Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

page 609 note 1 Thanks are due to Drs. Ehrman, Bart D., Elliott, J. K., Fee, Gordon D.Hoehner, Harold W.Metzger, Bruce M., and Silva, Moises who looked at a preliminary draft of this paper and made several valuable suggestions.Google Scholar

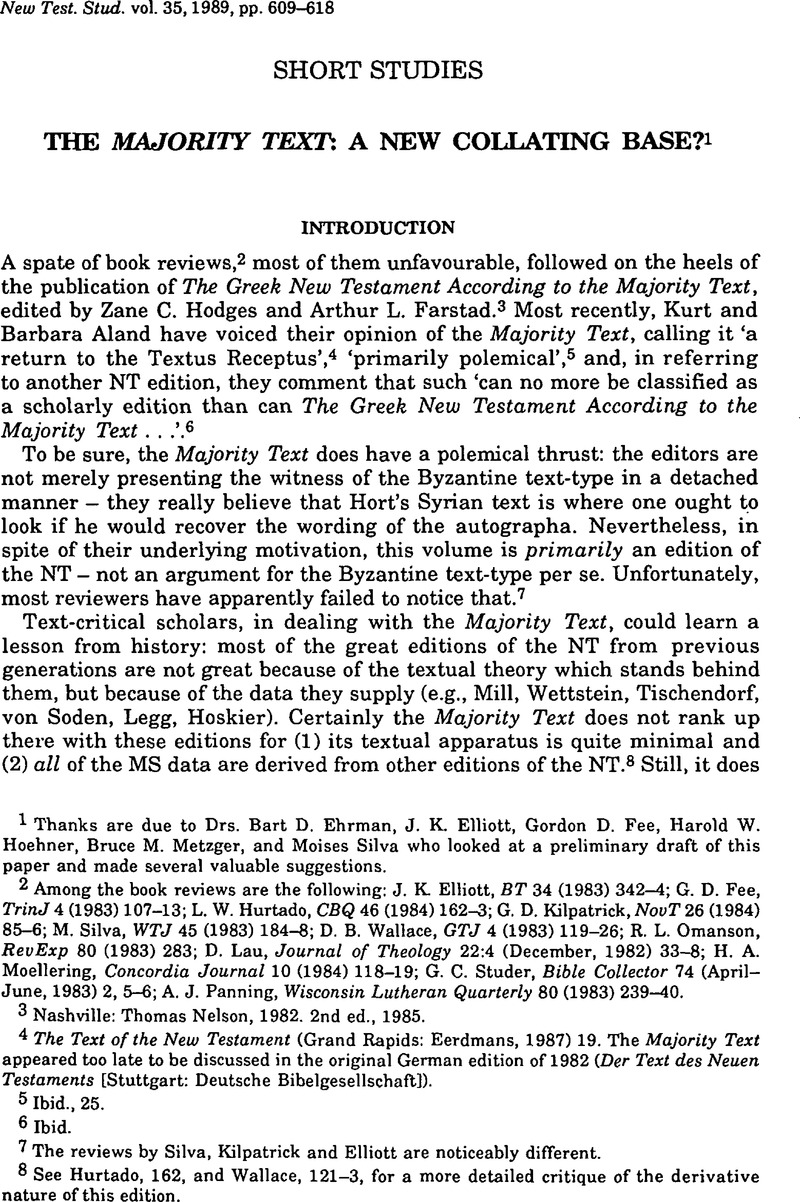

page 609 note 2 Among the book reviews are the following: Elliott, J. K., BT 34 (1983) 342–4;Google ScholarFee, G. D., TrinJ 4 (1983) 107–13;Google ScholarHurtado, L. W., CBQ 46 (1984) 162–3;Google ScholarKilpatrick, G. D., NovT 26 (1984) 85–6;Google ScholarSilva, M., WTJ 45 (1983) 184–8;Google ScholarWallace, D. B., GTJ 4 (1983) 119–26;Google ScholarOmanson, R. L., RevExp 80 (1983) 283;Google ScholarLau, D., Journal of Theology 22:4 (12, 1982) 33–8;Google ScholarMoellering, H. A., Concordia Journal 10 (1984) 118–19;Google ScholarStuder, G. C., Bible Collector 74 (10–06, 1983) 2, 5–6;Google ScholarPanning, A. J., Wisconsin Lutheran Quarterly 80 (1983) 239–40.Google Scholar

page 609 note 3 Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1982. 2nd ed., 1985.Google Scholar

page 609 note 4 The Text of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987) 19.Google Scholar The Majority Text appeared too late to be discussed in the original German edition of 1982 (Der Text des Neuen Testaments [Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft]).Google Scholar

page 609 note 5 Ibid., 25.

page 609 note 6 Ibid.

page 609 note 7 The reviews by Silva, Kilpatrick and Elliott are no 3 ticeably different.Google Scholar

page 609 note 8 See Hurtado, , 162, and Wallace, 121–3, for a more detailed critique of the derivative nature of this edition.Google Scholar

page 610 note 1 As contrasted with von Soden's impossible apparatus!Google Scholar

page 610 note 2 Fee's, G. D. review was the one exception. In his opening paragraph, he writes (107): As the title implies, this is an edition of the Greek New Testament as it can be retrieved from the majority of Greek NT manuscripts (MSS), also commonly known as the Byzantine texttype. In itself this could serve as a useful tool, by providing a more definitive collating base (for some purposes) and a better textual reference point than is available in the time honored Textus Receptus (TR). Yet Fee immediately moves into a critique of the textual theory which stands behind the Majority Text. He does not again address the potential value of the Majority Text as a collating base (except indirectly in his final paragraph: ‘All in all, then, this work, which has so much to commend it as a presentation of the Majority Text, altogether fails in its real reason for existence, viz., as a critical edition of the original text’ [112]).Google Scholar

page 610 note 3 The NT portion (vol 5) had the TR as the Greek text along with several versions; the apparatus listed variant readings from codex Alexandrinus. Vol 6 contained variant readings from another 15 authoritiesGoogle Scholar(see Metzger, B. M., The Text of the New Testament, 2nd ed. [Oxford: Oxford University, 1968] 107).Google Scholar

page 610 note 4 For a good summary on the history of the editions of the NT, consult Metzger, Text 95–146 and Aland-Aland, Text 3–47. The material in this paper is selected merely for illustrative purposes.Google Scholar

page 610 note 5 Bengel's text marked a milestone in text-critical studies for at least two, if not three, reasons: (1) he recognized at least two text-types (‘nations’) (the Asiatic [= Byzantine[ and the African [= Alexandrian-Western]); (2) he ‘formulated a canon of criticism that, in one form or other, has been approved by all textual critics since…: proclivi scriptioni praestat ardua (“the difficult is to be preferred to the easy reading”)’ (Metzger, Text 112); (3) his text was something of a forerunner to the UBSGNT in that he rated, via a system of (Greek) letters, the authenticity of the various readings (cf. the Alands' comment on the use of this system in UBSGNT [Text 44]). In addition, he duplicated the variant readings of Mill's text with collations from another dozen MSS.Google Scholar

page 610 note 6 His edition ‘provides a thesaurus of quotations from Greek, Latin, and rabbinical authors, illustrating the usage of words and phrases of the New Testament’ (Metzger, Text 114). Besides this, he substantially increased the list of variae lectiones (with their witnesses) found in previous textual apparatuses.Google Scholar

page 611 note 1 In this, we perhaps have a modern parallel: cf. the many modern English editions of the NT which leave Mark 16. 9–20 and the pericope adulterae in the text (though almost always with some sort of marginal note).Google Scholar

page 611 note 2 Hoskier, H. C., Concerning the Text of the Apocalypse, 2 vols. (London: Bernard Quaritch, 1929).Google Scholar

page 611 note 3 The New Testament in Greek: The Gospel according to St. Luke. Part One, Chapters 1–12 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1984), and Part Two, Chapters 13–24 (1987). Abbreviated IGNT throughout the rest of this paper.Google Scholar

page 611 note 4 Greenlee, J. H., Introduction to New Testament Textual Criticism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964) 135–6.Google Scholar

page 611 note 5 Streeter, B. H., The Four Gospels: A Study of Origins (London: Macmillan, 1924) 105 (cf. also 81–82, 95).Google Scholar

page 611 note 6 Ibid., 83.

page 612 note 1 Metzger, B. M., Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Greek Palaeography (Oxford: University, 1981) 52 (n. 151).Google Scholar

page 612 note 2 Globe, A., ‘Serapion of Thmuis as Witness to the Gospel Text Used by Origen in Caesarea’, NovT 26 (1984) 114.Google Scholar

page 612 note 3 Ibid., 100–4.

page 612 note 4 By accessible we mean that such is an immediately known quantity because it is found in a commonly printed edition.Google Scholar

page 612 note 5 Aland, K., however (as representative of many German textual critics), does not like this approach, but would rather reconstruct his own text as the baseline and show variants from it in the apparatus. Cf. his reviews of Luke 1–12 (IGNT) in Gnomon 56 (1984) 481–97 and TheolRev 80 (1984) 441–8. As well, see his own plan for a major edition of the Greek NT, ‘Novi Testamenti Graeci Editio Maior Critica’, NTS 16 (1970) 163–77. His terse comment in Text sums up his views on this issue; ‘In any case, the goal of preparing a critical edition has been abandoned — by Legg, by the International Project, and by Dearing. It is being pursued now only by the Novi Testamenti editio critica maior…’ (24). (Cf. also J. O'Callaghan's review of IGNT in Bib 65 [1984] 591–3.) There is obvious value in Aland's approach (the pocket editions of UBSGNT and Nestle-Aland26 would lose most of their worth if they used the TR as their text). Nevertheless, the qualitative distinction (involving, among other things, cost and time) between a text which is designed for scholarly study (e.g., IGNT) and one intended (in light of present knowledge) to reproduce the autographs (e.g., UBSGNT) ought to be taken into consideration. Here, the example of WH is helpful: on one level, their edition of the NT made no advances over Tischendorf as its apparatus was virtually non-existent. Yet, Hort's textual theory, combined with the readings of ‘The New Testament in the Original Greek’, marked a new advance in NT textual criticism. Just as Hort based his textual decisions on the testimony found in Tischendorf, so too manual editions in the future will no doubt be based on the apparatus criticus of IGNT as well as that of the Editio Maior.Google Scholar

page 613 note 1 Accessibility is perhaps one reason why Legg used the Westcott-Hort text as his baseline in his volumes on Matthew and Mark and departed from the TR. That is, the WH text was equally accessible when he published in 1935 and 1940 (of course, it was also the preferred text). Conversely, lack of accessibility seems to be the reason why Streeter did not even take his own advice in determining the Byzantine text from Byzantine MSS (cf. The Four Gospels 147 with 83), but instead fell back on the TR.Google ScholarWisse, F. (The Profile Method for the Classification and Evaluation of Manuscript Evidence [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982] 26) argues against accessibility as a real reason for the use of the TR: The reason for using the TR as a collation base is not entirely due to custom and availability. Asa matter of fact, the Nestle-Aland text is much more accessible. More likely the use of the TR is due to the general repudiation of the Byzantine text since Hort. The TR has become the ‘whipping boy’ in lieu of the Byzantine text. It is considered the ‘absolute zero’ in NT textual criticism. Departure from the TR [according to most textual critics] automatically bestows favor on a variant.Google Scholar

page 613 note 2 Based on the first edition of the Majority Text (though I have been assured by Farstad, A. L. that the second edition is simply a ‘corrected’ edition) and the 1825 Oxford edition of the TR.Google Scholar

page 613 note 3 Significantly, Zuntz, G. (‘The Byzantine Text in New Testament Criticism’, JTS 43 [1942] 26) has well anticipated this difference between the TR and the Byzantine text: The vacuum has up till now been filled by a problematical substitute: the Textus Receptus. It is evidence of the fixity of the Byzantine tradition that, as a rough and ready instrument, this substitute has enabled scholars to achieve important results. But it cannot ensure scientific exactness.… In consequence of this compromising pedigree the Textus Receptus exhibits, in a generally Byzantine setting, a certain, or rather an uncertain, number of individual, and also some ‘good, old’ readings. Nobody can tell at how many places it differs from the Byzantine norm; they mustbe hundreds. And that is our standard!Google Scholar

page 614 note 1 If, indeed, there was a single Byzantine archetype. But cf. Birdsall, J. N., ‘The New Testament Text’, in The Cambridge History of the Bible (edd. Ackroyd, P. R. and Evans, C. F. [Cambridge: University, 1970]) 1: 318–23;Google Scholar see also his suggestive studies, ‘The Text of the Gospels in Photius’, JTS 7 (1956) 42–55, 190–8,Google Scholar and ‘The Text ofthe Acts and the Epistles in Photius’, JTS 9 (1958) 278–91.Google Scholar

page 614 note 2 Wisse, who developed the Claremont Profile Method for identifying textual affinities among GreekMSS (especially among minuscule MSS), after some rather critical comments on von Soden's accuracy, has this to say (17–18): Harsh as one must be on the quality of von Soden's end product and general procedure, one cannot ignore his achievement. More than 1200 minuscules were examined by von Soden in whole or in part. His classification is in the great majority of cases the only information we have about the text of MSS. Years of usage have shown that von Soden's classifications of MSS, although not always correct, are usually helpful.… Von Soden has given the student of groups a starting point, not a finished product.… His legacy does not include a trustworthy method for discovering or studying groups. Rather, he gave a general picture of the mass of minuscules in terms of groups, and the promise that order can be brought into the chaotic world of Byzantine NT MSS.Google ScholarSee also Royse, J. R., ‘Von Soden's Accuracy’, JTS 30 (1979) 166–71.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 614 note 3 Silva, in his review, counted seventy Mpt readings in the Majority Text's apparatus for Matthew. This is less than one tenth of all the variants listed. Further, there are almosttwice as many variants between the Majority Text and the TR in Matthew (134). Thus even if Hodges and Farstad were wrong on every Mpt reading (i.e., as representing the Byzantine archetype), their text would still be twice as accurate as the TR on this score.Google Scholar

page 614 note 4 Of course, differences from the Byzantine text-type are, by themselves, an imperfect indicator of a particular MS's textual affinities. (Cf. Colwell, E. C., Studies in Methodology in Textual Criticism of the New Testament [Leiden: Brill, 1969] 5–6 and Greenlee, 139–41.)Google Scholar In reality, such differences only constitute the first step in determining consanguinity. This has been well recognized since Colwell, E. C. and Tune, E. W. broke new ground, methodologically speaking, with their essay, ‘The Quantitative Relationships Between MS Text-Types’, in Biblical and Patristic Studies in Memory of Robert Pierce Casey (edd. Birdsall, J. N. and Thomson, R. W. [Freiburg: Herder, 1963] 25–32;Google Scholar reprinted in Colwell, E. C., Studies in Methodology, under the title, ‘Method in Establishing Quantitative Relationships Between Text-Types of New Testament Manuscripts’ [56–62]).Google ScholarMost recently, Ehrman, B. D. has made some helpful methodological refinements (see his ‘Methodological Developments in the Analysis and Classification of New Testament Documentary Evidence’, NovT 29[1987] 22–45Google Scholar and ‘The Use of Group Profiles for the Classification of New Testament Documentary Evidence’, JBL 106 [1987] 465–86).Google Scholar In ‘Methodological Developments’, Ehrman ably points out the inadequacy of determining textual consanguinity by a mere tabulation of variation from the TR. Yet, in his approach, dubbed the ‘Comprehensive Profile Method’, which was ‘conceived as complementary to a quantitative analysis’ (44), Ehrman still prefers the TR to the Majority Text as a representative of the Byzantine text-type (though primarily for traditional reasons: ‘Unless we want to begin our textual studies with a tab[u]la r[a]sa, ignoring, in effect, the work of the previous 200 years, we should continue using the TR for our collations’ [correspondence of B. D. Ehrman to D. B. Wallace, August 3, 1987]).

page 615 note 1 Though Erasmus did not employ this MS to a great extent ‘because he was afraid of its supposedly erratic text’ (Metzger, Text 102), still he did use it. Furthermore, the TR is not really identical with Erasmus’ text (the 1825 Oxford edition which is the standard edition for collating was the end result of a long process which started with Erasmus; this TR also picks up some minor readings from the Complutensian Polyglot [a text allegedly based on ancient codices] as well as a few readings from codices Bezae and Claromontanus [ibid., 97–8, 104, 105]).

page 615 note 2 In Streeter's attempt to reconstruct the Caesarean text-type against a TR baseline, he complained about ‘the printed T.R., which has, besides some very late readings, a few derived from Codex 1. Since this MS. was used by Erasmus, the T.R. occasionally supports fam. θ against the Byzantine text’ (The Four Gospels 94 [n. 1]). In a cursory look at the Majority Text's apparatus in Matthew, I counted forty-eight TR-NA26 (= UBS3) agreements against the reading of the Byzantines. Further, the recent study by Globe on the Caesarean text (‘Serapion’) could have benefited much from a collation against the Byzantine text rather than the TR. This cuts both ways, however. Wisse (Profile Method 26) has pointed out that The TR is by no means the ‘absolute zero’ of the Byzantine text. It departs from the common denominator more frequently than the mass of Byzantine minuscules. The irony is that when the TR departs from the main Byzantine groups, usually some members of Lake's Caesarean group will support the Byzantine groups. Thus what appears to be a good ‘Caesarean’ reading is often an unquestionable part of the Byzantine text.Google Scholar

page 616 note 1 Profile Method, 38.Google Scholar

page 616 note 2 Westcott, B. F. and Hort, F. J. A., The New Testament in the Original Greek, vol. 2: Introduction [and] Appendix (London: Macmillan, 1882) 115–17: In themselves Syrian readings hardly ever offend at first. With rare exceptions they run smoothly and easily in form, and yield at once to even a careless reader a passable sense, free from surprises and seemingly transparent. But when distinctively Syrian readings are minutely compared one after the other with the rival variants, their claim to be regarded as the original readings is found gradually to diminish, and at last to disappear … there are, we believe, no instances where both [the transcriptional and intrinsic evidence] are clearly in favour of the Syrianreading, and innumerable where both are clearly adverse to it.… It follows that all distinctively Syrian readings may be set aside at once as certainly originating after the middle of the third century, and therefore, as far as transmission is concerned, corruptions of the apostolic text.Google Scholar

page 616 note 3 Even Kilpatrick, G. D., who has defended not a few Byzantine readings (cf. ‘The Greek New Testament Text of Today and the Textus Receptus’ in The New Testament in Historical and Contemporary Perspective, edd. Anderson, H. and Barclay, W. [Oxford: Blackwell, 1965] 189–208)—and is, predictably, oft-quoted by majority-text advocates — in his review of The Majority Text, argues on the basis of the history of transmission (which seems so unlike a thorough-going eclectic!) that the Byzantine text-type is decidedly inferior: ‘Hodges’ and Farstad's view must explain two features, first that there is no evidence for Hort's Syrian text before thefourth century, and second that the dominant text of the second and third centuries is so different’ (85–6).Google Scholar

The best case for the value of the Byzantine text-type has been made, in my opinion, by H. A. Sturz, The Byzantine Text-Type and New Testament Textual Criticism (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1984). Sturz differs from majority-text advocates in that he sees the Byzantine text-type as an independent text-type (along with the Alexandrian and Western), but not one which has exclusive rights on the wording of the autographa. But cf. especially the reviews by Holmes, M. W. (TrinJ 6 [1985] 225–8),Google ScholarFee, G. D. (JETS 28 [1985] 239–42),Google Scholar and Elliott, J. K. (NovT 28 [1986] 282–4).Google Scholar

page 617 note 1 It is interesting that Zuntz also advocated using the Byzantine text as a baseline — regardless of one's view of this particular text-type: ‘The appreciation of the threefold usefulness, to the critic, of the Byzantine norm, that is, as a basis for collation and for defining divergent forms of the text, and as a means for relieving the apparatus criticus, is independent of hisattitude towards, and of his interest in, later forms of the sacred text, and Byzantine studies ingeneral’ (27).Google Scholar

page 617 note 2 In the IGNTP's Luke 1–12 at least two allusions to the exorbitant costs can be detected in the introduction: ‘During the period of preparation the cost of conventional typography had risen to such an extent that the Clarendon Press proposed that publication should be by means of offset lithography from typewritten copy’ (v) and ‘for technical reasons S is used to denote the Codex Sinaiticus, the uncial manuscript commonly designated S being here cited under its alternative denomination of 028’ (viii). In this second quote, presumably the technical reasons are related to the typographical change. Suffice it to say that in terms of proofreading as well as book-length a Byzantine text baseline would have helped further to reduce the costs of production.Google Scholar

page 617 note 3 For the pericope adulterae half of the adopted readings are supported by a minority of MSS. In Revelation, by collating the Majority Text against the data in Hoskier, I was able to detect more than 150 minority readings adopted by the editors.Google Scholar

page 617 note 4 That is to say, whenever the editors have successfully reconstructed the archetypal reading, the Byzantine reading is thereby highlighted; and whenever they simply reproduce the later Ecclesiastical text, they have preserved the most inferior text (which, as we mentioned earlier, is the best text for a collating baseline).Google Scholar

page 617 note 5 Cf. the indictments against von Soden in Zuntz, 25; Aland-Aland, Text 23; and Streeter, The Four Gospels 147.Google Scholar

page 618 note 1 The CPM suffers primarily from the fact that the method has only been applied in a few chapters of the NT (e.g., Luke 1–24 by Wisse, and the Johannine epistles by Richards, W. L. [The Classification of the Greek Manuscripts of the Johannine Epistles (Missoula: Scholars, 1977)]). Consequently, although it is a vastly superior method to collations from secondary sources (and should have been consulted by the editors of the Majority Text—in fact, performed by them!), we must wait some time for the application of CPM on most of the NT text.Google Scholar

page 618 note 2 According to Ehrman (n. 4, p. 614), the adoption of the Majority Text as a collating base wouldseem to cancel out all previous studies which were collated against the TR. Metzger sees the problem as less severe: ‘Perhaps the only disadvantage is that then previously collated manuscripts prepared against the TR cannot (without some adjustment) be easily utilized along with newly collated manuscripts’ (correspondence of B. M. Metzger to D. B. Wallace, July 27, 1987).

In response, two points can be made: (1) Any collations using the Majority Text as the baseline should also include the TR in the collation. This will not only — to some degree at least — preserve the continuity with previous studies, but will also highlight the differences between the Majority Text and the TR. (2) If the challenge seems too great, one must never forget that New Testament textual criticism is a ‘game of inches’. Methodological precision in this field of study is a sine qua non. Zuntz, almost in anticipation of this problem, argues well for the use of the Byzantine text as a collating base (as opposed to the TR as well as to a critically reconstructed text) (28–30). And more recently, Fee, G. D., before the Majority Text was published, used a provisional majority text as his baseline in some specialized studies (cf. ‘Origen's Text of the New Testament and the Text of Egypt’, NTS 28 [1982] 348–64).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 618 note 3 The Four Gospels, 147.