Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

1 Matt 28.1–10; Mark 16.1–8; Luke 24.1–12; John 20.1, 11–18; Mark 16.9; Gos. Pet. 12.50–56.

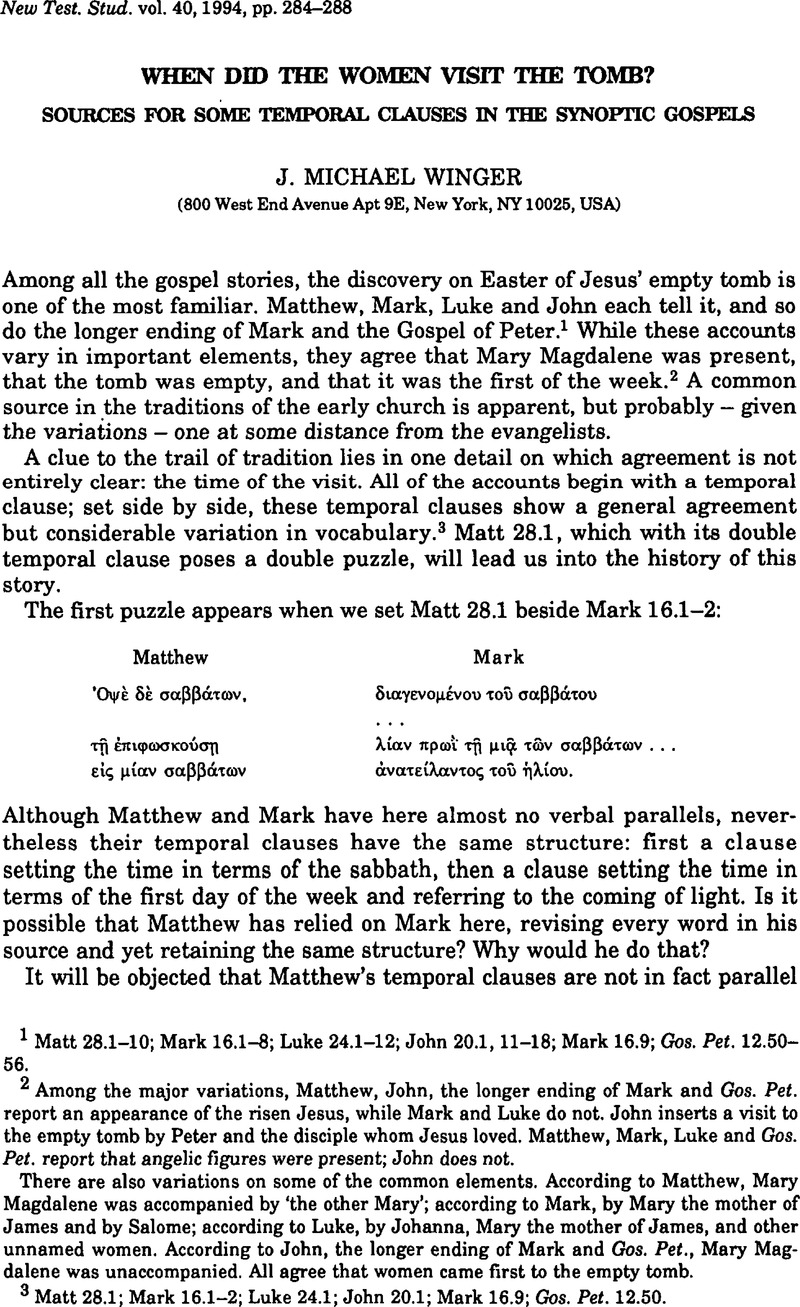

2 Among the major variations, Matthew, John, the longer ending of Mark and Gos. Pet. report an appearance of the risen Jesus, while Mark and Luke do not. John inserts a visit to the empty tomb by Peter and the disciple whom Jesus loved. Matthew, Mark, Luke and Gos. Pet. report that angelic figures were present; John does not.

There are also variations on some of the common elements. According to Matthew, Mary Magdalene was accompanied by ‘the other Mary’; according to Mark, by Mary the mother of James and by Salome; according to Luke, by Johanna, Mary the mother of James, and other unnamed women. According to John, the longer ending of Mark and Gos. Pet., Mary Magdalene was unaccompanied. All agree that women came first to the empty tomb.

3 Matt 28.1; Mark 16.1–2; Luke 24.1; John 20.1; Mark 16.9; Gos. Pet. 12.50.

4 Precisely what time might be indicated by ‘as it was becoming light’ is one of the minor uncertainties of this verse. The RSV, for example (‘toward the dawn’), preserves the ambiguity of the Greek as to whether twilight or the time just before twilight is referred to; note also that LSJ, s.v. G.II, gives the temporal meaning of ἐπι- in composition as ‘after’, so that the time in question here could be as late as ‘after dawn’.

If, on the other hand, the reference is – as I shall suggest – to sunset rather than dawn, the time referred to may range from before sunset to after dark.

5 Driver, G. R., ‘Two Problems in the New Testament’, JTS N.S. 16 (1965) 327–31.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

6 BAG, s.v. 3. This meaning, which harmonizes Matthew with the other gospels, is the sense of modern English versions (RSV, NRSV, NEB, REB, JB, NJB, NAB, TEV). The older, more literal AV and RV use the primary meaning of ὀψέ, even as they say that the time was ‘as it began to dawn’.

7 Moore, G. F., ‘Conjectanea Talmudica’, JAOS 26 (1905) 323–9Google Scholar. Moore advances no explanation for this curious idiom. E. Lohse (‘σάββατον κ.τ.λ.’, TDNT 7.1–35, 20 n. 159) writes of Luke 23.54, ‘The ref. is obviously to the shining of the first star as the Sabbath comes’; compare Moore's description of a similar theory that the reference is to the lighting of sabbath lamps as ‘entirely fanciful’ (‘Conjectanea’, 329).

8 Moore, ‘Conjectanea’, 328.

9 Ibid., 324.

10 Grintz, J. M., ‘Hebrew as the Spoken and Written Language in the Last Days of the Second Temple’, JBL 79 (1960) 32–47, 37–9Google Scholar. Grintz apparently reached his conclusions independently of Moore, to whose article he does not refer.

11 Black, M., An Aramaic Approach to the Gospels and Acts (3rd ed.; Oxford: Clarendon, 1967) 136–8Google Scholar. Black does not discuss the question of a Semitic original for ὀψὲ σαββάτων.

12 E.g., Mark 11.19 (so RSV, AV, RV); Gen 24.11 (LXX).

13 On the use of ![]()

![]() for evening, see Dalman, G. H., Aramäisch-Neuhebräische Handwörterbuch zu Targum, Talmud und Midrasch (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck u. Ruprecht, 1938) 228.Google Scholar

for evening, see Dalman, G. H., Aramäisch-Neuhebräische Handwörterbuch zu Targum, Talmud und Midrasch (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck u. Ruprecht, 1938) 228.Google Scholar

14 So Jastrow, M., Dictionary of the Targumim, Talmud Babli, Yerushalmi and Midrashic Literature (New York: Judaica, 1971)Google Scholar s.v.; Levy, J., Wörterbuch über die Talmudim und Midrashim (Berlin: Harz, 1924)Google Scholar s.v. This nuance is not always clear, however; see, e.g., b. Ber. 4a (quoted by Moore, ‘Conjectanea’, 326–7), where the time referred to seems to be the middle of the night. (For a countervailing suggestion that the Semitic original was Hebrew rather than Aramaic, see n. 15 below.)

15 In Hebrew ![]()

![]()

![]() we would have ‘the light towards the first of the week’, with Hebrew

we would have ‘the light towards the first of the week’, with Hebrew ![]() corresponding to Greek εἰς, which is not found with Luke's and G. Pet.'s uses of ἐπιφώσκω. This peculiarity might be taken to indicate that the Semitic original underlying Matthew's Greek text was Hebrew rather than Aramaic, which lacks the

corresponding to Greek εἰς, which is not found with Luke's and G. Pet.'s uses of ἐπιφώσκω. This peculiarity might be taken to indicate that the Semitic original underlying Matthew's Greek text was Hebrew rather than Aramaic, which lacks the ![]() . But the argument is inconclusive; εἰς could have been employed by the translator without a direct counterpart.

. But the argument is inconclusive; εἰς could have been employed by the translator without a direct counterpart.

16 There have been a variety of other attempts to explain Matthew's use of ἐπιφώσκω see esp. Turner, C. H., ‘Note on ἐπιφώσκειν’, JTS 14 (1913) 188–90Google Scholar; Burkitt, F. C., ‘ΕΠΙΦΩΣΚΕΙΝ’, JTS 14 (1913) 538–46CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Gardner-Smith, P., ‘ΕΠΙΦΩΣΚΕΙΝ’, JTS 27 (1926) 179–81CrossRefGoogle Scholar. For the reasons stated in the text, below, I prefer Moore's thesis.

17 The argument is actually rather complicated; it would seem that Luke has drawn on a tradition common to Matthew, but, because this tradition conflicts with another tradition about the time of the visit to the tomb, Luke has displaced ἐπιφώσκω to a time (Friday evening), where, in Luke's judgment, it fits. This other tradition is represented in the words őρθρου βαθέως (Luke 24.1), which have parallels in both Mark 16.2 (λίαν πρωΐ) and John 20.1 (πρωΐ σκοτίας ![]() τι οὕσης); cf. also Gos. Pet. 12.50 (ὄρθρου) and Mark 16.9 (πρωΐ). Various relationships are possible. Luke's phrase could be his redaction of Mark's, but it could also have an independent source; see further n. 20 below. On the meaning of őρθρου βαθέως in Luke 24.1, see now Wallace, R. W., ‘ΟΡΦΡΟΣ’, TAPA 119 (1989) 201–7, 204–5,Google Scholar suggesting ‘that ὄρθρος βαθύς is that part of ὄρθρος which precedes any light’.

τι οὕσης); cf. also Gos. Pet. 12.50 (ὄρθρου) and Mark 16.9 (πρωΐ). Various relationships are possible. Luke's phrase could be his redaction of Mark's, but it could also have an independent source; see further n. 20 below. On the meaning of őρθρου βαθέως in Luke 24.1, see now Wallace, R. W., ‘ΟΡΦΡΟΣ’, TAPA 119 (1989) 201–7, 204–5,Google Scholar suggesting ‘that ὄρθρος βαθύς is that part of ὄρθρος which precedes any light’.

Of Gos. Pet.'s three uses of ἐπιφώσκω, 2.5 parallels Luke 23.54 (referring to the approaching sunset on Friday), 9.35 parallels Matt 28.1 (referring to the night between Saturday and Sunday), and 9.34 is without canonical parallel. But this third use may nevertheless reflect dependence on Matthew and Luke; the term's appearance in different but related contexts in these two gospels gives it an importance which might invite the author of Gos. Pet. to use it in yet another context related to both of the other two.

18 Διαγίνομαι is not the most obvious translation for ![]() or

or ![]() one might rather expect ἐκπορεύομαι, or some other ἐκ – compound – but it is certainly possible. Although διαγίνομαι never translates

one might rather expect ἐκπορεύομαι, or some other ἐκ – compound – but it is certainly possible. Although διαγίνομαι never translates ![]() in the LXX, two other δια- compounds do: διαπορεύομαι, Josh 15.3, and διέρχομαι, Josh 16.6 and some seven other occurences (six in Joshua).

in the LXX, two other δια- compounds do: διαπορεύομαι, Josh 15.3, and διέρχομαι, Josh 16.6 and some seven other occurences (six in Joshua).

19 Moore suggested this, but did not pursue the suggestion (‘Conjectanea’, 328).

20 Mark also inserts the phrase λίαν πρωΐ, ‘very early’. This could be his own amplification of his source, or he might have taken it from another source. If it comes from another source, that source could also underlie the parallel phrases noted above (n. 17).

21 Neirynck, F., ‘Les femmes au tombeau: étude de la rédaction Matthéenne (Matt. XXVIII.1–10)’, NTS 15 (1968–1969) 168–90CrossRefGoogle Scholar. Neirynck shows how all such differences may be understood as redactional; but once it is shown that Matthew had another source, even if its contents are unknown, then the mere possibility of redaction is not sufficient to exclude use of the other source.

22 So Moore, ‘Conjectanea’, 328, and Grintz, ‘Hebrew’, 38; Black, Aramaic Approach, 138, says ‘late Saturday afternoon or evening’, but this is only on the basis of the second phrase – the first rules out the afternoon.

23 So Crossan, J. D., The Cross That Spoke (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1988) 279Google Scholar, and, with reservations, Allen, W. C., A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel according to St Matthew (ICC; Edinburgh: Clark, 1912) 300–1.Google Scholar

24 This article is adapted from a section of a longer paper originally written for Raymond E. Brown, for whose guidance I am grateful.