Introduction

Gender refers to socially constructed characteristics of femininity and masculinity, including cultural norms and roles attributed to women and men. Perceptions of and views on gender vary between societies and can change over time (Zweifel, Reference Zweifel1997; Griffin, Reference Griffin2017). Although gender inequality affects everyone, it can be particularly damaging for women and girls (UN WOMEN, 2017). The development sector has long been systematically addressing gender, aiming to engage and empower women in the context of humanitarian and development interventions. There is evidence of benefits when women are intentionally considered in both policy and activities (Duffo, Reference Duflo2012; Taukobong et al., Reference Taukobong, Kincaid, Levy, Bloom, Platt, Henry and Darmstadt2016). Many development organizations have developed gender policies that have progressed from simply including women and increasing their participation to a more transformative approach. This involves addressing deeply entrenched patriarchal systems, including cultural and traditional norms that underpin and exacerbate gender-based discrimination, exploitation and violence, and making this work an integral component of programmes and projects (e.g. World Vision, Reference World Vision2017; Save the Children, 2019).

Here, we focus on how conservation can better consider women. Although large conservation organizations are developing and refining gender policies and guidance (e.g. IUCN, 2018; The Nature Conservancy, 2018; Conservation International, 2019; WWF, 2011), the environment sector overall, including both conservation and natural resource management, has been slow to address gender inequity. Conservation is defined here as the protection of wild flora and fauna and their natural habitats, and natural resource management refers to the sustainable utilization of major natural resources such as land, water, forests and fisheries (Muralikrishna & Manickam, Reference Muralikrishna, Manickam, Muralikrishna and Manickam2017). There is some evidence in the peer-reviewed literature that engaging women in natural resource management and conservation efforts leads to improved outcomes. Leisher et al. (Reference Leisher, Temsah, Booker, Day, Samberg and Prosnitz2016), for example, cited three studies that identified conservation benefits when women were included. Similarly, a study of natural resource management groups across 20 countries in Latin America, Africa and Asia found that collaboration, solidarity and conflict resolution increased where women were present (Westermann et al., Reference Westermann, Ashby and Pretty2005). Other studies have found that greater representation of women leads to more equitable benefit sharing and improved conservation outcomes in forest conservation programmes (e.g. Upreti, Reference Upreti2001; Westerman, Reference Westerman2014; Vollan & Henry, Reference Vollan and Henry2019). However, this is not always the case, and better conservation outcomes do not always lead to more equitable benefits for women and vice versa. For example, where conservation is undertaken within strongly entrenched patriarchal systems, women who are already excluded from decisions around their land and resources are then also precluded from conservation activities and benefits (Doubleday & Adams, Reference Doubleday and Adams2019). In addition, women are not a homogenous group and issues of intersectionality are important: age, social class, ethnicity and race are among the factors that determine how and which women are involved in conservation. For example, improved enforcement of forest conservation regulations may deliver conservation or forestry benefits, but can disadvantage the poorest, most marginalized people (including women and men) who rely most on these resources (Agarwal, Reference Agarwal2010a).

There are few studies directly measuring the conservation or social benefits of deliberately considering women in conservation. A systematic review of published and unpublished literature found only 17 studies linking gender and conservation (Leisher et al., Reference Leisher, Temsah, Booker, Day, Samberg and Prosnitz2016). Although the publications in our search often included recommendations for how to address gender inequity and better consider women in conservation and natural resource management projects, there was limited evidence in the literature for how this was applied and achieved. We therefore aimed to: (1) examine the existing research on the link between considering women and conservation/natural resource management outcomes, (2) identify the barriers and opportunities that women face in engaging in conservation and natural resource management, and (3) use this analysis to determine research and information gaps and propose a set of recommendations to enable meaningful inclusion of women in conservation and natural resource management.

Methods

We comprehensively reviewed publications dated 1 January 2000–31 January 2020. We searched the Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, USA) and University of Queensland Library (University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia) databases using the following search terms: (‘gender’ OR ‘women’ OR ‘women's empowerment’) AND (‘conservation’ OR ‘biodiversity’ OR ‘natural research management’ OR ‘environmental management’ OR ‘climate change’ OR ‘conservation benefits’ OR ‘decision-making’ OR ‘sustainability’ OR ‘community conservation’ OR ‘development’ OR ‘policy’ OR ‘governance’ OR ‘protected areas’ OR ‘leadership’).

We included in our analysis articles that had been published in a peer-reviewed journal and addressed gender in at least one of three ways: (1) examining if/how the inclusion of women can improve conservation or natural resource management, (2) describing a project in which women are involved in conservation or natural resource management, or (3) providing recommendations for involving women in conservation or natural resource management. We limited our research to articles published in English and focused on women rather than all genders.

We categorized the articles resulting from our search according to the geographical location of the study site. Two authors separately read each article and identified core themes relating to questions around barriers, opportunities and outcomes of women's engagement in conservation and related fields (Letherby, Reference Letherby2011; Patton, Reference Patton2015). The two authors then cross-checked the results to ensure consistency. Where there was disagreement on a theme or category for an article, the two authors discussed this and came to a joint conclusion, which was then verified by the other co-authors.

Results

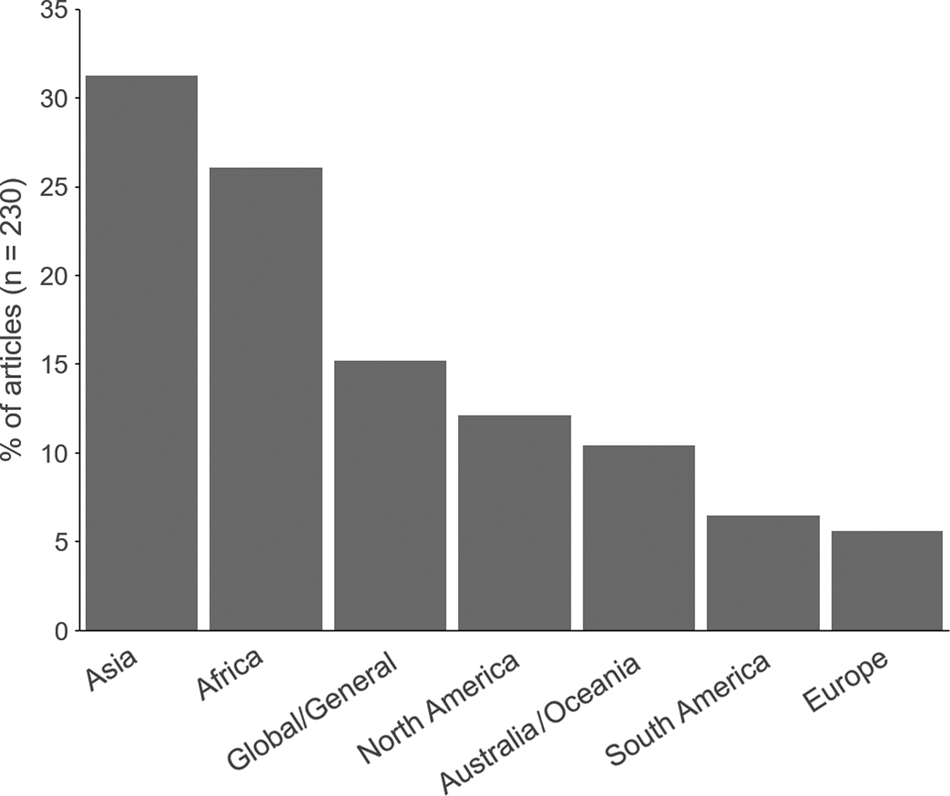

Our search identified 230 articles with information relating to women and conservation or natural resource management (see full list in the references to Supplementary Table 1). The lead author was female in 70% of these articles (n = 160) and male in only 27% (in 3% of articles the gender of the lead author was not determined). Only 17% (n = 40) of the studies focused solely on biodiversity conservation, and over 50% (n = 118) on natural resource management (Fig. 1). Most studies had been conducted in Asia (31%, n = 72) and Africa (26%, n = 60), and only 6% (n = 24) in Australia/Oceania (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 The articles included in our review were classified by sectors relating to environment and conservation. ‘Natural resources’ refers broadly to management of land and agricultural systems, water and water catchments, and oceans and reefs. ‘Other’ refers to some articles that covered women in society, science and/or leadership more generally. Sixty-two articles referred to multiple sectors.

Fig. 2 The articles included in our review were classified by geographical region. ‘Global/General’ refers to articles that referred to global/multi-regional studies or articles not tied to a specific geographical location.

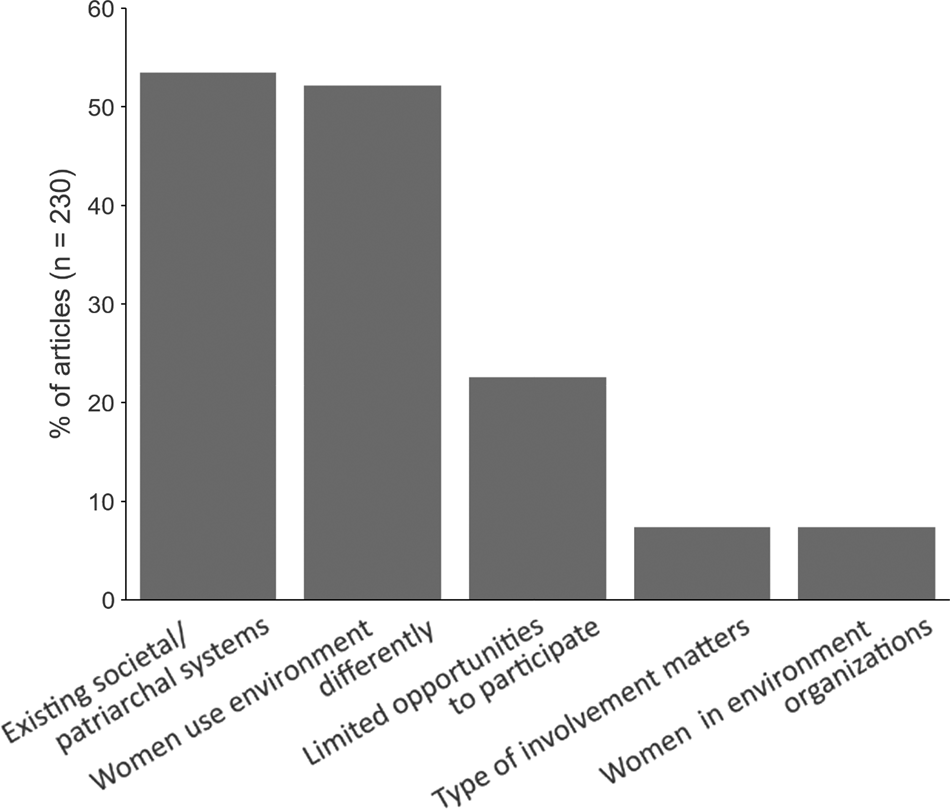

Five themes relating to women in conservation emerged during the analysis of the 230 articles (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1): (1) broader patriarchal, societal and cultural norms affect and generally limit how women can engage in conservation and natural resource management (53%, n = 123 articles), (2) women interact with, use, understand and value the environment differently than men (52%, n = 120), (3) limited resources and capability limit women's opportunities to be involved in conservation and natural resource management (23%, n = 52), (4) women need to substantively and meaningfully included in decision-making to have an impact, which requires dedicated research, effort and resources (7%, n = 17), and (5) patriarchal systems and the inclusion of women need to be addressed more comprehensively within conservation and natural resource management institutions, to understand and address barriers to women's engagement (7%, n = 17; Fig. 3). Ten studies (4%) explicitly measured and demonstrated positive impacts for conservation when women were involved.

Fig. 3 In the analysis of the 230 articles in this review, five broad themes emerged that affect how and why women engage in conservation and management of natural resources.

Discussion

Despite the importance of the issue, only 10 of the 230 studies clearly measured and demonstrated that engaging women in environment and conservation efforts leads to improved outcomes. For example, a study in Bangladeshi wetlands showed that community compliance with resource management regulations was greater when both men and women played an active role in conserving and managing common pool natural resources (rather than just men; Sultana & Thompson, Reference Sultana and Thompson2008). However, several themes emerged relating to barriers and enabling conditions for women to participate in conservation and natural resource management (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1). There were five major themes, all of which are interconnected, and many studies we reviewed covered multiple themes.

(1) Existing societal norms affect women in conservation

More than half of the studies across different countries, ecosystem types and cultural settings reported that women are commonly excluded from decision-making in conservation and natural resource management because of societal or cultural norms. Gender-based (and mostly patriarchal) societal norms shape livelihoods and determine access to and decision-making regarding resources, distribution of benefits and potential social censure for women seeking to access benefits (Buffum et al., Reference Buffum, Lawrence and Temphel2010; Barclay et al., Reference Barclay, McClean, Foale, Sulu and Lawless2018; Essougong et al., Reference Essougong, Foundjem-Tita and Minang2019). This reflects the broader exclusion of women in most societies where men hold primary power and predominate in roles of political leadership, perceived moral authority, social privilege and control of property (e.g. Nuggehalli & Prokopy, Reference Nuggehalli and Prokopy2009; Kleiber et al., Reference Kleiber, Harris and Vincent2018; Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Zheng, Naylor, Murtagh, Waldron and Peng2020).

For example, challenges faced by Tanzanian women in the fisheries sector include societal norms that expect women to carry out most household duties and childcare, leaving limited time for fishing. In addition, there are social taboos allowing men to limit women's access to fisheries (e.g. when women are menstruating; Bradford & Katikiro, Reference Bradford and Katikiro2019). Similarly, forestry research shows that women's roles in forestry management are still restricted by a ‘masculine gender order’ (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Sinclair, Reed and Parkins2011, p. 525) that tends to marginalize women's contributions and participation, especially in leadership and decision-making (Varghese & Reed, Reference Varghese and Reed2012; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Flores, Larson, Marchena, Müller and Pikitle2017; Essougong et al., Reference Essougong, Foundjem-Tita and Minang2019). In addition, projects linking conservation to improving livelihoods have in some cases led to further inequities for women, such as increased workload with limited monetary gain (Kariuki & Birner, Reference Kariuki and Birner2016).

However, although policies from conservation organizations recommend full participation by women, equitable benefit sharing, and promoting women's empowerment in livelihood and conservation projects, there is less evidence in our review of a deeper understanding of the patriarchal systems within which these projects generally operate, and the limitations these place on women's involvement. A gender analysis of grassland management in Mongolia showed that although there is awareness of the need to increase gender equity, women are rarely fully included in decisions and leadership around community land management in herding communities, and this is then reflected in conservation and natural resource management projects (Ykhanbai et al., Reference Ykhanbai, Odgerel, Bulgan, Naranchimeg and Vernooy2006). Therefore, simply having women present in decision-making fora without considering the societal context will not resolve this disparity (Staples & Natcher, Reference Staples and Natcher2015; Baynes et al., Reference Baynes, Herbohn, Gregorio, Unsworth and Tremblay2019).

The failure to adequately address prevailing social norms echoes a broader tendency within the conservation community to pursue biological or nature-based and technical solutions without considering societal inequalities that exist where conservation is focused (Calhoun et al., Reference Calhoun, Conway and Russell2016., Westholm & Arora-Jonsson, Reference Westholm and Arora-Jonsson2018). This could be because conservation researchers and practitioners often lack awareness of societal norms or the skills to address them. Conservation organizations typically invest more heavily in natural science/ecology than social science. Social structures may also be perceived as fixed, or outside the scope of conservation work. Regardless of the cause, social inequalities can inadvertently be compounded by conservation efforts and the result is often that women have less decision-making power, receive fewer benefits from conservation and carry a greater burden of the environmental labour than men (Westholm & Arora-Jonsson, Reference Westholm and Arora-Jonsson2015).

(2) Women interact with, use, understand and value the environment differently than men

Over 50% of articles highlighted that women often interact with, use, understand and value the environment differently than men (e.g. Aswani et al., Reference Aswani, Flores and Broitman2015; Purcell et al., Reference Purcell, Ngaluafe, Aram and Lalavanua2016; Allendorf & Yang, Reference Allendorf and Yang2017; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Passarelli, Lovell and Ringler2018). In marine areas, for example, women commonly undertake inshore fishing, whereas men often undertake coastal and offshore fishing. Therefore, if women are not represented in fisheries decisions and deliberate efforts are not made to acknowledge and incorporate their knowledge, the resources they value are not considered in management planning.

Projects (particularly those linked to the development of livelihoods) may exacerbate inequalities between men and women when their differing use of natural resources is not fully understood or considered. For example, lack of understanding of gender dynamics in the forestry sector in Senegal, and poor representation of women in decision-making around land and forest policy, limits women's access to and control over natural resources, with direct, negative implications for their sources of income and livelihoods (Bandiaky-Badji, Reference Bandiaky-Badji2011).

(3) Women lack resources and/or capability to engage in conservation

There is evidence that limited access to land and resources, for example as a result of insecure land tenure, disproportionately affects women (e.g. Schneider, Reference Schneider2013; St. Clair, Reference St. Clair2016; Dyer, Reference Dyer2018). A study of 240 rural women in Nigeria found that women's limited access to and ownership of land limits their ability to harvest forest resources and provide for their families' needs (Adedayo et al., Reference Adedayo, Oyun and Kadeba2010). Similarly, in Senegal the lack of women's representation on local governance councils has affected women's access to resources, including forestry products, water, education and health services (Bandiaky-Badji, Reference Bandiaky-Badji2011). This also reinforces other societal inequities related to gender, including for example the perception that women are dependent on men (Mukadasi & Nabalegwa, Reference Mukadasi and Nabalegwa2007). Women's lack of access is further exacerbated when natural resources such as water become scarcer as a result of climate change (Djoudi & Brockhaus, Reference Djoudi and Brockhaus2011). In many countries there are also gaps in documented knowledge about women's land rights and access to land (Meinzen-Dick et al., Reference Meinzen-Dick, Quisumbing, Doss and Theis2019).

Gender analyses in countries such as Solomon Islands and Brazil show that although women feel their resources need to be better managed, they may lack access to the information and resources needed to contribute meaningfully to decisions (Di Ciommo & Schiavetti, Reference Di Ciommo and Schiavetti2012; Kruijssen et al., Reference Kruijssen, Albert, Morgan, Boso, Siota, Sibiti and Schwarz2015). In many parts of the world, women and girls have reduced access to education (particularly secondary and tertiary), which can limit their invitation and perceived legitimacy to be part of conservation actions, and their access to positions within conservation and natural resource management organizations. An analysis across Bolivia, Mexico, Uganda and Kenya found the likelihood that a woman would be entrusted with the responsibility of representing the household on a forestry committee increased with her level of education (Coleman & Mwangi, Reference Coleman and Mwangi2013), demonstrating that lack of access to education can be a barrier for women, preventing them from contributing to conservation and natural resource management.

(4) Women need to be substantively and meaningfully included in conservation

Gender-disaggregated data showing the number of women and men involved in conservation and natural resource management are necessary to demonstrate impacts of including women, but looking beyond the numbers we also need to understand how women are involved and what power and agency they have over conservation and resource management (Call & Sellers, Reference Call and Sellers2019; Cook et al., Reference Cook, Grillos and Andersson2019). For example, an examination of forestry conservation programmes in India showed that greater representation of women led to more equitable benefit sharing and improved conservation outcomes, with forest cover in the study areas increasing by 11%. However, for these benefits to be realized, women needed to make up at least 25–30% of the decision-making group (Agarwal, Reference Agarwal2010b). Several authors noted that decision-making bodies need to include at least 30% women for them to effectively influence decisions (Agarwal, Reference Agarwal2010a; Butler, Reference Butler2013).

It is also important to consider the adequacy of the tools being used measure and understand women's role in conservation. For example, household surveys in which only one representative is interviewed can mask substantial differences between genders within the household (Verma, Reference Verma2014). In addition, gender-neutral terms such as ‘fishers’, intended to be inclusive, can mask the different realities of women and men engaged in the fishing sector, or conceal that data are primarily being captured on men's experience (Kleiber et al., Reference Kleiber, Harris and Vincent2014). Therefore, failure to conduct an adequate gender analysis can make it difficult to ensure equitable representation, which then disproportionately disadvantages women (Molden et al., Reference Molden, Verma and Sharma2014). Forestry research in India and Nepal found that although women spend more time than men using and managing forest resources, they face systemic exclusion and denial of benefit from these resources (Aditya, Reference Aditya2016). It is also important that these analyses seek to reflect the complexity of gender, to capture the perspectives of individuals who do not identify within a binary gender concept, reflect intersectionality (Kojola, Reference Kojola2019) and avoid treating women or men as homogenous groups (Westervelt, Reference Westervelt2018). The importance of considering intersectionality is illustrated in a study from Sulawesi, Indonesia, where women's active participation in decision-making appeared to be more limited in mixed-ethnicity communities, compared to more ethnically homogeneous areas (Colfer et al., Reference Colfer, Achdiawan, Roshetko, Mulyoutami, Yuliani and Mulyana2015).

(5) Inclusion of women needs to be addressed within conservation institutions

There are limited published data outlining how conservation organizations consider gender within their own institutions (Jones & Solomon, Reference Jones and Solomon2019), and a tendency to view gender as an issue only for low-income and emerging economies, and community development (Westberg & Powell, Reference Westberg and Powell2015). However, there is evidence of women being excluded within organizations focused on conservation and natural resource management, in external-facing projects and programmes, and in research and policy-setting contexts (Jones & Solomon, Reference Jones and Solomon2019). For example, the number of women occupying leadership positions on many conservation boards in Norway remains small (Lundberg, Reference Lundberg2018), despite research showing the improved environmental performance and financial sustainability of organizations with gender-diverse boards (Glass et al., Reference Glass, Cook and Ingersoll2015; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Conroy, Toppinen, Bull, Kutnar and Panwar2016).

Traditional gender roles are commonly reflected within conservation organizations (Mahour, Reference Mahour2016). For example, women often occupy interpretive, communicative and administrative roles (with a focus on so-called soft skills), and men are over-represented in positions that are more leadership-oriented and risk-taking or involve fieldwork (Westberg & Powell, Reference Westberg and Powell2015; Jones & Solomon, Reference Jones and Solomon2019). This often leaves women performing lower status tasks, rather than playing the roles of scientific experts and decision-makers that are more highly valued and more visible in these organizations (CohenMiller et al., Reference CohenMiller, Koo, Collins and Lewis2020; Westberg & Powell, Reference Westberg and Powell2015). Women also carry out more office housekeeping tasks that are unrelated to their core responsibilities, such as taking notes and organizing and coordinating events (Westberg & Powell, Reference Westberg and Powell2015). This in turn influences how conservation and natural resource management work and research are undertaken, for example which research questions are asked, which work is prioritized and who is considered. We found that 70% of articles relating to gender and conservation had female lead authors, which suggests that these research questions are less likely to be investigated if women are not in research positions.

Conclusion

Research shows that men benefit from and participate in conservation more than women but often there is limited commitment to addressing this (Schneider, Reference Schneider2013; Farnworth et al., Reference Farnworth, Baudron, Andersson, Misiko, Badstue and Stirling2015; Razafindratsima & Dunham, Reference Razafindratsima and Dunham2015). Our review identified significant and persistent barriers to women's full and meaningful participation in conservation and natural resource management efforts. Challenges include heavier workloads around caring and providing for the household (this was evident in every cultural context studied), lack of understanding of the gendered use of resources, and the different access to resources between men and women. There is a persistent perception that men should be the decision makers and leaders in most contexts, both within conservation/natural resource management organizations and in communities where this work is undertaken. There is also limited research on understanding women's aspirations and agency within conservation and natural resource management. Overall, the conservation sector is not yet considering gender equality as an imperative (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2014).

We recommend the following actions to address these challenges: (1) Comprehensive gender and systems analysis should be undertaken prior to and during project and programme implementation, to ensure a nuanced, locally relevant understanding of gender roles and norms, and how these might intersect with conservation and natural resource management efforts (Molden et al., Reference Molden, Verma and Sharma2014). (2) Internal gender audits should be conducted within conservation and natural resource management organizations, which could include setting targets for women's representation in high-status science and leadership positions, noting that women's participation appears to be necessary, but not sufficient, for improved decision-making (Butler, Reference Butler2013). Recommendations from these audits should then be implemented, measured and results reported back to staff and partners. (3) There is also a need to better understand what women's leadership and empowerment means in the context of conservation. This could be addressed at least partially by applying theoretical frameworks from the social sciences that aim to more deeply understand and address gender inequity, power and patriarchy, and the complex interplay of social and cultural norms (Eagly, Reference Eagly2007; Gaard, Reference Gaard2015; van Oosten et al., Reference van Oosten, Buse and Bilimoria2017; Weldon, Reference Weldon, Sawer and Baker2019). (4) Women need to be actively encouraged to lead research and publish their findings. Evidence suggests that gender-diverse research groups produce higher-quality science and are cited more than single-gender groups, yet women researchers may struggle to access the same resources as their men counterparts to conduct and promote their research (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Mehtani, Dozier and Rinehart2013). (5) The conservation sector needs to acknowledge that women are not a homogenous group and that wealth, disability, education, ethnicity, race and other aspects interact to affect women's opportunities to engage in conservation. This requires the conservation sector to draw from the social sciences and humanitarian and development sector. (6) Efforts are required to value women's knowledge, and to enable them to share their knowledge and experience regardless of their formal education. Women often have intimate knowledge of their resources, but lack of formal education limits their access to projects. Specific efforts and resources need to be directed towards engaging women who are excluded from conservation projects because of limited literacy, financial literacy, experience and confidence in the use of tools and technologies. (7) The conservation sector also needs to work directly with men to improve their understanding of the negative impacts of gender inequality and to be accountable in actively addressing these challenges. This is important to mitigate potential risks to women when social and power dynamics are challenged.

This review highlighted significant gaps in how the conservation and natural resource management sector addresses inequity for women. It is vital that the conservation sector prioritizes gender equity both within the organizations that guide and implement conservation work as well as in the places where conservation projects are implemented. This will require affirmative action so that women can both benefit from and influence conservation to the same extent as men.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or commercial or not-for-profit sectors. We thank K. Lyons, H. Possingham and S. Mangubhai and J. Fisher for their guidance, two anonymous reviewers for their critiques, and the Oryx editorial team for their help in finalizing the article.

Author contributions

Study design: led by RJ with LW, BG; data analysis and writing: led by RJ with BG, LW, CL, RK, NB.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Our analysis is based on data collected from other peer-reviewed, published studies. No ethical approval was required for this research, and it otherwise abides by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.