1. Introduction

The pioneering work on Easy Language in Sweden is internationally regarded as exemplary. However, agreement on the definition of Easy Swedish is still lacking.

This literature review aims to describe how Easy Swedish has been understood in previous research. By international comparison, Easy Language was established early in Sweden; the first books were published in the 1960s and a newspaper in the 1970s (Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021:529). The ongoing change over recent decades towards a more inclusive society and more demanding legislation on accessibility has resulted in increasing ambitions to meet the needs of struggling readers and a growing interest in producing Easy Language materials (e.g. Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2018:37; Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021:537–539). By contrast, only a limited amount of linguistic research has been conducted on Easy Swedish, and most studies have been master’s or bachelor’s theses. Some research has also been conducted in other disciplines such as literature, pedagogics, translation studies, library science, and computer science. However, Easy Swedish has not been considered a research field, and no study has previously brought together this wide range of perspectives and approaches.

Accessible language has been used as a subordinate concept including both Easy Language and Plain Language (Moonen Reference Moonen, Camilla and Ulla2021), with accessible communication as a somewhat wider concept (Maaß Reference Maaß2020).Footnote 1 These concepts can be conceptualised in different ways (Hansen-Schirra et al. Reference Hansen-Schirra, Abels, Signer and Maaß2021:18). As this article focuses on Easy Language, it does not present a definition of the other concepts. A review of Swedish research on Plain Language, klarspråk in Swedish, has been published by Nord (Reference Nord2017). (For a further discussion concerning Plain Language, see Nord Reference Nord2017.)

In this article we present a meta-narrative review (Section 2.1) of research on Easy Swedish, thus constructing a larger picture that may serve as a starting point for future researchers. We aim to expose possible tensions among the papers covered in our review and to describe the diversity and complexity of their contributions to the emerging research field of Easy Swedish. As regards the historical context of our material, we aim to identify the key scientific discoveries or insights that have led to further work, agreements, or perceptions considered self-evident.

To describe how Easy Language is understood in our material, we present the following research questions.

-

1. Which terms are used and how are they defined?

-

2. Is the target group described in different ways?

-

3. Which ideologies, discourses, or values justify Easy Language?

In answering these questions, we also observe common references and intertextualitiesFootnote 2 regarding the conceptualisation of Easy Language. As discussed in this article, the definition of terms such as Easy Language is challenging. We use the term ‘Easy Language’ for written texts as well as both spoken language and sign language, and ‘Easy Swedish’ when specifically focusing on the Swedish language, either spoken or written.Footnote 3 By ‘text’, in this context, we mean language realised in writing, for instance, on paper or a website.

The outline of the paper is as follows. Section 2 describes the methods and materials of the study. Section 3 in turn contains a presentation and analysis of the findings. Finally, Section 4 discusses the results of the study and reflects on the implications for future practice, policy, and research.

2. Methods and materials

Next we describe the meta-narrative method (Section 2.1), the data collection process (Section 2.2), and the material collected and used for analysis (Section 2.3).

2.1 Meta-narrative review method

This article presents a meta-narrative literature review, adapting a method first introduced by health scientists (Greenhalgh et al. Reference Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate, Kyriakidou and Peacock2005, Reference Greenhalgh, Potts, Wong, Bark and Swinglehurst2009). They present the method as an approach for sorting and interpreting studies in a more pragmatic and interpretive manner than a systematic literature review. The mission of the reviewer is to collect similar studies into comparable groups and show how the same research problem has been conceptualised and investigated in these groups but has possibly resulted in contradictory findings. The meta-narrative method can serve as a tool for sensemaking by systematically producing storied accounts of relevant research traditions, allowing the reviewer to describe and interpret the studied material.

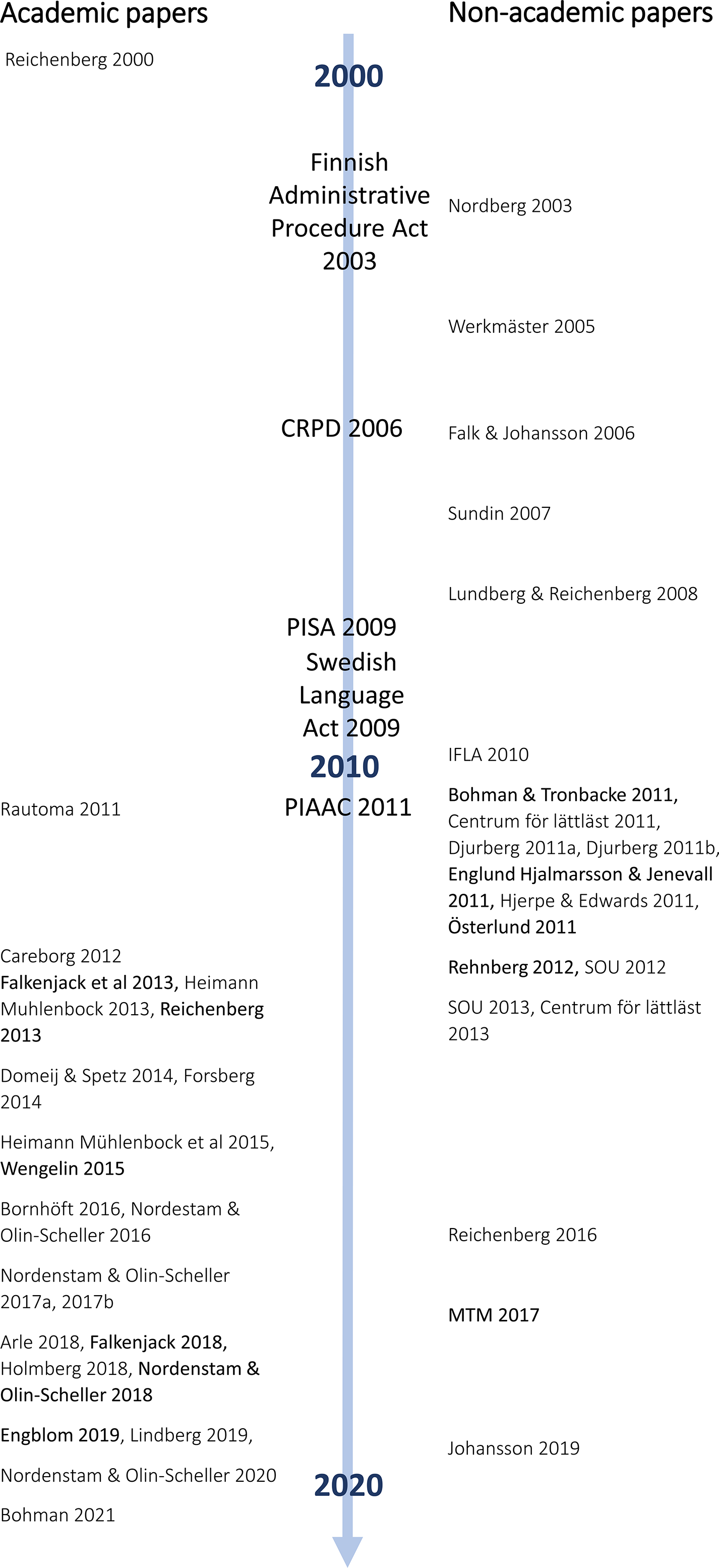

When applying this methodology in a health science study of English-language papers on information for people with an intellectual disability, Chinn and Homeyard stated that ‘the focus is on systems of meaning-making associated with different paradigms, rather than determining any one underlying truth’ (Reference Chinn and Homeyard2017:2). To manage our heterogeneous data set, we adopted the key strategies of the meta-narrative review method (Figure 1), dividing the papers into groups using recent guidance (Chinn & Homeyard Reference Chinn and Homeyard2017) as a benchmark.

Figure 1. Systematic review process.

Greenhalgh and colleagues offer five guiding principles that underpin the method: pragmatism, pluralism, historicity, contestation, and peer review (Reference Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate, Kyriakidou and Peacock2005:427–428). The principle of pragmatism implies an initially exploratory search phase, emergent rather than truly systematic, and a dialogue with internal and external experts feeding into the decision-making process. In the present study, a dialogue with professionals working with Easy Swedish and input from our research project team was important in the review process, as was drawing on our own experience in the field. According to the principle of pluralism, no universal solution or single theory can explain all findings if the body of evidence is complex. As the papers included in our study vary considerably, part of our mission is to expose possible tensions and describe the diversity and complexity of their contributions to the emerging field of Easy Language. The principle of historicity stresses the need to take into account the historical context of each paper and/or author: Which key scientific discoveries or insights have led to further work, agreements, or perceptions seen as self-evident? We took into consideration the order and time of publishing and the historical context of the papers included in our material. In accordance with the principle of contestation, we saw the heterogeneity of aims, methodology, and results as actual data. The principle of peer review stresses the importance of critical reflection on one’s own work and testing one’s findings against the judgement of others.

2.2 Material

The papers included in this review were collected through both systematic database searches and more intuitive methods (Figure 1).

We conducted a systematic literature search using the Swedish key words lätt språk, lätt svenska, and lättläst (Easy Language, Easy Swedish, and Easy to Read). Following the practice and advice of senior researchers, we conducted searches in the international databases MLA, PsycINFO, and PubMed, and in the national Swedish and Finnish research databases Libris, Helka, Doria, and DIVA. Literature searches in other large international databases such as SCOPUS or Google Scholar generated a large amount of irrelevant material, and the relevant papers were duplicated in the search results in the above-mentioned Finnish or Swedish databases, so they could thereby be eliminated from the search process.

The next search phase consisted of intuitive search methods. We conducted a ‘snowballing’ search (Greenhalgh et al. Reference Greenhalgh, Potts, Wong, Bark and Swinglehurst2009:420) to identify additional research by examining the reference lists and citations in the material we had collected so far. Once we had identified researchers with an interest in Easy Swedish, we discovered further publications by using their names as keywords or contacting them directly. Advised by a senior researcher, we conducted a manual search for linguistic papers in the linguistic academic journal Sprog i Norden and the conference publications Svenskans beskrivning and Svenskan i Finland.

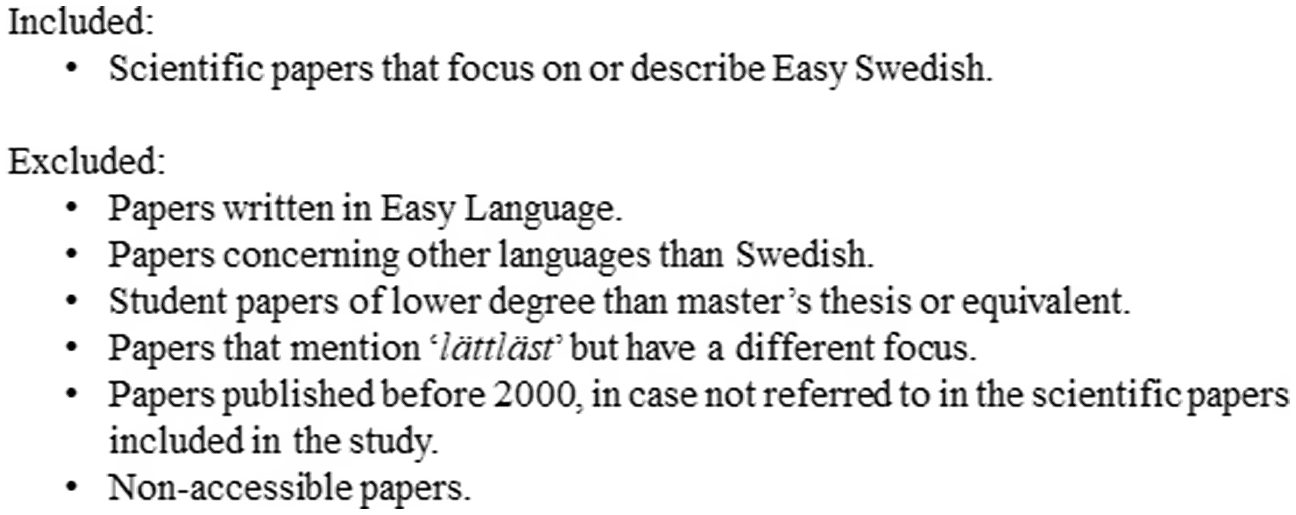

After the search phases described above, we screened the titles and abstracts for eligibility according to our inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 2) and selected 23 academic papers from different disciplines and levels of publication, listed in Appendix A. The systematic search methods led us to select 15 academic papers for our study, and the intuitive search methods added 8 more. Some of them were master’s theses or equivalent, so only the papers published in academic journals had been subjected to the peer-review process. Subsequently, as part of the data extraction process, we tabulated the key features of the studies: discipline(s), aims, methodologies, materials, and context. With these tables in mind, we read, reread, and discussed our selected studies to be able to group the papers with similar features.

Figure 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

In addition to our core material of academic papers, we have listed 27 non-academic papers or documents used as references in our academic material for describing and defining Easy Language (Appendix B). These texts were not academic but played an important part in the conceptualisation of Easy Language.

3. Findings and analysis

After an initial presentation of how the material was divided into groups, this section describes the groups in separate subsections and lists their contributions to answering our research questions.

3.1 Grouping the material

The 23 academic papers in our material showed great heterogeneity in terms of aims, methodology, and results, which, according to the principle of contestation (Greenhalgh et al. Reference Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate, Kyriakidou and Peacock2005:428) constitute valuable data. The papers represented a vast range of disciplines: linguistics, computer linguistics, pedagogics, literary studies, communication studies, translation studies, and political science. An initial group division based on discipline generated incomparable groupings, as the research perspectives greatly differed within the disciplines, several studies were interdisciplinary, and some disciplines were represented in only one paper. The interdisciplinary studies were either co-written by authors from different disciplines or written by authors representing more than one discipline.

After the phases of adjustment, re-categorisation, and refinement, we collated the material into four groups (Table 1; see Appendix A for detailed information) based on aims, material,Footnote 4 and research focus. In the end, many but not all papers representing a certain discipline naturally fell into the same group.

Table 1. Grouping the material

3.2 Group 1: Descriptions of Easy Swedish

The authors of these academic papers (n = 5) – a linguistic article (Wengelin Reference Wengelin2015), a review article (Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021), and two master’s theses on linguistics (Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016; Arle Reference Arle2018) and one in translation studies (Piira Reference Piira2009) – aimed to describe Easy Swedish, focusing on different aspects of writing. The subjects of the papers varied, from the history of Easy Swedish (Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021) to the guidelines for writing Easy Language and Plain Language texts (Wengelin Reference Wengelin2015), and the various characteristics in small samples of texts (Piira Reference Piira2009; Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016; Arle Reference Arle2018).

The authors in this group used the term lättläst (Easy to Read). The term lätt att förstå (‘easy to understand’) occurred in one paper, which also noted that the term lättläst, even though it means ‘easy to read’, also includes spoken language (Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021:527–528). Easy to Read was defined as ‘adapted texts’ (Wengelin Reference Wengelin2015:5; Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021:535) or ‘a category of publications written for a specific audience’ (Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016:3). The term was also conceptualised through a comparison to more difficult texts (Piira Reference Piira2009:19; Wengelin Reference Wengelin2015:5; Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016:3; Arle Reference Arle2018). Easy Language texts were described or studied by comparing writing guidelines and novels (Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016; Arle Reference Arle2018). It was emphasised that writing Easy Language texts involves working on several distinct levels, from vocabulary to content (Piira Reference Piira2009:23; Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016:3, 69–70; Arle Reference Arle2018:12–13; Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021:534–535, 19, 20), but that no commonly agreed definition exists (Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021:534–536).

Citations or examples were often used to define or describe the concept. Most authors used non-academic references, such as Swedish and Finnish organisations or government bodies: Myndigheten för tillgängliga medier (MTM), Centrum för lättläst, LL-Center, and SelkokeskusFootnote 5 (Piira Reference Piira2009:19; Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016:3; Arle Reference Arle2018:7, 11–12; Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021:534–536). As mentioned earlier, these non-academic references are listed in Appendix B. The lack of research and/or need for research on Easy Swedish was emphasised (Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016:4; Arle Reference Arle2018:8, 11; Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021:529, 559–560, 569). In her paper on writing guidelines, Wengelin showed that not all guidelines are supported by research. Some of the guidelines are based on linguistic research, but the results have been simplified or misrepresented (Wengelin Reference Wengelin2015:14–15). This was discussed by Bornhöft, being the only instance of cross-referencing within this group (Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016:3). Bornhöft additionally showed that the authors of Easy Language books do not always follow the writing guidelines (Reference Bornhöft2016:69). With the exception of Wengelin, Easy Language texts were conceptualised as texts that had been published as – i.e. labelled as – lättläst.

The target group was described as heterogeneous, consisting of readers with different needs (Piira Reference Piira2009:21; Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016:3; Arle Reference Arle2018:12; Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021:535, 17, 44). It was discussed that one single text version might not fulfil the needs of all readers, often quoting non-academic references. A comment to the definition by the Swedish Centre for Terminology was quoted: ‘A person who is new to the Swedish language needs a different type of easy text to, for example, a person with an intellectual disability’ (Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021:535). The popular science book by Lundberg & Reichenberg (Reference Lundberg and Reichenberg2008; see Appendix B), stating that text characteristics such as short words and few consonant groups are important for a reader with dyslexia, while simple, everyday, and concrete words might be of greater importance for a reader with an intellectual disability, was also quoted (Arle Reference Arle2018:12). With reference to the popular science magazine Språktidningen, it was stated that ‘Easy to Read has been criticised for being a one-size-fits-no-one solution’ (Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016:10). However, this journalistic article refers to a debate with different opinions on Easy Language, and by quoting another part of the text, the opposite argument could be presented: that the same Easy Language text can work well for different subgroups (Rehnberg Reference Rehnberg2012).

In Sweden, Easy Language is linked to the human rights movement and is seen as part of the general development of society towards equality and accessibility, including legislative progress such as the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and the Swedish Language Act of 2009 (Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021:538). The purpose of Easy Language texts is seen to be to fulfil regulations concerning the right of all people to partake in information and culture (Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016:3), and the accessibility of public authority texts is considered an important ‘democratic question’ (Wengelin Reference Wengelin2015:2).

3.3 Group 2: Descriptions and evaluations of literature in practice

The papers in this group evaluated the actual use of Easy Language literature (n = 8). Five of the papers were published as part of a research project on literature for young readers (Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller Reference Nordenstam, Olin-Scheller, Höglund and Heilä-Ylikallio2016, Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2017a, Reference Nordenstam, Olin-Scheller and Warnqvist2017b, Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2018, Reference Nordenstam, Olin-Scheller, Johansson, Martinsson and Parmenius Swärdh2020), and the remaining three were master’s theses published by Finnish universities (Rautoma Reference Rautoma2011; Engblom Reference Engblom2019; Lindberg Reference Lindberg2019). The authors represented pedagogics, except for Engblom, who represented information studies. Nordenstam, Olin-Scheller, and Rautoma also represented literature studies.

These papers were more interested in studying the effects and purpose of the books than in describing them, even though the two aspects could be seen as somewhat difficult to separate. They focused on literature and used the term lättläst, which was defined as a ‘text type’ (texttyp) (Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller Reference Nordenstam, Olin-Scheller, Höglund and Heilä-Ylikallio2016:2, Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2017a:1, Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2018:35) or as a text with certain characteristics: ‘a text which is easy to decode and understand’ (Lindberg Reference Lindberg2019:17). Besides word-level and syntactic-level characteristics, other characteristics were mentioned: coherence and cohesion, content, structure, layout or form, and pictures (Engblom Reference Engblom2019:27; Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller Reference Nordenstam, Olin-Scheller, Höglund and Heilä-Ylikallio2016:105, Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2017a:3, Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2018:36; Lindberg Reference Lindberg2019:17–20). The lack of research on Easy Swedish was commented upon (Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller Reference Nordenstam, Olin-Scheller, Höglund and Heilä-Ylikallio2016:105, Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2017a:3; Lindberg Reference Lindberg2019:4). Most references to descriptions of the term were non-academic. However, the type of source or citation was not always clear – non-academic, course papers, and academic papers were similarly referred to and commented on (e.g. Rautoma Reference Rautoma2011:7–8).

The authors in this group focused on young readers, although they were aware of the heterogeneity of the target group (e.g. Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller Reference Nordenstam, Olin-Scheller, Höglund and Heilä-Ylikallio2016:103, Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2017a:2; Lindberg Reference Lindberg2019:18, 21).Footnote 6 Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller identified a risk of Easy Language books being ‘routinely used among groups of readers who also need more demanding texts’ (Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2017a:13).

This argument was elaborated in a later study:

There is a risk of too easy texts decreasing reading motivation ... In addition, we identify a risk of the text type becoming counterproductive for the students and teachers who choose Easy to Read as a ‘shortcut’ for reading lessons. Reading literature might thereby become more of an instrumental activity than an aesthetic experience. (Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2018:49)

In a later study, the same authors’ deductions were supported by their school librarian informants, who expressed a concern that Easy Language novels, especially novels aimed at teenagers and young adults, were read by people who would benefit more from reading more demanding texts (Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller Reference Nordenstam, Olin-Scheller, Johansson, Martinsson and Parmenius Swärdh2020:222)

Similar to most of the papers in Group 1, the concept was studied as books published and labelled lättläst, often as a small sample, although such publications are said to be ‘wide-ranging and [to] embrace many genres’ (Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2018:35). Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller concluded that the small sample of literature they studied was stereotypical, and that the teachers’ materials and work materials published as supplements to books provided an efferent reading experience lacking in aesthetics (Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller Reference Nordenstam, Olin-Scheller, Höglund and Heilä-Ylikallio2016:115, Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2018:48–49). Other researchers in this group reported positive reading experiences among interviewed readers (Rautoma Reference Rautoma2011:93–94; Engblom Reference Engblom2019:71; Lindberg Reference Lindberg2019:78). Both the publishers and authors justified producing Easy Language books in terms of democracy (Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller Reference Nordenstam, Olin-Scheller, Höglund and Heilä-Ylikallio2016:104, Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2017a:3, Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2018:35–36, 38, 40–41, 47). Although such books were criticised by school librarians, they were still highly appreciated as a means for immigrants to practise their reading skills and the Swedish language (Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller Reference Nordenstam, Olin-Scheller, Johansson, Martinsson and Parmenius Swärdh2020:222).

3.4 Group 3: Informative texts: Critical observations and reception studies

The papers in this group (n = 6) – three articles (Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2013; Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014), one doctoral thesis (Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2000), and two master’s theses (Careborg Reference Careborg2012; Holmberg Reference Holmberg2018) – examined informative texts. Public authority information, textbook texts, and health information were critically analysed from a user perspective. Two of the studies (Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2000, Reference Reichenberg2013) also focused on the reading comprehensibility of the texts. Some authors merely provided critical observations (Careborg Reference Careborg2012; Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2013; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014; Holmberg Reference Holmberg2018), whereas others offered development suggestions (Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2000:172–174; Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:59–61). Domeij & Spetz called for more studies of the varying needs of readers and how texts should be designed and formulated to meet these needs (Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:58).

All the papers focused on written texts and the term lättläst was used, except one paper published in English where ‘easy-to-read’ was used interchangeably with ‘reader-friendly’ (Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2013:65). A variation of definitions and conceptualisations was used: ‘text version’ (Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:25, 27, 29, 30), ‘text genre’ (Careborg Reference Careborg2012:11), texts with certain characteristics (Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2013:67), a type of ‘comprehensibility adaptation’ (Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:57), and a ‘format’ (Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:55; Holmberg Reference Holmberg2018:39). There was some variation in what characteristics were seen as typical for Easy Language texts. Some authors saw perspective, focus, structure, layout, and cohesion as characteristics of such texts (Careborg Reference Careborg2012:11; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:28), while others pointed out examples where Easy Language texts lacked the same characteristics (Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2013:68; Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:56). Easy Language texts were also described in relation to other (more difficult) texts (Careborg Reference Careborg2012:12; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:28). Non-academic references were used when describing the term (e.g. Careborg Reference Careborg2012:11–13; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:28). At times, the references were ambiguous; for instance, one paper listed certain characteristics that ‘supporters of easy-to-read texts maintain that such texts have’ without giving a reference (Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2013:67). It was claimed there was no general writing manner and that Easy Language texts published by government bodies could differ considerably from each other, although possessing certain similarities (Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014). It was also argued that text characteristics that are typical when writing Easy Language texts can counteract each other, which can further complicate the text (Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:33).

The need for research on Easy Swedish was often noted (Careborg Reference Careborg2012:18, 27, 28; Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2013:67; Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:58–59; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:28). The lack of research was also visible in the references; as pointed out above, these were often non-academic. The target group was commonly considered heterogeneous (Careborg Reference Careborg2012:17, 66; Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:54, 58–59; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:29–30). Three papers gave the same figure for the target group in Sweden – 25% of the population – but with different references. The reception studies showed different levels of comprehension of Easy Language or similarly adapted texts among different groups of readers (Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2000, Reference Reichenberg2013). These results indicate the need for differently or individually adapted information for readers within the target group. The importance of future reception studies was also stressed, but to date, no such study has been conducted (Careborg Reference Careborg2012; Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014).

Changes in society – such as increased inclusion and more demanding legislation on accessibility – are noted as a motivation or justification for Easy Language (Careborg Reference Careborg2012:10–11, 18; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:25–26). The public authorities that had published the studied texts were viewed as exercisers of power, as they wrote and published the texts with an implicit demand for desired action or behaviour (Careborg Reference Careborg2012:64–65, 67; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:27, 37). These authorities were also seen as acting according to specific responsibilities related to certain legislation (Careborg Reference Careborg2012:22–25; Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:52; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:26). Forsberg suggested that public authorities use Easy Language texts as a tool for complying with the laws requiring authorities to use clear, comprehensible language (Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:40). On the one hand, the researchers in this group viewed Easy Language materials as a potential tool to help the intended readers comprehend texts. On the other hand, they considered it a risk that texts published as lättläst may be potentially written or used in an incorrect manner, resulting in poor (or no) comprehension. Public authorities tend to publish only one Easy Language version, targeting as many readers as possible (Careborg Reference Careborg2012:66; Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:54). The expectation is that the same text should be comprehensible to different groups of readers, such as those with intellectual disabilities and those learning Swedish as a second language (Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:58). However, as noted in several papers, needs differ within these target groups, and one Easy Language version, although comprehensible to some readers within the target group, might not be suitable for others (Careborg Reference Careborg2012:66; Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:54, 58; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:39–40). Some text characteristics that make a text easier for some readers make it more difficult for others (Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:54; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:33).

Most authorities produce Easy Language information without investigating reader receptions, and two separate studies found that only one public authority had carried out user surveys (Careborg Reference Careborg2012:66; Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:54). Some of the studied public authorities’ Easy Language online material was also often difficult to find and contained too little information to give the reader a sufficient grasp of the context (Careborg Reference Careborg2012:68–69; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:34). Thus the reader was also required to possess digital competences (Careborg Reference Careborg2012:69; Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:58; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014; Holmberg Reference Holmberg2018:55–56).

3.5 Group 4: Creating models for measuring text complexity

This group consisted of computer linguistic studies that intended to create models for measuring text complexity (n = 4). The papers were primarily written by the same three researchers and consisted of two articles (Falkenjack et al. Reference Falkenjack, Heimann Mühlenbock, Jönsson, Oepen, Hagen and Johannesse2013; Heimann Mühlenbock et al. Reference Heimann Mühlenbock, Johansson Kokkinakis, Liberg, Geijerstam, Wiksten Folkeryd, Jönsson, Kanebrant, Falkenjack and Megyesi2015), a doctoral thesis (Heimann Mühlenbock Reference Heimann Mühlenbock2013), and a licentiate thesis (Falkenjack Reference Falkenjack2018).

The papers in this group were all published in English, focused on written texts, and used the term ‘easy-to-read’, sometimes abbreviated as ‘ETR’ (Heimann Mühlenbock Reference Heimann Mühlenbock2013). Heimann Mühlenbock differentiated between ‘easy-to-read type’ texts and ‘ordinary type’ texts and provided the following definition: ‘broadly controlled natural language, … a subset of natural languages obtained by restricting the grammar and vocabulary in order to reduce or eliminate ambiguity and complexity’ (Reference Heimann Mühlenbock2013:22). Falkenjack contrasted the term with ‘regular texts’ and texts ‘written for a more typical readership’ (Reference Falkenjack2018:69). It is also observed that ‘easy-to-read texts’ of different genres could differ considerably from each other (Heimann Mühlenbock Reference Heimann Mühlenbock2013:129–143, 155, 160; Falkenjack Reference Falkenjack2018:69). All the papers in this group used the LäSBarTFootnote 7 corpus as material, which includes texts of different genres. The mix of literature and informative text as studied material is unique in our study. In their article, Falkenjack and colleagues conceptualised ‘easy-to-read texts’ as LäSBarT corpus texts (Reference Falkenjack, Heimann Mühlenbock, Jönsson, Oepen, Hagen and Johannesse2013:10). This is slightly problematic, firstly as the fiction part of the corpus also included ordinary children’s fiction (Heimann Mühlenbock Reference Heimann Mühlenbock2013:182–184). Secondly, it remains uncertain how accessible the texts in the corpus that are labelled as lättläst really are, as they have not been evaluated by readers, an aspect also pointed out in the only paper of the other groups of our study that refers to the papers in Group 4 (Wengelin Reference Wengelin2015:4–5, 14).

In her doctoral thesis, Heimann Mühlenbock (Reference Heimann Mühlenbock2013) presents the SVIT language model as a tool for classifying texts into different levels of complexity. By combining analysis of the surface-level features used in earlier readability formulas for Swedish texts with analysis of deeper linguistic features,Footnote 8 the SVIT model has succeeded in more accurately classifying texts into different levels of complexity. A later study found that the model was accurate, as the results from reading tests for 8th grade students corresponded with the results from levelling the texts using the model (Heimann Mühlenbock et al. Reference Heimann Mühlenbock, Johansson Kokkinakis, Liberg, Geijerstam, Wiksten Folkeryd, Jönsson, Kanebrant, Falkenjack and Megyesi2015). Yet the problem of the text corpus’s connection to Easy Language remains.

Group 4 was the only group of papers that displayed an explicit intertextuality, through cross-referencing researchers and common references. As all the papers in this group focused on readability in order to create or further develop models for measuring text complexity, a common list of key references is natural. References are commonly made to Chall (Reference Chall1958), Björnsson (Reference Björnsson1968), Kincaid et al. (Reference Kincaid, Robert, Richard and Brad1975), Graesser et al. (Reference Graesser, McNamara and Kulikowich2011), and other contributors to readability research.

It was noted that there are different needs within the target group (Heimann Mühlenbock Reference Heimann Mühlenbock2013:18–20; Falkenjack Reference Falkenjack2018:55). Heimann Mühlenbock pointed out that there may be different reasons for reading difficulties, and the need for support may vary according to different diagnoses: ‘Persons with intellectual disabilities, and those suffering from autism, aphasia, or dyslexia, people who are deaf from childhood, the elderly and second-language learners all have their specific needs in terms of reading materials’ (Reference Heimann Mühlenbock2013:18–19). She refers to the intended readers using the plural form of target group, stating that ‘different target groups of readers experience dissimilar reading difficulties’ (Reference Heimann Mühlenbock2013:20).

4. Discussion

In this section we reflect on our method and the findings of our study. There are separate subsections for each of our research questions: Which terms are used to describe Easy Language? Is the target group described in different ways? Which ideologies, discourses, or values justify Easy Language? The last subsection presents the implications of our study for future research, practice, and policy.

4.1 Reflections on the method

The meta-narrative review proved to be a suitable method for our study. We were able to use our professional knowledge and networks to complete the systematic database search, as well as intuition and interpretation when analysing and describing our material – methods that enabled the sensemaking of heterogeneous and fragmented material.

Although the vast range of disciplines, methods, and aims in our material should be seen as an advantage and even a necessity, we admit that it complicated the comparison of studies and identification of intertextualities and similarities.

An unavoidable consequence of using intuitive methods is the irreplicable results. Although the account given in this article is supported by references to our material, admittedly, it is a crafted narrative. The material is multidisciplinary, but we collected it as linguists. For instance, we conducted a manual search in two linguistic conference publications for research on Easy Swedish, which added one article to our material. Other criteria might also have been selected for categorising the papers into comparable groups.

4.2 Terms and definitions

The Swedish word lättläst has been used to describe adapted texts since the 1960s, and as mentioned in Section 3.2, it has at times included adapted spoken language. The studied material in the papers included in this review was consistently written text, using the term lättläst (Easy to Read).Footnote 9 The terms lätt svenska (Easy Swedish) and lätt språk (Easy Language) were not used. Regarding this, we noted a difference between the academic papers in our material and the non-academic texts used as references (Appendix B), where these three terms were used, and additionally läsbarhet (readability) and begriplighet (comprehensibility). The term lätt språk is more frequently used in publications from Finland.Footnote 10

When conducting the systematic database search, we used the key words lättläst, lätt svenska (Easy Swedish), and lätt språk (Easy Language), but lättläst was the only fruitful one of these. Neither did we observe any use of lätt svenska or lätt språk in our collected material. However, we did observe the adjective lättläst in combination with both språk and svenska: lättläst språk and lättläst svenska (Piira Reference Piira2009; Rautoma Reference Rautoma2011; Careborg Reference Careborg2012; Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014; Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016; Arle Reference Arle2018; Lindberg Reference Lindberg2019). In some papers, lättläst språk was used when quoting official documents where the term is used, i.e. the Swedish translation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Careborg Reference Careborg2012:11) and the Finnish National Action Plan on the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Arle Reference Arle2018:9). We regard this as an example of the above-mentioned use of lättläst in a broader sense than written language alone. The matter is complicated, as this use of the term can be confusing for those new to the subject, who instinctively interpret läst as connected to the reading of text. It can also be seen as frustrating in a bilingual or international context, as it is easier to handle terms and expressions that translate literally or word by word to another language.

The exclusive use of lättläst, or the translation suggested by authors writing in English, ‘easy-to-read’– spelled with hyphens both as an adjective and as a noun (Falkenjack et al. Reference Falkenjack, Heimann Mühlenbock, Jönsson, Oepen, Hagen and Johannesse2013; Heimann Mühlenbock Reference Heimann Mühlenbock2013; Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2013; Falkenjack Reference Falkenjack2018) – as the only term in the research included in this study stands out in the emerging international research field of Easy Language. Studies of Easy German and Easy Finnish use the wider term ‘Easy Language’ or equivalents, which encompass both spoken and written language (e.g. Kulkki-Nieminen Reference Kulkki-Nieminen2010; Deilen & Schiffl Reference Deilen, Schiffl, Hansen-Schirra and Maaß2020; Gutermuth Reference Gutermuth2020; Maaß & Rink Reference Maaß and Rink2020).

As seen in Section 3, there is no agreement on a detailed definition of the term lättläst. Most definitions are limited to text – ‘text type’, ‘adapted text’, and ‘text format’ being the most frequent ones. It is also noteworthy that the definitions do not explicitly follow discipline boundaries. In some cases, no clear definition is provided, giving the impression that the meaning of the term is considered self-evident (Falkenjack et al. Reference Falkenjack, Heimann Mühlenbock, Jönsson, Oepen, Hagen and Johannesse2013; Falkenjack Reference Falkenjack2018; Engblom Reference Engblom2019).

The expression lättläst is not exclusively used in connection to texts written in Easy Swedish that target struggling readers. The same word can be used in a more general sense to refer to texts that are easy from a personal perspective or easily read by the average reader. In our systematic literature search for papers on Easy Language, the keyword lättläst repeatedly led us to researchers from various disciplines who used this expression to describe their popular science works.

If spoken language is included in the term lättläst, definitions such as ‘text type’ or ‘adapted text’ seem too narrow. When studying the concept as a whole, we prefer the less narrow definition given by Heimann Mühlenbock: ‘broadly controlled natural language, … a subset of natural languages obtained by restricting the grammar and vocabulary in order to reduce or eliminate ambiguity and complexity’ (Reference Heimann Mühlenbock2013:22). It could also be argued that this definition covers the term ‘Easy Language’ (lätt språk), as it is not limited to texts. Nevertheless, we admit that this definition would need some addition if it were to serve all the papers in our study, as structure, layout, selection of content, and publishing context are often seen as part of the concept.

4.3 Descriptions of the target group

Our study indicates general agreement that the target group for Easy Language is heterogeneous, and its members have varying needs (Section 3). However, these statements are not results of the conducted studies, but based on references, often to non-academic contexts. Subgroups within the target group are often listed and accompanied by examples of difficulties or diagnoses. The target group is sometimes divided into two main subgroups: one primary or original group, consisting of people with an intellectual disability, and one secondary or novel group, consisting of other subgroups.Footnote 11

Although the target group is commonly considered heterogeneous, views on the readers and the conceptualised function of Easy Language texts differ. The researchers in Group 2, who focused on fiction, and those in Group 3, who focused on informative texts, had different perspectives on both the relationship between the reader and text, and the reading process.

Group 3, which focused on the characteristics of the texts, critically examined the ability of the texts to supply information, and the conceptualised problem was whether the texts were accessible enough and the readers received the intended information. If communication failed, it was because the texts were not accessible enough (Section 3.4).

The researchers in Group 2, mainly representing pedagogics and literature, examined whether the texts could provide a valuable reading experience, and the conceptualised problem was pedagogical utility – whether the intended readers could (or should) benefit from Easy Language books to develop desired skills. In this case, the increasing number of such books being published and marketed to young readers in general was criticised. Communication was seen as failing if the readers did not obtain a satisfactory reading experience or the text was not demanding enough – the reason being that the reader was wrong for the text (Section 3.3).

In Group 4, which focused on developing computer linguistic models for measuring text complexity, a mentioned motive was that readers and teachers should be able to estimate whether a certain text is suitable for a reader, and thereby prevent readers attempting and failing to read texts that are too difficult for them (Falkenjack et al. Reference Falkenjack, Heimann Mühlenbock, Jönsson, Oepen, Hagen and Johannesse2013:2; Heimann Mühlenbock et al. Reference Heimann Mühlenbock, Johansson Kokkinakis, Liberg, Geijerstam, Wiksten Folkeryd, Jönsson, Kanebrant, Falkenjack and Megyesi2015:257). These same measurement tools could be used by the above-mentioned critics and allow them to reserve the easier texts for a specific group of readers.

As shown in Section 3, Groups 1, 3, and 4 all discussed that it might be impossible to write one text that is ideal for all struggling readers. A consequence of this is that different subgroups need texts to be adapted in different ways, and texts should therefore be adapted according to the needs of the intended reader. However, the prioritisation of subgroups in terms of mass publications or public authority texts has been disputed (e.g. Careborg Reference Careborg2012:66; Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014:30). This discussion is more noticeable outside the academic context, where it has been the topic of journalistic articles and debated by practitioners working with Easy Swedish. One example of this is a debate on the prioritisation and the actual needs of different groups in the popular science magazine Språktidningen in 2011 (Bohman & Tronbacke Reference Bohman and Tronbacke2011; Englund Hjalmarsson & Jenevall Reference Englund Hjalmarsson and Jenevall2011:89).

As seen in Section 3, many papers state that Easy Language texts are seldom or never adapted for one specific subgroup. On the contrary, as noted in the same section, public authorities tend to produce one single text version, which is aimed at all readers in need of easier texts. As public authorities seldom or never carry out reception surveys, the actual comprehensibility of their texts remains unknown.

The material cited different opinions on Easy Language literature. The critical voices often denounced Easy Language books as skeletal or meagre (Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2013:68; Lindberg Reference Lindberg2019:1, 5, 78). This was partly supported by both the researchers and informants in Group 2 (Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2018:48–49). In contrast to this, other studies showed that Easy Language novels were appreciated by interviewed readers (Rautoma Reference Rautoma2011; Engblom Reference Engblom2019; Lindberg Reference Lindberg2019). The novels created an enjoyable reading experience and were not considered meagre by the readers. However, a study on health information texts provided different results. In a text comprehension test, the informants did not perform significantly better when reading Easy Language versions than when reading more difficult ‘authentic’ texts (Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2013:79).

4.4 Ideological and economic aspects of Easy Language

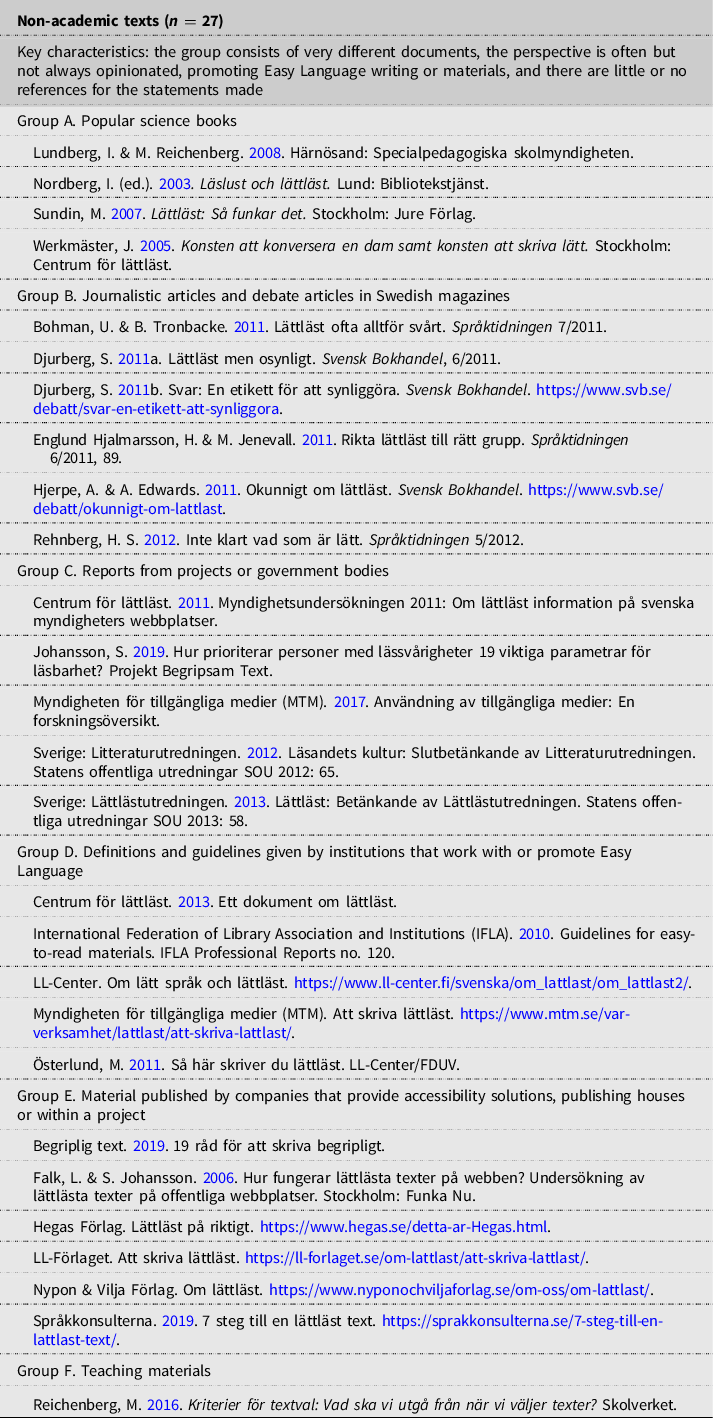

We repeatedly observed democratic discourses and increased legislation as the momentum or justification for the publication of Easy Language texts in our material, as mentioned in the previous section. These processes in society have also brought about an interest in research, as all the papers in our study were published after these events, which is illustrated by the timeline in Appendix C.

Reports on deteriorating reading skills such as PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) and PIAAC (the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies) were repeatedly mentioned in our material.Footnote 12 In some cases, such reports were used to describe the size of the target group or literacy skills of the population (e.g. Careborg Reference Careborg2012:7; Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021:543), in other cases as part of an explanation for the increasing number of published Easy Language books (Nordenstam & Olin-Scheller Reference Nordenstam and Olin-Scheller2018:47).

There is consensus that weak readers are entitled to texts they can read, and that Easy Language is a means to ensure this. The right to information is not just an ideological opinion: it is also stated in the legislation (Sections 3.4, 3.2). However, the practical consequences of this are regarded somewhat differently according to which genre of text is discussed or used as material. As noted in Section 4.3, the researchers who focused on literature discussed whether these books qualified as good literature, and whether they should be reserved for the weakest readers while others should read more demanding literature. In contrast, the researchers who studied informative texts discussed whether these texts were easy enough and questioned whether weak readers would be able to access the intended content.

Financial aspects play a certain part when public authorities produce Easy Language texts. As shown in Section 3.4, public authorities seldom examine whether the information is comprehended by the intended readers. Hence the varying needs of readers are not met, and the responsibility of receiving the required information is placed upon the readers.

As Easy Language books are mostly published by publishing companies, there is an economic interest to increase sales figures, regardless of whether or not the consumers need such texts. This could be seen as a background factor to the reactions in some of the papers in Group 2, which expressed concerns that Easy Language books would be read by readers that could read more difficult books (Section 3.3). But to reserve Easy Language literature for weak readers in a very explicit manner would be contradictory to the ideological discourse seen in Section 3.2, which claims that readers in need of Easy Language should be seen as equal to others. Our material also showed that some readers with intellectual disabilities did not want to be associated with Easy Language, as they seemed to find such texts stigmatising (Holmberg Reference Holmberg2018:40, 55). This is supported by similar results that have been presented internationally (e.g. Gutermuth Reference Gutermuth2020).

4.5 Conceptualisations of Easy Language

The conceptualisation of Easy Language was closely linked to the studied material or genre, and to the research focus of the studies. Most papers focused on either informative texts or literature, the exceptions being the papers in Group 4 and the review article we placed in Group 1. The computer linguistic papers in Group 4 studied material of mixed genres, consisting of both literature and informative text. This group focused on developing methods for identifying ‘easy-to-read texts’, regardless of genre. The aims of the papers in the other groups were more connected to a specific genre. The researchers from the disciplines of literary studies and pedagogics in Group 2 focused on literature. They were interested in the reading experience, and in some cases included readability and comprehensibility. The role and effect of Easy Language literature – not the concept itself – was regarded as a research problem. The material of the studies was often limited, and only a few titles were allowed to represent the whole category of Easy Language literature. Still, general conclusions were drawn instead of perceiving these as case studies.

The papers in Groups 1 and 3 – into which we placed the linguists of our study along with authors representing various other disciplines – had a more querying nature regarding courses of action to achieve accessibility. They examined whether it is possible to construct texts that in fact are easy to read, and guidelines for writing such texts. Whereas the focus varied in Group 1, all the papers in Group 3 studied informative text. Some papers in these two groups questioned whether texts labelled as lättläst were in fact comprehensible to the intended reader. Hence, although the conceptualisations of the term as a whole complied, the perspectives differed slightly depending on the research context.

The guidelines for writing Easy Language texts have been criticised for being contradictory, focusing too much on surface-level text features, and misinterpreting the research on which they are based (Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014; Wengelin Reference Wengelin2015). Moreover, published Easy Language texts and books do not always comply with the guidelines (Forsberg Reference Forsberg, Persson and Johansson2014; Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016). As Bohman (Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021) pointed out, Easy Language texts in different genres differ from each other, but the guidelines usually do not, even though they might be applied differently.

Concerning the usage and conceptualisation of terminology, a certain ambivalence was noticeable among the researchers in our material. A comparison across the groups showed tendencies of vagueness when defining the term, describing the texts, and referencing, which could be regarded as a consequence of the lack of consensus and research tradition in the field of Easy Swedish. In one paper, we noted the term ‘easy-to-read’ in inverted commas, which could indicate hesitation regarding whether the term can be used in an academic context (Heimann Mühlenbock Reference Heimann Mühlenbock2013:53). This apparent uncertainty is understandable, as there is no research tradition on which to lean.

Another phenomenon that could be regarded as a symptom of the lack of a research tradition is little or no conscious dialogue and intertextuality among the authors of our study. Like Chinn & Homeyard (Reference Chinn and Homeyard2017:4), we did not find much cross-referencing between studies and struggled to identify common research traditions or ‘foundational studies’. As shown in Section 4.2, authors often omitted mentioning other research on Easy Swedish, giving the impression that they were not aware of it. This could at least in part be explained by the contemporaneousness of most of the research, as illustrated by the timeline in Appendix C. Alternatively, this could be because the researchers did not consider the work in other disciplines relevant. However, as research on Easy Swedish has remained scarce, it is not surprising that non-academic references make up a substantial part of the references in our material, in particular concerning the definitions and descriptions of Easy Language. The equalisation of source type that we noted in the academic papers could, however, be problematic. It creates the risk of intertextuality or reference chains in future research and practice based on originally non-academic – and potentially incorrect – sources. To prevent this, we stress the necessity of scrutinising and clearly describing the used references, clarifying or separating academic sources from non-academic ones, and differentiating original sources from second-hand ones.

Some common references were visible within the borders of the disciplines: Björnsson (Reference Björnsson1968) in linguistics, pedagogics, and translation studies (Lindberg, Rautoma, Reichenberg, Wengelin), and Graves & Philippot (Reference Graves and Philippot2002) among pedagogics (Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2013; Lindberg Reference Lindberg2019). The papers were quite contemporaneous (illustrated by the timeline in Appendix C) and there were no visible paradigm shifts in our material.

The studies also lacked joint complexity measurements or characteristic-analysing models for the texts used in the studies, which makes comparing the results difficult. The only text information repeatedly provided was the LIX value, but even the authors who used LIXFootnote 13 as a tool for describing the texts pointed out the limitations of the model (i.e. Rautoma Reference Rautoma2011; Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2013:96, 73–74; Lindberg Reference Lindberg2019:5, 16–17). As shown in Section 3, Easy Language texts can differ greatly from one another in terms of text complexity, content, and style. A successful comparison of the studies would therefore require having access to the texts used in the studies. The use of LIX as the only common analytical description tool is also problematic because of the formula’s limitations, as it is based on word length and sentence length even though many co-operating variables affect the readability and comprehensibility of a text (e.g. Heimann Mühlenbock Reference Heimann Mühlenbock2013:5, 7, 27, 32, 48; Wengelin Reference Wengelin2015:3–4). Interestingly, in our material, the LIX model was favoured over the more accurate text complexity model SVIFT by Heimann Mühlenbock, including in papers published after this model was introduced in 2013.

According to a wide and simultaneously vague definition of lättläst, the term describes texts written for and understood by struggling readers. The term is commonly associated with a specific group of readers (e.g. Bornhöft Reference Bornhöft2016:3; Falkenjack Reference Falkenjack2018:69; Bohman Reference Bohman, Lindholm and Vanhatalo2021:535). Giving a more exact definition of terms such as Easy to Read and Easy Language is challenging for several reasons. The concept can be used for texts of different levels of comprehensibility or seen to include different kinds of text characteristics, such as choice of content and publishing context. The definitions differ within disciplines, as well as in different genres or different areas of practical usage.

4.6 Implications for future research and practice

We encourage future researchers to make use of the research conducted in other disciplines. In our material, we observed a reluctance to use references outside the authors’ own discipline. This was even the case in one of the linguistic papers in our material that stressed that interdisciplinary research was a necessity (Domeij & Spetz Reference Domeij, Spetz, Lindström, Henricson, Huhtala, Kukkonen, Lehti-Eklund and Lindholm2014:59). We emphasise that research on Easy Language could benefit from a combination of methodology and perspectives, allowing researchers from different disciplines to identify the overall research field of Easy Language. An increased dialogue across disciplines could bring order to the diversity and complexity of research contributions. In the papers we selected for our study, we identified several adjacent fields of research, such as Plain Language, comprehensibility, and readability. Future researchers might benefit from studies within these fields, depending on their focus.

We stress the importance of research results being effectively communicated to policymakers and practitioners. We also call for studies that combine the computer linguistic methods of Group 4 with reception studies, using the concepts of Group 3 as a starting point (Reichenberg Reference Reichenberg2000, Reference Reichenberg2013).

The focus of the research included in this review has been on Swedish written texts, and the definitions and descriptions of Easy Swedish have been based on practical work in the field. The inclusion of different modalities would have given us different definitions for spoken Easy Language, written Easy Language, and signed Easy Language. The purpose of all these would be the same – Accessible Communication – but when adding the question of how this goal is achieved, the definitions begin to differ. Another possible approach could be a comparison of definitions and descriptions based on research on Easy Language in an international context. As the present study focused on conceptualisations of Easy Language through definitions, descriptions, apprehensions of the target group, and justification rhetoric, a more extensive concept analysis was excluded. Such an analysis could, however, constitute a valuable addition to the research field of Easy Swedish.

5. Conclusions

We initiated this review with reference to the extensive complaints about the lack of research on Easy Swedish repeatedly expressed in the papers of our study. We were surprised by how many papers ultimately met our criteria for inclusion.

In our study, we found no universal definition of Easy Language. The term used in the academic material was lättläst, and the research focused on written language. There was no agreement on a detailed definition of this term either: a general conceptualisation of the term was that these texts are, or should be, comprehensible for struggling readers. A definition that encompassed all interpretations would be vague, whereas a more specific definition could result in non-concurrence. Most authors of our material might agree with the definition given by Heimann Mühlenbock (Reference Heimann Mühlenbock2013): ‘a subset of natural languages obtained by restricting the grammar and vocabulary in order to reduce or eliminate ambiguity and complexity’. However, this definition could be problematic for some, as it excludes publishing context and selection of content. An advantage is that it is not limited to text.

Our results show general agreement on the heterogeneity of the target group and the existence of several subgroups. This is often regarded as a problem, as the same text presumably does not fulfil the different needs of various groups, or if aiming to do so, fails to fulfil any specific subgroup’s needs. Our results also show that changes in society, legislation, and international conventions underpin the conceptualisations related to Easy Language. At times, the ideologies and discourses in our material were somewhat contradictory.

Easy Swedish is an emerging research field, and studies to date present great heterogeneity in terms of discipline, methodology, aims and focus, and the conceptualisation of Easy Language. Our results show controversy arising from different perspectives on reading as well as the breadth of the concept. The conceptualisation of Easy Language varies depending on the aims, discipline, and studied material, demanding conceptual flexibility within the research field.

Acknowledgements

The workload was equally divided between the authors in all the phases of producing this article, including both the search, analysis, and writing phases. The article is part of the ‘Easy Swedish in Finland’ research project, financed by the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland (SLS). Additional funding was granted by Nylands Nation and the Swedish Cultural Foundation in Finland.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Appendix A: Grouping the material

Appendix B: Non-academic texts referred to in the material for definitions and descriptions of Easy Language

Appendix C: Timeline showing the publication of the papers included in this study and related legislation and reports