1. Introduction

The Finnish language is notable for its extensive use of non-finite constructions rather than subordinate clauses. This preference for non-finite verb forms is generally considered an original typological feature of Uralic languages (Hakulinen Reference Hakulinen1968:462, Ikola Reference Ikola1974:7, Häkkinen Reference Häkkinen1985:124, Lehtinen Reference Lehtinen2007:58). However, the development of Finnish non-finite structures into their present form has been influenced by other European and classical languages (Häkkinen Reference Häkkinen1994:477). In Estonian, the participle structures corresponding to Finnish referative constructions evolved into the Modus Obliquus, a construction used to express not only reported speech but also evidentiality. This development likely resulted from the convergence of two originally Estonian structures and the influence of foreign languages (Campbell Reference Campbell, Closs Traugott and Heine1991).

This paperFootnote 1 examines the diachronic development of the use and frequency of Finnish referative constructions (RCs, also known as participle constructions), which are used to express reported discourse, perception, and cognition. These structures are considered the Finnish equivalent of the Latin Accusativus cum Infinito construction (ACI) (Ikola Reference Ikola1960:63, Forsman Svensson Reference Forsman Svensson1983:5). The ACI construction, where the semantic subject of an infinitive verb form utilises the accusative case, is employed in both Latin and Greek, and the construction is used to express indirect discourse following verbs of saying, thinking, knowing, and perceiving (Ayer Reference Ayer2014:§577). The ACI construction has been borrowed by other languages through translation (Fischer Reference Fischer1992), and it is likely that the features of RCs in Old Literary Finnish – such as their preference to occur with certain matrix verbs – were influenced by Latin. This article, however, focuses on the changes in Finnish regarding this structure. The influence of Latin on Finnish RCs will be examined in a separate study.

Our data come from six Finnish translations of the New Testament, spanning from 1548 to 2020. Expectations for biblical language are controversial: while accessibility is desired, translations strive to be as exact as possible. Additionally, dignified and prestigious language is valued, although it may not always align with accessibility and understandability. Regarding non-finite clauses, modern Finnish language guidelines caution against their use due to their potential to condense information into an unhelpfully concise form (Kielitoimiston ohjepankki). In the context of Easy Finnish,Footnote 2 non-finite clauses are considered difficult constructions and should be avoided (Selkokeskus). Over centuries, not only has the language evolved, but so too have translation traditions and perceptions of what constitutes good and accessible standard language.

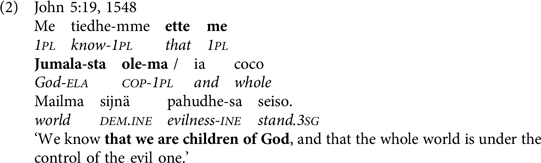

We track the frequency of Finnish RCs from the sixteenth century to the present day. We focus on the variants of RCs (example 1), comparing them to subordinate clauses beginning with the conjunction että (‘that’, example 2), which are used in similar contexts to RCs. The following examples are drawn from the first Finnish translation of the New Testament (1548). All English translations of Bible verses given in examples are from the New International Version of the Bible (NIV 2011).Footnote 3

Similar to the Latin ACI construction, typical Finnish RCs are generally preceded by verbs of communication, cognition, or sensory perception (e.g. nähdä ‘to see’, tietää ‘to know’ in the examples above). Finnish RCs exhibit a form of switch-reference marking, distinguishing between constructions with the same semantic subject as the matrix clause (SS) and those with a different subject (DS). Section 3 introduces the details and variations of Finnish RCs.

As previously noted, most of the earliest written Finnish texts are translations of the Bible and other spiritual texts. The original language of the New Testament was Greek, but the translator of the first Finnish version also utilised Swedish, German, and Latin texts as sources. The influence of these languages is evident in both the lexicon and the appearance of foreign constructions (Itkonen-Kaila Reference Itkonen-Kaila1997:10, Merimaa Reference Merimaa2007:103, Salmi Reference Salmi2010:19). Syntactic features can be transferred from one language to another through translation, which is referred to as syntactic borrowing. Syntactic borrowing often results from several factors and is not easily proved (Fischer Reference Fischer1992:17). The translation of the Bible is characterised by a high degree of verbal accuracy, meaning that in all source languages the structures can be similar to each other (Itkonen-Kaila Reference Itkonen-Kaila1997:64). Itkonen-Kaila (Reference Itkonen-Kaila1997:17–19), who compared parts of the 1548 New Testament to the source texts, noted that verses are often influenced by several languages rather than being directly translated from a single source. For instance, Finnish verb structures such as the temporal construction have been found to be influenced by Latin (Lindén Reference Lindén1966:1–8), and Itkonen-Kaila (Reference Itkonen-Kaila1997:68) suggested that the negation sometimes found in Old Literary Finnish RCs (see Section 3.2) may be directly influenced by Greek.

Further research could involve comparing more recent translations with the source texts to determine whether Finnish RCs have diverged from their original models over time. This paper contributes to the examination of variations between RCs and subordinate clauses in Finnish, while a systematic comparison with source constructions is left for a future study.

We aim to answer the following research questions.

-

1. How has the distribution of RCs and että clauses changed throughout the development of written Finnish? Has the switch-reference marking of RCs affected this variation?

-

2. Do certain matrix verbs exhibit a preference for specific constructions? Has the set of verbs changed during the development of written Finnish?

To investigate these developments, we collected all RCs (N = 263) and subordinate että clauses (N = 663) used in reporting discourse, perception, and cognition from the earliest Finnish translation of the New Testament (1548). We then compared the collected Bible verses to their counterparts in six subsequent editions from 1642, 1776, 1938, 1992, and 2020 (see Sections 2 and 4).

Forsman Svensson (Reference Forsman Svensson1983, Reference Forsman Svensson1986) studied RCs in seventeenth-century Finnish. Her material included religious literature, such as the 1685 Bible, and legal texts (Forsman Svensson Reference Forsman Svensson1983:87). She compared the seventeenth-century material with mid-twentieth-century prose but did not track changes in the frequency of RCs over time. Instead, she identified differences between authors and parts of the Bible (Forsman Svensson Reference Forsman Svensson1983:122–130). The frequency of RCs appears to be influenced by the genre, topic, and syntax of texts. Forsman Svensson (Reference Forsman Svensson1986) demonstrated that most RCs in her data occurred within subordinate clauses, thereby avoiding multiple consecutive subordinate clauses. Our research complements Forsman Svensson’s work by covering a broader time span from 1548 to 2020 and using multiple versions of the New Testament. RCs in sixteenth-century Finnish and nineteenth-century newspapers have also been addressed in two master’s theses (Sjöblom Reference Sjöblom1991, Kurki Reference Kurki2018). Other studies have examined Old Literary Finnish verb structures, their development, and the role of language contact in this process (e.g. De Smit Reference De Smit2006, Pekkarinen Reference Pekkarinen2011, Elsayed Reference Elsayed2017). However, these studies have not examined RCs or their alternatives.

We approach these constructions from a usage-based and functional perspective. The development of electronic corpora facilitates our quantitative and diachronic analysis, enabling us to explore large-scale trends in how the frequency of RCs has varied across different translations and with which verbs they occur.

The following section introduces the editions of the New Testament that were examined for our data. Section 3.1 takes a closer look at the RCs and rules regulating the constructions. Variants of the constructions in Old Literary Finnish will be examined in Section 3.2. Section 4 introduces the methods used for gathering and analysing the data. A quantitative analysis of the constructions under study is provided in Section 5, divided into several subsections. Finally, the conclusions drawn from our findings are discussed in Section 6.

2. Finnish translations of the Bible from 1548 to 2020

In the sixteenth century, the Catholic Church split into Protestant movements, and Finland, as part of Sweden, adopted Lutheranism (see Nummila Reference Nummila, Mikko Kauko, Nummila, Toropainen and Fonsén2019). The Lutheran tradition encouraged the use of vernacular languages in religious teaching, which motivated the first Finnish translation of the New Testament (1548). Before this, the Finnish language was rarely written (Mielikäinen Reference Mielikäinen2014:29). Some translations of prayers had been written down during the Middle Ages, and a few manuscripts containing texts needed for services have survived from the sixteenth century (Häkkinen Reference Häkkinen2016). There may be traces in Agricola’s orthography indicating some earlier partial Bible translations. Additionally, some legal texts may have been written in Finnish even before the first printed New Testament (Koivusalo Reference Koivusalo1984). Agricola published an ABC book (Abckiria, 1543) and a prayer book (Rucouskiria, 1544) before his New Testament translation, but the 1548 edition was the first major work printed in Finnish. Thus, it arguably had more impact on creating a shared standard for written Finnish than any other single book (Ikola Reference Ikola1992:51).

Translating the Bible is a challenging task. The source text is exceptionally old and far from the Finnish cultural context, and the choice of wording must consider theological interpretations as well as the stylistic and emotional values of the text. Until the twentieth century, a key strategy for translating the Bible was formal equivalence, meaning that the translation sought to preserve the grammatical structures of the source text rather than focusing on conveying the message and making the best use of the target language’s structures (Glassman Reference Glassman1981:48). However, since Luther’s time, readability and understandability in the language of the Bible have been considered important (Nummila Reference Nummila, Mikko Kauko, Nummila, Toropainen and Fonsén2019:21). As the standards of the target language and translation ideologies have evolved, new translations have become necessary. Therefore, Bible translations provide a unique resource for examining the changes in standardised literary language.

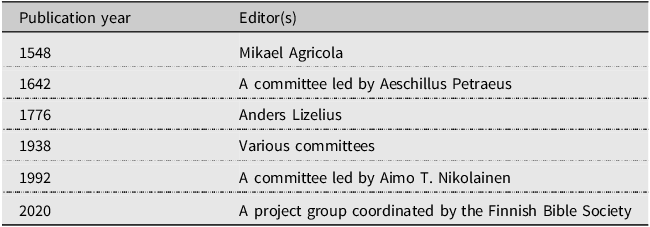

Our data cover six Finnish translations of the New Testament, as listed in Table 1. The New Testament was first translated by Mikael Agricola during the reformation in the early 1500s. According to his declaration, Agricola’s language represents the dialect of Turku, the capital of Finland at the time, but he seems to have aimed for a widely understandable form of language. In the foreword of his translation of the New Testament, Agricola lists Greek, Latin, German, and Swedish editions as sources for his work (Itkonen-Kaila Reference Itkonen-Kaila1997:10). The linguistic influence of Swedish has been noted in many studies. In addition to using the Swedish-language Bible as an important source, Agricola himself was bilingual (Häkkinen Reference Häkkinen2015:31–33).

Table 1. Finnish editions of the Bible/New Testament used for data

The first complete Finnish translation of the Bible was published in 1642, almost a hundred years after its predecessor in 1548. The 1642 translation was based on Agricola’s work and drafts prepared by a translation committee established in 1602. Evidence suggests that bishop Ericus Erici Sorolainen used new translations of at least part of the Old Testament when he wrote his collection of sermons, published in 1621 and 1625 (Puukko Reference Puukko1946:7, 123–128; Rapola Reference Rapola1942, Reference Rapola1963:11; Kiuru Reference Kiuru1991, Reference Kiuru1993). The committee responsible for the 1642 edition was instructed to follow the original Greek and Hebrew texts and to consult the German Lutherbibel (1545). However, the translation shows significant Swedish influence (Ikola Reference Ikola1992:52), with the Latin edition also serving as an important source for the translators (Puukko Reference Puukko1946:130). A language editor on the committee reviewed the Finnish wording, making adjustments such as removing negative participle structures and prefix verbs and changing subordinate clauses to non-finite forms (Häkkinen Reference Häkkinen1994:495–496).

The 1776 edition was the first corrected translation of the entire Bible from 1642, although the 1642 edition had undergone linguistic renewal in 1683–1685. The 1776 edition remained in use for more than 160 years, canonising the biblical style. By the mid-1800s, standardised Finnish was rapidly developing, and the language no longer matched that used in the Bible. In 1851, the Bible Society of Finland published a revised edition with notes (Kolehmainen Reference Kolehmainen2014a). A new translation was proposed by A. W. Ingman in 1859, but it was criticised for being too modern and unconventional (Mielikäinen Reference Mielikäinen2014:36–37).

Efforts to produce a new, linguistically up-to-date edition spanned over multiple decades, with work carried out by various committees without reaching a commonly agreed conclusion. The final version of the new translation was published in two stages: the Old Testament in 1933 and the New Testament in 1938.Footnote 4 This edition of the Bible was the first Finnish translation to involve professional linguistic inspectors in the translation process. The authors, poets, and linguists involved were eager to preserve the solemn style of the earlier version, which is why the language of the translation was already old-fashioned when it was published (Nuorteva Reference Nuorteva1992:32; Kolehmainen Reference Kolehmainen2014a:70, 79–83; Kolehmainen Reference Kolehmainen2014b; Mielikäinen Reference Mielikäinen2014:79–85). Researchers have noted the extensive use of non-finite structures in the 1938 translation (Ikola et al. Reference Ikola, Palomäki and Koitto1989, Mielikäinen Reference Mielikäinen2014:38).

By the 1970s, the need for a new translation had become evident once again. The formal translation tradition gave way to more functional and dynamic approaches (Suihkonen Reference Suihkonen1998:82). The discovery of new texts, particularly the Qumran manuscripts found between 1947 and 1952, which were about 1,000 years older than previously known manuscripts, further supported the need for an updated translation (Sollamo Reference Sollamon.d.). A translation committee for the 1992 edition was established in 1973, with linguistic objectives that included ‘clear, natural, and contemporary standardized language’ (RKK 1975:20).

The 1992 translation remains the latest translation approved by Finland’s largest religious body, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland. However, the text does not fully meet the needs of all users, and several new translations of the Bible have been published in the twenty-first century. To explore the future direction of Bible translation into Finnish, we also examined the most recent translation of the New Testament from 2020 (Uusi Testamentti 2020 – Raamattu mobiilikäyttäjille). This electronic translation, published by the Finnish Bible Society in 2020 in cooperation with the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland on an ecumenical basis, is aimed at mobile device users. The translation ‘takes into account the ability of 20-year-olds to understand Finnish’ and is also available as an audio book (Raamattu.fi). These factors likely contribute to the simplicity of the language structures used. However, the editors clarify that the 2020 translation is not written in Easy Finnish but aims for ‘rich but fluent Finnish that is easy to read’.

3. The Finnish referative construction

3.1 Definition of the construction

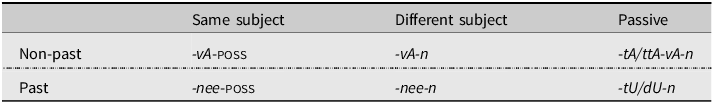

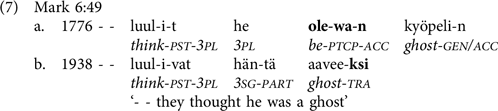

The Finnish RC is a non-finite clause construction that generally consists of a participle verb form combined with a marking that expresses the semantic subject of the participle. The semantic subject is marked either by a noun or pronoun phrase as a genitive attribute of the participle (when the semantic subject differs from that of the matrix clause, DS) or by a possessive suffix added to the verb form (same subject, SS). The construction broadly corresponds to a subordinate että (‘that’) clause. It also has some clause-like properties, such as the distinction between past and non-past tenses and the use of a passive form. The morphological variants of the participle endings used in the Finnish RC are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. The morphological variants of participle used in the RC (VISK:§538)

As shown, the semantic subject of the RC is marked with a possessive suffix when it is coreferential with the matrix verb (example 4 below). When the subject is not shared, it is expressed with a genitive noun or pronoun phrase (example 3). The passive marker -tA or -ttA- (the form depends on the stem, consonant gradation and vowel harmony) may occur before the participle ending. In the past passive form, the passive and participle markers fuse into the affix -tU/dU- (VISK:§110).

Historically, the case of the different subject noun phrases was accusative, and the final n-marking in the participle endings shown in Table 2 was originally an accusative case marking. Due to historical phonological changes, the singular marking of the accusative case changed from -m to -n, making it coincide with the genitive case. The history and development of the semantic subject case marking in the RC has been studied by Forsman Svensson (Reference Forsman Svensson1983) and Ikola (Reference Ikola1960). In this paper we focus on diachronic changes in the frequency of the structure and its matrix verbs and do not systematically consider the case marking of the phrase expressing the semantic subject.

Following phonological changes, the case of the subject phrase was reanalysed as genitive, and the participle endings are now understood as fixed units (VISK:§538). The historical accusative ending -m was not used in the plural; instead, a nominative form was used. However, through analogy, in the RC, the genitive case was applied to plural occurrences as well (Itkonen Reference Itkonen1966:330; see also Penttilä Reference Penttilä1963:632, Forsman Svensson Reference Forsman Svensson1983:5). The history of the structure can be seen in Old Literary Finnish (see Section 3.2), where the plural nominative–accusative form is sometimes used instead of the genitive (Ojansuu Reference Ojansuu1909:145, Forsman Svensson Reference Forsman Svensson1983:5–6).

We gloss the participle endings as ptcp, separating the former accusative ending -n, and the case of the noun phrase expressing the RC subject as gen/acc. In the plural, we gloss the noun phrase case as gen.

The alternation between a noun phrase and a possessive suffix in marking the semantic subject of the RC, which can be understood as a type of switch-reference system (for switch-reference in general, see e.g. van Gijn & Hammond Reference van Gijn and Hammond2016), was already well established in Old Literary Finnish and has remained similar to modern times (see Section 3.2). In modern Standard Finnish, the RC does not have negation or other moods beyond indicative (VISK:§538). However, in Old Literary Finnish, negated RCs were sometimes used (see Section 3.2).

Three subtypes of RCs can be distinguished. The first type, which most indisputably corresponds to an että clause and is the most typical form of the RC in written Finnish, functions as an object for a transitive verb (see examples 3 and 4).

The second type occurs with an intransitive sensory perception verb. In this type, the matrix predicate is congruent with the construct’s subject (see example 5). Therefore, constructions of this type involve, for example, evidence based on visual or auditory perception. RCs of the second type more closely resemble the Estonian structure from which Modus Obliquus evolved (Campbell Reference Campbell, Closs Traugott and Heine1991:287).

In spoken Finnish dialects, the distribution of the first and second types of RCs is more balanced than in the written texts. In the Finnish Dialect Corpus of the Syntax Archive, 59.4% of the RCs represent the first type. In written genres, the first type is more clearly dominant, with only about 20% of the RCs representing the second type (Ikola et al. Reference Ikola, Palomäki and Koitto1989:469). In modern conversational data, the frequencies are even: half of the RC occurrences (17/34) found in an annotated corpus of Finnish everyday conversation (ArkiSyn) represent the second type, with most of these (15/17) featuring the verb näyttää (‘to seem’) as the matrix verb. This suggests that in conversational speech, the structure tends to be somewhat fixed, which aligns with the general characteristics of spoken language syntax (Hakulinen & Leino Reference Hakulinen and Leino1987:42). Since RCs are particularly common in narratives, variations in spoken datasets are likely to occur, for example, between conversations and interviews.

Interestingly, in our searches on the 1548 New Testament, only two occurrences of the second type of RCs were found, both accompanying the verb näyttää. It seems that in the oldest translation, another structure – one not reached by our corpus search – was used to convey similar meanings to those of the RC with intransitive perception verbs found in dialects and later texts. Thus, our analysis focuses on the first type of RC.

The construction can also act as a subject for intransitive verbs that can attract an että clause as a subject (e.g. ilmetä ‘to appear, to turn out’ or paljastua ‘to be revealed’). It has been suggested that the subject-acting construction is the newest addition among RC types, and it is rarely used even in modern Finnish (Ikola et al. Reference Ikola, Palomäki and Koitto1989:467). Since this type does not occur within our data, it will not be discussed in further detail here.

There are differences between spoken and written language and between different text genres in terms of the proportion of RCs sharing a subject with the matrix clause. According to Forsman Svensson (Reference Forsman Svensson1983:175), in biblical language the majority of RCs have a different subject, while in legal language the distribution is more even. The distribution of SS and DS occurrences has not been examined in the Finnish Dialect Corpus. However, our search in the ArkiSyn corpus suggests that modern conversational speech may prefer RCs with coreferential subjects. Although only 17 occurrences of the first type of RCs were found, 12 of them share a semantic subject with the matrix clause. Given the infrequency of the structure in the corpus, more data are needed for firm conclusions, which will be left for future studies. The matrix verbs of the first type of RCs are more varied in conversations than those of the second type.

Our data, consisting of different versions of the same text, allow us to examine possible changes in RC usage, particularly in terms of shared and different subjects, regardless of the text topics. Comparison of our findings with other genres will be reserved for future studies.

3.2 Referative constructions in Old Literary Finnish compared to the modern standard

In this section we explore the changes that RCs have undergone during the development of the Finnish written language, drawing on previous research, and how the guidelines concerning them in standard language manuals and grammar books have been established. The status of participle forms in grammar guides has been discussed in more detail by Forsman Svensson (Reference Forsman Svensson1983:12–23).

In Old Literary Finnish, the RCs were still developing, and previous research noted that forms deviate from the modern standard. The reanalysis of the construction – where the NP began to be understood as the subject of the non-finite verb form rather than the object of the matrix clause – was still ongoing. Plural forms, in particular, included NPs in the nominative–accusative case. When the NP was still interpreted as the object of the matrix verb, the structure more closely resembled the Latin ACI structure (Forsman Svensson Reference Forsman Svensson1983:5).

The structure also exhibited other variations. Negative RCs were sometimes used, whereas today the construction lacks a true negative form. Negation can now only be expressed in the matrix clause, which can cause ambiguity in certain cases (Ikola Reference Ikola1960:65, Hakulinen Reference Hakulinen1968:465–466). Negation is thus presented as one of the factors that favour the use of a subordinate clause instead of an RC (Forsman Svensson Reference Forsman Svensson1983:94). Of the 663 että clauses collected from the 1548 New Testament, 97 are negated (14.6%). Negation can affect the frequency of matrix verbs: e.g. verbs tietää ‘to know’ (15 occurrences) and sanoa ‘to say’ (11 occurrences) are also used with negated että clauses (see Section 5.3). In later editions, the number of negative että clauses decreases to the 50 occurrences (7.5%) of the 2020 edition, suggesting a preference for simpler expressions. Negative RCs are found in the three earliest editions (1548, 1642, 1776; eight occurrences altogether). In other Old Literary Finnish texts, negative RCs were found up until the nineteenth century (Häkkinen Reference Häkkinen1994:402, 477).

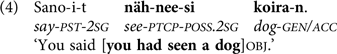

In Old Literary Finnish, another participle construction was used in functions similar to RCs. In this construction, a participle was marked with a translative case instead of an accusative (example 6).

Forsman Svensson (Reference Forsman Svensson1983) thoroughly examined the seventeenth-century translative construction, comparing it to RCs. Although we did not include the translative construction in our data search, a considerable number of RCs in the 1642 edition were changed to this construction (see Section 5.1). According to Ikola (Reference Ikola1960:96), the use of the translative case in referential contexts was typical of old spoken Finnish and was found in old dialects and other Finnic languages. It is said to be a feature of early written Finnish (e.g. Siro Reference Siro1964:145). In contrast to the modern RC, in structures expressing reported speech using the translative case, the NP corresponding to the subject of the RC is still interpreted as the object of the matrix verb (Forsman Svensson Reference Forsman Svensson1983:6). In Old Literary Finnish, there was no clear distinction between the functions of RCs and translative constructions (Forsman Svensson Reference Forsman Svensson1983:8–9), and grammar manuals presented the forms as alternatives (e.g. Wikström Reference Wikström1832:56).

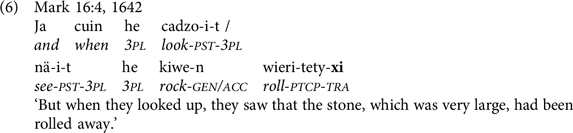

During the twentieth century, the functions of the translative construction became distinct from RCs and now it is mainly used with some non-factive cognitive verbs (Forsman Svensson Reference Forsman Svensson1983:291). Example 7 shows how the RC occurring with the verb luulla (‘to think, to assume’) in the 1776 Bible was reformulated as an NP in the translative case in the 1938 translation. In more recent translations in our data, a constituent in the translative case in such constructions is usually a noun or adjective phrase instead of a participle verb form.

The first Finnish language guidebooks were published in the seventeenth century to teach Finnish to civil servants and foreigners who knew Latin (Vihonen Reference Vihonen1978:39–40, Häkkinen Reference Häkkinen1994:28). The seventeenth- and eighteenth-century grammar books (Petraeus Reference Petraeus1649, Martinius Reference Martinius1689, Vhael Reference Vhael1733) do not contain rules or examples of RCs. In the nineteenth century, some books describe RCs, but the descriptions are scarce, incomplete, and scattered throughout the books (Forsman Svensson Reference Forsman Svensson1983:12–23). Examples of variations not found in our materials are sometimes given (e.g. Judén Reference Judén1818:49). The correspondence with the Latin ACI construction is mentioned in some books as late as the early twentieth century (Forsman Svensson Reference Forsman Svensson1983:32).

The rule for semantic subject marking alternation between a genitive noun phrase and a possessive suffix is spelled out in Koriander’s (Reference Koriander1859:7) grammar book. However, as mentioned earlier, the system of marking switch-reference was relatively consistent already in the 1548 translation: only 13 exceptions (out of 98 SS RC occurrences) were found where a shared semantic subject is marked by a third-person pronoun used as a reflexive pronoun and accompanied by a possessive suffix, resulting in forms like häne-ns (3sg-poss.3sg) or similar forms in other persons. By the eighteenth century, these occurrences were replaced by the reflexive pronoun itse (‘self’), and in the twentieth-century translations, by possessive suffixes. Our data include no exceptions in the other direction, where a DS RC would be marked by a possessive suffix. However, some grammar books present such examples (e.g. Setälä Reference Setälä1880:46).

In the twentieth century, the description of the RC becomes clearer in grammar guides (see e.g. Saarimaa Reference Saarimaa1930:87, Reference Saarimaa1967:194–195). Today, as mentioned in the introduction, grammar guides caution against the use of participle structures, which are considered prone to errors and can make the text difficult to read. Some inconsistencies in RCs persist, particularly in the case marking of the object in passive forms and the semantic subject case marking in existential occurrences (Häkkinen Reference Häkkinen1994:403; see also Hakulinen Reference Hakulinen1968:466). However, since passive and existential occurrences are marginal in our data and not the focus of our study, these variations are not presented here.

4. Materials and methods

Our materials encompass six Finnish translations of the New Testament, ranging from the oldest one to the most recent: 1548, 1642, 1776, 1938, 1992, and 2020. All of the examined translations are available online. To collect the data, we used the morphosyntactically annotated corpus of the oldest Finnish translation of the New Testament, Se Wsi Testamenti from 1548. This corpus is freely available through the Korp user interface. All of Agricola’s written works are accessible as annotated corpora at the Language Bank of Finland. To access the later translations, we used three websites that allow for easy browsing and comparison of Finnish Bible translations across different periods.

We began by searching the 1548 New Testament corpus for RCs, using the concordance programme through the Korp user interface. To obtain the most accurate results with minimal unrelated hits, we employed the advanced search mode. The search term specified that the morphological analysis must include a participle form of a verb. This query returned a total of 5,394 hits, from which we manually collected all occurrences of RCs (N = 264). To compare RCs with että clauses, we searched the lemma että to capture all spellings of the conjunction. This search yielded 3,002 hits, which, after manual scanning, resulted in 583 subordinate clauses with a matrix verb expressing communication, perception or cognition. We then collected the corresponding Bible verses from the later translations that were examined.Footnote 5

Methodically, our study aligns with historical corpus linguistics, an approach that views language as a dynamic phenomenon subject to change over time, examined empirically (Krug et al. Reference Krug, Schlüter, Rosenbach, Krug and Schlüter2013, Vartiainen & Säily Reference Vartiainen and Säily2020). Our primary focus is to analyse the frequency of constructions diachronically. Examining these frequencies allows us to observe linguistic changes over the studied time span. To understand these changes, we consider the socio-historical context of each Bible edition as well as the linguistic features of the verses that undergo transformation. Statistical methods were applied to evaluate the significance of the changes happening between the studied Bible translations. Our approach is corpus-based rather than corpus-driven (see McEnery & Hardie Reference McEnery and Hardie2012), as we use the data to explore our hypotheses.

One challenge in diachronic research is the availability and comparability of data (Krug et al. Reference Krug, Schlüter, Rosenbach, Krug and Schlüter2013, Vartiainen & Säily Reference Vartiainen and Säily2020). For this reason, we focus on biblical translations, examining versions of the same text across different periods. It should be noted that the observations made about the language of the Bible are not directly generalisable to other genres.

5. Referative constructions and että-clauses in the Finnish editions of the New Testament

In this section we first distinguish the frequency of the structures we examined within our data. We then look at the contexts in which the changes occur and why, focusing on switch-reference marking (Section 5.2) and the matrix verbs of the constructions (Section 5.3).

5.1 Distribution of constructions

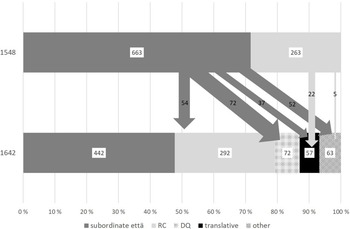

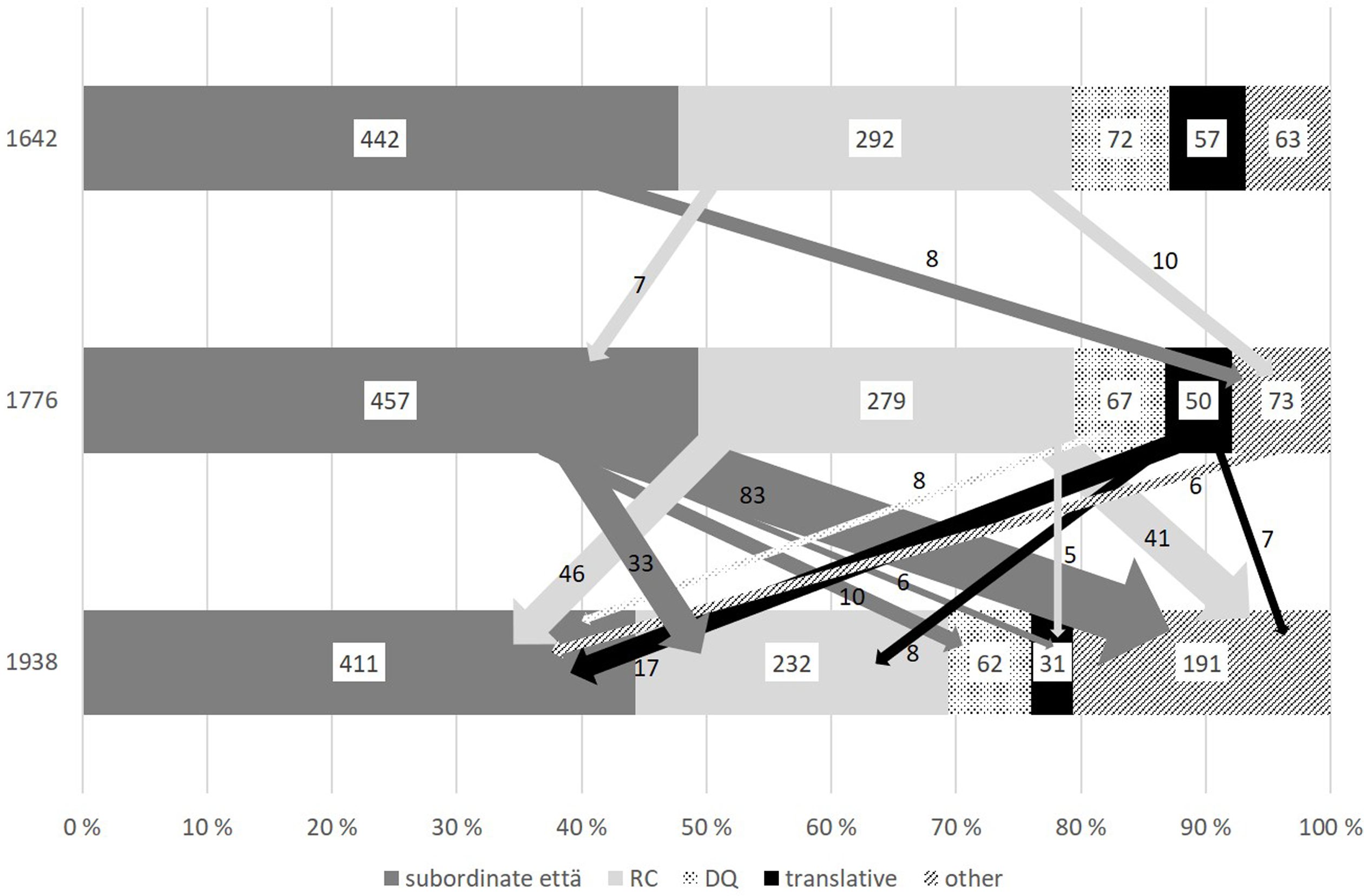

Figure 1 illustrates the changes in the frequency of RCs and corresponding että clauses from 1548 to 1642. As detailed in Section 4, the data collection focused on RCs and että clauses identified in the 1548 New Testament. Consequently, other constructions present in the earliest version were not included in the data. Thus, it is not possible to assess whether Agricola’s other constructions were later replaced by RCs or että clauses in the 1642 or subsequent versions. In coding the later translations, direct quotes (DQs) and translative constructions are distinguished from other constructions. To maintain clarity in Figures 1–3, only changes involving more than five occurrences reformulated into another construction are marked with arrows.

Figure 1. Distribution and change of constructions of reported discourse, perception, and cognition from 1548 to 1642.

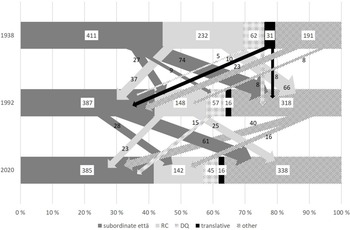

Figure 2. Distribution and change of constructions of reported discourse, perception, and cognition from 1642 to 1938.

Figure 3. Distribution and change of constructions of reported discourse, perception, and cognition from 1938 to 2020.

Previous studies (Ikola et al. Reference Ikola, Palomäki and Koitto1989, Häkkinen Reference Häkkinen1994:495–496, Mielikäinen Reference Mielikäinen2014:38) have noted that the 1642 translation – as well as the 1776 version – generally favours non-finite structures. Rapola (Reference Rapola1942:17) provided examples of verses where että clauses used by Agricola were converted to RCs in 1642, suggesting that että clauses may have resulted from literal translation. Figure 1 reveals a significantly higher number of että clauses in the 1548 translation compared to the 1642 edition.

Itkonen-Kaila (Reference Itkonen-Kaila1997:72–73) argued that the influence of classical languages is most evident in the Gospels, which are narrative texts, while Swedish and German influenced the structures in the New Testament Letters, where Agricola followed Luther’s explanations. Our quantitative analysis of the frequency of RCs and subordinate clauses revealed significant differences between books, although they may be more closely connected to the topics of the texts than to the source texts. In the 1548 translation of the Letters, the proportion of että clauses is higher than in other sections (88% versus the average 72%, p = 0.039). However, when considering the ratio of RCs to että clauses, attention is particularly drawn to the Book of Revelation rather than the Gospels. In Acts of the Apostles, että clauses account for 60% of the data and in the Gospels 52%, differences to the average not being statistically significant. In Revelation, however, että clauses only account for 21% (p < 0.001). The high frequency of RCs in Revelation was also noted by Forsman Svensson (Reference Forsman Svensson1983:130). As the Book of Revelation is largely a report of what was seen and heard, the frequency of RCs is at least partly explained by the number of occurrences of the matrix verbs nähdä (‘to see’) and kuulla (‘to hear’), which favour RCs (see Section 5.3).

Figure 1 demonstrates that many että clauses were changed to RCs, DQs, and other constructions in the 1642 edition. The shift from subordinate clauses to DQs is linked to the fact that many että clauses, used as the object of the verb sanoa (‘to say’), were converted into DQs by omitting the conjunction. Another factor favouring non-finite structures in general is that both subordinate clauses and RCs were changed to non-finite structures formed with the translative case (see examples 6 and 7 above).

Figure 2 shows how the distribution of constructions evolved further in the following editions from 1776 and 1938. From 1642 to 1776, changes were minor. However, the tendency to favour RCs seemed to be reversing, with RCs being replaced by subordinate clauses and other constructions. In contrast, in 1938, significant changes were made. Many verses were completely reformulated: both että clauses and RCs were transformed into other structures. Eighteen että clauses that had been changed in 1642 to translative constructions (and preserved in 1776) reverted to että clauses in the 1938 edition, while five were changed to RCs. However, of the RCs changed to translative constructions, fewer (five occurrences) reverted to RCs, with more being changed into other structures (eight occurrences), such as essive case marking (example 8). This trend aligns with Forsman Svensson’s (Reference Forsman Svensson1983:291) observation that in the twentieth century, the meaning of the translative construction diverged from that of RCs.

In the 1938 edition, että clauses, in particular, were replaced with other constructions. Similar changes occur in the newer editions as well, reflecting an effort to modernise biblical language by employing structures more natural to the Finnish language. In our analysis, we coded as other constructions instances where, for example, a supporting pronoun is added to the construction (example 9), or where the head of the että clause is changed from a verb to a noun (e.g. toivoa ‘to hope’ replaced by toivo ‘hope’). Että clauses were also replaced by indirect questions, especially ones beginning with the word kuinka (‘how’).

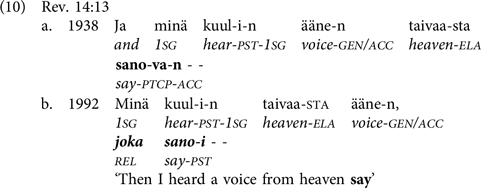

Figure 3 illustrates that in the three most recent translations examined, the changes are multidirectional. RCs decrease significantly between the 1938 and 1992 translations. In this period, many RCs used with the verbs nähdä (‘to see’, 36 occurrences) and kuulla (‘to hear’, 16 occurrences) are reformulated (see Section 5.3). With these verbs of sensory perception, in the later editions, a relative clause (example 10) or an indirect question beginning with kuinka ‘how’ is often used. The RC frequency between the data from different books of the Bible varies between 22% (Revelation) and 13% (Letters) even in the latest version, but the differences are no longer statistically significant.

Our analysis shows that että clauses and RCs are often genuine alternatives to each other, as they are used interchangeably in the same verses across different editions. The number of RCs decreases most markedly in the two most recent translations, while the number of että clauses remains relatively stable over the centuries. Despite the cautious attitude of contemporary prescriptive grammar guides towards these non-finite structures, RCs are still widely used in the most recent translations for mobile device users and audiobook listeners.

However, it should be noted that our data collection was based on the structures of the first translation. In our data, both että clauses and RCs decrease as they are converted into other structures. Although these other structures sometimes reverted to earlier formulations, a limitation of our data is that they do not capture whether more recent editions translate some verses – where Agricola used other structures – as RCs or että clauses. It remains for future research to determine the extent to which the second and third types of Finnish RCs are used, as these are rare or absent in the present data.

5.2 Same-subject and different-subject constructions

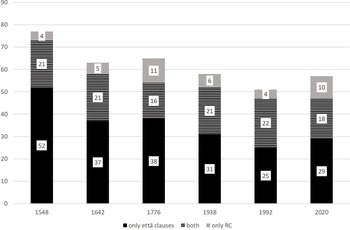

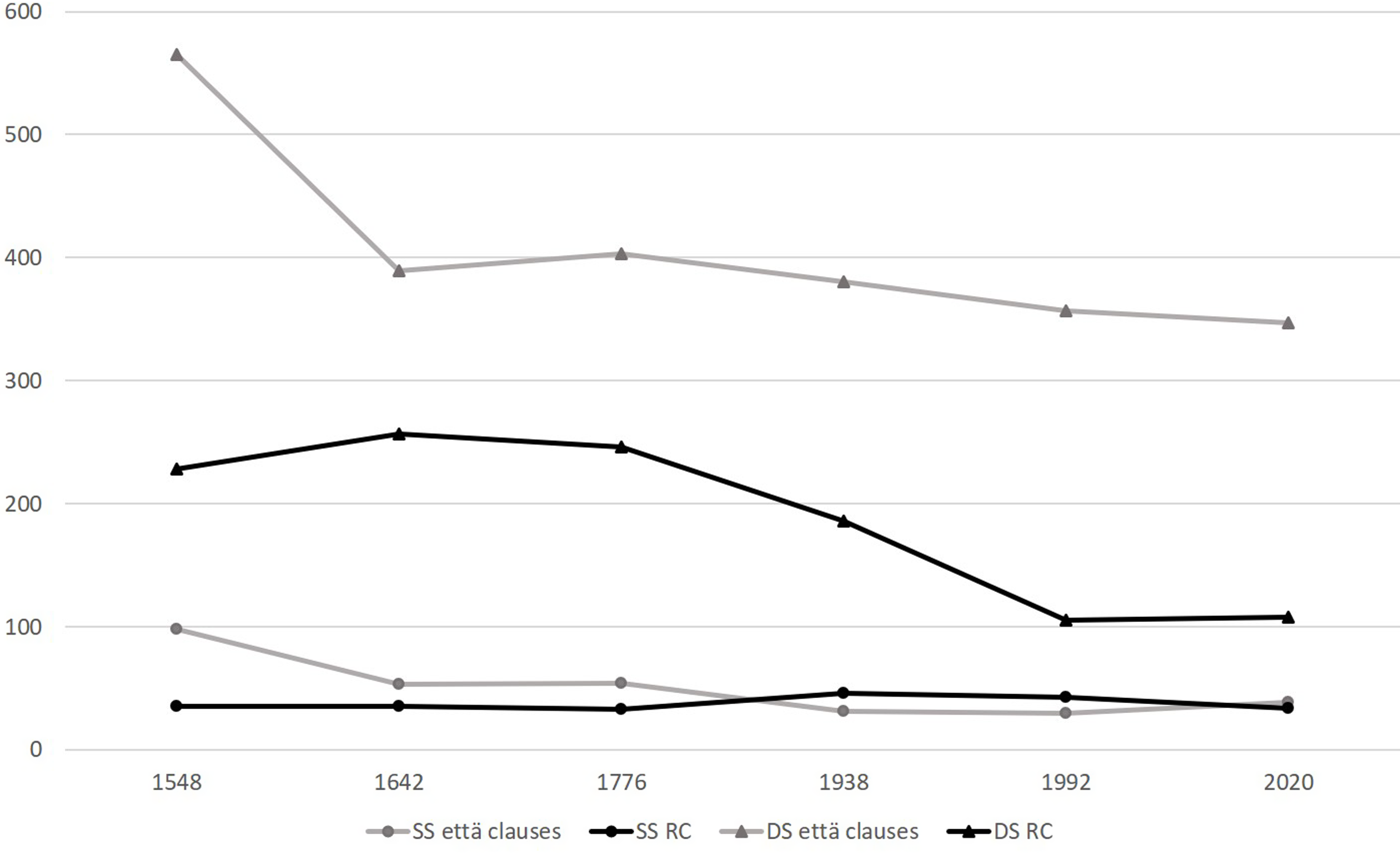

In Figure 4 we show how RCs and että clauses are distributed into SS and DS occurrences in each translation. In the first three translations, no statistically significant difference between että clauses and RCs was found regarding whether they express SS or DS structures. However, in the 1938 translation, a difference becomes apparent and increases further in the 1992 translation: RCs are reduced, particularly in structures where the semantic subject of the RC is different from that of the matrix clause. As presented in Section 3.1, genitive attributes of DS RCs make the structures more complex than SS RCs, which are marked with possessive suffixes. At the same time, the number of SS että clauses decreases. We assume that from the twentieth century onwards, translators have paid increasing attention to the complexity of structures. According to Hanna Lappalainen (oral communication), a linguist involved in the 2020 New Testament translation working group, RCs were not deliberately avoided in the text, but sentence length was considered. In the most recent translation, the number of different-subject RCs does not decrease further, while the number of SS että clauses slightly increases.

Figure 4. The number of RCs and että clauses having the same or different subject as the matrix clause in the Finnish Bible editions.

In Section 3.1 we presented a small search in the contemporary conversational Finnish corpus (ArkiSyn), considering SS and DS RCs. Although only a few occurrences were found, their distribution suggests that in everyday conversations, SS RCs could account for more than half of the use of the first type of RCs. Of course, the topic of the text or conversation seems to play a role in the occurrence of this feature. We suggest that the tendency of modern biblical language to prefer SS RCs as the overall use of RCs declines may indicate that SS RCs are perceived as easier and more accessible structures. It would be worthwhile investigating changes in the frequency of SS and DS constructions further across different types of spoken and written language data available, for example, in newspapers or academic texts.

The distribution of SS and DS RCs is naturally linked to matrix verbs, as some of verbs used in the matrix clauses prefer DS occurrences. For example, the sensory perception verbs nähdä (‘to see’) and kuulla (‘to hear’), which are the most frequent matrix verbs in the data, are more commonly used with DS structures.

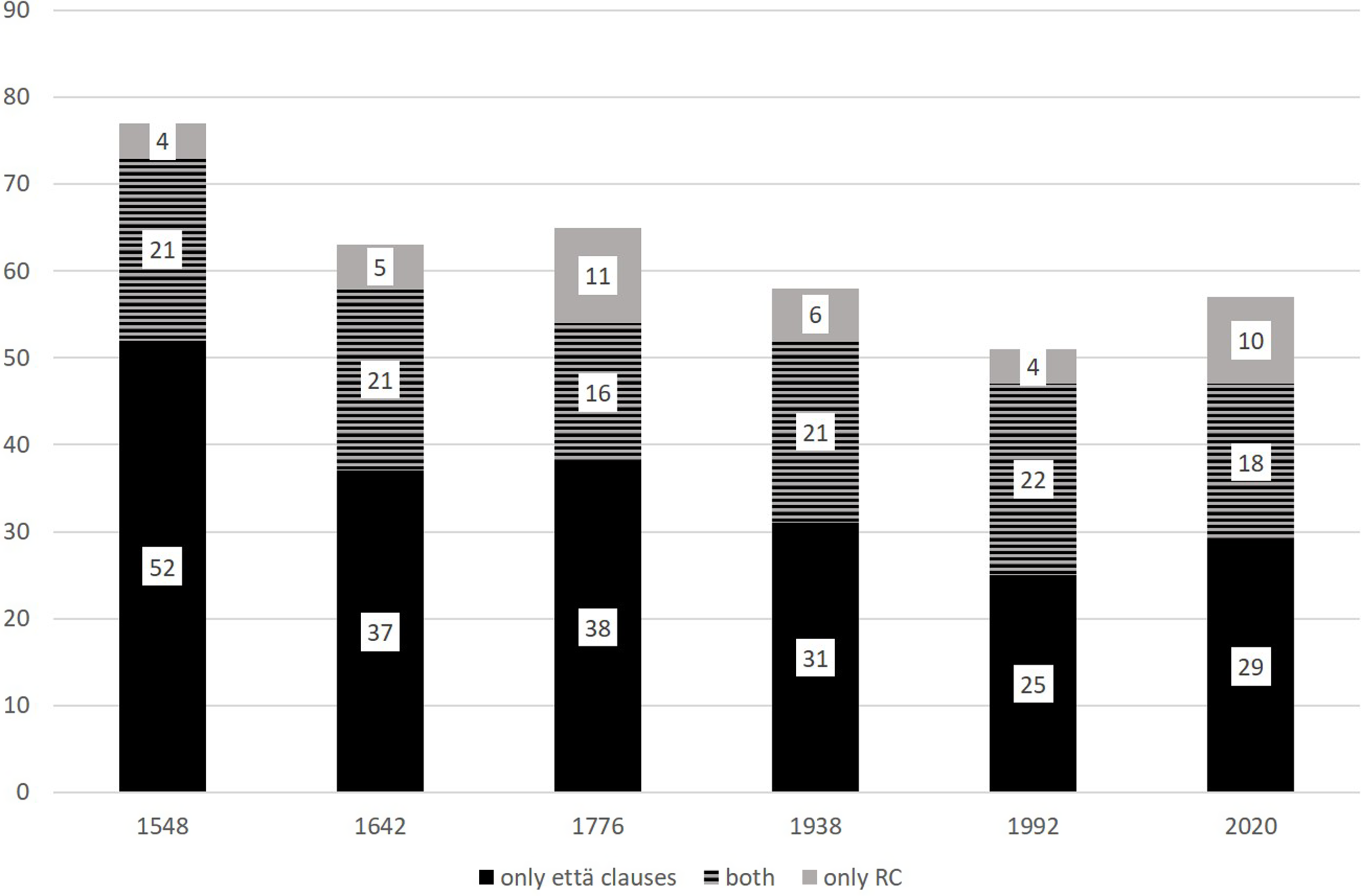

5.3 The set of matrix verbs used with referative constructions and että clauses

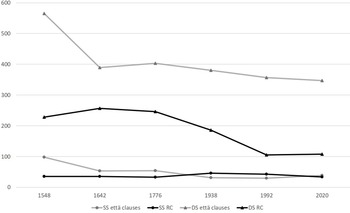

In this section we examine whether the set of matrix verbs used with RCs and että clauses changed over the time span from the sixteenth century to the present. Figure 5 depicts the number of verb lexemes used with the constructions examined in different editions of the Bible. There is no clear change in the number of verb lexemes used with RCs in the data, only a slight downward trend in the number of lexemes used with että clauses. This trend is explained, in part, by the addition of supporting pronouns in että clauses (see example 9 in the previous section).

Figure 5. Number of matrix verb lexemes for RCs and että clauses in the Finnish Bible editions.

Että clauses are more versatile than RCs in the data: in all translations, there are many matrix verbs with which että clauses are used but not RCs. For these verbs, some other non-finite structure is more typical than an RC as an alternative to an että clause. For instance, the verbs rukoilla (‘to pray’), neuvoa (‘to advise’), and pyytää (‘to ask’) are used with MA-infinitive illative forms (VISK:§121). The alternation between että clauses and MA-infinitive illative forms is already present between the 1548 and 1642 translations (see example 11).

Based on our intuition as native Finnish speakers, RCs would be possible with some relatively frequent matrix verbs that only occur with että clauses in the data. Such verbs include lukea (‘to read’, 10 occurrences in all editions combined), kirjoittaa (‘to write’, 35 occurrences), vannoa (‘to swear’, 15 occurrences), and rukoilla (‘to pray’, 173 occurrences). Whether this is due to influence from source languages could be determined by a systematic examination of the corresponding structures in the source texts. Some verbs, e.g. muistaa ‘to remember’, pelätä ‘to fear’, and tahtoa ‘to want’, were only used with että clauses in the first edition but later they also occur with RCs.

The number of verb lexemes used in the data with both että clauses and RCs remains similar throughout the period. The five most common matrix verbs in both structures – nähdä (‘to see’), kuulla (‘to hear’), luulla (‘to think, to assume’), sanoa (‘to say’), and tietää (‘to know’) – are consistently used in all six editions, although their frequency varies between editions.

Thus, these structures show no signs of crystallising to accompany only certain verbs. Most of the verbs that occur only with RCs in the data are individual occurrences, and we assume that in larger data, they could occur with että clauses as well. However, there are tendencies in the data for certain verbs to be significantly more frequent with one or another of the structures under consideration, despite their alternativeness. We show that these preferences also change in time.

As we presented above, the semantics of matrix verbs determine how natural it is to use them in SS or DS constructions. Of the typical matrix verbs of RCs, kuulla (‘to hear’) only occurs with DS constructions, as does nähdä (‘to see’), with a few exceptions. When the number of RCs used with these verbs was reduced in the 1938 edition, the number of DS constructions was also reduced.

When considering the verbs used in the data as matrix verbs of both SS and DS RCs, the tendency in the twentieth century still seems to be for the number of DS RCs to decrease. For example, of the 15 DS RC structures having the verb tietää (‘to know’) as a matrix verb in 1938, 13 were changed to tietää että clauses in the 1992 edition. Only two of the five SS RCs with tietää were changed: one into an että clause and the other by reformulating the verse completely.

Next we will look in more detail at the changes that have occurred in some of the most frequent matrix verbs that are used with both structures. We will focus on translations where the most significant changes in the number of structures were found. First, we examine the differences in the matrix verbs used between the 1548 translation and the subsequent 1642 translation. Then, we will look at how the 1938 translation differs from the 1776 translation and how the 1992 translation differs from the 1938 translation.

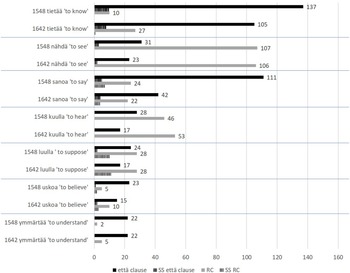

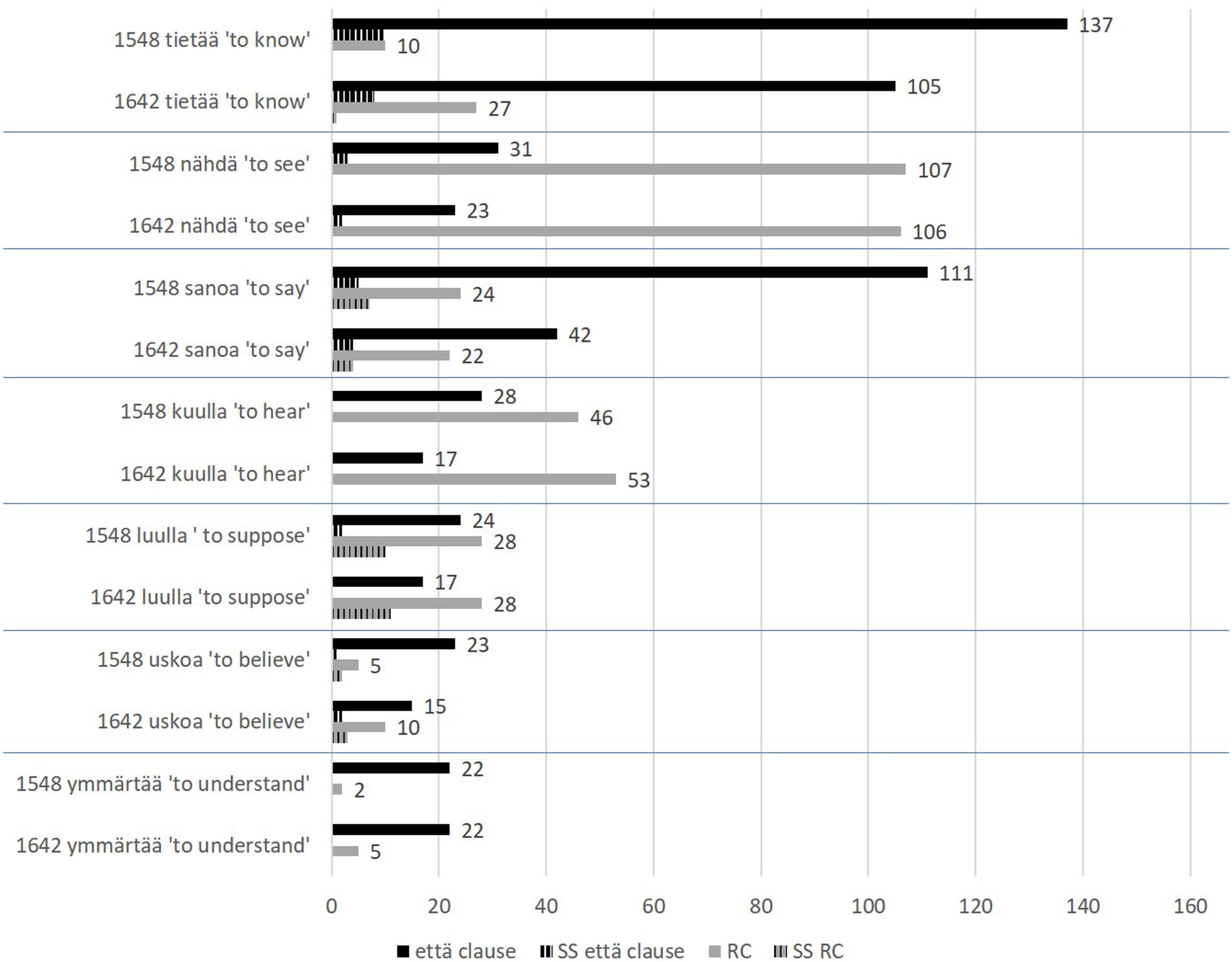

In the oldest translation of the New Testament (1548), both RCs and että clauses appear with a total of 21 matrix verb lexemes. Most of these verb lexemes only occur once or twice. Figure 6 shows the frequency of 7 most common matrix verbs (N > 20) used with RCs and että clauses in Agricola’s translation (1548). A separate bar marks the share of SS occurrences.

Figure 6. The most frequent matrix verbs of RCs and että clauses in the 1548 and 1642 editions.

As we have shown, between the 1548 and 1642 versions, the number of että clauses decreases and the number of RCs increases. Figure 6 shows that RCs increase with some of the most common verbs, particularly tietää (‘to know’) and kuulla (‘to hear’). The verb tietää generally prefers että clauses, likely because the phenomena to be known can be complex to verbalise. However, the share of RCs among the objects of the verb tietää first increases and then decreases (see Figure 7). The relationship between the two most common perceptual matrix verbs, nähdä (‘to see’) and kuulla (‘to hear’), is interesting: both prefer RCs but, in the early translations, nähdä more strongly than kuulla. Perhaps due to the analogy with nähdä, the number of RCs used with kuulla increases. In the twentieth-century editions, however, both decrease with RCs (see Figure 7). In the case of että clauses, a significant decrease occurs with the verb sanoa (‘to say’): many of these structures become direct quotes, so that only the apparently superfluous conjunction että is omitted, and the wording of the quoted part does not usually change much.

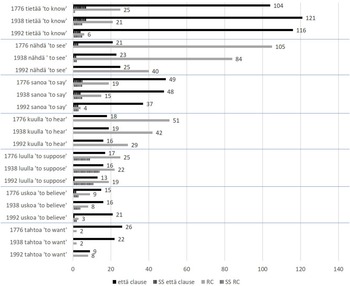

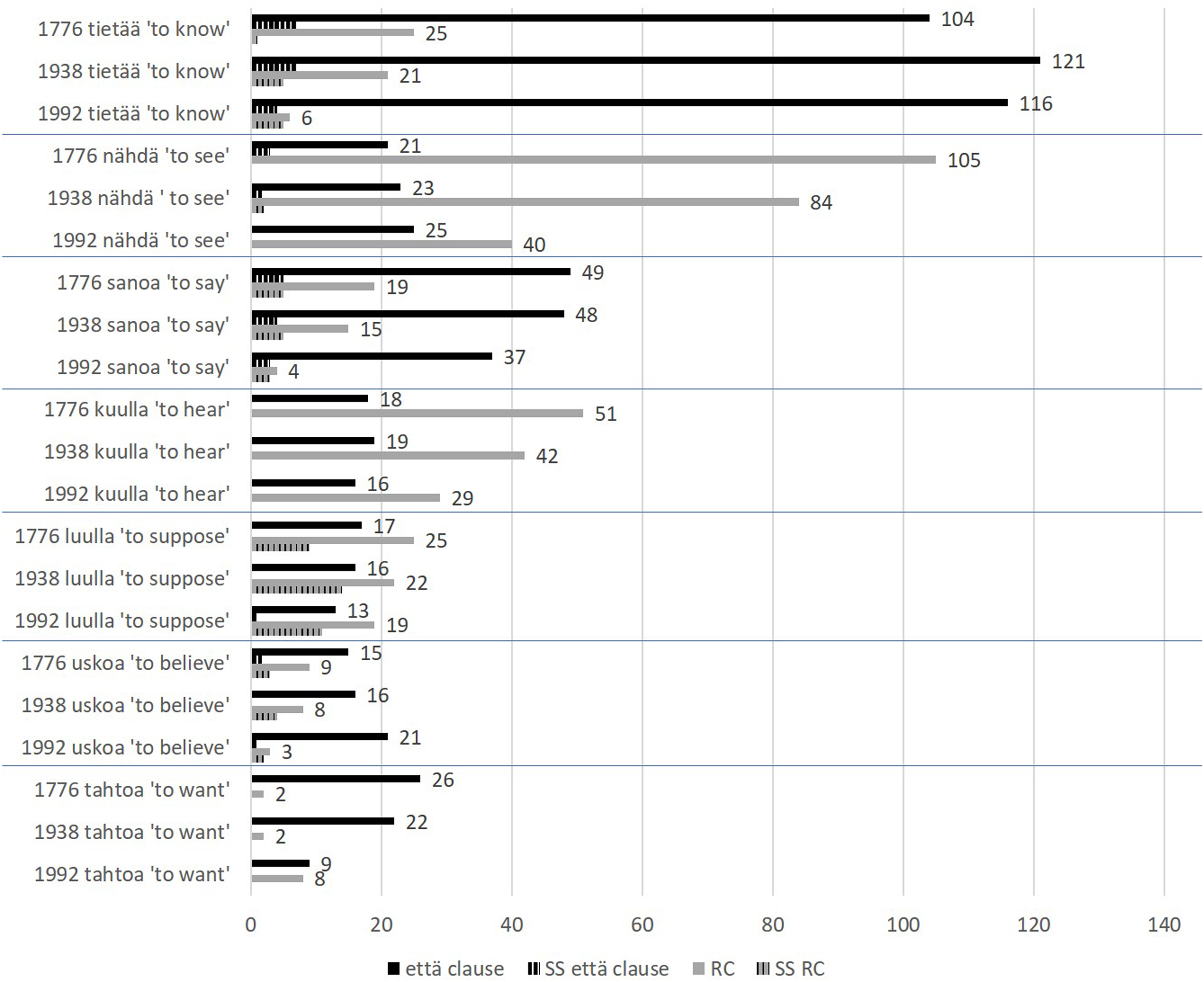

Figure 7. Matrix verbs of the RCs and että clauses in the 1776, 1938 and 1992 editions.

In the 1776 translation, both RCs and että clauses appear with a total of 16 matrix verb lexemes; in 1938, 21 lexemes, and in 1992, 22. The distribution of seven most frequent verbs (N > 20) is presented in Figure 7. The set of verbs differs from that shown in Figure 6 in that the verb ymmärtää (‘to understand’) is replaced by the verb tahtoa (‘to want’). In the 1548 translation, tahtoa was not used with RCs, and in 1992, ymmärtää only occurs with että clauses. The verb tahtoa ‘to want’ is a peculiar case in the sense that although its meaning would fit being used with both DS and SS RCs, only DS RCs are used. When the semantic subject of something that is wanted is the same as the person wanting, another non-finite form, the A-infinitive is used (e.g. tahdo-n lähte-ä want-1sg leave-inf ‘I want to leave’ instead of *tahdo-n lähte-vä-ni want-1sg leave-ptcp-poss.1sg).

From 1776 to 1992, the data presented in Figure 7 show a general decrease in the use of RCs, with a fairly steady decrease across most typical matrix verbs. Figure 7 also illustrates that for these verbs, DS RCs are the ones primarily declining. Regarding the complements of the verb luulla (‘to think, to assume’), almost all SS occurrences are RCs, while DS occurrences are että clauses. The verb tahtoa ‘to want’ behaves contrary to the observed tendency, as its use with RC increases in the 1992 edition. The 2020 translation, by the way, introduces to biblical language another verb with the same meaning, haluta,Footnote 7 which also occurs fairly evenly with both että clauses and DS RCs.

The structures associated with the verb sanoa (‘to say’) undergo another change in the twentieth-century editions, with both RCs and että clauses decreasing. The 1992 edition shows a broader range of matrix verbs than earlier translations, including väittää (‘to claim’) as well as other verbs indicating oral communication, such as puhua (‘to talk’), huutaa (‘to shout’), and kysyä (‘to ask’), which replace sanoa.

6. Discussion and conclusions

In this article we have examined the changes in two constructions of reported discourse – perception and cognition – specifically, referative constructions formed with participles (RC) and subordinate clauses beginning with the conjunction että in Finnish Bible translations throughout the history of written Finnish. Previous research by Forsman Svensson (Reference Forsman Svensson1983, Reference Forsman Svensson1986) already examined RCs and translative constructions in seventeenth-century Finnish and provided insights into earlier and later language use. In this paper we have extended that research by offering a quantitative comparison of different versions of the same text – the Finnish editions of the New Testament – and continuing the examination to the twenty-first century. The focus has been on the alternation of RCs and että clauses, their use as SS or DS constructions and their matrix verb lexemes.

RCs are interesting non-finite structures in Finnish, partly because, like other non-finite constructions, they are considered typical features of Finno-Ugric languages. However, RCs are also influenced by foreign languages, such as the Latin ACI construction. We have shown that RCs have been a stable and permanent part of the Finnish biblical language over the nearly 500-year period studied. Although RCs appear in old dialects, they are more frequent and are used differently in written language than in colloquial speech. A challenge in reliably comparing different datasets and adopting a diachronic perspective is that the genre and topic of texts influence which matrix verbs are used and how frequently RCs appear.

Despite these challenges, our study demonstrates that RCs were relatively frequent in Agricola’s 1548 text and became even more widespread in the subsequent editions in 1642 and 1776. RCs were apparently regarded as part of the written standard of the time, and early grammar books even preferred them to subordinate clauses (e.g. von Becker Reference von Becker1824:243). However, the attitude towards RCs became more cautious over time. Modern language regulation sometimes considers RCs problematic and hard to follow (e.g. Kielitoimiston ohjepankki; Selkokeskus). Despite this, RCs remain part of biblical language even in the 2020 version, which is designed for mobile device users and audiobook listeners.

By comparing different versions of the New Testament, we have observed how RCs and subordinate clauses can serve as alternatives to each other. In grammar books, RCs are often presented alongside corresponding että clauses, and both structures have been used with a wide variety of verbs throughout history in Bible translations. Subordinate clauses are more versatile than RCs; they can be used with verbs for which a non-finite structure other than RC would be more natural. Että clauses also undergo changes when biblical language adapts to modern standards, such as the addition of supporting pronouns to subordinate clauses. It is impossible to examine RCs without also considering the Finnish translative construction, as detailed by Forsman Svensson (Reference Forsman Svensson1983). In the 1600s and 1700s, participle verb forms in the translative case were favoured, but their use in contexts of reported speech, thought, and perception has diminished in more recent texts.

We have linked changes in the frequency of RCs and subordinate että clauses and their matrix verbs to the switch-reference marking in Finnish RCs. In biblical language, both RCs and että clauses are typically used with a different semantic subject from the main clause. However, from the early twentieth century, a significant shift occurs in the proportion of SS RCs: as RCs decrease, it is DS RCs that decline in particular. Given the morphological differences in semantic subject marking between SS and DS RCs, we see an effort to reduce complex DS RCs, where the subject is marked by a genitive noun phrase. This trend may bring written Finnish closer to spoken language, where SS RCs seem to be preferred in contemporary everyday conversation. However, this finding requires further research. Additional research is also needed to determine why almost none of the second-type RCs were found in the first Finnish translation of the New Testament and whether these second-type structures, which seem to be relatively widespread in spoken language, appear in more recent translations.

Various factors influence the development of matrix verbs. First, the number of että clauses used with the verb sanoa (‘to say’) decreases because these structures are converted into direct quotations. Later, both RCs and subordinate clauses with this verb decline, as sanoa is replaced by a more varied set of speech act verbs. The most common sensory perception verbs, nähdä (‘to see’) and kuulla (‘to hear’), seem to converge in an analogous manner. The extent to which the structures used with different verbs in different periods reflect the source texts remains an area for further investigation.

Data availability statement

The data were derived from public resources mentioned in the Appendix. The coded dataset as a .txt file is openly available at Zenodo data archive: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14195898.

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers of the Nordic Journal of Linguistics for their insightful comments that helped to develop the paper to its current form. We also thank the FiRe research team for their support and encouragement. The work was funded by the Research Council of Finland (project number 348899).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.