The problem of how to reduce or eliminate crop losses to wildlife is common to farmers everywhere (Conover, Reference Conover2002). Where agriculture is central to sustaining rural livelihoods crop-raiding may be perceived as a fundamental factor affecting peoples’ livelihood security (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Osborn and Plumptre2002). In tropical Africa farmers employ both lethal and non-lethal methods to protect crops from wildlife, including guarding, fencing, chasing, hunting, trapping and poisoning (Osborn & Hill, Reference Osborn, Hill, Woodroffe, Thirgood and Rabinowitz2005). Some potentially lethal methods are non-selective, causing injury or death to both target and non-target animals. The impact of such methods on threatened wildlife is poorly understood. Across Africa great apes increasingly range within human-modified, cultivated landscapes and raid crops (Hockings & Humle, Reference Hockings and Humle2009; Hockings & McLennan, Reference Hockings and McLennan2012). This exposes them to potentially lethal crop-protection methods.

Landscapes surrounding Uganda's protected areas are characterized by expanding, high-density agricultural communities and rapid conversion of unprotected habitat for farming (Mwavu & Witkowski, Reference Mwavu and Witkowski2008; Naughton-Treves et al., Reference Naughton-Treves, Alix-Garcia and Chapman2011). Crop-raiding is a primary concern of farmers throughout western Uganda (Hill, Reference Hill2004; Hartter, Reference Hartter2009; Ferrie et al., Reference Ferrie, Bettinger, Kuhar, Lehnhardt, Apell and Kasoma2011). Among the crop protection methods employed are large steel jaw traps, here referred to as mantraps. These consist of parallel jaws held open by a spring mechanism and tethered by a chain to the ground or a tree (Plate 1). Measuring 40–60 cm in length and weighing 10–15 kg or more, they are larger and heavier than gin traps or leg-hold traps used to capture or kill wildlife elsewhere; e.g. foxes Vulpes vulpes (Englund, Reference Englund1982), coyotes Canis latrans (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Gruver and Williams1996) and possums Trichosurus vulpecula (Warburton & Orchard, Reference Warburton and Orchard1996). While extensive data exist on use of such traps for research and management, particularly in North America and Europe (Iossa et al., Reference Iossa, Soulsbury and Harris2007), we are unaware of studies detailing use of large jaw traps for crop protection by rural African farmers outside Uganda.

Plate 1 A large steel mantrap used to kill or maim crop-raiding animals and/or procure meat.

Mantraps are often concealed beneath soil or vegetation along forest edges; when stepped in the jaws snap shut, firmly entrapping the animal's limb. Owing to their size and strength, they inflict severe injury or eventual death even to large mammals (Munn & Kalema, Reference Munn and Kalema1999–2000). Mantraps are illegal but laws are not currently enforced. Although sometimes used to procure meat they are also used to kill or maim crop-raiding mammals, particularly baboons Papio anubis, wild pigs Potamochoerus sp., tantalus monkeys Chlorocebus tantalus and porcupines Hystrix cristata (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2005). It is important to distinguish mantraps placed around fields by farmers from snares set by hunters to catch forest game. Here the term trap refers specifically to mantraps.

Primates are not traditionally hunted for meat in Uganda. Nevertheless, crop-raiding chimpanzees face harassment and occasional retaliatory hunting from humans (McLennan, Reference McLennan2008; Hyeroba et al., Reference Hyeroba, Apell and Otali2011). Additionally, several instances of entrapped chimpanzees have been reported in the forest–agriculture matrix surrounding the Budongo Forest (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2005). In one documented case an adult male chimpanzee, unable to free his hand from the trap, succumbed to septicaemia 1 week later (Munn & Kalema, Reference Munn and Kalema1999–2000). Here, we report new cases of chimpanzees in mantraps in the greater Budongo landscape. Where possible veterinary interventions were attempted because mantraps cause serious injury (e.g. loss of limbs) or death if not removed, chimpanzees are Endangered and legally protected, and it is a human-caused problem.

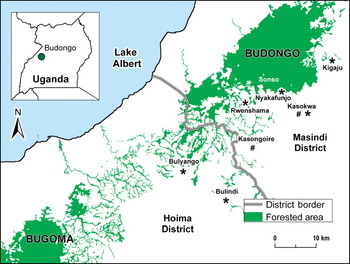

Budongo Forest Reserve supports one of Uganda's largest chimpanzee populations (>500 individuals; Plumptre et al., Reference Plumptre, Rose, Nangendo, Williamson, Didier and Hart2010; Fig. 1). South of the Reserve, chimpanzees inhabit remnant forest patches across a cultivated landscape of > 600 km2. These small forests are being extensively logged and cleared for farming (McLennan, Reference McLennan2008; McLennan & Plumptre, Reference McLennan and Plumptre2012). Chimpanzees traverse farmland between fragments and raid crops throughout this forest–agricultural matrix. Between 2007 and July 2011 we received 10 reports of chimpanzees in mantraps in this region (Table 1; Fig. 1). Eight were reported to us by local residents. Although nine cases occurred in forest–farm ecotones outside Budongo, including five at one site (Bulindi), one fatal entrapment at the reserve border involved a chimpanzee from a study community within Budongo (Case 8, Table 1). Known victims included adult males, adult and subadult females, and a juvenile male. Although most were probably trapped inadvertently, there was some indication that crop-raiding chimpanzees were targeted intentionally (Cases 1 and 2).

Fig. 1 Budongo Forest in the Masindi District of western Uganda and the nearest main forest block to the south-west, Bugoma Forest (in Hoima District). Small riverine forest patches occur throughout the intervening region, which is heavily cultivated. Most forest patches are unprotected and are being cut down. Multiple eastern chimpanzee Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii communities inhabit this forest–agricultural mosaic (McLennan, Reference McLennan2008). Place names indicate locations of known chimpanzee trappings: *, trap locations reported in this study (Table 1); #, trap locations reported previously (Munn & Kalema, Reference Munn and Kalema1999–2000; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2005). Adapted from a vegetation map provided by Nadine Laporte of the Woods Hole Research Center's Africa Program and WCS–Kampala. The inset indicates the location of Budongo in Uganda.

Table 1 Description of 10 cases of eastern chimpanzees Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii caught in large metal mantraps around the Budongo Forest, Uganda during 2007–July 2011.

1 Non-government organizations involved in attempted interventions: BCFS, Budongo Conservation Field Station; CSWCT, Chimpanzee Sanctuary and Wildlife Conservation Trust; JGI, Jane Goodall Institute

2 ‘Satisfactory recovery’ reported if follow-up observations indicated the wound caused by the trap had healed and the animal was feeding without difficulty and interacting socially with other group members

3 An earlier, fatal case of chimpanzee entrapment at Kasokwa was reported by Munn & Kalema (1999–2000)

Veterinary interventions were attempted in seven cases, in six of which chimpanzees were successfully anaesthetized, traps were removed and wounds treated (Plate 2). Although these individuals were not well habituated, limited follow-up observations indicated a satisfactory recovery in at least five cases, including one subadult female that sustained severe injuries (Case 6). One intervention was abandoned because of potential risks involved in darting and because the situation was judged non-life threatening (Case 7). In the remaining cases information about a trapping was received from local people after a delay of ≥ 1 week, by which time the whereabouts of chimpanzee victims was unclear (Cases 1 and 2), or the chimpanzee had already died (Case 8).

Plate 2 Right arm of an adult male chimpanzee Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii caught in a steel mantrap in an unprotected forest fragment in Bulindi, January 2011 (Case 9, Table 1). The chimpanzee has been anaesthetized so that the trap can be removed and the wound treated.

Our observations indicate a conservation problem requiring urgent attention. Although several chimpanzee fatalities from mantraps have been recorded previously (Munn & Kalema, Reference Munn and Kalema1999–2000; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2005), reports of trappings have increased around Budongo since 2007, probably because of greater engagement of local communities by conservation organizations. For example, the five cases reported from Bulindi reflect the fact that chimpanzees there were subjects of an 18-month research project (McLennan & Hill, Reference McLennan and Hill2010) and NGOs have worked closely with villagers since 2007. Four of five other cases were reported from locations where residents have regular contact with conservation workers and/or researchers. There is no suggestion that farmers at these sites are especially likely to use mantraps. Elsewhere in the forest–agriculture matrix trappings probably go unreported and chimpanzee victims may die. We expect the cases reported here represent only a portion of actual trappings in the region. Whether the rise in reported cases also reflects increased use of traps by farmers is unclear. Landscapes surrounding Uganda's protected areas are undergoing major changes in land-use cover. The area south of Budongo has experienced rapid human population growth and unsustainable agricultural expansion, including a 17-fold increase in commercial sugarcane plantations during 1988–2002, associated with an 8.2% loss of forest/woodland cover (Mwavu & Witkowski, Reference Mwavu and Witkowski2008). Forest patches have been further degraded by uncontrolled logging (McLennan & Plumptre, Reference McLennan and Plumptre2012). Across this region villagers report seeing chimpanzees on cultivated land (McLennan, Reference McLennan2008). Therefore, a diminishing tolerance of wildlife, including chimpanzees, could potentially have led to more farmers setting traps.

More data are needed to quantify the impact of traps on chimpanzees regionally. Currently, few populations are monitored. At least five chimpanzees were trapped within 4 years at Bulindi, c. 20% of this small population or c. 30% of adult and subadult community members (McLennan & Hill, Reference McLennan and Hill2010). Without rapid veterinary intervention to remove traps many victims will die. Consequently, mantraps probably represent a significant source of chimpanzee mortality in forest–farm mosaics in this region. Our data also confirm that chimpanzees in large, protected areas such as Budongo occasionally step in traps when entering adjacent farmland. These observations demonstrate that wildlife authorities and conservation organizations must consider the techniques used by rural farmers to protect their livelihoods from wild animals. There is an urgent need for a targeted strategy to address the mantrap problem in Uganda, as was developed to tackle illegal snaring (e.g. Babweteera et al., Reference Babweteera, Reynolds, Zuberbühler, Wrangham and Ross2008). Priority must be given to law enforcement, education and support for improved non-lethal crop protection to reduce human–wildlife conflicts.

Acknowledgements

Interventions were carried out with the approval and assistance of the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA). For assistance we thank Peter Apell, Lilly Ajarova and the Chimpanzee Sanctuary and Wildlife Conservation Trust, Gerald Mayanda and Tom Sabiiti, and residents of sites mentioned in this article. We thank Tonny Kidega for additional information and Kim Hockings for helpful comments. Kevin Langergraber, Linda Vigilant and Carolyn Rowney conducted DNA analysis that identified the dead chimpanzee from Sonso. The President's Office, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and UWA gave permission for MM to work in Uganda. His research was supported by ESRC/NERC and a Leverhulme Trust award to Catherine Hill (Project reference: F/00 382/F).

Biographical sketches

Matthew McLennan’s research concerns the interactions between humans and wildlife, and the challenges of conservation outside protected areas, with a special focus on great ape–human sympatry in Africa. David Hyeroba is a veterinarian with the Jane Goodall Institute and Kibale Ecohealth Project. He investigates pathogen transmission between humans and primates. Caroline Asiimwe is a veterinarian with the Budongo Conservation Field Station. Her work focuses on protecting chimpanzee populations in their natural habitat and resolution of human–wildlife conflicts at the forest–agriculture boundary. Vernon Reynolds founded the Budongo Forest Project. One of his main concerns is how to reduce the number of chimpanzees maimed or killed by snares, traps and weapons used by people guarding crops. Janette Wallis is the Director of the Kasokwa Forest Project and focuses on the behavioural ecology of primates in small forest fragments. She is also the Vice President for Conservation of the International Primatological Society.