The giant otter Pteronura brasiliensis, categorized as Endangered on the IUCN Red List (Groenendijk et al., Reference Groenendijk, Duplaix, Marmontel, van Damme and Schenck2015), was once widely distributed throughout South America from northern Argentina to Colombia and Venezuela (Carter & Rosas, Reference Carter and Rosas1997). However, because of the commercial value of its fur, overhunting in the 1950s and 1960s led to the collapse of its populations and extinction over a large part of its original range (Carter & Rosas, Reference Carter and Rosas1997). In the 1960s in Llanos Orientales de Colombia (Orinoco Basin) the species was present only in the remote upper reaches of the rivers (Medem, Reference Medem1968). More recent studies have shown that the species is now present throughout the area (Carrasquilla, Reference Carrasquilla2002; Díaz, Reference Díaz2007). However, the methods used in these studies did not provide information that permits an evaluation of the species' conservation status. Our objective therefore was to estimate the abundance and density of the giant otter population along the Orinoco river, and its tributaries and lagoons, in the municipality of Puerto Carreño, in Vichada, Colombia.

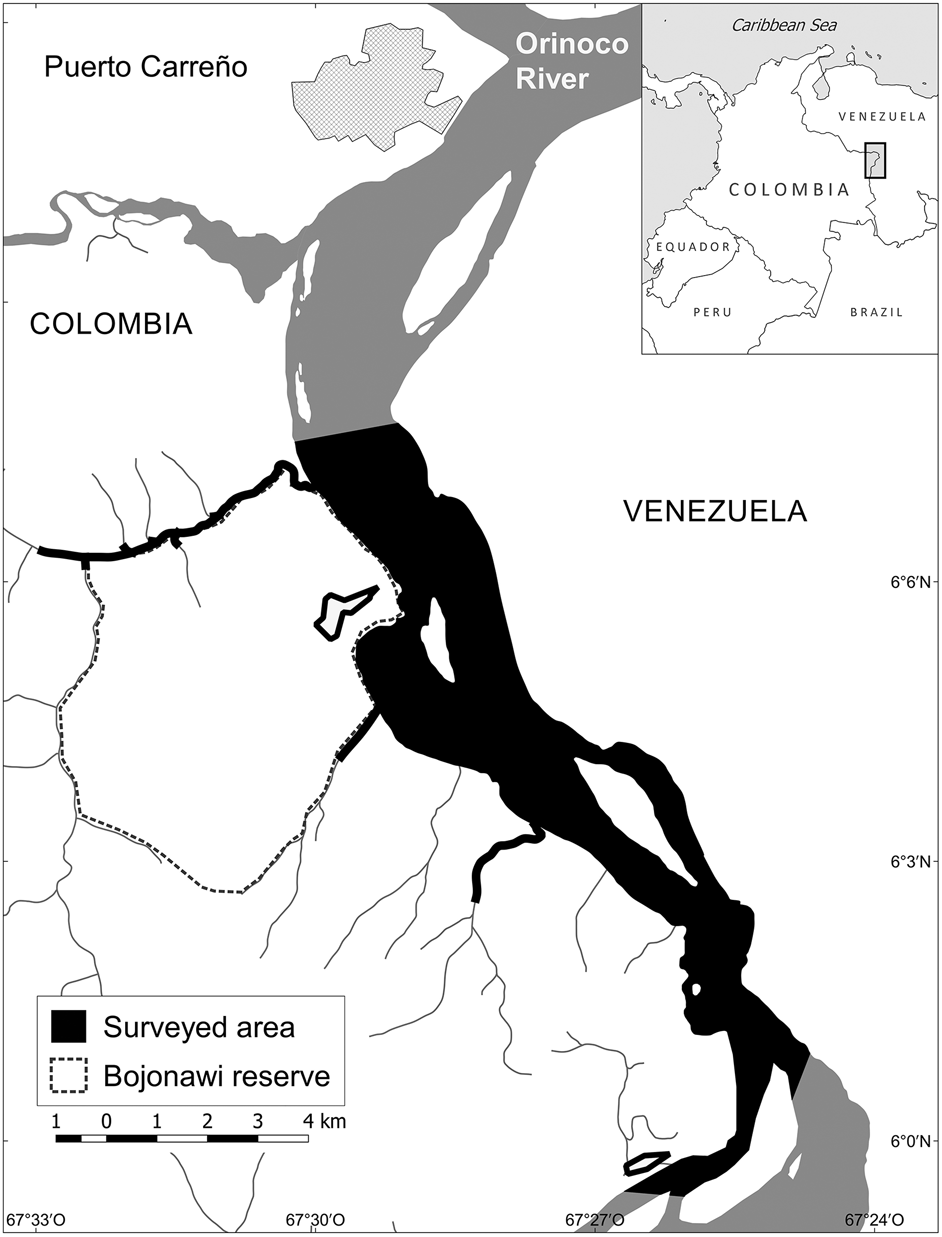

This study was carried out along the Orinoco river in the municipality of Puerto Carreño in the north-east of the Department of Vichada (Fig. 1). This department lies at altitudes of 50–100 m, has a mean annual temperature of 28 °C, and the mean total annual precipitation is 2,176 mm, with dry (December–March) and rainy (April–November) seasons (IGAC, 1996). The study area includes the Bojonawi private nature reserve, and lies in the El Tuparro Biosphere Reserve. Important commercial and recreational fishing activities occur in this area.

Fig. 1 The study area in eastern Colombia, showing river sections and lagoons surveyed.

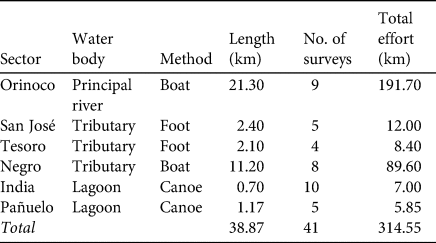

Giant otters are territorial, diurnal, live in groups and have irregular pale patterning on their throats that allows individuals to be identified (Duplaix, Reference Duplaix1980), facilitating estimation of population size by direct counts of groups and individuals (Groenendijk et al., Reference Groenendijk, Hajek, Duplaix, Reuther, van Damme and Schenck2005). Given the logistical impossibility of sampling continuously, the area was divided into six sectors, which were sampled independently (Table 1). Depending on accessibility, each sector was sampled using either a 9-m motorized aluminium boat with a 25-hp engine or a canoe, or on foot along the banks of streams where access by boat was impossible. Surveys were conducted by three experienced observers during 7.30–18.00. When we detected an individual or group of otters, we followed them until the pale throat patterns of each individual could be photographed and the size of the group established. We recorded group sizes and locations using a GPS, which we also used to calculate the length of each transect. The surveys were carried out during 15 January–9 March 2018 during the dry season, when the otters are easiest to detect (Groenendijk et al., Reference Groenendijk, Hajek, Duplaix, Reuther, van Damme and Schenck2005).

Table 1 The six sectors surveyed for the giant river otter Pteronura brasiliensis in Colombia (Fig. 1), with type of water body, survey method, length of each sector, number of surveys of each sector, and total survey effort.

The study area comprised a total of 38.87 linear km, including the main river, its tributaries and lagoons. Each sector was sampled repeatedly, giving a total survey effort of 314.55 linear km (Table 1). Six groups of giant otters and two solitary individuals were detected. The groups consisted of 2–11 individuals, with a mean of 4.67 ± SD 3.39 individuals per group. In total, 30 otters were identified, yielding a minimum density of 0.77 individuals per km.

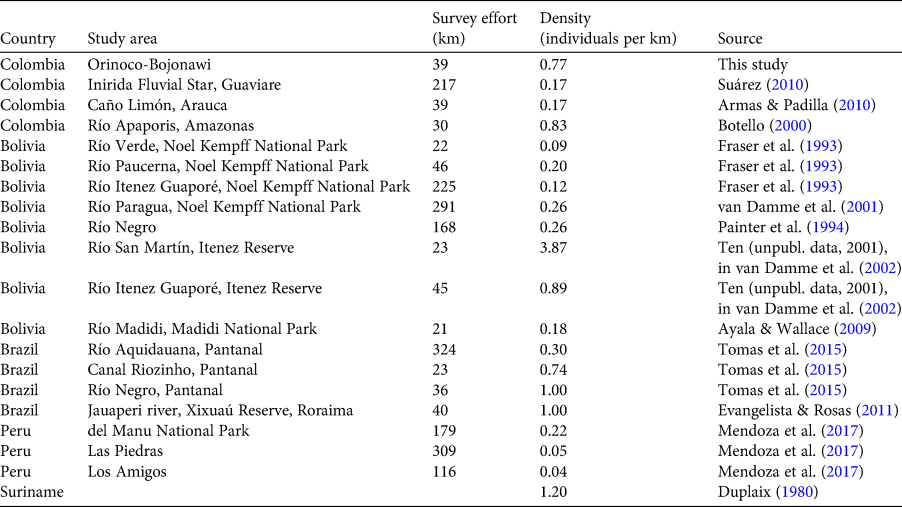

Our results show that the giant otter density along the river Orinoco and its tributaries and lagoons in the Puerto Carreño area is among the highest reported for the species in Colombia (Table 2), similar to the 0.8 individuals per km in the Apaporis river in the Amazon Basin (Botello, Reference Botello2000) and greater than the 0.17 individuals per km in the Inirida Fluvial Star and the tributaries of the upper Orinoco river (Suarez, Reference Suárez2010). Compared to elsewhere in South America, the density we recorded is similar to the highest densities reported for the species in the Brazilian Pantanal (0.74–1.00 individuals per km; Tomas et al., Reference Tomas, Camilo, Ribas, Leuchtenberger, Borges, Mourão and Pellegrin2015) but lower than in the river San Martín in Bolivia (3.87 individuals per km; van Damme et al., Reference van Damme, Ten, Wallace, Painter, Taber and Gonzales Jimenes2002) and Suriname (1.2 individuals per km; Duplaix, Reference Duplaix1980). However, the latter two areas are remote, with few people. Otters occur in lower densities in areas where they are killed by fishers, or prey is scarce because of poor river productivity or overfishing (Trujillo et al., Reference Trujillo, Caro, Martínez and Rodríguez-Maldonado2015).

Table 2 Compilation of studies of the giant otter, with length of water body surveyed (effort) and density of individuals observed.

The Orinoco is a highly productive river with high fish densities (Lasso et al., Reference Lasso, Usma, Trujillo and Rial2010) and consequently supports healthy giant otter populations. Nevertheless, this abundance of fish in an accessible area close to a population centre also encourages fishing. During our study, we identified at least eight fishers’ camps on the rivers Orinoco and Caño Negro, and the city of Puerto Carreño is host to c. 1,000 recreational fishers every fishing season (December–March). Given that killing by fishers is one of the main threats to this otter throughout much of its range (Rosas, Reference Rosas and Cintra2004; Recharte et al., Reference Recharte, Bowler and Bodmer2009; Trujillo et al., Reference Trujillo, Caro, Martínez and Rodríguez-Maldonado2015), we would expect this to occur in a popular fishing area. However, a study carried out amongst fishers in Puerto Carreño in 2018 indicated that 93% believed that otters were not harmful to fishing activity (Garrote, Reference Garrote2019).

Nevertheless, there is pressure on fish stocks: both the number of fish caught and their mean size have fallen significantly since 2000 (Trujillo et al., Reference Trujillo, Caro, Martínez and Rodríguez-Maldonado2015). This could potentially lead to a decrease in the carrying capacity for the giant otter, and to increased competition between otters and fishers, jeopardizing the positive perception that fishers have of this species (Lavigne, Reference Lavigne1997). Further threats to the species in the Puerto Carreño area include the illegal trade of skins and the capture of cubs as pets (Cruz Antía et al., Reference Cruz-Antia and Gómez2010; Trujillo et al., Reference Trujillo, Caro, Martínez and Rodríguez-Maldonado2015).

Given the high density of the giant otter in this well-developed area, our results highlight the importance of this population for the conservation of the species. We will continue to monitor this population, seeking to improve our understanding of the dynamics driving the relative high density and the fishers' favourable perception of the species.

Acknowledgements

This study was carried out within the framework of the project ‘Population monitoring and strategies for the conservation of the giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) in the Bojonawi Reserve’, funded by the Fundación Barcelona Zoo and Ayuntamiento de Barcelona.

Author contributions

Study conception and design: GG, FT; data collection and analysis: GG, BC, JME, LP, JT, BM; writing: all authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.