1. Introduction

The word “discourse” is derived from the Latin prefix dis- meaning “away” and the root word currere meaning “to run”, and according to word etymology, the discourse describes thoughts in words, responsible for the interpretation of the communicative events in context (Nunan Reference Nunan1993). Discourse analysis comprises a dynamic notion that embraces various linguistic components of texts (morpho-lexical, syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic), as well as paralinguistic and extralinguistic components (punctuation, prosody, paragraphing, links to the contextual setting, short- and long-term memory) (DuBois Reference DuBois2003). As claimed by Hovy (Reference Hovy1993b), the content of a speaker’s discourse derives from different sources, and a surface-level structure is required to comprise them all. The major sources for the content of discourse are the semantics of the message, the interpersonal speech acts, the “control” information included by the speaker to assist the hearer’s understanding (namely, information signaling theme, focus, and topic), and knowledge about stylistic preferably (Grosz Reference Grosz1987). Considering this scenario, the very assumption underlying the definition of discourse may be applied in different areas. Indeed, discourse analysis comprises concerns across humanities and social sciences (Fairclough Reference Fairclough2003), besides computer science, more specifically the artificial intelligence (AI) dealing with its sub-area called computational linguistics (CL) (Braud et al. Reference Braud, Hardmeier, Li, Loaiciga and Zeldes2020, Reference Braud, Hardmeier, Li, Louis and Strube2021, Reference Braud, Hardmeier, Li, Louis, Strube and Zeldes2022; Strube et al. Reference Strube, Braud, Hardmeier, Li, Loaiciga and Zeldes2023; Fawcett and Davies Reference Fawcett and Davies1992; Hovy Reference Hovy1993a; Jurafsky and Martin Reference Jurafsky and Martin2009; Androutsopoulos, Lampouras, and Galanis Reference Androutsopoulos, Lampouras and Galanis2013; Trnavac, Das, and Taboada Reference Trnavac, Das and Taboada2016, Rohde et al. Reference Rohde, Johnson, Schneider and Webber2018; Fawcett and Davies Reference Fawcett and Davies1992).

In AI literature dealing with CL, Jurafsky (Reference Jurafsky2020) argues that language does not normally consist of isolated and unrelated sentences, but instead, it is a collocated, structured, coherent group of sentences. Moreover, a coherent structured group of sentences is named discourse. Ramsay (Reference Ramsay2005) defines discourse in CL as an extended sequence of sentences produced by one or more people to convert or exchange information. According to Moore and Wiemer-Hastings (Reference Moore and Wiemer-Hastings2003), the models of discourse structure and processing are crucial for constructing computational systems capable of interpreting and generating natural language. The authors also argue that discourse research in CL and AI encompasses spoken and written discourse, monologues, and dialogue (both spoken and keyboarded), and the context created by prior utterances affects the current one regardless of which participant uttered it. Lastly, research on discourse focuses on two fundamental questions within CL and AI. First, what information is contained in extended sequences of utterances that go beyond the meaning of the individual utterances themselves? Second, how does the context in which an utterance is used affect the meaning of the individual utterances or parts of them (Moore and Wiemer-Hastings Reference Moore and Wiemer-Hastings2003)?

Ramsay (Reference Ramsay2005) suggests that discourse-aware models must be built incrementally. For example, a wide range of discourse sentences accomplishes reference to concepts of the world, which were already known to the reader in the discourse. The incremental function of natural language to knowledge construction provides benefits to referring expressions for following tasks. These tasks are issues into CL related to discourse-level phenomena, such as (i) anaphora, which even though there is notoriously difficult to find a definition, according to Castagnola (Reference Castagnola2002), consists of a reference to entities mentioned previously in the discourse; pronouns, which are used to refer to items that have been mentioned very recently, and also it may be recognized based on very simple characteristic properties; (ii) coreference (also called co-reference), defined by Jurafsky and Martin (Reference Jurafsky and Martin2009) as two noun phrases that refer to the same entity, and coreference resolution, hence, is the task of identifying the sets of noun phrases that refer to the same entity; (iii) theme, according to Halliday (Reference Halliday1995), consists of a sentence as its first phrase, being the rheme the remainder; (iv) rheme consists of an element responsible for providing the cohesion of a sentence as a communicative whole Bussmann (Reference Bussmann1998); (v) topic and (vi) focus, such as claimed by Ramsay (Reference Ramsay2005), are different devices than theme and rheme, although they achieve similar effects, mainly if we consider intonation (or its typographical equivalents); (vii) presupposition and (viii) entailment are types of inference. Presupposition presents a wide range of computational and linguistic proprieties not exhibited by the general class of inferences (Mukherjee and Joshi Reference Mukherjee and Joshi2013). On the other hand, recognizing textual entailment requires automated systems to identify when two spans of text share a common meaning; (ix) implicature (also called conversational implicature) is a pragmatic concept introduced by British philosopher (Grice Reference Grice1975), which showed how meaning expressed by the speaker (speaker meaning) in conversation, not directly encoded in the words, maybe inferred (recognized) by the hearer; (x) discourse coherence, as defined by Jurafsky (Reference Jurafsky2020), consists of a coherent structured group of sentences, in which the word “coherence” is used to refer to the relationship between sentences that makes real discourses different than just random assemblages of sentences. Furthermore, according to Mann et al. (Reference Mann, Matthiessen and Thompson1992), theories of discourse coherence, which were broadly defined as “the sense of overall unity of a text,” are often used as descriptive tools in the analysis of coherence.

Discourse and pragmatic literature have been providing a set of frameworks in natural language processing (NLP), such as discourserepresentation structure, which consists of a set of discourse referents—corresponding to the set of individuals mentioned in the sentence being interpreted—and a set of conditions which are propositions involving those referents. In addition, the penn discourse treebank (PDTB) (Prasad et al. Reference Prasad, Dinesh, Lee, Miltsakaki, Robaldo, Joshi and Webber2008), is a discourse framework proposed on the simple idea that discourse relations are grounded in an identifiable set of explicit words or phrases (discourse connectives) or simply in sentence adjacency, has been taken up and used by many researchers in the NLP community and more recently, by researchers in psycholinguistics as well. As claimed by Jurafsky (Reference Jurafsky2020), PDTB consists of labeling corpus lexical-aware grounded composed of annotation of discourse coherence between text spans; they were given a list of discourse connectives, words that signal discourse relations, such as like, because, although, when, since, or as a result, among others. Finally, the most common discourse organization framework used in CL (Jurafsky Reference Jurafsky2020), the rhetorical structure theory (RST) (Mann and Thompson Reference Mann and Thompson1987), is defined as a theory to help us understand texts as instruments of communication. The RST consists of a discourse framework for investigating relational propositions, which are unstated but inferred propositions that arise from the text structure in the process of interpreting texts (Mann and Thompson Reference Mann and Thompson1987). Although there is a lack of comprehensive RST literature reviews, Vargas et al. (Reference Vargas, D’Alessandro, Rabinovich, Benevenuto and Pardo2022) proposed a survey on RST applied to fake news and fake reviews detection, and Hou et al. (Reference Hou, Zhang and Fei2020) provided an RST comprehensive review, in which theory, parsing methods, and applications are well-discussed and presented.

Lastly, as claimed by Passonneau and Litman (Reference Passonneau and Litman1997), natural language systems rarely exploit discourse structure, and cultural devices due to scarce consideration in the development of data resources and methods concerning diferrent languages. This predominance results in a lack of research and advances for low-resource languages (LRLs), as well as a lack of linguistic diversity. To fill this relevant gap, we introduce the first discourse annotation guideline using the RST framework for LRLs. We also present a summarized survey that comprises the main definitions concerning discourse in AI dealing with CL and discuss theoretical aspects related to the RST framework. Specifically, our guideline describes 24 (twenty-four) discourse coherence relations in three romance languages: Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish.

2. Low-resource languages

According to Khan et al. (Reference Khan, Ullah, Alharbi, Alferaidi, Alharbi, Yadav, Alsharabi and Ahmad2023), natural languages may be classified into two main categories: LRLs and high-resource languages (HRLs). More broadly, HRLs consist of languages with a wide range of available data resources that enable machines to learn and understand natural languages. For instance, English is a well-resourced language as compared to other spoken languages (Khan et al. Reference Khan, Ullah, Alharbi, Alferaidi, Alharbi, Yadav, Alsharabi and Ahmad2023). On the other hand, LRLs consist of languages with scarce or no resources available, which is defined by Cieri et al. (Reference Cieri, Maxwell, Strassel and Tracey2016) as less studied, resource-scarce, less computerized, less privileged, less commonly taught, or low-density languages. For instance, most of the European languages are severely under-resourced (Khan et al. Reference Khan, Ullah, Alharbi, Alferaidi, Alharbi, Yadav, Alsharabi and Ahmad2023). Furthermore, Latin American languages including indigenous languages are also considered under-resourced languages.

According to Cieri et al. (Reference Cieri, Maxwell, Strassel and Tracey2016), terms such low density, less commonly taught, under-resourced, less resourced, and low resource are commonly used to refer to LRLs. For instance, low density consists of languages with few online or computational data resources exist (Megerdoomian and Parvaz Reference Megerdoomian and Parvaz2008). Differently, less commonly taught are world languages that are underrepresented in the education system.Footnote a Lastly, the terms under-resourced,less resourced, or low resourceseem to have similar means by literature.

In addition, LRL is also defined via the metric of Gross Language Product (Wiemerslage et al. Reference Wiemerslage, Silfverberg, Yang, McCarthy, Nicolai, Colunga and Kann2022). It is the product of the number of native speakers of the language in any country and the country’s per capita Gross National Product. Notice that this definition suffers influence from the social-political and economic context of language once that “low” definition is most likely to be relative to some expectation based on the “importance” of the language (Megerdoomian and Parvaz Reference Megerdoomian and Parvaz2008).

Finally, It is a well-known fact that the LRLs are neglected in NLP literature. As a result, most discourse-aware data resources are produced in English. Hence, we introduce the first discourse guideline using RST for LRLs. Specifically, this guideline provides examples of RST coherence relations in three different romance languages: Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish.

3. RST annotation guideline

Here, we introduce the first discourse annotation guideline using RST focused on LRLs. This guideline focuses mainly on Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish. We used three different datasets: (i) DETESTSFootnote b (Ariza et al. Reference Ariza-Casabona, Schmeisser-Nieto, Nofre, Taulé, Amigó, Chulvi and Rosso2022) composed of comments in Spanish from news articles segmented into 5,629 sentences containing hate speech against immigrants; (ii) DeceiverFootnote c (Vargas et al. Reference Vargas, Benevenuto and Pardo2021) composed of 600 news articles and fake news in Portuguese and English; and (iii) Italian-RST-NewsFootnote d extracted from relevant media outlets in Italy, as well as the Wikipedia.it. Note that we extracted examples from datasets in different languages and domains (e.g., news articles, fake news, and hate speech comments containing stereotypes) in order to show the feasibility of the RST framework to be applied in different languages, domains and discourse structures. Nevertheless, each language and domain present its challenges, mainly the domain of web comments due to different noise and grammar and/or vocabulary errors or inadequacies, and idiosyncrasies. Hence, we aim to provide a well-defined and structured discourse guideline to support researchers and annotators to annotate discourse structure using RST in different languages and domains.

The RST was originally proposed for computer-based authoring and natural language generation; however, this powerful framework has been used ever since in a wide variety of NLP tasks. RST is a descriptive theory of a major aspect of the organization of natural text. It is a linguistically useful method for describing natural texts, characterizing their structure primarily in terms of relations that hold between parts of the text (Mann and Thompson, Reference Mann and Thompson1987). Also, it provides a model that represents a document as a tree of discourse units recursively built by connecting smaller units through rhetorical relations (Mabona et al. Reference Mabona, Rimell, Clark and Vlachos2019). Furthermore, according to Mann and Thompson (Reference Mann and Thompson1987), the fundamental mechanisms to annotate text and generate RST trees are segmentation, nuclearity, schemas, and structures (coherence relations), described as follows.

3.1 Segmentation

Text segmentation is a fundamental task in NLP. In RST, there are two main definitions for text segmentation: text spans and elementary discourse unit (EDU)(Asher and Lascarides Reference Asher and Lascarides2023). A text span is an uninterrupted linear interval of text. On the other hand, an EDU is usually defined as minimal building blocks for forming a discourse tree, and it is mostly used to designate a minimal speech act or communicative unit, where each EDU corresponds roughly to a clause-level content that denotes a single fact or event (Prevot et al. Reference Prevot, Hunter and Muller2023). Furthermore, the discourse segmentation task consists of segmenting an uninterrupted linear interval of text into a sequence of EDUs (Li, Sun, and Joty Reference Li, Sun and Joty2018). Each utterance of an EDU contributes to the communicative relevance of the preceding utterances or constitutes the onset of a new unit of meaning or event that subsequent utterances may add to (Passonneau and Litman Reference Passonneau and Litman1997). In the same settings, discourse models as multiutterance EDUs and structural relations among them yield a discourse tree structure (Grosz and Sidner Reference Grosz and Sidner1986).

According to Hobbs (Reference Hobbs1979), segmental discourse structure is an artifact of coherence relations among utterances, such as elaboration, evaluation, cause, and so on. The EDU in RST is an atomic semantic unit, similar to a clause in a sentence, and may also be considered clause-like units that serve as building blocks for discourse parsing (Li et al. Reference Li, Sun and Joty2018). Although the types of discourse units being coded and the relations among them vary (Passonneau and Litman Reference Passonneau and Litman1997), to identify EDUs is necessary to classify the prominent and complementary text spans into a sentence or document according to the writer’s intention. For instance, we first should identify the most prominent and important text segment in the sentence, then, the most complementary text segment. As a result, the most prominent text segment is classified as the nucleus, and the complementary text segment is classified as the satellite.

3.2 Nuclearity

Nuclearity in RST consists of the identification of prominent and complementary EDUs classified as nucleus and satellite. Furthermore, the type of nuclearity is divided into mononuclear and multinuclear, as shown in Figure 1. Observe that the nucleus consists of EDUs that are more central and relevant in the text. Differently, the supporting EDUs are named satellites.

Figure 1. Nuclearity structure in mononuclear and multinuclear discourse coherence relations.

3.3 Schema

According to Mann and Thompson (Reference Mann and Thompson1987), a schema may be defined as predefined patterns specifying how regions of text combine to form larger regions, up to whole texts. In Figure 2, we show five different types of schemas originally proposed by RST’s authors. Observe that a schema based on the RST framework is characterized by a vertical line pointing to one of the text spans that the schema covers called the nucleus. The other spans are linked to the nucleus by relations, represented by labeled curved lines, and these spans are called satellites.

3.4 RST coherence relations

The RST predicts a tree of coherence relations (also known as rhetorical or discourse relations), mainly based on the premise that the content of text units may be hierarchically organized. Accordingly, it predicts that some units are more central (salient) to the text than others, as well as that the other units support the text message. In this RST annotation guideline for LRLs, we describe in detail 24 (twenty-four) coherence relations proposed originally by RST manuscript (Thompson and Mann Reference Thompson and Mann1988). We highlight each of them in Sections 3.4.1–3.4.24.

Figure 2. Types of schemes.

Table 1. Antithesis relation constraints

3.4.1 ANTITHESIS

According to linguistics studies, antithesis is defined as a figure of speech characterized by the simultaneous use of terms, words, or sentences that are opposed to the meaning. For example, in “truth and lies are part of everyday life,” the terms truth and lies form an antithesis construction due to opposition of meaning between the terms used to create an effect on the reader. In general, most figures of speech are used to create particular potential effects on the reader. According to Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017), define the antithesis discourse coherence relation as a relationship in which the writer regards the content of the nucleus as more important. In addition, this relation is rarely signaled by connectives, and the situation presented in the nucleus is found in contrast with the situation presented in the satellite. The contrast may happen in only one or a wide range of respects. Also, it is always mononuclear—it is a counteractive relation that distinguishes clearly between the nuclearity of its arguments (Carlson and Marcu Reference Carlson and Marcu2001). Table 1 describes the definitions in terms of constraints on the nucleus, satellite, and the combination of both for the antithesis relation. Notice this relation presents information intentionally informed and it is always mononuclear. In addition, there is one constraint on the nucleus, but there are no constraints on the satellite. In the nucleus, the writer judges the nucleus as valid. Lastly, the effect on the reader consists of the reader accepting the nucleus better than the satellite. Figures 3, 4, and 5 show examples of the antithesis relation.

Observe that the nucleus presents information of which the author is more favorable than information presented in satellite. In addition, the nucleus and satellite are both in contrast, and the reader accepts the nucleus better than the satellite. Finally, a final statement is not less important than previous statements.

Figure 3. Antithesis relation in Spanish.

Figure 4. Antithesis relation in Portuguese.

Figure 5. Antithesis relation in Italian.

Table 2. Background relation constraints

Figure 6. Background relation in Spanish.

Figure 7. Background relation in Portuguese.

Figure 8. Background relation in Italian.

3.4.2 BACKGROUND

Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) define the BACKGROUND relation as a type of coherence relation that settles a relationship between the nucleus and the satellite, in which the understanding of the satellite makes it easier for the reader to understand the content of the nucleus. Therefore, it would be difficult to comprehend the nucleus without the “background” information provided by the satellite. Furthermore, the satellite, mostly but not always, precedes the nucleus, and the satellite at the beginning of the text often serves to introduce the topic of the text. Furthermore, Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001) claim that the satellite is responsible for providing the context of use or the grounds concerning which the nucleus is to be understood. In this case, understanding the satellite helps the reader understand the nucleus. Also, the satellite is not the cause/reason/motivation of the situation presented in the nucleus, and the reader/writer’s intentions are irrelevant in determining whether such a relation holds. Finally, the background is rarely signaled by connectives (Stede et al. Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017). In Table 2, we describe the definitions for the background relation. Notice it is a mononuclear relation and presents intentional information. The nucleus presents information that must be understood from the information described in the satellite. There are no constraints on the satellite. Therefore, the satellite improves the reader’s ability to understand the nucleus. On the effects on the reader, the reader understands better the nucleus from the reading of satellites. Figures 6, 7, and 8 show examples of backgroundrelation. Observe that the nucleus presents the information more prominent. Nevertheless, the information presented in satellites is relevant to understanding the nucleus. In other words, without the information presented in the satellite, the reader would not understand properly the information presented in the nucleus.

3.4.3 CIRCUMSTANCE

According to linguistic studies, the circumstantial meanings would be analyzed from different perspectives. In Martin (Reference Martin1992), the authors studied the circumstantial meanings from a discourse semantic perspective that would be related to the proposed term “setting,” which refers to mainly locational circumstantial meanings. Nevertheless, as claimed by Dreyfus and Bennett (Reference Dreyfus and Bennett2017), it is separated from the type of circumstantial meaning from the type of lexico-grammatical structure that realizes that meaning. For instance, the sentence “I went to the union that hot Friday.” In this sentence, it is possible to note a type of circumstantial meaning related to locational circumstantial meanings. On the other hand, the sentence “Lunchtimes on Friday are always busy in this cafe” provides a type of lexico-grammatical structure related to qualifier circumstantial meanings. More broadly, the circumstantial meaning is a region of ideational meaning that is instantiated across a range of lexico-grammatical structures: from the rank of the clausal constituent of circumstance in both directions up to clause rank and down to below or within constituent rank (e.g., as qualifier) (Dreyfus and Bennett Reference Dreyfus and Bennett2017). Shortly, this last one proposes the circumstantial meaning within the discourse semantic system of ideation (Martin Reference Martin1992).

Table 3. Circumstance relation constraints

According to Mann and Thompson (Reference Mann and Thompson1987), the circumstance relation, holds between two parts of a text if one of the parts establishes a circumstance or situation, and the other part is interpreted within or relative to a framework (e.g., a temporal or spatial framework). Moreover, Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) define it as a type of relationship between the nucleus and satellites, in which the satellite supplies necessarily an event or state that occurs or has occurred; therefore, it is not a hypothetical one. Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001) argue that the presented situation in the satellite provides the context of which the presented situation in the nucleus should be interpreted. In addition, it is always mononuclear, and selecting the circumstance relation over the background relation when the events are described in the nucleus and satellite is somewhat co-temporal. Considering a comparative analysis between the circumstance and background, the information or the context of the background is not always specified clearly or delimited sharply. Also, the events represented in the nucleus and the satellite occur at distinctly different times. The events in a circumstance relation are somewhat co-temporal (Carlson and Marcu Reference Carlson and Marcu2001). Lastly, the typical connectives found in the circumstancerelation are “as”, “when”, and “while” (Stede et al. Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017). Table 3 describes the definitions for circumstance relation. Notice it is a mononuclear relation, which presents semantic information without constraints on the nucleus. Furthermore, the satellite must present a situation realized, and the satellite necessarily provides a situation in which the reader may interpret the nucleus. Finally, Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001) argue that in a circumstance relation, the satellite may not present any cause, reason, or motivation for the situation presented by the nucleus, and the reader/writer’s intentions are irrelevant to determine whether such a relation holds. Accordingly, as shown in Figures 9, 10, and 11, the presented situation in the satellite provided the context in which the presented situation in the nucleus must be interpreted.

Figure 9. Circumstance relation in Spanish.

Figure 10. Circumstance relation in Portuguese.

Figure 11. Circumstance relation in Italian.

3.4.4 CONCESSION

Historically, the notion of concession according to linguistic studies is associated with relations between the utterance segments that imply a contrast. Furthermore, its definition takes into account pragmatics and cognitive inferences. According to Kim (Reference Kim2001), the speaker asserts the propositions of the two related clauses in question against the background assumption that the two types of situations are generally incompatible. (e.g. “Even if Einstein tried to solve the math problem, he could not solve it.”). In RST, Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) define the concession relation, as a type of relationship between the nucleus and satellite, in which the writer regards the content of the nucleus as more important than the content presented by the satellite. Besides that, in comparison to the nucleus, the writer regards the content of the satellite as less important, even though the writer does not dispute that the satellite holds. In Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001), the concession is defined as a type of relationship in which the situation indicated in the nucleus is contrary to expectation in the light of the information presented in the satellite. In other words, it is always characterized by a violated expectation. Furthermore, the typical connectives are “although”, “but”, “and”, “despite”, “which”. Table 4 describes the definitions for the concession relation. Notice it is mononuclear and presents intentional information, with constraints on the nucleus and satellite. In addition, the writer judges the nucleus and the satellite despite them being incompatible. Figures 12, 13, and 14 shown examples of concession. Observe that the connective “but” (in Spanish: “perfo,” in Portuguese: “mas,” and in Italian “ma”) is an example of a discourse marker, or in other words, it is also a signal of concession relation. Accordingly, it would be agreed that these discourse markers may be considered as “clues” to identify RST coherence relations. Finally, as shown in Figures 12, 13, and 14, we also note an incompatibility between the satellite and the nucleus raises the reader’s ability to regard the nucleus, and such property distinguishes these discourse coherence relations from others.

Table 4. Concession relation constraints

Figure 12. Concession relation in Spanish.

Figure 13. Concession relation in Portuguese.

Figure 14. Concession relation in Italian.

Table 5. Condition relation constraints

3.4.5 CONDITION

Conditional sentences present two main parts: (i) the antecedent titled protasis and (ii) the consequent denomination titled apodosis. For instance, in the following example: “If you come closer, you’ll be able to see the parade”, the antecedent would be “if you come closer”, which consists of protasis, and the consequent “you’ll be able to see the parade”, would be the apodosis. Furthermore, Sweetser (Reference Sweetser1990) claims that conditional semantics has three distinct domains: (i) the content domain, which is understood by relating the content of the two clauses to each other, for example, if you drop it, it will break; (b) the epistemic domain, which is understood as expressions of the reasoning process (e.g. “if the streets are wet, it rained last night”); and (c) the speech act domain, which is understood as pre-posting to a speech act (e.g. “if you leave before I see you again, have a good time”). In RST, the condition relation may be defined as a relationship between the nucleus and satellite, in which the information associated with the nucleus must be a consequence of the achievement of the condition in the satellite (Mann and Thompson, Reference Mann and Thompson1987). In addition, Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001) suggest that the truth of the proposition associated with the nucleus is a consequence of the fulfillment of the condition in the satellite. Likewise, the satellite provides a situation that is not realized. Also, Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) claim that the satellite must present a hypothetical, future, or in other ways, unreal situation, and the realization of the nucleus depends necessarily on the realization of the satellite. Typically, this relation is signaled by connectives, such as “if&then”, and “in case”. Table 5 describes the definitions for the condition relation. Notice it presents only one nucleus and semantic information. There are also no constraints on the nucleus, and the satellite presents a hypothetical situation. Figures 15, 16, and 17 show examples of this relation. Observe that, in the condition relation, the nucleus presents a fact that may be performed whether the condition presented in the satellite will be performed. Even though all examples presented comprise the marker “if” (in Spanish: “si,” in Portuguese: “se,” and in Italian: “si”), according to Mann and Thompson (Reference Mann and Thompson1987), the condition relation does not necessarily need to be expressed with an “if” clause.

Figure 15. Condition relation in Spanish.

Figure 16. Condition relation in Portuguese.

Figure 17. Condition relation in Italian.

3.4.6 CONTRAST

Natural languages comprise sophisticated mechanisms capable of connecting information. This “connectors” are responsible for connecting sentences and establishing a coherent relation, and they are called conjunctions. In general, when any speaker wishes to connect contrastive information, a particular type of conjunction is employed. They are classified as adversative connectives or contrastive connectives, besides contrastive discourse markers, which are connectors of discourse units whose content refers to an “opposite” or “contradictory” (Fraser Reference Fraser1999). In RST, parts of texts whose relationship manifests semantically as an opposition must be classified as a contrast relation. The contrast relation provides a type of relationship between the nucleus and nucleus with exactly two nuclei being both of equal importance for the writer’s purposes (Mann and Thompson, Reference Mann and Thompson1987). Moreover, the contents are comparable but not identical, and they differ taking into account aspects that are important to the writer. According to Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001), the typical CONTRAST relation includes contrastive discourse markers such as “but”, “however”, “while”. In addition, Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) claim that discourse markers for the identification of this relation are “on the other hand”, “yet”, and “but”. In a summarized way, the contrast is a multinuclear relation, which establishes the relationship between the nucleus and nucleus to express an opposite thought. It contrasts with the previous thought, and typically at least a nucleus is introduced by adversative conjunctions. Table 6 describes the definitions for the contrast relation. Notice it presents two or more nuclei and semantic information. Furthermore, the contrast between text spans raises the ability’s reader to regard the contraction information present in the nucleus. Figures 18, 19, and 20 show examples of this relation. Observe that the facts presented in

Table 6. Contrast relation constraints

Figure 18. Contrast relation in Spanish.

Figure 19. Contrast relation in Portuguese.

the nucleus are in contrast, and there are discursive markers to identify this contrast. Nevertheless, contrastive sentences may occur without any discourse marker.

Figure 20. Contrast relation in Italian.

3.4.7 ELABORATION

The elaboration is a relation highly ambiguous. According to a study proposed by Marcu and Echihabi (Reference Marcu and Echihabi2002), the contrast and elaboration relations presented only 61 from 238 discourse markers (26 percent). Moreover, Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001) claim that this relation is extremely common at all levels of the discourse structure, and it is especially popular to show relations across large spans of information. In RST, in order to accurately identify the elaboration relation, the satellite must give additional information or detail about the situation presented in the nucleus (Carlson and Marcu Reference Carlson and Marcu2001). Furthermore, Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) define this relation as a relationship between the nucleus and satellites, in which the satellite provides details or more information on the state of affairs described in the nucleus. Lastly, Marcu (Reference Marcu2000) suggests that the elaboration relation may be used when none of the other relations is applied. According to Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017), typical connectives are “in particular” and “for example”. Table 7 describes the definitions for the elaboration relation. Note that this relation presents only a nucleus and semantic information beyond no constraints on the nucleus and satellite, and the satellite typically presents any additional information about the nucleus. Also, the reader’s ability to recognize additional information in a satellite that refers to the nucleus. Figures 21, 22, and 23 show examples of this relation. Observe that the satellite typically provides a qualification or specification of the nucleus, besides the adjective subordinate clauses, which are candidates to be an elaboration relation.

Table 7. Elaboration relation constraints

Figure 21. Elaboration relation in Spanish.

Figure 22. Elaboration relation in Portuguese.

Figure 23. Elaboration relation in Italian.

3.4.8 ENABLEMENT

According to linguistics studies, enablement sentences present possibilities or hypotheses. For instance, the particles “can” and “may” in general connect assumptions semantically organized to express a possibility and pragmatically intended to raise the reader’s belief that the fact is unrealizable. According to Mann and Thompson (Reference Mann and Thompson1987), the enablement relation provides information designed to increase the reader’s desire to act. Furthermore, Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) suggest that this relation is a genre of editorial, and also it is rarely found in other textual types, hence, it is difficult to identify. In RST, the enablement relation is defined as a nucleus responsible for presenting information on a situation that is unrealized. In addition, the action presented in the satellite increases the chances of the situation in the nucleus being realized (Carlson and Marcu Reference Carlson and Marcu2001). Table 8 describes the main definitions for the enablement relation in terms of constraints on the nucleus and satellite. Notice it presents only a nucleus; hence it is a mononuclear relation. Additionally, there are no constraints on the satellite, and the nucleus presents an action or fact that may be realized whether the possibility presented in the satellite is true. Finally, the reader’s ability to act as the nucleus is increased. Figures 24, 25, and 26 show examples of the enablementrelation. Observe that, as stated by Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017), the nuclei present an unrealized situation, and comprehending the satellite makes it easier for the reader to perform the action described in the nucleus.

Table 8. Enablement relation constraints

Figure 24. Enablement relation in Spanish.

Figure 25. Enablement relation in Portuguese.

Figure 26. Enablement relation in Italian.

3.4.9 EVALUATION

Subjective information or subjectivity in natural language refers to aspects of language used to express opinions, evaluations, and speculations (Wiebe et al. Reference Wiebe, Wilson, Bruce, Bell and Martin2004). Worldviews and points of view are built to evaluate situations, events, and objects in the world, and this information is analyzed at the discourse level. In RST, theevalulation relation provides subjective information. In other words, it must comprise a point of view, appraisal, estimation, rating, interpretation, or assessment of a situation. Therefore, each piece of subjective information is signaled by evalulation relation.

Table 9. Evaluation relation constraints

Figure 27. Evaluation relation in Spanish.

According to Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001), the evalulation relation is defined as a relationship between the nucleus and satellites, in which one span evaluates the situation presented in the other span of the relationship on a scale of good to bad. Besides, according to Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017), usually the “evaluating” segment follows the “evaluated” one, although sometimes the order is the opposite. Therefore, the evalulation relation occurs when the satellite typically presents any subjective information. Table 9 describes the definitions for the evalulationrelation. Notice it is mononuclear and presents semantic information. While there are no constraints on the nucleus and satellite, the satellite provides subjective content. Furthermore, the reader recognizes the subjective value of information in the satellite. Figures 27, 28, and 29 show examples of this relation. Observe that the satellites provide subjective information. Hence, toward identifying the EVALUATION discourse coherence relation, the satellite must necessarily take account of the point of view on the topic presented in the nucleus at a scale between bad and good.

Figure 28. Evaluation relation in Portuguese.

Figure 29. Evaluation relation in Italian.

Table 10. Evidence relation constraints

3.4.10 EVIDENCE

Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) define the evidence relation as a type of relationship between the nucleus and satellites, in which the nucleus presents a subjective statement or thesis or claim, whereby the reader might not accept or might not regard as sufficiently important or positive. Furthermore, the satellite must provide a statement that the reader is likely to accept. Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001) argue that it is a type of discourse coherence relation in which the satellite must present a situation that is responsible for providing any evidence or justification concerning the situation described in the nucleus. Additionally, the evidence relation pertains to actions and situations that are independent of the will of an animate agent. Also, the evidence is data on which judgment of a conclusion may be based and is presented by the writer or an agent in the article to convince the reader of a point. Lastly, the typical connectives are the causal connectives (Stede et al. Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017). Table 10 describes the definitions for evidence relation. Notice it is mononuclear and presents semantic information. Although there are no constraints on the nucleus and satellite, the relationship between satellites is performed through the writer’s subjective content. Furthermore, the reader recognizes the subjective value of information in the satellite, and also recognizes the intention of the writer to provide credibility to the information presented in the nucleus. Finally, according to Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017), this relation often provides connections between a larger satellite segment and a shorter nucleus. For instance, in evidence whose source is a thesis, as shown in Figures 30, 31, and 32. Observe that the satellite provides explicit information that serves as contestable or incontestable evidence to support information claimed in the nucleus. Furthermore, the EVIDENCE discourse coherence relation may also present statistical information.

Figure 30. Evidence relation in Spanish.

Figure 31. Evidence relation in Portuguese.

Figure 32. Evidence relation in Italian.

Table 11. Interpretation relation constraints

Figure 33. Interpretation relation in Spanish.

3.4.11 INTERPRETATION

Theinterpretation relation may be complex to identify. According to Mann and Thompson (Reference Mann and Thompson1987), this relation is mononuclear and may be defined as a type of relationship between the nucleus and satellite, in which the satellite relates the situation presented in the nucleus to a framework of ideas not involved in the nucleus itself and not concerned with the writer’s positive or negative regard. Moreover, it presents the satellite evaluating the knowledge presented by the nucleus in terms of the writer’s positive or negative regard. In the same settings, Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001) claim that to identify this relation one side of the relationship gives a different perspective on the situation presented in the other side. It is subjective, presenting the personal opinion of the writer or a third party. Additionally, Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) suggests that the nucleus precedes the satellite in the text, and the satellite shifts the content of the nucleus to a different conceptual frame. Besides, It should be pointed out that theinterpretation relation does not imply that threre is an evaluation of the nucleus (or the evaluation is of only secondary importance). Accordingly, toward identifying the interpretation relation, the reader must keep in mind that whenever the satellite primarily provides an assessment (on the positive/negative scale) of the nucleus, the evaluation relation is to be used, rather than interpretation. Lastly, the typical connective is “thus”. Table 11 describes the definitions for theinterpretation relation. Notice the content of the nucleus is presented to a different conceptual frame. This does not imply an evaluation of the nucleus (or the evaluation is of only secondary importance). Furthermore, on the report of Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017), the reader recognizes that the satellite relates the nucleus to a framework of ideas not involved in the knowledge presented in the nucleus itself. Figures 33, 34, and 35 show examples of the interpretation relation. Observe the expression of a viewpoint of the writer or another agent in the text is observed in this relation (Carlson and Marcu Reference Carlson and Marcu2001). We should like to reiterate that the interpretation relation presents high ambiguity with the evaluation relation. Therefore, it is important to salient the importance of a specialist to accurately identify this kind of discourse coherence relations.

Figure 34. Interpretation relation in Portuguese.

Figure 35. Interpretation relation in Italian.

3.4.12 JOINT

The joint multinuclear relation holds between two segments that reflect different topics (Marcu Reference Marcu2000). This relation establishes a type of relationship between the nucleus and satellite, in which the nucleus provides different information that are not of the same type. Hence, they are not in an identifiable semantic or pragmatic relation, nor do they form an enumeration (Stede et al. Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017). Furthermore, it is also used when a multinuclear relation is needed (from the text to global perspective). However, it is no specific relations are applicable. Lastly, the nucleus adds information that is not comparable and is not in temporal sequence. For instance, observe the following sentence: “I bought a boot, a sneaker, and a slipper”. The terms “boot,” “sneaker,” and “slipper” are semantically compatible, but it is not an example of the JOINT relation. Differently, in the following sentence: “The talented young plays the piano and constantly enjoys traveling to Asia”, the information is distinct and not comparable; hence this is considered an example of the j oint relation. The typical connectives for the joint relation are additive connectives (Stede et al. Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017). Table 12 describes the definitions for the joint relation. Notice it provides semantic information and presents at least two nuclei. Although there are not any constraints on the nuclei, the reader recognizes that the nucleus holds between two segments that denote different things. Figures 36, 37, and 38 show examples of the JOINT discourse coherence relation. Observe that the nuclei present a segment of information that while it is related denotes different aspects. Furthermore, the additive connective “and” is a discourse marker to identify the joint relation. Nevertheless, it is necessary to evaluate first whether it would be classified as SEQUENCE discourse coherence relation (see Section 3.4.20). Other examples of additive connectives are “in addition”, “additionally”, and “also”.

Table 12. Joint relation constraints

Figure 36. Joint relation in Spanish.

Figure 37. Joint relation in Portuguese.

Figure 38. Joint relation in Italian.

Table 13. Justify relation constraints

Figure 39. Justify relation in Spanish.

3.4.13 JUSTIFY

The “justifications” consist of linguistic structures with argumentation functions. As claimed by Ducrot et al. (Reference Ducrot, Bruxelles and Bourcier1980) and Ducrot (Reference Ducrot1987), the justification phenomenon presents two main elements: argumentation conjunctions and argumentation indicators. Tseronis (Reference Tseronis2011) explains that augmentation conjunctions comprise a function of connecting two or more propositions, while argumentation indicators are expressions or words like “only” and “almost,” which change the argumentation potential within the boundaries of a proposition and connect a sentence to another sentence. In RST, the justify relation provides to the reader’s comprehension of the satellite increases the reader’s readiness to accept the writer’s right to the effect (Mann and Thompson Reference Mann and Thompson1987). Moreover, Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001) claim that the satellite acts as an argument to converse with the reader on the information presented by the writer within the nucleus. Also, the nucleus presents a subjective statement or thesis or claim, which the reader might not accept or might not regard as sufficiently important or positive, besides the satellite provides a statement of a fundamental (e.g., political, moral) attitude of the acting person (Stede et al. Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017). Lastly, the typical connectives are explanatory coordinate conjunctions. Table 13 describes the definitions for the justify relation. Note that there are not any constraints on the nucleus and satellite. In addition, the constraints on the nucleus and satellite consist of the understanding that the satellite will make it easier for readers to accept the nucleus or to share the particular viewpoint of the writer. Finally, the justify relation affects the reader’s readiness to better accept the writer’s information presented in the nucleus. Figures 39, 40, and 41 show examples of the justify relation. Observe that the nucleus presents a fact related to the writer, which is justified by information provided in the satellite. Therefore, to identify this relation, the nucleus must present a proposition, which is justified by the proposition presented in satellite.

Figure 40. Justify relation in Portuguese.

Figure 41. Justify relation in Italian.

3.4.14 MOTIVATION

Mann and Thompson (Reference Mann and Thompson1987) claim that the motivation relation is commonly found in texts evoking an action on the part of the reader, although advertising text typically largely consists of motivating material. According to Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017), it establishes a relationship between the nucleus and satellite, in which the nucleus should present an action to be performed by the reader, and the satellite presents a reason for performing the action described in the nucleus. Moreover, typical connectives used in the motivation relation are causal connectives. Finally, the motivation increases the reader’s desire to perform the action, in contrast with the enablement that informs the reader how to do it. These two relations are often found together, their satellites linked to a common nucleus (Potter Reference Potter2018). In a summarized way, this relation relates to any utterance that expresses the speaker’s desire that the hearer performs some action (the nucleus) which material will justify the requested action (the satellites). Table 14 describes the definitions for the motivation relation. Notice it presents only one nucleus (mononuclear) and provides pragmatic (intentional) information. It includes constraints on the nucleus, which must present an action unrealized. Moreover, there are not any constraints on the satellite. Also, in the motivationrelation, the nucleus must present an action in which the reader is the actor (including accepting an offer), unrealized concerning the context of the nucleus (Mann and Thompson Reference Mann and Thompson1987). Figures 42, 43, and 44 show examples of the motivation relation. Observe that the nucleus provides an action to be performed and, in the satellite, some information that fruitfully motivates the reader to perform that action. Lastly, as is well-known from the previous discussion, each RST relation holds different effects on the reader. Therephore, there is a desire of the reader to act on the nucleus. Accordingly, the motivation relation may only be used when the reader is encouraged to perform a certain activity (nucleus), on the grounds of the satellite (Stede et al. Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017).

Table 14. Motivation relation constraints

Figure 42. Motivation relation in Spanish.

Figure 43. Motivation relation in Portuguese.

Figure 44. Motivation relation in Italian.

3.4.15 NON-VOLITIONAL CAUSE

More broadly, the definition for “volition,” taking into consideration linguistic studies, is related to the intentional or unintentional nature of a subject or agent to act. According to the typology of modalities, and later revisited and expanded according to discursive-functional grammar (FDG) (Hengeveld et al., Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008), the volitional modality, as it is denominated by authors, the volitional concept, is understood, concerning the domain semantic, as a type of modularization relating to what is (un)desirable, being situated, hence, on the axis of volition, and presenting three types of modal orientation: participant, event, and proposition (Hengeveld Reference Hengeveld2004). In RST, the non-volitional cause relation is defined as a type of relationship between the nucleus and satellite of which the nucleus comprises a volitional action unrealized, and on the satellite, there are no constraints (Mann and Thompson Reference Mann and Thompson1987). Table 15 describes the definitions in terms of constraints on the nucleus and satellite, as well as the combination of both for the non-volitional cause relation. Notice it presents only a nucleus and semantic information. Besides that, the nucleus must hold at least one non-volitional action. Otherwise, there are no constraints on the satellite. As previously stated, the RST relations carry an effect on the reader. Therefore, in this relation, the reader recognizes the satellite’s direct cause of the nucleus. Figures 45, 46, and 47 show examples of the non-volitional cause relation. Observe that the satellite comprises a situation that, by means, other than motivating a volitional action, caused the situation presented in the nucleus, without the presence of the satellite (Mann and Thompson Reference Mann and Thompson1987). Finally, the nucleus is caused by the non-volitional fact provided in the satellite.

Table 15. Non-volitional cause relation constraints

Figure 45. Non-volitional cause relation in Spanish.

Figure 46. Non-volitional cause relation in Portuguese.

Figure 47. Non-volitional cause relation in Italian.

Table 16. Non-volitional result relation constraints

Figure 48. Non-volitional result relation in Spanish.

3.4.16 NON-VOLITIONAL RESULT

The point of departure to understand the non-volitional result relation consists of the fact that it presents the same set of proprieties from non-volitional cause, except for the fact that the position of the nucleus and satellite is inversely proportional. As discussed previously, the definition of “volition” refers to the intentional or unintentional nature of a subject or agent to act. In RST, the non-volitional result relation is defined as a type of relationship between the nucleus and satellite, in which the satellite comprises necessarily a non-volitional action, even though there are no constraints on the nucleus (Mann and Thompson Reference Mann and Thompson1987). Once again, the relationship between the nucleus and satellite is inversely proportional to the non-volitional cause. Table 16 describes the definitions for the non-volitional result relation. Notice it is mononuclear and provides semantic information. Furthermore, there are no constraints on the nucleus; however, the satellite must supply a non-volitional action. Lastly, in the non-volitional result relation, the reader recognizes that the nucleus may have caused the information provided in the satellite. Figures 48, 49, and 50 show examples of this relation. Observe that the nucleus comprises information more relevant than the situation presented in the satellite. In addition, the nucleus provides relevant information to understand the context, and the information presented in the nucleus is caused by the situation provided in the satellite.

Figure 49. Non-volitional result relation in Portuguese.

Figure 50. Non-volitional result relation in Italian.

Table 17. Otherwise relation constraints

3.4.17 OTHERWISE

In RST, the otherwise relation is defined as a type of mutually exclusive relation between two elements of equal importance, in which the situations presented by both the satellite and the nucleus are unrealized (Carlson and Marcu, Reference Carlson and Marcu2001). In addition, the realization of the situation associated with the nucleus will prevent the realization of the consequences associated with the satellite. In the same settings, Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) argue that the this relation comprises a type of relationship between the nucleus and satellite, in which the nucleus presents a hypothetical, future, or in other words, unreal situation, and the satellite presents a hypothetical, future, or in other ways unreal situation. Finally, the realization of the nucleus impedes the realization of the satellite (Mann and Thompson Reference Mann and Thompson1987). Table 17 describes the definitions for the otherwise relation. Notice it is mononuclear and provides semantic information. Furthermore, the satellite, as well as the nucleus, must hold an unrealized situation, and the reader recognizes the dependency relation of prevention between the realization of the nucleus and the realization of the satellite (Stede et al., Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017). Figure 51, 52, and 53 show examples. Observe that the nucleus provides a hypothetical or future situation. Likewise, the satellite also provides a hypothetical or future situation. Accordingly, in the otherwise relation, the nucleus and satellite should accommodate an unrealized situation.

3.4.18 PURPOSE

Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001) claim that in the purpose relation, the situation presented in the satellite is only putative; that is, it is yet to be achieved. Furthermore, this relation may be paraphrased as “nucleus to satellite.” In the same settings, Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) define thepurpose relation as a causal relationship in a wide sense. In other words, the difference between the relations volitional and non-volitional cause and result is that within the purpose relation, the satellite is signaled as hypothetical/unrealized and represents the intention or goal of the acting person. The typical connective in purpose relation is “to”. In a summarized way, this relation expresses purpose, objective, or end, and it is typically introduced by the final adverbial subordinate conjunctions (e.g., to, that, in order to); hence clauses classified as final adverbial subordinate may be candidates for this relations (e.g. “it is necessary for us to fight so that we can triumph.”). Table 18 describes the definitions in terms of constraints on the nucleus, satellite, and the combination of both for the purpose relation. Notice it presents only a nucleus and semantic information. Moreover, the nucleus comprises an action, and the satellite provides a situation that is unrealized. Regarding the effect on the reader, the piece of information provided in the nucleus is recognized as a starting activity to realize the satellite. Figures 54, 55, and 56 show examples. Observe that the nucleus supplies an activity or action, and in the satellite, a hypothetical or unrealized situation is presented. In addition, on the report of Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001) in this relation, the particle “to” to indicate the infinitive verbs must not be confused with a post-nominal modifier.

Figure 51. Otherwise relation in Spanish.

Figure 52. Otherwise relation in Portuguese.

Figure 53. Otherwise relation in Italian.

Table 18. Purpose relation constraints

Figure 54. Purpose relation in Spanish.

Figure 55. Purpose relation in Portuguese.

Figure 56. Purpose relation in Italian.

3.4.19 RESTATEMENT

Mann and Thompson (Reference Mann and Thompson1987) define the restatement as a type of relation that establishes a relationship between the nucleus and satellite, in which the satellite restates the nucleus, where the satellite and the nucleus are of comparable bulk. Furthermore, Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001) claim that it is always mononuclear, where the satellite and nucleus are of (roughly) comparable size. Besides, the satellite reiterates the information presented in the nucleus, typically with slightly different wording; nevertheless, it does not add to or interpret the information. In the same settings, Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) suggest that it provides a nucleus that precedes the satellite in the text, and the satellite repeats the information given in the nucleus using different wording. Hence, the nucleus and satellite are of roughly equal size, and the reader recognizes the satellite as a restatement of the nucleus. The typical connective is in “other words”. Lastly, the restatement establishes a relationship between the nucleus and the satellite, in which the satellite presents a reformation of the information from the nucleus, therephore, paraphrasesFootnote e are candidates for the restatement relation. Table 19 describes the definitions for the restatement relation. Notice it is a mononuclear relation and provides semantic information. Furthermore, according to Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017), the nucleus precedes the satellite in the text, and the satellite repeats the information given in the nucleus using different wording. Also, there are not constraints on the nucleus and satellite, and the nucleus and satellite are of roughly equal size. Figures 57, 58, and 59 show examples of this relation. Observe that the nucleus presents information, which was reformulated by a piece of information given by the satellite.

Table 19. Restatement relation constraints

Figure 57. Restatement relation in Spanish.

Figure 58. Restatement relation in Portuguese.

Figure 59. Restatement relation in Italian.

Table 20. Sequence relation constraints

3.4.20 SEQUENCE

The sequence relation comprises information sequentially chained. Nevertheless, temporal succession is not the only type of succession for which this relation might be appropriate. Others could include descriptions of a group of cars according to size or cost, colors of the rainbow, who lives in a row of apartments, etc. (Mann and Thompson Reference Mann and Thompson1987). Moreover, Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001) define it as a type of relation multinuclear that establishes a relationship between nuclei in which a list of events is presented according to chronological order or inverted chronological order. In the same settings, Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) suggest that it consists of a relationship between two or various nuclei, in which the nuclei describe states of affairs that occur in a particular temporal order, and the reader recognizes the succession relationships among the nuclei. The typical connectives are “then”, “before”, and “afterward”. Table 20 describes the definitions for the sequence relation. Notice that the relevant property of this relation consists of the fact that the nuclei comprise situations in a temporal sequence. In addition, the main difference between the sequence relation and other multinuclear relations such as the joint is the secession temporal relationships among nuclei. Figures 60, 61, and 62 show examples of this relation. Observe that the information presented in the nuclei provides a type of semantic information in sequence. Hence, the reader must recognize the presence of a temporal sequence among the nucleus.

Figure 60. Sequence relation in Spanish.

Figure 61. Sequence relation in Portuguese.

Figure 62. Sequence relation in Italian.

3.4.21 SOLUTIONHOOD

The solutionhood relation establishes a relationship between the nucleus and satellite, in which the reader recognizes that the body of the text presents a solution to the problem of having to clean floppy disk heads too often (Stede et al. Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017). Furthermore, the terms “problem” and “solution” are broader than one might expect. In Carlson and Marcu (Reference Carlson and Marcu2001), the authors titled problem-solution this relation. Shortly, in order to identiy this relation, one textual span must comprise a problem, and the other text span must comprise a solution. In addiation, it should be pointed out that this relation can be mononuclear or multinuclear, depending on the context. When the problem is perceived as more important than the solution, the problem is assigned the role of the nucleus, and the solution is the satellite. In that case, the relation would be monocluear. Otherwise, it would be multinuclear. Also, Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) claim that the nucleus precedes the satellite in the text, and the reader recognizes the nucleus as a solution to the problem presented in the satellite. Lastly, this relation rarely is signaled by connectives (Stede et al. Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017). Table 21 describes the definitions for the solutionhood relation. Note that the content of the satellite may be regarded as a problem. Otherwise, the nucleus presents a solution to the problem presented in the satellite. Moreover, the reader must recognize the nucleus as a solution to the problem presented in the satellite. Figures 63, 64, and 65 show examples of this relation. Observe that the nucleus and satellites do not present any discourse marker or connective. In addition, the satellite explicitly provides a solution proposal for the event presented in the nucleus.

Table 21. Solutionhood relation constraints

Figure 63. Solutionhood relation in Spanish.

Figure 64. Solutionhood relation in Portuguese.

Figure 65. Solutionhood relation in Italian.

3.4.22 SUMMARY

Here, a relevant point of departure consists of the fact that the size of the summary presented in the satellite is shorter than the size of the nucleus. Therefore, in the summary relation, the satellite summarizes the information presented in the nucleus, and the emphasis is on the situation presented in the nucleus. According to Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017), it is defined as mononuclear that establishes a type of relationship between the nucleus and satellite, in which the satellite succeeds the nucleus in the text and repeats the information given in the nucleus, however, in a shorter form. Furthermore, the typical connectives are “short”, “shortly”, and “in a summarized way”. Table 22 describes the definitions for the summary relation. Note that the nucleus presents more than one EDU. Although there are no constraints on the satellite, the nucleus position is succeeded by the satellite position. Lastly, the satellites present the same information presented in the nucleus, however, shortly. Figures 66, 67, and 68 show examples of this relation. Observe that it establishes a relationship between the nucleus and the satellite, in which the satellite presents a restatement of the content of the nucleus, which is shorter in the bulk. Hence, the satellite summarizes the information presented in the nucleus.

Table 22. Summary relation constraints

Figure 66. Summary relation in Spanish.

Figure 67. Summary relation in Portuguese.

Figure 68. Summary relation in Italian.

Table 23. Volitional cause relation constraints

Figure 69. Volitional cause relation in Spanish.

Figure 70. Volitional cause relation in Portuguese.

3.4.23 VOLITIONAL CAUSE

According to Mann and Thompson (Reference Mann and Thompson1987), the volitional cause relation is defined as a type of relationship between the nucleus and satellite in which the nucleus provides the cause of the volitionalFootnote f action presented in the satellite. In the same settings, Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017) claim that the nucleus and satellite must provide a state or event in the world. In order words, the state/event in the nucleus must be caused by the state/event in the satellite, and the reader must recognize the satellite as a cause of the content provided in the nucleus. Furthermore, the volitional cause relation is frequently confused with the motivation relation (see Section 3.4.14). Nonetheless, the main element that distinguishes them consists of the intended effect of the motivation relation to make the reader want to perform an action evoked in the text. In Table 23, we describe the definitions in terms of constraints on the nucleus and satellite along with the combination of both for the volitional cause relation. Notice it is a mononuclear relation and provides semantic information. Moreover, it is defined as a type of relationship between the nucleus and satellites without any constraints on the satellite, while the nucleus must provide information on a volitional action. Besides, there are constraints on the nucleus and satellite together. Finally, the typical connectives are “because”, “since”, and “therefore”. Figures 69, 70, and 71 show examples of the volitional cause relation. Observe that the nucleus presents necessarily a volitional information. As it is known from previous discussions, the conception of “volition” according to linguistics studies is related to the intentional or unintentional nature of a subject or agent to act.

3.4.24 VOLITIONAL RESULT

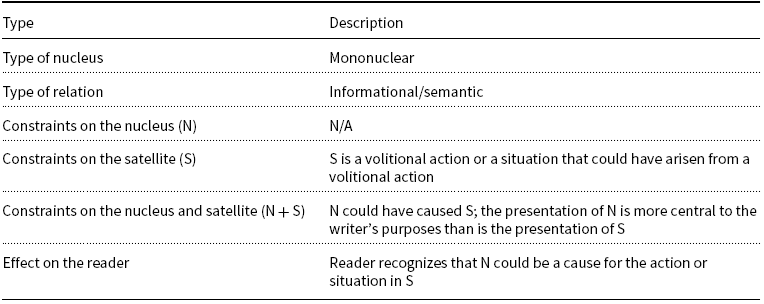

According to Mann and Thompson (Reference Mann and Thompson1987) the volitional result relation comprises a volitional action or situation that may appear from a volitional action. In Stede et al. (Reference Stede, Taboada and Das2017), the volitional result relation is titled “result” relation. In the same settings, they define this relation as type of relationship between nucleus and satellite, in which the information presented in the satellite is the cause of the situation presented in the nucleus. Furthermore, the result, which is the nucleus, is the most important part of this relation. Therefore, without accessing the satellite, the reader may not know what caused the result in the nucleus. Lastly, the typical connectives are “because”, “since”, and “therefore”. Table 24 describes the definitions in terms of constraints on the nucleus and satellite and the combination of both. Notice it is a mononuclear relation that comprises semantic information and the relationship between the nucleus and satellite. In this relation, the very important point that we should keep in mind consists of the fact that the constraints on the nucleus and satellite present information that are inversely proportional to the volitional cause relation. Furthermore, in this relation, there are no contractions on the nucleus, and the satellite provides a volitional action. Whether it is compared with the volitional cause, the nucleus provides a volitional action, and no contractions are on the satellite. Additionally, in the volitional result, the reader recognizes that the nucleus probably has caused the action supply in the satellite. Figures 72, 73, and 74 show examples of the volitional result relation. Observe that the satellite comprises necessarily the presence of volitional information, and the nucleus provides the result of volitional action presented by satellite.

Figure 71. Volitional cause relation in Italian.

Table 24. Volitional result relation constraints

Figure 72. Volitional result relation in Spanish.

Figure 73. Volitional result in Portuguese.

Figure 74. Volitional result in Italian.

4. Annotation bias

Annotation bias or annotator bias consists of differences between annotator preferences for subjective reasons (Amidei, Piwek, and Willis Reference Amidei, Piwek and Willis2020). According to Sampson and Babarczy (Reference Sampson and Babarczy2008) and Amidei et al. (Reference Amidei, Piwek and Willis2018), annotators most diverge in language annotation tasks due to a range of ineliminable factors such as background knowledge, preconceptions about language, geographic factors (origin) and general educational level. In this survey, we aim to provide a well-defined, structured and accurate discourse annotation guideline focused on LRLs, which is easy to follow and rich in examples of discourse coherence relations, as a strategy to mitigate potential annotator bias. We also recommend two strategies to mitigate bias: (i) selection of expert annotators and (ii) diverse profile of annotators (gender, race, political orientation, etc.).

5. Evaluation of RST trees

Evaluation metrics of discourse coherence are important to distinguish coherent texts from incoherent texts. The evaluation of RST trees has focused on (i) human-based evaluation, which uses expert human raters, and (ii) automatic-based evaluation, which uses classical and neural machine learning (ML) algorithms. Guz et al. (Reference Guz, Bateni, Muglich and Carenini2020) propose to evaluated the RST tree using neural networks leveraging its representations as features to evaluate coherent texts. Wan et al. (Reference Wan, Kutschbach, Lüdeling and Stede2019) compared automatically RST trees. Naismith et al. (Reference Naismith, Mulcaire and Burstein2023) produced ratings by training GPT-4 contrasting with expert human raters to assess discourse coherence.

6. Main challenges and opportunities

While the RST has been applied to a wide variety of successful applications, we should not simply see it without any criticism. For instance, discourse coherence relations may present a relevant level of ambiguity. In addition, the discourse segmentation process was not accurately defined by RST’s authors. Hence, the identification automatic of an EDU is a complex task. Nevertheless, discourse-aware computational resources have proved to be useful and efficient in different NLP applications. Lei et al. (Reference Lei, Huang, Wang and Beauchamp2022) showed that embedded discourse structure for sentence-level media bias effectively increases the recall by 8.27 percent–8.62 percent and precision by 2.82 percent–3.48 percent. Devatine et al. (Reference Devatine, Muller and Braud2022) predicted the political orientation (left, center, right) of news articles using a discourse framework. Aldogan and Yaslan (Reference Aldogan and Yaslan2015) and Appel et al. (Reference Appel, Chiclana, Carter and Fujita2016) evaluated different features including discourse structures for sentiment analysis. Alós (Reference Alós2015) used discourse structure for automatic translation. Huang (Reference Huang2013) applied RST to building clinical question-answering systems. Hewett (Reference Hewett2023) applied RST for the text simplification task, and Vargas et al. (Reference Vargas, Benevenuto and Pardo2021) used RST for multilingual fake news detection. Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Gan, Cheng and Liu2020) proposed a discourse-aware neural summarization model, which extracts sub-sentential discourse units (instead of sentences) as candidates based on RST trees and coreference mentions. And, Li et al. (Reference Li, Wu and Li2020) showed that an EDU is a more appropriate textual unit of content selection than the sentence unit for abstractive summarization. RST is also used for natural language generation (Mann Reference Mann1984; Hovy Reference Hovy1990; Isard Reference Isard2016; Adewoyin, Dutta, and He Reference Adewoyin, Dutta and He2022) and for building of discourse parsing (Li, Li, and Hovy Reference Li, Li and Hovy2014; Mabona et al. Reference Mabona, Rimell, Clark and Vlachos2019).

7. Final remarks

We provide the first discourse annotation guideline using the RST for LRLs. Specifically, we accurately described 24 (twenty-four) discourse coherence relations in three romance languages: Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish. We also present a comprehensive survey addressing discourse analysis in AI, hence offering an accessible resource to new researchers and annotators. Finally, we hope to contribute to the advancement of research and NLP systems development focused on discourse-level language understating and generation for LRLs.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Marcello Gecchele for providing reliable and expert RST-annotated examples in Italian.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.