I Introduction

This article aims to introduce an institutional approach to understanding state-minority relations, which is currently absent in the academic literature. It does so through the application of an institutional analysis framework to the case study of Roma communities to explain how post-1989 Slovakia developed its institutional framework for national minorities. I will begin by introducing the context of Roma communities in Slovakia as an example of a minority group residing in the periphery of Slovakia’s territory. The article will subsequently demonstrate the absence of an institutional approach to state-minority relations by critically engaging with the dominant regime- and rights-based approaches. Following from this, and drawing from the work of Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990) and Skocpol (Reference Skocpol1979) on institutional change, I will outline a proposed framework of analysis. I will use this analytical tool to map the institutional evolution and change and to analyze the processes and mechanisms via which the institutional framework of state-minority relations has altered from the socialist to post-socialist period in the context of Roma communities in Slovakia. This will be demonstrated in terms of both radical and incremental institutional change.

II Roma Communities in Slovakia

Roma communities represent a substantial minority within Slovakia’s population. They live without a kin state, in the periphery of the state, and face challenges of political, social, and economic marginalization. Traditionally, the Roma are semi-nomadic groups that live off craftsmanship tied to local economies and have faced periodic attempts to forced settlement through history. These culminated during the Second World War through policies of forced physical segregation and racial extermination, which separated them from their socioeconomic ties (Kollárová Reference Kollárová and Vašečka2003).

With Czechoslovakia’s post-war socialist regime aiming for full industrialization of the economy, the Roma’s traditional sources of income almost disappeared. If they had been separated from the economic, social, and political life by force during the war, they were forcibly integrated in the socialist system of the economy through the policy of social integration, which essentially meant socioeconomic assimilation (Lužica Reference Lužica2016; Jurová Reference Jurová and Vašečka2003). There is a general consensus on the positive impact of guaranteed employment and an associated improvement of living standards, as well as prospects for social mobility. There is, however, disagreement over the balance between opportunities for Roma to rise within the social hierarchy and the negative impact on identity, as well as institutional racism that placed Roma primarily in the low-skilled section of the economy. Following federalization of Czechoslovakia in 1969, the Slovak government possessed its own institutional agency for design and implementation of policies vis-à-vis Roma communities, and therefore the Velvet Divorce of Czechoslovakia in 1993 did not result in any significant divergence from the existing process (Jurová Reference Jurová and Vašečka2003).

Post-socialist transformation associated with democratization and integration of Slovakia into Europe led to the recognition of Roma as a national minority. Though this provided them formally with equal collective rights as held by any other group, it also pushed a large proportion of Roma into marginalized settings as a result of economic transformations (Jurová Reference Jurová1999; Radičová Reference Radičová2001; Marcinčin and Marcinčinová Reference Marcinčin and Marcinčinová2009). In this regard, the situation of Roma communities represents a developmental challenge for a contemporary state, and thus Roma communities constitute an interesting case for an institutional analysis of state-minority relations.

III Theoretical Approaches to State-Minority Relations: Introducing an Institutional Analysis Framework

The general academic literature lacks a rigorous application of institutional analysis to the context of state-minority relations. The dominant stream of literature focused on state-minority relations uses regime-based and rights-focused approaches, which see institutions merely as factors or outcomes (Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka1996; Higgins Reference Higgins1984; Jamal Reference Jamal2009), while others look at a specific issue, such as development projects (McDuie-Ra Reference McDuie-Ra2011) or resettlement and land reform (Lestrelin, Reference Lestrelin2011). These all focus more on the agency of the minority groups or take a more general historical overview approach in a specific context (Jung Reference Jung2002), without application of an analytical framework that could be replicated elsewhere. Kymlicka’s (Reference Kymlicka1996) Liberal Theory of Minority Rights covers multiple relevant areas, from representation to rights to decentralization, while Jamal (Reference Jamal2009) applies Kymlicka’s framework to the context of Israel. However, they both omit the institutional agency and concrete mechanisms of change. The same omission is present in Higgins’ (1984) analysis of ideology and material distribution as key features defining state-minority relations in the course of regime change in Iran.

In the context of Roma communities in Slovakia, a comprehensive institutional analysis approach was equally absent. Studies have covered different elements of institutional analysis in specific historical episodes. For example, Lužica (Reference Lužica2016) provided a historical overview of institutions and policies vis-à-vis Roma from 1968 to 1989, Kusý (Reference Kusý1994) looked at minorities from the perspective of internal and external security in early 1990s, Dostál (Reference Dostál2006) analyzed how the change of government affected status of minorities in mid-2000s, Smetánkova (Reference Smetánková2013) compared governmental policies in 1993–1998 and 2006–2010, Jurová (Reference Jurová1999) provided an overview of policy development in 1990s, and Šutajová (Reference Šutajová2019) detailed the process of drafting and passing the Law on National Minorities and the role of the Government Council in 1968. Although each of the above studies was valuable in its own respect, be it in relation to a particular policy area or historical episode, their very focus did not allow them to tackle the more fundamental institutional questions such as the evolution and change of the institutional framework over a larger period of time. A more comprehensive historical institutionalist approach was partially filled by Zoltan Barany’s (Reference Barany2002) work, The East European Gypsies: Regime Change, Marginality, and Ethnopolitics, in which he analyzed the position of Roma within different regimes (imperial/authoritarian, state-socialist, and emerging democracies) across the time and space of Eastern Europe. While very successful in providing the overall picture, the book faces a certain conceptual oversimplification (for example, description of the regime types), which is understandable given the broad scope of the study. Still, it focuses more on the impact of the state institutions on Roma rather than on the institutional mechanism and processes. From more recent studies, Vermeersch’s (Reference Vermeersch2013) analysis of the EU’s policy developments vis-à-vis Roma and Sardelić’s (Reference Sardelić2021) socio-legal approach to Roma marginalization in Europe from a citizenship perspective are worth highlighting for their comprehensive contributions to understanding different institutional developments. However, they focus on Europe as a unit of analysis and offer sectoral perspectives in a more limited timeframe.

Therefore, these approaches are more static and do not answer many fundamental questions that this study aims to explore – namely: What were the factors and mechanisms of change of the institutional framework of state-minority relations? To what extent has there been a continuity or discontinuity? In which ways has the role and interaction of international, national, and local actors altered? Are these changes grounded in ethnic or distributional conflict, and what have been the specificities of the political settlement(s)?

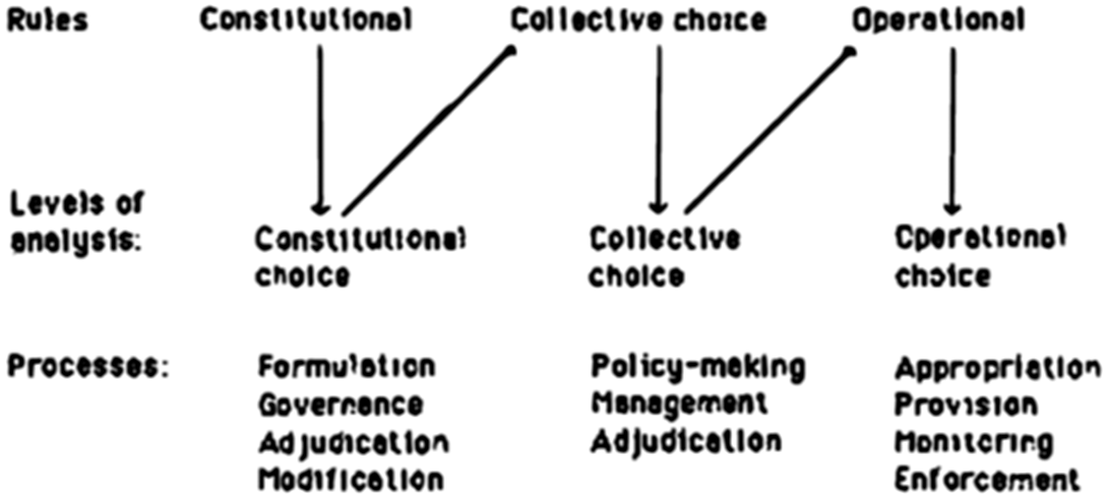

As for the analysis of institutional change, without undermining the value of the existing studies mentioned above, I aim to account for these nuances by proposing a framework based on different elements from the work of Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990) and Skocpol (Reference Skocpol1979). More specifically, I distinguish between radical and incremental institutional change. The former is associated with larger processes of social, economic, political, and international transformation, whereas in the latter collective mechanisms of decision-making as well as concrete institutional change mechanisms are the key focus of the analysis. The incremental change will be analyzed via prisms of multi-level institutional analysis of Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990), who specifically looked at the management of common-pool resources. Ostrom distinguished between constitutional-choice rules, collective choice rules, and operational-choice rules, thus allowing for the analysis of the top echelons of the system of governance to be linked with the local level implementation, as per figure 1.

Figure 1. Ostrom’s (Reference Ostrom1990) model of multi-level institutional analysis

Skocpol’s (Reference Skocpol1979) work is relevant to this study as she explored social revolutions and state transformations. Such changes characterize the post-socialist transformations of 1990s, when state-minority relations and their institutional framework were radically redefined. Skocpol analyzes four units of analysis in her work: 1) state-building, looking at both the sources of revolution and the outcomes; 2) socio-political structures; 3) socioeconomic legacies; and 4) world-historical circumstances and international relations. For the purposes of this study, I reframe these units of analysis as 1) state-economy transformation; 2) state-society transformation; 3) state-politics transformation; and 4) international transformation.

For the incremental change, the Ostrom-based framework, specifically her multi-level analysis, is more relevant. She defines the first level as constitutional-choice rules, which, as she explains, “affect[s] operational activities and results through their effects in determining who is eligible and determining the specific rules to be used in crafting the set of collective-choice rules that in turn affect the set of operational rules” (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990, 52). Hence, the constitutional-choice rules refer to the broader institutional framework and hierarchies that are outlined in the diagram as formulation, governance, adjudication, and modification. Ostrom describes the second layer of analysis as “collective-choice rules,” that is, the rules or decision-making mechanisms through which policies are made, including management and adjudication (Reference Ostrom1990, 52). Finally, the last level in Ostrom’s framework is referred to as “operational rules” or the rules that “directly affect the day-to-day decisions” (Reference Ostrom1990, 52) and imply the processes directly related to implementation mechanisms, appropriation, provision, monitoring and enforcement.

While I utilize the different levels of analysis from Ostrom’s framework, I adapt the different components and units of analysis outlined above in line with how I define an institutional framework in this study: 1) policy and legal basis, 2) state institutional structures (general and specialized) and other organizations, and 3) policy initiative, design, decision-making, and implementation. These institutional mechanisms are then used to map the evolution of the institutional framework of state-minority relations in the context of Roma communities in Slovakia.

IV Methodology and Data Collection

The study takes an institutional mapping and historical analysis approach using a case study method. This is proposed in this article as the most appropriate for an understanding of the institutional developments of state-minority relations, which can be observed in figures 2 to 10. It is only by understanding the context of institutional frameworks and observing institutional processes over a relatively large time span (in the case of this study, from 1969 to 2020) that is it possible to establish the mechanisms and dynamics of institutional change. This is particularly relevant during periods when major transformation processes were taking place and the new Slovak state was developing new institutional frameworks.

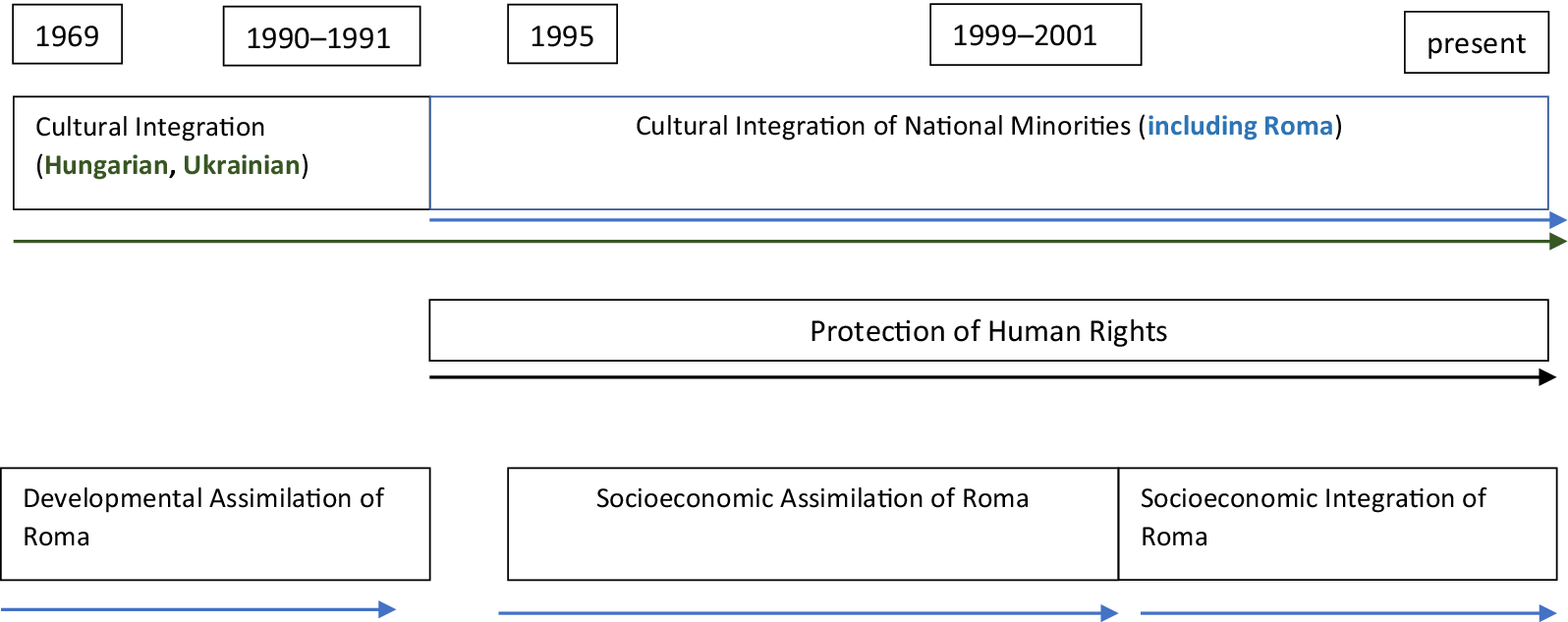

Figure 2. State Policy vis-à-vis Minorities in Slovakia in the pre-1989 period and post-1989 period. The diagram shows different policies toward Roma from the officially recognized minorities in the pre-1989 framework. After 1989, Roma were recognized as an official minority, which implied cultural policy and human rights protection; however, the socioeconomic policies vis-à-vis Roma that had previously been dominant completely disappeared in early 1990s and were only reintroduced from the mid-1990s.

This article draws empirically from data collected for a PhD project on Institutional Dynamics of State-Minority Relations in the Broader Post-Soviet Space. The methods used combine primarily in-depth semi-structured interviews with document analysis. The data gathered is further substantiated with available quantitative data and other ethnographic insights collected during fieldwork in Slovakia for triangulation purposes. The interviews were conducted in January and February 2020 both in the center, Bratislava, and in peripheral regions of Slovakia, where Roma predominantly reside. A diversity of representatives from different agencies were interviewed, including individuals working in specialized and general state structures, municipalities, NGOs, academic and research institutions, international organizations, as well as individuals from Roma communities themselves. Special attention was paid to interviewing not only those respondents who were active in recent years but also those active in the 1990s and 2000s. To complement the different narratives and insights from the interviews, I explored government documents from the late socialist period in the Archive of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, as well as archival documents that outline the role of international organizations in the transformation period of the 1990s from the OSCE Documentation Centre in Prague.

V Evolution and Change of Institutional Framework(s) of State-Minority Relations in the Case of Roma Communities in Slovakia

V.I Pre-1989 Institutional Framework

The pre-1989 institutional framework for minorities was conceptually inspired by the Soviet rationale of categorization between nations, nationalities, and ethnic groups. The most significant framing period was the one around 1968 and 1969, during the Prague Spring and federalization of the state. Therefore, the focus is primarily on the period between 1969 and 1989, for it was this institutional framework that was changing in the transformation processes following 1989. The framework in Czechoslovakia, as highlighted in figure 2, was notably characteristic of the division between institutional framework in terms of cultural policy for the officially recognized nationalities, specifically Hungarian and Ukrainian, and developmental assimilationist policy for Roma. While a more detailed historical overview of the former can be found, for instance, in the work of Šutajová (Reference Šutajová2019) and Gabzdilová (Reference Gabzdilová2013), this study is going to focus on the latter, the case of Roma. For the purposes of mapping of the evolution and change, the previously outlined definition of an institutional framework is used: 1) policy and legal basis, 2) state institutional structures (general and specialized) and other organizations, and 3) policy initiative, design, decision-making and implementation

From the policy and legal perspective, the pre-1989 institutional framework for Roma was characteristic of the changing nature of the policy as well as practically non-existent legislative grounding. Firstly, the policy transformed from focusing on forced assimilation in the 1950s and 1960s to a more proactive multi-facet assimilation strategy from the 1970s onward. Jurová (Reference Jurová and Vašečka2003) describes how the initial measures targeted the dismantling of settlements, immediate participation in the economy and education, and subsequently from 1965, the relocation of Roma. Due to the lack of success of the earlier policy and temporary change of circumstances prone to reforms surrounding the Prague Spring period, the new strategy was restructured to a more complex set of measures. These included 1) pre-school and primary school participation; 2) enrollment in high schools, vocational training, and universities; 3) cultural development and social activities of Roma youth; 4) edification; 5) employment; 6) living conditions; 7) social mobilization and relations with the majority (42/1976 SSR Government Resolution). Although the wording used in the strategy implied social and cultural integration, the policy was essentially assimilationist, aiming to raise the socioeconomic status of Roma to that of the majority population, and not the cultural development of Roma as such. In addition, there was also a separate strategy for Roma delinquency (234/1977 SSR Government Resolution), which was still primarily overseen by the Ministries of Interior and Justice and the Prosecutor General. These were meant to cooperate with other ministries, such as the Ministry of Culture, or local bodies and actors including boards of commissioners and social workers, to provide basic legal education to Roma. Therefore, there was a clear change from a repressive to a more proactive socioeconomic policy focus.

Secondly, in contrast with the legislative basis for the officially recognized nationalities, there was a genuine underdevelopment in the case of Roma. One of the very few pieces of legislation was the 74/1958 Zb. Law on the Permanent Settlement of Nomadic Individuals, as pinpointed by Jurová (Reference Jurová and Vašečka2003) and Lužica (Reference Lužica2016). Even though neither the title nor wording in the law mentions Roma or Gypsies, as they were called at the time, the law specifically targeted these communities. Similar to the case of the nationalities in the earlier period described above, the resolutions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party constituted important documents that directed the policies. However, from 1960s onward, the policy was grounded exclusively in the numerous government resolutions, from which above-mentioned 42/1976 included Principles of the Nation-wide Socio-Political Measures Concerning the Societal Care of the Gypsy Population is only one example. Such form of legislative grounding provided the state with a considerable extent of flexibility, which can be observed also in the respective documents that were continuously being adapted. In addition, Roma communities should not be perceived only as passive recipients of these policies for as early as from the 1950s. Indeed, there were efforts from amongst Roma appealing to the government for recognition and more rights. Such efforts were unsuccessful however, with the exception of the brief period from the late 1960s to the early 1970s (Donert Reference Donert2017; Jurová Reference Jurová and Vašečka2003).

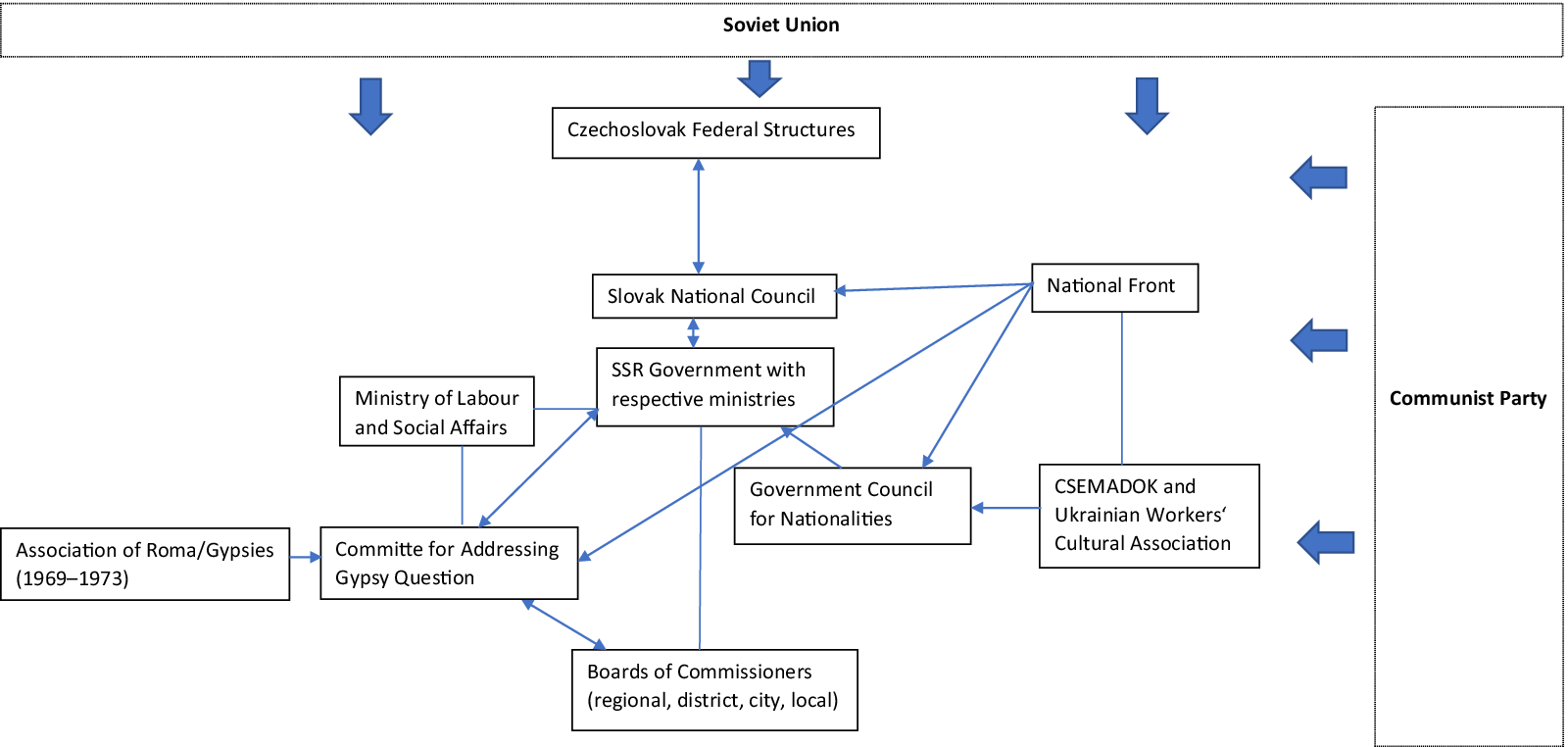

Regarding the role of institutional structures and organizations in policymaking and implementation, the initiative and design were primarily led by the Communist Party in the initial years. (For a detailed organizational overview, see figure 3.) From the late 1960s onward, these processes were led by the specialized consultative bodies, most notably the Government Committee for Addressing the Question of Gypsy Population under the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs. In the brief period following the Prague Spring, the policy initiative was instead arguably driven by the Roma organizations. The policy implementation was delivered predominantly by the general institutional structures of the state, shifting from the Ministry of Interior in 1950s and 1960s to the Ministry of Labor from late 1960s onward. In the case of Roma, the institutional structures and organizations were the following: 1) Government Committee on the federal level from 1965 to 1968 and subsequently Government Committee for Addressing the Question of Gypsy Population under the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs of the Slovak Socialist Republic from 1969 onward, as advisory bodies to coordinate the relevant activities were examples of the specialized state institutional structures; 2) organizations, namely a) the Communist Party and b) Association of Roma/Gypsies that operated from 1969 to 1973, as well as Butiker, which was a state enterprise under the management of the Association of Roma/Gypsies in the same period (Lužica Reference Lužica2019); c) general organizations, such as trade unions, state enterprises, youth organization, housing collectives etc., and 3) general state institutional structures, with hierarchies and inter-connections outlined in figure 3.

Figure 3. Institutional Framework for National Minorities and Roma in Slovakia, 1969–1989. Institutional structures and organizations reflected the socialist policies vis-à-vis national minorities, with a strong hierarchical state in the middle as well as division between specialized structures and organizations for Roma and other minorities, which can be observed on the positioning of the Committee for Addressing Gypsy Question under the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs. The small arrows display influence or agency in between different structure, either in one or both directions, while the large arrows show overarching but necessarily direct influence.

In terms of the role of institutional structures and organizations in policy initiative, policy design, and decision-making, the relevant documents, such as the 74/1958 Central Committee of the Communist Party Resolution on Work in Gypsy Population highlighted by Jurová (Reference Jurová and Vašečka2003), suggest these processes were overseen by the party in the initial years. From 1965, the responsibility moved to the federal-level Government Committee and following federalization, to the Government Committee for Addressing the Question of Gypsy Population under the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs of the Slovak Socialist. Additionally, from 1969 to 1973, a representative of the Association of Roma/Gypsies had a seat on the committee. It was therefore arguably this association, as Lužica (Reference Lužica2019) shows, that was the driving force of the policy initiative. The design was primarily pursued by Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs as the institutional structure overseeing the committee, but notably in consultation with other ministries and bodies – not only due to their presence on the committee but also, as the archival materials suggest, because of the complexity of the policy agenda requiring their input and resources. However, more in-depth archival research into the meetings would be needed to identify exact policy agency or agencies in this regard. Furthermore, similar to the case of the national minorities, it is hard to identify exact loyalties on an individual or even organizational basis. Jurová (Reference Jurová and Vašečka2003) and Mann (Reference Mann and Rafael2020) show that the Secretary of the Government Committee, who was himself Roma, was in favor of assimilation and against any initiatives focused on Roma culture. Based on archival research, Lužica (Reference Lužica2019) explains how disagreements amongst the leadership of the Association of Roma/Gypsies contributed to the end of the organization. As for the decision-making, these were done formally by the government, as the government decrees suggest, yet the Communist Party still played a key role in the most important matters. For instance, it was the decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party to dismantle the Association of Roma/Gypsies in 1973 (Lužica Reference Lužica2019).

Finally, the implementation was delivered predominantly by both general and specialized state structures as well as other organizations. In the initial years, the policy of forced assimilation and relocation was under the auspices of the Ministry of Interior, for example, as outlined in article 5 of the 74/1958 Zb. Law on the Permanent Settlement of Nomadic Individuals, where the Ministry of Interior and Justice were to oversee the delivery of the principles state in the law. Therefore, the shift of responsibility for the agenda under the Ministry of Labor was an important one and corresponded with the changing understanding of the policy as multi-faceted, focusing particularly on proactive socioeconomic rather than repressive measures. Furthermore, the archival documents show that the Government Committee had assigned representatives at regional, county, and local level boards of commissioners, which thus constituted another form of important institutional structure within the state hierarchy involved in the implementation process. More generally, given the broad scope of the policy, the involvement of a particular institutional actor delegated in the implementation depended on the concrete policy area such that the Academy of Sciences was responsible for research, the Ministry of Education for schools, and the universities for education, the housing organizations and construction enterprises for housing, the labor unions for state enterprises, and the collective farms for employment, and so on. In addition, another important implementation mechanism was funding, which was all directed from the state budget. According to Lužica’s (Reference Lužica2016) research, the annual costs of the programs in the period 1976–1984 were 247,65 million CSk. To put it into perspective using the inflation and conversion calculator of the Institution of Economic and Social Reforms (INEKO n.d.), the sum would nowadays equal slightly more that 78 million euro.

V.II Post-1989 Institutional Framework

Following the outline of the pre-1989 institutional framework of state-minority relations, this section will discuss the one that developed in the period after 1989, with a focus on Roma communities.

Firstly, the policy vis-à-vis Roma after 1989 has prompted diverse understanding. The three primary categories, which appeared across the interview responses, can be described as following: 1) socioeconomic integration; 2) cultural rights and emancipation as a new distinct feature coming with the recognition of Roma as one of the 13 official national minorities; and 3) human rights. These are displayed in figure 2 for the relevant time periods. It was a lengthy process following 1989 until these were understood as interconnected rather than separate policy areas. The primary features of the post-1989 policy in the initial years had been diversification and change, with three phases: 1) cultural emancipation with socioeconomic dimension omitted (1990/1991–1995), 2) socioeconomic assimilation (1995–1998), 3) socioeconomic and cultural integration (1998 onward). The first two are comfortably summarized in an interview with the former Plenipotentiary for Roma Communities (2010–2012) and civil society activist, Miroslav Pollák:

After 1989, there was an attempt to tackle the so-called Roma problem either culturally, meaning through support of their ethnicity and cultural features – let’s give them a theater, language, newspapers, let them dance, let’s support their extracurricular activities, they are all good musicians, let’s leave them in their sphere. That was not sufficient. Another approach was a social one. Moving the whole issue under the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, and treating them like socially under-privileged citizens, groups, communities, or nationality as in 1990s they were already a nationality. But it did not succeed either. None of them worked because they were all separated. Betting all the money on a single horse. But the reality and life are more complex. (Pollák Reference Pollák2020)

The initial policy targeted cultural emancipation and identity of Roma via a focus on language, the development of cultural activities and organizations, press, and so on. These were all areas that were developed for officially recognized nationalities under socialism but not for Roma. At the same time, the socioeconomic policies characteristic of the socialist period were rejected. The 1991 Principles of Governmental Policy of the Slovak Republic vis-à-vis Roma underlined the official recognition of Roma as a national minority, and in the section on economic provisions, it argued against “special assistance to Roma based on belonging to Roma ethnicity, only to socially endangered strata of the population,” which effectively meant no policy in this sphere.

However, as Jurová (Reference Jurová1999) argues, with the worsening socioeconomic conditions in the first half of 1990s and international and civil society pressure, there was a need to address this issue. This led to the establishment of the Government Representative for Citizens Needing Special Help in 1995 (see figure 6). The latter’s strategy, outlined in the 796/1997 Government Resolution, reversed the earlier notion from 1991 and effectively associated poverty with Roma as a group. However, as shown in figure 2, this did not mean the rejection of Roma as a national minority in the general cultural policy of the state. Nonetheless, one of the interviewees, former Roma parliamentarian (1990–1992) and civil society activist, Anna Koptová, who was involved in some of the meetings stated that “they were cheated” when describing the outcome. The position under the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, together with the policy priorities – namely 1) upbringing and education, 2) culture, 3) employment, 4) housing, 5) social care, 6) health, and 7) prevention of anti-social behavior – was indeed a “déjà vu” from the past (Jurová Reference Jurová1999).

Finally, with the change of government in 1998, the Government Representative was renamed to the Plenipotentiary for Roma Minority and subsequently for Roma Communities, positioned under the Deputy Prime Minister for Regional Development and National Minorities and a strategy with a new set of policy areas, which combined the rights-based, socioeconomic, and cultural dimensions, was outlined: 1) human rights and rights of national minorities, 2) upbringing and education, 3) language and culture, 4) employment, 5) housing, 6) social affairs, and 7) health (821/1999 Government Resolution). An important difference from the earlier approach is that the target of such socioeconomic measures is labelled as Marginalized Roma Communities. Thus, Roma are defined by a deprived socioeconomic status. In other words, Roma are defined based on distributional grounds rather than ethnic affiliation. These areas remain effectively in place as the policy focus until today in all the other subsequent more or less developed strategies, which have, however, varied across different Plenipotentiaries and governments in office. In this regard, several interviewees highlighted lack of policy continuity, referring, for instance, to the Strategy of the Slovak Republic for Integration of Roma up to 2020 (2012), which was developed by a Plenipotentiary (2010–2012), Miroslav Pollák, then ignored by the subsequent Plenipotentiary (2012–2016), Peter Pollák, who had his own strategy targeting 150 selected municipalities, and returned to by a Plenipotentiary that followed (2016–2020), Ábel Ravasz.

Secondly, the legal framework for national minorities, including Roma, moved from “under-legislation” under socialism to “over-legislation” in the post-1989 period. One of the interviewees, the Secretary of the Committee for National Minorities and Ethnic Groups and the Director of Department of Rights and Status of National Minorities in 2019, Alena Kotvanová, described the legal situation in the following way:

Currently, national minorities are constitutionally protected. One whole section of the constitution covers the protection of the rights of national minorities. However, if we go slightly more in detail, then there is relevant legislation (laws) that is not so comprehensive. The language is protected by law. Other issues are partially addressed in various pieces of legislation. Their number is pretty high. That means that in terms of utilization of the legislation by members of national minorities is complicated to a certain extent (Kotvanová Reference Kotvanová2020).

Indeed, the Title 2 Section 4 of the Constitution of the Slovak Republic is dedicated to the rights of national minorities and ethnic groups. However, article 1 states that “A law shall lay down details thereof.” Unlike in the case of the pre-1989 period, the relevant provisions were outlined in numerous general laws, thus making the legal provisions difficult to understand or recognize for ordinary citizens belonging to national minorities. As described in the Legislative Intent of the Law on National Minorities – Rationale for a new legislation: Law on National Minorites ( 2020 ), the exception to this is the 184/1999 Law on the Use of Languages of National Minorities or 365/2004 Anti-Discrimination Act, yet a law defining the status of national minorities has not been passed since 1992. Another legislative dimension that emerged and arguably also shaped the national level legal framework is the international one. Notably, the two main documents, were the Council of Europe’s European Charter of Regional and Minority Languages in 1992 and the Framework Convention for Protection of National Minorities in 1994. Apart from the protection of the rights of national minorities, which the above provisions outline, socioeconomic policy vis-à-vis Roma continued to be grounded in government resolutions.

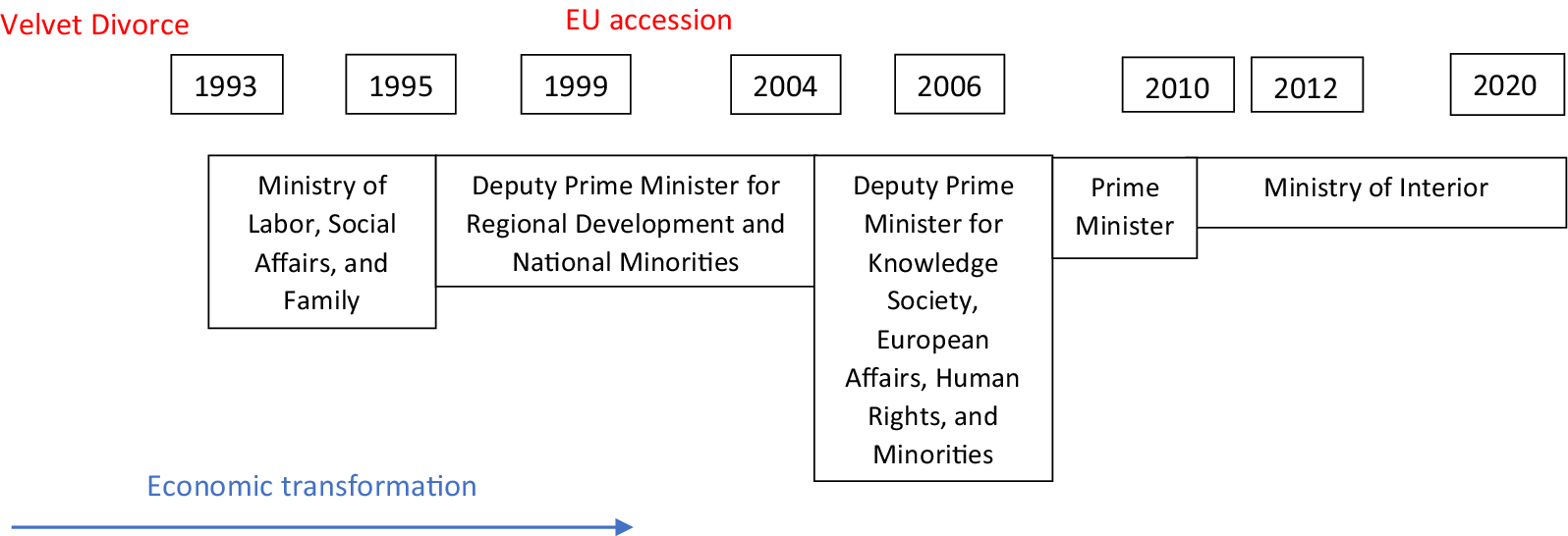

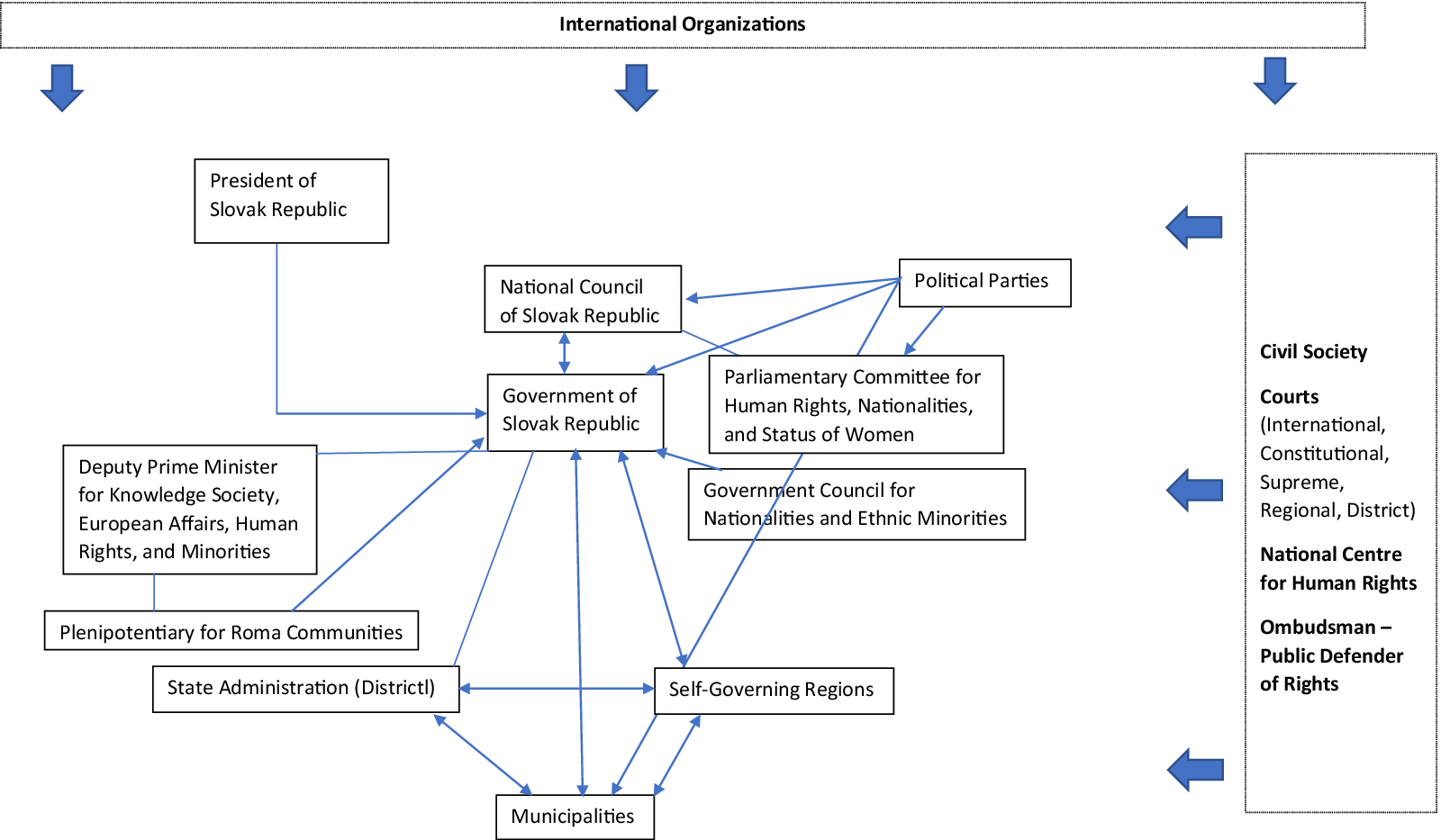

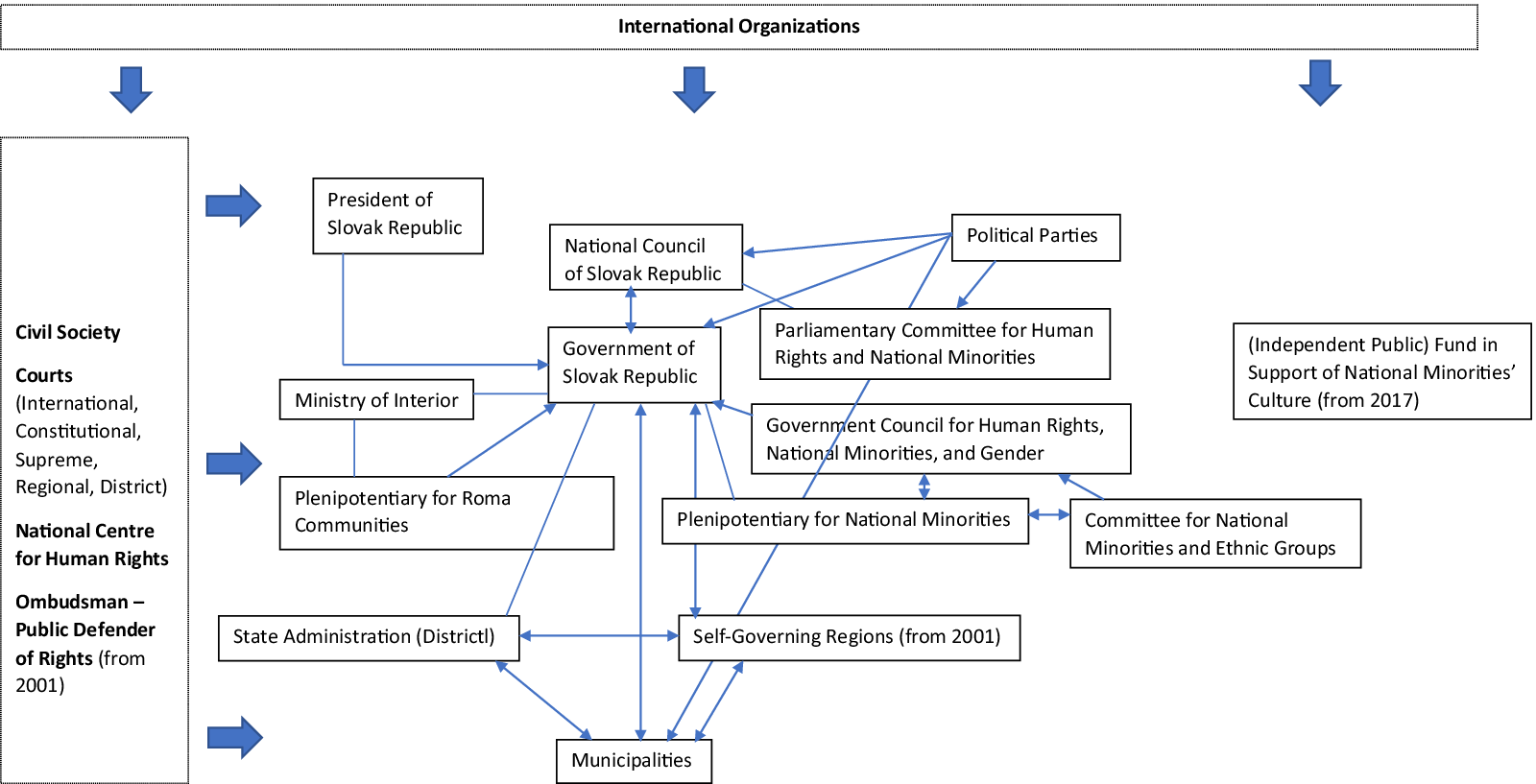

Thirdly, in terms of the role of institutional structures, organizations and mechanisms in policymaking and implementation, the whole institutional framework diversified and has also since been characterized by continuous change, as can be observed in figures 5 through 10. The milestones in the organizational change (1995, 1999, 2006, 2010, and 2012) reflect changes in the positionality of the Government Plenipotentiary for Roma Communities (highlighted in figure 4), which itself was an outcome of a change of government and commonly associated with changes in policy or at least implementation mechanisms. Based on the categorization I outlined, the sub-divisions in the post-1989 institutional framework changed in the following way:

-

1) The specialized state institutional structures are: a) consultative and governmental policy-coordinating body for Marginalized Roma Communities, whose position within the state structures moved from Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (1995–1998) to under the Deputy Prime Minister from 1998 to 2010, then Prime Minister from 2010 to 2012, from where the office came under the Ministry of Interior, where it remains till 2021, when it moved back under the Office of Government; b) Government Council for National Minorities as an advisory committee to the government reviewing policy and legislation regarding rights of national minorities with all 13 officially recognized minorities, including Roma, from 2010 turned to a Committee for National Minorities under the Government Council for Human Rights, National Minorities and Gender Equality, and thus to an advisory body of an advisory body, which includes representatives of different state agencies and civil society; c) consultative and governmental policy-coordinating body for national minorities, firstly under Deputy Prime Minister (1998 to 2012), and from 2012 a separate office of Plenipotentiary for National Minorites under the Government Office was created; d) a parliamentary committee, consisting of members of the parliament, with the remit to review relevant legislation on rights and policy vis-à-vis national minorities as a part of the parliamentary legislative procedure; and e) Fund in Support of National Minorities’ Culture established in 2017 as an independent public fund self-governed by national minorities, previously under the Ministry of Culture and the Government Office.

-

2) Organizations are a) political parties b) civil society organizations.

-

3) Public institutional structures are a) Apart from respective ministries, state institutional structures have operated at the below-national level either at regional or county level or both in different periods; b) self-governing regions (from 2002) and municipalities (towns, villages, city districts) as public institutional structures with directly elected leadership overseeing certain agenda delegated from the state as a part of decentralization process; c) President; d) human rights bodies – National Human Rights Centre and the Public Defender of Rights (Ombudsman); and e) courts.

-

4) International organizations constitute of a) public (e.g., European Union, Council of Europe, World Bank, OSCE); b) private (e.g., Open Society Foundation).

The diversification occurred on all levels of institutional mechanisms of both policymaking (initiative, design, and decision-making) and implementation. First, the sources of policy initiative after 1989 have ranged from international organizations primarily via soft power, expert advice, political pressure and funding opportunities, through civil society organizations or municipalities with their own micro-level policies or via various consultative mechanisms, to the state bodies, parliament, government and political parties. Second, the responsibility for design of the nation-wide policy has been primarily in the hands of specialized institutional structures, namely the Plenipotentiary for Roma Communities and a specialized institutional structure overseeing the agenda of national minorities, together with relevant consultative mechanisms. Third, in contrast with the socialist framework, decision-making dispersed across different levels of governance with each possessing electoral legitimacy as a result of decentralization and democratization, and with political competition among multiple political parties, and thus the institutional framework being potentially amended with every electoral term.

Figure 4. Changes to the positionality of the specialized state structure, an advisory body on Roma communities, within the government in independent Slovakia. Since 1999, the Plenipotentiary for Roma Communities of the Government of the Slovak Republic. Other milestone events, such as the Velvet Divorce, the EU accession, and the process of economic transformation are also highlighted on the timeline.

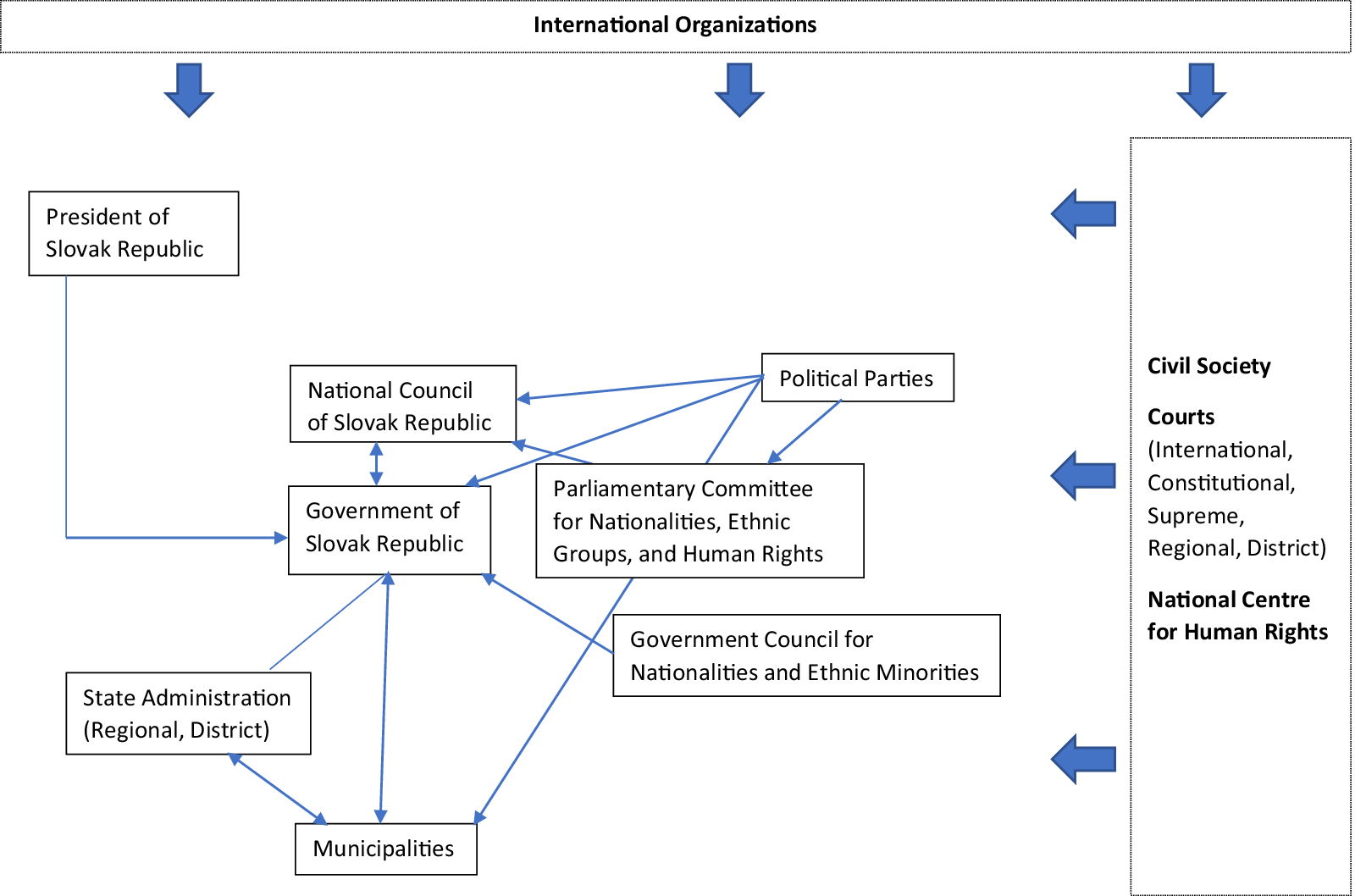

Figure 5. Institutional Framework for National Minorities in Slovakia, 1990–1995. The transformation period was defined by significant restructuring of the institutional framework, at the level of both general and specialized structures. The specialized structures for Roma disappeared. However, a number of new actors outside of the state hierarchy emerged, such as civil society organizations, political parties, international organizations and municipalities. This period was characteristic of economic transformation as well as the Velvet Divorce in 1993.

Figure 6. Institutional Framework for National Minorities in Slovakia 1995–1999. Specialized state structures for Roma were reintroduced, similar to pre-1989 positioning under the Ministry of Labor, Social Affairs and Family. From this period, the institutional change takes place at an incremental pace. In terms of political context, this period was defined by the rule of an authoritative Prime Minister, Vladimír Mečiar, who subsequently lost elections in 1998.

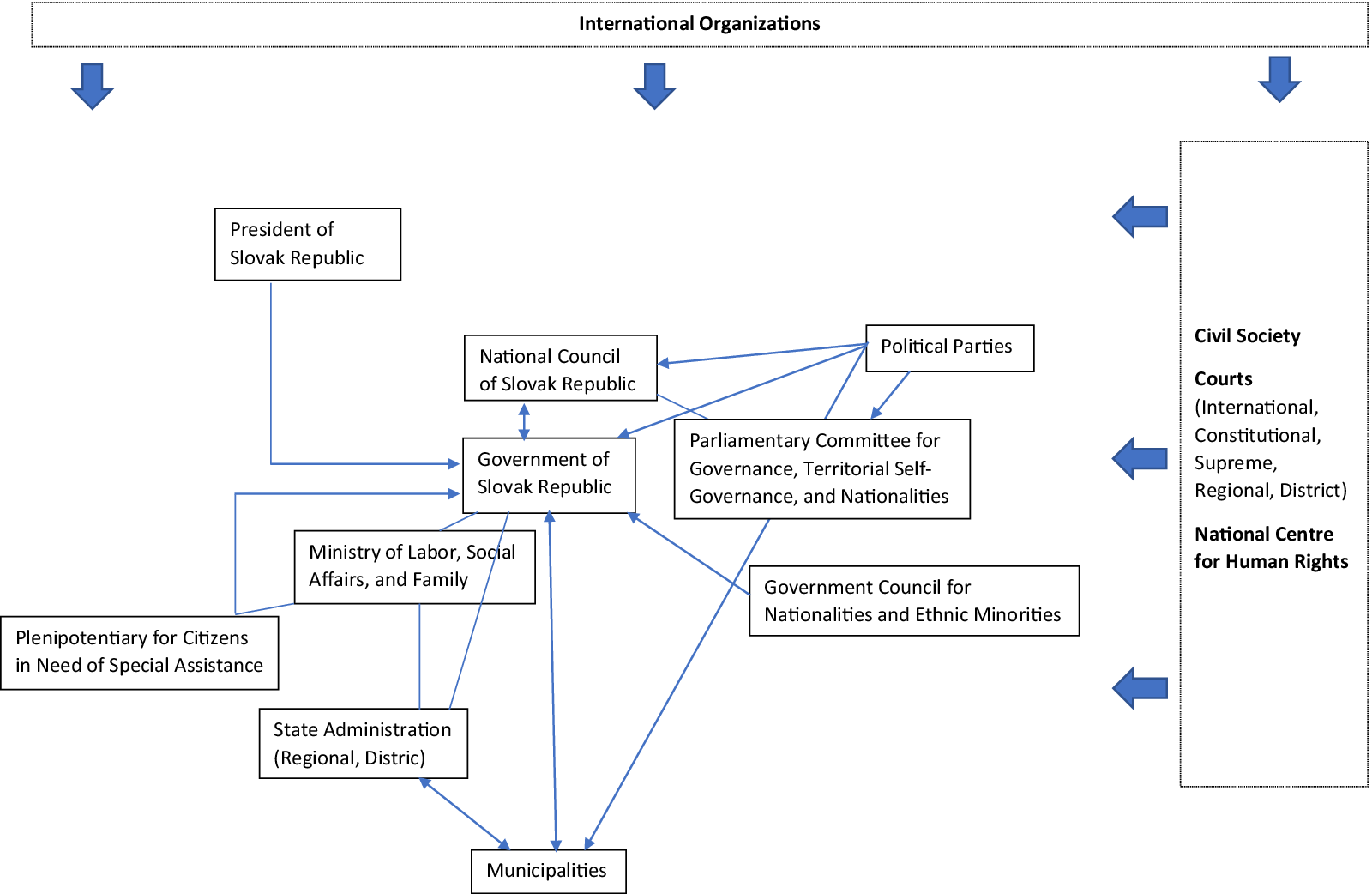

Figure 7. Institutional Framework for National Minorities in Slovakia 1999–2006. The specialized structure of the Plenipotentiary for Roma Communities is created and positioned under a Deputy Prime Minister. In terms of general structures, further decentralization of state power takes places, which is delegated to the level of Self-Governing regions. The Office of Ombudsman is established. In terms of the broader context, Slovakia joined the European Union in 2004.

Figure 8. Institutional Framework for National Minorities in Slovakia 2006–2010. No significant restructuring of institutional framework takes place, except for widening of the agenda of the Deputy Prime Minister, under whom the Plenipotentiary for Roma Communities is operating.

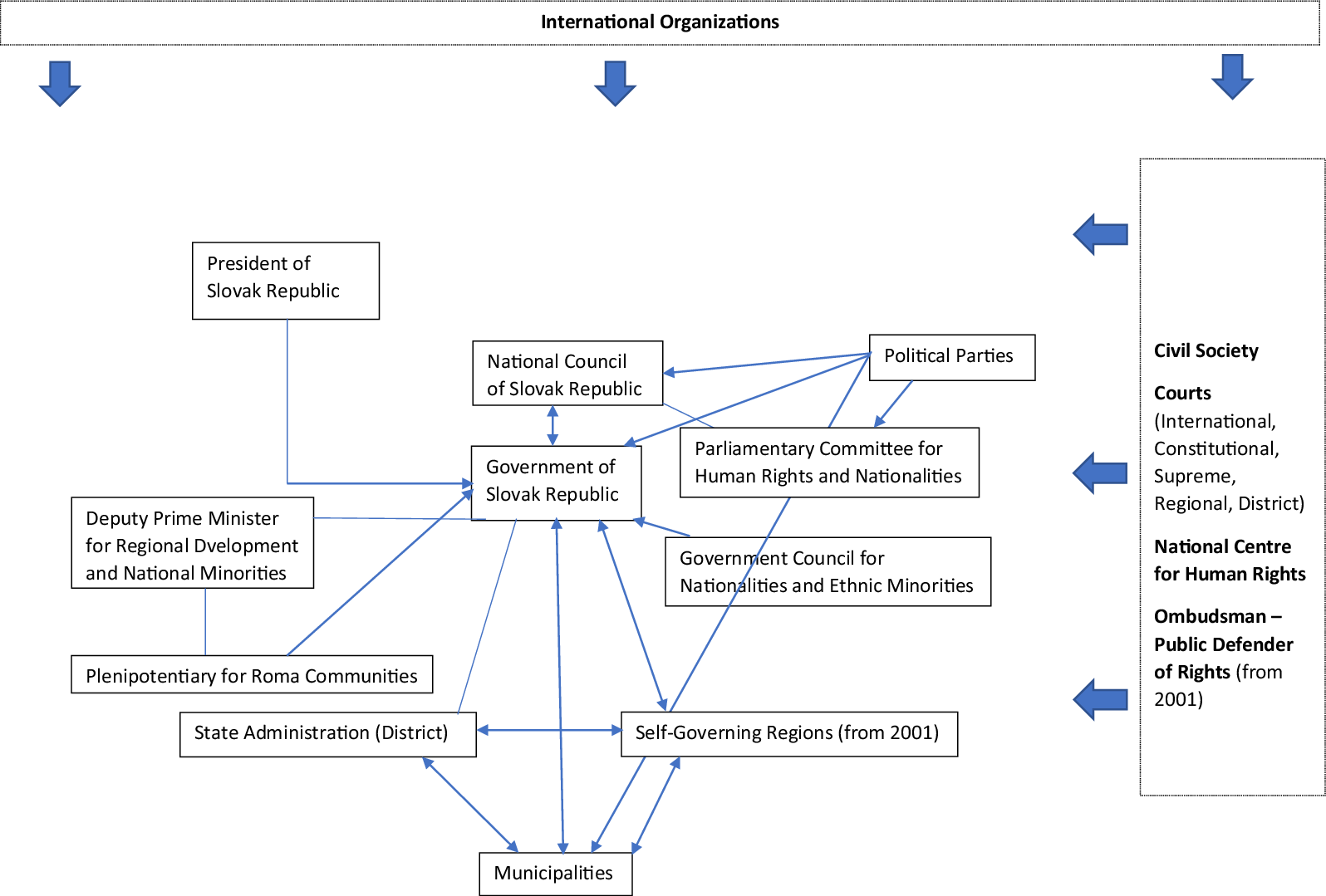

Figure 9. Institutional Framework for National Minorities in Slovakia 2010–2012. Governmental Council for National Minorities is merged with other agendas, and the issue of national issue demoted to the level of a committee.

Figure 10. Institutional Framework for National Minorities in Slovakia 2012–2020. The Office of the Plenipotentiary is repositioned under the Ministry of Interior, and the general agenda for national minorities is demoted from the level of Deputy Prime Minister to the level of Plenipotentiary for National Minorities. Independent Public Fund in Support of National Minorities’ Culture is established in 2017.

Finally, the implementation process in this area equally diversified in terms of actors involved as well as funding mechanisms. After 1989, the responsibility for the implementation moved from the general structures of the state to the municipalities and civil society actors, in accordance with the 1991 Principles of Governmental Policy of the Slovak Republic vis-à-vis Roma. Moreover, while the state was active in cultural identity building (and thus schools, theater, and media were established), there was little state support in the socioeconomic dimension in the initial years. As the interviews highlighted, the network of field social workers affiliated with the county level labor offices and committees was dismantled without any replacement introduced until 1996. In addition, the funding, which was previously exclusively provided by the state budget in the socialist period, observed a trend of a diminishing role of the state and an increasing role of international public and private mechanisms, which are dominated by the EU structural funds. Perhaps even more importantly, it changed from direct investment to a project-based system of financing, which will be discussed below. To put this into perspective, the EU contribution to the integration of Roma communities in the last programming period (2014–2020) constitutes around 400 million euro (European Commission n.d.,). This is slightly less on an annual basis than the amount dedicated to this policy area by state funds in the pre-1989 framework based on the figure mentioned earlier (Lužica Reference Lužica2016), using the inflation calculator.

VI Institutional Change of the Post-1989 State-Minority Relations in the Case of Roma Communities in Slovakia

As already mentioned, this study distinguishes between radical and incremental institutional change. The latter refers to gradual change, where collective mechanisms of decision-making and political settlements as well as concrete institutional mechanisms play a defining role. Radical institutional change, on the other hand, is associated with larger processes of social, economic, political, and international transformation. In the case of incremental change, Ostrom’s (Reference Ostrom1990) three levels of collective choice will be used as an analytical framework. The analysis of radical change is inspired by Skocpol’s (Reference Skocpol1979) structural analysis focused on state transformation via prisms of politics, economy, society, and international context.

VI.I Radical Change: Institutional Transformation

The main analytical focus of radical change is not on decision-making but rather on the larger processes and context in which the institutional change of state-minority framework for Roma in Slovakia took place. The focus lies more specifically in state-economy, state-society, state-politics, and state-international politics. Naturally, such large-scale changes do not happen often – they were arguably started but not finished in the brief 1968–1969 period, or in the 1990s, which will be the focus of the analysis. Although each of these processes had its own time span, and though they practically lasted until the last wave of economic transformation was completed in the early 2000s, new functioning of civil society developed, the last decentralization measure was put in place, and Slovakia joined the EU. I will focus on the processes that carried relevance for state-minority relations, and specifically Roma, based on interview findings and secondary literature.

VI.I.I State-Economy Transformation in Slovakia

This section analyzes the transformation of the institutional framework for Roma in the context of state-economy relations. The primary focus will be the significant increase in unemployment among the Roma, which is contextualized within the rapidly declining role of the state in the economy and the transformation of the public policy and welfare system.

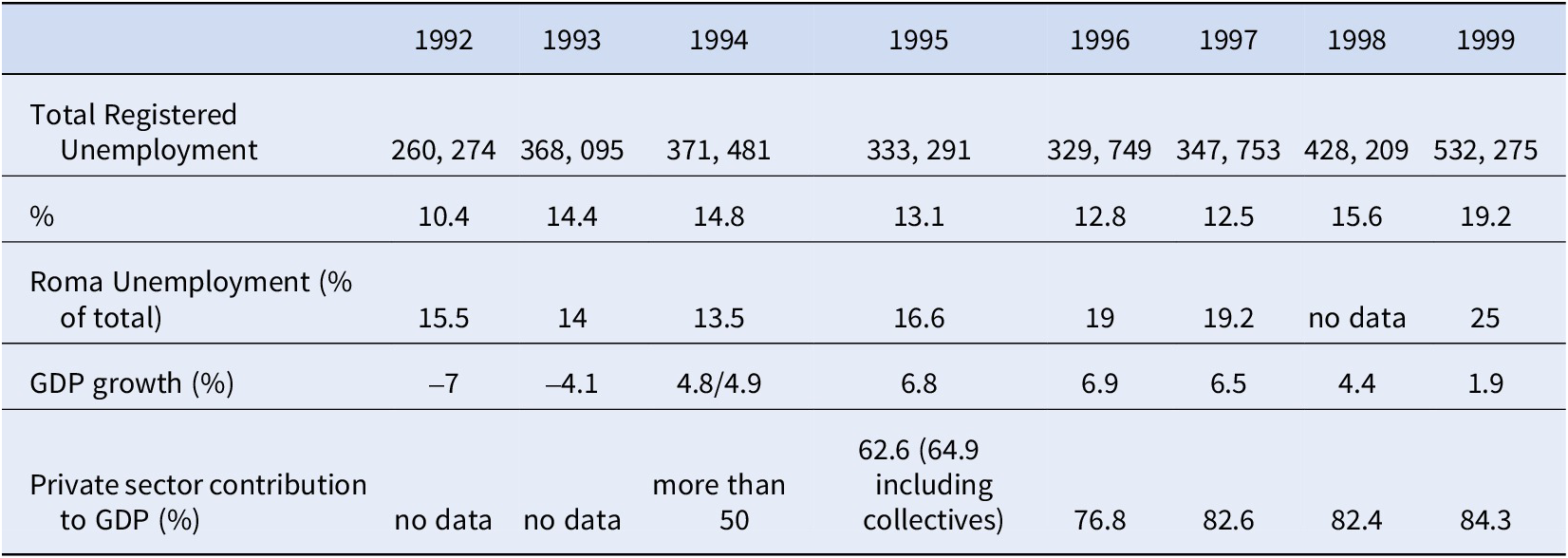

Much has been written about the economic transformation, including liberalization, privatization, and other associated processes in 1990s. There is now a general consensus on its negative impact on society, including on the Roma, which was evidenced primarily through a significant rise in unemployment (Jurová Reference Jurová1999; Radičová Reference Radičová2001; Marcinčin and Marcinčinová Reference Marcinčin and Marcinčinová2009). Table 1 outlines the total registered unemployment figures and the proportion Roma represented. The available data is only indicative as it includes the “registered” numbers. The actual numbers for Roma were likely higher. There is also a regional dimension to Roma unemployment, as Roma communities primarily reside in regions in the east of the country, which were hit by the transformation the most, as outlined in the National Bank of Slovakia’s Annual Report (1993). A Helsinki Watch report outlined that in one locality in eastern Slovakia, Rimavská Sobota, according to Dr. Okošová, “a worker at the local employment office… as of the end of 1991, out of 6,530 known unemployed persons in Rimavská Sobota, 4,289 were Romanies,” equating to roughly 66% (Human Rights Watch and Helsinki Watch 1992). In some localities, the employment among Roma was up to 100% (World Bank, S.P.A.C.E. Foundation, and INEKO 2002).

Table 1. Registered Unemployment, GDP growth, and private sector contribution to GDP in Slovakia, 1992–1999

Source: World Bank et al. (2002) based on original sources data from 1992–1998: National Labor Office and National Bank of Slovakia annual reports (1993–Reference Jurová1999)

Two interviewees explained the significant rise in unemployment, and particularly in the case of Roma, by the fundamental redefinition of the role of state in the economy. The state-economy dynamics was moving from paternalism in the pre-1989 framework to individualism in the case of after 1989. Roma parliamentarian at the time (1990–1992) and subsequently Roma cultural activist, Anna Koptová, explained the process of economic transformation in the following way:

Because the Democrats said that everyone is responsible for themselves since this is characteristic of democracy. Then, when you are self-sufficient and decide for yourself, you have freedom. But the conditions for it were not created. Businesses began to fire their employees, the Labor market relaxed in such a way that it did not need this kind of workforce, even though the men were qualified. (Koptová Reference Koptová2020)

This view was also shared by a former World Bank economist (2000–2008) and later Advisor to the Minister of Interior and Plenipotentiary for Regional Development, Anton Marcinčin, who represents an example of an interviewee from the center:

They were the first victims of the recession that occurred, perhaps necessarily, shortly after the Revolution, as they did not have sufficient qualification. Many new investments were poured into new technology that replaced them on the market… All in all, I think that paternalism was replaced by hard individualism. This individualism could have been there before, of course. (Marcinčin Reference Marcinčin2020)

The role of state in the economy was radically diminishing in the transformation years, as shown in increasing share of the private sector in GDP indicated in table 1, from more than 50% in 1994 to almost 85% in 1999. This happened through the privatization of state enterprises and a growing number of private ones, as well as rationalization, which led to an imbalance between the number of jobs lost and the number of jobs created. The state thus lost control over industrial policy and the labor market. As such, the central planning element disappeared, and therefore the state was no longer able to mitigate regional disparities. The result of these processes was a scarcity of jobs, which naturally led to competition between Roma and non-Roma, and essentially, a distributional conflict.

Marcinčin argued that “individualism” although present also before 1989 “was balanced by the presence of public policies of the state, which went into recession after 1989 to make way for a new naive form of capitalism. Consequently, … issues of equal opportunities and equal access have not been touched on since then” (Marcinčin Reference Marcinčin2020). Koptová added that, as a result, “Many Roma went for financial and social support, which was silly because it supported their inaction. Maybe those who made the decisions meant it well, but it turned out to be bad in those socioeconomic processes. They demoralized them” (Koptová Reference Koptová2020).

In line with the above, the transformation of the social welfare system happened in parallel to the decline of the state’s role in the economy. A Roma historian and politician, Zuzana Kumanová, outlined that

after 1989, as all the institutions were undergoing transformation, the committee was dissolved. I am not sure if it was dissolved in 1990 but I think it was, and so the system of social workers disappeared too. At the same time, there were certain structures operating under regional offices before 1989, which was later on taken over by Labor offices. But it was all dissolved in 1990s, because we were undergoing transformation, and so nothing in the social affairs (welfare) was left untouched and everything was changing. (Kumanová Reference Kumanová2020)

The 444/1990 Law on the Establishment of Labor Offices, without specifying the details, moved the remit over labor issues away from former regional boards of commissioners under the Ministry of Labor and from the county-level boards of commissioners under the county-level labor offices. The 1/1991 (Federal) Law on Employment claimed that these bodies were responsible for the facilitating of “full, productive and freely chosen employment,” which was defined as “one of the basic goals of the economic and social policy of the state.” The initial lines of the law followed: “Citizens have the right to employment irrespective of race, skin color, sex, language, religion, political or other beliefs, membership in political parties and affiliation to political movements, nationality, ethnic or social origin, property, health or age.” The legislation stated that this right was provided either via 1) “facilitating employment,” 2) “requalification,” or 3) social benefits, meaning the mechanisms through which the former system guaranteed employment were technically replaced with new ones.

However, in 1992 Helsinki Watch already reported practice of institutional racism both from employers and state bodies: “a significant amount of discrimination against Romanies by both state-owned and private enterprises, as well as a failure by some government employment offices to take action against companies with discriminatory hiring practices. Many Romanies complained that employers directly told them that they weren’t interested in hiring any Romanies” (Human Rights Watch and Helsinki Watch 1992). Therefore, if the labor office had not facilitated the employment or requalification, the last option was social benefits. As the interviewees highlighted, on the one hand this further heated the perceptions of the majority. On the other hand, as the employment benefits were limited to a period of 12 months, unemployed Roma were left without a source of income and pushed to unofficial economy and/or other coping mechanism, such as reliance of benefits of other kind (child care, disability benefits, etc.).

VI.I.II State-Society Transformation in Slovakia

Another important transformation process that shaped the institutional change in the post-1989 context was characterized by changes on the societal level, which will be discussed through three dimensions: 1) development of civil society; 2) emancipation of Roma; and 3) relations with the majority population.

Firstly, the process of civil society development after 1989 led to the creation of non-state actors, which play an important role in both policymaking and policy implementation. One can argue that there were elements of civil society and civil society actors in the socialist period even in the case of Roma communities, for instance the brief of period of Association of Roma/Gypsies, the civic initiatives lobbying for the recognition of Roma as an official nationality (Jurová 2003; Donert Reference Donert2017; Mann Reference Mann and Rafael2020) or the Charta 77 (Prečan Reference Prečan1990). However, these were often in disagreement with the state or sometimes persecuted. The Association of Roma/Gypsies (though not apolitical or independent of the state) acted as an exception to this rule and was formally institutionalized. Yet the legal and political circumstances during socialism did not allow for its continued existence, which was only possible after 1989. Indeed, the number of NGOs and private foundations of various size experienced significant growth in this period. Though some of these groups disintegrated early, 2002 data from the InfoRoma Foundation and Open Society Foundation demonstrates that the number of Roma organizations increased from 3 in 1990 to 223 in 2001 (Repová and Harakal, Reference Repová, Harakal and Vašečka2003). In this regard, there was also an increase in private funding. This funding came mostly from abroad, the prime example of which is the previously mentioned Open Society Foundation. However, many of the foreign agencies who came to Slovakia in the early 1990s eventually transformed into local civil society actors. That was also the case of the Carpathian Foundation and ETP Slovakia (previously Environmental Training Project for the Central and Eastern Europe), representatives of which were interviewed for this research. To put this into perspective, in the year 2000, Roma related activities funded equaled 60,000,000 Sk. by the state (Government of the Slovak Republic 1999, 22), 114,478,800 Sk. by the EU PHARE programs (European Commission no date 1, 22), and 10,480,721 Sk. by the Open Society Foundation (Marček Reference Marček2004, 22). The majority of interviewees from civil society, municipalities, and the state highlighted that civil society actors took over a lot of the agency in policymaking and implementation.

Directly related to the development of civil society explored above, the second crucial dimension on the level of societal transformation in 1990s was the emancipation of Roma. As a result of the official recognition of Roma as a national minority, such initiatives in the cultural sphere were developed with a direct state support. As Zuzana Kumanová, a Roma historian and politician recalls:

theater was established, and university program of Roma Culture was established in 1995. It was then renamed to the Institute of Roma Studies. There was the theater, newspaper was published, and other cultural activities were taking place. That was based on the resolution, and the fact that these cultural activities were financed from the state budget. The theater, the university program, they were both financed directly by the state. (Kumanová Reference Kumanová2020)

Similarly, the period is described by a former Roma parliamentarian and activist, Anna Koptová:

This was the time when elements such as identity development and support were emerging. The MPs approved the project of the first professional Roma theater in Slovakia. This theater, which coincidentally was in Košice and I was its first director, had a nationwide scope. It was under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture and it received full attention as did other theaters in Slovakia. This period was good for us because we had what we asked for depending on the extent to which we were able to do things. (Koptová Reference Koptová2020)

However, both expressed that the situation began to change again in the late 1990s when these activities were delegated to regional administration and the direct state support shifted to project-based financing. Nonetheless, it was the initial transformation period when the initiatives and organizations for the development of Roma culture and identity began in a more systemic manner.

Finally, the state-societal transformation also led to changes in the Roma relations with the majority and the rise of extremism. With the liberalization of the state and rise of social movements and initiatives, it was not just the non-governmental sector and Roma initiatives that developed. Equally other forms of social movements with negative perception toward minorities, based on either ethnic or distributional conflict, developed in tandem. As such, chauvinist rhetoric began to display itself also in the political competition. However, the Slovak National Party was the only party in parliament using such rhetoric at the time, and it targeted Hungarians in addition to Roma. While Vašečka (Reference Vašečka and Vašečka2003) argues that the majority’s general perceptions of Roma did not change on average, it is hard to compare given the lack of data from the pre-1989 period. Puliš (Reference Puliš and Vašečka2003), on the other hand, argues that there was an increase in the number of organizations with extremist and racist agendas in the 1990s. Such organizations, such as the skinhead movement (which started as early as 1990) were not previously able to operate. In addition, the number of reported hate crimes experienced a significant increase – from 19 in 1997 when they were first recorded to 102 in 2002 (Puliš 2003, 462). One of the Roma interviewees recalled how he was attacked by skinheads in this period.

VI.I.III State-Politics Transformation in Slovakia

This section will discuss the key processes of post-1989 state-politics transformation relevant to the institutional framework defining the state-minority relations in the case of Roma in Slovakia. The processes explored are democratization, decentralization and the political participation and representation of Roma. While the Velvet Divorce of Czechoslovakia in 1993 was an important milestone and arguably had an effect on all three processes, it did not fundamentally amend the key role of these processes.

Firstly, the democratization process allowed for political competition among multiple actors in the electoral process. Though elections and a variety of political actors were technically in place in the National Front, the “leading role” of the Communist Party was undeniable, and constitutionally grounded in article 4 of the 100/1969 Constitution of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. Therefore, political competition was occurring within the organization of the Communist Party rather than between organizations. After 1989, this was amended by the paragraph 4 of article 29 of the Constitution of Slovak Republic, which stated that “Political parties and political movements, as well as unions, societies or other associations shall be separate from the State” (460/1992 Zb. Constitution of the Slovak Republic). This change not only institutionalized the political competition, but also gave a stronger role to the legislative and executive bodies, namely the parliament and the government, in the decision-making process.

Secondly, the process of decentralization was effectively an extension of democratization on multiple levels of governance. In the pre-1989 framework, Boards of Commissioners existed at the regional, county, and town level. Board members were technically elected, and they were part of the state administration. However, the political competition was effectively limited to the Communist Party on multiple levels, and the decision-making followed a top-down hierarchical structure. During the post-1989 transformation, decentralization started as early as 1990 when the 360/1990 Law on Municipalities was passed, which allowed for the direct election of institutional structures of local governance. Political competition was no longer a question of competition between individuals but one that included competition between organizations. Equally, decision-making shifted toward the local level, which now occurred with greater legitimacy grounded in the electoral process (Nižňanský and Hamalová 2013). However, it was not until the early 2000s that further decentralization measures were introduced by establishing self-governing regions in 2002 and increasing the remit of municipalities (Nižňanský and Hamalová 2013). The majority of interviewees highlighted that apart from civil society actors, it is the municipalities who play the key role in institutional change through policymaking and especially policy implementation. However, those representing municipalities stressed that their responsibilities were not sufficiently matched with remit and financial capacities, suggesting that functional decentralization has not been completed.

Thirdly, the post-1989 developments were characterized by the underrepresentation of Roma in politics and their slowly developing participation in public life, despite the free political competition at the national and local levels enabled by the new institutional framework. In terms of political representation, there were Roma members of legislative bodies at the national level from 1990 to 1992, and subsequently only after 2012. However, in both cases, individuals were candidates of mainstream parties rather than an elected Roma political party. Interviewees suggested that Roma political movements and parties fractured due to disagreements among the leadership and non-uniformity among the Roma communities. This can be confirmed through the number of political organizations: as of 2002, there were 20 of them registered with the Ministry of Interior (Šebesta Reference Šebesta and Vašečka2003, 209). On the municipal level, there is a limited data for initial years, although there were arguably Roma representatives among mayors and members of municipal assemblies (Mušinka et al. Reference Mušinka2014). As a result of the municipal elections in 1998, there were 5 mayors and 56 members of municipal assemblies elected across Slovakia (Šebesta 2003, 206–207). This was followed by a gradual increase in the subsequent elections, with more than 40 mayors in office at present (Kumanová Reference Kumanová2019). However, all Roma interviewees agreed that political representation at the national level is critical for institutional change. In this regard, one of the interviewees, Anna Koptová, stressed that Roma representation in that foundational period was essential in pushing through the legal recognition and state support for emancipation via political settlement.

VI.I.IV International Transformation and Its Impact on the State-Minority Relations in Slovakia

Just as the new states underwent transformation in early 1990s, international organizations experienced a process of institutional change in the new post-Cold War context. For instance, the CSCE (Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe) was being transformed from a conference into a new international organization, OSCE (Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe), whereas the Council of Europe was expanding its membership to Eastern Europe as well as another portfolio of activities. Such institutional change at the organizational level also applied to the sphere of national minorities. During the initial years, the process revolved around the establishment of a new international institutional framework via the establishment of both binding and non-binding norm-setting documents, as well as institutional structures and mechanisms. Slovakia was impacted by these processes by nature of undergoing accession to these organizations.

The agency of international organizations in this period played an important role and was substantiated primarily through 1) expert advice and 2) purpose-specific funding mechanisms, as the provision of funding depended on policy conditionality.

Such agency of institutional change held by international organizations was also highlighted by some of the interviewees, who suggested that the specialized institutional structure for Roma was created as a result of conditionality from international organizations, and the EU in particular. This aligns with a report on the Contemporary Situation of the Roma National Minority in Slovakia from November 1996, from the OSCE archives, which was presented to OSCE Parliamentary Assembly by the Slovak Delegation. The document attempted to make a case to the international community for the proactive measures the government was taking vis-à-vis Roma communities in Slovakia, particularly with respect to the specialized body of the Government Representative for Citizens Needing Special Help.

Other OSCE archival documents shed further light on the role of international organizations, particularly the OSCE High Commissioner for National Minorities, in the process of institutional change shaping the framework of state-minority relations. In a 1994 letter to Slovak Foreign Minister, Eduard Kukan, the High Commissioner provided very direct legislative and policy recommendations in the areas of participation and representation of the minorities in decision-making, administrative reform, use of language in public places, teaching, and the administration of schools. Even though the High Commissioner did not consider the situation of Roma to fall under his mandate (Kemp Reference Kemp2001) – and as such he addressed these issues primarily in the context of Slovak-Hungarian relations – the recommendations were related to and were to apply to national minorities in general. Therefore the mechanisms naturally impacted the Roma as well.

In addition, apart from policy conditionality, the funding mechanisms had a direct policy impact as they were structured around concrete policy areas and priorities, both regionally and with a country-specific focus. From 1994 to 2001, the total amount of PHARE funds spent on Roma-related activities equaled almost 20 million euro, with increasing dedication to such activities evidenced by 75% of the sum being spent in the last three years of this period (EU Commission n.d. 1, 22–23). The thematic focus varied across the spectrum, from infrastructure to democracy building to support for civil society or from cultural development to education and training (EU Commission n.d. 2, 22–23).

VI.II Incremental Change: Institutional Mechanisms and Political Settlement

The complexity of the incremental institutional change following the post-1989 transformation can be demonstrated by an example: On June 27, 2019, the parliament passed the 209/2019 Amendment to the Law introducing compulsory pre-school education. The measure was the initiative of the Government Plenipotentiary for Roma Communities, Ábel Ravasz. As his office does not have the remit of a legislative proposal, it was proposed by a group of three coalition members of parliament, although the agenda falls under the Ministry of Education; and thus the Minister of Education would traditionally oversee the governmental legislative proposals in this sphere. Even though the law applies to all children, the goal with respect to Roma communities is to ensure integration with the majority population and a smooth entrance to the mainstream educational system – as opposed to specialized one for pupils with mild mental disabilities. Roma children are often wrongly diagnosed and placed in such schools, a phenomenon which was highlighted in several interviews and for which Slovakia has been facing Infringement Proceedings from the European Union. The Plenipotentiary recognized that “the law constitutes only the elementary framework, which needs to be developed with relevant support measures. Kindergartens need to be built, new teachers and assistants hired, and work with families accentuated” (Ministry of Interior of Slovakia 2019). This essentially corresponds with the distinction between formal institutional change, and one implemented in practice. One of the interviewees from the periphery, a Roma mayor of a village in Eastern Slovakia with a population of roughly 3,000 people, half of whom are Roma, described the local-level complexities over the course of the implementation of this law. He drafted a project proposal for the construction of a new kindergarten in response to a funding call by the Operational Program Human Resources, made for this purpose and administered by the Ministry of Interior, as the capacity of the existing kindergarten was not sufficient to accommodate all the children in the village, including Roma. When the proposal was drafted, it stated that 30% of the capacity would be dedicated to Roma children, but it was rejected by the financial committee of the municipal assembly, as the majority population did not want their children to attend the same kindergarten as Roma children. As a result, they drafted another proposal for the construction of a new kindergarten in the proximity to Roma settlements in the village. The outcome is that there are currently two kindergartens, one for Roma and one for non-Roma children – thus going against the goal of the intended institutional change (Anonymous Roma mayor 2020).

In order to analyze the decision-making dimension, I apply Ostrom’s (Reference Ostrom1990) three-level analytical framework of collective choice. In this regard, she distinguished between three levels of analysis, namely constitution-choice rules, collective-choice rules, and operational rules. Firstly, as Ostrom outlines, “constitutional-choice rules affect operational activities and results through their effects in determining who is eligible and determining the specific rules to be used in crafting the set of collective-choice rules that in turn affect the set of operational rules” (1990, 52). Therefore, the constitutional-choice rules refer to the broader institutional framework and hierarchies, which are effectively outlined in the diagrams. The only times when these were amended in the case of Slovakia was the period of 1968–1969 when the federalization and constitutional recognition of nationalities was introduced, and in the 1990s possibly extended to the early 2000s when the institutional transformation was taking place. In the case of the pre-1989 institutional framework, they were the constitutional pieces of legislation setting the status of national minorities, the leading role of the Communist party, as well as the top-down hierarchical structure of the state. Following this logic, within the respective constitutional-choice arrangement, Roma should not have had the Association of Roma/Gypsies, yet interestingly they did. In contrast, the constitutional-choice rules of the post-1989 framework, apart from defining the position of national minorities, can be understood as a multi-party, democratic, parliamentary system with partial decentralization in place. As such, in the case of the compulsory pre-school education described above, the constitutional-choice rules define that such a rule or law needs to be passed in a parliament and determines which institutional structures or individuals can make such legislative proposal, e.g., government ministers or parliament.

Secondly, Ostrom defines “collective-choice rules” as the rules “that are used in making policies” (1990, 52), thus decision-making mechanisms through which the policies are made. In the period from 1968–1969 to 1989, the collective choice-rules were stable with the Government Committee for Addressing the Question of Gypsy Population responsible for the policy design, which had to be approved by the government in accordance with the party line, as shown by the archival document. That is not to say that there was no element of collective decision-making, even during the normalization period. For instance, Lužica (Reference Lužica2016, 44) describes how in 1985, the Ministry of Finance did not approve the proposal to increase the budget recommended by the committee. In comparison, the collective-choice rules after 1989 in terms of the policymaking vis-à-vis Roma, or national minorities more generally, were continuously changing based on the results of almost every national election and the given political settlement, which was being adjusted even during electoral terms. This has had an impact on the position of the Plenipotentiary for Roma Communities and the institutional structure responsible for the agenda of national minorities, as well as the political leverage the concrete representatives holding these offices had in given political settings. This arguably provides an explanation why the law was proposed by the three coalition parliamentarians and not the Ministry of Education. In this regard, an official from the Office of the Plenipotentiary for Roma Communities highlighted in an interview that “the introduction of a compulsory pre-school education… happened only after the change of Prime Minister (in 2018),” when the Plenipotentiary Ábel Ravasz had an “unprecedented” position (Anonymous official from the Office of the Plenipotentiary for Roma Communities 2020).

Thirdly, Ostrom defines “operational rules” as those that “directly affect the day-to-day decisions” (1990, 52), therefore referring to implementation mechanisms. The pre-1989 framework was characteristic of top-down hierarchical structures and mechanisms through which the policy was implemented, as described above based on the archival documents and secondary literature (Lužica Reference Lužica2016; Jurová 2003). On the other hand, the implementation in the post-1989 framework has been pursued in a decentralized manner, and by the municipalities and civil society organizations in particular. However, such model was pursued without sufficient financial provision due to project-based financing through various funding mechanisms, predominantly the EU structural funds in recent years. The above-described case of the mayor implementing the collective-choice rule of the compulsory pre-school education, facing obstacles by the boundaries of decision-making in the financial committee, clearly demonstrates his position and boundaries within the operational-choice rules on the municipal level. This equally applies to the relevant financing mechanisms. The construction of the kindergarten facility was funded by the EU structural funds, which constitute the dominant source of funding in this area. The drafting of such a project proposal, as well as applying, implementing, and accounting for the project, if successful, constitute administratively burdensome processes. As the majority of interviews highlighted, this is especially the case for small municipalities and civil society actors who possess limited human or financial resources and who potentially have expertise in such matters. One of the interviewees suggested that because of these limitations, many municipalities or civil society actors turn to other private sources of funding. Additionally, another interviewee stressed that the funding calls often do not reflect the needs of given localities, but the municipalities still apply, even if not in need of the funding call’s focus. The reason for this is that those funds represent the main possibility of receiving extra support, as summarized by one of the interviewees, a Former Plenipotentiary for Roma Communities Miroslav Pollák:

one day we do a call for national project on field social work, then another one on access to a drinking water, a well, and then on civil patrols, and then after half a year on a social enterprise to build roads and pavements, and then on dual education in a neighboring village so that the children may do something (enter the job market) after they complete the primary school. We squeeze in those 7 years I do not know how many projects and calls, but the end result we see after the programming period is over is that nothing had been done.” (Pollák Reference Pollák2020)

Furthermore, the interviewees agreed that the EU funding continues to be assessed based on spending rather than impact. This shows that the project-based system of financing as a form of collective-choice rules significantly limits the operational-choice rules the local actors have for addressing their needs and a successful implementation of an intended policy, without any monitoring in place.

VII Conclusion