Introduction

Protected areas, including nature reserves and management areas, are established for the effective conservation of biological diversity and protection of the associated natural and cultural resources (DeFries et al., Reference DeFries, Hansen, Turner, Reid and Liu2007; Dudley & Stoulton, Reference Dudley and Stoulton2008). These objectives, however, are often in conflict with socio-economic development. Although many proposals have been put forward to simultaneously satisfy human requirements and maintain ecological functions in protected areas (e.g. Daily & Ellison, Reference Daily and Ellison2012), this is not always feasible because of potential conflicts between conservation and socio-economic development (Coggins, Reference Coggins2000; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Dietz, Carpenter, Alberti, Folke and Moran2007; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Li, Li, Han, Chen and Watkinson2009; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Innes, Wu, Krzyzanowski, Yin and Dai2012).

Human and natural systems are integrated in the sense that people interact with nature (Berkes et al., Reference Berkes, Folke and Colding2000, Reference Berkes, Colding and Folke2008; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Dietz, Carpenter, Alberti, Folke and Moran2007). Local people play important roles in the maintenance of protected areas because of long-standing relationships with these areas (McNeely, Reference McNeely1990; Newmark et al., Reference Newmark, Leonard, Sariko and Gamassa1993; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Chen, Lu and Fu2006), and effective communication and knowledge exchange between various parties are important for management and conservation (Gardner et al., Reference Gardner, Barlow, Chazdon, Ewers, Harvey, Peres and Sodhi2009; Davis & Ruddle, Reference Davis and Ruddle2010; Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Fazey, Reed, Stringer, Robinson and Evely2010). The knowledge held by local communities and people involved in decision making is not usually the explicit and formalized type of knowledge obtained through scientific methods. In China, many protected areas are established and maintained by a strong top-down, command-and-control authority. This limits the opportunities for policy makers, scientists and local participants to cooperate, and hinders knowledge translation and information feedback, possibly leading to unintended results (e.g. Guan et al., Reference Guan, Sun and Cao2011; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zhang, Liu and McGowan2012; Zheng & Cao, Reference Zheng and Cao2015).

The subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forests of south-central China harbour a rich biological diversity (Myers et al., Reference Myers, Mittermeier, Mittermeier, da Fonseca and Kent2000; López-Pujol & Ren, Reference López-Pujol, Ren, Rescigno and Maletta2010; Vanderplank et al., Reference Vanderplank, Moreira-Muñoz, Hobohm, Pils, Noroozi, Clark and Hobohm2014). Many tree species in the region, including Davidia involucrata, Tetracentron sinense, Cercidiphyllum japonicum and Tapiscia sinensis, were once widespread in the northern hemisphere but are now found only in East Asia (Manchester et al., Reference Manchester, Chen, Lu and Uemura2009; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Werger, Ohsawa, Yang and Hobohm2014). Since 1956 national and provincial nature reserves have been established in China to prioritize the conservation of these vulnerable and threatened taxa (Wang & Xie, Reference Wang and Xie2004; Miller-Rushing et al., Reference Miller-Rushing, Primack, Ma and Zhou2016; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Luo, Mallon, Li and Jiang2016). Despite the large number of nature reserves and the significant investment in conservation, many programmes have failed to meet local ecological and socio-economic needs (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Li, Li, Han, Chen and Watkinson2009; Wang & Buckley, Reference Wang and Buckley2010; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Innes, Wu, Krzyzanowski, Yin and Dai2012; Zheng & Cao, Reference Zheng and Cao2015; Qian et al., Reference Qian, Yang, Tang, Momohara, Yi and Ohsawa2016). The increasing rate of habitat loss caused by anthropogenic disturbance has led to poor regeneration of many threatened plant species (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Li, Fritsch, Tian, Yang and Yao2015), highlighting a need for more effective in situ conservation practices. To inform policy makers and improve conservation programmes, nature reserves need to be studied and monitored, with the aim of developing more effective sustainable management frameworks, in China and elsewhere.

We investigated plant communities dominated by D. involucrata in a forest stand subject to intensive management activities in south-central China. Our study site is part of a national nature reserve established to protect first-grade nationally protected trees, including Cathaya argyrophylla and D. involucrata, and has a history of utilization and management of the bamboo Chimonobambusa utilis going back to the Song Dynasty (960–1279). Current management practices for bamboo in this area usually involve clearing away the underbrush to promote the growth of bamboo shoots and facilitate the spread of existing bamboo stands into adjacent vegetation. We examined plant community structure and the regeneration of D. involucrata both in this area and at two additional sites where D. involucrata communities are relatively well protected, to examine the influences of bamboo management on the effectiveness of the conservation of D. involucrata.

Study area and species

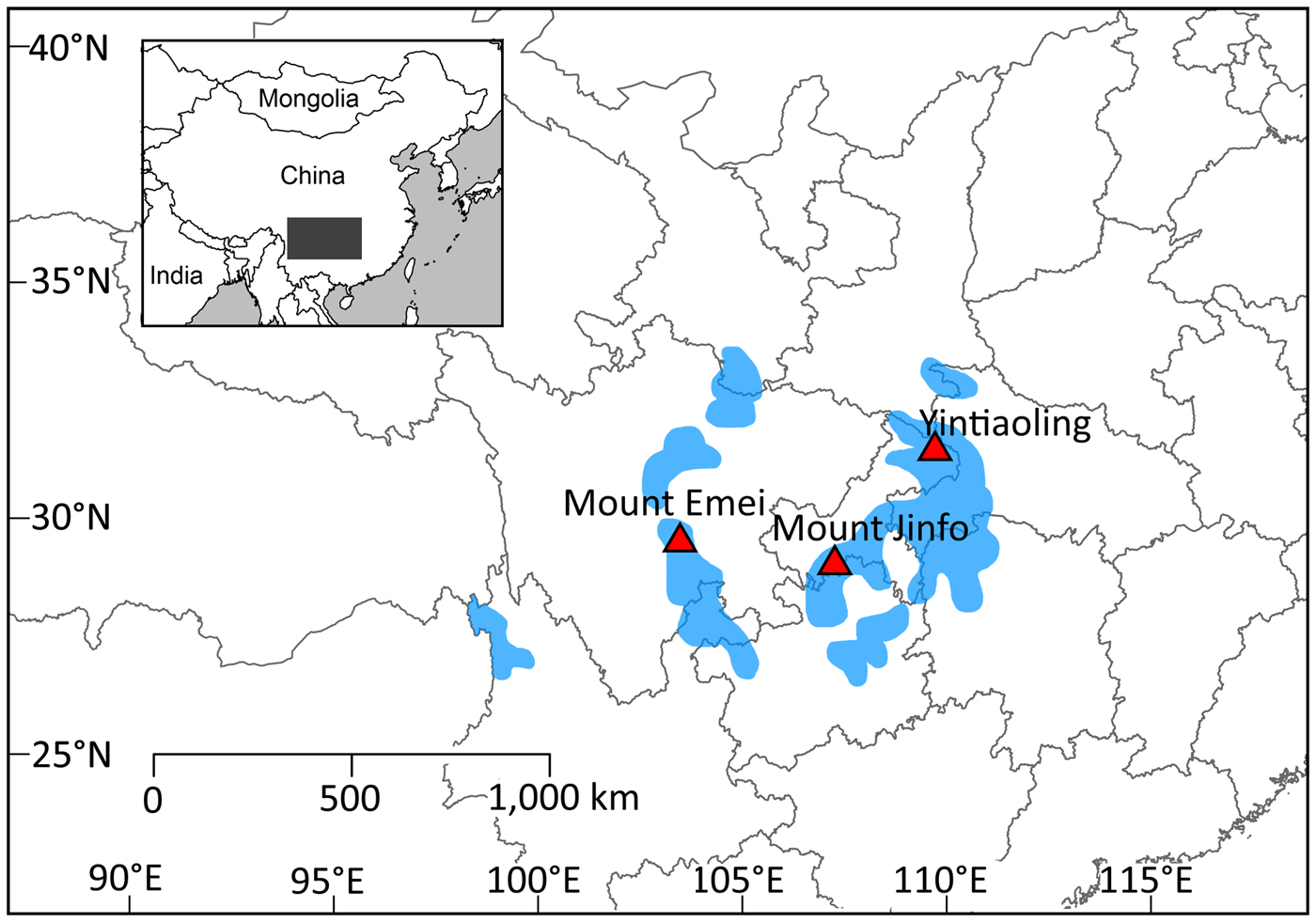

The study site lies in a forest stand on Mount Jinfo in Nanchuan District, Chongqing Municipality (Fig. 1). The area is part of the Mount Jinfo National Nature Reserve, which is a World Heritage site (Ma, Reference Ma2016). Within the study site, D. involucrata and C. utilis have an overlapping elevational distribution (Li, Reference Li2003; Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Tao, Liu and Yong2014) and the intensive management practices used by local people for C. utilis are having an impact on the regeneration of D. involucrata communities. We also selected two additional sites, where the plant communities are also dominated by D. involucrata but are undisturbed by human activities, as a control: one is on Mount Emei in Sichuan Province and the other is in the Yintiaoling Nature Reserve in Chongqing Municipality (Fig. 1). The three sites are all located within the core distribution range of D. involucrata (Fig. 1). The two control sites are not in Mount Jinfo National Nature Reserve because it is difficult to find D. involucrata communities that are undisturbed by human activities within the Reserve. We chose the control sites on the basis that they are (1) at similar latitudes to Mount Jinfo National Nature Reserve (c. 30°N) and thus their climatic conditions should not vary substantially from the study site, and (2) in the core distribution range of D. involucrata and comprise natural and representative D. involucrata communities, based on our field observations.

Fig. 1 The natural distribution of Davidia involucrata in China (shaded area), with the locations of the study sites: Mount Emei in Sichuan Province, and Mount Jinfo and Yintiaoling Nature Reserve in Chongqing Municipality.

Davidia involucrata, also known as the dove tree, was first described by the French priest and naturalist Father Armand David on a trip to China in 1868, and then found again by the Scottish plant hunter Augustine Henry in the Yangtse Ichang gorges. Later, the plant collector Ernest Henry Wilson was employed to find Henry's tree, and he collected a large quantity of seeds and sent them back to England in 1901 (Gardener, Reference Gardener1972). Since 1904 the dove tree has been introduced to Europe and North America, and it is now a popular ornamental tree in parks and gardens. This relict species is endemic to south-central and south-western China, where it occurs in scattered stands on isolated mountain slopes, or in valleys. It was categorized as a first-grade nationally protected species in the Catalogue of the National Protected Key Wild Plants of 1999. Of the 29,716 known angiosperm species in China (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Jia, Zhang and Qin2015), only 33 have been categorized as first-grade protected species in the Catalogue of the National Protected Key Wild Plants of 1999, with 161 species categorized as second-grade protected species. Although D. involucrata has not yet been assessed for the IUCN Red List, it is reported that the natural regeneration of this species is extremely poor (Ma & Li, Reference Ma and Li2005; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Cao, Liu and Liu2008). In addition, there are no indications that the artificial cultivation of D. involucrata for landscaping in cities and botanical gardens has helped this species recover in the wild (Volis, Reference Volis2016), and species distribution modelling has shown that only some areas of the current range of D. involucrata would be maintained under various climate change scenarios (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Dong, Herrando-Moraira, Matsui, Ohashi and He2017).

Methods

The characteristics of the plant communities on Mount Jinfo and in the Yintiaoling Nature Reserve, including size structure and floristic composition, were investigated following the patch sampling method (Ohsawa, Reference Ohsawa1991). We selected several vegetation patches of 100–900 m2, to include representative types of vegetation in the study sites. Within each vegetation patch the species were identified and the height and diameter at breast height (DBH) of every individual (woody species ≥ 1.3 m tall) were recorded. On Mount Jinfo we often found evidence of newly emerging sprouts (usually < 1.3 m) of D. involucrata having been cut and removed (Fig. 2); we marked the damaged trees and counted the number of sprouts cut vs those remaining per individual to quantify the level of damage. On Mount Emei, plant communities were investigated in a permanent plot of 5,400 m2 , as described in Tang & Ohsawa (Reference Tang and Ohsawa2002). Investigations of the D. involucrata communities on Mount Jinfo and in Yintiaoling Nature Reserve were conducted in late summer in 2015, and data on D. involucrata communities on Mount Emei came from a permanent forest inventory reported in Tang & Ohsawa (Reference Tang and Ohsawa2002). We included data on D. involucrata on Mount Emei because, to our knowledge, this site is one of the few sites where the species is well protected and natural regeneration from seeds has been observed.

Fig. 2 The elevational distribution and habitats of the bamboo Chimonobambusa utilis and the dove tree D. involucrata on Mount Jinfo (Fig. 1). (1) Habitat of C. utilis, (2) harvested shoots of C. utilis, (3–5) D. involucrata at flowering, adult and fruit stages, respectively, (6–7) D. involucrata saplings, (8) understorey conditions in D. involucrata populations in managed forest stand, (9) damaged D. involucrata sprouts. Elevational distribution ranges of C. utilis and D. involucrata are based on Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhang, Tao, Liu and Yong2014) and Li (Reference Li2003), respectively. The hatched area indicates the sites where the distribution of C. utilis and D. involucrata overlaps. Photographs 1, 2, 8 and 9 were taken at the study area on Mount Jinfo, and 6 and 7 were taken in the Yintiaoling Nature Reserve (Fig. 1).

The dominant species in each plant community were determined based on the relative basal area of each species (Ohsawa, Reference Ohsawa1984). We used the age–diameter relationship reported in Tang & Ohsawa (Reference Tang and Ohsawa2002) to estimate the ages of main stems or sprouts of D. involucrata when necessary. The mean number of stems of cut and surviving sprouts per adult individual of D. involucrata was compared using a paired t-test.

Results

The characteristics of the forest stands and plant communities in the three sites are summarized in Table 1. The plant communities were all co-dominated by D. involucrata and T. sinense. In addition, they share a number of relict components; for example, Pterostyrax psilophyllus, the co-dominant relict deciduous species in the Yintiaoling Nature Reserve, was also present in plant communities on Mount Jinfo. Tapiscia sinensis, although not a dominant species, was recorded in all plant communities in the three sites. At the two control sites, on Mount Emei and in the Yintiaoling Nature Reserve, the plant communities consisted of some additional relict trees, including C. japonicum and Aesculus chinensis var. wilsonii (Table 1).

Table 1 Habitat characteristics and woody floristic composition of the study site on Mount Jinfo, and the two control sites, on Mount Emei and in Yintiaoling Nature Reserve, China (Fig. 1).

* Only species with relative basal area > 1% are listed. Values in bold indicate dominant species.

On Mount Jinfo the main stems of D. involucrata were mostly of DBH 30–60 cm (Fig. 3a). On Mount Emei and in the Yintiaoling Nature Reserve, however, the DBH of D. involucrata has a continuous, inverse J-shaped distribution (Fig. 3b,c). Small stems of D. involucrata (DBH 0–25 cm; height ≥ 1.3 m) were absent from Mount Jinfo. Based on the generalized age–diameter relationship (Tang & Ohsawa, Reference Tang and Ohsawa2002), the missing smaller stems would have been c. 0–50 years old.

Fig. 3 Frequency distributions of the diameter at breast height (DBH) class for all D. involucrata individuals of ≥ 1.3 m height at the three study sites (Fig. 1).

On Mount Jinfo the number of single-stemmed D. involucrata individuals was approximately equal to the number of multi-stemmed individuals. In contrast, on Mount Emei and in the Yintiaoling Nature Reserve the number of multi-stemmed individuals was higher than that of single-stemmed individuals (Fig. 4a). For newly emerging D. involucrata sprouts on Mount Jinfo, the number of sprouts cut per individual was significantly higher than the number of remaining sprouts (t = −4.792, P < 0.001; Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4 (a) The numbers of single-stemmed and multi-stemmed D. involucrata individuals at each study site (Fig. 1), and (b) the mean numbers of cut and surviving sprouts (newly emerging sprouts at < 1.3 m height) of D. involucrata adults on Mount Jinfo. Whiskers indicate variability outside the upper and lower quartiles, and dots represent data outliers.

The height-class distribution of the D. involucrata on Mount Jinfo had a unimodal pattern, with most individuals in the 16–28 m height-class (Fig. 5a). On Mount Emei and in the Yintiaoling Nature Reserve the height-class distributions were continuous, with the most abundant individuals (of both D. involucrata and co-occurring species) in the shrub and sub-canopy layer (1.3–8 m height-class; Fig. 5b,c).

Fig. 5 Frequency distribution by height-class of D. involucrata communities at the three study sites (Fig. 1). In (a) the co-occurring species do not include C. utilis.

Discussion

Conflict between conservation and socio-economic development

When establishing protected areas in China, recommendations were put forward that both ecological and socio-economic considerations be reviewed in planning management strategies (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Chen, Lu and Fu2006; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Li, Li, Han, Chen and Watkinson2009; Wu, Reference Wu2013). The missing D. involucrata main stems of 0–25 cm diameter at breast height, aged 0–50 years, on Mount Jinfo suggest that the exclusion of D. involucrata seedlings and new recruits in this area may have begun 4–5 decades ago. The size structure of D. involucrata mirrors the transformation of local economic development modes, together with a shift in the government's policy from individual-based management of bamboo stands to a contractor-based management plan (Fig. 6; pers. comm. with local workers and residents, August 2015). Official records show that in June 1965 a major, government-owned forest management centre was established on Mount Jinfo to promote the development and utilization of bamboo. Since then, the bamboo industry in the region has seen rapid development, resulting in increased intensity of bamboo management. In 1986 bamboo products (including bamboo timber and shoots) accounted for an annual revenue of c. USD 65,000. This increased to c. USD 120,000 in 1995, and USD 170,000 in 1998 (The Nanchuan Local Chronicle Editorial Committee, 2014). The harvesting and processing of bamboo shoots on Mount Jinfo has been scaled up to become a major business (the annual value of production in 2015 was c. USD 20 million), in parallel with the implementation of conservation action for D. involucrata (Nanchuan District People's Government, 2016). However, the need to develop a local bamboo shoot market and the existing intensified in situ management practices received little consideration during the establishment of the Mount Jinfo Provincial Nature Reserve in 1979 and the Mount Jinfo National Nature Reserve in 2000, possibly because a one-size-fits-all strategy was being used for establishing and maintaining national reserves in China (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Chen, Lu and Fu2007, Reference Xu, Zhang, Liu and McGowan2012). Bamboo shoot harvesting and processing have become major sources of income for many local residents, and the local government and sponsors in Nanchuan District wish to continue to develop, and invest in, the bamboo shoot market (Nanchuan District People's Government, 2016). Consequently, the ongoing development of the bamboo shoot industry conflicts with the goal of conserving threatened species, such as D. involucrata, in Mount Jinfo National Nature Reserve.

Fig. 6 The current management strategies for bamboo stands and D. involucrata communities on Mount Jinfo (Fig. 1). (1) Relatively balanced coexistence between bamboo and the D. involucrata communities prior to the change in government policy. (2–6) The use of certain measures to accelerate the death of trees other than D. involucrata, which are then used as firewood to boil and pre-process bamboo shoots in situ before they are dried out: (2) trunks of dead trees, (3) firewood made from dead trees, (4) a brick stove to boil and process the harvested bamboo shoots, (5) close-up of the brick stove, (6) processed and then dried bamboo shoots to be sold to the market. (7–8) To promote the growth and production of bamboo shoots and facilitate the spread of existing bamboo stands, understorey shrubs including young D. involucrata sprouts are intentionally cut and removed. (9) Current unbalanced coexistence between bamboo and the D. involucrata communities. The line at the top is a timeline of major events: c. 50 years ago a major, government-owned forest management centre was established on Mount Jinfo to promote the development and utilization of bamboo. Since then, bamboo management policy has changed significantly and the market for bamboo shoots has developed rapidly. In 1979 the Mount Jinfo Provincial Nature Reserve was established to protect species, including D. involucrata, in this area, and in 2000 this nature reserve was designated the Mount Jinfo National Nature Reserve.

The importance of sharing knowledge

To manage forests in protected areas, various forms of knowledge must be integrated (Quesada et al., Reference Quesada, Sanchez-Azofeifa, Alvarez-Añorve, Stoner, Avila-Cabadilla and Calvo-Alvarado2009; Raymond et al., Reference Raymond, Fazey, Reed, Stringer, Robinson and Evely2010). In Mount Jinfo National Nature Reserve the current policy for conserving D. involucrata requires only that large trees be kept alive. Consequently, contractors and local workers focus on promoting the growth of bamboo shoots, the spread of existing bamboo stands, and lowering the cost of bamboo shoot processing. Small seedlings of D. involucrata are removed and the young sprouts are intentionally cut (Figs 4 & 6). The management of other tree species includes ring-barking to accelerate their death. The dead trees are then used as firewood for boiling and pre-processing bamboo shoots in situ before they are dried (Fig. 6). Such measures are informal, and contribute significantly to the absence of small trees (D. involucrata and co-occurring species) in plant communities on Mount Jinfo (Figs 3 & 5).

To integrate professional, ecological knowledge with current management strategies for the forests on Mount Jinfo, relevant parties must understand the life-history characteristics of the key plant species. The plant communities on Mount Jinfo comprise several dominant relict tree species, including D. involucrata and T. sinense (Table 1), and sprouting is a critical part of their life histories (Tang & Ohsawa, Reference Tang and Ohsawa2002; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Peng, He, Ohsawa, Wang and Xie2013). In the absence of seedlings, sprouts are crucial for sustaining the recruitment and regeneration of the species in this forest. The gap in the 0–25 cm DBH class for D. involucrata on Mount Jinfo (Fig. 3a) confirms the significant lack of recruits from seedlings, and emphasizes the importance of sprouting for maintaining D. involucrata. As most of the newly emerging sprouts of D. involucrata are intentionally cut, this forest may be facing a future ecological crisis of structure and function.

In the unmanaged forest stands on Mount Emei the ability of relict deciduous trees such as D. involucrata to sprout and thus adapt to unstable habitats (e.g. scree slopes) enables them to avoid competition with coexisting evergreen trees, which generally establish themselves in stable environments such as on mountain ridges (Fig. 7a; Tang & Ohsawa, Reference Tang and Ohsawa2002). Management activities such as selectively cutting neighbouring trees, when carried out at low intensity, can improve understorey light conditions and thus promote the regeneration of remaining D. involucrata individuals in the plant community. This may explain how, despite the long history of utilizing and managing bamboo on Mount Jinfo, D. involucrata persists. However, there is a threshold of intensity of bamboo management above which increasing management will have negative effects on the regeneration of D. involucrata because of an increase in interspecific competition (e.g. competition between D. involucrata and bamboo for light and below-ground resources; Takahashi et al., Reference Takahashi, Uemura, Suzuki and Hara2003; Kisanuki et al., Reference Kisanuki, Kudo and Nakai2012) (Fig. 7b). Hence, in the long term, control of management intensity would benefit those involved in bamboo harvesting whilst minimizing the negative effects of these activities on the forest.

Fig. 7 (a) Regeneration strategies for relict trees and coexisting evergreen species in a typical relict plant community (revised from Tang & Ohsawa, Reference Tang and Ohsawa2002). (b) Changes in the effect of bamboo management intensity on D. involucrata regeneration; the dotted circle shows the possible effects of management activity on the regeneration of D. involucrata at a medium level of management intensity, and the dashed arrow indicates the direction towards which the effects will change as the management intensity increases. The peak of the curve represents the optimum management intensity for the regeneration of D. involucrata. As management intensity increases beyond the point of intersection between the dashed line and the curve, the net effects of human activity on the regeneration of D. involucrata shift from positive to negative.

Lessons learned for tree conservation

Tang et al. (Reference Tang, Yang, Ohsawa, Momohara, Hara, Cheng and Fan2011) investigated the structure and regeneration of natural populations of the conifer Metasequoia glyptostroboides in Hubei, south-central China and found a substantial portion of the seedlings and small trees were missing. As in the case of D. involucrata on Mount Jinfo, only adults of M. glyptostroboides are officially protected. Seeds have been collected for sale and seedlings have been moved to non-native habitats as landscape plants, leaving the understorey space as agricultural land for cultivating Coptis chinensis, a medicinal herb (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ma, Guo, Fan and Tan2005; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yang, Ohsawa, Momohara, Hara, Cheng and Fan2011). Although the remaining adults of M. glyptostroboides and D. involucrata may survive in protected areas for several decades under current conservation practices, long-term persistence cannot be guaranteed without effective reproduction and recruitment. In contrast, populations of Ginkgo biloba, also endemic to China, have continuous size and age structures because local traditional beliefs have protected the seedlings, saplings and habitat of this speceis (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yang, Ohsawa, Yi, Momohara and Su2012). Thus, management for maintenance of regeneration and recruitment is critical not only for the conservation of D. involucrata on Mount Jinfo but also for other threatened and highly valued species that may have similar life-history characteristics to D. involucrata.

Acknowledgements

We thank Qiuping Tan, Ting Li, Mei Pang and Jing Xiao for help with the field work, and Xiaoya Li of the Fauna & Flora International China Programme for helpful discussions, and Martin Fisher, Cella Carr, Bo Chen and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments which contributed significantly to improving the quality of the manuscript. This study was supported by grants from the Key National Research and Development Plan Program (2016YFC050310203) to YY, the Special Funding for Postdoctoral Researcher of Chongqing (Xm2016083) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2016M592635) to SQ, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Project No. 106112016CDJXY210006) to LZ, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31500355) to KS.

Author contributions

YY and SQ designed the study. SQ analysed the data and wrote an initial draft of the article. YY, CQT, SQ, LZ and SY conducted the field work and collected the data. All authors contributed substantially to the development of the article.

Biographical sketches

Shenhua Qian's research focuses on population dynamics and the conservation of biodiversity. Cindy Q. Tang' research interests include the conservation of relict species and the origins and development of subtropical forests. Sirong Yi's research interests include forest conservation and management. Liang Zhao is interested in the relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Kung Song's research focuses on the processes and mechanisms structuring the plant communities in subtropical forests. Yongchuan Yang's research interests incorporate many aspects of the conservation of relict species. He also has a special interest in biodiversity patterns in urban ecosystems.