Introduction

The leopard Panthera pardus has the widest distribution of any wild felid species, ranging from western and southern Africa to the Russian Far East and Java (Stein & Hayssen, Reference Stein and Hayssen2013). This is largely a result of the species' high adaptability, as it can occupy diverse ecosystems ranging from tropical rainforests to boreal forests and arid savannahs (Bertram, Reference Bertram and Macdonald1999) and take a large variety of prey species (Hayward et al., Reference Hayward, Henschel, O'Brien, Hofmeyr, Balme and Kerley2006). Despite these characteristics, the leopard has declined dramatically worldwide (Stein & Hayssen, Reference Stein and Hayssen2013), and disappeared from at least one-third of its historical range in Africa (Ray et al., Reference Ray, Hunter and Zigouris2005). In Asia, leopards have exhibited dramatic declines in the Middle East (Khorozyan, Reference Khorozyan2008; Mallon et al., Reference Mallon, Breitenmoser and Ahmad Khan2008), Russian Far East (Jackson & Nowell, Reference Jackson and Nowell2008), Sri Lanka (Kittle & Watson, Reference Kittle and Watson2008) and Java (Ario et al., Reference Ario, Sunarto and Sanderson2008), and consequently subspecies occupying these regions are categorized as Endangered or Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List. Although the leopard still occupies much of its historical distribution in India (Karanth et al., Reference Karanth, Nichols, Karanth, Hines and Christensen2010), the species' status is unknown across large regions of Asia, particularly in China where data on leopards are outdated and limited.

Historically, the leopard was distributed throughout China, with the exception of the arid Gobi desert and mountainous western regions at elevations > 4,000 m. At present the species reportedly occurs in at least 19 provinces (Bao et al., Reference Bao, Xu, Cui and Frisina2010) and is on the list of fauna for many protected areas. Despite these optimistic reports, there are few recent records in most of these areas (Li et al., Reference Li, Wang, Lu and McShea2010; Jutzeler et al., Reference Jutzeler, Wu, Liu and Breitenmoser2010). Comparisons of several recent leopard surveys with a nationwide mammal assessment carried out during 1995–2000 concluded that most of the existing habitat is no longer suitable and local extinctions have occurred in several regions across the leopard's range (Ran & Chen, Reference Ran and Chen2002; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Hu and Gao2007a,Reference Liu, Gao and Hub, Reference Liu, Zou, Gao, Hua and Liu2009). Therefore it is highly unlikely that the only available estimate of the leopard population in China (1,000; Ma, Reference Ma and Wang1998) is still reliable.

Lack of information on the current distribution and population of a species can undermine conservation efforts, as such information is essential for developing appropriate strategies to maintain viable populations. The aim of our study therefore was to conduct a review of records of the leopard in China from 2000 onwards, to determine the species' current status and distribution and to make recommendations for its conservation.

Subspecies dilemma

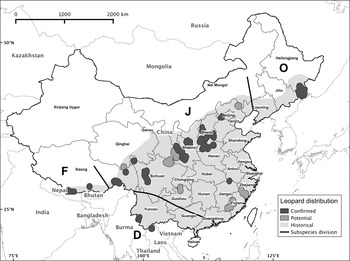

According to phylogenetic classifications (Miththapala et al., Reference Miththapala, Seidensticker and O'Brien1996; Uphyrkina et al., Reference Uphyrkina, Johnson, Quigley, Miquelle, Marker, Bush and O'Brien2001) there are at least three, and probably four, subspecies of leopard in China but their geographical boundaries are unclear. The Amur leopard P. pardus orientalis occupies the north-east, as far south as the area north of Beijing. The Indochinese leopard P. pardus delacouri occurs in the south-east, presumably including all of Yunnan Province and as far north as the Pearl River (Zhu Jiang in Chinese) in Guangxi and Guangdong provinces (Miththapala et al., Reference Miththapala, Seidensticker and O'Brien1996). The most widespread subspecies in China is the north Chinese leopard P. pardus japonensis, commonly referred to as P. pardus fontanierii in the Chinese literature. This subspecies is endemic to China and occurs in the central and eastern regions, presumably as far north as the Beijing area, and as far south as the Pearl River, including Sichuan and Guizhou provinces. The subspecific status of leopards in Xizang (Tibet) Autonomous Region (hereafter, Tibet) is uncertain. Although this population could be P. pardus fusca (Miththapala et al., Reference Miththapala, Seidensticker and O'Brien1996; Uphyrkina et al., Reference Uphyrkina, Johnson, Quigley, Miquelle, Marker, Bush and O'Brien2001), this subspecies has been considered synonymous with P. pardus delacouri in southern China (Smith & Xie, Reference Smith and Xie2008). However, the Tibet population is separated from the main distribution of P. pardus delacouri by high mountain ranges, although the Tibet population occupies similar habitat and shares a continuous distribution with P. pardus japonensis. Genetic research is necessary to clarify the subspecies of the Tibet population; here, we consider it to be P. pardus japonensis. Leopards from south-central Tibet, however, such as those near Mount Everest, are almost certainly P. pardus fusca.

Current distribution

Searches were conducted for newspaper articles, scientific reports and peer-reviewed publications, in English or Chinese, published from 2000 onwards, which contained records of the leopard in China. We searched Google Scholar (2015) for the terms ‘panthera pardus AND china OR japonensis OR delacouri OR orientalis OR fusca’ for 2000–2015, resulting in c. 3,230 items. As this database does not include all Chinese journals we also searched the China National Knowledge Internet (2015) with the keyword ‘jinqianbao’ (‘leopard’ in Chinese) for 2000–2015, resulting in 1,736 items. The titles of items, then the abstracts and finally the full articles were filtered by relevance to our search objectives, reducing the number of items considerably. The corresponding authors of key publications and key felid experts were contacted for additional information. A final total of 28 publications were used (Supplementary Table S1) and seven experts provided additional information as personal communications or unpublished data. Identification of species records from sightings, scats and signs is subject to bias (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Roman and Sunquist2000; Davison et al., Reference Davison, Birks, Brookes, Braithwaite and Messenger2002; Prugh & Ritland, Reference Prugh and Ritland2005; Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Harrington, Hughes, Stirling and Macdonald2009; Laguardia et al., Reference Laguardia, Wang, Shi, Shi and Riordan2015) and therefore extreme caution was adopted when categorizing records (e.g. consideration of the experience of the person making the observation, presence of sympatric carnivores).

The results confirmed the presence of the leopard in 11 provinces (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table S1), in a total of 44 locations where the species has been detected using camera traps, carcasses of poached individuals were recovered, or sightings or scat identifications were made by experienced researchers. Thirty-three of the records were in nature reserves or county forests and 11 in unprotected sites (Supplementary Table S1). An additional six provinces had potential (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table S1) areas of leopard occurrence, based on interviews with local staff, questionnaires to resident communities, livestock depredation reports or habitat quality assessments. In 27 locations the leopard was considered absent (Supplementary Table S1) because no signs were found, although there has been insufficient survey effort in some parts of the historical distribution. Although most camera-trap surveys occurred within protected areas, this is unlikely to bias our results because remaining forest habitat and potential prey species are primarily restricted to these areas.

Fig. 1 The current distribution of subspecies of the leopard Panthera pardus in China: O, P. pardus orientalis; J, P. pardus japonensis; D, P. pardus delacouri; F, P. pardus fusca.

We summarize the records (details in Supplementary Table S1) and distributions for each subspecies (Fig. 1):

Amur leopard P. pardus orientalis

In Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces leopards were probably extirpated by the 1990s (Jutzeler et al., Reference Jutzeler, Wu, Liu and Breitenmoser2010) but recent efforts to create large nature reserves along the Chinese–Russian border have made it possible for individuals to cross into China. Camera traps have recorded leopards in several areas of Jilin Province (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Ma and Zhang2012; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Feng, Zhao, Yang, Dou and Cheng2014a; Beijing Normal University, 2015), and recent sign surveys and camera traps have recorded leopards in south-eastern Heilongjiang Province (Jutzeler et al., Reference Jutzeler, Wu, Liu and Breitenmoser2010; Beijing Normal University, 2015).

North Chinese leopard P. pardus japonensis

In eastern and central China leopard populations are greatly reduced and highly fragmented. Recent camera-trap surveys and other evidence confirmed the presence of the subspecies in only eight provinces (from north to south): northern Hebei, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Ningxia, northern Henan, western Sichuan, southern Qinghai, and Tibet. Most populations in these provinces are small, and occur in isolated protected areas, and it is unknown whether these subpopulations are viable in the long term. Although some records were from outside protected areas, it is probable that these subpopulations function as sinks as a result of the higher human disturbance and lower prey numbers, similar to the situation reported for tigers Panthera tigris in India and Nepal (Karanth et al., Reference Karanth, Gopalaswamy, Karanth, Goodrich, Seidensticker and Robinson2013).

In Hebei Province camera traps recorded leopards in 2013 and 2014, < 150 km from Beijing (T. Song, unpubl. data); the status in other regions of the province is unknown but numbers are likely to be low. Most records were attributed to Shanxi Province, where extensive camera trapping during 2007–2014 identified leopard populations in 16 protected areas across the province (Sohu News, 2003; Song et al., Reference Song, Wang, Jiang, Wan, Cui, Wang and Feng2014; Sina News, 2015; Xinhuanet News, 2015; Z. Zhou, unpubl. data). In the neighbouring Shaanxi Province there were leopard records from six nature reserves in addition to two verified attacks on people and two leopards killed by poachers (Sohu News, 2003, 2006; Li et al., Reference Li, Wang, Lu and McShea2010; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Liu, Cai, He, Songer, Zhu and Shao2012; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wu, Songer, Cai, He, Zhu and Shao2013; Xinhuanet News, 2014; S. Li, pers. comm.). In Ningxia Autonomous Region there were 25 recent records of leopards (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Hu, Wang and Bai2007; CCTV, 2015; China Economic Net, 2015). Leopards also occur in the northern part of Henan Province, where eight leopards were killed during 1999–2007, in addition to multiple sightings and reports of livestock predation by leopards (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Lu, Tang, Liu and Kong2008). Habitat restoration efforts have increased the prey base (mostly hare Lepus sp. and wild boar Sus scrofa) and could have had a positive effect on the leopard population in this area (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Lu, Tang, Liu and Kong2008; Hou, Reference Hou2012).

In Sichuan Province the current status of leopards is unclear, and all recent records are from the west, including camera trap images and fresh scats. Intensive camera trapping is underway (S. Li, pers. comm.) to identify the subspecies' current distribution in the province. During the 1970s and 1980s leopards were recorded in Wolong Nature Reserve (Schaller et al., Reference Schaller, Jinchu, Wenshi and Jing1985; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Wei, Reid and Jinchu1993), one of the largest protected areas in Sichuan, where intensive research on giant pandas Ailuropoda melanoleuca has taken place. However, multiple camera trapping studies during 2005–2009 did not record leopards (Li et al., Reference Li, Wang, Lu and McShea2010) and they are probably extirpated from the reserve. Camera-trapping studies in an additional nine protected areas in central Sichuan during 2002–2009 also failed to record leopards, even though they were on the official mammal lists of the reserves, indicating this species might be extirpated from large areas of the province (Li et al., Reference Li, Wang, Lu and McShea2010; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Hu, Wang, Shang, Zhu, Zhao and Huang2014b). In Tibet leopards were recently recorded in the east (S. Li, pers. comm.). There are also several recent records of leopards from south-central Tibet (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Yao, Huang, Tian, Li and Pu2014), including the forest zone of Mt Everest (Hou, Reference Hou2012). The records from south-central Tibet are probably subpopulations of P. pardus fusca, however. In Qinghai Province, data from local interviews suggested leopards occur in the south (D. Wang, pers. comm.).

There are no recent confirmed records from the other provinces in central or eastern China. In Gansu Province Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Hu and Gao2007a) did not find any leopard sign during an 80-day field survey in key areas during December 2003–March 2004. However, 26 unconfirmed leopard occurrences (reports of leopard tracks and leopard attacks on livestock) were recorded in the last 5 years. The leopard may be extirpated from most of its former range in Gansu and its potential distribution limited to areas on the border with Shaanxi and Sichuan. Leopard tracks were reported in 2006 in south-central Inner Mongolia but there are no other records despite camera traps having been used extensively in this province for studies of Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx and other carnivores.

Leopards appear to have been extirpated throughout all other provinces in central and eastern China, including Hunan, Hubei, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangxi and Jiangxi. In Jiangxi Province one leopard was recorded by a security camera in 2003 or 2004 (S. Li, pers. comm.) but afterwards no further leopards were recorded there despite extensive camera trapping and therefore this population is probably now extirpated (Tilson et al., Reference Tilson, Defu, Muntifering and Nyhus2004). Recent camera trapping surveys did not detect leopards in Hunan (Tilson et al., Reference Tilson, Defu, Muntifering and Nyhus2004; Dahmer et al., Reference Dahmer, Gui and Tian2014; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Su, Li, Wang and Zhang2014) or Guangxi (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Shi, Liu, Zhou and Xiao2014). Based on records of livestock losses, interviews with witnesses and habitat quality, some researchers have suggested that potential leopard populations existed in nature reserves in Zhejiang, Fujian and Guizhou provinces (Ran & Chen, Reference Ran and Chen2002; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Gao and Hu2007b; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zou, Gao, Hua and Liu2009). However, recent camera trapping in several nature reserves in these provinces failed to detect leopards (Tilson et al., Reference Tilson, Defu, Muntifering and Nyhus2004; D. Song, pers. comm.) and the species is probably extirpated from these provinces.

Indochinese leopard P. pardus delacouri

In the south-east this subspecies has recently been recorded in camera traps in two nature reserves in south-western Yunnan Province near the border with Myanmar (The Wildlife Institute, Beijing Forestry University, unpubl. data; Jutzeler et al., Reference Jutzeler, Wu, Liu and Breitenmoser2010) but the population is low (probably < 10 individuals in each reserve) and is unlikely to recover because of the high levels of habitat fragmentation and poaching, and low prey numbers. There are no other recent records of P. pardus delacouri in south-eastern China and this subspecies might be on the verge of extirpation in the country. The distribution and status of this subspecies is currently being assessed in the remaining countries of its distribution (J.F. Kamler, unpubl. data).

Population status and major threats

The previous nationwide estimate of 1,000 leopards (Ma, Reference Ma and Wang1998) is now outdated. The available information that exists is limited to specific areas or nature reserves. Particular effort has been dedicated to surveying for P. pardus orientalis in north-eastern China, using both camera traps and sign surveys, and initial results have suggested a population of 20–25 (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Ma and Zhang2012; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Feng, Zhao, Yang, Dou and Cheng2014a; Jilin Forestry Department, WCS, & WWF, unpubl. data). Additionally, 42 individual Amur leopards were identified during 2012–2014 (Beijing Normal University, 2015; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Feng, Mou, Wu, Smith and Xiao2015), although many of these might be cross-border individuals and not resident leopards. The total number of P. pardus delacouri in south-eastern China is probably < 20. Similarly, the number of presumed P. pardus fusca in south-central Tibet is probably small, also with < 20 individuals.

There are an estimated 60 P. pardus japonensis in Henan Province (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Lu, Tang, Liu and Kong2008; Hou., Reference Hou2012), 20–30 in southern Ningxia (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Hu, Wang and Bai2007), 5–10 in southern Shanxi (Z. Zhou, unpubl. data), 14 in a county forest in northern Shanxi (Song et al., Reference Song, Wang, Jiang, Wan, Cui, Wang and Feng2014), 12 in Fujian (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zou, Gao, Hua and Liu2009), 121 in Guizhou (Ran & Chen, Reference Ran and Chen2002) and < 10 in Zhejiang (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zou, Gao, Hua and Liu2009). There are no estimates available for any of the other provinces or nature reserves. The information collected from articles, reports and personal communications is not sufficient to provide a population estimate for P. pardus japonensis. Therefore, we estimated a population size range for this subspecies based on the number of confirmed leopard locations (33 sites), the mean area of the sites (255 km2) and densities of 1 and 2 leopard per 100 km2. We chose 1 leopard per 100 km2 as a minimum density because that was the estimated leopard density in a 2014 study of leopards in Lishan Nature Reserve in southern Shanxi Province (A. Laguardia, unpubl. data.) and the density reported for leopards in Bhutan (Wang & Macdonald, Reference Wang and Macdonald2009) in similar forested mountain habitat. We chose 2 per 100 km2 as a maximum density to account for the possibility of higher leopard densities in some areas with more favourable habitat and prey numbers. Leopard densities are unlikely to be > 2 per 100 km2 anywhere in China. Our estimates gave a total population of 92–183 for confirmed areas. If we also include potential leopard locations (19 sites, mean area = 433 km2) then the total population estimate is 174–348.

The reasons for the decline of leopard populations and their disappearance from many areas in China have yet to be investigated. Leopards are known to be successful at adapting to altered habitat and can persist as long as there is an adequate prey base, but they cannot withstand intense persecution. Retaliatory killings as a result of human–wildlife conflicts and poaching for the wildlife trade are reported in several provinces (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Hu, Wang and Bai2007, Liu et al., Reference Liu, Hu and Gao2007a, Wang et al., Reference Wang, Lu, Tang, Liu and Kong2008, Xinhuanet News, 2014). In addition, low prey numbers, especially of wild ungulates, are reported even in many nature reserves. Loss and fragmentation of habitat through logging, farming, mining, expanding settlements and road construction are also consistently described as the main threats. Consequently, leopard subpopulations are now more vulnerable because they are small and isolated, with unsuitable habitat between them.

Conservation actions

Panthera pardus is categorized as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List (Henschel et al., Reference Henschel, Hunter, Breitenmoser, Purchase, Packer and Khorozyan2008), although five subspecies, all from Asia, are categorized as Endangered or Critically Endangered. For China assessment of intraspecific taxa is available only for P. pardus orientalis, which is categorized as Critically Endangered (Jackson & Nowell, Reference Jackson and Nowell2008). As a result of the immediate risk of extinction highlighted by our review, we recommend that P. pardus japonensis should have a separate subspecies assessment. With its recent and dramatic range reduction in China, an estimated population of 174–348, and with no subpopulation > 50 individuals, we recommend P. pardus japonensis is categorized as Critically Endangered based on criteria A2b,c and C2a(i) (IUCN, 2012). The China Species List has already categorized Panthera pardus as Critically Endangered and it is a Class I protected species and among 13 particularly important species targeted for conservation and restoration (Wang & Xie, Reference Wang and Xie2004; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Hu and Yang2010).

Compared to other Panthera species, such as the snow leopard Panthera uncia and tiger, leopards receive little attention and limited funding (Jutzeler et al., Reference Jutzeler, Wu, Liu and Breitenmoser2010). The international conservation community in particular has not yet recognized the dramatic decline of this species (Stein & Hayssen, Reference Stein and Hayssen2013), especially in China. To ensure the long-term survival of leopards in China, information about their population dynamics and habitat requirements in relatively small isolated reserves is needed so that effective conservation action can be implemented.

Similar to other large carnivore species, leopards have large home ranges and naturally occur at relatively low densities, requiring large areas to persist. However, their persistence in China will probably be limited to nature reserves as a result of extensive habitat loss and low prey numbers outside these areas. Therefore, to avoid problems related to small and fragmented populations (e.g. inbreeding depression), habitat and leopard prey in nature reserves will need to be restored and expanded. To foster connection between nature reserves, corridors containing suitable habitat need to be established to allow movement and increase gene flow between otherwise isolated populations (Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Sharma, Maldonaldo, Wood, Panwar and Seidensticker2013). Priority should also be given to increasing patrols against poaching. Although it is has been illegal to kill leopards in China since 1988, poaching incidents are still reported, indicating that persecution of the species has yet to be eliminated. National surveys for wildlife are ongoing in China, and our findings, together with new data, will help prioritize conservation efforts and ensure appropriate measures are taken to secure the leopard in China.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the researchers that contributed valuable information on leopard occurrence in China, especially Weidong Bao (Beijing Forestry University), Eve Bohnett (Beijing Forestry University), Ying Chen (Beijing Forestry University), Pengju Chen (Beijing Forestry University), Limin Feng (Beijing Normal University), Yiming Hu (Chinese Academy of Sciences), Dazhao Song (Chinese Felid Conservation Alliance), Dajun Wang (Peking University), Charlotte Whitham (Beijing Forestry University) and the staff of Wocheng Institute of Ecology and Environment.

Biographical sketches

Alice Laguardia's research interests include the conservation of fragmented populations, non-invasive genetic techniques and species distribution modelling. Jan F. Kamler is interested in the conservation of large carnivores and their prey. He is especially interested in how large carnivores affect the ecology of smaller carnivores and their prey, and what effects this has on ecosystems. Sheng Li is a wildlife researcher working on the ecology and conservation of large forest mammals, especially carnivores and ungulates, in south-western China. Chengcheng Zhang is interested in using genetic methods for a deeper understanding of carnivores and their conservation. Zhefeng Zhou is founder of the Wocheng Institute for Ecology and Environment, focusing on biodiversity monitoring and conservation in Shanxi province. Kun Shi, as Secretary-general of the China Cats Specialist Group, is leading a feline research group at the Wildlife Institute of Beijing Forestry University, focusing on conservation of the snow leopard, leopard and tiger.