Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

[1] The strongest case for anacolouthon is made by Cranfield, C. E. B., A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1975) 269–74.Google Scholar He also lists, as scholars who believe ὥσπερ is correlative to οὕτως, Barrett, C. K., A Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans (London: A & C Black, 1957) 109–10Google Scholar; Cerfaux, L., Le Christ dans la théologie de Saint Paul (Paris: Cerf, 1951) 178Google Scholar; and of Scroggs, R., The Last Adam: A Study in Pauline Anthropology (Oxford: Blackwell, 1966) 79 n. 13.Google Scholar

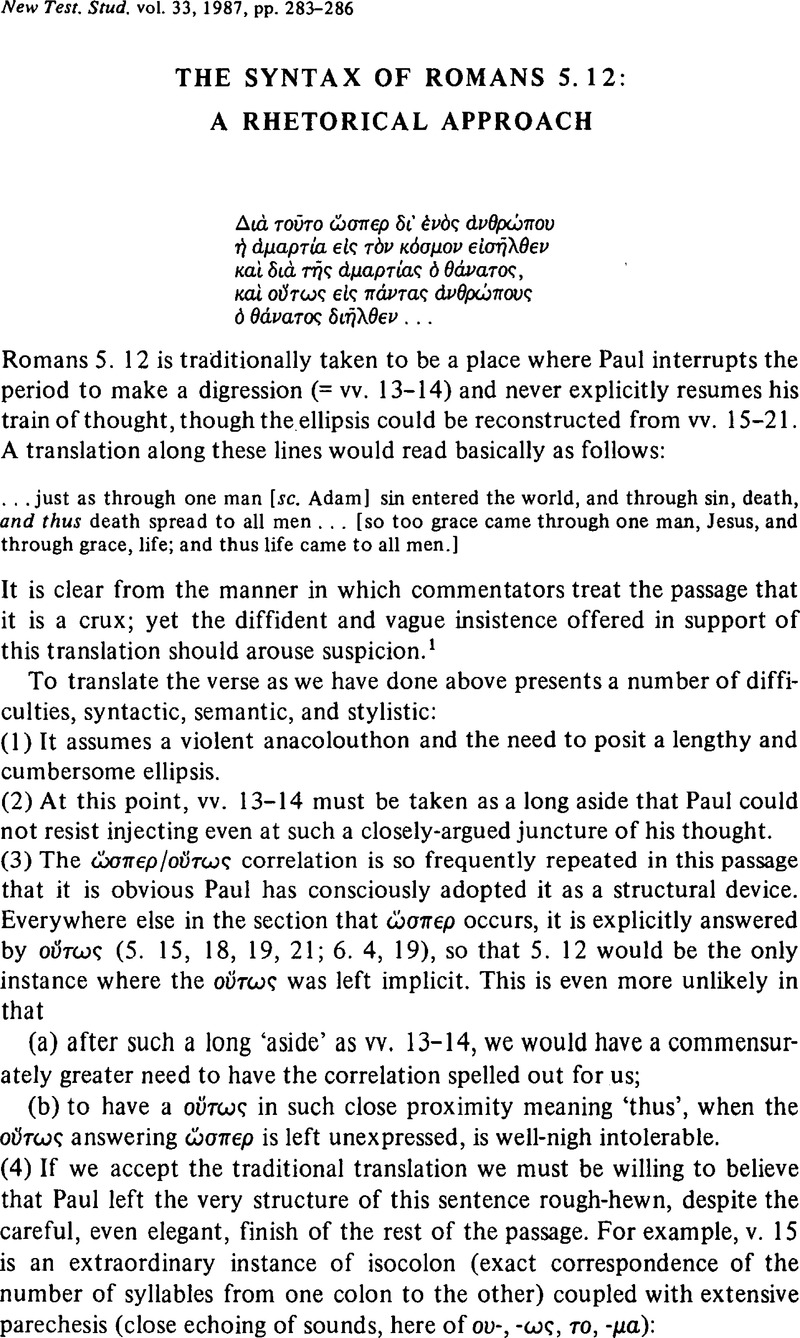

[2] This is exactly what is suggested by Cranfield, , Commentary 272 n. 5Google Scholar (iii): ‘the emphatic position of δι ένός άνθρώπου in v. 12a suggests that in the corresponding apodosis the emphasis would be on something answering it’, except that he imagines another δι ὲνὸς άνθρώπου in the ellipsis (referring not to Adam but to Christ). He assumes, Commentary 272 n. 5 (iv), that if one reads οὓτως as correlative to one ὥσπερ one must understand πάντες at the end of v. 12 as the analogue to δι ὲνὸς ἀνθρώπου.

[3] For the figure κλῷμαξ cf. e.g. Quintilian Institutio oratoria 9.3. 54–57. Its Latin name there is gradatio. It was also known as sorites, for which (including Paul's explicit use of it elsewhere in Rom) cf. Henry Fischel, A. in Hebrew Union College Annual 44 (1973) 119–51.Google Scholar He discusses the figure under seven headings;I would classify Rom 5. 12 under his Type IV.

[4] Rhetoric 1355a 6;18, 1356a 35–1357b 25, 1393a 23–1403a 33, et passim. For a useful introduction to the enthymeme, with more bibliography, cf. Kennedy, G. A., The Art of Persuasion in Greece (Princeton NJ: Princeton University, 1963) 95–103.Google Scholar

[5] Rhetoric 1358a 14, 1397b 12–27.

[6] For a similar emphasis in a not dissimilar construction, cf. 1 Tim 2. 5.

[7] Denniston, J. D., The Greek Particles (Oxford: Clarendon, 2 1954) 325–6.Google Scholar

[8] Smyth, H. Weir, Greek Grammar (Cambridge MA: Harvard University, 1956) § 2882b.Google ScholarCranfield, , Commentary 272Google Scholar n. 5 (i) lists several Pauline instances of καὶ οὕτως and maintains that this phrase must mean ‘and so’ (Rom 11. 26; 1 Cor 7. 36, 11. 28; Gal 6. 2). By listing these examples he in fact demonstrates my point:

(1) in Rom 11. 26 the οὕτως is correlative to the καθώς, even if the καὶ is copulative;

(2) in the other cases there is nothing to which the οὕτως could possibly be correlative, and the καί is clearly copulative. The similarity of these loci to our passage is sheerly accidental.

[9] Cf. e.g. Parry, R. St. J., The Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Romans (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1912) 85Google Scholar: ‘καὶ is the simple conj[unction] and the clause is part of the ὥσπερ sentence, not the apodosis: that would require ο;ὕτως καί’, and Cranfield, Commentary ad loc.