Introduction

The sea otter Enhydra lutris formerly occurred across the North Pacific rim, but extensive harvesting for its fur in the 18th and 19th centuries almost exterminated the species, which was saved by the International Fur Seal Treaty of 1911 (Doroff & Burdin, Reference Doroff and Burdin2015). From < 2,000 individuals in 13 colonies, the species increased in numbers and range (Kenyon, Reference Kenyon1969), but is nevertheless categorized as Endangered on the IUCN Red List (Doroff & Burdin, Reference Doroff and Burdin2015). The current range of sea otters is from northern Hokkaido, through the Kuril Islands, Commander Islands, Aleutian Islands, and the coast of North America, to California. The populations in the eastern range and on the Commander Islands have been regularly monitored (Nikulin et al., Reference Nikulin, Vertyankin, Fomin and Diyakov2008; Mamaev, Reference Mamaev, Shpak, Filatova, Glazov, Burkanov, Belikov and Kryukova2018; Shelton et al., Reference Shelton, Harvey, Samhouri, Andrews, Feist and Frick2018), but those in the south-west of the range are poorly studied. There are reports the sea otter is declining on the Kamchatka Peninsula and Kuril Islands in Russia (Doroff & Burdin, Reference Doroff and Burdin2015). Here we examine the species on Urup Island, one of the main wildlife refuges in the southern Kuril Islands. Our findings provide a basis for assessing the status of sea otter populations on the south-western extreme of their range, and illustrate the threats affecting the species.

Study area

The 116 km long Urup Island (Fig. 1) comprises mountainous and rocky terrain, and is unsuitable for large or permanent human settlements. The human population on Urup has historically been small. Land animals are few, and there are no large predators (Voronov, Reference Voronov1974). In 1958, the island was declared a reserve of regional importance by the local administration (Sakhalinskaya oblast). Unlike designation as a reserve of national importance, this status did not lead to the organization of a special institution that would deal with the protection and management of the island. However, the island is a refuge as a result of being rarely visited, and in 2003 this was underscored by the fact that the protective status was judged unnecessary, and removed (OOPT Rossii, 2021). There are two lighthouses on the island, on the extreme southern and northern tips, where a few people reside. Recently, mining for gold has begun at the southern end of the island, and a small temporary camp has been built. However, most of the island remains undeveloped, and because the harvesting of sea otters there ended in the early 20th century, we expected the species to be numerous.

Fig. 1 Urup Island, in the Kuril Islands, with the areas of the coastline where we surveyed for the sea otter Enhydra lutris in 2019.

Methods

We gathered records on the sea otters of Urup Island by examining the Russian Citation Index (2021) and Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, USA) databases, and by searching in the libraries of the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St Petersburg State University, and the Russian Institute of Game Management and Fur Farming.

We analysed the suitability of the coastal waters of the island for sea otters by using maps and aerial photographs, considering a seabed depth of 50 m as the boundary of any otter habitat. Although sea otters can dive deeper than this, their principal habitats are in waters of < 30 m depth (Bodkin et al., Reference Bodkin, Esslinger and Monson2004). We considered the sea otter habitat of Urup Island to be either optimal or suboptimal. In optimal habitats, the seabed depth reaches 50 m at a distance of at least 1 km from the coastline. Suboptimal habitats are those with a sharp increase in depth near the shore, and depths of ≤ 50 m occupying a strip of < 1 km. The coastline is irregular and we examined it in 1 km sections for this analysis.

In the summer of 2019, we surveyed sections of the island by travelling along the coastline on foot, for 15 km along the northern part of the island, and 25 km along the southern part. Each section was surveyed only once. The water surface was observed using binoculars, and the points of sea otter occurrences were recorded with a GPS, and photographed. We calculated the number of sea otters observed per km of coastline, and extrapolated abundance based on measurements of the coastline of the entire island. We moved from the northern to the southern sections of the island by boat. During this travel we searched for marine mammals but, as the vessel's route was not specifically adjusted for studying sea otters, observations from the vessel provided additional data for discussion but were not used in the calculations.

Results

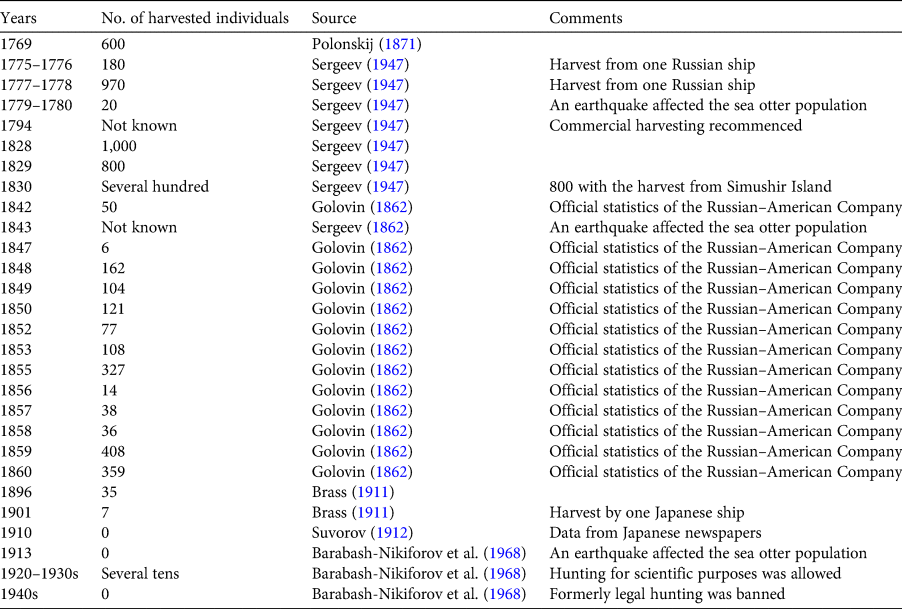

The earliest historical information about sea otters on Urup dates from the 18th century, at which time they were already the subject of hunting trade between native people and the Japanese Empire (Taniguchi, Reference Taniguchi2019). At the end of the 18th century and in the first half of 19th century the hunting of sea otters expanded, and their numbers decreased (Table 1). In addition to killing by hunters, the negative effects of earthquakes and attendant tsunamis on the number of sea otters was also noted. In the 1850s, when Urup Island belonged to the Russian Empire, restrictions were placed on the sea otter harvest. In 1875, Urup Island was ceded to Japan. During the following 5 years, the sea otters on the island were almost exterminated, and commercial hunting ended (Nikolaev, Reference Nikolaev and Arseniev1969). Hunting by the native population of the Kuril Islands (the Ainu) also stopped, when the Japanese authorities evicted them, relocating them to a village on Shikotan Island, and prohibited them from hunting (Snow, Reference Snow1897). Following this, the number of sea otters increased slightly but in the early 20th century, hunting by the Japanese resumed (Shin, Reference Shin2014). By 1912 only c. 200 sea otters remained in the Kuril Islands. As a result of protective measures consequently adopted by the Japanese government, the number of sea otters increased to 800 individuals by 1939 (Nikolaev, Reference Nikolaev and Arseniev1969), but hunting for scientific purposes continued despite the small population (Barabash-Nikiforov et al., Reference Barabash-Nikiforov, Marakov and ikolaev1968). In 1945, the island became a Russian territory again, and regulated hunting of sea otters ceased. At that time, only a few individual otters, or the complete lack thereof, were reported on Urup Island (Uspenskij, Reference Uspenskij1955; Nikolaev, Reference Nikolaev and Arseniev1969).

Table 1 Records of the harvest of sea otters Enhydra lutris on Urup Island from 1769 to the 1940s.

An increase in the number of sea otters on Urup Island was reported in 1952 (Nikolaev, Reference Nikolaev and Arseniev1969); since then there have been various surveys and estimates of the status of the population (Table 2). The methods used have not been consistent (in some cases they were not described) and therefore it is difficult to analyse changes in the population. Nevertheless, these data facilitate estimates of the scale of abundance (Table 2) and the pattern of distribution of the sea otters around the island. Several researchers examined the entire coastline, or a significant portion (Nikolaev, Reference Nikolaev1958; Kornev, Reference Kornev, Bugaev, Maximenkov, Tokranov and Cherniagina2016). They showed that sea otters occurred around the entire island, with few differences between the western and eastern coasts, but that sea otters did not occur uniformly throughout the island's coastal waters: some otter groups contained a few dozen individuals, and sea otters were not recorded in some areas.

Table 2 Number of sea otters recorded on Urup Island from 1953 to 2017, with source and information on methods employed.

The total length of the island's coastline is 287 km. Most of its coastal waters are optimal for sea otters, except for a 13 km section on the western coast (Fig. 1), where the depth increases steeply to 20 m, at a distance of 200–300 m from shore reaches 50 m, and thereafter increases steeply to 1,000 m. Hence the total length of the coastline that sea otters could potentially inhabit is 274 km.

We recorded 53 sea otters: 49 in the southern and four in the northern part of the island. Frequency of occurrence was 0–17 individuals per km, with a mean of 1.325 ± SE 0.461 per km. A naïve extrapolation to the 274 km of suitable coastline suggests a potential total of 363 ± SE 126 individuals. This is considerably lower than the population estimates from the recent past (Table 2).

We found one skeleton and one carcass of a recently-killed sea otter (i.e. it was not yet in a state of decay). The carcass had been decapitated and skinned. The skeleton did not have a skull (Plate 1). We did not see any sea otters from the boat, suggesting low abundance. The vessel's route passed near the length of coast that we identified as sub-optimal for sea otters, and we observed a family of killer whales Orcinus orca (3–5 individuals), a potential sea otter predator, there (Estes et al., Reference Estes, Tinker, Doroff and Burn2005). We did not observe killer whales in other locations along the coast.

Plate 1 The remains of sea otters Enhydra lutris on the shore of Urup Island (Fig. 1), in 2019.

Discussion

The dynamics of the sea otter population of Urup Island is an illustration of the species’ ability to increase rapidly in numbers under favourable conditions, and also that declines can occur rapidly (Bodkin, Reference Bodkin, Larson, J.L. and van Blaricom2015). Currently, the number of sea otters on the island appears to be low compared with historical numbers. A low number could partly be explained by migration and redistribution. However, it is unlikely that numbers would drop frequently for this reason alone, because the habitats of neighbouring islands are less suitable for sea otters. The islands to the north are smaller, and sea otters have historically been less abundant there (Snow, Reference Snow1897). South of Urup lies the larger Iturup Island, with a relatively large human population and economic activity, it is less suitable for sea otters than Urup.

Several processes causing the decline of sea otter populations have been reported. It is believed that the decline in the Commander Islands occurred as a result of a lack of food (sea urchins, benthic crustaceans and molluscs) preceded by a sharp increase in the number of sea otters; i.e. fluctuations in numbers of sea otters as a result of predator–prey relationships (Mamaev, Reference Mamaev, Shpak, Filatova, Glazov, Burkanov, Belikov and Kryukova2018). In the case of Urup, this is unlikely to have resulted in the low numbers of sea otters we observed because the small population is unlikely to have overexploited the available food resources. Decreasing numbers of sea otters in the Aleutian Islands were associated with predation by killer whales (Doroff et al., Reference Doroff, Estes, Tinker, Burn and Evans2003). A similar situation has been reported in California, where predation by great white sharks Carcharodon carcharias has become more frequent (Tinker et al., Reference Tinker, Hatfield, Harris and Ames2016). Changes in predator behaviour that affect sea otters are associated with global declines of fish and other targets of human consumption (Ellis, Reference Ellis2004). Carcasses of sea otters displaying signs of predation have not, however, been observed on Urup Island.

In California, parasites also caused increased sea otter mortality (Thomas & Cole, Reference Thomas and Cole1996; Conrad et al., Reference Conrad, Miller, Kreuder, James, Mazet and Dabritz2005; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Tinker, Estes, Conrad, Staedler and Miller2009). At least some (Sarcocystis neurona, Toxoplasma gondii) were transmitted from land mammals: opossums Didelphis virginiana and felids. However, such mammals do not occur in Urup Island, although there are foxes Vulpes vulpes, American mink Neovison vison and rats Rattus norvegicus (Kostenko et al., Reference Kostenko, Nesterenko and Truhin2004). We did not locate any sea otter carcasses on the shore that suggested death from disease. Attacks on sea otters by feral dogs have been reported on Urup Island (Voronov, Reference Voronov1964), but feral dogs have not been reported since at least the 1990s (Kostenko et al., Reference Kostenko, Nesterenko and Truhin2004). Other potential threats to sea otters include oil spills, other environmental contaminants, entanglement in fishing gear, vessel strikes, human disturbance, and poaching (Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 2014; Doroff & Burdin, Reference Doroff and Burdin2015; Mamaev, Reference Mamaev, Shpak, Filatova, Glazov, Burkanov, Belikov and Kryukova2018). As Urup Island is largely uninhabited, most of these factors are probably insignificant, but the two dismembered, skinned carcasses that we found on the shore suggest poaching.

Poaching is likely to be stimulated by illegal trade in otter fur. In 2005, selling of sea otter skins was reported in Moscow and Kamchatka, most of which later appeared in Chinese markets (Doroff & Burdin, Reference Doroff and Burdin2015). In this case the sea otters were illegally hunted in the reserve on the Commander Islands. The same is now probably occurring in the southern Kuril Islands. The demand from China appears to be a potential driver of the poaching of sea otters because, unlike in other countries where fur is in use, in China otter fur is of particular value, prized not only for its decorative beauty but also for cultural superstitions and traditional medicine. It was believed that this tradition ended when the Dalai Lama criticized the use of wild animal fur in 2006 (Yongdan, Reference Yongdan2018), but this action may have only had a temporary and insubstantial effect, as the trade of otter skins has continued (International Otter Survival Fund, 2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank Alexey Diukov for help with English, and the Russian Geographical Society and the Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation for the organization of the expedition to the Kuril Islands.

Author contributions

Both authors contributed equally to study design, fieldwork, data analysis and writing.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.