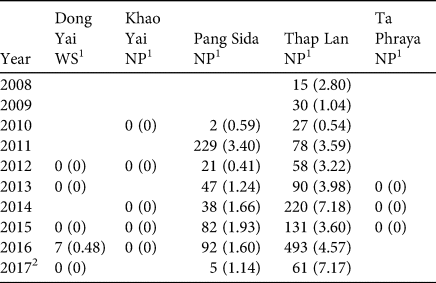

Surveys recorded 1,726 independent detections of tigers during the study period (Table 2). Tigers were documented in three of the five protected areas (Thap Lan National Park, Pang Sida National Park and Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary), with Thap Lan National Park and Pang Sida National Park accounting for > 99% of detections (1,203 and 516 detections, respectively). Tigers were detected in Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary only in 2016 (seven detections). Tigers were not detected in Khao Yai National Park and Ta Phraya National Park. Detection rates in Thap Lan National Park were higher than in Pang Sida National Park with cumulative means of 3.65 (range 0.54–7.18) and 1.80 (range 0.41–3.40) detections per 100 camera-trap nights, respectively.

Table 2 Cumulative tiger Panthera tigris detections and detection rates (detections per 100 camera-trap nights) for protected areas in the Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex during 2008–2017.

1 WS, Wildlife Sanctuary; NP, National Park.

2 January–February only.

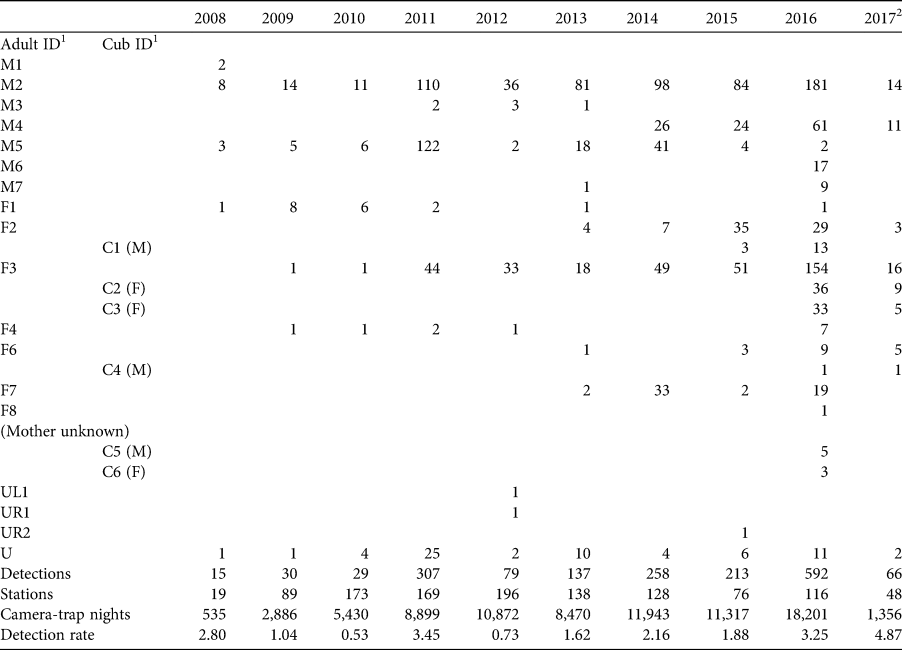

In total, at least 16 adults were documented: seven females, seven males and 2–3 partially identified adults whose sex could not be confirmed (Table 3). A minimum of 12 individuals were documented in Thap Lan National Park, nine in Pang Sida National Park and two in Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary, with six being detected across multiple protected areas. The number of individual tigers detected was highly correlated with survey effort. Five individuals were recorded over a period of ≥ 8 years, and six individuals over 3–5 years (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Material 1).

Table 3 Individual tiger detections during the study period. Cubs are placed under their mother with the exception of C5 and C6 whose mother was not confirmed. Blank cells indicate no detections.

1M indicates male and F female individuals; U is used for individuals for which only one side was photographed, with L and R denoting whether the left or right flank of the individual was captured (sex could not be determined for these individuals and it is unknown whether UL1 is the same tiger as UR1 or UR2); U without L or R denotes detections of unidentified individuals (poor image quality or partial photographs).

2January–February only.

Surveys documented successful breeding in 2015 and 2016, with six cubs/juveniles from four adult females. One litter of two juveniles were photographed without their mother (who could thus not be identified). One cub (C1), first documented in 2015, appeared to be independent from its mother by 2017.

We documented six potential prey species: gaur Bos gaurus, banteng Bos javanicus, Chinese serow Capricornis milneedwardsii, northern red muntjac Muntiacus vaginalis, sambar Rusa unicolor and wild boar Sus scrofa. We considered these species potential tiger prey based on information from Thailand and elsewhere within the tiger's range (Karanth et al., Reference Karanth, Nichols, Kumar, Link and Hines2004; Sunquist, Reference Sunquist, Tilson and Nyhus2010; Steinmetz et al., Reference Steinmetz, Seuaturien and Chutipong2013). All but one potential prey species (banteng) were documented in all five protected areas.

Mean cumulative detection rates of sambar (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Material 1) were considerably higher in Thap Lan National Park (14.70 detections per 100 camera-trap nights) than in other protected areas (0.02–8.67), whereas detection rates of other prey species were comparatively lower in this Park. Mean cumulative detection rates for wild boar were highest in Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary (6.67 detections per 100 camera-trap nights) and Pang Sida National Park (6.66). Sambar and wild boar were generally detected more frequently than other prey species.

Although tigers were the primary focus of surveys, we also documented a number of other species (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Material 1), with 947 detections of other felids, including the Asiatic golden cat Catopuma temminckii (35 detections), mainland clouded leopard Neofelis nebulosa (158), marbled cat Pardofelis marmorata (30) and leopard cat Prionailurus bengalensis (724). We did not detect leopards Panthera pardus. We documented 37 mammal species in total, including one Critically Endangered, five Endangered, 10 Vulnerable, three Near Threatened and 18 categorized as Least Concern.

Discussion

This study provides insights into tigers and their prey in the understudied Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex. Most of our detections of tigers were in Thap Lan and Pang Sida National Parks, potentially a result of larger survey effort (32,955 and 28,698 camera-trap nights, respectively, of a total of 79,909). This was the result of our opportunistic study design, which prioritized survey areas based on potential or confirmed tiger presence. Nonetheless, the absence of detections of tigers or their sign from two of the five protected areas, despite reasonable survey effort, suggests higher tiger abundance in these two Parks than elsewhere in this forest complex. Tiger presence across the complex appears to be heterogeneous, but to an unknown degree. Our records from Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary are from an area just outside the formerly known extant range of P. tigris (Goodrich et al., Reference Goodrich, Lynam, Miquelle, Wibisono, Kawanishi and Pattanavibool2015). The lack of tiger detections from Khao Yai National Park is consistent with speculation that tigers have been extirpated from this protected area (Lynam et al., Reference Lynam, Round and Brockelman2006; Jenks et al., Reference Jenks, Chanteap, Damrongchainarony, Cutter, Cutter and Redford2011), although our survey effort and coverage in this Park was relatively low (7,621 camera-trap nights).

Although the number of tigers we documented in the complex is not a population estimate, our results suggest the population may be larger than previously assumed (Lynam, Reference Lynam2010), and also document the long-term persistence of a number of individuals in this area (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Material 1). To our knowledge, the photographs of tiger cubs we obtained are the first confirmed records of successful breeding in the forest complex since at least 1999 (Lynam et al., Reference Lynam, Kanwatanakid and Suckaseam2003, Reference Lynam, Round and Brockelman2006; Jenks et al., Reference Jenks, Chanteap, Damrongchainarony, Cutter, Cutter and Redford2011) and confirm that the site supports a breeding population. Breeding and subsequent dispersal could potentially result in expansion into Khao Yai National Park, and contribute to overall population recovery.

The presence of prey is important for tiger distribution, density and persistence (Karanth & Stith, Reference Karanth, Stith, Seidensticker, Jackson and Christie1999; Karanth et al., Reference Karanth, Nichols, Kumar, Link and Hines2004), as noted by studies elsewhere in Thailand (Steinmetz et al., Reference Steinmetz, Seuaturien and Chutipong2013; Simcharoen et al., Reference Simcharoen, Savini, Gale, Simcharoen, Duangchantrasiri, Pakpien and Smith2014). Thap Lan and Pang Sida National Parks both had relatively higher rates of detection of sambar and wild boar, respectively, two species with which tigers have strong associations (Ngoprasert et al., Reference Ngoprasert, Lynam, Sukmasuang, Tantipisanuh, Chutipong and Steinmetz2012) and that are important prey elsewhere in the tiger's range (Sunquist et al., Reference Sunquist, Karanth, Sunquist, Seidensticker, Jackson and Christie1999; Biswas & Sankar, Reference Biswas and Sankar2002; Hayward et al., Reference Hayward, Jedrzejewski and Jedrzewska2012). However, a dedicated prey study is required to determine the extent to which tigers in these parks rely on these species. Low prey detection rates in Ta Phraya National Park and Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary could explain the absence of tiger detections in these two areas.

We did not detect leopards, which, given that they have similar behavioural patterns to tigers and can tolerate some degree of spatial overlap (Karanth & Sunquist, Reference Karanth and Sunquist1995; Andheria et al., Reference Andheria, Karanth and Kumar2007), suggests they may be absent from the forest complex. The Indochinese leopard Panthera pardus delacouri has not been detected recently in other parts of South-east Asia, suggesting a decline in its population and range (Rostro-García et al., Reference Rostro-García, Kamler, Ash, Clements, Gibson and Lynam2016). Abundance and diversity of suitable prey are important for the co-existence of tigers and leopards (Karanth & Sunquist, Reference Karanth and Sunquist1995; Andheria et al., Reference Andheria, Karanth and Kumar2007). Historical overhunting of prey in the forest complex could have driven competitive exclusion of leopards by tigers or other carnivores (Harihar et al., Reference Harihar, Pandav and Goyal2011; Volmer et al., Reference Volmer, Hölzchen, Wurster, Ferreras and Hertler2017). Direct hunting by humans may have also driven population declines. However, given the paucity of reliable historical data, the reasons for the absence of the leopard in the Dong Phayeyen-Khao Yai Forest Complex remain unconfirmed.

Our data could not be used to estimate tiger occupancy or population size because the study design would violate key assumptions of the appropriate methods (Harmsen et al., Reference Harmsen, Foster, Silver, Ostro and Doncaster2010; Welsh et al., Reference Welsh, Lindenmayer and Donnelly2013). Methodologically rigorous study designs should be employed wherever possible in monitoring wildlife populations, but if resources are constrained an opportunistic study design may be appropriate (Harihar et al., Reference Harihar, Prasad, Ri, Pandav, Goyal, Harihar, Kurien, Pandev and Goyal2007; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Fuller and Marker2008; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Goodrich, Hansel, Rasphone, Saypanya and Vongkhamheng2016). Although conclusions that can be drawn from such studies are limited, they can contribute important insights into species presence in poorly studied areas (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Fuller and Marker2008; Jenks et al., Reference Jenks, Chanteap, Damrongchainarony, Cutter, Cutter and Redford2011).

At the start of this study, tigers were believed to have disappeared from Khao Yai National Park (Lynam, Reference Lynam2001; Lynam et al., Reference Lynam, Round and Brockelman2006; Jenks et al., Reference Jenks, Chanteap, Damrongchainarony, Cutter, Cutter and Redford2011), information was lacking for other areas and resources were limited. In these circumstances, an opportunistic study design was suitable to address our fundamental research question, specifically, to confirm tiger presence. Early findings suggested tigers were present in the area, which enabled us to secure further funding and improved access to resources such as camera traps that were later used for tiger density and population estimates. Additional funding also enabled investments in law enforcement, patrol-based monitoring and community outreach programmes. To build on this work, we recommend additional analyses to model relationships between tigers, prey, threats and habitat required for spatial prioritization of protection and recovery interventions.

Our study provides insight into what is probably one of the most important extant tiger populations remaining in mainland South-east Asia. A comprehensive investigation of the tiger in other understudied sites in the region is urgently needed to generate a more accurate picture of their status. To recover and double the population of wild tigers (Global Tiger Initiative, 2011; Harihar et al., Reference Harihar, Chanchani, Borah, Crouthers, Darman and Gray2018), additional resources will need to be allocated to implement robust monitoring in sites where tigers remain.

To our knowledge, our work is the first to assess the tiger population across the Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex and suggests this region is important for the Indochinese tiger, which has lost most of its range in South-east Asia. Our findings establish this forest complex as home to one of the few remaining breeding populations of Indochinese tigers, demonstrate the long-term persistence of some individuals, and suggest heterogeneous tiger presence across the five protected areas, potentially influenced by distribution of prey species. Our initial results have catalysed increased research and conservation investment in this landscape at a critical time for tiger conservation in South-east Asia.

Acknowledgements

We thank Thailand's Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, Somphot Duangchantrasiri and Saksit Simcharoen for their support and guidance, and the Department's rangers for their help during surveys and their efforts to protect DPKY's wildlife. This work was supported by Freeland Foundation, Panthera, World Wildlife Fund-Thailand, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Rhinoceros and Tiger Conservation Fund, David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation, Care for the Wild International/Born Free Foundation, 21st Century Tiger, and Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium. EA and ZK were supported by grants to DWM from the Robertson Foundation. We thank Songtam Suksawang, Chumphon Sukkasem, Sittichai Banpot, Chonlathorn Chammanki, Krissada Homsud, Nuwat Leelapata, Taywin Meesap, Chatri Padungpong, Wirot Rojchanajinda, Preecha Wittayaphan, Luke Stokes, Paul Thompson, Rob Steinmetz, Abishek Harihar, Thaweesak Chomyong and the late Alan Rabinowitz for their support during the project, and two anonymous reviewers for their critiques.

Author contributions

Study design and data collection: EA, TR; support in project planning and logistics: AN, PC, BJ, SR, KS; data analysis: EA, with support of ZK, DWM; writing: EA, TR, CH, ZK, DWM.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This study abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards. All research was conducted non-invasively.