Introduction

Recent conflicts – the Russo-Ukrainian War, the Israel-Hamas conflagration – are widely framed in civilizational terms: Eurasia against the West, the Ummah against the Zionist West, and so on. Civilizations are treated as monoliths, dividing peoples, spaces, cultures and values into essentialized poles of unity. However, even within this constellation of asserted civilizational struggle, competing civilizational discourses and subjectivities arise. The Finno-Ugric world, for example, acts as but one example of a competing conceptualization of civilization that problematizes these monolithic assertions.

However, as the authors will illustrate in this article, the Finno-Ugric world is not a monolith in and of itself, being equally unfixed through its diverse articulations and instrumentalizations in agonistic competition. In addition, this article is inspired by the ongoing debate on multiculturalism in societies where mainstream ethno-linguistic identity has to coexist with smaller groups and their culturally expressed collective selves. In both of these regards, Estonia, as one of the smallest nations in Europe, is an interesting case of diversity that is integrated into the hegemonic discourse, yet in the meantime, it constitutes certain groups as domestic others that are difficult to assimilate. One of the strategies of national identity consolidation has been the situation of Estonia in the wider Finno-Ugric world after the country regained its independence in 1991.

This “reinvention of Finno-Ugric identity” coincided with the “general process of ethnic and cultural fragmentation” (Kuutma Reference Kuutma2005, 56) that followed the Soviet occupation. The national independence from 1918 to 1940 was marked by an adherence to a strict Herderite understanding of the nation delimited against Baltic Germans and Russians (Petersoo Reference Petersoo2007), with there being room for only one titular nation – Estonia – and one national language – Estonian. Language-based nationalism acted as the foundation of the National Awakening in the mid-19th century (Raun Reference Raun1991). In the consequent study of Finno-Ugric identity, its unitary nature has remained unproblematized (Brown Reference Brown and Silova2010). Such understandings echoed in folkloristic studies of the nation (Abrahams Reference Abrahams1993), which nonetheless continued during the Soviet occupation. Additionally, Finno-Ugric identity has become a focal point for the Estonian Ethnofuturist literary movement as a “nationalistic cosmopolitanism […] a local, peripheral and provincial outgrowth of postmodernism” (Viires Reference Viires1996).

Similar to how the Estonian national movement first burst forth from linguistic and folkloristic movements, this Finno-Ugricness has also expanded beyond its purely linguistic and ethnological articulations (Sommer Reference Sommer2014), representing now a full civilizational discourse. This became especially critical in discussions of national identity in the period after Estonia regained its independence. As Feldman argues in the context of Estonia’s candidacy bid for membership in the EU, “Finno-Ugric identity could protect ethnic Estonians from the homogenizing effects of Europeanization because it draws on non-Christian tropes of animism and integration with nature” (Feldman Reference Feldman2000, 417). Such a perspective would put Estonia into a wider network of cultural and linguistic relations that would maintain local identities in a world where national sovereignties had started to play less of a deciding role. At the same time, this Finno-Ugric identity is contrasted with other discourses of Estonian nationhood with which it had to compete, those being Estonia as a reconstituted state, Estonia as a European nation, or Estonia as a Nordic country.

In the previous studies, two research positions have been articulated. One treats Estonia’s Finno-Ugric identity as a political resource aimed at either protecting Estonians from the homogenizing effects of Europeanization (Feldman Reference Feldman2000, 417), or at creating an informal alliance of Estonia, Finland, and Hungary to boost EU’s policy of protecting ethnic minorities in Russia (Korkut Reference Korkut2008). Another cluster of academic works discusses Finno-Ugric identity as a cultural construct that is produced by theaters (Epner and Saro Reference Epner, Saro, Bédard-Goulet and Chartier2022), museums (Karm and Leete Reference Karm and Leete2015), and vernacular narratives (Siikala Reference Siikala and Siikala2002). The resulting representations need not be mutually exclusive and can come together in hybrid discourses. It is exactly this process of negotiation and rearticulation that this article seeks to explore, centering on the unfixable nature of Estonia’s Finno-Ugric identity.

This article seeks to synthesize these two groups of scholarship and discover how this contemporary Finno-Ugric identity has been politically instrumentalized and negotiated in Estonia at a critical juncture of EU’s relations with Russia in 2021–2022. We understand negotiation as a discursive process wherein diverse subjectivities agonistically ascribe meaning to objects of this discourse; for this article, this object is Finno-Ugric identity. To trace how this instrumentalization and negotiation takes place, we first look at how the Estonian state engages with the concept of Finno-Ugric world and inscribes it into Estonia’s foreign policy goals. Then, we delve into the role of Finno-Ugric tradition and civilization in Estonian populist and far-right discourses. Third, we discuss how local identity constitutes and cements community building initiatives and projects in the Seto region known for its local specificity and cultural peculiarity. The three cases and the corresponding three units of analysis are complementary to each other and offer different outlooks at the Finno-Ugric identity in Estonia as our main object of study.

These units were selected in accordance with a set of complementary criteria established in academic literature. One is based on dispersed political phenomena of performativity, leadership, decision-making, and institutional practices, which requires multiple units of analysis both within the state and beyond it (Gronn Reference Gronn2002, 423). In our case, we presume that the instrumentalization of Finno-Ugric identity is distributed among the state, one of major political parties and local communities. Another criterium connects units of analysis with authority patterns, or clusters of the most influential actors in the researched domain (Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Gurr and Jaggers2002, 40); in this sense, the governmental apparatus, a nationalist party and subnational authority in a culturally specific locality, seems to encompass the most significant patterns of different types of power relations. One more approach to the selection of units of analysis is through the concept of implementation structures that “can coordinate and control collective action” (Hjern and Porter Reference Hjern, Porter, Holzner, Knorr and Strasser1983, 265), which again justifies the triad we opted for in this analysis.

Our time frame is limited to the period of 2021–2022 marked by an incremental conflictuality between Russia and the entire Euro-Atlantic international society, which particularly affected countries that share borders with Russia, Estonia included. Apart from sanctioning Russia for the annexation of Crimea, in 2021 the EU reacted to the imprisonment of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny by introducing a new package of sanctions. The mutual alienation was conducive to the further collapse of the entire architecture of Russia’s relations with the West after Russia’s ultimatum demanding a rollback of NATO to the 1997 positions and the ensuing military intervention against Ukraine. It is against this geopolitical background that we scrutinize the three layers of instrumentalization of Finno-Ugric identity in Estonia. Evidently, each of them was affected by the geopolitical crisis in its own way. For obvious reasons, the foreign policy layer faced major repercussions of Russia’s confrontation with the EU and NATO, which became a major challenge to Estonia’s security as a potentially frontline state. On the national level, the drastic deterioration of relations with Russia was a crucial factor for the Estonian far right, which had to find a new balance between political pragmatism and identitarian idealism. As for the subnational level, local and ethnically specific communities were affected by border lockdown that started as an anti-pandemic measure and then became an instrument of isolating Russia through diminishing trans-border mobility and connectivity, which previously allowed the family members to easily cross borders since the re-independence of Estonia in 1991.

This study uses a variety of mutually compatible methodological approaches in each of the three sections. Through this article we engage with the same discursive focus — Finno-Ugricness — from three distinct yet interrelated Estonian contexts. By examining the phenomenon from multiple angles, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of its complexities. In all three cases, our main focal points are identities and cultural borders that are core for understanding different facets of Finno-Ugric identity in Estonia. For the Estonian officialdom, we mostly use visual observation of the World Finno-Ugric Congress held in Tartu in June 2021, along with the video recorded opening ceremony of inaugurating Abja-Paluoja as the 2021 Finno-Ugric capital of culture. For the EKRE (Estonian Conservative People’s Party) part of the analysis, a combination of discursive and visual analytical approaches is applied to explain how Finno-Ugric identity is used to justify the contemporary representation of the Estonian nation by the local far right.

The community building section is grounded in an experience of visual anthropology and field research done in Obinitsa and Varska over a year on multiple visits to the region. Interviews and photographs were obtained on various community events including the Seto Kingdom day, Cafe Day (Kostipäev), Easter, and Transfiguration day feast (paasapäiv). Interlocutors for this research were chosen among a pool of local residents ranging from the artists, community leaders, and opinion makers. Duration of these semi-structured interviews varied from 30 minutes to over an hour, and some of the participants were interviewed more than once. This approach to data collection is based on the research methodology of visual ethnography with the focus on the sociocultural aspect of the Setu community. Photographs obtained through this field work complement the traditional method of ethnographic studies and thereby provide additional understanding of the aesthetic and artistic aspects of identity making through emotions and feelings (Given 2008). As scholars point out, richer meanings of reality are produced when text is multiplied by images (see Bateman, Reference Bateman2014; Kress and van Leeuwen, Reference Kress and van Leeuwen2020). This mixed-method approach allows us to uncover possible multiplicities in the articulation of Finno-Ugricness, which may otherwise remain overlooked.

A note on positionality seems to be important at this juncture: all three co-authors are Estonian residents with non-Estonian background, which is both a challenge to and an asset for our research practices. Such positionality allows for a nuanced perspective of this phenomenon, as the bulk of previous studies of Finno-Ugric identity are primarily conducted by those within the self-ascribed Finno-Ugric community. Recognizing this positionality allows us to be conscious of our own experiences and biases, thereby giving valuable insights into the focus of the study that might otherwise be treated as natural or characteristic of Finno-Ugric without any critical examination. This awareness can help us to understand the implications of our research and its potential ramifications, while also allowing us to question and interrogate the assumptions we and others might make about the context of our research. Our knowledge is situated (Rose Reference Rose1997) in a variety of academic gazes all bent on a certain distance between us as researchers and objects of our study. Furthermore, visual materials not only reflect the aesthetic choice of an author but also represent the positionality while explaining a significant sociopolitical situation (Bleiker Reference Bleiker2019).

Theories and Methods

Our analysis is grounded in three mutually compatible and reinforcing theoretical concepts and approaches that have sparked vivid and lengthy academic debates and produced useful interdisciplinary perspectives on issues of identity and multiculturalism. The first reference point is the concept of floating signifiers, i.e., the notion that signifiers as such do not have any pure symbolic value and are used contingently and relationally by political actors to construct identity and delineate relations of amity and enmity (Laclau Reference Laclau2005); this explains how different meanings can be infused in the ideational constructs used to describe and make sense of political phenomena. The logic of the floating signifier, as articulated by Ernesto Laclau (Laclau Reference Laclau2017; Laclau and Mouffe Reference Laclau and Mouffe2001), implies that in political parlance there might be multiple interpretations and versions of concepts that in fact function as metaphors susceptible to subjective readings and contextual understandings. For Laclau, social reality is seen as multiple chains of equivalences ontologically linking specific objects and concepts to each other (Hansen and Sonnichsen Reference Hansen and Sonnichsen2014, 257). The discursive fixation of the meanings attached to those concepts is feasible only through the appearance of a signifier that linguistically, materially, or visually represents the whole chain (Stengel and Nabers Reference Stengel and Nabers2019, 259) yet semantically may move from one regime of signification to another. This representation functions through constitutive references to universal norms, principles, or values, yet it can be only provisional and contextual, as those universals are equally dependent on fluctuating references stemming from the political demands of diverse and often competing groups – in the context of this analysis, these groups would be the three loci of state institutions, a nationalist political party, and an enterprising subnational authority. Methodologically, this means that our approach is sympathetic to that of the Essex School, which takes its inspiration from Laclau’s rationale (Glynos and Howarth Reference Glynos and Howarth2007). In our analysis, we treat the concept of Finno-Ugric identity as an empty signifier that might be differently represented, narrated, and visualized, depending on who produces the variegated discourses and images and what policy practices are born out of them.

Our second theoretical point of departure is the aesthetic turn in political science and international relations. Aesthetics is closely related to representations and significations through which political concepts come into being. As Roland Bleiker puts it, many political phenomena – identity, multiculturalism, religion, democracy, and so forth – are not visible beyond their representations, and therefore inherently include visualized aesthetic components. According to his theory, aesthetic approaches “acknowledge that there is always a gap between a representation and what it represents. This gap is not only inevitable but also of key political importance for it has to do with collective conventions that determine which one of numerous plausible explanations are considered legitimate and which ones are deemed unreasonable or illegitimate” (Bleiker Reference Bleiker2017). He conceptualizes the field of politics (and therefore politicization) as the inevitable aesthetic gap between what is represented in discourses and imageries, and how it is represented. Consequently, depoliticization connotes a sort of mimetic congruency between signs and symbols, on the one hand, and the signified and symbolized social or cultural reality, on the other.

Finally, our last source of academic inspiration is the theory of performativity developed by gender scholar Judith Butler and her multiple followers. It is premised upon the impossibility of fixed or anchored identities and, consequently, the multiplicity of signifiers that might be altered in a playful combination of different roles and forms of subjectivity. Butler argues that identities are performed (enacted, expressed, produced, dramatized, and constituted) through acts that bear resemblances to theatrical style (Butler Reference Butler1988, 521). Therefore, identity “is not something one is, it is something one does in […] a sequence of acts” (Butler Reference Butler1999, 25) that constitute a reiterative basis for political agency. This is exactly how we discuss Finno-Ugric identity in this article – as a series of performative gestures and moves with different intentionality, styles, and scripts.

The common denominator that conditions the application of all three theoretical vistas is a civilizational identity of the Finno-Ugric world that is manifested through practices of the social actors that constitute and instantiate the civilizational reality (Bettiza Reference Bettiza2014, 3). In line with Laclau, Bleiker, and Butler, one may posit that “sedimented social practices – no matter whether they manifest themselves in rituals, in cultural identities, or in functionally predetermined rules and institutions – gain objectivity because they can be anticipated on the basis of their repetitive nature” (Marchart Reference Marchart2014, 273–274). In this vein, it is the assertion of Finno-Ugric civilization as a social fact, a foundational, objective, existential, and authentic condition of identity-making that plays the role of the signified in multiple discourses and imageries that we study. In this way, authenticity in political communication has been noted as the “demand for the honest, the natural, the real” (Potter Reference Potter2010), from which we can infer that politicization of identity as a social and cultural construct “cannot be limited to epistemology, but has ontological consequences” (Hansen Reference Hansen2014, 283).

We also focus on this authenticity as it is performed (Luebke Reference Luebke2021) by interlocutors of this asserted Finno-Ugric civilizational community. We study where its identity is situated in constructing these discourses of authenticity as either reinforcing Estonia’s politics of belonging to Europe, or underscoring Oriental (Uralic) roots of Estonian identity. Both options give Estonia a chance to politically address its Finno-Ugric cultural brothers and sisters from a normatively European perspective. Within this explanatory frame, floating signifiers function as parts of the aesthetic sphere, and provide a discursive basis for performative practices. Performativity and aesthetics in this respect are the two sides of the same coin.

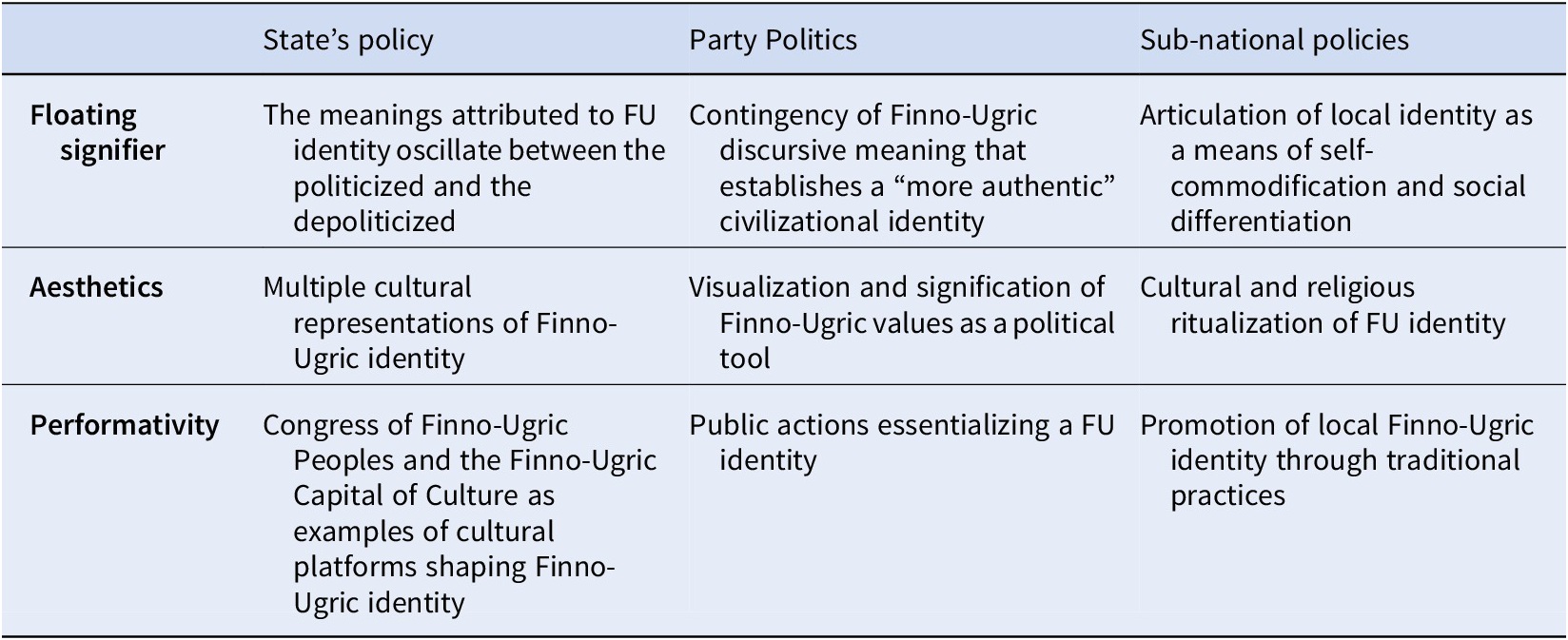

In Table 1, we show how the three main concepts are applicable for studying different units of Estonian politics – policies of the state, party politics, and local cultural milieux:

Table 1. Three analytical concepts and their application

This theoretical background explains the advantages of visual analysis as a research method we prefer in this study. For Judith Butler, visuality is “a modality of performativity” (Bell Reference Bell1999, 7). In conducting social science research, ethnographers used visual forms for generations (for example, Edward Curtis used photography to study Native Americans). Susan Sontag and John Berger wrote about photography as a medium to collect and preserve a series of anecdotes of the past and the present, and therefore to construct meanings (see Berger Reference Berger and Dyer2013; Sontag Reference Sontag1979). Additionally, photographs obtained from the fieldwork serve as an aide-memoire in creating a visual documentation of a sociocultural phenomenon. Such methods as photo-documentation and photo-elicitation serve as supportive materials to research as well as data in visual research (Tinkler Reference Tinkler2013; Rose, Reference Rose2016). The method used in this research is comparable with the “grounded theory” approach explained by Strauss and Corbin in which the social science research is constructed through related evidence obtained from the fieldwork (Strauss and Corbin Reference Corbin and Strauss2008; Rose, Reference Rose2016).

With all this in mind, the Finno-Ugric civilizational identity is represented in various forms and genres and through multiple signifiers that reach out to different audiences. As part of the public space, the performative aesthetics of Finno-Ugric civilization becomes visible through museum exhibitions, folk festivals, art projects, and public events that are grounded in the visual appeal and different forms of visibility. In the following sections, we show how this approach might be used to analyze the functioning of Finno-Ugric identity in the context of state policies, domestic party politics, and community-building.

The Estonian State and the Finno-Ugric World

The fundamental ambiguity of the Finno-Ugric identity is well illustrated by its instrumental use by the Estonian state. In this section, we dwell upon two specific events of 2021 – the World Congress of Finno-Ugric Peoples held in Tartu and the inauguration of the town of Abja-Paluoja as the Finno-Ugric capital of culture. Both events will be scrutinized through the lens of the logics of politicization and depoliticization closely intertwined in the field of the state’s interaction with public institutions and organizations. These cases are illustrative of how state authorities are integrating voices of supporters for Finno-Ugric traditionalism and tribalism into the official discourse to performatively enacts and empowers ethnic authenticity (Scandza Forum 2020).

From a political perspective, the Finno-Ugric identity is an instrument of cultural policy bringing Estonia closer to Finland and Hungary, two countries that shared institutional partnerships – through the EU and NATO – that go beyond simple ethnolinguistic ties. However, the historical and cultural genealogy of Estonia’s Finno-Ugric identity gives a clear indication of its Oriental roots, which may contradict the hegemonic narrative of Estonia’s inherent civilizational belonging to the West, and underscore important ethno-cultural and linguistic connections that tie Estonia to Russia.

A perfect visual example of this ambiguity is the Estonian National Museum, a home to the World Finno-Ugric Congress held in June 2021. The overall aesthetic concept of the museum exposes a “tension between a romantic ideology of an old nation defined through its history and peasant heritage, and a democratic, fully transformed state of liberal values” (Pawłusz Reference Pawłusz, Kullasepp and Marsico2021). The Finno-Ugric part of the permanent exhibition (Echo of the Urals 2021) visually prioritizes the “eastern” (Uralic) connections of the Estonian identity, and says much less about the role of Hungary and Finland in the Finno-Ugric world, which is explained by the fact that these two countries have their statehood and are well-established political actors.

This distinction seems to be a good starting point to explicate how Finno-Ugric civilizational identity is used for underlining Estonia’s cultural authenticity, which might serve as a basis for this country’s soft power and people-to-people diplomacy when it comes to relations with Finno-Ugric regions in Russia. With the Finno-Ugric concept in hands, Estonia positions itself as a source of inspiration and a successful example of political and economic transformations for kindred Finno-Ugric people. A good visual illustration of this logic can be found in the ceremony of inauguration of the town of Abja-Paluoja as the Finno-Ugric capital of culture in 2021 (Estonian Saunas 2021). The then president Kersti Kaljulaid in her speech emphasized the commitment of Estonia as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council to defend the rights of indigenous people, while former president Toomas Hendrik Ilves expanded the space for political meanings further on: “Despite Soviet atrocities we in Estonia are free, and we know better than some larger countries how vulnerable are national identities and languages, and what does it mean to live in oppression.” This logic was continued by Estonian MP Helir-Valdor Seeder who underscored that only three Finno-Ugric nations – Estonia, Finland, and Hungary – have their states and can take care of their languages, while “there are other Finno-Ugrains who live in territories rich with mineral resources, but can’t organize their everyday lives as they wish.” This argument was aesthetically contextualized by direct symbolic references to a Finno-Ugric village in the Russian region of Mari El and a performative appearance of representatives from Mordovia (ART Konverentsitehnika videod 2021).

Therefore, the Finno-Ugric track in communication with Russia is considered important, yet the Estonian agenda in this policy area reaches beyond purely cultural domain, which produces another ambiguity: Estonian government emphasizes the political distinction between Estonia and Finno-Ugric ethnic communities in Russia, yet in the meantime Kersti Kaljulaid, after her controversial visit to Moscow in April 2019 (Baltic Monitor 2019), invited Vladimir Putin to the World Congress of Finno-Ugric Peoples in Tartu, which was initially scheduled for June 2020 but due to the pandemic took place in June 2021. Formally, the World Congresses of Finno-Ugric Peoples are representative fora of the Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic peoples and are independent of governments and political parties. However, host states often use Congresses for contributing to the accomplishment of such objectives as development and protection of the national identity, cultures, and languages of Finno-Ugric peoples, promotion of cooperation between Finno-Ugric people, and support for their right to self-determination in accordance with international norms and principles. Due to a high public visibilityFootnote 1 and inevitably politicized discussions, Congresses attract the attention of governments and may serve as litmus tests of their intentions of using this forum either as an instrument of soft power or as a tool for confrontation.

Estonia has always promoted Finno-Ugric identity – including through World Congresses – as an instrument of soft power, and the idea to invite Putin to Tartu was part of this thinking. This initiative that came from the office of the Estonian President was sustained by some Estonian speculations about Putin’s alleged Finno-Ugric roots (ETV Pluss 2019), which was naively expected to facilitate his appearance in Tartu. However, these plans were not materialized. Not only did Putin ignore the invitation to visit Estonia, but Russian Association of the Finno-Ugric Peoples boycotted the Congress, accusing the “international Finno-Ugric movement” – and therefore, paradoxically, such traditionally Russia-loyal countries as Finland and Hungary – of unduly politicized interference into Russian domestic affairs (“Заявление Ассоциации Финно-Угорских Народов России” 2021). This only furthered a political tone of the debate: Tõnu Seilenthal, a member of the Estonian Consultative Committee of Finno-Ugric Peoples, blamed Russia for creating an “iron curtain” (Tambur Reference Tambur2021), while the Russian Foreign Ministry accused the Congress organizers of intentionally mistranslating “Russia’s support for cultural specificity” as “support for self-determination” in the video recorded speech of the Russian Minister of Culture at the opening ceremony (“Комментарий Официального … 2021). In a more conspiratorial way, a pro-Kremlin media portal presumed that it is Ukraine that might be interested in – and therefore stand behind – the political attention to the Finno-Ugric peoples living in Russia (Финно-угорский вопрос… 2021).

Another politicizing criticism to the Congress was given from a completely different side – by the elder of the Erzya people Syreś Boläeń who staged a solo press conference in front of the entrance to the National Museum, which symbolically positioned him as being both inside and outside of the Congress venue. In his speech, he argued that Estonian authorities’ desire to entice Putin into Tartu has transformed the concept of the World Congress from an open forum for public debates into a predominantly cultural and depoliticized event predominantly focusing on musical and dancing elements of Finno-Ugric traditions, completely devoid of a possibility of raising such sharp questions as, for example, the suicide of the Finno-Ugric activist Albert Razin in Izhevsk and other incidents illustrative of the state of affairs in Russian Finno-Ugric community (Syreś 2021). Boläeń’s criticism of the Congress hosts for their policy of coordinating participants’ registration procedures with Russian authorities sheds additional light on the overwhelmingly politically sterile model of the event that its organizers adhered to.

What the analysis in this section has shown is two different strategies of instrumentalizing the floating signifier of the Finno-Ugric world within the Estonian establishment. One is bent on an explicit politicization of relations with kindred peoples in Russia through a hierarchical differentiation between them (oppressed and subjugated to the system of Russian “domestic colonialism”) and free Finno-Ugric nations that have successfully achieved independence and freedom. This narrative – personified, in particular, by the former President Toomas Hendrik Ilves – boosts Estonian speaking position within the transnational Finno-Ugric movement and can be translated into a mix of cultural diplomacy and soft power. The second, a much more depoliticized position, was taken by another former head of the Estonian state Kersti Kaljulaid who was keen on using the formal Finno-Ugric platform for incentivizing President Putin to visit Estonia and thus maintain a communication channel with the Kremlin. Remarkably, none of these strategies properly worked. On the one hand, Moscow has qualified attempts to directly appeal to Russia’s Finno-Ugric communities as interference into Russian domestic affairs and started creating its own internal “Finno-Ugric world” (Kuznetsova Reference Kuznetsova, Bogdanova and Makarychev2020). On the other hand, the idea of enticing Putin to Tartu has also failed; moreover, the local organizers of the Finno-Ugric Congress were blamed for intentional depoliticization of the Finno-Ugric agenda and abstention from discussing issues of content for the sake of political neutrality and diplomatic correctness. This ambiguity demonstrates how the concept of the Finno-Ugric world discursively functions as an interplay of politicization and depoliticization as competing yet mutually conditioning performative strategies that pop up at the intersection of state-led policies and cultural practices and institutions.

The Travelling Forest: Finno-Ugric Identity and the Far Right

In the Estonian radical right, which is represented primarily by the Eesti Konservatiivne Rahvaerakond (EKRE) and its youth wing Sinine Äratus (Petsinis Reference Petsinis2019), Finno-Ugric identity also maintains a situationally ambiguous – and thus “floating” – nature. It is also the only party on the national level that directly engages in negotiations of Finno-Ugric identity. In the discursive chain of equivalences, to use the language of Laclau, three main elements can be noted. First, Finno-Ugricness represents a secondary attribution alongside Estonianness, with Estonianness establishing a modality of quintessential Finno-Ugricness. Second, it provides a reference point for establishing relations of closeness with other nations, as well as amity and enmity with other actors. Last, the employment of Finno-Ugric identity represents a civilizational discourse that can provide authenticity for those who claim to speak on its behalf. In this way, the wider Finno-Ugric civilizational theme acts as the cultural and historical grounding for the “genuine” Estonia, on behalf of whom EKRE, Sinine Äratus, and individual interlocutors perform as the legitimate representatives. Even within the milieu of the Estonian ethnonationalist right, Finno-Ugric civilization remains a conceptually unfixed, floating signifier, sedimentary to political demands.

The main body of the party primarily treats Finno-Ugric identity either as synonymous to Estonianness or as a genealogical attribute of the historical Estonian nation. There is no extrapolation as to its meaning in the party program. EKRE members of parliament have voted in support of the precarious cultural position of the Finno-Ugric peoples within the Russian Federation (“EKRE: Riigikogu peaks tegema avalduse Venemaa põlisrahvaste toetuseks” 2021), but in a more systematized, direct fashion, it is not articulated, defined, or interpreted on any theoretical level that fixes it to specific concepts. Nonetheless, this Finno-Ugric identity is still stressed vis-a-vis its relationship to Estonianness in that it prefigures and conditions it.

The online news portal for EKRE, Uued Uudised, provides a wider space for the articulation of this last point in the form of visualized individual news stories and op-eds. Most of these stories are several paragraphs and either reproduce reports from elsewhere or act as a forum for the opinions of individuals from the party. For example, a story suggesting Donald Trump is a Finno-Ugrian due to his Rurikid ancestry (due to the Rurikid paternal N1c haplogroup) is presented to claim him as a member of the Finno-Ugric community (“Donald Trumpi esivanemate seas on muistsed soomeugrilased” 2016). The ascription of Finno-Ugricness as a qualifier was also obliquely used to mark certain personality characteristics, with Estonian President Alar Karis being described as “balanced Finno-Ugrian” in comparison with the “temperamental” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky (UUED 2022). These two examples demonstrate the two extremes of the spectrum in which the meaning of Finno-Ugricness is articulated and temporarily fixed. Essentialized in both ancestry and personality traits, Finno-Ugricness is actualized both through performed style and being.

Additionally, EKRE did react to the state’s efforts regarding the debate around the 2021 Finno-Ugric Congress, claiming that the Estonian state’s failures to engage with the Kremlin in such a depoliticized, cultural format only proved the party’s “pessimism” regarding the eastern neighbor to be well founded (UUED 2021). Nevertheless, this mention of the 2021 Congress was only peripheral to Põlluaas’s polemic against the government’s policy toward Russia more generally.

In this way, one of the primary roles of the news portal is to act as a staging ground for certain narratives arising from factions of the party. Through Uued Uudised, it is more the youth wing of the party, Sinine Äratus, that is able to bolster its own discursive claims and assumptions regarding Finno-Ugricness and its related meanings. The symbol of the organization, a stylized version of the Põhjatäht or north star, provides a direct visual link between Estonian and Finno-Ugric identities through a reference to the axis mundi of Finno-Ugric mythology (Frog, Siikala, and Stepanova Reference Frog and Stepanova2012). It is designed in the same aesthetically Ethnofuturist patterns as the Uurali Kaja section of the Estonian National Museum (“Uurali kaja” 2016), reminiscent of the ownership marks from Mari and Udmurt villages. In this vein, Sinine Aratus directly states in its program that “art, public space and architecture with a state function must be consistent with Estonian, European and Finno-Ugric traditions, culture and history” (“Programm” 2021), which takes an actively aesthetic approach in their treatment of such a sphere of publicly visible culture. The importance of such visibility would therefore imply that each of these identities – Estonian, European, and Finno-Ugrian – are elements of one discursive chain and must be performed accordingly.

Nonetheless, visually performing this Finno-Ugric identity is not a main goal or strategy of neither EKRE nor Sinine Äratus in asserting its substratal status or centrality to Estonian identity. The most public performance that the party makes is its torchlight rallies for the 24th of February Victory Day celebration, which was instituted by Sinine Äratus in 2014. Nonetheless, it was other radical right parties in the region, specifically Latvia’s Nacionālā Apvienība, that led the way in the contemporary establishment of such an event based on their own national historical traditions (Auers Reference Auers2023). This is the most well-known event held by the party (Braghiroli and Petsinis Reference Braghiroli and Petsinis2019), and it has been replicated in practice by other right-wing movements, including the infamous 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia (Innes et al. Reference Innes, Innes, Roberts, Harmston and Grinnell2021). This demonstrates that the primary publicized aesthetic practice of the radical right remains centered on a nationalist understanding of identity and identity-affirming practices rather than on a more civilizational one.

Beyond this, Finno-Ugric identity serves as a discursive reference point for establishing close relations with other nations and, as a result, is used to distinguish between amity and enmity. For example, Sinine Äratus issued a statement of support to the Hungarian government in 2018 over a EU parliamentary censure due to alleged breaches of European values. At the time, there was debate on whether such breaches would constitute the calling of Article 7 (BBC News 2018), which would have suspended some of Hungary’s rights as an EU member state. In this context, the Sinine Äratus statement stressed that the support for their “brothers” was first predicated on their “common Finno-Ugric ancestry” but also on their “shared historical experience in struggles against various multicultural empires over the last centuries” (Sinine Äratus 2018). In this configuration, the Hungarians are positioned as a paragon “not only for its Finno-Ugric brothers, but for all European peoples” under the newest iteration of a supposedly multicultural empire, “the ideological dictatorship of Brussels.” While EKRE has supported the policies of other right-wing or radical right parties through Europe, such as Poland’s Prawo i Sprawiedliwość against Brussels (Raik and Rikmann Reference Raik and Rikmann2021), the justification of such solidarity has been on ideological – and not civilizational – grounds.

Therefore, within this specific social logic, all that matters is that the Estonians and Hungarians have a familial relationship based on this brotherhood, and it is these relations that is the first ordering principle of support. Additionally, this Finno-Ugric brotherhood is nested within a wider European identity that is contrasted – not with Europe per se – but specifically with Brussels. More nuanced interpretations of either Finno-Ugricness or Europeanness are not articulated here, leaving only the contraposition of these authentic nations against a “false” representation that labels itself European. For Sinine Äratus, Finno-Ugric identity is stressed although it still remains subordinate to the Estonian national identity.

It is exactly the position of Finno-Ugricness as a node of affinity that lends to its importance, especially in relation to justifying or contesting this affinity with other national or civilizational labels. Through inspiring a “new national awakening of Estonians,” Sinine Äratus would “give Estonians their self-awareness among other Finno-Ugric and European nations” (“Meist” 2021). This self-awareness informs concrete foreign policy goals, being the “support the aspirations of small peoples for freedom, which have been repressed by the great powers, especially in the case of the Finno-Ugric peoples” (ibid.). The salience of this relationship is especially pronounced in the Hungarian case.

Nevertheless, individual articulations provide meaning to this floating signifier of Finno-Ugric identity and its relation to the historical Estonian nation, with the most vocal proponent being the one of the founders of Sinine Aratus, Ruuben Kaalep. Being a member of the Estonian parliament, he has often contrasted Estonia’s Finno-Ugricness with contemporary “European” civilization, i.e., the post-Enlightenment Europe of liberal democracy and universalism of values and norms. In fact, by stating that “the Finno-Ugric people have nothing to do with the ideas born of the French Revolution” (EKRE 2018), Kaalep cleaves the Finno-Ugric civilizational identity off of the genealogical root of the Enlightenment as a prepartum seed of a modern Finno-Ugric civilization, as it is often situated for Western civilization.

It is in fact with this chasm in mind that the Finno-Ugric world’s suture with Europe and the West is presented. Vis-à-vis this presentation of authenticity, the relationship of the two is articulated as a battle between traditionalism and modernism, as well as a path for political action in the future:

The rebirth of Europe free from the paradigm of the previous civilization, in the sense that its materialistic emphasis on thought and form will be replaced by an authentic essence. And this essence will be found in Finno-Ugric as well as Baltic, Slavic, and Germanic ancestral connections with our tribes and our soil… I can never take this degenerate Western civilization seriously or lament its downfall because as an Estonian – and the same goes about Finns – the spirit of my people was never part of this West. We never lost our connection with nature, with our land, with our mythology. Western Europeans lost it a long time ago. They went outside the forest, they became afraid of the forest, they escaped to the cities. We will bring them back. (Kaalep Reference Kaalep2018)

Estonia here is made central to both the Western and Finno-Ugric civilizational discourses, as it is presented as the exemplar of authentic civilizational identity. Western European civilization identity, in being universal, has become so abstracted to the point of the concept being empty. In negating this empty identity, the Estonian nationalist contraposition instead is the real, legitimate one. The archaic, mythopoetic past of “Finno-Ugric shamanism” synthesized with “a thousand years of Christian Europe” put the Estonian as the interlocutor of both (UUED 2016). In this way, the Estonian nationalist movement can therefore act as an exemplar in the return of all ethnic groups back to the authentic “ancestral lands” of the forests from these cosmopolitan cities, as a loose political strategy that runs in parallel to the Nouvelle Droite concept of ethnopluralism (Spektorowski Reference Spektorowski2003). Such articulations are in line with similar developments in the European and Western far right that tie in with claims of pre-historical “Aryan” or “Hyperborean” civilizational kinship affinities (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2015; Sedgwick Reference Sedgwick2019).

In this more specific ethnonationalist paradigm, Finno-Ugric identity is deployed not so much as to orientalize Estonia as the state-level discourses do, but instead to delegitimize discourses on the universality of Western values and their applicability to the Estonian nation. The pivot to Finno-Ugric identity as a top-level attribution represents something akin to civilizationalism amongst the Western European far right (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017), wherein a post-secularized historical community relies on that shared history as the justification for shared values and identity beyond the scope of nation alone. For the Western European radical right, this is Christendom; for EKRE, this is Finno-Ugric identity as it overlaps with Europe.

In either configuration, there is nonetheless an “authentic” particular cultural identity that is claimed as “ours” against a counterfeit, cosmopolitan universalism. In contrast with the Estonian state-level narrative, Finno-Ugric identity is not solely a forum for marketing the country or engaging in acts of paradiplomacy but rather a discursive alpha point from which to claim legitimacy over the current government, albeit in an oblique manner. However, this is not characteristic of the Estonian ethno-nationalist right as a whole. EKRE acts as a platform for Sinine Äratus’s discourse on Finno-Ugric identity, which hints at a future civilizational focus as the leaders of the youth wing vie for party leadership in the coming years, with more markedly political demands to fully fix the meaning of that civilizational identity to a specific semiotic anchor. Consequently, this process leaves space for the future performance and reiteration of that identity as it gains its centrality.

The Seto Community: Local / Subnational Dimensions

At the sub-national level, the Finno-Ugric culture is actively promoted by the Seto community. Obinitsa village in Setomaa was awarded the Finno-Ugric Capitals of Culture in 2015, an initiative to strengthen the identity and awareness of Finno-Ugric people. Setos in Estonia carved out a niche way of community building through arts and performativity. The primary goal of this section is to highlight the importance of visual identifiers and performative elements in conjunction with the emergence of visual politics as a research field in political science that could provide new and relevant venues to study the identity construction of the Seto people. This section illustrates two aspects: first, the struggle to establish Seto as a unique language rather than a dialect, and second – the role of commodification of culture (music, food, and costumes) enabled the Seto community in promoting their identity at both national and global levels and in highlighting their endeavors to overcome their status of a marginalized community. In addition, this section explores the use of visuality as a grounding technique in the process of identity construction. Before diving into nuanced explanations, it is essential to place some of the key issues in their historical and cultural context.

The peculiarity of the Seto community lies in their religious and linguistic specificities, combined with the political fate ensued since the signing of the 1920 Tartu Peace Treaty (Jääts Reference Jääts2000) between Estonia and Russia that determined the ethno-territorial border to all of Setomaa – a region encompassing south of lake Peipsi extending to Petseri district (Pechory Rayon) in current Russia (Kaiser and Nikiforova Reference Kaiser and Nikiforova2006). Between 1920 and 1940, the Estonian Republic elites began assimilating the Seto community in the Petseri region to mainstream Estonia by providing assistance to improve local educational and economic standards; the “cultural revolution” of the Seto community took place through compulsory education in Estonian as a language of instruction at newly created schools, and Estonian language religious services in the Orthodox churches in the Seto community. However, the ethnic Russians were left behind in the process of assimilation. Furthermore, the Seto congresses held in 1921 and 1930 were hosted by the Estonian authorities with the aim to integrate Setos with the rest of Estonia. The sociocultural life of Setomaa became more active through these events (Jääts Reference Jääts2000), which is reflected by stories of the Soviet times played at community theater events by local cultural activists from the community, including former Chief Herald Horn Aare. For Ulle Kauski, a writer who lives in Obinitsa, despite being painful it is important to recollect the “evil past” recreated through satirical plays (Kauski Reference Kauski2022).

Though the Setos were not completely accepted by the majority of Estonians and were looked down upon as an “outdated and backward” group, the Orthodox religious practices and traditional costumes and folklore singing (Leelo) remained aesthetically significant in everyday social practices. Many Setos gained a high level of education and thus “Seto intelligentsia” began to take shape (Jääts Reference Jääts2000; Kalkun Reference Kalkun2014).

In 1945, right after the Second World War, the borders between Russian and Estonian Soviet Socialist Republics were redrawn, which subsequently split the Seto community between Estonia and Russia and eventually polarized them (Jääts Reference Jääts2000). Though the Estonian and Russian communities were oriented toward their respective governments and the church practices continued in separate languages, the cultural identity kept them together, particularly as border crossings were not an issue during the Soviet Union. The Setos in Estonia were still able to visit their families and perform religious rituals at Churches and at their ancestors’ cemeteries. Many Seto community members moved to cities (for example, Tallinn, Tartu, and Võru) and became part of the Estonian way of life. The social fabric of the Seto widened through media, books, and mixed marriages, and eventually the Seto language was limited to being used at homes yet not in everyday life (Jääts Reference Jääts2000). Helen Külvik, the head of the Seto Institute, observed that Seto youth who live in cities such as Tartu and Tallinn still tend to speak Estonian amongst each other in public rather than in Seto language (Külvik Reference Külvik2022).

After the fall of the Soviet Union, families were still able to cross the territorial boundaries to get in touch with their relatives, perform rituals at their elders’ graves, and continue their sociocultural activities. In the 1990s, the Setos who lived in the Seto municipalities were able to cross borders freely as the local authorities from both the Estonian and Russian sides of the border drew up a list of people who were local residents and permitted them to cross the border freely (BBC 2020). For example, Mariam (who went by her first name), a resident of Vinski village situated on the border between Estonia and Russia, moved from Petseri region in Russia to the Estonian side of the border in 1999 through the assistance of an Estonian government funded relocation program. In addition, in an interview she asserted the importance of Petseri (Pechory in Russian) as being part of a unified Seto land (Mariam Reference Mariam2021). However, in September 2000, Estonia’s aspiration to join the European Union put an end to this mutually agreed simplified border crossing between the two Seto communities divided by the territorial boundaries and essentially erecting a “Setu wall” (Berg Reference Berg2002).

Therefore, folklore and cultural traditions were instrumental in the assimilation of Setos into the mainstream Estonian cultural milieu, yet they were excluded as “backward people” because of their linguistic and religious traditions (Kalkun Reference Kalkun2014). The ethno-cultural revival of the Setos began in the 1990s. The new language policy of the restored Estonian nation did not help the Seto language (and the other Southern Estonian dialect Võru) to flourish, as it was not taught in schools (Maarja Reference Siiner2011). Through their unique folklore and Orthodox religious faith, the Setos identify themselves as an autochthonous ethnic community distinct from the rest of Estonia (Verschik Reference Verschik2005). Intellectuals and activists from the Seto community created the “Seto movement” to preserve their folklore and promote their language and tradition. Initiatives such as the Seto Congress, the Union of Setomaa Rural Municipalities, and the Seto Institute were established as a part of the Seto movement. Since 1994, the Seto Kingdom Day has taken place once a year to elect the representative of the Seto god – Peko – during which the community members and officials who represent various institutions of Seto Kingdom come together from both sides of the border (Berg Reference Berg2002). Each year, it takes place in different municipalities of the Seto region to elect their Chief Herald, ülembsootska. The Seto Kingdom has its own performatives – anthem, army, currency, cultural organizations, and a “border,” and during the Seto Kingdom Day visitors who do not wear Seto folk attire are permitted only with “Visas on arrival” (“seto kingdom” n.d.). For Rein Järvelill, a former chief herald of the Seto Kingdom, the idea of the Seto Kingdom Day is to create a stronger identity and boost self-confidence among the community members. Although the idea of having a kingdom, army, and currency is imaginary and symbolic, events such as this performatively bring Seto people together and unite them (Järvelill Reference Järvelill2022).

During the Kingdom day and their café day, commercialization of cultural aspects is vividly seen; the community members sell Seto costumes (see Figure 1), merchandise (t-shirts, cushion covers, etc.), Seto cuisine, and local alcohol (see Figure 2). By ways of commoditizing the culture, the community gains visibility in Estonia and abroad. Through commercial promotion of their differences, communities can affirm that their identity is not primitive or parochial (Cole Reference Cole2007). In addition, such tourism initiatives are supported by the EU funds, such as the Interreg V-A – Estonia-Latvia to promote “authentic experience” in ethno-cultural regions (European Commission 2019). As Callahan noted, traditional costumes, a form of visual cultural performance, “produce essentialised self-other relations” and therefore create identities and yet differences at the same time (Callahan Reference Callahan and Bleiker2018, 82).

Figure 1. Women from different generations adorned in Seto costume during café day event in Vinsky, a village on the border between Estonia and Russia in Southern Estonia.

Figure 2. Handsa, a traditional rye-based alcohol from Setoma and other food items on sale during café day.

The inclusion of the Seto language as a unique category in the Estonian census is still a contentious issue. The current Estonian census questionnaire excluded Seto as a separate category, rather it is considered to be a dialect of Võru language (Jääts Reference Jääts2015). Everyday practices in administration, education, and religious events in the Orthodox Church are in Estonian; therefore, preserving Seto language and Seto-ness is more of a community initiated identity construction process (Järvelill Reference Järvelill2022). The performative nature of leelo, a polyphonic singing tradition of Seto, is recognized by UNESCO as a “cornerstone of contemporary identity” (UNESCO 2009), and is another way in which the community keeps their identity protected. In Setomaa, leelo is performed, often, spontaneously to celebrate every occasion in life (Figure 3). The authenticity of such cultural representations through folk costume and singing is better conveyed to a wider audience through visual images and performances. As Bleiker puts it, such images in different cultural contexts “not only shape an individual’s perception but also larger, collective forms of consciousness” (Bleiker Reference Bleiker2018). Figure 3 exemplifies the performative aspect of how the Seto community promotes their cultural uniqueness even at an informal gathering of community members.

Figure 3. Members of the Seto community perform Leelo during a gathering at the gallery/performance space in Obinitsa.

During the 2021 municipal election, EKRE used the status quo in ratifying the 1920 Tartu Peace Treaty between Estonia and Russia – to their political gain (ERR 2021). The party’s motives were clearly witnessed during their election campaign; during a rally in Tartu, they displayed a symbolic border post between Estonia and Russia with a placard reading, “101 years old peace treaty between Russia and Estonia. We don’t need what is yours. Return what is ours!” (Figure 4). In Varsaka, where the seat of Setomaa rural municipality is located, EKRE placed a wreath under the monument for those who were killed in the Petsri region during the war of Estonian independence between 1918 and 1920, at the end of which the Tartu Treaty was signed (Figure 5). The nature of such political nuances is better studied through visual analysis, which Bleiker calls the “aesthetic turn” in politics: “Studying the politics of visuality involves understanding not only the role of images – still and moving ones – but also how visual artifacts and performances take on political significance” (Bleiker Reference Bleiker2019). In both aforementioned examples, the sentiment of EKRE parties is signified by means of using visual elements (i.e., signs and objects as signifiers).

Figure 4. EKRE party members with signs – “101 years old peace treaty between Russia and Estonia. We don’t need what is yours. Return what is ours!” – during the 2021 local municipal election rally in Tartu.

Figure 5. EKRE party placed a wreath at the monument in Varska commemorating the war of Estonian independence that took place between 1918 and 1920.

For the Seto community, both religion and culture are cornerstones of their identity. As Rein Järvelill explains, despite the administrative differences between the patriarchies of the Orthodox Churches on the Estonian and Russian sides of the border, for the Seto community there is no difference, as the sacraments are the same, regardless of the language (Järvelill Reference Järvelill2022). Furthermore, by partaking in cultural events – for example, the Finno-Ugric Congress and regular art initiatives at the Estonian National Museum (ERM) – the Setos promote their cultural singularity. The accession of leelo, traditional singing of the Setos, into UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity further strengthens their efforts to cement their identity.

Connecting the Three Dimensions

The three dimensions presented above give us a good chance not only to juxtapose but also to compare them with each other as elements of a chain of interconnected actors that instrumentalize Finno-Ugric identity through signification of discourses, aestheticization of policy practices, and performative engagements with the political sphere.

First, Finno-Ugric identity is differently instrumentalized by the Estonian state and EKRE. The Estonian government takes a rather depoliticized stance to the concept of Finno-Ugric world as a sphere of cultural projects that can be beneficial for unofficially appealing to kindred ethnic groups residing in Russia. EKRE adheres to a more politicized approach by accentuating cultural distinctions that sustain Estonia’s specificity irreducible to the unifying European normative discourse. At the same time, both EKRE and state institutions are interested in the amplification of the salience of Finno-Ugric civilizational discourse for national groups in Russia, which Moscow tries to downplay.

Second, when it comes to connections between national and local layers, they look quite ambiguous. The Seto community traditionally keeps a certain cultural distance from the central government, yet uses different opportunities – such as Congresses of Finno-Ugric Peoples and Finno-Ugric Capitals of Culture – for underscoring trans-national and cross-border components of their local identity. At the same time, the Seto community seems to be more interested in an open model of trans-border relations than the Estonian state, particularly after the restart of the Russian aggression against Ukraine. As for the national authorities, they seem to be more concerned about depopulation of Estonian localities and townships located at the border with Russia (Berg et al. Reference Berg, Sepp, Allik, Urmann and Vits2023), which constitutes a socioeconomic rather than a cultural problem.

Third, for EKRE, Setomaa is mostly an electoral resource, relevant for bringing up grievances related to the 1920 border treaty with the Soviet Union rather than acting as an important reference point in this party’s conservative political agenda. EKRE has never garnered a significant political following in the region, and at the same time, the issue of Seto identity is not salient for EKRE as a party stressing the unitary nature of the Estonian nation. For such a reason, the Seto people are not afforded the same level of agency as the Hungarians or Finns are.

Conclusions and Implications

In the concluding section, let us return to our main research question: how has the contemporary Finno-Ugric identity been instrumentalized and negotiated in Estonia? We strived to answer this question on three different levels: from the state, from ethno-nationalists, and from localities. Nevertheless, to arrive at this answer, we need to return to the three conceptual approaches introduced at the onset from the vantage point of these three specific cases that we have studied.

Let us start with floating signifiers. What we have found in our research is that the sociocultural construct of Finno-Ugric identity vacillates between many established reference points of the political discourse – between West, North, and East as geo-cultural categories; between the liberal ideology of protecting minorities and the electorally instrumentalized conservative archaisms; and between global appeals to universal norms of human rights and localized/inward-oriented forms of communal life. Our mixed methodological approach of comparing visualized representations of this Finno-Ugric identity with discursive contestations or justifications of its meaning has demonstrated the conceptual fluidity of Finno-Ugricness, as both the salience and centrality of this identity fluctuate depending on what role it comes to play in social and political logics.

When it comes to the sphere of aesthetics, we have seen that each of the signifiers produced its images and signs with their artistic and theatrical content generative of political dynamics. We have shown that there are tensions between politically neutral and sterile aesthetics of cultural festivities, and a plethora of politically explicit exposures of Finno-Ugric identity that may either boost Estonian cultural diplomacy and soft power, or put the Estonian government in a defensive position vis-à-vis some critical voices coming from Russia. Additionally, while some Finno-Ugric symbolism has been deployed in the ethnonationalist right, their aesthetic practices remain rooted in particularly Estonian visualities rather than broader Finno-Ugric ones. Nonetheless, the deployment of such aesthetic practices in each case runs in parallel with related rationales, whether depoliticizing and diplomatic, political and identitarian, or commercial.

As for performativity, this analysis offers a variety of genres in which Finno-Ugricness as a concept is manifested and enacted – dramatic accentuation of Estonian grass-roots “tribal” origins, creative dance and song shows, public speech acts, commemoration rituals, and festive commodification of local specificity and particularity. Those speaking on behalf of the Finno-Ugric community or as Finno-Ugrians, by reiterating, visualizing, and performing this Finno-Ugric identity, are processually refixing its meaning by providing it with a principal point of reference that, however, can make Finno-Ugric identity central and value-laden (as in the cases of the Estonian state and radical right) or marginal and value-neutral (as in the case of the Seto community). Nevertheless, each of these environs shares this reference to Finno-Ugric identity as some allusion to authenticity.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine that restarted on February 24, 2022, has shone a new light on our research. The war has elucidated the futility of Estonia’s multiple attempts to engage Putin in a mutually beneficial communication on cultural grounds that could skip politically divisive issues (Tambur Reference Tambur2021). Moreover, the Russian aggression did not unleash strong anti-war protests in any of the Finno-Ugric communities in regions of Russia, which means that no meaningful postcolonial solidarity with Ukraine was publicly articulated even among those ethnic groups that otherwise might consider themselves unduly oppressed by Moscow. Estonian Finno-Ugric activists – in particular, Oliver Loode – in March 2022 have publicly addressed kindred peoples in Russia with an appeal to jointly stand against the war that was qualified as a direct antithesis to the philosophy of the Finno-Ugric world (Loode Reference Loode2022). However, only a few individuals from Russophone Finno-Ugrians resonated with this statement and acknowledged a linkage between Russian war against Ukraine and Moscow’s colonial policies toward ethnically and linguistically non-Russian minorities within the country (Kovaliov Reference Kovaliov2022). One of these voices was Syreś Boläeń, who publicly appealed to all Finno-Ugric peoples to individually and collectively stand with Ukraine and resist Russian intervention by all possible means, including militarily (Syreś Reference Syreś2022).

In summer 2022, the URALIC Center, founded by Loode, published a “black list” of public figures of Finno-Ugric background who supported the war against Ukraine, which was aimed at banning them from further participation in international Finno Ugric movement and even probably from traveling to Europe (Berezhkov Reference Berezhkov2022). However, a complete break with Russia in the domain of ethno-cultural exchanges and contacts – including the cancellation of the already-issued tourist visas – has discontinued the operation of Estonian soft power toward kindred peoples living in Russia. Against this background, the war in Ukraine finalized and cemented the split within the international Finno Ugric community that began much earlier and that this study has elucidated. The border lockdown enforced by the Estonian government made it close to impossible for Estonian Finno-Ugric activists to sustain contacts with those kindred groups in Russia who disagree with the Russian policy of self-isolation and who appreciate trans-border connectivity (Region Expert 2021).

In the same vein, the recent visa ban imposed for Russian citizens visiting the EU would prevent Setos from Pechory region in Russia visiting their family members and attend religious ceremonies on the Estonian side. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, travel restrictions have limited the frequent movements of the Seto community members on either side of the border. Setos often visit the Orthodox monastery in Pechory, an important religious site for the community, and have also frequented the town for shopping. Though the recent visa ban may limit travel, as one of the community members put it in an oral interview, the political decision made by the Estonian state in response to Russia’s war on Ukraine outweighs the travel concerns faced by a significantly smaller number of Setos living on the Russian side of the border and has equivalized the Seto community on that side of the border – as well as all Finno-Ugric peoples within Russia – with the Russian body politic more widely.

This article has demonstrated that, even in the bounded context of Estonia, the concept of Finno-Ugric civilization and cultural identity is multifaceted and kaleidoscopic rather than unitary and clearly delimited. Such insights can be equally applied to the deployment of Finno-Ugric identity in other countries belonging to this community, such as Finland or Hungary, or amongst the Finno-Ugric republics and regions of the Russian Federation. Outside of the Finno-Ugric world, these discoveries and logics can be expanded to civilizational discourses more broadly. We have seen that reference to civilization is instrumental in that it serves to synchronically fix the meanings that relationally situates values, ethics, and images to peoples and spaces. It is through these performances and demands that such interlocutors constitute their own identities and civilizational communities by temporarily and provisionally fixing such meanings. In this way, it is possible to speak of Finno-Ugric civilizations and of civilizations in the plural, extending such an understanding to Wests, to Ummahs, and to Eurasias.

Disclosure

None.