1. Introduction

The notion of morphomes, alternatively morphomic patterns, goes back to Aronoff (Reference Aronoff1994).Footnote 1 In brief, morphomes are morphological (inflectional) patterns without complete motivation from outside of morphology. They include, among other things, inflection classes and cases of systematic formal identity not completely motivated by semantics, syntax or phonology.Footnote 2

An example is Maiden’s (Reference Maiden2018) ‘L-pattern’. For some Romance verbs, certain cells in the paradigm – the 1.sg present indicative and the entire present subjunctive – share a distinctive root allomorph that is not shared with the rest of the paradigm. Table 1 illustrates the pattern for the Portuguese verb ter ‘have’. The shading indicates the similarity with an ‘L’; the sequence nh is pronounced /ɲ/.

Table 1. The L-pattern in Portuguese. Shading marks cells sharing a root.

There is probably no synchronic reason for this formal identity – or any correlation with a natural class. Yet speakers must have noticed the identity in form, as there is abundant diachronic evidence for the productivity of the L-pattern. Independently of the particular material that may fill the particular cells, there is a pattern of identity. Another example is the so-called N-pattern in Romance, where the forms of the first, second, and third persons singular, and of the third person plural, in the present indicative, present subjunctive, and imperative, share formal characteristics not found elsewhere in the paradigm of the verb. Again, there is probably no semantic or syntactic reason, synchronically, for the formal similarity.

Aronoff (Reference Aronoff1994:46) calls morphomic patterns ‘pure form’ and even ‘useless’. It does indeed seem useless for purposes outside of morphology that the shape of one particular member of the paradigm should signal, as it were, the shape of another member of the paradigm.Footnote 3 However, given the generality, diachronic persistence and productivity of e.g. the L- and the N-pattern, ‘useless’ may be a rhetorical excess. For speakers, there can be a ‘paradigm cell filling problem’ (Ackerman, Blevins & Malouf Reference Ackerman, Blevins and Malouf2009) – how does one know what morphological material fills a certain cell? How do speakers of Portuguese know which stem to select for the 1.pl subjunctive of ter? A morphomic pattern is usually helpful because it usually is predictive (Blevins Reference Blevins2016:106; Maiden Reference Maiden2018). Once we know the Y, the X will be deducible; once we know that the stem of the 1.sg indicative is tenho, we can confidently deduce that the 1.pl subjunctive is tenhamos, and vice versa.

To repeat, morphomic patterns are morphological templates. Their theoretical importance lies in not being fully motivated by factors outside of morphology. Aronoff’s (Reference Aronoff1994) monograph was written in an intellectual climate in which constant efforts were made to reduce morphology to syntax, phonology or both. Distributed Morphology (e.g. Embick & Noyer Reference Embick, Rolf, Gillian and Charles2007, Siddiqi Reference Siddiqi2019) is a product of such a climate. In that framework, there is (in Spencer’s Reference Spencer2019 words) no such thing as morphology. For Aronoff, by contrast, morphology is a real and important facet of language. It is in order to argue this point that he launches the ‘morphomic’ approach. The claim that there is a morphomic level is a claim that morphology has patterns of its own; neither fully reducible to nor fully predicted by anything outside of morphology.

By now, there is a large literature on morphomic patterns in Romance. See, for example, Maiden (e.g. Reference Maiden, Geert and Jaap2005, Reference Maiden2013, Reference Maiden2016a, Reference Maiden, Adam and Martin2016b, Reference Maiden2018, Reference Maiden2021), Smith (Reference Smith2011, Reference Smith2013), Loporcaro (Reference Loporcaro2013), O’Neill (Reference O’Neill2013, Reference O’Neill2014), Esher (Reference Esher2014, Reference Esher2015a, b, Reference Esher2016), and Herce (Reference Herce2019, Reference Herce2020b). The notion has been discussed also for other languages, including Greek (Sims-Williams Reference Sims-Williams2016), Sanskrit (Stump 2016), English (e.g. Aronoff Reference Aronoff1994, Blevins Reference Blevins2016), German (e.g. Carstairs-McCarthy Reference Carstairs-McCarthy2008, Demske Reference Demske, Albrecht, Hans-Walter, Klaus and Andreas2008, Dammel Reference Dammel2011, Nübling Reference Nübling, Sarah and Sandra2016), Kayardild (Tangkic, Australia; Round Reference Round2016), Kiranti (Sino-Tibetan, Nepal; Herce Reference Herce2021), Chichimec (Oto-Pamean, Mexico; Feist & Palancar Reference Feist and Enrique2021), to mention but a few. Yet studies of morphomes outside of Romance have been relatively fewer, and some linguists remain sceptical (see Section 3 below).

Therefore, a broader typological perspective is needed. In an important recent thesis, Herce (Reference Herce2020a:25) observes that ‘a greater empirical understanding of unnatural morphological patterns will be valuable for both defenders and detractors of autonomous morphology’. Herce’s work, in which 117 morphomic patterns from a large number of language families are surveyed, is a large step forward and, together with Maiden’s work, inspiration for this paper.

It has become common (following Round Reference Round, Matthew, Dunstan and Greville G.2015) to talk of rhizo-morphomes and meta-morphomes.Footnote 4 The terminology may seem forbidding, but the idea is not. Rhizo-morphomes are traditional inflection classes (‘lexeme A inflects like lexeme B, while C and D inflect in another way’). Meta-morphomes are syncretisms, either between words (‘the nominative singular of lexeme X is formally identical to the dative plural of X’) or between parts of words (‘the genitive singular suffix of lexemes E, F, G … is identical to the nominative plural suffix of lexemes H, I, J’).

Meta-morphomic patterns are the object of this paper. They have been in focus in Maiden’s numerous important contributions. While Romance paradigms may represent more fertile hunting-ground for the enthusiast, the purpose of this paper is to present fairly clear-cut examples of meta-morphomes in North Germanic. Herce (Reference Herce2020a:122) has already suggested a case in the Icelandic verb inflection (see Section 2.1 below). He argues that morphomes are present across the world’s languages (Herce Reference Herce2020a:359), but also that they are relatively infrequent (Herce Reference Herce2020a:346).

With the exception of Herce’s work, not much has been done on possible morphomes in North Germanic, but some examples of rhizo-morphomes have been suggested (Enger Reference Enger2019a, b). The purpose of Section 2 below is to suggest some further candidates for the morphome label in North Germanic, more specifically meta-morphomic patterns, syncretisms. In Section 3, we consider, briefly, some alternative analyses and some larger theoretical issues. Section 4 presents the conclusions.

2. Candidates

We begin with a morphomic pattern in the verb inflection recently highlighted by Herce (Reference Herce2020a) (Section 2.1). After two other candidates in the verb inflection (Sections 2.2–2.3), we look at one in the noun inflection (Section 2.4) and one in the adjectives (Section 2.5). The aim is to present reasonably clear candidates for the label ‘meta-morphome’. Our focus, within North Germanic, is mainly on Norwegian, a language with a ‘gap’ in its written records for more than three centuries. So some readers (including one reviewer) might wish for more philological detail than has been possible. The argument for the morphomes being noticed by speakers has to do with their diachronic productivity.

2.1 Infinitive and (3rd) plural, present tense

Old Norse (ON, also known as ‘West Norse’) is an idealised version of the language spoken in Norway and on Iceland and the Faroe Islands around the year 1200 (see e.g. Barnes Reference Barnes2008); it is a branch of North Germanic. Below, we ‘pretend’ that ON is the ancestor also of Swedish. Historically speaking, that is wrong, but for present purposes, it is a harmless pedagogical simplification. (ON and Old Swedish had much in common on the points of interest in the present paper.)

In ON, the infinitive and the present plural 3rd person are formally identical. Herce (Reference Herce2020a:122) traces the historical background, arguing that this is a morphome. There is syncretism even when the exponents differ. For most verbs, both forms will end in an -a; for example, the ON infinitive baka ‘bake’ is formally identical to present plural 3rd person baka, infinitive detta ‘fall’ is formally identical to present plural 3rd person detta.Footnote 5

Herce (Reference Herce2020a) shows what happens later in Faroese and Icelandic. We shall consider Norwegian and Swedish, generally less ‘conservative’ languages, morphologically. In post-ON stages of those languages, the 3.pl form has ‘taken over’ the entire set of plural cells, so that the syncretism is between the infinitive and the present plural. In East Norwegian, the suffix has for most verbs been changed into another vowel while for some few (simplified, those that had a CV root before the suffix in ON), it is still -a. This is a phonological change (in Norwegian called jamvektsregelen, in Swedish vokalbalans; see e.g. Kristoffersen & Torp Reference Kristoffersen, Arne and Helge2016, Riad Reference Riad, Oskar, Kurt, Ernst, Allan, Hans-Peter and Ulf2005, respectively). So in the Halling dialect, a conservative East Norwegian dialect, the verb baka ‘bake’ will retain formal identity between infinitive and present plural /baːka/, and the verb detta ‘fall’ will retain formal identity between infinitive and present plural, but with a different suffix /detæ/ (Venås Reference Venås1977).

There is no obvious syntactic or semantic argument for uniting the infinitive and the present plural against the present singular. This may therefore seem a good candidate for a morphomic pattern, also at a later stage than the one surveyed by Herce. Yet speakers do not necessarily notice a pattern that is obvious to trained linguists (see e.g. Joseph Reference Joseph and Peter2011, Sims-Williams & Enger Reference Sims-Williams and Hans-Olav2021). The formal identity is inherited from ON, and what has happened to the suffix in Halling is phonology. So, the sceptic may object, while Herce has presented good arguments for his part of the story, what is presented here may be accidental formal identity, preserved through the centuries simply because morphology can be quite conservative. How can we tell? According to Maiden (Reference Maiden2018:302):

We know for sure that heterogeneous distributional patterns are not synchronic ‘junk’, that they are not mere accidental residues of earlier language states, when they are defended against external morphological changes that would otherwise be expected to disrupt them, or when novel kinds of allomorphy are corraled into those same patterns.

Novel kinds of allomorphy are indeed corraled into the same patterns in the case of inf=(3)prs.pl. A number of verbs have had their infinitives re-shaped. The reasons are in part phonological, in part morphological. Examples include Norwegian kle ‘dress, clothe’, blø ‘bleed’ from ON klæða, blǿða. The ON past tense 3.sg forms were klæddi and blǿddi, respectively; in ON there was a morpho-phonological rule to the effect that ð+ð should yield dd. After the ‘classical’ ON period, the consonant ð is lost in Norwegian (Kristoffersen & Torp Reference Kristoffersen, Arne and Helge2016). The infinitives will then have been klæa, blǿa, with a hiatus of two vowels. There are many examples of such hiatus being ‘rectified’ in the history of ON and later Norwegian, and many where it is not (see Noreen Reference Noreen1923:117). The past tense forms klæddi, blǿddi were reanalysed as klæ+ddi and blǿ+ddi, presumably partly under the influence of such past tense forms as val+di (of velja ‘choose’), ken+di (of kenna ‘know’). Monosyllabic infinitives such as klæ, blǿ, arise; something of an innovation, because ON infinitives are usually bisyllabic. It is important for present purposes that the new ‘short infinitives’ do not arise for purely phonological reasons. At the same time, phonology plays a part, not only in the change ð > Ø, but also because ‘long’ consonant segments in unstressed syllables (e.g. -ddi) typically are shortened (-di). (See Dammel Reference Dammel2011:225–248 for a more thorough discussion.)

Venås (Reference Venås1967:347) emphasises that in Norwegian dialects retaining the present plural, the present plural is (except in one verb, ‘be’) always identical to the infinitive. So also for more recent formations like kle, blø, the infinitive is identical to the present plural; direct inheritance from ON cannot explain this. We do not find *klea, *bløa. It would have been detrimental to my argument if we had found such a form in either the infinitive or the present plural without finding it in both; that we do not. Note that this holds also for the verb Nynorsk lea ‘move’ (ON hliða, liða), which has not been reshaped into a monosyllabic infinitive.Footnote 6 That verb also retained the identity between the infinitive and the present plural.

The same syncretism (inf=prs.pl) was found in the Swedish written standard up to WWII (see Teleman, Hellberg & Andersson Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999:546), also there irrespective of whether the verb was an old one whose infinitive was bisyllabic or a more recent monosyllabic formation.Footnote 7

Sceptics may perhaps wish to suggest a phonological rationale. For example, for the present plural=infinitive in the verb gå ‘go’ in Swedish, they might suggest that a sequence such as /oːa/ is not compatible with the phonology, i.e. that gå contains an underlying final /a/, and so that the formal identity is not so new. Such deletion was the case at one stage, but current Swedish does contain /oːa/ sequences, compare sjåare ‘harbour worker’, blåa ‘blue, pl’.Footnote 8 Even if a (morpho-)phonological analysis had been possible, it would not follow that such an analysis necessarily would be superior to the morphomic one. The burden of proof cannot lie only on one side of the debate (Maiden Reference Maiden2018:21). There is evidence that even where linguists may be tempted to explain away allomorphy by a (morpho-)phonological rule, speakers do not necessarily make this analysis (e.g. Sims-Williams & Enger Reference Sims-Williams and Hans-Olav2021:136).

2.2 Imperative and past tense

For a small set of Norwegian verbs, there is – in some dialects as in the written Bokmål standard – a syncretism between the imperative and the past tense. The set consists of roughly seven verbs, including hogge ‘chop’, sove ‘sleep’, løpe ‘run’, komme ‘come’, låte ‘sound’, gråte ‘weep’, hete ‘be called’. The imperative of hogge is hogg, as in Bare hogg, du! ‘Just you chop!’, and the past tense of the same verb is hogg, as in Kari hogg ned treet ‘Kari chopped down the tree’. It is unusual for verbs in Norwegian to form their past by no change; these seven verbs may be the only ones. The imperative and the past can hardly be grouped together against the present, the infinitive and the supine, for pragmatic reasons. Orders aim to change things; the past cannot be changed.

Again, one may ask how we can tell that speakers have noticed the similarity. The answer is straightforward: Of the ON cognate verbs, only koma ‘come’ could display syncretism between imperative and past tense 3.sg (see Venås Reference Venås1967:197ff.). Thus, the class has shown some (limited) productivity in the past; the reason has to be morphological.Footnote 9

While simple diachronic productivity is not as impressive evidence in favour of a morphomic analysis as some evidence marshalled by Maiden (Reference Maiden2018) for Romance, it is still evidence. An anonymous referee rightly points out that this is not a case where patterns are ‘defended against external morphological changes that would otherwise be expected to disrupt them’; yet, a pattern cannot have been a mere ‘accidental residue’ in a period when it was productive. Diachronic changes go through speakers, so an obvious way to guarantee the ‘psychological plausibility’ of a certain structure is to seek out diachronic changes presupposing that structure (Maiden Reference Maiden, Geert and Jaap2005:136).

2.3 Infinitive and past tense in modal verbs

In Norwegian modal verbs, there have been conflicting tendencies at work. One tendency is uncertainty about or even loss of the infinitive (Venås Reference Venås1974:339–340). The same tendency is familiar from English, where it is stronger (compare the non-existent *to would, *to could). In the grammaticalisation literature, this is dubbed ‘decategorisation’ (e.g. deLancey Reference deLancey, Geert, Christian and Joachim2004:153) or ‘degeneration’ (Lehmann Reference Lehmann2015:141), i.e. loss of grammatical properties normally associated with the class relevant for the ‘source’ lexeme.Footnote 10

The other side of the coin is that modals can get new infinitives, perhaps due to paradigmatic pressure. In some cases, the infinitive is restructured so that its stem becomes identical to that of the past tense. For example, the Norwegian infinitives burde ‘ought to’, måtte ‘must’, cannot be explained without reference to an older past tense form. The respective ON infinitives are very different, compare byrja,Footnote 11 mega. The past tense 3.sg of mega in ON is mátti, so the origin of the modern infinitive måtte follows from this past tense form. The origin of burde is more complicated: Heggstad et al. (Reference Heggstad, Hødnebø and Simensen2008) only list byrjaði as the past 3.sg of ON byrja. Yet the past 3.sg burði and a connected present 3.sg are also attested, ‘post-classically’. Examples come from two charters in East Norway in 1399 and 1366, respectively (Fritzner Reference Fritzner1886:222). Thus, the past is re-shaped (burði), and later ‘copied’ onto the infinitive.

There is no plausible semantic or syntactic feature uniting the infinitive and the past against the present while applying only to certain modals. The syncretism does admittedly not hold for all modals in all Norwegian dialects. Yet in the written Bokmål standard, it holds for måtte, skulle ‘should’, ville ‘would’, kunne ‘could’, burde, i.e. for all and only those verbs that the Norwegian reference grammar lists as modals in Bokmål (Faarlund, Lie & Vannebo Reference Faarlund, Lie and Vannebo1997:526). In ON, this held only for kunna. Since there is no non-modal verb in Bokmål where the syncretism holds, it is hard to believe that this is a coincidence, and Bokmål is not unique in this respect.

2.4 Definite singular of feminines and definite plural of neuters

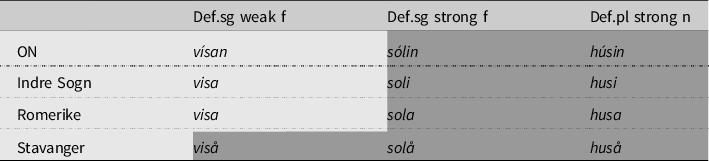

We now turn to an example from the nouns. There are two main classes of ON feminines, traditionally called ‘strong’ and ‘weak’. The former end in a consonant in the indefinite singular, the latter in an -a. Examples of the former include sól ‘sun’, of the latter vísa ‘song’. In the definite singular, the former end in -in, the latter in -an, compare sólin ‘the sun’ vs. vísan ‘the song’.Footnote 12 The ‘strong’ class contains the majority of feminines, the ‘weak’ the minority, but the numerical difference is not large (the strong class constitutes 60% of the feminines in ON according to Beito Reference Beito1954:15, 55% according to Conzett Reference Conzett2007). Neuters such as hús ‘house’, egg ‘egg’, also known as ‘strong’ neuters, took the suffix -in in the definite plural; compare húsin ‘the houses’, eggin ‘the eggs’. See Table 2.

Table 2. Feminines (f) in def.sg and neuter (n) in def.pl in ON and some daughter dialects (rendered in orthography for expository purposes). Shading marks cells sharing a suffix.

As Table 2 shows, strong neuters in the definite plural and strong feminines in the definite singular take the same suffix in ON. It is not obvious that speakers notice this formal identity. The more conservative dialects, such as Indre Sogn, have retained another suffix in the weak feminines than in the strong feminines and the plural of neuters. That certainly does not amount to an argument in favour of morphomes; the pattern in Indre Sogn is expected by regular sound change. The main rule in Norwegian dialects today, exemplified with Romerike in Table 2, is that the definite plural of all neuters takes the same suffix as the definite singular of all feminines (Skjekkeland Reference Skjekkeland2005:102). This does not amount to an argument in favour of a morphomic pattern, either: The change from ON -in to Norwegian -a, the most widespread suffix in the dialects today, is probably due to regular sound change. Thus, ON sólin > Norwegian sola, ON húsin > Norwegian husa and ON eggin > Norwegian egga can all be accounted for phonologically. The majority of dialects that have -a in strong feminines, sola, also have it in weak ones, compare visa (< ON vísan). For present purposes, the question whether the definite sg. of weak feminines, such as visa, is due to sound change or to morphological analogy does not matter; in neither case do we have an argument for morphomes. (If visa is due to sound change, there is no morphology at work; if it is due to analogy, it does not make much sense to label ‘weak + strong feminines’ an unnatural class.)

However, there are dialects where the old definite singular suffix of the weak feminines (vísa) has been extended to the strong feminines (sól) and to the strong neuters (hús). This holds for the dialect of Stavanger (e.g. Berntsen & Larsen 1978 [1924]:210). In that dialect, all feminines end in -å (/o/) in the definite singular, so that ‘the sun’ (strong) has the same suffix as ‘the song’ (weak). The -å (/o/) in the strong feminines and neuters simply cannot come from ON -in by sound change; by contrast, the -å (/o/) in the weak feminines probably has developed from ON -an by sound change. Thus, the suffix in the weak feminines has ousted the suffix in the strong feminines, and then, it has spread to the strong neuters, compare huså (neuter pl).

This diachronic change in the neuters presupposes the reality of the plural suffix syncretism strong neuter – strong feminine. Stavanger is not an isolated case. We find the same formal identity with feminines walking ‘in lockstep’ with the strong neuters in many dialects of south-west Norway (see e.g. Skjekkeland Reference Skjekkeland2005).Footnote 13

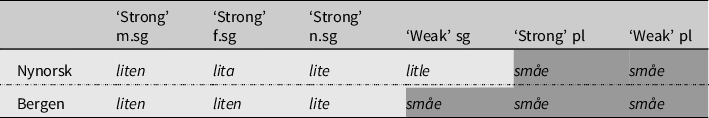

2.5 Definite singular and plural of adjectives

We now turn to the adjectives. A general pattern in Norwegian adjectives is that the ‘weak’ (definite) form singular is formally identical to the plural in the ‘strong’ (indefinite) and weak inflection. In Norwegian Nynorsk, this will look as in Table 3, where the syncretism (shaded) is illustrated with so-called class 1 adjectives, which are perhaps the most type-frequent ones. (To avoid confusion, I have used Arabic numbers for adjective class 1 and, below, Roman numbers for verb class I).

Table 3. ‘Class 1’ adjectives in Nynorsk. Shading marks syncretism.

The formal identity in the three shaded rightmost rows can be accounted for by inherited suffixes and phonological change. Thus, it does not constitute an argument in favour of morphomic patterns. Furthermore, it is possible to come up with a feature that unites the definite singular and the plural against the indefinite singular (even if there are good grounds for preferring a morphomic analysis, see Section 3.1 below).

However, a well-attested case from the Bergen dialect of Norwegian is the over-differentiated adjective liten ‘little, small’, which has behaved differently (Larsen & Stoltz Reference Larsen and Gerhard1912:121–122). In Table 4, it is compared with Norwegian Nynorsk, which illustrates the common pattern in Norwegian. I have kept the ON origin out, for expository reasons (the diachrony of this particular adjective is quite complex).Footnote 14

Table 4. The adjective ‘little’ in ON, Nynorsk and Bergen. Shading marks syncretism.

The diachronic origin of the form småe (/små) ‘little’ has attracted attention and debate (see Maiden Reference Maiden2004, Börjars & Vincent Reference Börjars, Nigel, Alexandra, Glyn and George2011), but not in a way that is immediately relevant. For present purposes, the point is that the suppletive allomorph små(e) has arisen by morphological means, in the plural cells, as in Nynorsk.

In Bergen, however, småe has spread to the definite singular. From a semantic point of view, this redistribution makes little sense. As the Nynorsk column in Table 4 shows, the suppletive plural form småe is a good, clear-cut signal of the plural. Why transfer it to the definite singular? The answer lies in Table 3; the formal identity between the definite singular and the plural was already pervasive in the regular adjectives. This has mattered more than småe signalling the plural clearly. In the Bergen dialect, then, we find an example of ‘morphology overriding semantics’.

3. Theoretical discussion

3.1 Objections relying on features

A number of linguists are sceptical towards the idea of an autonomous morphological level (e.g. Bowern Reference Bowern and Matthew2015, Bermúdez-Otero & Luís Reference Bermúdez-Otero and Ana2016, Embick Reference Embick2016 and Steriade Reference Steriade2016), and many patterns that can be analysed as morphomic can be given alternative analyses. Often, such analyses will be couched in terms of features. Such analyses should not be ruled out a priori, but they cannot be accepted aprioristically, either.

Let us consider the cases from Stavanger and Bergen (see Sections 2.4 and 2.5 above). The Bergen case, where there is a syncretism between definite singular and definite plural of adjectives, may seem easy: The plural can be analysed as marked relative to the singular, and the definite as marked versus the indefinite. So can we simply say that -e is the marked suffix, that the cells are united by being marked relative to the indefinite singular? Such an analysis has some merit, but the snag is that in the indefinite singular, the neuter of class 1 adjectives typically has the suffix -t. Thus, it is too simple just to say that -e is marked, since the neuter is marked relative to masculine + feminine in Norwegian. So perhaps -t is the marked suffix in the strong inflection? Since the suffix -e applies in both strong and weak plural and the entire weak inflection, one might call -e the marked member outside of the indefinite singular. Unfortunately, -e is also the only suffix outside of the indefinite singular. Saying that a certain suffix is the marked option when it is the only suffix in its domain seems too ingenious.Footnote 15

Furthermore, a large class of adjectives (‘class 3 adjectives’), e.g. bra ‘good; acceptable’, has no suffix in any cell in their paradigm, and this class is a truly mixed bag which has to be listed (Sims-Williams & Enger Reference Sims-Williams and Hans-Olav2021), the way inflection classes usually have to. To make the feature-based analysis above work, then, one would have to admit the reality of inflection classes, i.e. of rhizo-morphomic patterns, since the markedness features will have to ‘bite’ for fin, but not for bra. Thus, the only way one can build a case against the morphomic account is, paradoxically, by accepting morphomic patterns, and even then, the feature-based account is not quite convincing (see also Spencer Reference Spencer2019 for a similar conclusion).

We now turn to Stavanger, to the syncretism in suffix between definite singular of feminine nouns and definite plural of neuters. The feminine and the neuter may well be marked relative to the masculine. Still, can we unite the definite singular of feminines and the definite plural of neuters against the rest? In my view, any affirmative answer will be implausible. It will only illustrate a general problem: In the tradition of Jakobsonian Gesamtbedeutungen, features are postulated to capture similarity – sometimes with no (or very little) independent justification. Thus, Carstairs-McCarthy (Reference Carstairs-McCarthy2010:222) observes, with reference to a particular feature-based analysis of Russian that

[i]t is not a surprise if Russian nominal inflectional classes turn out to be describable in this fashion. Rather, in view of the lack of independent support for such features and the consequent freedom with which they can be exploited, it will be a surprise if there is any conceivable inflection-class system that cannot be described in such a way

Even if a semantic feature could unite definite singular of feminines and the definite plural of certain neuters, the feature-based analysis would still be incomplete. The reason is banal: One would then expect this feature to play a role also in other dialects, outside of Stavanger and south-west Norway. Yet the patterns of suffix syncretism vary from dialect to dialect. (In Romerike, for example, the definite plural of masculines and neuters traditionally had the same suffix as the definite singular of the feminines.) By the morphomic approach, the syncretism is just there, a language-particular or dialect-particular fact that need not make any ‘deeper’ sense.

As observed by Maiden (Reference Maiden2018:21),

the burden is on those on both sides of the debate to show that their analysis meets certain standards of plausibility. There are various respects in which the ‘list’ [=morphomic, HOE] analysis can be argued to be more plausible than alternatives that treat morphological phenomena as underlying and as aligned with a single feature.

In short, while it certainly is possible to advance alternative analyses based on features for at least some of the patterns in Section 2 above, such analyses do not look promising. Since ‘morphomic accounts’ in such works as Maiden (Reference Maiden2018), Herce (Reference Herce2020a) and this paper are backed up by different kinds of diachronic evidence, it seems fair to ask for ‘external’ evidence also from feature-based alternatives.

3.2 Taking morphology seriously?

Outside of a context in which morphology is denied (see Section 1 above), it seems unsurprising that morphomic patterns are found (as observed also by Maiden Reference Maiden2018:19). Also Bermúdez-Otero & Luís (Reference Bermúdez-Otero and Ana2016) concede – reluctantly – that there are morphomic patterns. Yet they mention as an alternative the hypothesis of ‘[t]aking morphology seriously: In the absence of evidence to the contrary overt morphological derivation signals lexical semantic derivation’ (Bermúdez-Otero & Luís Reference Blevins2016:321).

To say ‘we are skeptical to the morphomic approach, and our alternative is to take morphology seriously’ is not really to pave the way for a constructive discussion, in my view. Yet the basic problem is that there remain so many examples in morphology where it is hard to believe that identity of form must reflect identity of meaning. For example, it is hard to believe (despite the valiant attempts of Leiss Reference Leiss1997) that there is a common semantic denominator for the English suffixes -s found in present tense (sings), the so-called genitive (Jane’s) and the plural (songs). It is equally implausible to posit a common meaning for the different uses of the East Norwegian suffix -a. They include the definite singular of feminines, the definite plural of neuters, the definite plural of masculines, the past tense of the largest class of weak verbs, and the infinitive of certain verbs.Footnote 16 See Beard (Reference Beard1995) and Trosterud (Reference Trosterud2006) for further discussion.

Another serious problem is that formal (morphological) differences do not always (as Herce Reference Herce2020a:356 observes) correspond to differences in morphosyntactic values, as shown clearly by the phenomenon of over-abundance (for which see especially Thornton Reference Thornton2011, Reference Thornton2012).

‘Taking morphology seriously’ appears to be a slogan for denying that morphology has any autonomy. One wonders what a programme of ‘taking syntax seriously’ would look like.Footnote 17 Presumably, any syntactic regularity would have to be 100% motivated by semantics or pragmatics. While many syntactic regularities are indeed partly motivated by semantics or pragmatics, no serious syntactician would claim that all syntactic regularities are completely motivated in such a way. Esher (Reference Esher2014:334) puts this point nicely:

[T]he presence of a functional correlate or motivation in some morphological mappings does not constitute grounds for assuming that these mappings do not involve the morphomic level; just as the existence of interface phenomena between phonology and syntax does not compromise the existence or autonomy of either component of the grammar.

This underlines the conclusion in Section 3.1 above; merely pointing to a possible feature does not invalidate a morphomic account.

Furthermore, linguists who in general emphasise motivation for grammar are not necessarily bothered by the arbitrariness of distributional classes; for example, Langacker (Reference Langacker1987:422) simply acknowledges their existence and remains completely unfazed. A range of functionalists studying language acquisition, from Bates & MacWhinney (Reference Bates, Brian, Brian and Elizabeth1989) to Ragnhildstveit (Reference Ragnhildstveit2017), emphasise that learning a language is not only about learning form-function relations, but also about learning form–form-relations. The idea behind ‘taking morphology seriously’ seems to be that any morphological similarity has to reflect some deep underlying ‘function’, i.e. a syntactic or semantic commonality. This particular version of functionalism is so extreme that most functionalists would reject it out of hand. It is unexpected, then, that a number of (but far from all) generative linguists rally behind the idea. The aprioristic assumption that there has to be a syntactic/semantic rationale behind a formal (e.g. putatively morphomic) pattern seems unwarranted, psycholinguistically. There is ample evidence that infants are excellent pattern learners (Section 3.3). There is also evidence that, at least in some cases, children rely heavily on formal (phonological) cues in language acquisition, even when semantic cues are available (Culbertson et al. Reference Culbertson, Jarvinen, Haggarty and Smith2019).

Morphomic phenomena may perhaps be compared to the crazy rules of phonology; not in the sense that they are identical, but that both appear pointless and indicate a certain autonomy for the module in question – and that many of the morphomic patterns arise in similar ways, i.e. by reanalysis of phonetically motivated alternations. It is hardly news that there is such a thing as ‘unnatural’ phonology. Therefore, it is far from obvious that there could not be unnatural morphology.Footnote 18

3.3 No theoretical interest?

Another argument sometimes raised against the morphomic approach is that it is without theoretical interest; Embick (Reference Embick2016:299) dismisses the morphomic program as a ‘mere enumeration of facts’ and hence theoretically uninteresting. This argument is highly problematic (see also Maiden Reference Maiden2018:18).

Embick’s argument presupposes general, pre-theoretical agreement over what counts as theoretically interesting. This is hardly the case, and there cannot be any rejection in the absence of an alternative proposal; in the words of Lakatos (Reference Lakatos1968:163); ‘There must be no elimination without the acceptance of a better theory’ (italics original).Footnote 19 Embick is a prominent exponent of the Distributed Morphology (DM) program (e.g. Embick & Noyer Reference Embick, Rolf, Gillian and Charles2007), so a reasonable reading is that DM is the implicit alternative. Therefore, it seems relevant that Spencer (Reference Spencer2019:255) calls this alternative a ‘vacuous and largely discredited exercise, and not an enterprise to be taken seriously’. Clearly, an extensive discussion of DM is beyond the scope of this paper. Yet it is striking that on the one hand, we are told that morphology can be reduced to syntax (e.g. Embick & Noyer Reference Embick, Rolf, Gillian and Charles2007, Siddiqi Reference Siddiqi2019), on the other, when examples are presented of morphomic patterns, i.e. of ‘pure morphology’ (Section 1) that cannot be reduced to syntax, these examples are dismissed as ‘mere enumeration of facts’. This argument seems self-contradictory.

On a more positive note, an approach to morphology can be theoretically interesting in several ways. The morphomic approach is interesting in showing the relative autonomy from syntax (Section 1), but there is also an interesting convergence with psycholinguistics. Morphomic patterns may seem useless, but the ‘human mind is an inveterate pattern-seeker’ (Blevins & Blevins Reference Blevins and Blevins2009a:1), noticing patterns even when there is little reason to do so. Speakers are probably scanning for regularities in the mental lexico-grammar constantly, whether this exercise is useful or not (Bybee & Beckner Reference Bybee, Beckner, Bernd and Heiko2009:830).

Given recent psycholinguistic research on statistical learning, morphomic patterns are to be expected. Arciuli & Torkildsen (Reference Arciuli and Janne2012:1) report that ‘[a] now substantial body of research suggests that language acquisition is underpinned by a child’s capacity for statistical learning (SL)’. According to Arciuli & Torkildsen (Reference Arciuli and Janne2012:7),

many infants, children, adolescents, and adults are equipped with highly efficient abilities to detect statistical regularities in input. Recent research has brought the knowledge that humans use the output from these statistical mechanisms in language acquisition.

Arciuli et al. (Reference Arciuli, von Koss Torkildsen, Stevens and Simpson2014:1) also say that ‘Statistical learning (SL) studies have shown that participants are able to extract regularities in input they are exposed to without any instruction to do so’.

Morphomic patterns involve a distributional regularity in the input (Maiden Reference Maiden, Geert and Jaap2005:137). Perhaps part of the scepticism against morphomic patterns is grounded here. ‘Distribution’ may sound old-fashioned. As Herce (Reference Herce2020a:75 footnote Footnote 11) puts it,

[a] morphome is … basically a list: a list of lexemes (in the case of inflection classes) or morphosyntactic contexts (in the case of metamorphomes) that only belong together because they share (some) inflectional properties.

Lists may sound boring, but it is important not to let our sense of esthetics block our appreciation of facts.Footnote 20 Given the recent evidence on statistical learning, the old-fashioned connotations of ‘distribution’ is a pseudo-problem. As for the alleged ‘uselessness’ of morphomic patterns, if humans cannot help themselves in noticing patterns, the issue of usefulness is neither here nor there.Footnote 21

3.4 An excursus on segmentation

In Section 2.1 above, a problem of segmentation was glossed over. By traditional analyses for Faroese and Swedish (see Höskuldur Thráinsson et al. Reference Höskuldur, Petersen, Lón Jacobsen and Hansen2012:136 and Teleman et al. Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999:518–519, respectively) and Icelandic, the second a in the infinitive of class I verbs (the largest verb class) like kasta, kalla is part of the stem, while for other verbs, the second a is a suffix. The reason is that a is found also in the imperative of class I verbs, and this is different for the imperative of members of other classes. The traditional analysis thus implies that speakers of Faroese do not note that both e.g. nevna ‘mention’ and kalla ‘call’ end in a, since only in the former verb is the a a suffix, whereas they do note that both nevna and bíta ‘bite’ do, since in these two, a qualifies as a genuine suffix. Mutatis mutandis, the same holds for Swedish. By this analysis, the obvious generalisation that all infinitives (except the monosyllabic ones) end in a is simply lost. Therefore, it has been suggested that class I verbs also have a suffix -a; the a is not part of the stem in any infinitive (see Enger Reference Enger2016:20–21 and references therein). By this more recent analysis, the imperative of class I verbs emerges as formed in a different way than that of others, compare Swedish kalla! ‘call!’ vs. bit! ‘bite!’, whereas the older analysis saw them as formed by one operation (‘the imperative is identical to the stem’). The more recent segmentation may nevertheless be preferable to the older one, but Blevins, Ackerman & Malouf (Reference Blevins, Farrell and Robert2019:277) make a relevant point:

[T]he separation of stems from exponents raises recalcitrant problems in many languages. … From a WP perspective, this type of challenge is an artefact of a flawed method of analysis. … from the standpoint of an implicational WP model, it is unsurprising that different, and possibly overlapping, sequences may be of value in predicting different patterns.Footnote 22

Therefore, Blevins et al. argue in favour of a ‘gestalt-based conception of word structure’. That is an attractive idea (compare also, for example, Bybee & Moder Reference Bybee and Carol Lynn1983, Bybee Reference Bybee2001, Nesset Reference Nesset2008 and Kapatsinski Reference Kapatsinski2012 on ‘product-oriented generalisations’).Footnote 23

4. Conclusions

This paper has presented five different meta-morphomes in North Germanic, involving verbs, nouns and adjectives, i.e. the major word classes (Section 2). The list is not meant to be exhaustive, but it has presented some reasonably clear examples. There is diachronic evidence in favour of the patterns described here (Section 2), in terms of diachronic productivity, and this constitutes independent motivation for them being somehow ‘real’ to speakers.

Morphomic patterns have been met with scepticism in the literature, but at least some of the scepticism is not well founded. It is, of course, legitimate to advance alternative non-morphomic analyses, but rejections based only on the argument that a certain feature can be postulated instead is insufficient (Section 3). As Maiden (Reference Maiden2018:18–21) argues, the onus of proof cannot be only on linguists arguing in favour of a morphomic account. It must lie equally on ‘those who propose to account for putative morphomic phenomena in ‘non-morphomic’ terms’; they need ‘not only to show that the mechanisms they propose are possible, but that they are otherwise needed and independently motivated in the grammatical systems of the languages in question’.

Acknowledgments

For generosity and encouragement, both when commenting on an early draft of this paper and in general, my sincere thanks to Martin Maiden, to whom this paper is dedicated on the occasion of his 65th birthday. Thanks are also due to three NJL referees, whose comments have been very helpful.