Article contents

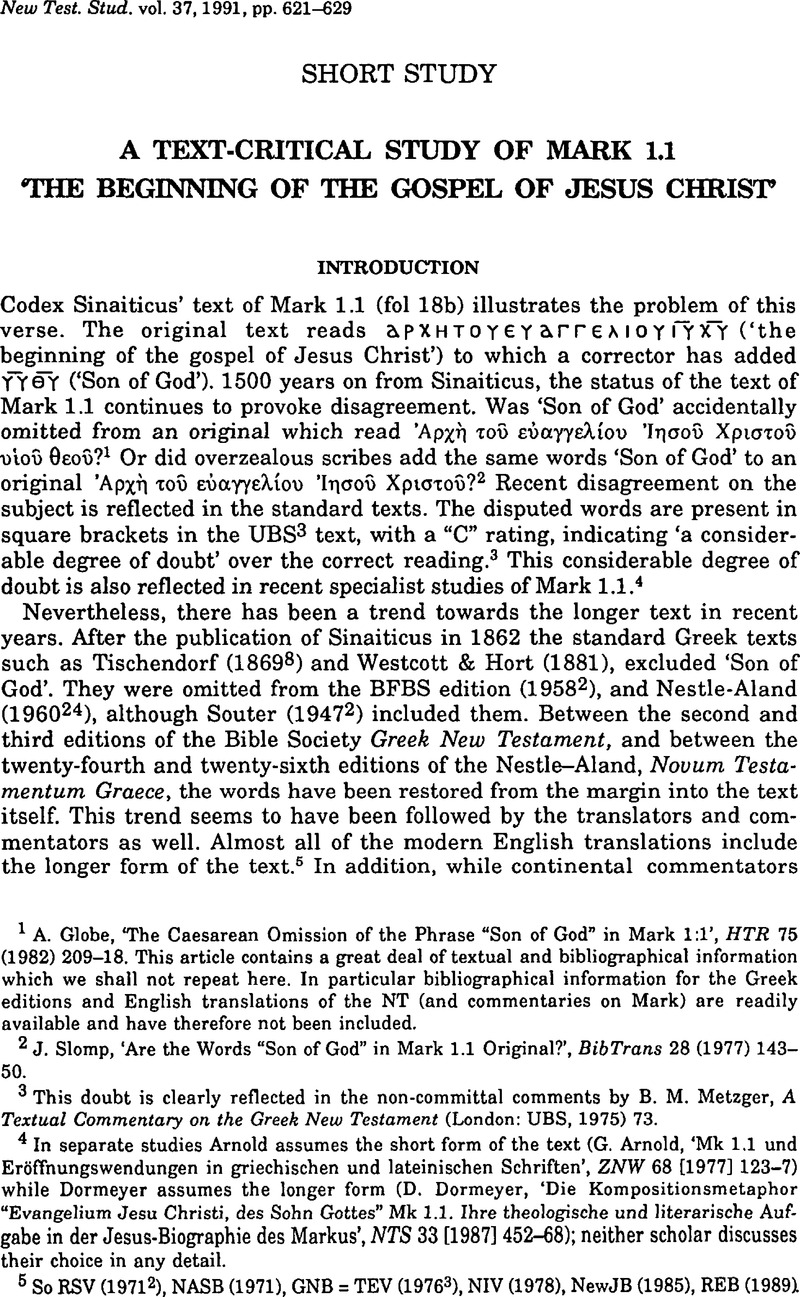

A Text-Critical Study of Mark 1.1 ‘The Beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ’

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Short Study

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1991

References

1 Globe, A., ‘The Caesarean Omission of the Phrase “Son of God” in Mark 1:1’, HTR 75 (1982) 209–18.Google Scholar This article contains a great deal of textual and bibliographical information which we shall not repeat here. In particular bibliographical information for the Greek editions and English translations of the NT (and commentaries on Mark) are readily available and have therefore not been included.

2 Slomp, J., ‘Are the Words “Son of God” in Mark 1.1 Original?’, BibTrans 28 (1977) 143–50.Google Scholar

3 This doubt is clearly reflected in the non-committal comments by Metzger, B. M., A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (London: UBS, 1975) 73.Google Scholar

4 In separate studies Arnold assumes the short form of the text (Arnold, G., ‘Mk 1.1 und Eröffnungswendungen in griechischen und lateinischen Schriften’, ZNW 68 [1977] 123–7Google Scholar) while Dormeyer assumes the longer form (Dormeyer, D., ‘Die Kompositionsmetaphor “Evangelium Jesu Christi, des Sohn Gottes” Mk 1.1. Ihre theologische und literarische Auf-gabe in der Jesus-Biographie des Markus’, NTS 33 [1987] 452–68Google Scholar); neither scholar discusses their choice in any detail.

5 So RSV (19712), NASB (1971), GNB = TEV (19763), NIV (1978), NewJB (1985), REB (1989).

6 B. Weiss (1901), Klostermann (1936), Lagrange (1947), Pesch (1976), Gnilka (1978), Lührmann (1987) include ‘Son of God’; Wellhausen (1903), Haenchen (1966), Schweizer (1967) omit. Lohmeyer (1953), Ernst (1963), and Grundmann (1968) are non-committal.

7 Gould (1896), Taylor (1952), Johnson (1960), Cranfield (1966), Lane (1974), Hendrickson (1975), Anderson (1976), Mann (1986), Guelich (1989). Swete (1909) and Nineham (1963) are non-committal.

8 Tischendorf (18698) cites only κ* 28, 255; C. H. Turner (1927) cites κ*Θ and ‘ two cursives’ (‘A Textual Commentary on Mark 1’, JTS 28 [1927] 150); Legg (1935) cites κ*Θ 28, 255, 1555, and the versions (syr, geo & arm as listed below). On the suggested identity of 255 and 1555 see Globe, ‘Omission’ 214 n 15.

9 In fact there are several other variants supported by only one witness. For example the reading of 1241 (XII Cent) Ίησο![]() Χριστο

Χριστο![]() υίο

υίο![]() το

το![]() κυρίου is a variant on the third reading; while the original reading of 28 (XI Cent) Ίησο

κυρίου is a variant on the third reading; while the original reading of 28 (XI Cent) Ίησο![]() was corrected by the scribe with Χριστο

was corrected by the scribe with Χριστο![]() and thus is a variant on reading one. The preface to the Arabic translation of Tatian's Dia-tessaron preserves an unusual form of Mark 1.1 (which does not appear to have been noticed in any critical apparatus): ‘The beginning of the gospel of Jesus, the Son of the living God’ [see Marmardji, A.-S., Diatessaron de Tatien (Beyrouth: Imprimerie Catholique, 1935] 2–3)Google Scholar.

and thus is a variant on reading one. The preface to the Arabic translation of Tatian's Dia-tessaron preserves an unusual form of Mark 1.1 (which does not appear to have been noticed in any critical apparatus): ‘The beginning of the gospel of Jesus, the Son of the living God’ [see Marmardji, A.-S., Diatessaron de Tatien (Beyrouth: Imprimerie Catholique, 1935] 2–3)Google Scholar.

10 UBS3 also quotes the Persian Diatessaron in favour of this reading, but this is inaccurate. To begin with there is no evidence that would associate its reading with the anarthrous form (as with the other versions). In addition the Persian Harmony is so far removed from Tatian that to label it as a Diatessaron is misleading. Indeed the fact that it begins with Mark 1.1 actually sets it apart from other witnesses to Tatian's Diatessaron (not to mention its totally different structural arrangement). The MS itself was copied in 1547 from an original of the thirteenth century (Messina, G., Diatessaron Persiano [Rome: PIB, 1951]).Google Scholar

11 There is little point in quoting references here; the point is not in dispute and, in any case, some references can be traced in Lampe, G. W. H., A Patristic Greek Lexicon (Oxford: Clarendon, 1961) 1427–8.Google Scholar

12 Space forbids a listing of these passages; references may be traced in Biblica Patris-tica: Index des citations et allusions bibliques dans la littérature patristique (ed. A. Benoit et al.; 3 vols.; Paris: CNRS, 1975, 1977, 1980, with a supplement on Philo, 1982).Google Scholar

13 For examples see Ep. Barn. 5.4; 7.9; Ignatius Ephesians 20.2; Smyrna 1.1; (cf. Romans insc: έν όνόματι Ίησο![]() Χριστο

Χριστο![]() υίο

υίο![]() πατρός); Justin Apol. 1.22, 30, 31, 54, 63, etc.; Irenaeus Adversus Haereses 1.9.3; Origen Contra Celsum 1.49, 57, 66, etc.; Athanasius, Expositions in Psalmos Ps LXVIII.17 (MPG 27 p. 309); Epistola catholica (MPG 28 p. 84); In passionem et cruce domini 23 (MPG 28 p. 225); Disputatio contra Arium 25 (MPG 28 p. 469); De sancta trinitate Dial V.5 (MPG 28 p. 1268); Gregory of Nyssa Adversus Arium et Sabellium de patre et filio (W. Jaeger ed.; Gregorii Nysseni opera vol. 3.1, p. 72); Epi-phanius Panarion 30.9.3 (GCS 25 p. 344). I was greatly helped in this investigation by the Ibycus Scholarly Computer (owned by Tyndale House, Cambridge, UK); this machine searches the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (a database of Greek literature, see further Berkowitz, L. & Squitier, K. A., Thesaurus Linguae Graecae. Canon of Greek Authors and Works [NY & Oxford: OUP, 1986]).Google Scholar

πατρός); Justin Apol. 1.22, 30, 31, 54, 63, etc.; Irenaeus Adversus Haereses 1.9.3; Origen Contra Celsum 1.49, 57, 66, etc.; Athanasius, Expositions in Psalmos Ps LXVIII.17 (MPG 27 p. 309); Epistola catholica (MPG 28 p. 84); In passionem et cruce domini 23 (MPG 28 p. 225); Disputatio contra Arium 25 (MPG 28 p. 469); De sancta trinitate Dial V.5 (MPG 28 p. 1268); Gregory of Nyssa Adversus Arium et Sabellium de patre et filio (W. Jaeger ed.; Gregorii Nysseni opera vol. 3.1, p. 72); Epi-phanius Panarion 30.9.3 (GCS 25 p. 344). I was greatly helped in this investigation by the Ibycus Scholarly Computer (owned by Tyndale House, Cambridge, UK); this machine searches the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (a database of Greek literature, see further Berkowitz, L. & Squitier, K. A., Thesaurus Linguae Graecae. Canon of Greek Authors and Works [NY & Oxford: OUP, 1986]).Google Scholar

14 On syrPal and 28 see , K. & Aland, B., The Text of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987) 195 and 129 respectively.Google ScholarPubMed

15 Burgon, J. W. & Miller, E., The Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels Vindicated and Established (ed. Miller, E.; London: George Bell & Sons, 1896) 279–86Google Scholar; Globe, , ‘Omission’, 210f.Google Scholar

16 The discussion in III.16.3 in particular does seem to demand that the long reading was in Irenaeus' mind. UBS3 cites Irenaeus as support for υίο![]() θεο

θεο![]() but this is incorrect. Irenaeus quotes Mark 1.1 three times, twice (as above) he supports the longer reading (but only in passages preserved in Latin); once (see below on Against Heresies III.11.8) his Greek text supports the short reading. On UBS3 inaccuracy see Globe, , ‘Omission’ 21 off.Google Scholar

but this is incorrect. Irenaeus quotes Mark 1.1 three times, twice (as above) he supports the longer reading (but only in passages preserved in Latin); once (see below on Against Heresies III.11.8) his Greek text supports the short reading. On UBS3 inaccuracy see Globe, , ‘Omission’ 21 off.Google Scholar

17 References can be traced in Tischendorf, 18968 and Globe, , ‘Omission’, 211 n 6.Google Scholar

18 Comm. on John 1.13 (in this place he quotes from 1.1–3); 6.24; Contra Celsum 2.4. See Globe, , ‘Omission’, 213Google Scholar. Some scholars attempt to conflate the witnesses of Sinaiticus and Origen (see Turner, ‘Text’, 150; Lane, Mark, 41 n. 7).

19 Serapion's Against the Manichees. See Globe, , ‘Omission’, 213–14 & n.Google Scholar 13 on the interpolation of this text into the text of Titus of Bostra's works. In the past Titus' work has been quoted in favour of the short reading. In effect it is simply another MS of Serapion and not an independent witness.

20 Burgon, , Traditional Text, 284f.Google Scholar n. 3; Turner, , ‘Text’, 150Google Scholar; Globe, , ‘Omission’, 212.Google Scholar

21 Commentary on the Apocalypse 4. 4 (see Globe, 212 n. 9 for editions), the omission of v. 2b could be due to some embarrassment due to the fact that v. 2b comes from Malachi; thus Victorinus' text clears up a difficulty felt by others in the early period.

22 Against Eunomius 2.15 (MPG 29 p. 601). In the previous section he omits ‘son of Abraham’ from Matthew 1.1.

23 Panarion 51.6.4 (GCS 31 p. 255).

24 The short reading occurs at Comm. Malachi 3.1 and Epistle to Pammachius (100) 57.9. The long reading (as well as occurring in the Vulgate) is found in his comments on Matt 3.3.

25 De sigillis librorum 5 (MPG 63 p. 541). See Hort, , ‘Notes on Select Readings’ in Westcott and Hort, The New Testament in the Original Greek 2 (London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1896 2-©1881) 23.Google Scholar

26 Bengel, J. A., H Καινη Διαθηκη. Novum Testamentum Graecum (Tübingen: I. G. Cottae, 1734) 433.Google Scholar

27 See Turner, ‘Text’, 150 for an example of this: ‘it is … infinitely more probable that in two early authorities ΥΥ ΘΥ had dropped out after IY XY than that the majority of good texts (including B and D) are wrong in retaining words which correspond so entirely to the contents of the Gospel…’. For the reverse see Tischendorf's comment: ‘Ineptum certe totique textus sacri historiae repugnans foret, tale quid potius modica fide sublatum quam pietate male sedula illatum dicere’ [= ‘It would be absurd and certainly against the history of the whole sacred text to say that such words would more likely be removed by modest faith, than be inserted by overzealous piety’, ET from Slomp, ‘Original?’, 146].

28 Other passages such as 8.38; 12.6; 13.32; 14.36 are sometimes added to this list.

29 This is not a quotation, but a summary of the arguments of: Taylor, , Mark, 152Google Scholar; Turner, , ‘Text’, 150Google Scholar; Globe, , ‘Omission’, 217Google Scholar; Cranfield, , Mark, 38Google Scholar; Bieneck, J., Sohn Gottes als Christusbezeichnung der Synoptiker (AbhTANT 21; Zurich: Zwingli-Verlag, 1951) 35.Google ScholarLane, , Mark, 41 n.Google Scholar 7 argues that ‘Jesus Christ, Son of God’ indicates the general plan of the book corresponding to 8.29 and 15.39).

30 Stonehouse, N. B., The Witness of Matthew and Mark to Christ (London: Tyndale, 1944) 12.Google Scholar

31 No single edition contains the evidence cited here. On Matt 1.1 and 1.16 see Legg, Euangelium secundum Matthaeum; on Matt 13. 37; John 1.18 and 6.69 see N-A26; on Mark 14.61 see Aland, Synopsis Quattuor Evangeliorum.

32 Especially in the Western text of Luke-Acts, the Syriac versions, and common in the Pauline epistles (see Zuntz, G., The Text of the Epistles [London: British Academy, 1953] 182f.Google Scholar

33 The quotation is from Williams, C. S. C., Alterations to the Text of the Synoptic Gospels and Acts (Oxford; Blackwell, 1951) 5.Google Scholar

34 Globe, , ‘Omission’, 217.Google Scholar Rather he might be expected to follow Attic usage and use an article or two.

35 Royse, J. R., ‘Scribal Habits in the Transmission of New Testament Texts’ in The Critical Study of Sacred Texts (ed. O'Flaherty, W. D.; Berkeley Religious Studies Series, 1979) 139–61.Google Scholar

36 For this argument see inter alia Globe, , ‘Omission’, 216–17Google Scholar, Cranfield, Taylor, Guelich, Pesch. Many scholars refer to omission through scribal error without explicitly mentioning homoioteleuton, so Klostermann, Lane, Turner ‘Text’, 150; Bieneck, Sohn Gottes, 35. While deliberate omission is occasionally suggested (by Martin, R. P., Mark: Evangelist and Theologian [Exeter: Paternoster, 1972) 27Google Scholar, Cranfield and referred to by Globe, , ‘Omission’, 216 n. 23Google Scholar) no evidence has been adduced in favour of this assertion. Such deliberate alteration would stand in stark contrast to the scribal tendencies we have previously observed.

37 O'Callaghan, J., ‘Nomina Sacra’ in Papyris Graecis Saeculi III Neotestamentariis (AnBib 46; Rome: BIP, 1970)Google Scholar defines as follows: ‘“Nomina sacra” are those words which primarily refer to God or divine persons, and secondarily, by participation or connexion, also to other created realities’ (p. 25).

38 Traube, L., Nomina Sacra. Versuch einer Geschichte der christlichen Kürzung (Quellen und Untersuchungen zur lateinischen Philologie des Mittelalters 2; Munich, 1907)Google Scholar is the standard work, supplemented by Paap, A. H. R. E., Nomina Sacra in the Greek Papyri of the First Five Centuries A.D. The Sources and Some Deductions (Papyrologica Lugduno-Batave 8; Leiden: Brill, 1959).Google Scholar See Traube, 125 and Paap, 123–6 for the points raised.

39 From Metzger, Text, 18. In what follows I am expanding a point made briefly by Slomp, ‘Original?’, 148.

40 Thanks are due to Messrs R. Watts and B. Rosner of Australia and Cambridge for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper, and to Indiginata Theological Consultancy Inc. for support.

- 4

- Cited by