Introduction

Freshwater turtles play important roles in ecosystems through their large standing crop biomass, high secondary productivity, and contribution to energy flow within and between ecosystems (Lovich et al., Reference Lovich, Ennen, Agha and Gibbons2018). They are also an important food resource for human riverine communities (Vogt, Reference Vogt2008), but overexploitation has diminished their populations. Neotropical river turtles of the genus Podocnemis are no exception, with all species considered threatened (Turtle Taxonomy Working Group, Reference Rhodin, Iverson, Bour, Fritz, Georges, Shaffer, van Dijk, Rhodin, Iverson, Saumure, Buhlmann, Pritchard and Mittermeier2017). In particular, there is an extensive history of exploitation of the Giant South American river turtle Podocnemis expansa (Bates, Reference Bates1892; Smith, Reference Smith1974). The species occurs over a vast area in the Orinoco and Amazon Rivers across eight countries (Vogt, Reference Vogt2008). When humans settled along these rivers, turtles became a valuable source of food and income. Although Indigenous Peoples had used turtles in the Amazon as a source of protein for a long time, large-scale commercialization of turtles and their eggs began only after the arrival of Europeans (Bates, Reference Bates1892; Smith, Reference Smith1974; Vogt, Reference Vogt2008). The unsustainable harvest of eggs and meat has resulted in depleted populations across the species’ range (Bates, Reference Bates1892; Klemens & Thorbjarnarson, Reference Klemens and Thorbjarnarson1995). Podocnemis expansa is currently categorized as Lower Risk/Conservation Dependent on the IUCN Red List (Tortoise & Freshwater Specialist Group, 1996), but categorization as Critically Endangered has been recommended by the Turtle Taxonomy Working Group (Reference Rhodin, Iverson, Bour, Fritz, Georges, Shaffer, van Dijk, Rhodin, Iverson, Saumure, Buhlmann, Pritchard and Mittermeier2017).

In the regions of the upper Amazon, Solimões and Madeira Rivers in the state of Amazonas, Brazil, during 1848–1859, 48 million eggs and the fat from adult turtles were rendered for lighting the streets of Manaus and for cooking oil, much of which was sent to Europe (Bates, Reference Bates1892; Smith, Reference Smith1979). In Peru, Paul Marcoy (Reference Marcoy1873) recorded that the Indigenous People from the Ucayali River could capture up to 1,000 turtles in one night, of which c. 300 were consumed or traded with European missionaries, and the remaining turtles were killed to extract their fat and eggs. Another example comes from the Middle Orinoco River in Venezuela, where the population dropped from > 330,000 in 1800 (Humboldt, Reference Humboldt1820), to 123,622 in 1945 (Ojasti, Reference Ojasti1967) and to 700–1,300 (MINAMB, 2002) in 2010 (Mogollones et al., Reference Mogollones, Rodriguez, Hernandez and Barreto2010). Although these estimates relied on different sampling methods and are therefore not directly comparable, they indicate a significant decline in the Orinoco River population (Mogollones et al., Reference Mogollones, Rodriguez, Hernandez and Barreto2010).

Multiple attempts have been made to reduce trade of the species, but hunting pressure is still high. One conservative analysis in the Brazilian Amazon suggested that in the 1980s and 1990s, 59,149–145,019 adult P. expansa were consumed annually by low-income rural communities (Peres, Reference Peres2000). In the city of Tapauá in the state of Amazonas, Brazil, with a human population of no more than 18,000, an estimated 35 tonnes (26,000 turtles, all species) were consumed per year during 2006–2007 (Pantoja-Lima et al., Reference Pantoja-Lima, Aride, Oliveira, Félix-Silva, Pezzuti and Rebêlo2014).

Many communities, biologists and governmental organizations have implemented conservation activities for P. expansa, with the first attempts to manage and protect the species in situ starting in the 1960s. These initiatives have grown in number over the years, and at least one river turtle conservation programme can be found in every country across the species’ range. The projects’ main objective is to protect nesting beaches, with the aim of reducing egg and hatchling mortality, but few have invested in monitoring to evaluate the effectiveness of their actions. As a result, only few long-term population studies have been published for the giant river turtle (Hernández & Espin, Reference Hernandez and Espin2006; Mogollones et al., Reference Mogollones, Rodriguez, Hernandez and Barreto2010; Peñaloza et al., Reference Peñaloza, Hernández, Espín, Crowder and Barreto2013; Portelinha et al., Reference Portelinha, Malvasio, Piña and Bertoluci2014). However, the high number of existing conservation projects represents an opportunity for building collaborations, learning from successes and failures, monitoring the species across its range, understanding global trends, and raising funds to address threats. In this context, researchers and conservationists working in the Amazon gathered in 2014, for the first time, to share their approaches and discuss best practices for the species' conservation. The data shared by the group enabled the first assessment of conservation projects and the first estimation of the global number of reproductive females under protection or management. Here we present the results of this assessment and analyse the current abundance patterns of the species. We also make management recommendations regarding beach protection, population monitoring, and head-starting, the practice of rearing hatchlings in captivity during their early months to a size that makes them less vulnerable to natural predation (Moll & Moll, Reference Moll and Moll2004; Burke, Reference Burke2015).

Methods

Nesting females under protection and population trends

A group of researchers and conservation practitioners from six countries across the Orinoco and Amazon Basins gathered in Balbina, Brazil, in April 2014 to compile data and discuss the current state and future of the giant South American river turtle. We gathered information on the number and location of conservation sites and the number of nesting females at each site. We used the number of nests at each site as a proxy for the number of nesting females, as the species nests once a year (Vogt, Reference Vogt2008). Based on this information we estimated the global number of nesting females under protection or management, considering data from the most recent nesting season in each case, ranging from 2012 to 2014. Additionally, we evaluated the trends in number of reproductive females for some Brazilian rivers that are monitored by federal government and for which this information was available (Projeto Quelônios da Amazônia; IBAMA, unpubl. data). We plotted the trend in number of hatchlings in each river, using a simple moving average of orders 3–5 to separate the trend component from the irregular component. We then used linear regressions to test whether the number of hatchlings varied over time in each river, evaluating whether the slope was significantly different from zero. Based on the population data, we also developed a set of recommendations for the conservation and monitoring of the species. We evaluated three specific topics: (1) protection of adult females and nesting beaches, (2) monitoring and population studies, and (3) head-starting. For each topic we develop a set of recommended best practices based on the available evidence and the experience of researchers and practitioners.

Abundance patterns

We evaluated if the spatial pattern of current numbers of nesting females is related to human factors or natural conditions, using multiple regression analyses. Firstly, we conducted an analysis using data from seven countries across the basin, in which the number of nesting females was the response variable, and predictive variables included latitude and longitude (natural patterns), human population density and distance to the closest city by river (human factors). Human population density values for each site were extracted from the WorldPop continental dataset for America (WorldPop, 2010) and correspond to the number of persons per km2 in 2010. Distance to the closest city was estimated using path distance, with rivers designated as the only possible routes between nesting beaches and the closest city. Because data on population and municipality income were available at a higher resolution for Brazil, we conducted a second analysis for locations in Brazil only (n = 69, 81% of the nesting beaches), in which we also evaluated the GDP (gross domestic product) and total population of each municipality as predictor variables (IBGE, 2010). We expected human population size and income to be negatively and positively related to the species' abundance, respectively. We used the natural logarithm of the dependent, to correct for non-homoscedasticity.

Results

Nesting females under protection and population trends

There are at least 89 sites across the Amazon and Orinoco Basins where conservation programmes are currently implementing monitoring and conservation actions for P. expansa (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). Programmes are run by governments, national park systems, rural or Indigenous communities, and NGOs. Some of these programmes were started > 40 years ago, and most of the actions implemented by these initiatives include beach protection during the nesting season, environmental education, and head-starting of hatchlings, the latter being reported by at least 21 programmes.

Fig. 1 Sites with ongoing conservation or monitoring activities for the giant river turtle Podocnemis expansa in the Amazon and Orinoco River basin, indicating the number of reproductive females estimated for each site. The size of the dots corresponds to the number of nesting females at each site.

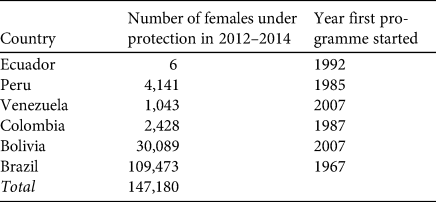

We estimated there are c. 147,000 females of P. expansa across six Amazon countries (Brazil, Colombia, Bolivia, Peru, Venezuela, and Ecuador; Fig. 1, Table 1) that are being protected, managed or monitored. Brazil has the largest number of reported nesting females (> 75% of the protected populations). Rivers such as the Guaporé and the Tapajos in Brazil are important nesting areas, with > 30,000 and > 10,000 nesting females, respectively. The population at the Iténez Reserve (Beni Department), on the Guaporé (Iténez) River in Bolivia, is the largest protected population outside Brazil (30,000 nesting females). Analysis of the trends in number of nesting females in the Brazilian rivers monitored by Projeto Quelônios da Amazônia suggest that some populations are declining, although others appear to be stable or increasing (Fig. 2). Of the nine areas monitored, populations in at least three river basins (Trombetas, Javaés and Rio Branco) appear to be decreasing, four suggest positive trends (Tapajós, Guaporé, Foz do Amazonas, Purus), and for the other two there is no evidence of a significant trend (Table 2). It is currently not possible to evaluate the overall trend across the Amazon basin because many of the programmes have not been collecting data for > 20 years, as required to reliably evaluate population trends.

Fig. 2 Population trends of P. expansa in nine rivers monitored in Brazil (presented as simple moving average of orders 3–5). Source: IBAMA, 2016.

Table 1 Number of reproductive females (estimated from number of nests) of the giant river turtle Podocnemis expansa under conservation or management in 2014 across the species’ global range.

Table 2 Linear regression results for number of P. expansa hatchlings over time in nine river basins monitored in Brazil. Results with a slope significantly different from zero are denoted with *, negative and positive coefficients indicate negative and positive trends over time, respectively.

Abundance patterns

The multiple regression model that included data from all countries showed that only latitude had a significant negative partial effect on the number of nesting females, with higher latitudes corresponding to fewer nesting females (F (4.77) = 5.73; P < 0.001; adjusted R 2 = 0.19; Table 3). None of the other variables had a significant effect on the number of females.

Table 3 Multiple regression results indicating coefficients and significance level for the influence of latitude, longitude, population density and distance to nearest city (by river) on the number of nesting females.

1 GDP, gross domestic product.

The analysis for locations within Brazil had a similar result, again only latitude had a significant, negative partial effect on the number of nesting females (F (6.62) = 6.07; P < 0.001; adjusted R 2 = 0.31). We found no correlation between the variables representing human pressure (population density, distance to human settlements, income) and turtle abundance patterns.

Discussion

Although there are many conservation projects for P. expansa across its range, not all of them have been monitoring their populations, and only a few have published population estimates (Hernández & Espin, Reference Hernandez and Espin2006; Mogollones et al., Reference Mogollones, Rodriguez, Hernandez and Barreto2010; Peñaloza et al., Reference Peñaloza, Hernández, Espín, Crowder and Barreto2013). For the few areas in Brazil that have been monitored for > 20 years, results indicate that populations in some localities appear to be recovering and exhibiting positive trends, whereas others are declining. The general trend for the species, based on cumulative reports from resource managers working across the species’ range, is believed to be a decline compared to historical abundances. However, because only a few basins have been monitored for a sufficiently long period, it is difficult to evaluate the species’ global population status and whether it is recovering as a result of conservation interventions. The database compiled here serves as a starting point for developing a regional monitoring programme. Brazil is already implementing a comprehensive national monitoring system for turtles (IBAMA, 2016), and we recommend a simpler version to be implemented internationally, recording basic information over time, including number of nesting females, reproductive output, and human consumption.

It could seem that > 147,000 nesting females of P. expansa managed across the Amazon and Orinoco Basins is a large number. However, these numbers are dwarfed by historical accounts of the number of turtles harvested. During 1848–1859, 48 million eggs were exported annually from the upper Amazon and the Madeira (Bates, Reference Bates1892). This corresponds to c. 400,000 females (Bates, Reference Bates1892), three times the current global protected population. And although the Amazon and Orinoco Basins are vast areas with expansive river systems, where enforcement and monitoring can seem unmanageable, the 89 protected sites described here harbour an important portion of the population of P. expansa. The top six sites alone (five in Brazil and one in Bolivia) account for > 100,000 nesting females. Ensuring long-term protection of the top sites in Brazil and at least the largest population in each of the other countries would secure more than two-thirds of the protected population.

Abundance patterns of the studied turtle populations did not correlate with variables representing human use, such as human population density or nesting beach distance to human settlements. Rather, there is a strong latitudinal pattern in abundance, with more females nesting per locality at lower latitudes. This pattern may be associated with the strong currents and presence of rapids in most of the tributaries that flow north to south. We did not detect an effect of human use on present abundance patterns. However, it is possible that the variables used as measures of human use do not adequately represent actual harvesting levels, or that captured individuals are transported over long distances. There are studies from the Guaporé River that demonstrate an effect of human use on abundance patterns and size distribution at a more localized scale (Conway-Gómez, Reference Conway-Gómez2007; Lipman, Reference Lipman2008). Professional poachers may not be local to the area in which they operate, and turtles are shipped to the largest cities in the Amazon (Belém and Manaus), so our approach may not be suitable to determine whether or not human use affects turtle populations at these sites at the scale of this study.

One of the most commonly used methods used to increase natural populations of P. expansa is nest relocation (Jaffé et al., Reference Jaffé, Penaloza and Barreto2008). Long-term monitoring projects have shown that when all technical guidelines are followed, there is no reduction in hatching rate, and no difference in sex ratio, growth rate, and motor skills of hatchlings between natural nests and translocated nests (Hernandez & Espin, Reference Hernandez and Espin2006; Andrade, Reference Andrade2015). On the other hand, some research indicates that clutch relocation can affect the embryos and hatchlings in several ways: increasing post-hatching mortality and the incidence of morphological abnormalities (Jaffé et al., Reference Jaffé, Penaloza and Barreto2008), shifting sex ratio of hatchlings in species with temperature-dependent sex determination (Valenzuela & Ceballos, Reference Valenzuela, Ceballos, Páez, Morales-Betancourt, Lasso, Castaño-Mora and Bock2012), and reducing physical condition of hatchlings (Remor de Souza & Vogt, Reference Remor de Souza and Vogt1994; Jaffé et al., Reference Jaffé, Penaloza and Barreto2008). Thus, we recommend nest relocation only as a management option of last resort, in cases where reproduction would otherwise be severely compromised. Such situations could include changes in flooding dynamics caused by dams, or particularly high human pressure on turtle populations.

The most commonly used form of hatchling management, head-starting, is also one of the most controversial practices in river turtle conservation. Some authors have documented negative effects of keeping hatchlings in captivity: nutritional deficits (Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Derrickson, Beissinger, Wiley, Smith, Toone and Miller1996; Seigel & Dodd, Reference Seigel, Dodd and Klemens2000; Boede & Hernández, Reference Boede and Hernández2004) and increased probability of illnesses caused by viruses, bacteria and parasites (Seigel & Dodd, Reference Seigel, Dodd and Klemens2000; Boede & Hernández, Reference Boede and Hernández2004). Additionally, head-starting may interrupt a vital part of the turtles’ life cycle, as post-hatching parental care has been reported for this species (Ferrara et al., Reference Ferrara, Vogt and Sousa-Lima2013). Studies using population models and elasticity analyses show that the survival of river turtle populations is affected more by the survival rates of adults and subadults than that of hatchlings and yearlings (Mogollones et al., Reference Mogollones, Rodriguez, Hernandez and Barreto2010; Páez et al., Reference Páez, Bock, Espinal-García, Rendón-Valencia, Alzate-Estrada, Cartagena-Otálvaro and Heppell2015). Therefore, and considering the potential negative effects of head-starting, we recommend that turtle conservation programmes focus on in situ conservation strategies such as protecting nesting beaches and reducing the hunting of adult female turtles.

Although there are many initiatives for the conservation of P. expansa, few outside Brazil are monitoring populations to assess the effectiveness of their actions. It is possible that continued harvest for illegal trade and habitat destruction are surpassing the effects of conservation efforts (Klemens, Reference Klemens2000), as in some sites the loss of adults has exceeded recruitment. The Reserva Biológica do Rio Trombetas, which once harboured one of the largest populations of P. expansa in Brazil, had c. 6,500 nesting females in the 1960s and 1970s (Zwink & Young, Reference Zwink and Young1990). The population now consists of < 600 females (Fig. 2). Knowledge of demographic variables and parameters such as population size and structure, and age-specific survivorship, is essential for evaluating trends and determining a species’ conservation status. Monitoring and research that collects these data should thus be prioritized by organizations that lead turtle conservation programmes. In cases where it is not possible to capture turtles (because of local beliefs or restrictions) or when recapture probability is very low, at least the total number of nests and their survival probabilities should be assessed. This includes monitoring the same beaches during the entire reproductive season every year, to document potential changes in the reproductive population.

Current conservation actions may not be sufficient to prevent population declines going forward. In Brazil, the government plans to build an additional 277 hydroelectric dams in the Amazon Basin (Castello et al., Reference Castello, McGrath, Hess, Coe, Lefebvre and Petry2013). These could be a significant threat for P. expansa and other river turtles, flooding their nesting sites and feeding grounds, or isolating them from nesting beaches (Pezzuti et al., Reference Pezzuti, Vidal, Felix-Silva, Alarcon, Millican and Torres2016). Knowledge of how populations of P. expansa are currently being affected by human activities and how they are responding to conservation measures is still limited. Only through long-term monitoring of populations across the species’ range will it be possible to predict future persistence of the species and inform broad-scale conservation action. Podocnemis expansa has a large home range and migrates over hundreds of kilometres (Pezzuti et al., Reference Pezzuti, Teixeira, Silva, Lima, Kemenes, Garcia and Andrade2008; Andrade, Reference Andrade2015), which necessitates conservation actions at a broad geographical scale. A collaborative effort across nations to develop protected areas and monitor the species across both the Amazon and Orinoco Basins is essential for the survival of this species.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Eletrobrás and ICMBio, and Stella Maris Lazarine, José Ribamar da Silva Pinto, Gilmar Klein and Carlos César Durigan for their suggestions and help with the logistics of the workshop. The workshop was funded by the Turtle Conservation Fund, The Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, Wildlife Conservation Society, Turtle Survival Alliance, IUCN/SpSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, and the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Brazil.

Author contributions

Study design: GFM, CRF, RCV, RAMB, PCMA, RL, RB; fieldwork and data collection: all authors; statistical analyses, mapping, figures and tables: GFM, CRF, CKF; writing and revisions: all authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This work complies with the Oryx ethical guidelines and did not involve research on human subjects or experimentation with animals.