Introduction

Past prognoses regarding the imminent collapse of the nation, both as a form of group identity and as a source of political legitimacy, have proven to be untenable in the modern context (Anderson Reference Anderson2006; Triandafyllidou Reference Triandafyllidou1998). Both before and after the epochal dissipation of modernity, the Mediterranean region, characterized by its national and ethnic diversity, has been the host of multiple shifts in group boundaries and political processes of identification (Boissevain Reference Boissevain2013). Political leaders in divided Mediterranean polities, ranging from Turkey (Sarigil Reference Sarigil2010) to Israel (Will Reference Will2007), have frequently propagated and reinterpreted historico-political projects that delimit the characteristics of who belongs as a member of a given ethno-national group and who may be excluded from it (Mac Ginty Reference Mac Ginty2017, 8). The linguistic toolkits of contemporary elites in the Mediterranean region exhibit the trappings of boundary (re)shaping; President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s current exclusivist efforts to define the nativist perimeter of Turkish ethno-national identity are a contemporary, prominent example (Yavuz and Ozturk Reference Yavuz and Ozturk2020).

As a window into these processes, this study undertakes a historical interpretative analysis of the discourse of Greek-Cypriot political elites during the Cypriot Civil War of 1963–1967Footnote 1. The analysis examines how these elites framed ethno-national identity during the conflict in order to test whether the few existing historical interpretations (Loizides Reference Loizides2007; Mavratsas Reference Mavratsas1999), compared to a universalist theoretical perspective (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008), are consistent with these elites’ boundary-making strategies.

Situated in the eastern Mediterranean, Cyprus – the subject of the present case study – has remained divided along ethno-national lines for a significant portion of its modern history (Anagiotos Reference Anagiotos2016). The mid-20th century Cypriot Civil War (Varnava Reference Varnava2013) and the subsequent Turkish invasion and partition of the island in 1974 (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2007) have led to the formation of psychological wounds amongst members of the separated Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot ethnic groups that time has yet to “heal” (Bryant Reference Bryant2012). It is such scarring wounds and the seemingly perpetual partition that emphasize the particular social significance of understanding the processes of boundary-making in Cyprus.

Against this societal backdrop, Loizides (Reference Loizides2007) acknowledged how “[i]dentity formation has been historically central to… intellectual thinking in the island [of Cyprus]” (173), and set out to contribute a longue durée account of the development of Cypriot nationalism(s) and ethno-national identity. In spite of the evident merit in providing a concise summary of the competing ethno-nationalist ideological currents that have often been utilized by Cypriot political elites to mobilize the two ethnic groups, Loizides’ (Reference Loizides2007) analysis exemplifies a broader gap that exists in the literature regarding identity construction in Cyprus. In conducting macro-historical analyses (Loizides Reference Loizides2007; Mavratsas Reference Mavratsas1999; Papadakis Reference Papadakis1998), scholars have often neglected to mention or probe the Cypriot Civil War, which bore consequences that are still present in the contemporary context (Varnava Reference Varnava2013). Heeding Varnava’s (Reference Varnava2013) calls for further historical research about the understudied Cypriot Civil War, this study aims to examine the discursive framing strategies of the foremost Greek-Cypriot political elite figures who assumed the de-facto control of the Republic of Cyprus and the majority of Cypriot territory (Dodd Reference Dodd2010, 71), throughout the conflict (1963–1967).

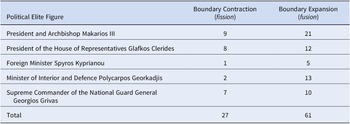

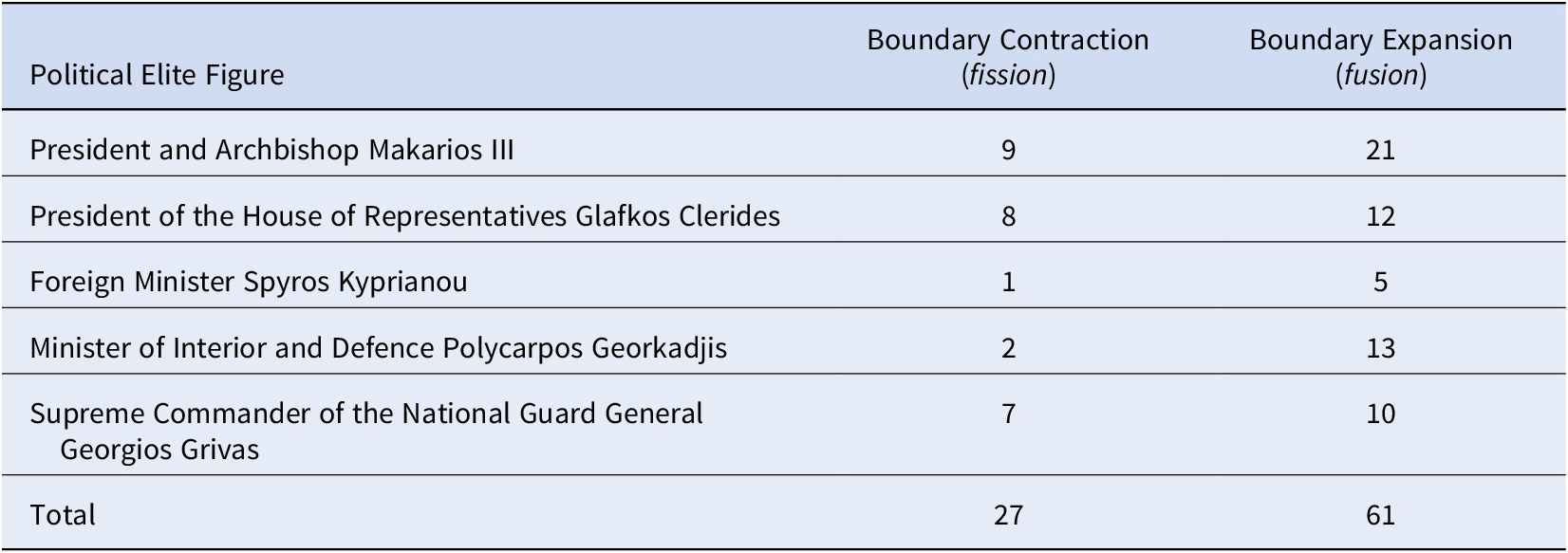

By examining a sample of primary textual sources (N = 25) regarding the discursive framing strategies of President and Archbishop Makarios III, President of the House of Representatives Glafkos Clerides, Foreign Minister Spyros Kyprianou, Minister of Interior and Defense Polycarpos Georkadjis, and General Georgios Grivas, the analysis finds that, contrary to historically informed expectations, boundary expansion is more prevalent than boundary contraction (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008). In essence, during the Cypriot Civil War, Greek-Cypriot political elites attempted to frame and mutually distinguish Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot ethno-national identity through an inclusive process of “fusion” (Wimmer, Reference Wimmer2008, 1044) that was primarily evinced by Greek nationalist (Figure 1) ideological indications.

Figure 1. The Ideological Spectrum of Group Identification

Note. Theoretical layout adapted from Loizides (Reference Loizides2007), Mavratsas (Reference Mavratsas1999), and Papadakis (Reference Papadakis1998).

This study makes two main contributions. First, by testing the contextual relevance of Wimmer’s (Reference Wimmer2008) typology, it confirms the analytical pertinence of this universalist perspective on the discursive framing of ethno-national identity for case-specific research that aims to probe ethno-national boundary-making. The findings, therefore, provide a foundation upon which future studies can analyze and even compare the framing strategies of elites in divided Mediterranean polities. Second, through its discourse-based interpretation of the relatively unexplored Cypriot Civil War, this study also aids in providing a clearer understanding of the historical processes of ethno-nationalism in Cyprus. Citizens – on both sides of the divide – maintain antagonistic narratives of the events that transpired during that period, blaming only the other side (Bryant Reference Bryant2012; Varnava Reference Varnava2013). In this regard, a better understanding of the process and strategies of ethno-national boundary-making may help to prevent the further perpetuation of divisive politics on the partitioned island.

Reflections on Ethno-National Identity: A Conceptual and Theoretical Synopsis

In academia, the two decades that preceded the turn of the 21st century saw an increasing connection between studies about national formations, which were primarily concerned with nationalism and national identity, and the examination of ethnic groups and ethnicity (Smith Reference Smith1992, 1). This interconnectedness, which was arguably influenced by the 20th-century proliferation of nation-building projects (Smith Reference Smith1992) and of civil wars that – inter alia – revolved around ethnic identification and nationalist ideologies (Kaufman Reference Kaufman, Williams and McDonald2018, 381), has produced a wealth of studies that analyze the notion of identity in conflict-torn and ethnically divided societies (Gates Reference Gates2013; Huszka Reference Huszka2014; Zambakari Reference Zambakari2015).

Despite this interdisciplinary bridge, as a branch of knowledge, the study of ethnicity is compounded by subdisciplinary and disciplinary fractionalization that hinders efforts at developing comparative practices outside the field (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008, 1026). By proposing a purportedly universally applicable and integrative typology of ethnic boundary-making strategies, Wimmer (Reference Wimmer2008) sought to ameliorate the lack of contact between “…those who study nationalism in the west and those who are interested in ethnic conflict in the south” (1026). From this perspective, Wimmer’s (Reference Wimmer2008) inherently constructivist approach, which can be set apart from the primordialist-instrumentalist axis that often guides academic debates about the nature of ethnic and national formations (Kaufman Reference Kaufman, Williams and McDonald2018; Song Reference Song2014), provides a theoretically worthwhile avenue to pursue in light of examining ethno-national identity.

Over the years, debates regarding the formation and mobilization of ethnic groups and ethno-national identity have revolved around the dividing line that stands between psychological interpretations and rational choice accounts (Kaufman Reference Kaufman2001, 17). Among these distinct – but to some degree reconcilable (Kaufman Reference Kaufman2001, 24) – schools of thought, two specific theoretical perspectives have traditionally captured the attention of scholars: primordialism and instrumentalism (Anagiotos Reference Anagiotos2016; Kaufman Reference Kaufman, Williams and McDonald2018). This section aims to point out the limitations of applying these core theoretical perspectives for the express purpose of providing an answer to the guiding research question, before turning to the academic status quo to introduce the theoretical concepts that will aid in explaining ethno-nationalism in the Cypriot context (Loizides Reference Loizides2007; Mavratsas Reference Mavratsas1999). Consequently, the theoretical framework will indicate how this study will, instead, supplement the social constructivist approach (Anderson Reference Anderson2006; Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm, Hobsbawm and Ranger2012) with the typology of ethnic boundary-making (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008) to explain the strategies through which Greek-Cypriot political elites sought to frame ethno-national identity.

Prior to the theoretical discussion, a conceptual definition of framing is due; by adapting Huszka’s (Reference Huszka2014) formulation, in this context framing indicates the manifold – and at times even conflicting – discursive practices that political elites can pursue to mobilize a given population and to construct inclusive or exclusive frames that citizens may identify with (159). In examining the Cypriot Civil War, this study will focus on the inclusive and exclusive discursive framing strategies (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008) that were utilized by Greek-Cypriot elites to set the limits of collective ethno-national identity (Nagel Reference Nagel1994, 163), by way of demarcating the boundaries of Turkish-Cypriot, Greek-Cypriot, or even of broader Cypriot group identity on the basis of three ideological currents; namely, “motherland nationalism,” “Greek-Cypriotism,” and “Cypriotism” (Loizides Reference Loizides2007, 172).

The Primordialist-Instrumentalist Axis

The primordialist perspective, which situates itself within the diverse category of psychological theories of ethnicity, builds on the primary assumption that group identity is an ascriptive and, by implication, a relatively immutable characteristic that is genealogically allocated to individuals at birth (Kaufman Reference Kaufman2001, 23). In turn, the different cultural components of the group identity of individuals, such as religious affiliation or native language, inform their perceptions of the surrounding environment, and how they are viewed by the broader society (Kaufman Reference Kaufman2001, 23). From this angle, the nation – and identification with it – is an ageless and integral aspect of the universal human experience that has endured throughout the centuries (Varnava Reference Varnava2009, 22). Clifford Geertz, one of the most consequential anthropologists of the 20th century (Yengoyan Reference Yengoyan2009), and the originating figure of the primordial camp (Kaufman Reference Kaufman2001, 24), stressed the given nature of ethnic and national identification (Anagiotos Reference Anagiotos2016, 35). According to Geertz’s (Reference Geertz1973) observation, “[b]y a primordial attachment is meant one that stems from the ‘givens’ – or more precisely, as culture is inevitably involved [emphasis added] in such matters, the assumed ‘givens’ – of social existence…” (259). Here, Geertz (Reference Geertz1973) underscores the role of culture in determining the primordial identity of individuals and challenges the often-held assumption that primordialists view ethno-national identification as a genetically delimited characteristic (Kaufman Reference Kaufman2001, 24).

Despite this caveat, the primordialist position is limited in several respects that hinder its applicability in the context of this study. First, by suggesting that mobilization around ethnic and national identities and, as a result, ethnic conflicts are outcomes of “ancient hatreds” that one can linearly trace throughout the centuries (Kaufman Reference Kaufman, Williams and McDonald2018, 382), primordialists overlook how the familial and historical links that bind ethnic groups are often the product of, elite, top-down invention, and how, for the most part, ethno-national identities are recent products of modernity (Kaufman Reference Kaufman2001, 23). Second, upon revealing the conceptual disarray that is associated with the primordialist position and the fact that few scholars claim explicit support for this position, scholars such as Coakley (Reference Coakley2018) justifiably argue that primordialism is more useful if it is understood as a constituent element of nationalism instead of a theoretical explanation of the phenomenon (328). In a related manner, Loizides (Reference Loizides2007) associates primordialism with the postulated ethno-nationalist connection that Turkish-Cypriots and Greek-Cypriots have diachronically maintained with their respective “motherlands” (173), and Anagiotos (Reference Anagiotos2016) cites primordialism as a characterization of the antagonistic manners in which individuals belonging to the two ethnic groups perceived each other in the period from 1963 to 1974 (37). Without acknowledging the notable limitations that are associated with the primordialist viewpoint, the majority of Cypriot academicians who study the divided island seem to unquestioningly hold such a perspective, which, as Varnava (Reference Varnava2020) argues, may be an outcome of their schooling in a “hyper-nationalistic” environment that is pervasive in Cyprus’ educational institutions (6).

In contrast to the relative “givenness” (Geertz Reference Geertz1973, 259) and objectivity of group identification that is assumed by primordialist accounts (Coakley Reference Coakley2018), instrumentalists structure their argument on the fundamental premise that ethnic and national identity is a fluid and subjective phenomenon (Anagiotos Reference Anagiotos2016; Hardin Reference Hardin1995; Kaufman Reference Kaufman, Williams and McDonald2018). Being a theoretical perspective that presupposes the rationality of social actors, instrumentalism perceives ethno-national identity as a repertoire of classificatory and linguistic characteristics that individuals may self-interestedly seek to associate themselves with, and – most notably – as a resource that elites can employ to mobilize groups for the objective of pursuing their political ends (Kaufman Reference Kaufman2001, Reference Kaufman, Williams and McDonald2018). As Hardin (Reference Hardin1995) plainly explains: “Leaders who want the masses behind them may provoke ethnic or nationalist sentiments” (64) – even though they may hold material personal interests instead of collective interests (Hempel Reference Hempel2004). In this regard, rather than attributing clashes between ethnic groups to “ancient hatreds,” ethnic conflict is principally comprehended as a result of the self-seeking actions of elite leadership figures that aim to maximize their power and influence (Kaufman Reference Kaufman, Williams and McDonald2018, 382–383).

What connects instrumentalist and social constructivist accounts, and distinguishes them from primordialism, is the common assumption that group identity is malleable and subject to change (Anagiotos Reference Anagiotos2016; Sambanis and Shayo Reference Sambanis and Shayo2013). While this understanding has come to form the basis of a broad consensus in the study of ethno-national identity (Anagiotos Reference Anagiotos2016; Coakley Reference Coakley2018), the fundamental fact that instrumentalism attributes identity changes to individual rational calculations rather than contextual shifts, which are the focus of constructivism (Sambanis and Shayo Reference Sambanis and Shayo2013, 299), limits the applicability of instrumentalism in relation to the analytical objectives of this study. The analysis will center around the context of the Cypriot Civil War, and how – without formulating any claims about elite rationality – this turbulent environment, along with three contextually situated ideological currents of group identification (Loizides Reference Loizides2007), informed the discursive framing of ethno-national identity, hence privileging a constructivist approach over an instrumentalist one (Hempel Reference Hempel2004, 256).

Ideologies as Spaces of Identification: The Cypriot Anatomy

In describing the dynamics of ethnic and national identity in Cyprus, Loizides (Reference Loizides2007) urges against presenting a non-exhaustive binary relationship between Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot ethno-nationalist connections with Turkey or Greece respectively (motherland nationalism), and a broader cultural and symbolic attachment to Cyprus as a whole (Cypriotism; 173). Correspondingly, although Mavratsas (Reference Mavratsas1999) speaks of an “ideological clash between Greek nationalism and Cypriotism” (92), he simultaneously attempts to provide some nuance to his argument by explaining how, rather than being mutually exclusive, such modes of identification can be conceptualized along a continuum (94).

Drawing influence from Loizides’ (Reference Loizides2007) understanding, which posits an additional ideological mode of “ethnic community identification” exemplified in Turkish-Cypriotism and Greek-Cypriotism (174), this study will examine how Greek-Cypriot political elite figures traversed the tripartite ideological spectrum of group identification (Figure 1), to inclusively and exclusively frame ethno-national identity during the 1963–1967 conflict. This spectral understanding of collective identity is supported by a multitude of studies that outline the “hybrid” and “fluctuating” nature of identification in the north or the south of the Cypriot polity (Akçalı Reference Akçalı2011; Vural and Özuyanık Reference Vural and Özuyanık2008; Vural and Rustemli Reference Vural and Rustemli2006). Take, for instance, Vural and Rustemli’s (Reference Vural and Rustemli2006) poll-based findings, which indicate that, for a number of the Turkish-Cypriot inhabitants of Northern Cyprus, ethno-national identity is not monolithically defined and tends to fluctuate among the opposing poles of a “civic” Cypriotist affiliation and an exclusivist Turkish nationalism (344). In this sense, Vural and Rustemli (Reference Vural and Rustemli2006), who argue that this diagnosis of inconstant identity is also applicable for the Greek-Cypriot ethno-national group, suggest that collective forms of identification are subject to shifts on the basis of contextual influences (343). Accordingly, for Akçalı (Reference Akçalı2011), the mutable identities that Cypriots assume are a contingent outcome of discursive and extra-discursive environmental factors, such as the economic development of a particular region (1743).

The term Greek nationalism, which for present purposes will be used interchangeably with the term motherland nationalism, indicates a postulated identification with mainland Greece and with Hellenic history and culture (Loizides Reference Loizides2007; Persianis Reference Persianis1996; Mavratsas Reference Mavratsas1999). Hence, denoting the inclusion of Greek-Cypriots in the broader umbrella of Hellenism, and the exclusion of Turkish-Cypriots and several Greek-Cypriot communists that – as an implication of this ideology – were disregarded in the mid-20th century irredentist pursuit of Enosis (political union with Greece; Loizides Reference Loizides2007; Papadakis Reference Papadakis1998).

The ideology of Greek-Cypriotism emphasizes the role of the ethnic group as the primary source of identification, and, at times, draws both from the repertoire of motherland nationalism and Cypriotism (Loizides Reference Loizides2007, 181). Although, here for descriptive purposes, it is situated in the middle of the spectrum; historically, Greek-Cypriotism has served a two-pronged exclusionary function by privileging Greek-Cypriot ethno-national objectives over those of the broader Cypriot and Greek polities (Loizides Reference Loizides2007, 183).

Distinctively, Cypriotism – which exhibits a spirit of rapprochement between Turkish-Cypriots and Greek-Cypriots and highlights the development of a collective Cypriot patriotic identity – acts as an inclusive source of identification that, unlike Greek nationalism and Greek-Cypriotism, does not explicitly distinguish along ethno-national lines (Loizides Reference Loizides2007, 178). In effect, this Cypriotist form of identification rests on a “civic” perception of the nation (patrída) that emphasizes a cross-ethnic attachment to Cyprus as a territorially defined political space (Vural and Rustemli Reference Vural and Rustemli2006, 344–345) and unites the Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot ethno-national groups by blurring the cultural boundaries that divide them (Şahin Reference Şahin2011, 591).

Theoretical Framework: The Constructivist Topography of Boundary-Making

A necessary step before the employment of the three above ideologies as explanatory tools for the discursive practices of Greek-Cypriot elites is their integration in the theoretical paradigm of constructivism (Motyl Reference Motyl2010) and the related typology of ethnic boundary-making (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008). The social constructivist approach – which guides this study – builds on the fundamental assumption that the essence of ethno-national identity is a collection of imagined and manufactured ideas, for instance, conventions regarding which people ought to be excluded or included in social groups (Kaufman Reference Kaufman2001, 23). In agreeing with Varnava’s (Reference Varnava2009) apt statement that “identity is predicated upon perceptions not facts,” identification with a given ethno-national group will be seen as a matter of political imagination rather than an objective reality in the context of this investigation (23). Such an understanding is evident in Anderson’s (Reference Anderson2006) influential conceptualization of the nation as an “imagined political community” (6) and in Hobsbawm’s (Reference Hobsbawm, Hobsbawm and Ranger2012) characterization of national formations as “all-embracing pseudo-communities” (10).

By discarding the primordialist assumption regarding the fixity of ethnic and national configurations and the interest-based explanations that are propounded by instrumentalist perspectives (Song Reference Song2014, 829), Wimmer (Reference Wimmer2008), who in his writing utilizes the notion of imagined communities (1033), proposes an understanding of ethnicity through the inherently constructivist processes of “constituting and re-configuring groups by defining the boundaries between them” (1027). Most relevantly, Wimmer’s (Reference Wimmer2008) ethnic boundary-making approach distinguishes between two strategies of “boundary shifting”: expansion and contraction (1031).

Boundary expansion, which is a typically inclusive strategy, signals an effort to widen ethnic boundaries and to decrease existing types of identification through the process of “fusion” (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008, 1031). In the Cypriot Civil War context, fusion will be indicated through the nation-building patriotic ideology of Cypriotism which amalgamates the Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot ethno-national identities into a unitary Cypriot one, and Greek nationalism which de-emphasizes the distinctive nature of Greek-Cypriot ethno-national identity and subsumes it under a relatively all-encompassing Greek identity (Loizides Reference Loizides2007; Mavratsas Reference Mavratsas1999; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008). In contrast, the exclusive strategy of boundary contraction signifies the pursuit of more limiting patterns of identification by enacting the process of “fission,” which forms a dichotomy in available categories or emphasizes “lower levels” of distinction between given groups (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008, 1036). The ideology of Greek-Cypriotism will serve as the primary indication of fission, as it differentiates Greek-Cypriot ethno-national identity from the broader Cypriot patriotic identification that would also include citizens that identify as Turkish-Cypriot, and bisects Greek identity and Greek-Cypriot identity according to cultural distinctions (Loizides Reference Loizides2007; Mavratsas Reference Mavratsas1999; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008). Moreover, the ideology of Greek nationalism – at certain instances – may indirectly indicate a lower-level exclusion of Turkish-Cypriots and Greek-Cypriot communists through the pursuit of Enosis, although it must be noted that, in their mid-20th century mobilizational discourse, Greek-Cypriot political elites generally asserted their “dream of the union” with Greece, rather than an explicit exclusion of those that the “dream” did not account for (Loizides Reference Loizides2007, 176).

According to the available historical interpretations, President and Archbishop Makarios III and the majority of Greek-Cypriot political elites that presided over the post-independence government of the Republic of Cyprus are predominantly associated with the ideological orientation of Greek-Cypriotism over Greek nationalism (Loizides Reference Loizides2007, 182-183), with scholars such as Mavratsas (Reference Mavratsas1999) adding that a commitment to a broader Cypriot identification was effectively non-existent in the period from 1960 to 1974 (96). Thus, due to the ideological predominance of the innately exclusive ideology of Greek-Cypriotism, one could expect that, during the Cypriot Civil War, Greek-Cypriot political elites would primarily frame ethno-national identity through the exclusivist strategy of boundary contraction rather than boundary expansion while aiming to define the limits of collective ethno-national identity. The guiding hypothesis is therefore:

H1 = Boundary contraction is more prevalent than boundary expansion in the discursive framing strategies of Greek-Cypriot elites during the Cypriot Civil War.

The analysis examines the relative prevalence of boundary contraction and expansion for two reasons. First, due to the interpretative and highly reflexive character of discourse analysis (Halperin and Heath Reference Halperin and Heath2016, 356–357), the introduction of a measure of prevalence sets the ground for systematic inspection of the sample of textual sources that will indicate the discourse of Greek-Cypriot political elites, rather than gathering evidentiary support through mere conjecture – something that has marred the appearance of discourse analysis in the eyes of several scholars and has led to critique regarding its supposedly non-empirical nature (Milliken Reference Milliken1999, 227). Second, in his proposal for future research, Wimmer (Reference Wimmer2008) suggests how subsequent analyses could pay attention to the contexts in which a given strategy of ethnic boundary-making gains more frequency or salience (1026). By focusing on the relative prevalence – a proxy of salience – of boundary expansion and contraction in the context of the Cypriot Civil War, this study aims to follow and expand upon Wimmer’s (Reference Wimmer2008) suggestion.

Several types of evidence could falsify the guiding hypothesis (H1). If the discursive practices of Greek-Cypriot political elites indicate that neither boundary contraction nor boundary expansion is more prevalent than the other – perhaps because such concepts are not directly applicable to the Cypriot Civil War context – or if, conversely, boundary expansion is more prevalent as a discursive framing strategy, then there will be evidentiary ground to reject the hypothesis. Further, the methodology of discourse analysis allows for the induction of possible contextually specific patterns of meaning (Halperin and Heath Reference Halperin and Heath2016, 356). As such, if upon examination of the textual sources a previously non-hypothesized discursive framing strategy emerges, which proves to be more prevalent than contraction and expansion, then the hypothesis will be falsified, hence forming the basis for a distinct process of theorization regarding the framing of ethno-national identity in Greek-Cypriot political elite discourse.

Methodology: The Pillars of a Discursive Exploration

Overall, discourse-analytical approaches share the constructivist ontological assumption that social realities – like ethno-national identity – are often products of social construction (Halperin and Heath Reference Halperin and Heath2016, 536), with specific approaches such as Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) stressing the role of discourse in transmitting ideology and framing identities (Cameron and Panović Reference Cameron and Panović2014, 2). In the present case, this study will employ a variant of the CDA school, the Discourse Historical Approach (DHA), which enables the development of a systematic examination of the abovementioned hypothesis (Wodak Reference Wodak, Wodak and Meyer2001). The analytical employment of the methodology of DHA is, in Şahin’s (Reference Şahin2011) viewpoint, congruent with the notion that ethno-nationalist modes of identification are delineated and activated by discursive utterances (585).

As a method of analysis, DHA provides three stages that are necessary for the empirical study of textual sources (Aydın-Düzgit Reference Aydın-Düzgit2016; Wodak Reference Wodak, Wodak and Meyer2001). At a primary stage, the core “discourse topics” are identified (Aydın-Düzgit Reference Aydın-Düzgit2016, 48). In observing the context of the Cypriot Civil War, I have selected the relevant topics on account of their linkage with the ideological spectrum of group identification (Figure 1), which – as indicated previously – has been theoretically integrated with the strategies of boundary expansion and contraction. Accordingly, the analysis of Greek-Cypriot political elite discourse will center on the following central topics: The historical legacy of EOKA (National Organization of Cypriot fighters), the Greek-Cypriot political elite perceptions of the civil war clashes between Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot armed groups, and, lastly, the role of Cypriot sovereignty (Dodd Reference Dodd2010; Loizides Reference Loizides2007). The first topic relates to Greek nationalism due to EOKA’s dual “struggle” for Enosis and independence from British colonial rule (1955–1959) that often relied on the symbolism of Greek history and culture (Loizides Reference Loizides2007, 175). The second topic is linked with the ethno-nationalist current of Greek-Cypriotism due to its perceivable ideological predominance in the “Makarios establishment” (Loizides Reference Loizides2007, 183), which governed the Republic of Cyprus during the Cypriot Civil War (Dodd Reference Dodd2010, 71). Lastly, the third topic is connected with the ideology of Cypriotism that aims to foster a mutual Cypriot patriotic allegiance in a bi-communalFootnote 2 and – by implication – sovereign Cypriot federal state (Ramm Reference Ramm2006, 526). In sum, each discourse topic bears considerable historico-political relevance for the 1963–1967 conflict (Dodd Reference Dodd2010; Loizides Reference Loizides2007; Ramm Reference Ramm2006) and, as such, is likely to be directly or indirectly present in the rhetoric of Greek-Cypriot elites regarding the ethno-national identity of the Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot inhabitants of Cyprus.

After the discourse topics are determined, the subsequent stage of DHA requires an investigation of the “discursive strategies” that are utilized for the framing of identity, which, in the context of this study, will be conducted by probing the textual sources with a set of analytical questions (Aydın-Düzgit Reference Aydın-Düzgit2016; Reisigl and Wodak Reference Reisigl and Wodak2001). Based on the ethnic boundary-making lens, what are the recurring inclusive and exclusive frames of Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot collective ethno-national identity? What are the contextually specific metaphors, symbols, and characterizations (e.g., Tourkóplikti Footnote 3 ) that are deployed to define Turkish-Cypriots, Greek-Cypriots, or the Cypriot polity as a whole? How, if at all, are the ideological components of Greek nationalism, Greek-Cypriotism, and Cypriotism explicitly conveyed in the texts? By employing these questions to examine the textual material under consideration, I will construct my discussion of the abovementioned discourse topics, and I will test the guiding hypothesis (H1) of this discursive investigation.

Consequently, the final stage of DHA focuses on the “linguistic means” that are implemented in connection with the relevant discursive framing strategies (Aydın-Düzgit Reference Aydın-Düzgit2016; Wodak Reference Wodak, Wodak and Meyer2001). In the analysis section, I will set forth the unearthed linguistic means through a collection of excerpts that represent patterns between the discursive framing strategies of Greek-Cypriot political elites and relate explicitly or tacitly to the three central discourse topics (Aydın-Düzgit Reference Aydın-Düzgit2016, 49). Effectively, each linguistic mean, which will be represented as a rhetorical excerpt in the discussion, acts as a single evidentiary manifestation of either the strategy of boundary expansion or contraction.

Greek-Cypriot Political Elites and Textual Sources

The selection of the pertinent sample of foremost Greek-Cypriot political elite figures is grounded in Winters’ (Reference Winters2011) theorization regarding elite-controlled power resources, which signify “particular capacities, instruments, or positions that individuals hold in varying concentrations or magnitudes and use for social and political influence” (12). In essence, the five individuals who will aid in constructing an image of Greek-Cypriot political elite discourse all fulfil the “official positions” criterion of power resources, and in certain cases also yielded the ability to form political networks and to rally support for political causes (e.g., Enosis) through their “mobilizational power” (Winters Reference Winters2011, 12–15). These individuals and their terms in power are as follows: President (1960–1974) and Archbishop (1950–1977) Makarios III; President of the House of Representatives (1960–1976) Glafkos Clerides; Foreign Minister (1960–1972) Spyros Kyprianou; Minister of Interior (1960–1968) and Defense (1964–1968) Polycarpos Georkadjis; Supreme Commander of the National Guard of Cyprus (1964–1967) General Georgios Grivas (Dodd Reference Dodd2010; Hadjipolycarpou Reference Hadjipolycarpou2015; Kıralp Reference Kıralp2017; Schemmel Reference Schemmel2020). Besides the fact they held different positions in the Republic of Cyprus, three out of five of the selected political elites (excluding Spyros Kyprianou and Makarios III, whose political participation in the Enosis “struggle” was indirect as he was the spiritual leader of the armed resistance; Novo Reference Novo2013) were all former high-ranking members of EOKA (Holland Reference Holland1998). The involvement of Clerides, Georkadjis, and Grivas in EOKA’s guerrilla campaign and their subsequent assumption of office in the Republic of Cyprus evidences what Varnava (Reference Varnava2021) deems as the process of “Eokatisation” that affected the post-independence Greek-Cypriot polity, which saw the extensive participation and primacy of ex-EOKA members in the Makarios administration (87).

The primary textual sources that I will employ to examine the discourse of the above Greek-Cypriot political elites have been retrieved from the press releases archival database (https://www.piopressreleases.com.cy/) of the Republic of Cyprus’ Press and Information OfficeFootnote 4 (PIO). Following the restriction of the search scope to only account for documents that were produced in the period from 1963 to 1967, I entered 10 keywords that refer to the central discourse topics and to the names of the 5 Greek-Cypriot elites to locate the sources in the database (see Supplementary Appendix). Upon inspection of the entirety of the relevant search results, I delineated an initial population of 75 official statements and speeches on the grounds of their publicity (Aydın-Düzgit Reference Aydın-Düzgit2016; Cameron and Panović Reference Cameron and Panović2014) – for instance, if they were public commemorative addresses (Wodak, de Cillia, Reisigl, and Liebhart Reference Wodak, de Cilia, Reisigl and Liebhart2009, 70) in the case of the EOKA discourse topic – and because the descriptive title of these sources directly indicated that they included the discourse of either 1 of the 5 Greek-Cypriot political elites. To minimize the possibility of selection bias, every third textual source that corresponds to each keyword has been chosen for analysis out of the initial population (Halperin and Heath Reference Halperin and Heath2016, 175), thus reducing the final sample down to 25 sources. According to the ethnic boundary-making approach, the coding of the relative prevalence of boundary expansion and contraction in the discursive framing strategies of Greek-Cypriot elites will be conducted through a set of discursive indicators exemplified in Greek nationalism, Greek-Cypriotism, and Cypriotism (see Supplementary Appendix Table A1). These discursive indicators, which were also retrieved from the archival database (Press and Information Office [PIO] 1964a 1965a 1966e 1967c), are examples of how the processes of boundary-making fusion and fission can be demonstrated through the ideologies of Greek nationalism, Greek-Cypriotism, and Cypriotism in the rhetoric of Greek-Cypriot elites. For the purpose of replicability, each indicator that guides the coding criteria of the analysis is available in the Supplementary Appendix, and, accordingly, future researchers of the Cypriot Civil War could reproduce the findings of this study by utilizing these criteria to probe the 25 textual sources (see References: PIO 1963a-1967e; excl. 1964a 1965a 1966e and 1967c) for the relative prevalence of the strategies of boundary expansion and contraction.

Historical Context: Religion and the Ethnos

In 1571, Cyprus came under the dominion of the Ottoman empire, which according to the millet structure, distinguished imperial subjects by their affiliation to “semi-autonomous” religious groups (Constantinou Reference Constantinou2007, 254). As a result, up to the arrival of British colonial rule in 1878, the most salient differentiation among the group identity of individuals in Cyprus hinged on the distinction between Muslim or Orthodox Christian religious affiliation; although it must be noted that during the Ottoman period, in a syncretistic fashion, several individuals also blended and trespassed the boundaries of religious group identity (Constantinou Reference Constantinou2007, 255–256). Importantly, the demarcation of Ottoman imperial subjects that was informed by their religiosity did not prevent the culturally integrated Cypriot Muslims and Christians – who were affected by joint socio-economic adversities (Vural and Rustemli Reference Vural and Rustemli2006) – from partaking in common traditions and acts of interfaith marriage (Varnava Reference Varnava2009, 155). Notwithstanding the notable integration of the differentiated Orthodox Christian and Muslim communities, the Ottoman domination of Cyprus led to the formation of “class/social cleavages” between rural and urban areas that also influenced interreligious contacts and lasted even until the early years of British rule in the island (Varnava Reference Varnava2017, 31).

The effort of the British colonial administration to “modernize” the millet structure in Cyprus saw a gradual top-down process of ethnicization of the preexisting religious group differentiation (Constantinou Reference Constantinou2007, 256), which influenced the reconstruction of Muslim religious identity into Turkish ethno-national identity and Christian religious identity into Greek ethno-national identity (Anagiotos Reference Anagiotos2016, 28). While implementing their view of modernity that had the effect of obstructing Ottoman-influenced integrating efforts among Muslims and Christians (Varnava Reference Varnava2009, 159), the policies of British officials initially turned individuals from both the “lower” and “higher” classes of Cyprus into “imperial citizens” and then into “Turks” or “Greeks” (Varnava Reference Varnava2020, 6–7). This modernizing process is evident from the historically contingent transformation of census classifications in the 20th-century Cypriot context (Constantinou Reference Constantinou2007, 257). Before reaching their formative period and the Cypriot peasantry in the wake of World War I, ethno-nationalist visions of Greek and Turkish motherland nationalism(s) were propounded by a number of literate elites in the two religiously defined communities (Varnava Reference Varnava2009; Reference Varnava2017). Given this, one can argue that the cultivation of the ideologically dominant Greek nationalism – alongside Turkish nationalism (Dağlı Reference Dağlı2016) – was an “elitist” phenomenon, which was enabled by the impulse of modernization that defined British colonial rule in the island (Varnava Reference Varnava2017, 34).

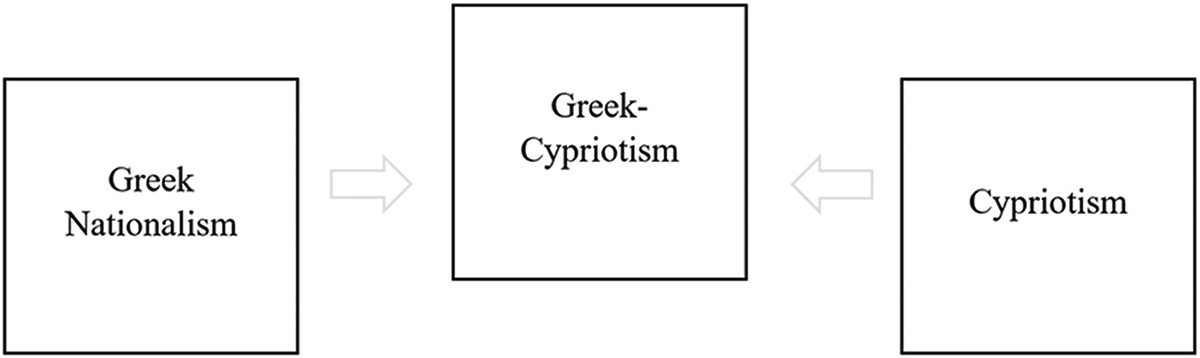

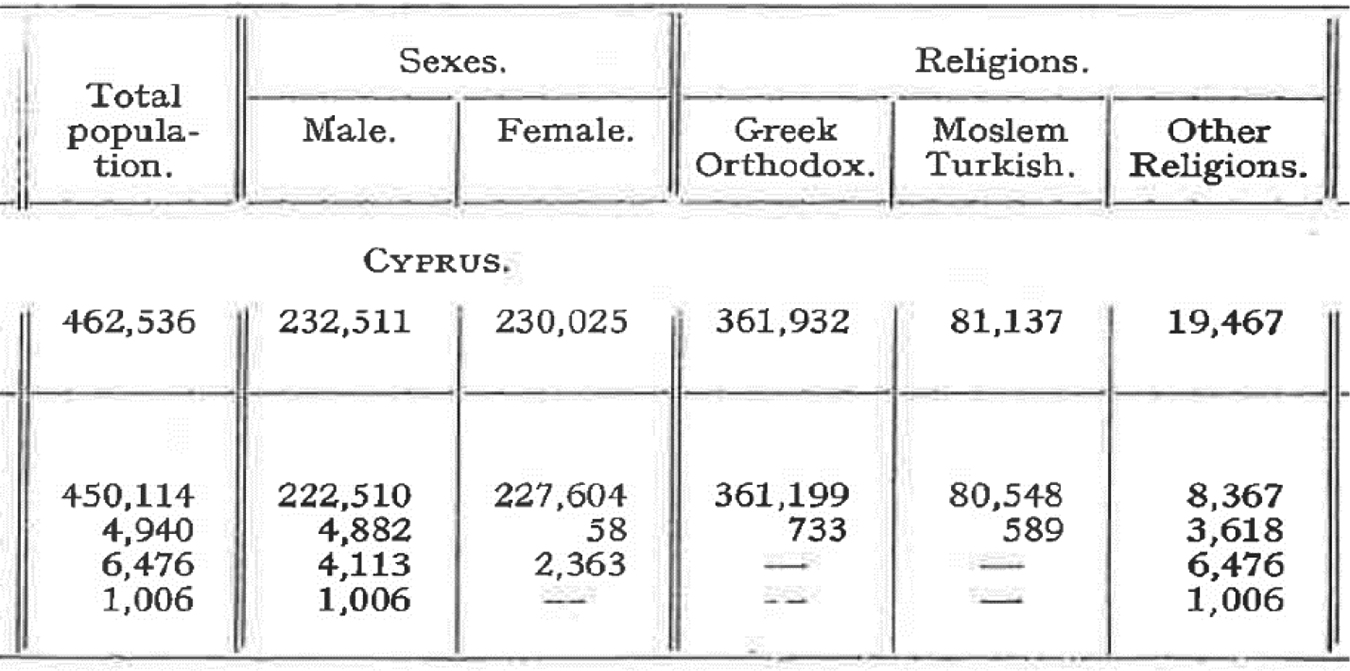

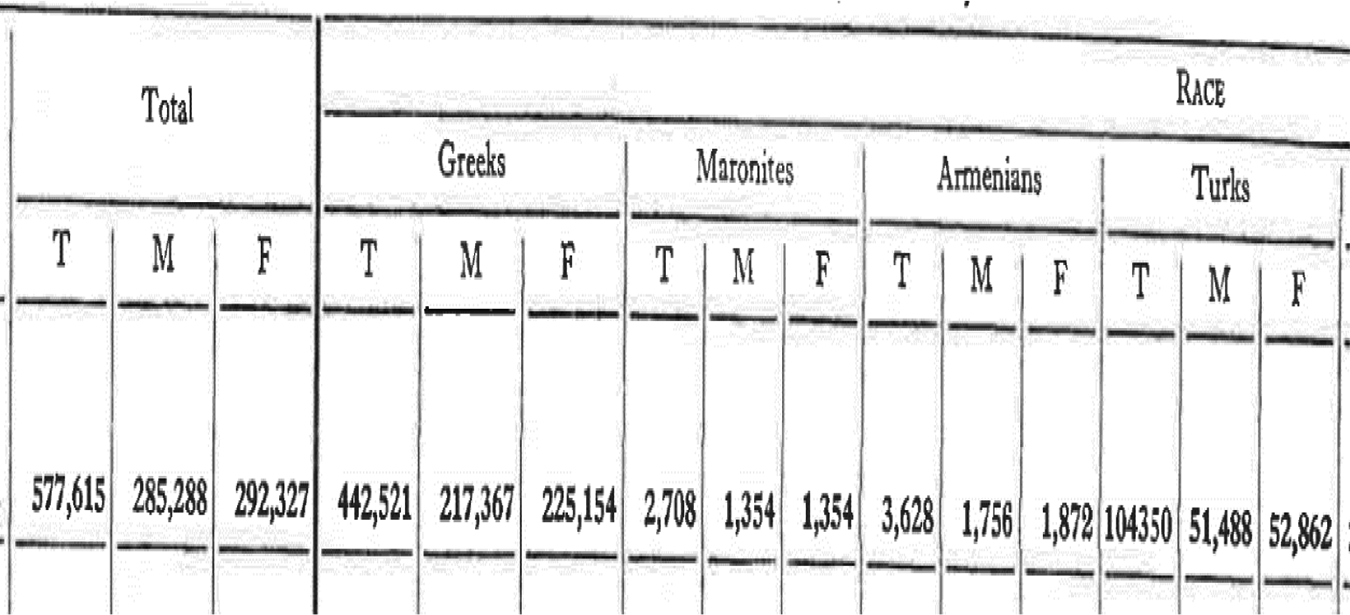

As Anderson (Reference Anderson2006) argues, throughout the development of the colonial period, religious identity was progressively phased out as a predominant source of classification in censuses and was replaced with ethnic and racial group identities (164–165). By way of illustration, in the 1946 Census of the British colonial administration of Cyprus, one can observe an ethno-religious dichotomy between “Greek Orthodox” and “Moslem Turkish” citizens (Figure 2), whereas by 1960, when the Republic of Cyprus was granted its independence (Dodd Reference Dodd2010), the dichotomy was enacted in ethno-racial terms, differentiating between “Greeks” and “Turks” (Figure 3). In effect, this shift in census-based categorizations indicates how religion was substituted as a source of identification with an ethno-national and socially constructed (Şahin Reference Şahin2011) perception of Greece and Turkey as the motherlands of individuals who, during the Ottoman era, respectively clung to their Orthodox and Muslim identities (Harmanşah Reference Harmanşah2021, 4).

Figure 2. Ethno-religious distinction between “Greek Orthodox” and “Moslem Turkish” citizens

Source: Census of Population and Agriculture 1946, by British Government of Cyprus, 1949, https://www.mof.gov.cy/mof/cystat/statistics.nsf/All/76344D539E2AF975C2257F64003CFD31/$file/POP_CEN_1946-POP(RELIGION)&HH_DIS_MUN_COM-EN-121017.pdf?OpenElement

Figure 3. Ethno-racial distinction between “Greeks” and “Turks”

Source: Census of Population and Agriculture 1960, by Republic of Cyprus, 1960, https://www.mof.gov.cy/mof/cystat/statistics.nsf/All/1240A557C7D9F399C2257F64003D0D54/$file/POP_CEN_1960-POP(RELIG_GROUP)_DIS_MUN_COM-EN-250216.pdf?OpenElement

Findings and Analysis: Contextualizing Boundary Expansion and Contraction

Contrary to the previous theorization, close inspection of the 25 textual sources reveals that boundary expansion – evidenced through Greek nationalism – is more prevalent that boundary contraction in the discursive framing strategies of Greek-Cypriot political elites during the Cypriot Civil War (Table 1), hence leading to the rejection of the guiding hypothesis (H1). As will be elaborated upon below, Greek-Cypriot political elites primarily framed Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot collective ethno-national identity in mutually distinguishable but inclusive terms through the process of fusion, which incorporated and amalgamated different types of identification (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008, 1044). To a considerable extent, Wimmer’s (Reference Wimmer2008) universalist ethnic boundary-making typology proved to be applicable to the mid-20th century discursive practices of Greek-Cypriot political elites; nevertheless, certain contextually specific utterances unveiled the difficulty that is inherent in attempts to interpret clear linguistic borders between conceptually distinct identificatory ideologies (Loizides Reference Loizides2007, 174).

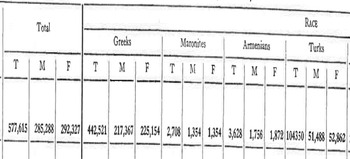

Table 1. Relative Prevalence of Inclusive and Exclusive Discursive Framing Strategies

Note. Numerical data deduced from a sample of 25 textual sources that were published by the Press and Information Office (PIO) in the period from 1963 to 1967.

“Imprisoned Graves” and EOKA’s Legacy

Following the outset of the Cypriot Civil War on December 21, 1963 (Dodd Reference Dodd2010, 51), General Georgios Grivas, the former military commander of EOKA, returned to Cyprus in 1964 to assume the leadership of the National GuardFootnote 5 (Kıralp Reference Kıralp2019, 372). Upon his arrival, Grivas – vernacularly referred to as “Dighenis” (Holland Reference Holland1998, 308) – paid a symbolic visit to the Imprisoned Graves monument located in the Central Prison of Nicosia (PIO 1964d). This monument is the place of interment of nine Greek-Cypriot EOKA combatants who were officially executed by the British colonial administration of Cyprus, three fighters who were killed “in combat,” and one individual, Stylianos Lenas, who succumbed to his wounds upon being hospitalized after a clash with British forces (PIO 2012).

In addressing the deceased combatants, Grivas expressed how their “remembrance will remain in the souls of the people as an immortal memorial, which will symbolize duty to the motherland for generations to come” (PIO 1964d, para. 5). This postulated obligation to motherland Greece that is advanced by Grivas indicates an integration of Greek-Cypriot ethno-national identity and Hellenic identity that is characteristic of the relative prevalence of boundary expansion in the discourse of Greek-Cypriot political elites. By emphasizing the “duty” to Greece that binds Greek-Cypriots, Grivas frames their collective ethno-national identity through a process of inclusion, and he simultaneously embeds the perceived martyrdom of EOKA combatants within the civil war context by stating that “whatever was achieved and will be achieved [emphasis added] is due to [their] sacrifice” (PIO 1964d, para. 5). Three days after Grivas’ visit to the Imprisoned Graves, in a public rally that was held in his honor (PIO 1964f), ex-member of EOKA (Holland Reference Holland1998) and Minister of Interior and Defence Polycarpos Georkadjis addressed the crowd with the following words:

The recalling to mind of the exploits of the Greek nation revives once more the legend of the race and enlivens the glory of the Greek Cypriots who, in 1955–1959, wrote the most recent epic in our history [emphasis added] with Dighenis as leader. (PIO 1964f, 1)

Although Georkadjis employs the term “Greek Cypriots,” which indicates a hyphenation of Cypriot and Greek identity, he subsumes EOKA’s 1955–1959 military campaign under a broader historical frame of endeavors that were purportedly undertaken by the racialized “Greek nation” (PIO 1964f, 1), thus incorporating Greek-Cypriot history and, by implication, ethno-national identity in an inclusive Hellenistic national image. Georkadjis’ discourse evokes what Bryant (Reference Bryant2004) perceives as the ethno-nationalist “thesis of continuity” (96) and what Anderson (Reference Anderson2006) describes as the “historical tradition of serial continuity” that is ingrained in “second-generation” nationalist ideologies, which were supposedly developed in the period from 1815 to 1850 (194–195). The ideology of Greek nationalism, which – contrary to Kitromilides’ (Reference Kitromilides1989) assertion – underwent its elite-driven formative period during the early to mid-20th century in Cyprus (Bryant Reference Bryant2004; Varnava Reference Varnava2009), especially after the onset of World War I (Varnava Reference Varnava2017, 32), is observably present in Georkadjis’ narrative of boundary expansion. This is evidenced by the fact that he refers to the “most recent epic” of the nation (PIO 1964f, 1) to conjure up a notion of a historical path of continuity that unites Greek-Cypriot and Greek individuals.

After Georkadjis’ initiatory address at the rally, Grivas sought to mobilize the Greek-Cypriot audience to participate in the civil war efforts by expressing that “Greece’s God, who signed her freedom in 1821, has also signed the freedom of Cyprus which he is offering to us. It is up to us to take it” (PIO 1964g, 3). In a rather theological representation that imbues an image of divine providence, Grivas engages in the notion of historical continuity as he links the Greek Revolution of 1821 that was waged against Ottoman rule (Kitromilides Reference Kitromilides1989, 179) with the effort to obtain “freedom” through the Cypriot Civil War (PIO 1964g, 3) that is placed in the hands of the Greek-Cypriots. Notably, Grivas expands the boundaries of Greek-Cypriot ethno-national identification by utilizing the divine imagery of “Greece’s God” (PIO 1964g, 3) that is postulated as being responsible over the fate of Cyprus.

On August 15, 1965, the day in the Orthodox Christian calendar that celebrates the Dormition of Mary the Theotokos (Mother of God; Khodr Reference Khodr2008, 31), President and Archbishop Makarios III gave a speech at the Chrysoroyiatissa monastery (PIO 1965e), located in Paphos (Beckingham Reference Beckingham1956). More than once, Makarios used the term “Greeks of Cyprus” to refer to Greek-Cypriots, and he proclaimed that “[i]t is for Enosis that our [Greek-Cypriot] struggles have been conducted and it is for enosis that these struggles will be carried on” (PIO 1965e, 1–2). By eliminating the hyphen in Greek-Cypriot identity to define Greek-Cypriots as Greeks, Makarios enacts a process of boundary expansion that incorporates Greek-Cypriots into a unitary Hellenic identification. Moreover, Makarios’ sentiment that previous “struggles” – primarily referring to EOKA’s campaign – were in pursuit of Enosis, and that future struggles would be “carried on” with the identical objective in mind (PIO 1965e, 2), forms an ethno-nationalist ideological link between EOKA’s past historical endeavors and the actions that were going to be conducted by Greek-Cypriots during the 1963–1967 civil war. Despite the discursive employment of Enosis having been previously theorized as a possible indication of boundary contraction, in this context, Makarios does not draw an exclusive dichotomy between the Cypriot citizens that were perceived as politically supportive of the sought-after union with Greece and those that implicitly were not (i.e., Turkish-Cypriots and Greek-Cypriot communists; Loizides Reference Loizides2007).

The “Turkish Element” and Civil War Clashes

By way of contrast with the relatively consistent pattern of boundary expansion in the language of Greek-Cypriot political elites regarding the EOKA discourse topic, while mentioning the armed clashes of the Cypriot Civil War, the five elite figures demonstrated a combination of inclusive and exclusive discursive framing strategies. This divergence between the two discourse topics could be explained by the role that different audiences play in the construction of ethno-nationalist narratives of identity (Nagel Reference Nagel1994); as Mavratsas (Reference Mavratsas1999) explains, political leaders may adapt the ideological elements of their discourse according to the audience they are addressing (96).

In referring to EOKA, Greek-Cypriot elites were perhaps more inclined to solely engage in the inclusivist ideological dimensions of Greek nationalism to appeal to the domestic Greek-Cypriot audience (Mavratsas Reference Mavratsas1999), whereas their discourse regarding the clashes of the Cypriot Civil War would possibly address a broader Cypriot or international audience, thus displaying an array of different frames of collective ethno-national identity.

While describing the military operations of the National Guard, Grivas maintained that he aimed at “peaceful co-existence with the Turkish element” and that Greek-Cypriots were “fighting to achieve [this] peaceful co-existence” (PIO 1964g, 2). Here, in an arguably paradoxical manner, Grivas purports that the clashes of the Cypriot Civil War were waged with an aim to achieve harmony between Greek-Cypriots and Turkish-Cypriots, and he simultaneously expands the boundaries of Turkish-Cypriot ethno-national identity by characterizing Turkish-Cypriots as the “Turkish element” (PIO 1964g, 2). In a similar vein to Makarios’ removal of the hyphenation of Greek-Cypriot identity, Grivas emphasizes the Turkish component of Turkish-Cypriot identification and includes Turkish-Cypriots into a unitary Turkish umbrella. This contextually specific characterization is also present in the discourse of the President of the House of Representatives Glafkos Clerides. Speaking on behalf of Greek-Cypriots, Clerides voiced a “desire to live in peace […] co-operating with the Turkish element” (PIO 1967a, 2).

Besides the fact that both Clerides and Grivas claim that they seek reconciliation with the Turkish-Cypriot ethnic group, their utilization of the “Turkish element” term (PIO 1964g 1967a) to some extent indicates a discursive objectification of Turkish-Cypriot citizens that reduces them to the status of a mere “element” in the context of the Cypriot polity, something that is generally absent in their descriptions of Greek-Cypriots. Such an indication of discursive objectification is more clearly evidenced in Makarios’ assertion that the Greek-Cypriot armed forces did not seek “to drive the Turkish minority out of Cyprus in spite of the fact that it constitutes a remnant [emphasis added] of the Ottoman conquest” (PIO 1965e, 1). In this regard, Makarios frames the Turkish-Cypriot ethnic group as an outcome of imperial rule, a remaining object-like fragment of the Ottoman dominion of Cyprus – which lasted from 1571 to 1878 (Constantinou Reference Constantinou2007; Gates Reference Gates2013) – and amalgamates Turkish-Cypriot ethno-national identity with Turkish identity by employing the symbolism of the Ottoman empire (Papadakis Reference Papadakis and Lytra2014). While the decision of Greek-Cypriot elites to cast Turkish-Cypriots as an “element” (PIO 1964g) or a “minority” (PIO 1965e) hints at a form of discursive objectification, it also points out the reluctance of elite figures to acknowledge this ethnic group as a proportionally equal political community in the consociational Republic of Cyprus. According to the 1960 Constitution of the Republic of Cyprus, the members of the Turkish-Cypriot ethnic group were meant to participate equitably with Greek-Cypriots in the governance of the island (Dağlı Reference Dağlı2016), but, in their objectifying rhetoric, Greek-Cypriot elites failed to recognize the Turkish-Cypriot communal calls for equality and “respect” (Bryant Reference Bryant2004, 174).

In conjunction with the foregoing indications of boundary expansion, Greek-Cypriot political elites enacted a dichotomizing process of contraction in their descriptions of Turkish-Cypriot ethno-national identity. As an illustration, in referring to the Turkish-Cypriot civilian casualties of the civil war clashes, Georkadjis divided the ethnic group into two mutually exclusive categories: “Turkish citizens of the Republic” which were also characterized as “innocent citizens,” and “Turkish rebels” (PIO 1963a, 2). This indirectly implies a process of disidentification that is characteristic of fission (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2008, 1036). Although Wimmer (Reference Wimmer2008) refers to internal disidentification, whereby groups reject and contract the categorizations that outside actors use to define them (1036), in this context Georkadjis engages in an externally imposed process of disidentification that contracts the boundaries of Turkish-Cypriot ethno-national identity and dissociates the “innocent” Turkish-Cypriot citizens, who are included under the jurisdiction of the Republic of Cyprus, from the “Turkish rebels” (PIO 1963a, 2). Apart from Georkadjis’ dichotomy, this dynamic of boundary contraction is observable in Clerides’ distinction between “Turkish compatriots” and “Turkish extremist leaders” (PIO 1967a, 2), in Grivas’ description of “right-thinking Turks,” which are differentiated from the Turkish-Cypriot political leadership (PIO 1964g, 2), and in Makarios’ portrayal of “Turkish terrorists,” which are normatively distinguished from the Turkish-Cypriot citizens who populated the ethnically mixed village of Dhali during the civil war (PIO 1965f, 2).

As is evident from the above excerpts, the inclusive and exclusive discursive framing strategies of boundary expansion and contraction were not solely employed by Greek-Cypriot political elites for collective self-definition through the identificatory ideologies of Greek nationalism, Greek-Cypriotism, and Cypriotism, but were also utilized to frame Turkish-Cypriot collective ethno-national identity. This finding indicates the analytical difficulty in attempting to provide an interpretative account of the unequivocal discursive manifestation of the three conceptually distinct ideologies.

For instance, Clerides’ contextually specific choice to characterize Turkish-Cypriots as “Turkish compatriots” (PIO 1967a, 2), if removed from the context of the civil war clashes, could exemplify an attempt to expand the boundaries of ethno-national identity through the ideology of Cypriotism that pursues a common patriotic affinity between Turkish-Cypriots and Greek-Cypriots. However, when Clerides’ discernibly inclusive characterization is juxtaposed with his perception of Turkish extremism (PIO 1967a), its Cypriotist quality dissipates and gives way to an exclusive process of boundary contraction that is not explicitly accounted for by the previous theorization and coding criteria (see Supplementary Appendix Table A1) regarding the Greek-Cypriotist or Greek nationalist discursive indicators of fission and fusion. In turn, this noteworthy ambiguity points to a theoretical gap in research concerning how the socially distinct other (Triandafyllidou Reference Triandafyllidou1998) was historically constructed through the different ideological lenses of Greek-Cypriotism and Greek nationalism, which arguably conceived Turkish-Cypriot and Turkish individuals as the ethno-national other (Loizides Reference Loizides2007; Mavratsas Reference Mavratsas1999).

Sovereignty and the “People of Cyprus”

According to the Treaty of Guarantee, signed in 1959 under the Zürich-London Accords which established the legal basis for the constitution of the Republic of Cyprus (Kıralp Reference Kıralp2019), the territorial sovereignty and preservation (Elden Reference Elden2006, 11) of the newly independent federal state would be safeguarded by three guarantor powers: Turkey, Greece, and Britain (Dodd Reference Dodd2010; Doyle and Sambanis Reference Doyle, Sambanis, Doyle and Sambanis2006). From the outset of the Cypriot Civil War, Foreign Minister Spyros Kyprianou, acting as the Greek-Cypriot delegate to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), sought to maintain the sovereignty of the Republic of Cyprus by asserting that the mainland Turkish government – with its role as a guarantor power – aimed to intervene to enforce an ethnic partition of Cyprus (Dodd Reference Dodd2010, 60). Alongside this, in his memoirs, the now-deceased Clerides (Reference Clerides1989) argued that the Makarios administration pushed back against the implementation of the second iteration of the partitionist “Acheson Plan,” which was proposed by Dean Acheson – the former U.S. Secretary of State – in 1964 to bring an end to hostilities, as it outlined the establishment of a Turkish military base in Cyprus that would function upon “conditions of sovereignty” (Dodd Reference Dodd2010, 68–70). The fervent denial and unwillingness of Greek-Cypriot elites to accept the Acheson Plan, which would challenge the sovereignty of the Republic of Cyprus through the creation of a self-governing Turkish military base on the island, indicates the considerable symbolic significance that the effective and unchallenged territorial sovereignty of the Republic of Cyprus held in the eyes of Greek-Cypriot elites during the 1963–1967 civil war.

On July 29, 1965, in an official statement that criticized the Treaty of Guarantee and its impact on the sovereignty of Cyprus, Kyprianou claimed that the “[t]reaty […] was imposed on the people of Cyprus” (PIO 1965d, 1). By avoiding to frame an explicit ethno-national distinction between Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot individuals and instead referring to the amalgamated “people of Cyprus” (PIO 1965d, 1), Kyprianou engages in an inclusive process of boundary expansion which, at first glance, is indicative of Cypriotism. Notwithstanding this, in discussing the independence of Cyprus, effectively an outcome of external and internal sovereignty (Elden Reference Elden2006, 11), Kyprianou challenged a report by the newspaper Patris, which, in his perspective, did not “contribute to the unity of the Greek front” on the matter (PIO 1965b, para. 1). For Kyprianou, and according to him, for the “Cyprus Government,” the ultimate result of independence would be the “union of Cyprus with Greece” (PIO 1965b, para. 1). This emphasis, which is placed by Kyprianou on the sustainment of a consensus regarding Cypriot independence and Enosis among the unitary “Greek front” (PIO 1965b, para. 1) that implicitly subsumes Greek-Cypriot ethno-national identity, reveals a motherland nationalist dynamic of boundary expansion that contradicts the previous Cypriotist indication.

Correspondingly, on a separate occasion, Makarios’ discourse engages in this process of boundary expansion, which exhibits a link between the sovereignty of Cyprus and the goal of Enosis (PIO 1966b). In a rather politically charged sermon which was delivered on April 22, 1966 in the St. George Church located in Paralimni, Makarios stated that “we [Greek-Cypriots] shall continue struggling, we shall continue making a sacrifice of ourselves for the territorial integrity of Cyprus and her union with [the] mother country, Greece” (PIO 1966b, para. 1). Here, Makarios couples the norm of territorial integrity, which underscores the capacity of a sovereign state to exist on a given territory (El Ouali Reference El Ouali2006, 631), with the objective of Enosis and claims that the symbolically sacrificial actions of Greek-Cypriots during the Cypriot Civil War would persist with these values in mind (PIO 1966b). Further, in referring to the possibility of foreign intervention during the civil war, Makarios added that “blackmails [sic] from Turkey or elsewhere [would] run onto the rock of Greek virtue” (PIO 1966b, para. 3). In consideration of both excerpts, Makarios’ discursive framing strategies reveal a Greek nationalist proclivity that expands the boundaries of ethno-national identity by incorporating Greek-Cypriots into the symbolism of the “rock of Greek virtue” (PIO 1966b, para. 3) and pursues the objective of Enosis by mentioning the Greek-Cypriot “struggle” (PIO 1966b, para. 1), which is not dichotomized between supporters or critics of the political union with Greece.

Further Remarks Regarding Greek-Cypriotism and Cypriotism

Despite the aforementioned interpretative divergence between the discourse topics of EOKA and the civil war clashes, in the aggregate, Greek-Cypriot political elites primarily expanded the boundaries of ethno-national identity by engaging in the inclusivist discursive framing strategies of Greek nationalism, thus evincing a relative linguistic absence of Greek-Cypriotist and Cypriotist indications. In the case of Cypriotism, this absence was evidently anticipated, as the mid-20th century inability of Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot citizens and politicians to develop a common patriotic affiliation and Cypriot identity to counteract the ideological currents of motherland nationalism is often observed by scholars (Loizides Reference Loizides2007; Mavratsas Reference Mavratsas1999), and in certain instances also cited as one of the factors that intensified ethnic conflict and reinforced ethnic division (Coughlan Reference Coughlan and Ghai2000, 227). Ultimately, by predominantly propounding the rival slogans that “Cyprus is Turkish” and “Cyprus is Greek,” the two main ethno-national groups of the island failed to find common ground through a “civic” Cypriotist identity during the civil war (Vural and Rustemli Reference Vural and Rustemli2006, 333). In the case of Greek-Cypriotism, perhaps this absence can be explained by the fact that a postulated association with the exclusive identity and the objectives of the ethnic group may be more clearly demonstrated through specific ethno-nationalist policies rather than discrete discursive patterns, such as the reluctance to credibly enact concessions to “Greek moderates” or Turkish-Cypriots among the Greek-Cypriot political actors of the Makarios establishment (Loizides Reference Loizides2007, 181–183).

Conclusion: Possible Criticisms and Future Avenues of Research

Taking all the evidence into account, during the Cypriot Civil War, the discourse of Greek-Cypriot political elites primarily exhibited the inclusive discursive framing strategy of boundary expansion in attempting to frame Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot ethno-national identity. In terms of relative prevalence (Table 1), and in antithesis to the previous theorization, boundary expansion (fusion) was found to be more prevalent than boundary contraction (fission) in the discourse of the five Greek-Cypriot political elite figures, hence supplying the required empirical grounds for the falsification and rejection of the guiding hypothesis (H1). Most significantly, the ideological components of Greek nationalism – which featured as the core indication of boundary expansion – were employed by Greek-Cypriot elites to incorporate Greek-Cypriot collective ethno-national identity into a unitary frame of Hellenic identification in the context of the Cypriot Civil War. As mentioned previously, this observable predominance of the ideology of Greek nationalism, located on the left-hand side of the ideological spectrum of group identification (Figure 1), was paralleled with a relative linguistic absence of the exclusive or inclusive ideological indications of Greek-Cypriotism and Cypriotism.

The absence of Greek-Cypriotist indications in the discourse of Greek-Cypriot political elites is particularly noteworthy, as this ideology is commonly associated with the post-independence Makarios establishment (Loizides Reference Loizides2007), and was theorized as the primary source of boundary contraction due to its exclusionary character. In contrast to the evident mid-20th century dearth of Cypriotist patriotic affiliation (Coughlan Reference Coughlan and Ghai2000; Loizides Reference Loizides2007; Mavratsas Reference Mavratsas1999), the linguistic absence of Greek-Cypriotism led to the inference that such a salient identificatory ideology was perhaps evinced more clearly in ethno-nationalist policies instead of the discourse of political elites.

Moreover, in a broad theoretical sense, the analysis demonstrated the considerable applicability of Wimmer’s (Reference Wimmer2008) universalist ethnic boundary-making typology in explaining how ethno-national identity was framed through the mid-20th century Greek-Cypriot political elite discourse. Be that as it may, one ought to consider the main findings along with an important caveat. In framing Turkish-Cypriot ethno-national identity, Greek-Cypriot political elites contracted and expanded the boundaries of group identification through certain contextually specific utterances that did not unequivocally reflect a specific ideological inclination and were not explicitly theorized under the coding criteria of the Cypriotist, Greek-Cypriotist, or Greek nationalist discursive indicators of fission and fusion (see Online Supplementary Appendix Table A1). A case in point is Clerides’ abovementioned characterization of Turkish-Cypriots as “Turkish compatriots” (PIO 1967a, 2), which contracted the boundaries of Turkish-Cypriot ethno-national identity. This discovery highlights the ambiguity that is rooted in the effort to provide an interpretative assessment of the discursive manifestation of conceptually distinct ideologies and indicates a theoretical gap regarding how the Turkish-Cypriot and Turkish ethno-national other was historically manufactured through the ideologies of Greek-Cypriotism and Greek nationalism, something which is not systematically addressed in the literature that this study builds on – but is rather taken as a given (Loizides Reference Loizides2007; Mavratsas Reference Mavratsas1999). Concerning the ethnic boundary-making approach, this interpretative ambiguity illustrates how, conceivably, in the Cypriot Civil War context, the discursive framing strategies of fission and fusion were not solely enacted by Greek Cypriot political elites on the basis of clearly visible or defined ideological inclinations.

In discussing internal validity, one could argue that this study would benefit from a larger sample of Greek-Cypriot political elites or textual sources to probe the guiding hypothesis. While these recommendations hold merit, the relatively brief length of the study accommodated a narrower area of examination that, importantly, can serve as the framework upon which further research may expand on. Moving forward, scholars who aim to examine the historical dynamics of ethno-national identity during the Cypriot Civil War can broaden the sample of Greek-Cypriot political elites to include politically influential figures such as Tassos Papadopoulos, who acted as the Minister of Labor during the conflict (Schemmel Reference Schemmel2020), or perhaps to compare the discursive framing strategies of Greek-Cypriot and Turkish-Cypriot elites regarding ethno-national identity by employing a dialectical approach.

The elite-based account of this study, which centers around the framing of ethno-national identity in the specific historical context of the Cypriot Civil War, acts as a notable limitation to the external validity of the above findings. By solely focusing on the Cypriot Civil War to tackle the empirical gap that exists regarding this conflict (Varnava Reference Varnava2013), the analysis traded off the possibility to provide more broadly generalizable findings – which could come about as a result of a cross-national large-N investigation of elite discursive framing strategies in the context of several civil wars – for the ability to produce a thick description of the discourse of the sampled Greek-Cypriot political elites. However, Wimmer’s (Reference Wimmer2008) ethnic boundary-making typology, to some extent, serves as a mitigating factor for this lack of external validity. The utilization of this universalist perspective in the Cypriot context sets the empirical ground for future comparative research, which may seek to delineate the socio-political factors behind the congruence or divergence among the relative prevalence of boundary expansion and contraction in the discursive framing strategies of political elites during the Cypriot Civil War, and in civil conflicts that exist in other ethno-nationally divided Mediterranean polities, such as Turkey (Sarigil Reference Sarigil2010).

All in all, the main discovery that ethno-national identity was primarily framed through the discursive framing strategy of fusion rather than fission in Greek-Cypriot political elite discourse during the 1963–1967 conflict serves as an indication that emphasizes the predominantly inclusive nature of the ethno-nationalist utterances of the selected elite figures. Further, this simultaneously poses a question as to whether such a process of ethnic boundary-making was more widely evident among Greek-Cypriot individuals in the broader Cypriot polity. Following Varnava’s (Reference Varnava2017) “history from below” perspective, which seeks to delineate socio-political developments among the wider populace of a given community instead of solely focusing on the higher classes (22), observers of the Cypriot Civil War may bring more nuance to the elite-based findings of this “high politics” study by examining the discursive processes of ethnic boundary-making within the Greek-Cypriot laboring and peasant groups of the (still) divided island.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Jonah Schulhofer-Wohl for his genuinely valuable guidance, recommendations, and constructive comments while writing this article and preparing it for publication. I am also thankful to the two anonymous reviewers for their exceedingly helpful suggestions.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2021.66.