No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

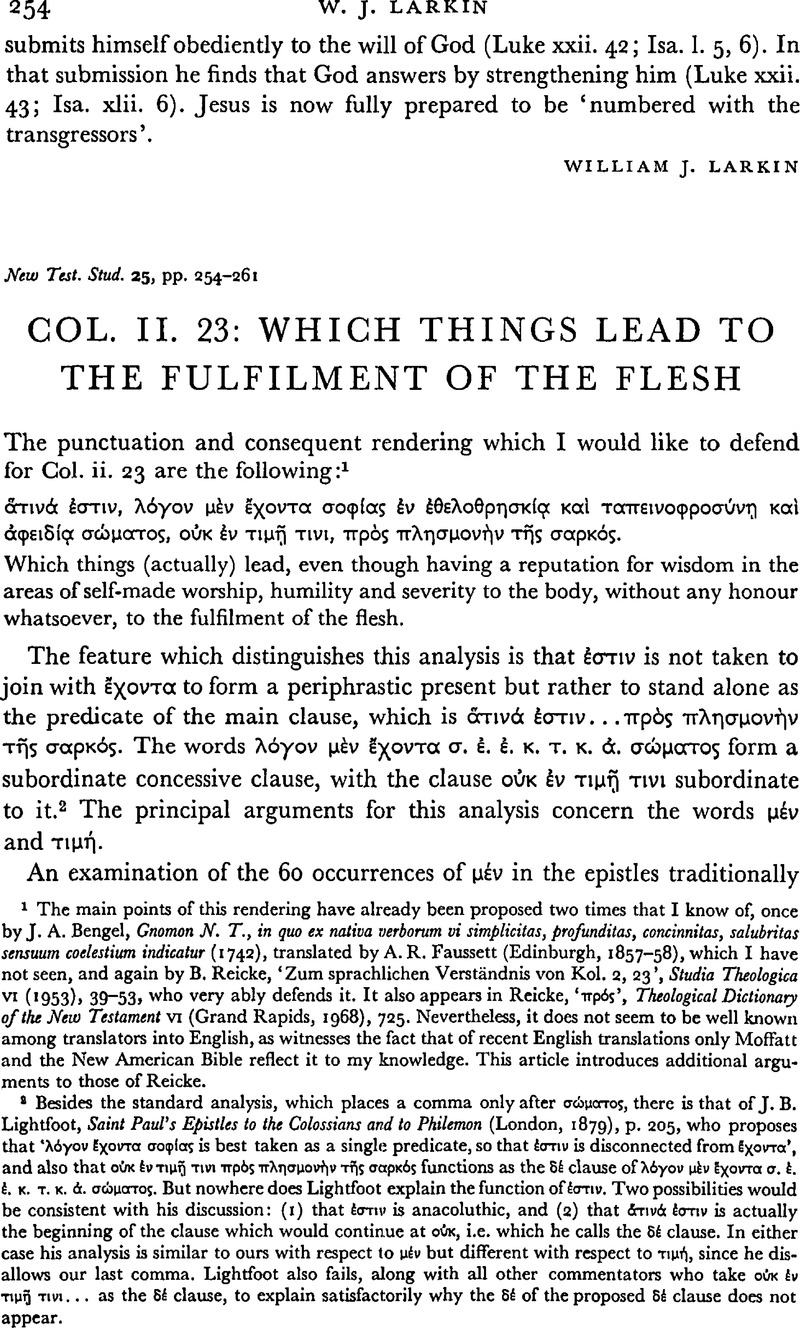

page 254 note 1 The main points of this rendering have already been proposed two times that I know of, once by J. A. Bengel, Gnomon N. T., in quo ex vertiva verborum vi simplicitas, prqfunditas, concinnitas, salubritas sensuum coelestium indicatur (1742), translated by A. R. Faussett (Edinburgh, 1857-58), which I have not seen, and again by 001 Reicke, B., ‘Zum sprachlichen Verständnis von Kol. 2, 23’, Studia Theologica vt (1953), 39–53Google Scholar, who very ably defends it. It also appears in Reicke, ‘πρδς’, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament vi (Grand Rapids, 1968), 725. Nevertheless, it does not seem to be well known among translators into English, as witnesses the fact that of recent English translations only Moffatt and the New American Bible reflect it to my knowledge. This article introduces additional arguments to those of Reicke.

page 254 note 2 Besides the standard analysis, which places a comma only after σώματος, there is that of Lightfoot, J. B., Saint Paul's Epistles to the Colossians and to Philemon (London, 1879), p. 205Google Scholar, who proposes that ‘λ⋯γον έχοντα σοφíας is best taken as a single predicate, so that ⋯στιν is disconnected from ⋯χοντα’, and also that οὐκ ⋯ν τιμῇ τινι πρ⋯ς πλησμον⋯ν τ⋯ς σαρκóς functions as the δ⋯ clause of λ⋯γον μ⋯ν έχοντα σ. ⋯. ⋯. κ. τ. κ. ⋯. σώματος. But nowhere does Lightfoot explain the function of ⋯στιν. Two possibilities would be consistent with his discussion: (1) that ⋯στιν is anacoluthic, and (2) that ⋯τιν⋯ ⋯στιν is actually the beginning of the clause which would continue at ο⋯κ, i.e. which he calls the δ⋯ clause. In either case his analysis is similar to ours with respect to μ⋯ν but different with respect to τιμή, since he disallows our last comma. Lightfoot also fails, along with all other commentators who take ο⋯κ ⋯ν τιμ⋯ τινι… as the δ⋯ clause, to explain satisfactorily why the δ⋯ of the proposed δ⋯ clause does not appear.

page 255 note 1 All occurrences are cited in the body of this paper. There are none in II Thess., I Tim., Titus, Philemon, and none in Colossians besides the one in question.

page 255 note 2 Reicke, op. cit. pp. 42–4, in his discussion of μ⋯ν includes two examples from Acts (iii. 13 and xxi. 39) which show respectively that a relative pronoun may precede a preposed contrasted item and that two items may be contrasted in the same clause, one occurrence of μ⋯ν marking both as contrastive. I do not know what all of the items which may precede a contrasted item are nor what their order of priority may be. Surely the verb is not one of them.

page 255 note 3 A parallel exception involving δ⋯ occurs in I Cor. xi. 7 ⋯ γυν⋯ δ⋯…, which violates the general tendency to place δ⋯ after the first word of the grammatical unit to which it pertains.

Some may interpret the variant reading in I Cor. ii. 15 ⋯ δ⋯ πνευματικ⋯ς ⋯νακρ⋯νει μ⋯ν π⋯ντα, α⋯τ⋯ς δ⋯ ὑΠ' οὐδεν⋯ς ⋯νακρ⋯νεται as an instance where δ⋯ν occurs in the fourth (or fifth?) position of the grammatical unit to which it pertains. This would be an incorrect analysis, since the contrast in this verse is not between the spiritual person and someone else but rather between judging and being judged and also between all things and no one. The presence of αὐτóς is to emphasize the contrast between the role of the ‘spiritual person’ as subject and his role as object of the judging. Therefore, we would translate: ‘And the spiritual person judges all things but is himself judged by no one.’

page 257 note 1 I am using the term ‘subordinate’ in a particularly semantic sense, referring less to the grammatical surface structure and more to the meaning underlying it. There is no feature of the grammatical surface structure of the three examples given here which would distinguish them as concessive structures from contrastive structures.

Possibly, the concessive use of μ⋯ν…δ⋯ is an extension of the contrastive use. As a matter of fact, although it is very difficult to arrive at a satisfactory definition of the relation of contrast, one promising possibility is that contrast is a mutual relation of concession between two predications (i.e. clauses), each being concessive to the other. It would follow that where a relation of contrast exists, the two predications would be interchangeable without changing the meaning, whereas where the relation of concession exists, one of the predications would be subordinate to the other and not interchangeable with it. This principle seems to be consistent with observed data.

page 258 note 1 Some of the citations given above as manifesting the contrastive use of μ⋯ν…δ⋯ could also be interpreted as concessive. Among these are: Rom. xi. 28; I Cor. ix. 24, xii. 20; II Cor. viii. 17, x. 10; Phil. ii. 23–24.

page 258 note 2 In particular, there is no precedent for interpreting τιμή to mean ‘value’ in the sense of ‘usefulness’ or ‘effectiveness’, as some have tried to do in this verse.

Lenski, R. C. H., The Interpretation of St Paul's Epistles to the Colossians, to the Thessalonians, to Timothy, to Titus and to Philemon (Columbus, 1946), p. 145Google Scholar, has faithfully rendered τιμή ‘price’ and suggested the following interpretation: ‘These things have a show of wisdom that is “not at all in connection with a certain price,” οὐκ ⋯ν τιμ⋯ τινι, which all these Judaizers are paying for what they really desire, a price “toward the satiation of the flesh.” This satiation is what they are really buying and making payments on.’ The rendering is reasonable but unsatisfactory, in that Lenski has had to supply too many of the key ideas himself. He registers his own dissatisfaction also.

page 259 note 1 The proposal of Lightfoot, op. cit. p. 206, that πρ⋯ς should be glossed ‘check, prevent, cure’ in this verse is to be taken seriously. His point is not weakened by saying that this interpretation depends upon the context, since the same is true of any interpretation of any preposition. Furthermore, II Cor. v. 12 is an excellent example of a similar usage to that which Lightfoot proposes: ίνα έχητε πρ⋯ς τοὺς… ‘so that you might have wherewith to counter those who…’. But I reject Lightfoot's overall analysis because of the unattested meaning required for and the general lack of coherence. (See above, p. 254 n. 2.)

Of less help is the interpretation by Leaney, R., ‘Col. ii. 21–23 (The use of πρ⋯ς)’, Exp. T. 64 (1952), 92Google Scholar, ‘but not of any value compared with actual indulgence of the flesh’, which, along with his gloss for πρ⋯ς ‘in comparison with’, would suggest that perhaps indulgence of the flesh can be given at least a mildly positive interpretation in this verse. But Leaney explicitly rejects this interpretation in his discussion, which I understand to suggest a rendering like, ‘but not of any value, just as indulgence of the flesh is of no value’. If this analysis of his argument is correct, then Leaney's appeal to Rom. viii. 18 ᾬξιος πρ⋯ς… as supporting evidence is seriously weakened, since the comparison in the latter is a relative comparison (i.e. ‘the coming glory is greater than the present sufferings’), whereas the comparison in Col. ii. 23 would be an absolute one (i.e. ‘in the sense that indulgence is of no value, so these commands are of no value, with no difference of degree’). And, of course, the statement that indulgence of the flesh is of no value could only be taken as extreme understatement coming from the apostle Paul. (See also Reicke, op. cit. p. 40.)

It has been fairly well established that it would not be consistent with Paul's theology to give πλησμον⋯ here any sort of positive or legitimate sense, even if it would help us out of any difficulties. (See Reicke, op. cit. pp. 39–40.)

page 259 note 2 We will not try to debate the interpretation of οὐκ ⋯ν τιμ⋯ here. My rendering ‘without any honour whatsoever’ is intended to communicate that the reputation is dishonourable, being unfounded. Reicke, op. cit. pp. 50–51, proposes ‘(but) without any (Christian) concern whatever (for the weaker brother)’ (my translation).

page 260 note 1 Reicke, op. tit. pp. 42–3, correctly recognize! that μ⋯ν cannot be functioning here as contrastive (‘correlative’), but unfortunately for the wrong reason, namely that no δ⋯ appears. (For a discussion of this problem, see below.) He is also unaware of the use of μ⋯ν to mark a concessive clause. Therefore, he concludes that μ⋯ν must be functioning as what has been called μ⋯ν solitarium, our positive-negative contrast. Lenski, op cit. p. 143, proposes the same interpretation. It would by no means obviate the necessity for the comma before λ⋯γον, since the word being contrasted must be first in its clause.

page 260 note 2 It was because of his inability to accept such a possibility that Meyer, H. A. W., Critical and Exegetical Handbook to the Epistles to the Philippians and Colossians and to Philemon (New York, 1885), p. 328Google Scholar, rejected the interpretation taken here, which he was aware had been proposed by Bengel.

page 261 note 1 See also Reicke, op. cit. pp. 52–3.