Introduction

The Indian pangolin Manis crassicaudata is categorized as Endangered on the IUCN Red List (Baillie et al., Reference Baillie, Challender, Kaspal, Khatiwada, Mohapatra and Nash2014) because of its declining populations, which is a result of illegal hunting and increased levels of poaching for its scales and meat (Baillie et al., Reference Baillie, Challender, Kaspal, Khatiwada, Mohapatra and Nash2014). It is one of four Asian pangolin species, all of which have protective keratinized scales (Gaudin et al., Reference Gaudin, Emry and Pogue2006; Gaubert, Reference Gaubert, Wilson and Mittermeier2011). The scales are used in traditional medicine in China and other countries, and Indian pangolins are traded illegally throughout East Asia (Challender et al., Reference Challender, Harrop and MacMillan2015), with many reports of seizures in Vietnam in recent years (EIA, 2015).

All eight species of pangolins (four Asian and four African) are on Appendix I of CITES (2017), and pangolins are considered to be the most trafficked wild mammal globally (Challender et al., Reference Challender, Harrop and MacMillan2015), with an estimated > 277,000 individuals of both Asian and African origin traded since 2000. This trade is recognized as having a severe impact on the status of pangolin populations (Challender et al., Reference Challender, Harrop and MacMillan2015).

The Indian pangolin occurs in five countries: Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka (Baillie et al., Reference Baillie, Challender, Kaspal, Khatiwada, Mohapatra and Nash2014). In Pakistan the distribution is localized, with the species occurring in the provinces of Sind, Balochistan, some parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhawa and Punjab, including the Potohar Plateau (Roberts, Reference Roberts1997).

The Indian pangolin occurs in barren hilly areas and subtropical thorn forests (Roberts, Reference Roberts1997), usually ranging from moist to dry and thorn to grassland (Pai, Reference Pai2008). It occurs at naturally low population densities and prefers forested environments of various types (Gaudin et al., Reference Gaudin, Emry and Pogue2006). It is also found in ruined wasteland near human settlements (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Chen, Chang, Lin, Block, Lorentsen and Dierenfeld2007). The pangolin's scales provide defence against predators; when threatened, it rolls up into a ball to protect its delicate, vulnerable underside. Demand for the scales for use in traditional medicine has fuelled intensive poaching of the species, resulting in a decline of c. 79% in its native range (Irshad et al., Reference Irshad, Mahmood, Hussain and Nadeem2015).

The Potohar Plateau is the core distribution range of the Indian pangolin in Pakistan, with only localized, patchy distributions in other areas. Previous studies (e.g. Mahmood et al., Reference Mahmood, Hussain, Irshad, Akrim and Nadeem2012) have highlighted the illegal trade and killing of Indian pangolins in Pakistan and the smuggling of their scales into China via Hong Kong (and perhaps Singapore). In April 2012 information was reported (GACC, 2012) on a seizure in China of 25.4 kg of pangolin scales that were apparently sourced from Pakistan, where illegal smuggling is facilitated by weak law enforcement.

We aimed to estimate the distribution range of the Indian pangolin on the Potohar Plateau, where a high intensity of illegal killing has been reported, and compare it with the IUCN estimate, to assess the intensity of illegal hunting pressure on the species on the Plateau, and to evaluate the efficacy of the protection system in place.

Study area

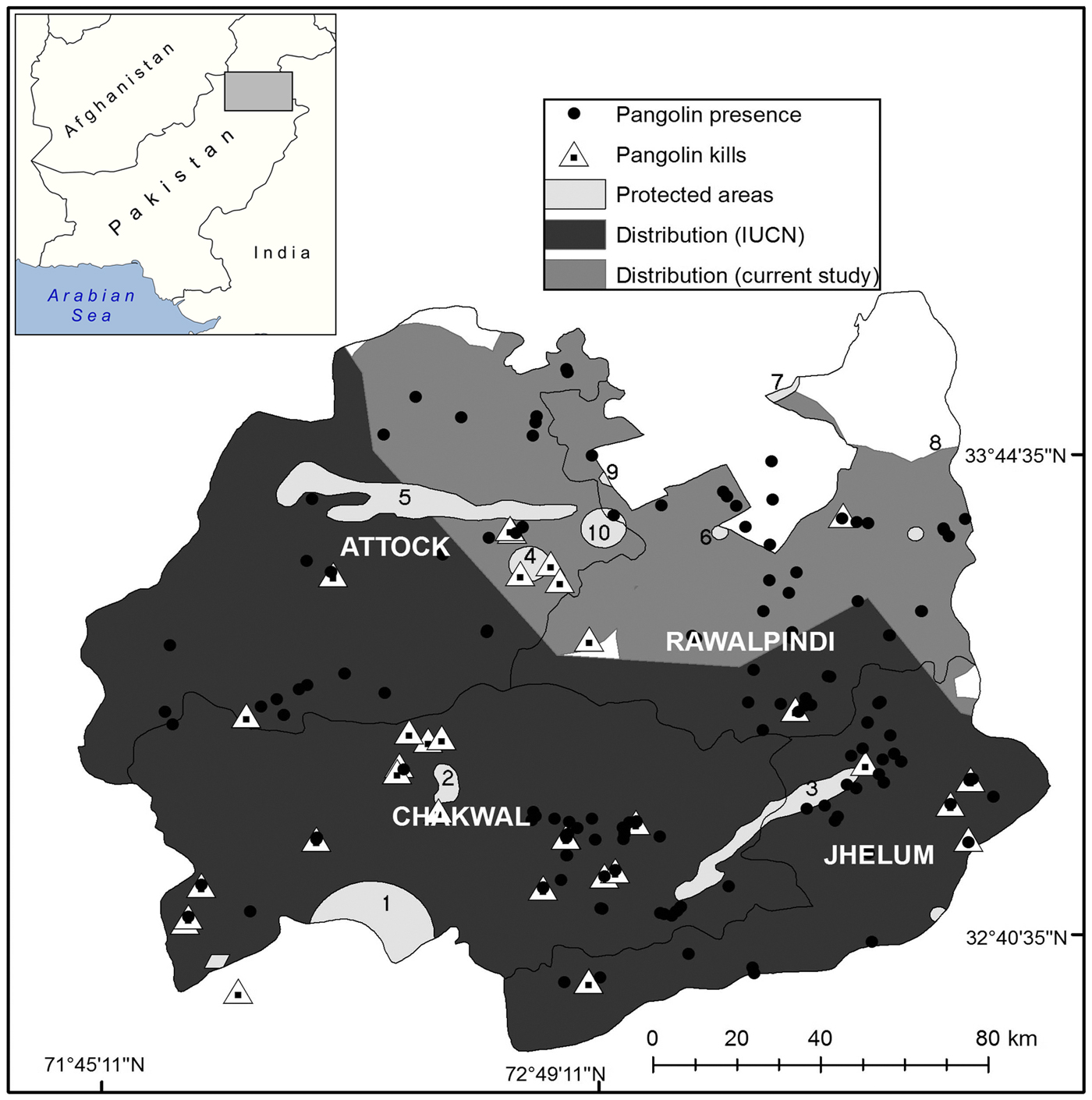

The study was conducted on the Potohar Plateau in north-east Pakistan (Fig. 1) during 2011–2013. The 22,255 km2 study area comprises four districts (Attock, 6,857 km2; Chakwal, 6,525 km2; Jhelum, 3,587 km2; Rawalpindi, 5,286 km2), and also some parts of the capital city, Islamabad (Bhutta, Reference Bhutta1999). The Plateau is at 330–1,000 m altitude and the climate is semi-arid to humid, with mean annual rainfall of 380–510 mm. The mean maximum temperature in summer is 45°C, dropping to below freezing during winter (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2010). Of the 178 protected areas in Pakistan 10 occur on the Potohar Plateau: six National Parks (Kala Chitta, Chinji, Ayub, Margalla Hills, Murree-Kahuta-Kotli Sattiyan and Ayubia), two Wildlife Sanctuaries (Chumbi Surla and Islamabad) and two Game Reserves (Domeli-Diljaba and Khairi Murat; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 The distribution of the Indian pangolin Manis crassicaudata on the Potohar Plateau estimated by this study and indicated by the IUCN assessment for the species (Baillie et al., Reference Baillie, Challender, Kaspal, Khatiwada, Mohapatra and Nash2014), with locations where pangolins were recorded, and locations where illegal capture and killing of pangolins was recorded. Protected areas are numbered as in Table 2.

Fig. 2 Numbers of Indian pangolins killed illegally on Potohar Plateau, Pakistan (Fig. 1) during January 2011–April 2013.

Methods

Preliminary species occurrence data were obtained by interviewing local people using a questionnaire (Supplementary Material 1). Field data were collected during surveys of all natural areas of the four districts (Jhelum, Chakwal, Rawalpindi and Attock) of the Plateau. The interviews and field surveys were conducted between January 2011 and the end of April 2013. The field surveys were conducted using a motor vehicle driven at 25–30 km per hour along all accessible roads, guided by the published occurrence records of the species. Direct (sightings, capture, dead bodies) and indirect (burrows, faeces) signs of the species were recorded at stops every 5–7 km. Thorough searches were carried out at sites where the species was reported to occur. Geographical coordinates of the locations of occurrence were recorded using a global positioning system, and were used to construct distribution maps of the species and estimate its distribution range in the study area.

The occurrence data were georeferenced and uploaded to GoogleEarth (Google Inc., Mountain View, USA) and saved in Keyhole Markup Language format before being imported into QGIS v. 1.8.0 (QGIS Development Team, 2012) and converted into shapefiles. The result was a layer of location points where the species was known to be present. For each location point we created a buffer of 5 km2, which approximates our estimate of the home range size of the Indian pangolin in Pakistan based on its daily activity. There are no published records of the home range size of the Indian pangolin, although the home range of the Sunda pangolin Manis javanica in Singapore was estimated to be considerably smaller (c. 0.7 km2 for females, and larger for males; Lim & Ng, Reference Lim and Ng2008).

We then clipped areas outside the study area, using a shapefile of the Plateau obtained from the global topographical data layer from WebGIS (2012). We created a polygon incorporating all the buffers to construct the distribution range of the Indian pangolin in the study area. The distribution of the Indian pangolin provided by IUCN was retrieved as a shapefile from the Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN, 2014). To examine the occurrence of the Indian pangolin with respect to protected areas, we compared the species’ distribution to the locations of the protected areas on the Potohar Plateau, obtained from the World Database on Protected Areas (IUCN, UNEP-WCMC, 2014).

Questionnaire surveys (Supplementary Material 1) were conducted with local people in the study area (including hunters, shepherds, shop keepers and school children) to gather data about illegal capture and killing of Indian pangolins. During the survey period a total of 36 monthly field visits were conducted. Based on information obtained from the questionnaires we recovered a number of dead pangolins (without scales), and scale jackets (which remain after a pangolin has died and decayed). Local people do not use scale jackets for decorative purposes but sell them in local markets.

Results

Spatial distribution

We recorded 158 locations across the four Districts of the Potohar Plateau (Attock, 34; Chakwal, 44; Jhelum, 35; Rawalpindi, 45) where there were direct sightings or indirect signs of Indian pangolins (Fig. 1). Based on these occurrences we determined that the species occurs in c. 89% (19,854 km2) of the Plateau rather than in the c. 71% (15,801 km2) indicated in the IUCN Red List account for the species (Baillie et al., Reference Baillie, Challender, Kaspal, Khatiwada, Mohapatra and Nash2014; Fig. 1). At least 40 locations (in Rawalpindi and Attock Districts) were outside the range indicated by IUCN. The elevational range of the Indian pangolin on the Plateau was 202–879 m; in Rawalpindi District the species occurred from 457 (Gujar Khan) to 593 m (Kahuta), in Chakwal District from 478 (Mureed) to 879 m (Basharat Hills), in Jhelum District from 202 (Haranpur Victoria pul) to 631 m (Sohawa), and in Attock District from 285 (Haddowali) to 523 m (Durnal).

Illegal capture and killing of the species

From January 2011 to the end of April 2013 we collected 412 items of evidence of the illegal capture and/or killing of Indian pangolins from 48 locations across all four districts of the Potohar Plateau (Table 1; Fig. 1). The highest number of records of illegal capture or killing were in Chakwal District (n = 156; 13 locations), followed by Attock (n = 149; eight locations), Jhelum (n = 57; eight locations) and Rawalpindi Districts (n = 50; five locations). The highest number of illegal killings occurred in February 2013 (n = 127), followed by September 2012 (n = 92), April 2012 (n = 57) and January 2012 (n = 39) (Fig. 2).

Table 1 Records of illegal capture and killing of the Indian pangolin Manis crassicaudata in the four districts of the Potohar Plateau (Fig. 1) during 2011–2013.

Protected areas

The Indian pangolin has been recorded in eight of the 10 protected areas on the Potohar Plateau (Table 2), with no records in Ayubia or Murree-Kahuta-Kotli Sattiyan National Parks. There are reports of poaching and killing of Indian pangolins in some of these eight protected areas (Table 2).

Discussion

The Indian pangolin was categorized as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List in 2009 but was recategorized as Endangered in 2014 ‘because it is subject to hunting and increasing levels of poaching’ (Baillie et al., Reference Baillie, Challender, Kaspal, Khatiwada, Mohapatra and Nash2014). In Pakistan the species is categorized as Vulnerable (Sheikh & Molur, Reference Sheikh and Molur2004). Under the Punjab Wildlife Acts and Rules (1974) it is included in Category Three of the Third Schedule and is therefore protected throughout the year (Shafiq, Reference Shafiq2005). Despite being protected, however, the species is heavily hunted for trade (Molur, Reference Molur2008), although there is limited evidence of the trade or of threats to the species (CITES, 2000). Data on any hunting and trade are required to design effective conservation strategies for the species. Without conservation efforts the population is likely to continue to decline, and could be lost from the wild in Pakistan. Baseline information about the species’ biology and ecology, including habitat requirements/preferences, population and feeding habits, is also needed to inform conservation efforts.

We found that the species is widely distributed in all four districts of the Plateau and occupies 18% more of the Plateau than previously estimated (Baillie et al., Reference Baillie, Challender, Kaspal, Khatiwada, Mohapatra and Nash2014). It is possible that the species is broadening its range in response to hunting pressure or, more likely, that it was overlooked previously at some sites because of its cryptic nature. Given the species’ low reproductive rate (Roberts, Reference Roberts1997), it could be extirpated from the Plateau without improved protection. Although poachers do not target individuals of a particular sex, 16 of 21 individuals recorded in a separate study were male (T. Mahmood, 2015, unpubl. data). Although this suggests a male-biased sex ratio, the sample size was small, and it is possible that males travel more widely, are more active or are easier to find.

Although pangolins are traded internationally in Asia (Wu & Ma, Reference Wu and Ma2007; Challender et al., Reference Challender, Harrop and MacMillan2015), CITES does not record this trade centrally. Data from seizures of pangolins in Asia (including derivatives, species, and number of individuals in trade) between July 2000 (when zero export quotas for wild-captured individuals of the four Asian pangolin species came into effect) and 2013 indicate the level of trade and provide the most comprehensive means of analysing illicit trade (Rosen & Smith, Reference Rosen and Smith2010; Underwood et al., Reference Underwood, Burn and Milliken2013). Historically, Asian pangolin species have been exploited locally for a range of consumptive uses (e.g. as a protein source, a tonic food, and an ingredient in traditional medicine), most conspicuously in China, but also for the international trade in their scales (Herklots, Reference Herklots1937; Harrisson & Loh, Reference Harrisson and Loh1965). The seizure data and records of trade indicate that between July 2000 and December 2013 there were at least 886 seizures involving pangolins in Asia, with an estimated 227,278 individuals traded illegally (Challender et al., Reference Challender, Harrop and MacMillan2015). The trade was mainly of scales (41%) as well as live and dead individuals (31%) and meat (26%) (Challender et al., Reference Challender, Harrop and MacMillan2015).

There are no reports of consumption of pangolin meat in Pakistan, and the limited local trade in pangolin scales does not account for the large number of pangolins killed. Thus we conclude that the high level of poaching is driven by demand for the international trade. At present, the penalty for poaching the Indian pangolin is a fine of c. PKR 10,000 (c. USD 100) and/or 1 week in prison. This is an ineffective deterrent, as a single adult pangolin may be sold for PKR 50,000 (c. USD 500). Recent population estimates indicate the species has declined by c. 79% (Irshad et al., Reference Irshad, Mahmood, Hussain and Nadeem2015), and that the decline is ongoing. To reduce poaching of the Indian pangolin and protect the population on the Potohar Plateau we recommend increasing the patrol and enforcement efforts and increasing the penalties for poaching. We passed our findings to the local authorities at District level (Punjab Wildlife and Parks Department, Government of the Punjab) and they have increased their efforts to protect pangolins in the study area. There are now fewer reports of pangolin captures. However, this could also indicate that Indian pangolins are continuing to decline on the Potohar Plateau and poachers are finding fewer individuals.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Higher Education Commission, Pakistan, for funding provided through Research Project No. 20–1578/R&D-09/2436.

Author contributions

TM designed the study and secured funding for the research. FA, NI and RH collected field data. TM and FA analysed the data and wrote the article. AA, HF and SA assisted with the analysis and writing.

Biographical sketches

Tariq Mahmood’s research interests include the ecology of mammals, animal physiology, geographical information systems, and toxicology. Faraz Akrim studies the ecology of the Indian pangolin on the Potohar Plateau. Nausheen Irshad is interested in wildlife management and has conducted research on the distribution, population and food habits of the Indian pangolin on the Potohar Plateau. Riaz Hussain conducts research on the ecology of small mammals. Hira Fatima’s interests include the ecology of mammals. Shaista Andleeb is interested in the ecology of small mammals, and has conducted field research on the habitat, distribution and population estimation of the Indian pangolin in Margallah Hills National Park, Islamabad. Ayesha Aihetasham’s interests include biodiversity and entomology.