No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 May 2021

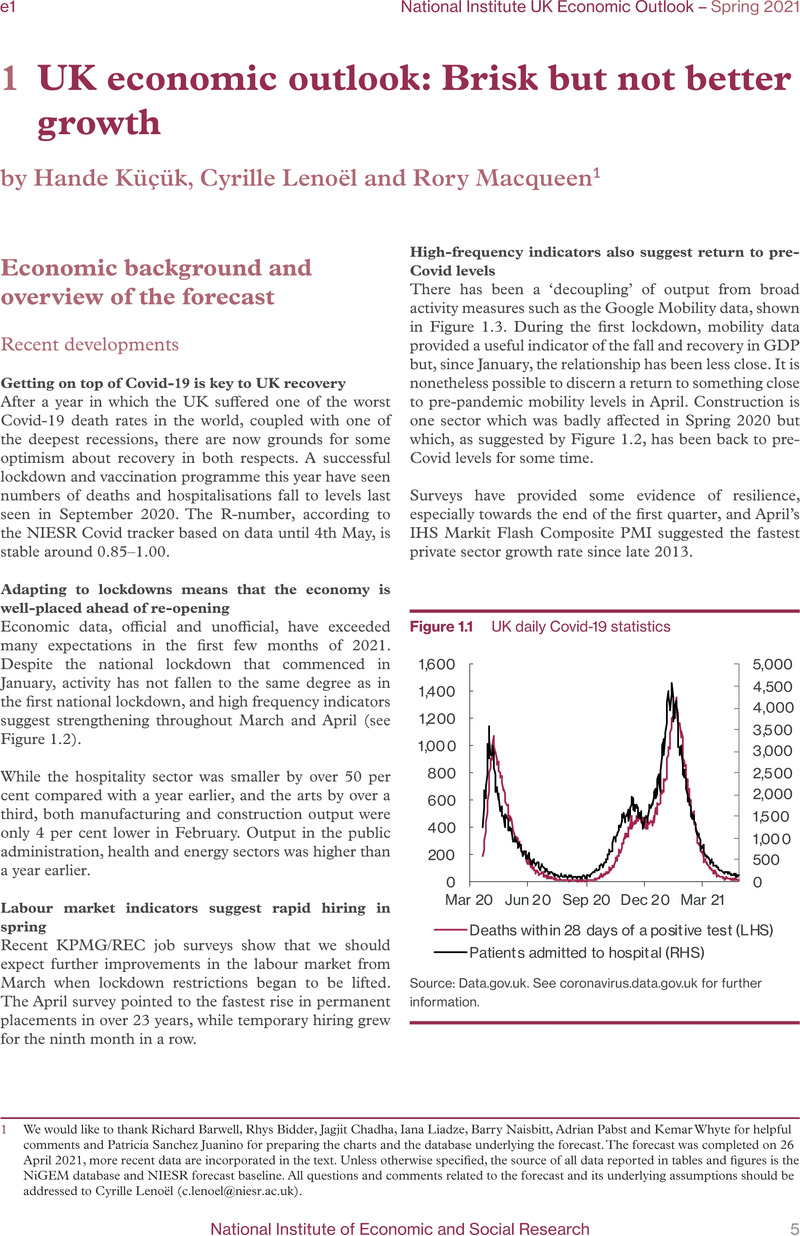

We would like to thank Richard Barwell, Rhys Bidder, Jagjit Chadha, Iana Liadze, Barry Naisbitt, Adrian Pabst and Kemar Whyte for helpful comments and Patricia Sanchez Juanino for preparing the charts and the database underlying the forecast. The forecast was completed on 26 April 2021, more recent data are incorporated in the text. Unless otherwise specified, the source of all data reported in tables and figures is the NiGEM database and NIESR forecast baseline. All questions and comments related to the forecast and its underlying assumptions should be addressed to Cyrille Lenoël ([email protected]).