Article contents

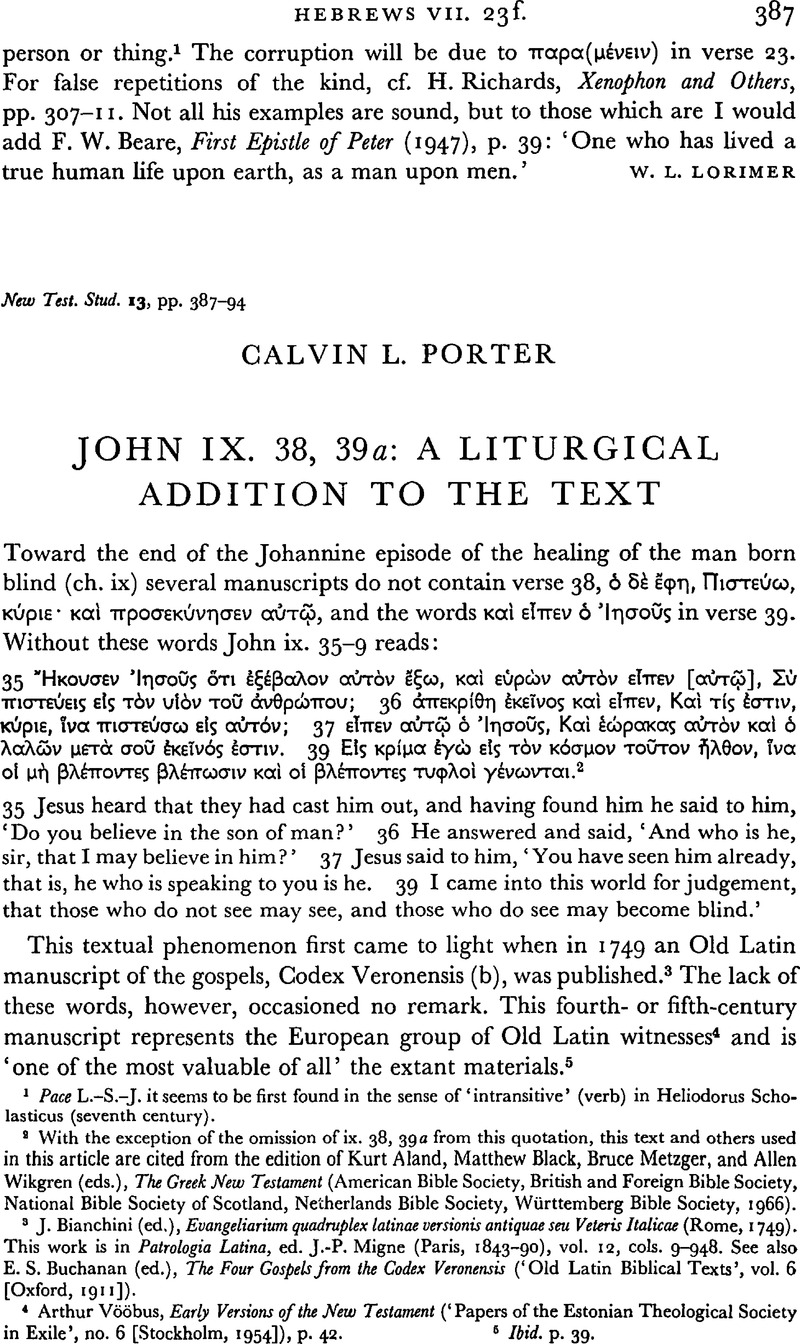

John ix. 38, 39a: A Liturgical Addition to the Text

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Short Studies

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1967

References

page 387 note 1 Pace L.-S.-J. it seems to be first found in the sense of ‘intransitive’ (verb) in Heliodorus Scholasticus (seventh century).

page 387 note 2 With the exception of the omission of ix. 38, 39a from this quotation, this text and others used in this article are cited from the edition of Kurt, Aland, Matthew, Black, Bruce, Metzger, and Allen, Wikgren (eds.), The Greek New Testament (American Bible Society, British and Foreign Bible Society, National Bible Society of Scotland, Netherlands Bible Society, Württemberg Bible Society, 1966).Google Scholar

page 387 note 3 Bianchini, J. (ed.), Evangeliarium quadruplex latinae versionis antiquae seu Veteris Italicae (Rome, 1749)Google Scholar. This work is in Patrologia Latina, ed. Migne, J.-P. (Paris, 1843–90), vol. 12, cols. 9–948Google Scholar. See also Buchanan, E. S. (ed.), The Four Gospels from the Codex Veronensis (‘Old Latin Biblical Texts’, vol. 6 [Oxford, 1911]).Google Scholar

page 387 note 4 Arthur Vööbus, Early Versions of the New Testament (‘Papers of the Estonian Theological Society in Exile’, no. 6 [Stockholm, 1954]), p. 42.Google Scholar

page 387 note 5 ibid. p. 39.

page 388 note 1 Constantine Tischendorf (ed.), Bibliorum Codex Sinaiticus Petropolitanus (Leipzig: Giesecke and Devrient, 1862), 4 vols.Google Scholar

page 388 note 2 Constantine Tischendorf (ed.), Novum Testamentum Graece (Editio octava critica maior; Giesecke and Devrient, 1869, 1872), 1, 857.Google Scholar

page 388 note 3 See Lagrange, M.-J., ‘L'origine médiate et immédiate du Ms. Sinaïtique’, Revue Biblique, xxxv (1926), 91 ff.Google Scholar

page 388 note 4 Eberhard, Nestle, Erwin, Nestle, and Kurt, Aland (eds.), Novum Testamentum Graece (25th ed.; Stuttgart, 1963), p. 71*.Google Scholar

page 388 note 5 Sanders, H. A. (ed.), The Washington Manuscript of the Freer Gospels (‘The New Testament Manuscripts in the Freer Collection’, vol. 1 [New York: The Macmillan Company, 1912])Google Scholar. See also Sanders, H. A. (ed.), Facsimile of the Washington Manuscript of the Four Gospels in the Freer Collection (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1912).Google Scholar

page 388 note 6 Herbert, Thompson (ed.), The Gospel of John According to the Earliest Coptic Manuscript (London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt, 1924).Google Scholar

page 388 note 7 Vööbus, , op. cit. p. 218.Google Scholar

page 388 note 8 Thompson, , op. cit. p. xiv.Google Scholar

page 388 note 9 Victor, Martin and Rodolphe, Kasser (eds.), Papyrus Bodmer XIV–XV, Évangiles de Luc et Jean (Geneva: Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, 1961)Google Scholar. The editors' note (vol. 11, p. 59) reads: ‘vers. 38 om. cf. intr. p. 28.’ There is, however, no mention of the omission in the introduction on page 28, or any-where else in the introduction.

page 388 note 10 ibid. 1, 13.

page 388 note 11 This relationship was established in the writer's article, ‘Papyrus Bodmer XV and the Text of Codex Vaticanus’, Journal of Biblical Literature, Lxxxi (1962), 363–76.Google Scholar

page 389 note 1 It is conceivable, although not likely, that a scribe might have objected to the use of προσκυνεīν with Jesus as object and hence omitted such a reference. This reasoning is incapable of explaining the omission of the words ![]() in verse 38 and καὶ είπεν ό 'ιησοῦς in verse 39.

in verse 38 and καὶ είπεν ό 'ιησοῦς in verse 39.

page 389 note 2 See Aland, , Black, , Metzger, , Wikgren, (eds.), op. cit. p. 365.Google Scholar This edition cites eight forms of the text of John ix. 36 and the textual support of each.

page 389 note 3 See ibid. p. 448. According to these editors' (Aland, Black, Metzger, Wikgren) scale (A, B, C, D), which indicates the relative degree of certainty for the reading adopted in their text, there is no doubt (A) that Acts viii. 37 is to be omitted. This edition cites the textual evidence for and against the omission.

page 390 note 1 It might be argued that a scribe omitted ix. 38, 39a from the text because it was out of harmony with Johannine theology. This does not explain the omission of all of verse 38 and the beginning words of verse 39. Moreover, scribes seldom, if ever, omitted sections from the text for the sake of preserving the integrity of the writer's theology.

page 390 note 2 The use of προσκυνεīν with Jesus as the object is infrequent in the Synoptic Gospels, except in Matthew. This usage occurs in Mark v. 6; xv. 19; Luke xxiv. 52 (v.1.); Matthew ii. 2; ii. 8; ii. 11; viii. 2; ix. 18; xiv. 33; xv. 25; xx. 20; xxviii. 9; xxviii. 17.

page 390 note 3 Brown, Raymond E., The Gospel According to John (i–xii) (‘The Anchor Bible)’, vol. 29 (Garden City: Doubleday & Co., Inc., 1966), p. cxiGoogle Scholar, writes: ‘Perhaps on no other point of Johannine thought is there such sharp division among scholars as there is on the question of sacramentalism. On the one hand, there is a group of Johannine scholars, including both Protestants (Cullmann, Corell) and Catholics (Vawter, Niewalda), who find many references to the sacraments in John. This sacramental evaluation of the Fourth Gospel has been popularized in France by Bouyer's commentary on John, and in America by D. M. Stanley in a series of articles in the Catholic liturgical magazine Worship. In general the British commentaries by Hoskyns, Lightfoot, and Barrett have shown themselves decidedly favorable to Johannine sacramentalism…On the other hand, there is another group of Johannine scholars who see no references to the sacraments in John. For some of these, the original Gospel was anti-sacramental. Among those who take a minimal view of Johannine sacramentality one may list Bornkamm, Bultmann, Lohse, and Schweizer, noting how-ever that their views vary widely.’

page 391 note 1 Adv. Haer. v. 15, 3.Google Scholar

page 391 note 2 De Sacramentis iii. 2, 8–15.Google Scholar

page 391 note 3 Tract. Joh. 44. 1, 2.Google Scholar

page 391 note 4 The Fourth Gospel and Jewish Worship (Oxford: At the Clarendon Press, 1960), p. 124Google Scholar. The work of Ephraim which she cites is Twelfth Rhythm on the Nativity.

page 391 note 6 De Sacramentis III. 2, 11Google Scholar, trans. Thompson, T., St Ambrose On the Sacrament and On the Mysteries, ed. Srawley, J. H. (rev. ed.; London: S.P.C.K., 1950), p. 77.Google Scholar

page 391 note 6 Jean le Théologien et son Évangile dans l'Église ancienne (Paris: J. Gabalda et Cie, 1959), pp. 149–5.Google Scholar For support Braun refers to the following works: Wilpert, G., Le Pitture delle Catacombe Romane (Rome, 1903)Google Scholar; Kirsch, J. P., Le catacombe romane (Rome, 1933)Google Scholar; Marucchi, O., Le Catacombe romane (Rome, 1933)Google Scholar; Styger, P., Die römischen Katakomben (Berlin, 1933)Google Scholar; Elliger, W., Zur Entstehung und frühen Entwicklung der altchristlichen Bildkunst (Leipzig, 1934).Google Scholar

page 391 note 7 A textual study of those sections of the text of John which were used, or had special significance, at an early date in various aspects of the life of the church would be interesting and could provide some insights into the earliest history of the text. See Edwyn Clement Hoskyns, The Fourth Gospel, ed. Francis Noel Davey (2nd ed.; London: Faber and Faber Ltd, 1947), Vol. II, Detached note 6, pp. 419–22.Google Scholar Hoskyns argues that since the episodes of the woman of Samaria, the paralytic, and the blind man appear in the second-century frescoes in the catacombs at Rome as baptismal symbols, the liturgical baptismal use of these episodes may have its roots in the second century. Such a study of these sections should also seek to determine if there is a greater degree of textual variation in these portions of the text than in those parts which were not used as frequently or had less significance for the life of the church.

page 392 note 1 Braun, F.-M., op. cit. pp. 158, 159.Google Scholar

page 392 note 2 Brown, Raymond E., op. cit. p. 380.Google Scholar It is interesting to note that the present Mass for the Wednesday after the fourth Sunday in Lent is the old scrutiny Mass. It refers to the effects of baptism in the introit and the two lessons (Ezek. xxxvi. 25, 26; Isa. i. 18), and alludes to the giving of the confession of faith (Traditio symboli) in the Gospel by the words of the man born blind, Credo, Domine.

page 393 note 1 The Apostolic Tradition 11. 21, 11–18, trans.Google ScholarScott Easton, Burton, The Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1934), pp. 46, 47.Google Scholar

page 393 note 2 Codex B and its Allies (London: Bernard Quaritch, 1914), part 11, p. 267.Google Scholar Presumably Hoskier referred to this lectionary as an explanation of the origin of ix. 38, 39a, although he does not say so.

page 393 note 3 Buck, Harry M. Jr, ‘The Johannine Lessons in the Greek Gospel Lectionary’ (Studies in the Leciionary Text of the Greek New Testament), vol. 11, no. 4 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1958), P. 1.Google Scholar

- 3

- Cited by