Introduction

At the beginning of 2014, Ukraine experienced a series of turbulent events with no precedence in the contemporary history of the state. On 21 February 2014, the notorious Euromaidan protest reached its violent culmination. The following day, President Viktor Yanukovych and his close allies escaped from the country. Immediately after that, Russia launched a de facto campaign of aggression against Ukraine: the Crimean Peninsula was annexed, and in the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, self-proclaimed “people’s republics” emerged, also enjoying Russia’s political and material support. These events led to an armed conflict which affected a significant part of Ukraine’s population.

As a result of these developments, the Ukrainian state faced the peace-versus-justice dilemma. On the one hand, there is an obvious need to address the legacy of violence generated by conflict; on the other hand, there is an overwhelming expectation on the side of society to seek peaceful resolution. Despite the passage of five years since the beginning of the Donbas conflict, the Ukrainian authorities have not elaborated a comprehensive approach that could point to prospective means of resolving this dilemma. At the same time, the Ukrainian state addresses conflict-related wrongdoings based on provisions of the criminal code that existed before the outbreak of the conflict. Without any doubt, this practice generates consequences that may have an impact on dynamics of reconciliation between parts of the divided society: persons engaged in warfare face the risk of punishment, and those punished are branded as criminals. The very awareness of these kind of consequences may serve as a disincentive for government opponents to engage in constructive peacebuilding talks.

This article is aimed at analysing this provision of punishment by Ukrainian courts for crimes related to the Donbas conflict. Our main research question is whether Ukrainian courts took into account the specific circumstances that arose with the outbreak of the Donbas conflict when issuing sentences to those who engaged themselves in the conflict. In other words, is there any evidence of a deliberate policy of mitigating punishments to those who engaged themselves in different sorts of anti-government actions associated with the Donbas conflict, for the sake of achieving peace? This leads to our secondary question: what are the impacts of Ukrainian court practices on the process of national reconciliation?

The article starts with a section devoted to explaining how provision of justice is used to address the legacy of armed conflict, with special attention paid to sources of the peace-versus-justice dilemma. In the second section, the peculiarities of the Donbas conflict are examined, in order to understand the specific nature of the peace-versus-justice dilemma faced by the Ukrainian authorities. The section also presents an overview of the relevant steps taken by Ukrainian authorities to provide justice. The third section explains our approach to data collection, which allowed us to analyze relevant court decisions and specific aspects of these decisions providing useful evidence. Section four contains a comparative analysis of relevant court decisions, with the fundamental aim of indicating the conditions that can be regarded as necessary and sufficient for issuing less punitive judgements. Our findings are then discussed and final conclusions are formulated.

The Significance and Peculiarities of Justice in Conflict-Affected Societies

Armed conflicts are inevitably associated with violence, which tends to generate lasting resentments, and through them, a lasting impact on the politics of affected societies, going far beyond the time scope of the conflict itself (Maddison Reference Maddison2017, 21–39). At the same time, such conflicts should be regarded as extraordinary circumstances, in which societies are forced to operate outside of their established institutional infrastructure. From this perspective, despite their fundamentally destructive essence, armed conflicts can also be seen as “originary and transgressive moments of symbolic and legal innovation and for constitutional creation” (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2008, 292).

Managing a conflict and the post-conflict situation in a way that reduces the negative impacts of violence and clears the way for constructive politics is by no means an easy task. Extensive literature has been devoted to this issue, the review of which would go beyond the thematic scope of this article. What should be stressed is that provision of justice is usually regarded as a necessary condition for establishing long-lasting, positive peace (Galtung Reference Galtung1969).

However, the mutual relationship between provision of justice and establishing peace is far from straightforward. In fact, these two ideas can be regarded as contradictory. As was clearly explained by Manas (Reference Manas1996), “the pursuit of justice entails the prolongation of hostilities, whereas the pursuit of peace requires resigning oneself to some injustices”. (43) This is the essence of the so-called “peace-versus-justice” dilemma, which is inevitably associated with any attempt to find a constructive way out of conflict situations (Sriram and Pillay Reference Sriram and Pillay2010).

In order to approach the uneasy relationship between peace and justice in a systematic way, we will draw on achievements from the interdisciplinary academic field of transitional justice (TJ). Although the concept emerged from studying the experience of transitions between political regimes, it was soon adapted as an instrument for analysing justice-related aspects of post-conflict situations. According to Kofi Annan’s 2004 report, the concept refers to “a full range of processes and mechanisms associated with a society’s attempts to come to terms with a legacy of large-scale past abuses, in order to ensure accountability, serve justice and achieve reconciliation. These may include both judicial and non-judicial mechanisms, with differing levels of international involvement (and none at all) and individual prosecutions, reparations, truth seeking, institutional reform, vetting and dismissals, or a combination thereof” (United Nations 2004). It should be stressed that—as in the case of peace-making—TJ literature is vast. We will deliberatively leave further theoretical debate on the essence and boundaries of TJ aside, and use the above-mentioned definition, because it can be regarded as a sort of vade mecum of both theoretical knowledge and lessons learned from practice.

Generally, the concept of TJ refers not to a specific type of justice, understood as a philosophical notion, but to a specific procedure for the provision of justice in situations when resting upon existing rules is impossible or undesirable. The transitional element of the concept refers to the extraordinary circumstances mentioned above, when, due to some sort of crisis, a society undergoes a fundamental shift (in the context of this article, a transition from war to peace).

TJ literature draws attention to two essential features of such a procedure for the provision of justice. First, TJ is normatively driven (Gready and Robins Reference Gready and Robins2014). In other words, policies fitting into the category of TJ should strive to strengthen a certain set of values. Considering that the concept of TJ was developed in the context of what Huntington (Reference Huntington1991) called a “third wave of democratization,” it was associated with values constituting the foundations of the widely understood western political order. Therefore, the rule of law and human rights, framed mostly by international law and its practical application—the case-law of international courts and tribunals—come foremost. Clearly, when applied in the context of transition from war to peace, TJ is expected, above all, to contribute to reconciliation, which is a prerequisite for building a liberal political order. Reconciliation is, in turn, understood not as some sort of idealized state of affairs in which all antagonisms are eliminated, but as a dynamic process of transferring a conflict into the political field, “a mode of political engagement and agonistic struggle” that tries to strike a balance between short-term stability and long-term aspirations (Maddison Reference Maddison2017, 13).

The second, and probably most important feature of TJ, is that it inevitably contains what can be termed a “quantum of politics.” To a certain degree, this depends on the interplay of interests among the actors involved: wrongdoers want to avoid prosecution, victims want to obtain compensation (not necessarily material), and political parties want to utilize TJ policies in order to increase their share of the electorate (Elster Reference Elster2004, 84–89). To put it in another way, whenever we deal with the above-mentioned extraordinary circumstances, the problem of a growing gap between legal codes and community sentiments manifests itself. People generally perceive how strongly the offenders deserve punishment based on their beliefs about how wrongfully the offenders have behaved (Darley and Alter Reference Darley and Alter2013, 184–85). When the community faces new, previously unexperienced types of wrongdoings (such as the sort committed during armed conflict), perceptions of the wrongfulness of such deeds and deservingness of punishment are likely to rise; at the same time, the adequacy of relevant legal codes is not guaranteed, as they are designed for much more predictable “ordinary” circumstances. Furthermore, those accused of wrongdoing by an interested state may argue that their cause is actually just (Armitage Reference Armitage2017, 132). As a result, guilt is a matter of negotiation between sides in the conflict, and the practice of punishment may not only reflect considerations of a purely legal nature (assessing guilt from the perspective of binding legal codes), but also considerations of a political nature (e.g. if our ultimate goal is to stop hostilities, it may pay to deliberately tighten or ease the approach to punishment). It should be noted, however, that nowadays international criminal law sets a clear threshold for “minimal justice”: international crimes must be punished.

Based on these brief considerations, we can conclude the following: any society that has to deal with the consequences of an armed conflict and seeks reconciliation will face the above-mentioned peace-versus-justice dilemma. Any steps taken by an interested state in this field will most probably fit into the category of TJ. However, the existing theoretical knowledge does not provide any sort of universal “recipe” for solving the dilemma, because the effectiveness of such policies will ultimately depend on the complexities and unique circumstances in which they are applied (Duthie Reference Duthie2017).

In this context, one can expect to observe two phenomena when examining conflict-affected societies. On the one hand, in order to address the peace-versus-justice dilemma, interested states are likely to make use of the existing institutional infrastructure, law enforcement agencies, and courts, in the first instance, because they possess the appropriate infrastructure for imposing sanctions on persons who break binding rules and norms (they may be called offenders, perpetrators, wrongdoers etc.). In other words, the primary response to violence generated by an armed conflict is most likely to rest upon policies of a retributive nature. This reflects the most intuitive and straight-forward understanding of “justice” in the face of wrongdoing—punishment—although provision of justice may also take the shape of restorative or purely symbolic steps of truth-seeking, as the above-mentioned UN definition of TJ clearly suggests. On the other hand, conflict-affected societies willing to transform the violent conflict into a normal political process must “negotiate” the formula for provision of justice. This may require going beyond the established “rules of the game” reflected in binding legal codes, or at least adapting them to fit the complex reality of an armed conflict.

In the following parts of the article, we will turn to analyzing the Ukrainian state’s method of dealing with wrongdoings which were committed in the context of extraordinary circumstances: the ongoing armed conflict in Donbas. Due to its recentness, the case remains largely unstudied. This provides an opportunity to explore one approach to the inevitable peace-versus-justice dilemma, and to consider its effectiveness.

The Substance of the Peace-Versus-Justice Dilemma in the Context of the Donbas Conflict and Ukraine’s Tentative Steps to Solve It

The armed conflict in the east of Ukraine started to evolve in the aftermath of probably the most remarkable event in the country’s contemporary history—the Euromaidan uprising that took place at the end of 2013—beginning of 2014. The protests ended with the escape of President Viktor Yanukovych to Russia on February 22, 2014. Almost immediately, on March 1, it was followed by rallies in the cities of Kharkiv, Odesa, Donetsk, Kherson, and Mykolaiv (all situated in the south and east of Ukraine). The participants openly expressed their disagreement with the change of authorities in Kyiv. It is important to note that the support for Euromaidan was concentrated in the western and central regions of the country (Democratic Initiatives Foundation 2014). It was therefore no surprise that the narrative presenting the protests and their outcome as an illegal coup d’état gained fertile ground in the east and in the south. A detailed analysis of these issues can be found elsewhere (Wilson Reference Wilson2014).

Rallies against the post-Euromaidan change of authorities also took place in the Crimean Peninsula. The latter were used by local pro-Russian groups, openly supported by the Russian military, to organise a referendum on the independence of Crimea on March 16, 2014. Two days later, on March 18, an agreement was signed in Moscow on the annexation of Crimea to the Russian Federation. There are all grounds to regard these events as an act of aggression against Ukraine (Grant Reference Grant2015, 26–33).

Events in Donbas generally fit the same pattern. Anti-government meetings were soon complemented with secessionist ones. There were instances of official buildings being occupied throughout the region, accompanied by the proclamation of “people’s authorities.” On May 11, 2014, these “authorities” conducted unconstitutional referendums (according to Ukraine’s constitution, issues of altering the territory of Ukraine are resolved exclusively by an all-Ukrainian referendum), which provided the dubious basis for the so-called independence of the self-proclaimed “people’s republics” of Donetsk (DNR) and Luhansk (LNR). Although Russia clearly supported the emergence of both putative states, there were no attempts to annex the secessionist territories as in the case of Crimea. It is not our goal here to provide a definite statement about the nature of the conflict—in fact, there is evidence to support both claims that the conflict is essentially an interstate armed conflict and claims that it is essentially a non-international armed conflict. What is important from the perspective of this article is that, although Russia’s policy should be regarded as a necessary condition for the outbreak of the conflict, many fellow Ukrainian citizens were, and still remain, engaged in warfare and other forms of hostilities against the Ukrainian state. This situation constitutes the primary specificity of the peace-versus-justice dilemma in the discussed case: the goal of national reconciliation has generated the need to come to terms with the scope of responsibility and guilt of those who supported separatist ideas and/or somehow participated in warfare, and solving this problem requires what was referred to above as going beyond the established “rules of the game.”

Unlike the case of Crimea, the Ukrainian government decided to use force against the secessionists in Donbas. On April 13, 2014, the counter-terrorist operation (ATO) was authorised to oppose the growing centrifugal tendencies. By the summer of 2014, the crisis had escalated to a full-fledged armed conflict. On September 5, 2014, the first ceasefire agreement was signed in Minsk by representatives of the Organisation of Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), Ukraine, Russia, and leaders of the self-proclaimed “republics” of DNR and LNR (hereafter referred to as the Minsk-1 agreement). It was followed by a new wave of violence at the beginning of 2015 and the signing of a second ceasefire agreement on February 12, 2015 (hereafter referred to as the Minsk-2 agreement). After the Minsk-2 agreement, a relative degree of calm, though not a complete end to the violence, was achieved.

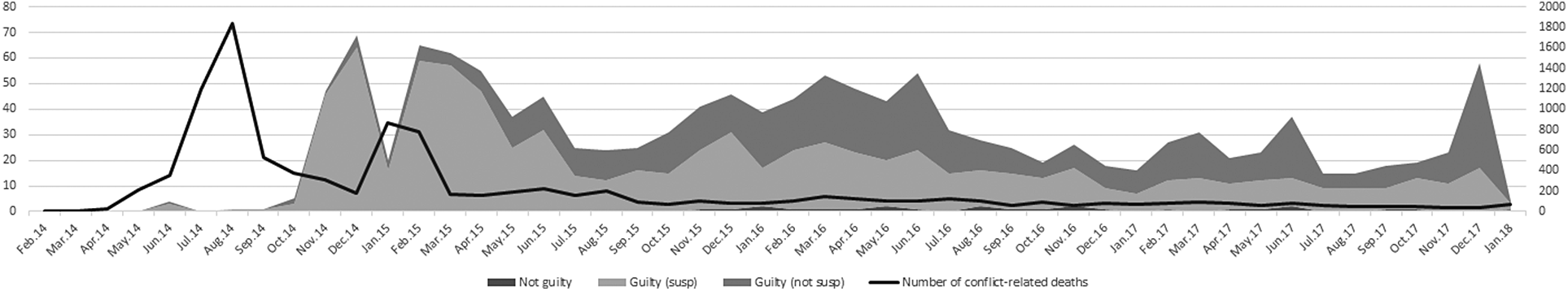

Conflict-related violence generated a number of wrongdoings, thus providing the Ukrainian state with the incentive to address them—in other words, to apply retributive justice measures. First and foremost, there were a significant number of conflict-related deaths. Figure 1 reflects the number of all conflict-related casualties and its dynamics over time. As a result of warfare, more than twenty-one thousand persons were injured (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 2016). Numerous instances of human rights violations have been reported by international organisations and NGOs, not only by militants of the “people’s republics,” but also by Ukrainian government forces (International Federation for Human Rights 2015).Footnote 1 Last but not least, for the first time since independence, Ukraine has faced the problem of internally displaced persons (IDPs), the number of which is estimated at around 1.4 million persons (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 2015). IDPs are reported to face problems regarding protection of their social rights (Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union 2017).

Figure 1. Number of Deaths Related to the Donbas Conflict.

Source: Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union’s “Memory Map” project. Note: the figure presents data on cases where the date of death is known. The “Memory Map” project has collected information on at least 1,103 more cases of conflict-related casualties where the exact date of death could not be established.

On the other hand, there are obvious incentives for Ukrainian authorities to pursue peace, even at the cost of justice. In particular, the available data on public opinion suggest that Ukrainians are largely against any sort of “hawkish” approach to resolving the conflict, and are ready to make at least some compromises with their adversaries for the sake of peace (see Figure 2). This attitude is far from being homogenous, however: the farther respondents are from the conflict area, the more reluctant they tend to be to accept compromises that might end the conflict. For those living in the direct vicinity of the self-proclaimed “republics”—and thus those who have most likely witnessed or experienced the warfare personally—the undisputable priority is the end of warfare at all possible costs (Democratic Initiatives Foundation 2019). It should be noted that there are no reliable data of the same kind reflecting the attitudes of Ukrainians living in the territories controlled by the “people’s republics.”

Figure 2. Readiness of Ukrainians to Accept Compromises with Russia and DNR/LNR.

Source: Democratic Initiatives Foundation.

At the time of writing, the Donbas conflict remains unresolved, and there is little sign of a solution being found in the foreseeable future. In such circumstances, it is not surprising that Ukrainian authorities have not developed a comprehensive TJ strategy, which would encompass at least a concept of a viable solution to the peace-versus-justice dilemma.Footnote 2

At the same time, several tentative steps regarding the provision of justice, in its most narrow sense, have been made. First, the signing of the Minsk-1 agreement was followed by the provision of amnesty for anti-government fighters who had not committed serious crimes (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine 2014). This provision remained ineffective, however, because it was subject to the condition of prior local elections being conducted in accordance with Ukrainian legislation; this condition was never fulfilled.

Second, not being a member of the Rome Treaty, Ukraine accepted the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (ICC) over alleged war crimes on the territory of Ukraine starting from February 20, 2014 (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine 2015). While the government presented this decision as a step forward in the fight against impunity, it is too early to speak about its empirical effects: at the moment of writing, the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor is continuing preliminary investigation of the situation in Ukraine. This issue is discussed in detail elsewhere (Lyubashenko Reference Lyubashenko2018).

Third, the Ukrainian state, in the face of law enforcement authorities and the judiciary, engaged in bringing to account persons who committed conflict-related wrongdoings. It is precisely in this domain that state policy has generated real consequences for individuals somehow engaged in the conflict. In the following sections of the article, we focus on this particular dimension of Ukraine’s approach to the provision of justice in the context of the ongoing Donbas conflict. It is important because, at least to a certain extent, the steps already taken may determine the development of a more comprehensive model of post-conflict TJ in the future. Relevant policies constitute a set of fait accompli, narrowing down the number of combinations of tools and approaches which could potentially form a comprehensive attempt to solve the peace-versus-justice dilemma. If a consistent method of prosecution for a certain category of deeds is established, it may be hard to find convincing arguments to withdraw from it in the future, even when reasons of a political nature exist. The same would apply in a situation where a certain group of persons was treated in a relatively lenient manner. According to Freeman (Reference Freeman2009), there may even be a practice of so-called de facto amnesties. In this case, withdrawal of changes may appear harmful to the peace process.

These considerations lead us to the following question: is there any evidence of Ukrainian courts going beyond the existing “rules of the game” and taking into account the specific circumstances that arose with the outbreak of the Donbas conflict when issuing sentences to those who engaged in the conflict? More specifically, in the following parts of the article, we aim to explore whether there is any evidence suggesting that the scope of punishment was somehow dictated by the specific circumstances of the ongoing conflict, and, therefore, whether the goal of justice was somehow given up for the sake of achieving the goal of peace.

Looking for Evidence in Ukrainian Court Decisions on Crimes Committed in the Context of the Donbas Conflict

Ukraine maintains a publicly available online register of decisions issued by its courts.Footnote 3 Importantly, the documents available in the register contain information not only about the final decision of the court, but also about some circumstances in which the acts under scrutiny were conducted. Therefore, the register constitutes a valuable source of data that can be used to analyze different aspects of wrongdoings committed in the context of the Donbas conflict (Kudelia Reference Kudelia2019), as well as the state’s approach to these wrongdoings.

In order to answer the empirical questions identified above, we collected and coded court decisions issued between April 13, 2014, the beginning date of ATO, and January 18, 2018, the date of adoption of the law which created the formal basis to reformat the ATO into the so-called Joint Forces Operation (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine 2018). Unfortunately, the register does not permit automated searches for cases related to a specific event (such as the discussed armed conflict). Therefore, identification of all relevant cases is virtually impossible: it can only be done manually, by examining all the available documents and individually assessing their relevance in connection with the Donbas conflict. The register contains more than three hundred and sixty thousand decisions on criminal cases issued during the mentioned period of time. As a result, cases referring to wrongdoings that can be committed not only in the context of the conflict, but also in ordinary peaceful circumstances (such as murders, tortures, rapes, and crimes committed by the military in peaceful times, such as desertion, etc.) were omitted and may become the object of further analysis in the future.

The collection of data was thus limited to those provisions of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (CCU), which could be utilized to address two problems. The first is the support for separatism as a political idea—it should be noted that Ukraine’s penal system is based on the nullum crimen sine lege principle, and that the CCU does not contain a crime described as separatism. The second is the problem of active engagement of individuals in hostile anti-government activities inspired by separatist ideas. Therefore, the search for relevant cases was made among decisions issued on the basis of the following provisions of the CCU.

The first category is wrongdoings classified by the CCU as crimes against the foundations of Ukrainian national security, in particular: actions aimed at effecting a violent change or an overthrow of the constitutional order, or the seizure of state power (art. 109 of the CCU); attacks on the territorial integrity and inviolability of Ukraine (art. 110, 110-2 of the CCU); and treason (art. 111 of the CCU). These are the provisions used to address acts widely referred to as de facto separatism (e.g. public support or agitation for ideas involving some form of secession of a part of the country). Hereafter we will refer to these cases as political wrongdoings.

The second category is wrongdoings classified by the CCU as crimes against public security, in particular: a terrorist act (art. 258 of the CCU), involvement in committing a terrorist act (art. 258-1 of the CCU), public appeals to commit a terrorist act (art. 258-2 of the CCU), creation of a terrorist group or terrorist organization (art. 258-3 of the CCU), facilitating the commission of a terrorist act (art. 258-4 of the CCU), financing terrorism (art. 258-5 of the CCU), and creation of illegal paramilitary or armed units (art. 260 of the CCU). These provisions were used against persons who actively engaged in or supported anti-government warfare. Hereafter we will refer to these cases as combatants’ wrongdoings.

The documents were selected and downloaded manually (automatized manipulation of the register is forbidden) and then processed and coded by a team of researchers. First of all, the relevance of documents was assessed, based on their connection to events associated with the discussed conflict. Next, the following information was extracted from the documents classified as relevant: the time and place of issuance of the judgement, basic information about the accused, information about the indictment and cooperation of the accused with the prosecution, and information about the final decision of the court. No personal data or information allowing the identification of individuals was collected (documents published in the register are anonymized).Footnote 4 It should also be noted that the construction of the register does not allow systematic tracking of the developments of a specific case in the higher instances. Therefore, entries in the resulting database do not provide a distinction between the first and second instances; each entry reflects one case of a court’s judgement of deeds committed by one person, taking into account the documented circumstances of the case. All in all, the resulting database contained descriptions of 1615 cases, including 276 cases of political wrongdoings and 1339 cases of combatants’ wrongdoings.

To demonstrate that the above approach was effective in selecting relevant documents, a similar search was made of the court register in the four-year period preceding the outbreak of the conflict. Applying similar selection criteria, only 17 relevant court decisions were identified. This observation also highlights a growing gap between legal codes and community sentiments: since the Ukrainian judiciary lacked experience in dealing with such crimes before the outbreak of the conflict, there was no established practice for applying existing legal provisions to address real deeds.

The classification of cases into two different categories is dictated by Ukrainian legal theorists, who underline significant differences between the above-mentioned types of crimes according to the CCU. Crimes against the foundations of national security (political wrongdoings) are counted among the gravest, because they constitute a threat to the most significant, fundamental social relations, upon which rests the protection of the vital interests of individuals, society, and the state (Skulysh and Zvonariov Reference Skulysh and Zvonariov Yu2011, 78). However, definitions of these crimes in the CCU are quite general and abstract (Bantyshev and Shamara Reference Bantyshev and Shamara2011, 173), potentially providing judges with considerable freedom in applying legal provisions to interpret actions of the accused. When it comes to acts labelled as combatants’ wrongdoings, the danger arises from the fact that they violate the safety of society, which may directly affect the health and life of individual citizens (Dudorov and Khavroniuk Reference Dudorov and Khavroniuk2014, 655). These cases leave much less space for the interpretation of relevant acts by judges.

Turning to the analysis of collected data, we will start with an inquiry into the dynamics of issued decisions over time in order to identify clear trends that might direct our further analysis. These dynamics are presented in Figures 3 and 4. In addition, the total number of decisions are divided into three categories, reflecting the possible outcomes for the accused: acquittals (no punishment), suspended sentences (“less punitive” decision), and unconditional sentences (“most punitive” decision).

Figure 3. Court decisions referring to instances of Donbas conflict-related political wrongdoings.

Source: Online register of Ukrainian court decisions (data on the number of court decisions); Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union’s “Memory Map” project (data on the number of conflict-related deaths).

Figure 4. Court decisions referring to instances of Donbas conflict-related combatants’ wrongdoings.

Source: Online register of Ukrainian court decisions (data on the number of court decisions); Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, “Memory Map” project (data on the number of conflict-related deaths).

The figures differ significantly. The figure reflecting judgements of political wrongdoings (Figure 3) does not show any trends in terms of a change in the courts’ approach to the assessed cases over time. The “untidiness” of the figure may be interpreted as a lack of a pattern for dealing with such cases that might have emerged over time. In contrast, the figure reflecting judgements of combatants’ wrongdoings (Figure 4) presents a more consistent approach. There are two spikes in the total number of issued decisions. They can be interpreted as reflecting two periods of intensified warfare. There is also a downward trend in the total number of decisions over time (which once again may result from the lowering intensity of the conflict) as well as a decline in the proportion of suspended sentences (which suggests that the courts’ approach became more severe over time).

There is also one clear similarity between the figures: acquittals constitute a small minority of all issued court judgements. The main qualitative difference reflecting different levels of severity in the punishment of actions representing similar types of crimes is thus between suspended sentences and unconditional sentences. In the following part of the article, we will take a closer look at this difference.

Conditions Explaining Less Punitive Court Decisions

As mentioned in the previous section, it would be correct to say that the approach of the Ukrainian state to wrongdoers who somehow supported the idea of separatism or participated in anti-government warfare is relatively harsh: cases which end up in court tend to receive a “guilty” verdict. At the same time, there is an obvious diversification into “more” and “less” punitive verdicts in the form of suspended prison sentences. The possibility to suspend imprisonment is one area in which Ukrainian judges have a significant level of discretion (Dudorov and Khavroniuk Reference Dudorov and Khavroniuk2014, 394). In cases where the punishment does not exceed five years of imprisonment, the judge, having taken into account the circumstances of the case, has the freedom to establish a term of probation and additional obligations, under which the accused may forego imprisonment.

One should remember that Ukrainian judges have no previous experience of issuing decisions regarding the above-mentioned types of crimes, and therefore there is no established judicial practice on how to address these sorts of wrongdoings. Judges have had to “learn” how to deal with them “on the go.” This fact presumably increased the judges’ openness to arguments suggesting that, in passing a sentence, they should also pursue the goal of peace and therefore use their discretion to diversify the severity of punishment in order to achieve both peace and justice. In other words, judges’ discretion can be regarded as a field for implementing a deliberate policy aimed at providing informal concessions to Ukrainian state adversaries in the name of national reconciliation.

In order to verify this hypothetical assumption, we will look at the attenuating circumstances that accompanied less punitive decisions—accurate consideration of circumstances by a judge is more likely when a sentence is suspended, while unconditional sentences can be regarded as a “default option”— and to assess whether these circumstances relate to the goal of justice or that of peace.

We will take into account two groups of circumstances. The first group will be referred to as “legal”. These are circumstances that derive from provisions of the binding criminal code:

-

1. Low gravity of the committed deed. Here, we assume that persons whose deeds are relatively less harmful are treated in a less punitive manner.

-

2. Cooperation with the prosecution. Here, we assume that those who plead guilty or accept an agreement with the prosecution are treated in a less punitive manner.

The second group of circumstances will be referred to as “political”. These are circumstances which are not provided for in the criminal code, but which originate from the extraordinary nature of the circumstances under scrutiny:

-

3. The time when the wrongdoing was committed. Here, we assume that wrongdoings committed in the early stages of the conflict may be treated with leniency. As mentioned above, the most violent moments of the Donbas conflict were ended with the signing of the Minsk-1 and Minsk-2 agreements. Although neither of these agreements can be regarded as fully implemented, we assume that Ukrainian authorities may adhere to the contents of these documents in general, and to the loosely formulated amnesty provisions in particular. Additionally, one can argue that a certain deed committed in the “fog of war” associated with the initial, most violent phase of the conflict may be driven by the more or less authentic beliefs of the offender. In contrast, committing the same deed after an agreement to stop hostilities has been achieved can be regarded as an act of malice.

-

4. Proximity to the conflict area. Here, we assume that Ukrainian authorities may show sensitivity to the above-mentioned regional differences in public attitudes to possible solutions of the conflict (Democratic Initiatives Foundation 2019). Therefore, we can expect that courts situated closer to the area of conflict may issue less punitive decisions in an attempt to meet public expectations.

Clearly, one can argue that the above-mentioned circumstances do not represent the whole range of potential issues that may be taken into account by the judge when determining a sentence. Our proposal constitutes a compromise between numerous potential explanations of the outcome we are looking at, and the availability of information that was possible to extract from the documents used as data sources. Let us now turn to a detailed analysis aimed at revealing which set of circumstances stands behind the less punitive court decisions.

Note on the Methodology

The availability of a large number of documents opens the way for a comparative approach that can reveal regularities in the practice of issuing judgements. In the literature, there are examples of large-N comparative studies of court decisions (Holá, Smeulers, and Bijleveld Reference Holá, Smeulers and Bijleveld2009; Meernik Reference Meernik2003). Usually, such studies utilize statistical methods, and thus tend to make inferences about causality based on observed correlations; ultimately, they are aimed at creating a uniform “model” that explains the analyzed phenomenon and has some predictive power.

While the above-mentioned studies provided the inspiration for this particular research, we propose a different analytical approach—one based on Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA). In a nutshell, QCA examines set-theoretic relationships between causally relevant conditions and a clearly specified outcome. These relationships are interpreted in terms of necessity and/or sufficiency (Wagemann and Schneider Reference Wagemann and Schneider2007). To put it differently, the method is based on describing the cases under scrutiny in terms of their belonging to certain sets of conditions that are expected to lead to a certain outcome (which is also presented as a set). This is followed by a comparison aimed at identifying those conditions or combinations thereof, which can be regarded as necessary and/or sufficient for the outcome to emerge. QCA is based on set-theory, using Boolean algebra to minimize data. Unlike “conventional” statistical analysis, which is variable-oriented, QCA is case-oriented: it allows systematic comparison between cases, instead of comparisons across cases, and therefore is better suited to inductively built explanations (Meuer and Rupietta Reference Meuer and Rupietta2017). Another important and valuable aspect of QCA is the assumption of complex causality; in other words, it assumes that the outcome that interests us will not necessarily be explained by one “model” (Gerrits and Verweij Reference Gerrits and Verweij2013). Although QCA is usually regarded as a method appropriate for medium-N research, there are no obstacles to applying it to large-N datasets (Emmenegger, Schraff, and Walter Reference Emmenegger, Schraff and Walter2014).

The presented characteristics of QCA make it ideally suited to our research goal. The database at our disposal should not be regarded as a sample, but as a collection of information about the whole phenomenon in a certain period of time. This allows us to look at actual configurations of circumstances that accompanied actual court decisions. Furthermore, is not our intent to construct any sort of uniform model that would allow us to predict the outcomes of future court decisions. One should bear in mind that we are dealing with an ongoing conflict whose final outcome remains unknown. There is therefore no sense in searching for causalities that lead to a certain defined and well-established model of post-conflict TJ (at the moment of writing, the latter does not exist). We can only aim at understanding a certain situation that has emerged as a result of Ukraine’s four-year policy within the framework of its counter-terrorist operation. In other words, we are looking for repeated configurations of attenuating circumstances that may explain less punitive decisions taken by Ukrainian courts, assuming that the very presence of some clear patterns may determine the future development of a comprehensive approach to post-conflict TJ.

Finally, when analysing court decisions, one should bear in mind that it is an essentially complex issue. Despite frequent similarities, court decisions are unique; each judgement is issued upon weighing different circumstances in which the assessed action has been committed. Put differently, at least to a certain extent, a court decision involves assessing the set of circumstances in which the accused has committed a certain action, in order to assess the actual level of guilt. From this perspective, the advantage of QCA is obvious, as it focuses exactly on identifying the configurations of conditions explaining the outcome under scrutiny.Footnote 5

Due to space limitations, we will leave more in-depth explanation of QCA aside. Those interested may find more details in the literature constituting the methodological background for this research, provided by Schneider and Wageman (Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012) as well as Rubinson (Reference Rubinson2019). We utilize software elaborated by Oana and Schneider (Reference Oana and Schneider2018).

Selection of Cases for Analysis and Calibration of Data

In order to focus on the difference between less and more punitive court decisions resulting from the judge’s right to suspend the sentence of imprisonment, we exclude from the comparison those cases in which suspension was not formally possible: cases in which the accused was found not guilty, cases in which the accused was found guilty but was not sentenced to imprisonment, and cases in which the accused was sentenced to more than five years in prison. As a result, we obtain 241 cases of political wrongdoings and 1,137 cases of combatants’ wrongdoings.

Calibration of available data constitutes the first step of QCA analysis. The essence of this process is simple: one should assign a numeric value to each case, reflecting the level of membership of the case in sets representing the explanatory conditions and outcome under scrutiny. The value can vary between 0 (the case is fully out of the set) and 1 (the case is fully within the set). Assigning intermediate values is acceptable, if we deal with so-called “fuzzy sets,” situations in which there are reasons to regard something as being “partially in” or “partially out” of a given set.

In our case, sets will correspond to the legal and political attenuating circumstances discussed above:

-

1. Low gravity of a committed deed (coded “LOWGRAV”). Full membership (1) in the set is given to all cases where the offender is convicted for only one crime. Therefore, all cases where several crimes are present, and consequently the number of guilty convictions is higher than one, are excluded from the set (membership = 0).

-

2. Cooperation with the prosecution (coded “COOP”). Full membership (1) is given to cases where the convicted pled guilty or a plea agreement with the prosecution was reached. The rest of the cases remain outside of the set (membership value = 0).

-

3. The time when the wrongdoing was committed (coded “EARLY”). Full membership in this set (1) is given to cases where a crime was committed before February 2015 (the time of signing the Minsk-2 agreement). Consequently, all other cases are excluded from the set (membership value = 0).

-

4. Proximity to the conflict area (coded “CLOSE”). This is the only fuzzy set among our explanatory conditions. The value of membership in the set reflects the rounded proportion of the population in a given oblast of Ukraine convinced of the need for compromises, as reported in research by the Democratic Initiatives Foundation (2019). As a result, all cases are either partially in (0.8; 0.6) or partially out (0.4) of the set (in other words, a case is given a membership value of 0.8 if the decision is issued in the oblast of Ukraine where 80 percent of the population is ready to accept compromises with government adversaries).

Finally, as for the outcome that interests us (coded “SUSP”), the set contains all cases (membership value = 1), in which the sentence of imprisonment was suspended. The rest of the cases are excluded from the set (membership value = 0).Footnote 6

Tables 1 and 2 present truth tables for the analyzed cases of political wrongdoings and combatants’ wrongdoings, respectively. Truth tables reflect all logically possible combinations of explanatory conditions and an outcome, and the distribution of actual observations across these combinations. As one can see, some rows in the truth table remain blank—these are so-called logical remainders, combinations of conditions that are logically possible, but are not observed in reality. The consistency score in the truth table reflects the degree to which cases observed in reality actually fit into an ideal set defined by a given truth table row. Using the language of set-theory, the score reflects the degree of membership of empirically observed cases characterized by a given combination of conditions in the ideal set described by these conditions. This score is important for the analysis of sufficiency, which will be conducted in the following step.

Table 1. Truth table for instances of political wrongdoings

Table 2. Truth table for instances of combatants’ wrongdoings

Analysis of the Necessary and Sufficient Conditions for Issuing Less Punitive Court Decisions

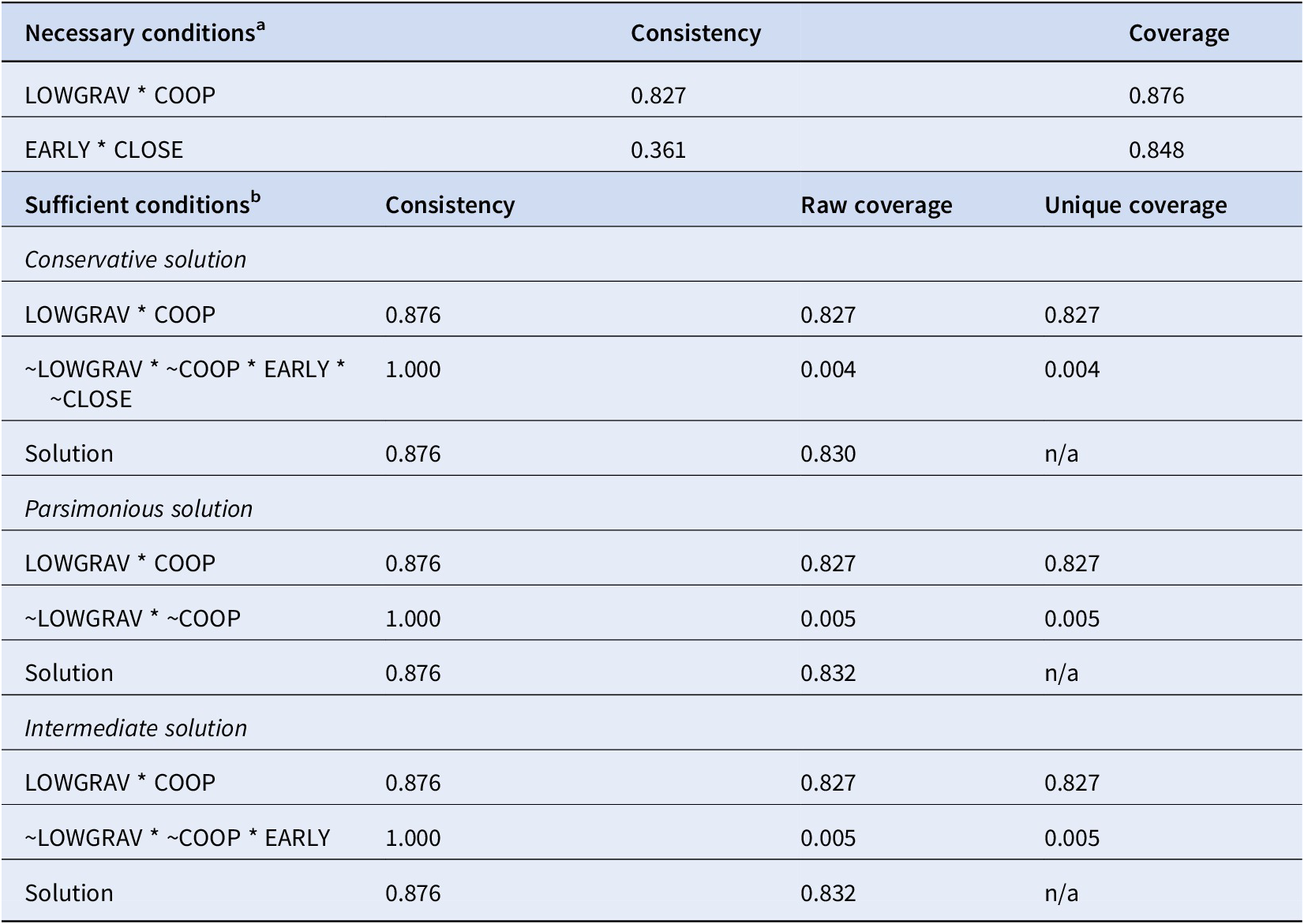

Tables 3 and 4 present the findings regarding the necessary and sufficient conditions for less punitive decisions in cases of political wrongdoings and combatants’ wrongdoings, respectively. Let us interpret these results.

Table 3. Necessary and sufficient conditions for suspended prison sentences: instances of political wrongdoings

a Consistency threshold: 0.9, coverage threshold: 0.7.

b Frequency threshold: 1; consistency threshold: 0.8. Tilde (~) identifies negation (lack of condition).

Table 4. Necessary and sufficient conditions for suspended prison sentences: instances of combatants’ wrongdoings

a Consistency threshold: 0.9; coverage threshold: 0.7.

b Frequency threshold: 1; consistency threshold: 0.8. Tilde (~) identifies negation (lack of condition).

Necessary conditions are conditions (or combinations of them), without the occurrence of which the outcome we are looking for cannot be achieved. In terms of set relationships, a necessary condition is the superset for an outcome. Taking into account the specificity of our subject of analysis (court decisions), it is logical to assume that a conjunction of attenuating circumstances should fulfil the criteria of necessity rather than any condition on its own. Therefore, we did not analyze the necessity of individual conditions, but of “models” presenting conjunctions of previously identified conditions. The “legal model” represents a conjunction (expressed by the logical operator AND, reflected with the help of *) of attenuating circumstances labelled above as “legal” ones: low gravity of committed deeds and cooperation of the offender with the investigation (LOWGRAV * COOP). Correspondingly, the “political model” represents a conjunction of “political” attenuating circumstances: committing a crime during the most intensive period of warfare and decisions being issued by a court situated in the direct vicinity of the conflict area (EARLY * CLOSE).

As we can see, neither model is necessary to provide less punitive decisions for political wrongdoings. In the case of combatants’ wrongdoings, the legal model can be regarded as fulfilling the criteria of necessity as defined by Schneider and Wagemann (Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012): simultaneously exceeding the threshold values of 0.9 for consistency and 0.7 for coverage. Surpassing these numbers suggests that the empirically observed relevant cases strongly correspond to the ideal set described by the model (consistency score), and that the set containing the outcome is not much smaller than the set containing the conjunction of conditions—otherwise, one may argue that the tested model is simply trivial (coverage score).

In other words, the conjunction of attenuating circumstances of a legal nature indeed resulted in less punitive decisions regarding persons who decided to engage in anti-government activities, later classified as terrorism or participation in illegal armed formations.

As we do not aim to find a “holy grail” of one universal rule explaining the difference between more and less punitive decisions of Ukrainian courts; analysis of sufficiency should prove more informative. In particular, the search for sufficient conditions can reveal multiple pathways leading to the outcome under scrutiny. These are combinations of conditions that are enough to explain the outcome observed in some cases, but at the same time do not constitute any sort of universal rule that explains all cases. In terms of set relationships, a sufficient condition constitutes the subset of an outcome.

In order to indicate sufficient conditions, the truth table should be subjected to the process of logical minimization. Following methodological suggestions by Schneider and Wagemann (Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012), we will exclude from this process those truth table rows which do not exceed the consistency score of 0.8 (i.e., only those rows in which empirically observed cases have a membership value of at least 0.8 are taken into account). This step should allow us to focus on cases in which the defined conditions are indeed relevant, taking into account the specificity of our object of analysis (there is a multitude of other conditions that potentially lead to a certain judgement, which may be “hidden” from us in this particular research).

The software allows us to generate three types of result, or solution formulas. The difference between them is in how we treat logical remainders. The conservative solution excludes logical remainders from the procedure of minimization; the parsimonious solution includes them; and the intermediate solution is a result that also includes logical remainders, but at the same time allows us to specify the directional expectations for each condition—it allows us to assume whether a given condition should contribute to an outcome when it is present or when it is absent. In our case, all conditions are expected to contribute to less punitive court decisions. Following the established good practices in QCA, we pay attention primarily to the intermediate solutions. Here, once again, one should take into account two parameters of fit: consistency and coverage. As already mentioned, consistency reflects the degree to which one piece of empirical information deviates from the perfect subset relationship (the higher the value, the less the deviation). Coverage indicates how much of the outcome is covered by the condition. Raw coverage indicates how much of the outcome is covered by this particular solution. Unique coverage indicates how much of the outcome is exclusively explained by this particular solution.Footnote 7

In the case of political wrongdoings, the analysis suggests the existence of two causal pathways that lead to less punitive decisions. The first of them presents the conjunction of both legal attenuating circumstances: low gravity of a committed act and cooperation with the prosecution. The second suggests the potential importance of the timing of committing a wrongdoing: there are cases where less punitive decisions were issued to persons who committed more than one wrongdoing and did not cooperate with the prosecution, but whose action was committed in the initial stages of the armed conflict. The low coverage score here indicates a small number of cases that followed this pathway. At the same time, the high consistency scores of each solution indicate that these combinations of conditions almost always led to a less punitive decision being issued by the court.

What is noteworthy, in the case of combatants’ wrongdoings, is that all three solutions appear to be similar, which is explained by the fact that there are no logical remainders—all possible combinations of attenuating circumstances can indeed be observed in reality. Furthermore, there are only two truth table rows which lead to the outcome we are interested in. As a result, the analysis suggests the existence of only one conjunction of conditions that can be regarded as sufficient for a court to issue a less punitive decision: low gravity of committed deeds, cooperation with the investigation, and committing a wrongdoing in the early stage of the conflict. This outcome corresponds with the previous analysis of necessity, but provides a slightly more nuanced picture: the time of committing a crime did matter to those who actively resisted the Ukrainian authorities as a mitigating condition in court.

The higher number of causal pathways explaining a suspended sentence in the case of political wrongdoings can be interpreted as an effect of the potentially wider margins for discretion in this sort of cases, as previously mentioned. On the other hand, fewer causal pathways explaining a suspended sentence, in the case of combatants’ wrongdoings, signals a more consistent approach of the judiciary to this type of wrongdoing.

Discussion

The analysis conducted suggests that, facing the extraordinary circumstances of armed conflict in Donbas since the beginning of 2014, Ukrainian authorities have not implemented any deliberate policy of leniency towards those supporting centrifugal tendencies in the Ukrainian state. The dominant majority of government adversaries who faced trial in court were convicted. Less punitive decisions (in the form of suspended prison sentences) can be explained by attenuating circumstances that are derived from existing legal norms, not from the specificity of the conflict situation itself. In other words, we found evidence to show that facing the extraordinary circumstances of armed conflict, Ukrainian courts have tended to pursue the goal of justice in its most narrow sense: they have punished the government’s adversaries based on existing legal provisions and have not used the tools at their disposal to sacrifice this goal for the sake of peace. The only exception here is a degree of sensitivity to the time of committing wrongdoings: in some cases, courts might have taken into consideration the fact that a given deed was committed in the “fog of war” when issuing a less punitive decision. This consideration was never decisive, though. Committing a wrongdoing in the early stages of the conflict can be regarded as a so called INUS condition (an insufficient but necessary part of a condition which is itself unnecessary but sufficient for the outcome) in part of analyzed cases. At the same time, another “political” condition that was expected to serve as an attenuating circumstance – the geographic location of courts – appears irrelevant.

It is important to underline several limitations that suggest that these findings should not be treated as “absolute truth” and at the same time signal potential directions for further research. First and foremost, there are limitations of a technical nature, which result in a certain level of imperfection in the data. Ukrainian experts point to technical deficiencies of the register (Pavliuk Reference Pavliuk2017), such as frequent technical problems with access, numerous mistakes in the classification of documents, and irregular publication of new documents. Therefore, some relevant documents may be missing—this is a force majeure that simply cannot be overcome. Furthermore, some documents in the register are classified and thus inaccessible; in such cases, court decision entries in the register are left blank. Consequently, no information was extracted from such documents. We cannot rule out that this “hidden” information may be significant enough to alter our findings.

Secondly, there are limitations that originate from our approach to the collection of data. Among the court decisions retrieved from the register, there appeared to be no cases referring to pro-government fighters, although there are instances of investigations against persons serving in the pro-government volunteer battalions that were spontaneously created at the beginning of the conflict. Theoretically, there are grounds to treat such formations as illegal armed groups (Pavliuk Reference Pavliuk2017). This fact does not prove the existence of any guaranteed impunity for this category of persons—they are often accused of crimes, which are described above as “compatible” with the time of peace (Dorosh Reference Dorosh2016), and therefore are not covered in our database because of the virtual impossibility of identifying them systematically. In view of our research objective, we can conclude that the CCU provisions penalizing participation in illegal armed formations were only used effectively against anti-government combatants. A comprehensive analysis of the approach of the Ukrainian state to wrongdoings committed by pro-government forces requires different research design.

Last but not least, among the court decisions retrieved from the register, there was no evidence of so-called “big fish” cases (persons belonging to a narrow group of high level separatist leaders). This fact does not in itself prove that the leaders of the “people’s republics” enjoy impunity—there are ongoing investigations against them, none of which were concluded within the study period. Therefore, it is persons who can be called middle- and low-level wrongdoers who constitute the primary object of retributive actions implemented by the Ukrainian state. The approach towards the above-mentioned “big fish” is yet to be analyzed, and the result of such analysis may shed more light on our empirical questions.

Conclusions

The analyzed decisions issued by Ukrainian courts in cases that refer to ongoing armed conflict in Donbas provide an interesting example of how legal tools designed for ordinary circumstances are applied in circumstances that are essentially extraordinary. Our analysis suggests that, in their attempts to answer the peace-versus-justice dilemma, Ukrainian authorities made a bid for the latter.

This state of affairs creates a framework for elaborating a model of post-conflict TJ in the future. In our opinion, it suggests that amnesty is likely to be granted to those who have committed the types of crimes discussed in this article. Ukrainian authorities seem to punish their adversaries in a consistent manner. During the first four years of the conflict, the authorities have not been inclined to grant any concessions to their adversaries that could be justified by the circumstances of armed conflict and acted in a manner that can be called “legalist.” It would be hard to modify this approach in the future based on political considerations without inducing feelings of injustice, and thus undermining the goal of reconciliation. Therefore, the most obvious solution would be simply to remove the criminal liability for this group of persons. Of course, the exact design of such an amnesty cannot be deduced from our analysis.

We are aware that the presented research does not provide answers to all possible questions. We treat it as the first step into the proposed research field, and as an invitation for other researchers to join us in this effort. Our analysis has raised several problematic issues, which require further research in order to shed more light on addressing the legacy of the Donbas conflict.

First of all, we are aware that our data are far from perfect. In particular, traces of political motivations standing behind judicial practice manifest themselves, not only in the documents reflecting the final decision of the court, but in earlier stages of investigation. It would therefore be worth conducting a study that could, for example, trace randomly selected cases from the outset. Whether such research is feasible remains unclear. Naturally, it would require access to all the materials of a given case, and this is unlikely to be possible.

Second, it would be worth studying the decisions referring to serious crimes which are “compatible” with peaceful circumstances, although this would require a different approach to the extraction of data. Based on what we discussed, this field in particular would allow the systematic analysis of differences in patterns of approach to anti-government and pro-government fighters participating in the conflict.

Third, as soon as (and if) courts issue decisions referring to “big fish” cases, the analysis of them will significantly contribute to our understanding of Ukraine’s approach to retributive justice in the context of the Donbas conflict. The much smaller number of cases will allow more detailed qualitative analysis to be conducted.

A final question worth addressing is how Ukrainian public opinion perceives the discussed court decisions. Essentially, this question relates to the goal and function of retributive justice, and asks whether the efforts of Ukrainian judges have produced any learning effects (e.g. have the decisions deterred any potential wrongdoers from engaging in anti-government activity? Have those affected by the conflict gained any sense of satisfaction from the issued judgements? Are these judgements considered to be just by society?).

All in all, the Donbas conflict is a case well worth further attention, as it may extend our knowledge about the principles and regularities that influence the approach to justice in the extraordinary circumstances of an armed conflict, and the significance of this approach for the process of reconciliation.

Disclosure Statement

Author has nothing to disclose.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the National Science Centre, Poland; under Grant 2016/23/D/HS5/02600.

Acknowledgments

Open access of this article was financed by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland under the 2019-2022 program “Regional Initiative of Excellence,” project number 012 / RID / 2018/19.