With the death of their creator and principal performer, Mozart's piano concertos rapidly fell into oblivion.Footnote 1 Although they became available in print – most of them for the first time – through André's collected edition in the early 1800s, none but the two works in minor keys survived on the concert stage. The continued appeal of the concertos K466 in D minor and K491 in C minor rested in particular on their the dark, demonic and tragic character – features that resonated strongly with the romantic imagination. Significantly, Beethoven, who shaped the nineteenth-century perception of eighteenth-century music like no other, programmed both as a soloist. Additionally, these two concertos – and to a lesser extent also Mozart's concertos in G Major, K453,Footnote 2 and in B-flat major, K595Footnote 3 – sparked off his own compositions. The opening movement of his C minor concerto clearly recalls the model of Mozart's K491,Footnote 4 a work which he held in particular esteem. As Johann Baptist Cramer's widow informs us, he exclaimed ecstatically upon hearing a performance of K491: “Cramer, Cramer! We shall never be able to do anything like that!” (Cramer! Cramer! Wir werden niemals im Stande sein, etwas Ähnliches zu machen!).Footnote 5 While Beethoven undoubtedly performed Mozart's concertos with his own cadenzas, he wrote out two cadenzas to K466 (WoO 58). As early biographies suggest, he may even have played this concerto in 1795 at a benefit concert for Mozart's widow Constanze.Footnote 6 Moreover, the D minor concerto shared tantalizing affinities with Don Giovanni and the unfinished Requiem (in the same key), which were at the core of the romantic conception of Mozart.Footnote 7 As an ominous prelude to an ‘absent’ piece, the incomplete D minor Fantasia K387 evokes romantic ideas of the fragment.Footnote 8

Conflicting Testimonies

Imbued with the aura of this D minor complex, K466 was the one concerto from Mozart's pen that enjoyed fairly regular performances throughout the nineteenth century. As Carl Reinecke sarcastically observed, if any Mozart concerto was heard in the concert hall, the odds were 99 to 1 in favour of K466.Footnote 9 Clara Schumann played no small part in shaping this trend, as she had become one of the leading interpreters of Mozart's D minor concerto in the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1891, having performed it for over three decades, she shared her cadenzas with the wider world, their publication coinciding with the centenary of Mozart's death.Footnote 10 As she studied the second proofs from the publisher Rieter-Biedermann, she was struck by an uncanny discovery. The shock of a ‘doppelgänger’ experience, in keeping with the concerto's haunting D minor qualities, reverberated viscerally in her diary entry on Michaelmas day of 1891:

Today I received the second proofs of the cadenzas to Mozart's D minor concerto, which, after much encouragement by my children, I wished to publish at long last. I have always had the illusion that no more than 8–10 bars of the first cadenza were by Brahms. I had discussed it with Johannes once, and he thought I should not be concerned about it. Today, however, I thought I should look up Brahms's cadenza, which I have owned for a long time, and I realized to my great horror that I had used many things from his cadenza and that I could not possibly proceed with the publication of these cadenzas (the first one in particular). I immediately wrote to Johannes about this matter.

How on earth could this have happened to me! Over the years, the cadenza has become second nature to me so that I could no longer remember what was written by myself or by him – except for a single passage of special beauty that I had intended to mark with [his initials] JB, anyway.Footnote 11

Schumann immediately shared her distress with Brahms:

Unfortunately, I do not feel well enough to write to you in my own hand; but I have to tell you something that exercises me and about which I could be very keen to receive your response as soon as possible. As you know, for the D minor concerto of Mozart I have always played my own cadenzas; to this end you had once given me permission to use some material from the cadenza made by you. For years I had been asked to publish the cadenzas, which I decided to do this summer, since I no longer play in public. Over time the cadenzas had become second nature to meFootnote 12 to the extent that – with the exception of a particularly beautiful passage (which I intended to mark with J.B.) – I no longer knew that I had taken over a lot more from you. Today, as I receive the second proofs from Rieter, I have the fortunate idea to trace our old cadenza. I then realize with horror that I would have nearly adorned myself with borrowed plumes. – I am now in a dreadful predicament concerning Rieter and know of only two options: either I withdraw my cadenzas, provided, of course, that the matter remains between us, or you permit to state in the title: ‘with partial use of a cadenza by Johannes Brahms’. If you accept the latter proposal, would you mind formulating the title in the correct style? It is terrible that this could have happened to somebody as scrupulous as me! – Unfortunately, I am still so poorly that I cannot resume my lessons nor do anything else at all. – For three weeks I have been tormented by aural apparitions in my head day and night so that I am often in a state of complete despair. The doctors declared it to be a purely nervous condition and they consoled me that it will pass away, which I have to reason to hope, because it had vanished a few times for short periods. I conclude with the repeated plea to send a speedy reply to

Your old Clara who greets you lovingly.Footnote 13

Read side by side, these two statements (written within a matter of hours) appear equivocal, if not duplicitous. Schumann confessed to Brahms that she was so distressed over her discovery that she had to dictate the letter. Yet, this did not keep her from making an entry into her diary. There is more to be drawn out of this ambiguity. Schumann was evidently thunderstruck by the visual evidence of similarity between Brahms's cadenza and her own. This déja-vu found its aural equivalent in the way she described her medical condition to Brahms. An ailment that might well be classed as tinnitus is articulated in a mixed metaphor that blends different modes of sense perception: The term ‘Gehörserscheinungen’ (literally: auditory apparitions) evokes an uncanny throwback listening experience that is at once real and unreal. The multisensory fusion of hearing and seeing is paralleled by a blending of mental and physical processes. Both in her diary and in the letter to Brahms, Schumann attributes the question of ownership of the troublesome cadenza to the bodily dimension of the creative process.Footnote 14 In the course of repeat performances, she suggests, the cadenza had gradually become second nature to her to the extent that it had become incorporated into her performing body. As the metaphor ‘in Fleisch und Blut übergegangen’ suggests, the conceptual category of a musical ‘work’ had been morphed into her ‘flesh and blood’.

The intriguing blending of visual, aural, mental and physical categories that emerges from these two statements opens up fruitful avenues of enquiry with regard to the multifaceted nature of Schumann's creative process. The crisis of 29 September 1891 continued to play on Schumann's mind. As she was agonizing over her perceived intellectual theft from her close friend, she outlined to Brahms two possible paths forward. Either she would abstain from the publication of the cadenzas altogether, at the risk of alienating her publisher. Or she would own up to her ‘borrowings’ with the public declaration that her cadenzas had made ‘partial use of a cadenza by Johannes Brahms’. Brahms proved deaf to both proposals. His response to Schumann shows no desire to claim authorship of the cadenzas in question:

Dear Clara,

I beg you very cordially to let the cadenzas go out into the world under your name without any further ado.

Even the tiniest J.B. would only look peculiar; it is really not worth the effort, and I could show you several more recent works, in which there is more by me than a whole cadenza! But in turn I would duly have to mark some of my best melodies as: ‘Originally by Cl. Sch.! – For when I think of myself, nothing reasonable or even beautiful would come to mind. I owe you more melodies than you could take passages of suchlike from me. … But regarding the cadenzas, you will certainly and easily calm down?Footnote 15

Against Brahms's intention, Schumann was more alarmed than assured by the emphatic generosity of his letter. She may have wondered why her friend was so eager to dissociate himself from the cadenza. After all, his input in the printed score could be understood as evidence of the lasting artistic collaboration and friendship between him and Schumann. Brahms strikes an uncomfortably patronizing note – trivializing Schumann's scruples without actually acquitting her of plagiarism. In this context it was cold comfort that Brahms casually confessed his (unspecified) melodic borrowings from Schumann.

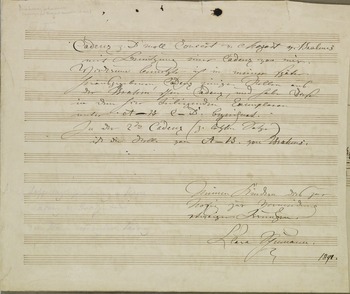

Brahms's equivocal letter provoked a surprisingly unapologetic response. Cutting through the Gordian knot, Schumann created a fait accompli. As if nothing had happened, her cadenzas were published in Leipzig by Rieter-Biedermann as her own work – without any qualification in the printed text.Footnote 16 In the same year, she appended a memorandum to her copy of Brahms's autograph of the cadenza in question, which turns the authorship question on its head (Fig. 1):

Cadenza for Mozart's D minor concerto by Brahms, with use of a cadenza of mine.

In my cadenza that was published later I in turn used some passages from Brahms's cadenza and have labelled them in the enclosed copies as A-B and C-D.

In the second cadenza (for the final movement) the passage A-B is by Brahms.

Memorandum for my children to avoid any potential misunderstanding.

Clara Schumann. 1891.Footnote 17

Fig. 1 Schumann's note to Brahms’ autograph of the cadenza to K466, mvt. i US-Wc (Whittall Foundation), ML 30.8b.B7 K45 Case. Reproduced with permission of the Library of Congress.

The inconsistencies, if not contradictions, between the correspondence and this memorandum caution against taking any of these documents at face value. Yet, to date, attempts to address the authorship question have suffered from a selective use of the evidence that reflected the specialisms of individual scholars. Editors of Brahms’ music have tended to privilege his authorship. While Eusebius Mandyczewski and Camilla Cai acknowledge some input by Clara Schumann (citing from the memorandum: ‘Mit Benutzung einer Kadenz von Clara Schumann’), the Complete Brahms Edition of 1927 assigns to it the opus number WoO 114, giving the impression that this was a stand-alone version ‘letzter Hand’.Footnote 18 On the other hand, Schumann's first biographer Berthold Litzmann and other champions of her music regard the memorandum to her children as authoritative.Footnote 19

The authorship question is further complicated by the discovery of a ‘genuine’ cadenza for K466 by Brahms, found by Johannes Müller in the estate of Kurt Taut, former librarian of the Musikbibliothek Peters. In his first edition and critical assessment, Paul Badura-Skoda praises this composition above and beyond Brahms's other cadenzas for concertos by Mozart and Beethoven (WoO posth. 12 for Op. 58).Footnote 20 By comparison, Badura-Skoda ascribed what he considered to be the inferior quality of Schumann's cadenzas for Mozart's C minor concerto (WoO posth. 15 for K419), which are preserved in Schumann's papers as well,Footnote 21 to her poor taste. Freed from the ‘shortcomings and occasional insipidities’ (‘Unzulänglichkeiten und gelegentliche Geschmacklosigkeiten’) that he ascribed to Schumann's bad influence, the ‘genuine’ cadenza is praised for being much closer to Mozart's own style.Footnote 22 At its heart, the critical appraisal of the newly discovered cadenza is connected to an underlying unease about contested or ambivalent authorship that also emerges from the apparently conflicting statements by Brahms and Schumann about the other cadenzas for Mozart's D minor concerto.

This article challenges musicologists’ fixation on author attribution. Rather than using the testimonies of the sources to settle the question of authorship, I will use this very question as a vantage point for opening out onto a wider perspective: the degree to which the concerto in general, and the cadenza in particular, was a place to display the performative and compositional creativity of the artist. In the later part of the nineteenth century, as Angela Mace suggests, ‘composers such as Johannes Brahms and Clara Schumann’ would ‘develop the concept of the cadenza even further’ than their early nineteenth-century counterparts ‘in the direction of the fully compositional repetition in their own cadenzas to Beethoven's Op. 58’.Footnote 23 In the case of the cadenzas for K466, at least, the creative process was more collaborative than single-authored, and more open-ended than definitive. Conscious that both texted and untexted knowledge played a role in the evolution of their cadenzas for K466 (and for nineteenth-century cadenzas on the whole), I consider the extent to which their creative input was informed by Schumann's and Brahms's earlier performance history of these cadenzas, knowledge that had been stored in the minds and bodies of the musicians rather than on paper.

Chronology

In order to answer this question, it will be necessary to establish a sequence of events between two Mozart centenaries: A performance of a cadenza for K466 by Brahms in 1856 and Schumann's publication of the cadenzas in 1891. Chronologically, at least, Brahms's cadenza came first. On invitation from the Hamburger Musikverein and its director Georg Dietrich Otten, he played Mozart's D minor concerto, with his own cadenzas, on the eve of the centenary of the composer's birth (26 January 1856).Footnote 24 According to Brahms's biographer Kalbeck, attendance was poor, and the audience at best was indifferent.Footnote 25 The critic of the local newspaper Der Freischütz took issue with the anachronistic style of the cadenzas (‘neustylig’).Footnote 26 The underwhelming reception of Brahms's performance and his cadenzas may have kept the young pianist from programming K466 ever again.

Schumann's debut performance of the work followed a year later. Her diary noted that she played Brahms's cadenzas, albeit not to her satisfaction. While she was pleased with the performance overall, she regretted losing her calm and composure in the cadenzas: ‘I played very well, but Johannes's beautiful cadenzas did not turn out well, I played them too fretfully and timidly, about which I was very sorry.’Footnote 27 Unfortunately, no cadenza of this period has come down to us in notated form. Ludwig Sémerjian recently suggested that Schumann's earliest surviving autograph score (which is generally dated to the late 1870s) had been written already in 1855 in preparation for a planned concert in Leipzig that had to be cancelled because of Robert's death;Footnote 28 yet this early dating is implausible.Footnote 29 After all, Schumann's account of 1857 explicitly acknowledges that she played cadenzas by Brahms – likely, as Camila Cai suggests,Footnote 30 either from Brahms's own autograph score (now lost)Footnote 31 or a copy thereof (also lost). This hypothetical source is referred to here as [JB1]. At this stage, Brahms could have easily parted from this text, since he did not require it for any further performances of K466. Schumann, on the other hand, incorporated the concerto into her repertoire, playing it half a dozen times, and to much greater critical acclaim, over the course of the next two years (Table 1). Unlike Brahms, she garnered praise particularly for the stylishness of the cadenzas (which were interpreted to be of her own creation). Following the performance in Aachen (20 October 1859), the critic of Echo der Gegenwart praised Schumann's ‘brilliant cadenzas … of which the one inserted into the final movement in particular was stylistically remarkable’.Footnote 32

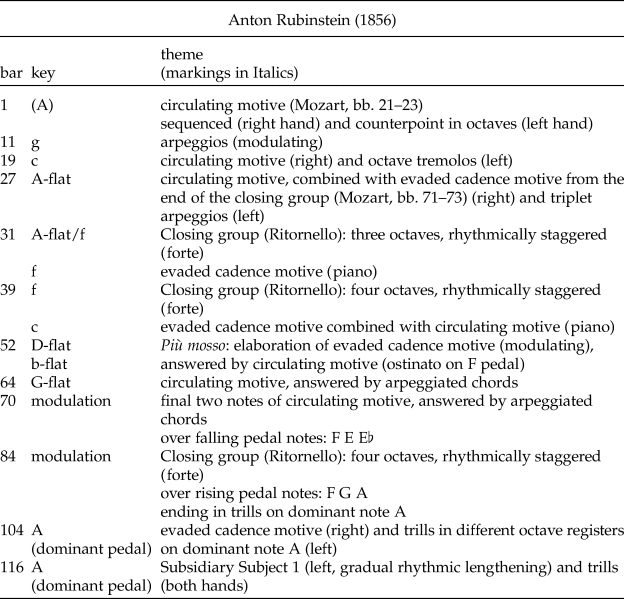

Table 1 Johannes Brahms and Clara Schumann: Concert performances of K466 and musical sources of their cadenzas

Clara Schumann's performances are listed according to Zwickau, Robert-Schumann-Haus, Archiv-Nr. 10463-A3, Nr. 364

Manuscript sources:

JB2 Washington, Library of Congress, Music Division, Whittall Foundation, ML 30.8b.B7 K45 Case: Johannes Brahms, autograph sketch of cadenza for the first movement of Mozart, K.466 (1878)

CS2 Washington, Library of Congress, Music Division, Whittall Foundation, ML 30.8b.S37: Clara Schumann, autograph sketch of cadenzas for the first and third movements of Mozart, K.466 (1878)

CS3 Washington, Library of Congress, Music Division, Whittall Foundation, ML 30.8b.B7 K45 Case: Clara Schumann, autograph of cadenzas for the first and third movements of Mozart, K.466 (1891), as submitted to the publisher

Detailed source descriptions in Camilla Cai (ed.), Johannes Brahms: Klavierwerke ohne Opuszahl, Brahms Werke, iii.7 (Munich: Henle, 2007), 216f.

While nineteenth-century performers increasingly fell back on pre-composed cadenzas (including their own),Footnote 33 they usually played these from memory. This new trend, which was frowned upon by pianists and pedagogues of the older generation, moved distinctively away from improvisation toward memorization.Footnote 34 Clara Schumann, who showed a natural talent for memorizing music from an early age,Footnote 35 promoted this practice in her own concerts. As early as 1837, she performed Beethoven's ‘Appassionata’ sonata, Op. 57, from memoryFootnote 36 – which scandalized Bettina von Arnim, who, having fully internalized the sexism of her age, berated the ‘presumption’ to play without a score (‘und nun ohne Noten!’).Footnote 37

In the performance context of a concerto, memorization was especially paramount during the cadenza, which was (in the post-Beethoven era at least) predetermined by a notated musical text of some sort. Even when soloists adopted pre-composed cadenzas, they honoured the older improvisatory practice by creating a simulacrum thereof in the concert hall. Yet, over time, even appearances can harden into something more substantial. Without recourse to a written score, a fully composed cadenza, too, would gradually have been transformed under the creative hands and minds of a skilled performer: from little tweaks and flourishes, to cuts, substitutions or interpolations of whole (fully or partially improvised) sections. When soloists developed, through repeated performances, their own performance tradition with a relative degree of fixity, the cadenzas – as embodied performances – were committed to body memory rather than cognitive memory or the score (the visual representation of a text).Footnote 38

Between January 1857 and October 1859, Schumann programmed K466 no fewer than seven times (Table 1). By virtue of frequent repetition, ‘her’ rendition of the cadenza is likely to have assumed a relatively fixed embodied form. When she took Mozart's D minor concerto to the stage again nearly a decade later (London, 5 March 1868), her muscle memory may have been sufficiently ‘fresh’ to allow her to operate without a written record – be it Brahms's autograph or her own adaptation thereof in the score. In the act of playing, her fingers and her mind could have intuitively recalled how she used to play the cadenzas. This embodied trace of the ‘cadenza’ could then have served as a blueprint or creative springboard for an at least partly renewed take on the cadenzas during the tour to London in 1868.

After this concert, another ten years passed before Schumann was contracted to perform the D minor concerto again in Hamburg (26 September 1878). By that time her haptic and cognitive memory had apparently faded to the extent that it was necessary to return to the drawing board rather than the piano. Significantly, the earliest surviving written records of the cadenzas in question – the autographs by Brahms (JB2) and Schumann (CS2) – were produced exactly at this point in time. A notated text may have facilitated the attempt to reconstruct her own performance tradition of playing these cadenzas in the 1850s and 1860s, or to start again from scratch by plotting out the whole cadenzas on the paper.

As Schumann started preparing for the concert, she confided her domestic, physical and creative challenges to Brahms:

I have been here [in Frankfurt] for a few days, but in a hotel. We cannot move into the house before the end of the month, at least we cannot stay overnight there. But all the while I have been practising there, in my charming room, for Hamburg. I also had to prepare the cadenzas, which gave me a terrible headache, as I found it difficult to get into the right mood. I used a few passages from you – I hope you won't mind?

… I still have great pain in both arms and do not know how I should possibly be able to play in Hamburg. But especially on this occasion I could not get myself to cancel [the concert], except as a last resort.Footnote 39

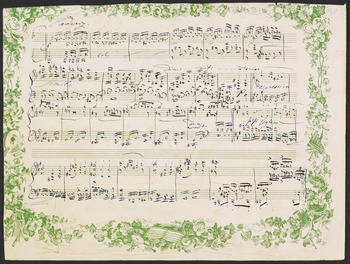

This letter is significant in several respects: Schumann mentions the cadenzas in the context of her piano practice. She describes the process of creating these cadenzas as ‘einrichten’ (arrange), which implies the recourse to some kind of model that had to be adapted or arranged. We can further infer from her suggestion to borrow a few passages from Brahms's cadenza that ‘his’ version of the cadenzas was available to her in some form. This written source could have been anything from rough scribblings to Brahms's own cadenza (the hypothetical [JB1], or one of Clara Schumann's adaptations thereof ([?CS1]). Whatever the status of the source she used, she was evidently driven by the ambition to create something substantially new or something that required meticulous pre-meditation. The notated score of her cadenzas – produced in fair copy (CS2, Fig. 2) – departed from her older performance practice of memorization to one of documentation, even though such documentation would have been receptive to influences from the past.Footnote 40

Fig. 2 Clara Schumann, autograph cadenza for K466, movement 1 (1878) (CS2). Washington, Library of Congress, Whittall Foundation, ML 30.8b.S37, p. 1. Reproduced with permission of the Library of Congress.

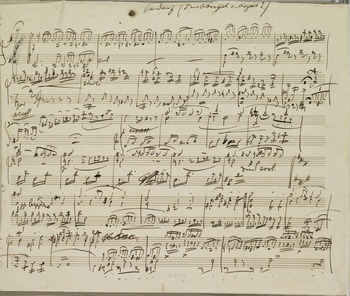

Brahms heard Clara Schumann's performance of K466 in Hamburg in 1878, two days before he conducted his Second Symphony at the same festival in celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the local Philharmonic Society.Footnote 41 In all probability, Brahms's own copy of a cadenza to the first movement, which survives among Schumann's papers (JB2),Footnote 42 was written in the context of this performance. Notably, his autograph marks a shift from memorization to documentation. As the casual ductus of his hand suggests, it was not his intention to create a polished work (Fig. 3). More likely, he took active part in a collaborative creative process that was initiated and led by Schumann, who, unlike Brahms, had a vested interest in documenting this cadenza. In that scenario, we might conjecture that Brahms may have acted as a sounding board for Schumann's idea, jotting down her suggestions or perhaps even transcribing her pianistic explorations, and retouching or changing passages during the process of writing. Some passages that did not make it into Schumann's final reduction may have been discarded by both; or Schumann preferred her own version over the suggestions of her colleague. Paradoxically, it was the scruffy working manuscript (written in Brahms's hand) of Schumann's cadenza that entered the former's work catalogue as WoO posth. 14 and was first published as part of the Complete Brahms Edition in 1927.Footnote 43

Fig. 3 Johannes Brahms, autograph cadenza for K466, movement 1 (1878) (JB2) Washington, Library of Congress, Whittall Foundation, ML 30.8b.B7 K45 Case, p. 1. Reproduced with permission of the Library of Congress.

The brief historical episode of 1878 is indicative of the intricate nexus between ideas of authorship and issues of performance practice in the late nineteenth century that finds its premier outlet in the cadenza. This, in turn, allows us to develop fresh approaches to Clara Schumann's creativity as a performer and a composer. If the two manuscripts of the cadenzas to K466 by Schumann and Brahms were created in the spirit of artistic exchange, a substantial overlap between them is unsurprising. If Brahms had merely lent a helping hand to a creative process directed by Schumann, it seems natural that he would relinquish any authorship. When she eventually decided to publish her cadenzas in 1891 she would have encountered the scores from 1878 when the two musicians had attempted to work out the cadenza in writing. Over the course of Schumann's life, the primacy of a performance tradition that does not rely on notation had given way to one that called for documentation. During the intervening years, as Schumann continued to play K466 another seven times before 1887 (Table 1), she further assimilated the cadenzas into her haptic memory, making tweaks and changes as she went along, and thereby embodying a non-fixed version of the cadenzas that went beyond notated scores.

Embodied Creativity and the Boundaries of Philology

Even for performers such as Clara Schumann, who championed literal realizations of the musical score (Texttreue),Footnote 44 cadenzas permitted, invited and justified a personal, bodily engagement of an entirely different order to the literal execution of a musical text. As the chronological account of the cadenzas for K466 made clear, the notated score may at best have served as the initial point of reference or aide-memoire in such body- and performance-driven creative practices,. Nonetheless, during her experience as editor of her late husband's work,Footnote 45 Schumann had also internalized the principles of textual criticism which now came into play along with the embodied and distributed creativity that had governed the genesis of her cadenzas. As she was checking Rieter-Biedermann's galley proofs in 1891, Schumann became suddenly perceptive to the substantive parallels between her scores (CS2 and CS3)Footnote 46 and Brahms's (JB2). Up to that point, she had believed that the borrowings from Brahms amounted to no more than 8–10 bars (Diary, 29 September 1891). With both manuscripts in hand, however, she realized that her memory may have been playing tricks on her. In the tension between text and (embodied) act, she was troubled by this misapprehension which she attributed to her body: ‘How on earth could this have happened to me! Over the years, the cadenza has become second nature [i.e. my own flesh and blood] to me so that I could no longer remember what was written by myself or by him’.Footnote 47

Contrary to Schumann's statement, the misapprehension was less caused by her body memory than by her excessive fidelity to the authority of the notated text. Side by side, the two musical sources document extensive shared material. But since the creative process was fundamentally embodied (informed by Schumann's physical memory of earlier performances and her explorative playing on the piano), her experience should not have been discounted so readily. In such processes, physical, sensory and cognitive aspects are so closely intertwined that it is almost impossible to extricate any one strand from another, let alone prioritize one over the other. The cadenza cannot be reduced to a conceptual abstraction represented in musical notation.Footnote 48

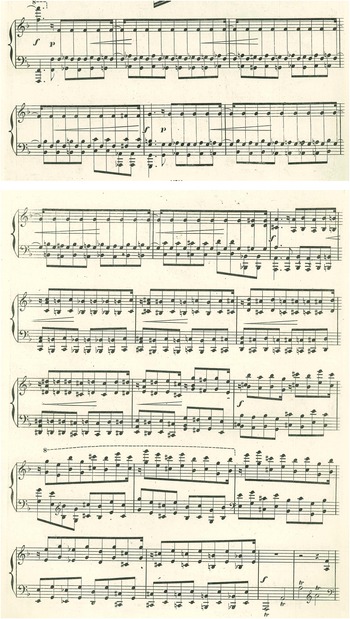

For this reason alone, the standard arsenal of textual criticism proved inadequate, if not outright deceptive, for the ‘editorial’ problem with which Schumann grappled in 1891. As the testimony of the notated texts conflicted with her own memory and sensory experience, her attempt to disentangle different creative and performative strands that had become inextricably intertwined over a period of three decades was doomed to fail. Schumann's annotations of the musical sources confirm the logical principle of deductive explosion. Ex falso quodlibet: from false premises, anything may follow, truth as well as error. There is a puzzling mismatch between passages marked as supposed ‘borrowings’ on Brahms's manuscript (JB2) and her ‘own’ cadenza (CS2/CS3). Schumann identified the first trace of borrowing (letter A, see the end of the second stave in Figure 3) exactly at the place where the two versions drift significantly apart (Ex. 1).Footnote 49 Up to that point (bar 11), both opening sections elaborate on the closing group, which features in the piano part of the first Solo section (K466, mvt. i, bars 153ff.)Footnote 50 and appears on either side of the cadenza (piano: bars 330ff., orchestra: bars 366ff.). In this section, Brahms's and Schumann's versions are almost identical, save for some dynamic nuances or minor retouchings (see Figs 2 and 3).Footnote 51 Upon closer inspection of the original sources, what Sémerjian describes as a ‘telling’ discrepancyFootnote 52 in bar 9 actually results from an almost identical shorthand notation in the 1878 autographs by Brahms (JB2) and Schumann (CS2) (Ex. 2). Neither is unequivocally clear about whether the Doppelgriffe fall on the strong or the weak semiquavers. The text Schumann submitted to her publisher Rieter-Biedermann (CS3) opted for the latter resolution (which subsequently made it into the printed edition). Brahms philologists since Mandyczewski, on the other hand, have settled for fuller chords on the strong semiquavers.Footnote 53 Since Brahms's notation is open to either reading, however, we can consider this to be an editorial preference, not a (demonstrable) compositional choice. Mandyczewski resolved the ambiguity by imposing what deemed him to be the most idiomatic writing for piano. According to Sémerjian, Brahms was ‘making a small correction [to Schumann's cadenza …] and this suggests Brahms was working off an existing text’.Footnote 54 The surviving sources do not support this interpretation, however.

Ex. 1 The first ‘borrowing’ identified by Clara Schumann; (a) JB2, bars 11–18; (b) CS2, bars 11–20

Ex. 2 Bar 9 in Schumann's and Brahms's autograph cadenzas for K466, mvt. i. (a) JB2 (b) CS2 and (c) CS3. Reproductions with permission of the Library of Congress.

Perversely, what Schumann had identified (letter A) as the first borrowing from Brahms actually marks the first major departure (Ex. 1). The syntactic function remains the same: both cadenzas segue into the second subject of the first solo section (the so-called solo exposition, K466, mvt. i, bars 128–143). But the two pianist-composers embark on very different tonal trajectories. Brahms leads from the dominant directly back to the tonic D minor. Schumann places Mozart's theme in B minor,Footnote 55 passing an F-sharp major seventh chord in transition to the new key area. In stark contrast to the borrowing marker, Schumann cannot have taken inspiration from Brahms here. Apart from the fact that the thematic material is Mozart's, her version is harmonically more enterprising. The key of B minor suggestively mirrors the relative major F, the key of the second subsidiary subject in Mozart's concerto. One is a minor third below (♮VI), the other a third above the tonic (III).

If Schumann had copied neither the modulation (which is absent in Brahms's score) nor the thematic material (which is Mozart's after all) from Brahms, one wonders why she marked it as a borrowing. As the notated scores do not provide an answer, it is far more likely that Schumann responded to a memory that was triggered by the sight of Brahms's manuscript. Perhaps she even relived her experience of listening to Brahms playing a cadenza back in 1856; her letter of 1891 speaks of ‘Gehörserscheinungen’ (sonic apparitions), after all.Footnote 56 In fact, the two musicians spent time together between Brahms's single performance of K466 and Schumanns's debut of the work in 1857. One can easily imagine that Brahms performed his cadenza for Schumann, and that the two discussed possible strategies. Perhaps they even took it in turns to elaborate individual ideas and experiment with them. This scenario, albeit hypothetical, would at least explain why she could make such a blatant misidentification of borrowings, which cannot be established through a philological comparison of the two notated scores. Arguably, therefore, Schumann's desire to acknowledge Brahms's input was prompted not by a déja-vu but by a déja-entendu, if not a déja-senti. The confusion arose because philology proved incapable of dealing with musical actions and experiences that had not left a paper trail in notated scores.

Schumann's reliance on memories played an even greater role in the cadenza to the third movement. In her own copy of the printed cadenzas of 1891, Schumann identified another borrowing from Brahms, which to date remains the unique trace of what Brahms's cadenza might have sounded like (Ex. 3).Footnote 57 No written record of Brahms's third-movement cadenza survives, as it is not contained in the manuscript of 1878 (JB2). Schumann's autograph of 1878 (CS2) did not preserve more than the opening seven bars of her cadenza to the final movement, which, after all, does not correspond to the fully executed text of 1891 (CS3). Moreover, the many ad hoc corrections in the latter source and the interpolation of an extended passage (bars 20–34) on a fold-out paste-overFootnote 58 suggest that Schumann did not work from an earlier notated score. Rather than writing down a fair copy of an earlier work (with cosmetic changes, as in the first-movement cadenza) for the publisher, she appeared to have created the cadenza as she went along, prompted by (cognitive and/or embodied) memories of her past performances of the cadenza.

Ex. 3 Clara Schumann, Cadenza to K466, mvt. iii (1891), bars 13–18

The absence of any corroborating evidence invites us to speculate that the borrowing from Brahms might well have been stored in Schumann's memory as well – perhaps as a recollection of how the former performed the passage in question, or how he advised her to alter her own performance.Footnote 59 Here, as in the cadenza to the first movement, the thematic material stems from Mozart's pen. In Schumann's arrangement of it, one may discern a distinctive Brahmsian flavour in the intricate interweaving of hands.

Returning to the first-movement cadenza, a similar scenario emerges. If the twin manuscripts of 1878 by Schumann and Brahms have anything in common, it is the imitative treatment of Mozart's second subsidiary subject at the upper sixth (CS2, bars 16–17; JB2, bars 13–14). Perhaps Brahms's influence went all the way back to Schumann's first performance of K466 in 1857, when the cadenzas had still been on Brahms's mind, too. In all other respects, Brahms's manuscript of 1878 presents itself as a revision of Schumann's score. As he had only ever played the cadenza in concert once in 1856, Brahms's recollection in 1891 would inevitably have been much fainter than Schumann's, who benefitted from repeat performances. But even if Brahms responded in written form to Schumann's notated score, it may well have conjured up memories of their earlier performances and exchanges in 1856.

The two autographs of 1878 diverge primarily with regard to the cadenza's tonal and formal structure (see Table 3).Footnote 60 While both versions eventually present the second subsidiary subject in the sharpened mediant F-sharp major (Schumann, bar 23; Brahms, bar 22), Schumann approaches it through B minor (bar 16), whereas Brahms returns to the tonic D minor (bar 13). Schumann reserves distinctively more space for virtuosic display (bars 30–52) before the arrival on the next thematic section, to which both composers assign a recitative-like character (Schumann, bar 53: Recitativo; Brahms, bar 36: ad lib. rezitativisch (poco largamente)). In this section, Brahms takes a more expansive approach. He dwells longer on the lyrical Solo lead-in (K466, mvt. i, bars 77ff.), which appears twice. He prefaces its presentation in A minor (bar 45), which is shared with Schumann's version (bar 53), with an additional statement in F-sharp minor (bar 36). Significantly, the two versions take different turns exactly at the point (Brahms, bar 36) where Schumann noted the second borrowing (letter B). On the way to the final bravura section, where the two versions reconverge, Brahms makes a detour via the first subsidiary subject (K466, bar 32 (Ritornello 1), bar 115 (Solo 1)). He develops the antiphonal two-bar motif into an ascending sequence (bar 56). Schumann, on the contrary, uses only the second half of this motif: the melodic line with its expressive octave leap and sighing figures forms the basis of a compact descending sequence (bar 69), with the sole purpose of reaching the next section without any unnecessary delay.

Considered together, the two cadenzas match both in their broad trajectory and in surface detail to an extent that points to a fruitful exchange of ideas between Brahms and Schumann.Footnote 61 On the basis of the musical texts alone it is impossible to determine the main direction of influence. This allows us to revisit the questions posed at the beginning of this article: In 1878, did Brahms and Schumann work out the cadenzas for K466 in some kind of concerted effort? If so, to what extent was their creative input informed by their earlier performance history of these cadenzas that had been stored in the minds and bodies of the musicians rather than on paper? Was Schumann still indebted to ideas that reached back as far as 1856 when Brahms had given his first concert performance of K466 with his own cadenza? Or had that performance sunk without a trace? How much of it could Brahms still have remembered, as he had not played cadenzas for K466 since the singular performance in the Mozart centenary concert of 1856?

Circumstances suggest that Schumann played the leading role during the exchange with Brahms. She had the incentive to prepare cadenzas for a concert in Hamburg in 1878, after two decade-long breaks (1859–68 and 1868–78). Nonetheless, through her relatively frequent renditions of K466 between 1857 and 1859, the cadenzas had become ‘embodied’ – as she suggested in the aforementioned diary entry of 29 September 1891 (‘in Fleisch und Blut übergegangen’). How much of that body memory had remained intact until 1878 remains unclear, nor do we know whether Schumann really intended to reconstruct her own performance practices of twenty years’ earlier. If Brahms responded primarily to whatever Schumann had remembered or newly created in 1878, did he act as a heavy-handed editor, keen to channel his spirit through Schumann's attempts, or as a sounding board for her ideas, giving collegial advice and suggesting alternative solutions? The latter is suggested by the fact that Brahms's and Schumann's versions of the first-movement cadenza of K466 differ in emphasis rather than substance. The two musicians made slightly different choices regarding the selection of material to be highlighted and the weighting of sections. Even if there were an element of competition between the two versions, discrepancies normally arise from conflicting aesthetic and motivic-thematic preferences. What is more, it is possible that Schumann and Brahms may have written down ideas that had first been mooted by their partners in the exchange.

This scenario productively highlights and challenges the correlation between autograph and authorship that reflects nineteenth-century philology. Schumann had ‘seen’ extensive portions of what she had regarded as ‘her’ cadenza in Brahms's handwriting. Upon consideration, Brahms's source may have triggered her memory of the collaborative moment during which the notated cadenza of 1878 had taken shape, allowing her to identify precisely the few passages in which the two scores pursued decisively different paths (Table 2): At point ‘A’, Schumann ventures further away from the tonic (JB2, bar 11). At point ‘B’, Brahms embarks on a harmonic detour, by interpolating a statement of the recitativo theme in a different key (JB2, bar 36). We can understand these borrowings to be situated within a discursive and collaborative process that is not captured directly in the musical notation. With Schumann's repeated performances of the cadenzas to K466 in the 1880s, the concerto was again assimilated into her body memory, and the intensive collaborative episode of 1878 receded. It required the encounter with Brahms's autograph in 1891, to allow Schumann to ‘relive’, as it were, and revisit her earlier experiences.

Table 2 Tonal and thematic design of Brahms's and Schumann's cadenzas to K466, mvt. i

Table 3 Performances of K466 in orchestral concertos at the Gewandhaus, Leipzig, 1800–1900. Source: www.gewandhausorchester.de/archiv/

Distributed Creativity

As we have seen, Clara Schumann's creation and performative appropriation of the cadenzas for Mozart's K466 was a fundamentally multi-modal process, shaped by her own listening, performing and reading and writing activities. Yet, this perspective is still too myopic. In viewing Schumann's cadenza for K466 exclusively in relation to Brahms, one fails to recognize that the creation of cadenzas had a multi-focal dimension as well. If Schumann had taken inspiration from the collaborative exchange with Brahms, why should she not have been receptive to the creative efforts of other musicians, and why would subsequent pianists not have been receptive to her ideas? After all, there were several precedents that she could have consulted in print, starting with August Eberhard Müller (1817) and Mozart's own student Johann Nepomuk Hummel (c. 1828).Footnote 62 Hummel's cadenza, published together with his chamber arrangements of selected Mozart concertos, earned him a commendation in Carl Czerny's influential Piano-Forte Schule.Footnote 63

It is worth recalling that the vast majority of notated cadenzas to Mozart's piano concertos (including his own) were not considered ‘musical works’ in their own right but didactic tools: They supported amateur performers, who did not (yet) possess the creative skills to write or improvise their own cadenzas. Additionally, they presented models to fledgling composer-performers in search of their own voice. Even Beethoven's cadenzas to K466 (WoO 58), which have long assumed canonical status in the performance history of this concerto, were conceived around 1808 for the benefit of his students Archduke Rudolph and, possibly, Ferdinand Ries.Footnote 64 Beethoven's cadenzas could also have formed a point of departure for Schumann: they were first printed as an appendix to a Viennese journal in 1836,Footnote 65 roughly a year before a 17-year old Clara Wieck toured to Vienna. The triumphant success she celebrated there was a crucial experience at a time when she had emancipated herself from her father.Footnote 66 Wider dissemination of Beethoven's cadenzas started with their edition in the Complete Work series in 1864,Footnote 67 published in the hiatus between Schumann's first run of performances in the 1850s and the London recital of 1868.

In the absence of musical sources before 1878, it escapes our knowledge when exactly Schumann discovered Beethoven's cadenzas. As the notated version of 1878 demonstrates, she was already under their spell by that time. Her cadenza for the first movement is evidently modelled on Beethoven's example,Footnote 68 highlighting the same themes from Mozart's concerto: the second subsidiary subject and the solo lead-in. With regard to the former, Schumann followed her famous forerunner (bar 17) (in contrast to Brahms) in placing Mozart's theme in B. Schumann, however, went directly for the minor key, whereas Beethoven presented it both in B major (introduced by a dramatic semitone shift in the bass, bars 14–15) and in B minor (bars 26–28) (Ex. 4 in comparison with Ex. 1). Schumann and Brahms take inspiration from both statements and roll their characteristics into one: the theme is subjected to imitative treatment, which is more widely spaced (6 rather than 4 crotchets), but at the same time made more complex by placing it in the right hand only and at the melodic interval of the sixth (rather than at the octave). In the cadenzas by Schumann and Brahms, the left hand is therefore free to harmonize the theme with chordal tremolos. Beethoven reserves this effect for the second, non-imitative presentation of the theme (bars 26ff.), where the arpeggiated chords in triplets (rather than tremolos) help to create a continuous flow in the ensuing modulation.

Ex. 4 Beethoven's cadenza to K466, mvt. i, bars 17–30

Close affinities such as these betray a dependency on, or homage to, Beethoven's model. In other places, the model is evoked by its absence. Brahms forewent the signature feature of Beethoven's cadenza: the emphatic trills at the beginning (bars 1–4) and end (bars 60–66). Schumann's earlier version sought to outdo Beethoven with a quadruple trill (CS2, bar 77), but toned the passage down in the printed version (bar 88). It seems that Brahms and the older Schumann took an aesthetic stance against Beethoven's domineering ego that threatened to crush Mozart's concerto under its sheer weight. In doing so, they resonate with Richard Kramer's spirited critique of Beethoven's WoO 58 as an act of violation: ‘the tunes are Mozart's but the touch, the rhetoric is emphatically Beethoven's’.Footnote 69 The physicality of Beethoven's pianism was already noted by his contemporaries. Hearing Mozart's student Hummel perform in the home of Mozart's widow Constanze in the early 1800s, Czerny contrasts his style favourably with that of his own teacher: ‘While Beethoven's playing was remarkable for his enormous power, characteristic expression, and his unheard-of virtuosity and passage work, Hummel's performance was a model of cleanness, clarity, and of the most graceful elegance and tenderness.’Footnote 70 According to Hummel's early biographer, this style of playing was endorsed by none other than Mozart himself. Having heard Hummel as the soloist in his C major concerto (probably K503) in Dresden (10 March 1789), he gave him the following advice:Footnote 71

You will treat your instrument like Raphael has done for his art. You will enchant your listeners and transport them to higher planes. So keep going, my son, avoid the all too common tinklings and barrel organ playing that sounds like a blacksmith hammering on nails, all the overpowering thrashing and throwing about of the hands and fingers, that silly critics unfortunately call art. Because of this, one can justly say aloud: Lord, forgive them, they know not what they do! Remain true to your innermost feelings, my Hansl, because they will never lead you astray.

It is striking that Hummel's cadenza to K466 does not live up to this aesthetic maxim.Footnote 72 Undercutting the opposition of brutal physicality (Beethoven's ‘touch’, in Kramer's words) and gentle elegance, it comes much closer to Beethoven's self-assertive style. This included the excessive use of Beethovenian trills (Hummel cadenza, bars 38–45, 55–60) that had appropriated as trademark of his own pianism.Footnote 73 Like Beethoven (and later Brahms and Schumann), Hummel selects the second subsidiary subject for elaboration in the cadenza, which is led through different keys (but without imitative treatment, bars 3–10), and supported by arpeggiated chord figurations in triplets (bars 11–20). In fact, this is the only motivic material from Mozart's concerto that features in Hummel's cadenza.Footnote 74

This example suggests that pianist-composers were not only aware of published cadenzas by their colleagues, but very open to absorbing ideas and techniques from them into their own works. While Hummel had styled himself into a genuine Mozartean and antipode of Beethoven, he could not resist the temptation to rival Beethoven on his own territory. Especially the grandiose trills mimic Beethoven's heavy-handed touch. As the nineteenth century progressed, the pool of possibilities increased, and with it the potential for intertextual relationships. While the emphasis on the second subsidiary subject gradually hardened into a convention, individual composer-pianists were at liberty to allude to specific passages from another cadenza or not consider them at all. Schumann and Brahms, for instance, were apparently not convinced to respond to the tradition of excessive trills, prominently introduced by Beethoven.

The extended overlap between the cadenza autographs of Brahms and Schumann has to be seen in light of this broader exchange entre collègues, in which ‘originality’ plays but a subordinate role. After all, as a child prodigy, Clara Wieck had played and memorized numerous notated cadenzas. In this process, she would also have experienced the difference of ‘touch’ between the concerto itself and the cadenzas, produced by other pianists to showcase their specific skills and preferences. This creative process feeds off the assimilation of, and response to, other cadenzas that were known to Schumann. Such familiarity may additionally have been gained from experiencing performances of K466 as a listener. The concerts at the Gewandhaus in Leipzig alone offered plenty of opportunities to hear how fellow pianists engaged with the D minor concerto (Table 3): from her own mother Marianne Wieck (1822, which the 2½-year old child may at least have heard practising at home) to Heinrich Dorn (1831), her near-contemporary Ignaz Tedesco (1836), Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1836, 1841), Ferdinand Hiller (1845) and the young Carl Reinecke (1849), graduate of the conservatoire at Leipzig. Even if Schumann did not attend all of these concerts in person, the close-knit musical circles in Leipzig facilitated personal meetings with resident and touring musicians.Footnote 75 As her Marriage Diary records, Mendelssohn's performance in the Gewandhaus concert of 4 February 1841 left a particularly strong impression on Schumann: ‘Mendelssohn played the D minor concerto and concluded the final movement in particular with a beautiful and artful cadenza. The concerto with its simple manner appealed to me exceedingly.’Footnote 76 Although only snippets of Mendelssohn's cadenza have survived in written form,Footnote 77 it is imaginable, if not likely, that the experience of the performance, and potentially subsequent discussions of it with her husband and Mendelssohn, also informed her own cadenzas to this concerto.

In this wider network of cadenzas studied and experienced, even negative reactions would count as influences. Schumann was less than impressed with Ferdinand Hiller's performance of Mozart's D minor concerto.Footnote 78 Albeit otherwise exceedingly fond of Hiller, she found him lacking in ‘the respect that one can demand of a good artist’ (doch nicht mit dem Respekte …, als man es von einem guten Künstler verlangen kann). Confronted with his licences, the orchestra almost fell apart after both cadenzas. It seems as though Hiller, who led the orchestra from the piano, played himself into such a virtuosic frenzy that he forgot to cue the orchestra back in. It is significant that Hiller's flawed performance triggered the memory of Mendelssohn's far superior cadenza, which Schumann had heard almost five years earlier: ‘I could not help being reminded of Mendelssohn, and with how much affection and mastery he executes such works at all times.’Footnote 79 For all her admiration for Mendelssohn, however, Schumann also distanced herself from aspects of his pianism that suffocated Mozart's style with Beethovenian bravura style (especially the double trill that concluded Mendelssohn's cadenza to the first movement).Footnote 80

As time progressed, Schumann was confronted with the sensationalist manners of her younger and flashier colleagues. While she aimed to remain at respectful terms with Anton Rubinstein, Carl Tausig, Hans von Bülow or Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, she registered their extrovert showmanship with unease, especially when she returned to the stage after a maternity break.Footnote 81 With regard to Mozart's concertos, Schumann had to fear little competition, since the majority of these virtuosos turned a blind eye to this repertoire, which would not have afforded sufficient opportunity to demonstrate their technical brilliance.Footnote 82 The only exception was Anton Rubinstein. In the 1850s, he had made a big splash with his unashamedly triumphant performances of K466. His cadenzas in particular were geared to provoke strong reactions. James W. Davidson, the music critic of The Times, was scandalized by Rubinstein's beastly performance of Mozart's D-minor concerto his 1858 recital in London:

A “lion” in the most leonine sense of the term, he treated the concerto of Mozart just as the monarch of the forest, hungry and truculent, is in the habit of treating the unlucky beast that falls to his prey. He seized it, shook it, worried it, tore it in pieces, and then devoured it, limb by limb.Footnote 83

Rubinstein's egocentric habitus could not have been any more different from Clara Schumann's concern for Texttreue and correct style. Her obituarist Bernhard Scholz noted, once more with a characteristic blending of the mind and the body:

She devoted herself completely and totally to the work of art. She sacrificed her personality to the endeavour to present it in its purity and individual character. But her own lifeblood throbbed in the flow of the notes, which she elicited from the instrument, and thus each of her efforts were replete with a living warmth and with the magic that emanated from her.Footnote 84

The contrast between Schumann's and Rubinstein's attitudes resulted in cadenzas to K466 that operate on different planes entirely.Footnote 85 At 131 bars, Rubinstein's cadenza is nearly twice as long. Schumann instead prioritized succinct and dense construction over indulgent virtuosic vagaries that elaborated routine passagework, often without thematic links to Mozart's concerto (e.g. Rubinstein, bars 68–83). The two pianists differed significantly also in the motivic material from Mozart they selected for their cadenzas (see Table 4 in comparison with Table 2). Whereas Schumann placed great emphasis on lyrical themes from the Solo Exposition (the soloist's Lead-in and Subsidiary Subject), Rubinstein extracted short snippets from the opening ritornello. Motivic fragments such as the circulating motive (Mozart, bars 21–23) and evaded cadence motive (Mozart, bars 71–73) are elaborated, expanded and, above all, layered with other material to create technically demanding textures. Thematically, both cadenzas concur significantly only in the use of the Closing Group motive. Yet even this similarity is undermined by a different structural function. Schumann employed it as a structural framing device. Having surprisingly suppressed it at the opening of the cadenza, Rubinstein presents it as the climactic point of internal sections (bars 31–43 and, in expanded form, 84–103) (Ex. 5).Footnote 86

Ex. 5 Anton Rubinstein, cadenza to Mozart, K466, mvt. i, bars 84–105

Table 4 Tonal and thematic design of Rubinstein's cadenza to K466, mvt. i

While the two cadenzas seem to operate on completely different aesthetic and pianistic planes, there are two arresting Brahmsian moments at the end of Rubinstein's cadenza. The treatment of the evaded cadence motif in parallel sixths (bars 107–114) in particular recalls the characteristic ‘touch’ and sound of Brahms's piano writing. Brahmsian rhythmic flexibility may further be recognized in the progressive rhythmic broadening of the Solo Lead-In – notably the only other motivic material shared between two cadenzas (bars 121 in quavers, 125 in crotched triples, 129 in crotchets).

The apparent cross-reference to Brahms begs tantalizing questions: Had Rubinstein intended to pay homage to Brahms, and, if so, why? After all, he was not present at Brahms's singular concert performance of K466. Or had he recalled Clara Schumann's interpretation of the cadenzas for K466, in which Schumann herself detected a distinctive Brahmsian flavour? However tempting this scenario might appear at first sight, it is ruled out by historical evidence: Rubinstein published his cadenza already in 1862, when Schumann had performed K466 a mere seven times, and in Rubinstein's absence. While Rubinstein's motives may be ultimately elusive, this stylistic cross-reference bears witness to the phenomenon that a cadenza that was geared to showcasing own pianistic genius, may temporarily pay tribute to the pianism of his colleagues, such as Brahms and Schumann. If he had no reservations about assimilating their personal styles, as he experienced them as listener or reader, Schumann may in turn have been receptive to influences from her colleagues.

Crucially, this tantalizing point of intersection would have gone unnoticed were it not for the testimony of the published scores of cadenzas by Rubinstein, Schumann and others. While further research is needed to locate Schumann's cadenzas to K466 in the wider context of all the cadenzas she had played, heard and studied, our reliance on the written record will only ever allow us to see the tip of the iceberg. All the different lines of investigation pursued in this article have demonstrated that the nineteenth-century performance culture of cadenzas is infinitely richer than surviving sources suggest. After all, ‘originality’, that shibboleth of romantic aesthetics, proves marginal to a genre that sprung from creative processes both embodied and distributed. The written scores are at best an imperfect and at worst a deceptive reflection of a lived reality that was stored also within body memory and that fed off substantial input both from the host concerto and from other performers’ responses to it. The philological and historical bias towards the written trace will only ever go some way to reconstruct the far richer and more complex circumstances to which Schumann's cadenzas, both performed and notated, owed their existence. In fact, Schumann herself fell victim to the misleading testimony of the notated scores, when she tried to isolate Brahms's original thread in a densely woven fabric of matted fibres. The problem of ‘authorship’ may ultimately defy a definitive answer. But it encourages music historians to think about the dimensions that lie beyond the score.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479409823000046