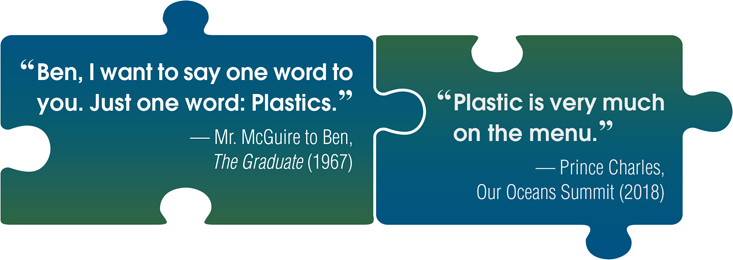

The Graduate was already an iconic movie by the time I started my graduate studies. It was always double-billed-screened with Harold and Maude on every graduation weekend! The word ‘plastics’ was immortalized and remained etched on one’s psyche. Today, we find ourselves in the next millennium, and the chance of finding plastic particles in our seafood is very high, prompting Prince Charles’ comment, and yes, plastic is everywhere like Mr. McGuire predicted, without full implications!

Between 1 and 2 million tons of plastic are entering our oceans each year. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, located between Hawaii and California, is estimated to contain more than 1.5 trillion pieces of floating plastic over an area estimated to be more than 1.5 million square kilometers. If not removed quickly, these plastics will break down into microparticles under the sun and other environmental factors, enter (or might have already done so) the marine life, and ultimately find their way into our food. Collaborative efforts between San Francisco and Rotterdam are already under way to remove these pieces. A 2000-foot cleanup contraption, known as Wilson, created by Boyan Slat, a Dutch entrepreneur, was launched in September 2018 for a yearlong series of tests. However, it was reported that Wilson was being towed back to San Francisco during the first week of January 2019 for repairs. While these sporadic efforts will continue, it’s important to address this problem at its core.

Two articles in this EQ edition, without specific intent, have ocean(s) as their underlying context, and it is important to peruse them from this vantage point. On one hand, oceans are being substantially polluted with plastics (among other things), and on the other, we are losing the polar ice caps at an alarming rate due to climate change. Both can be reversed by spreading increased awareness and taking immediate tactical and strategic steps. Materials scientists will play a key role in these.

Approaches for reversing plastics pollution can be twofold. First, materials scientists could contribute to eliminating the streams of plastic that are entering the oceans by developing more effective plastic depolymerizing avenues for all plastic waste. Second, there needs to a substantial increase in research efforts in developing economically advantageous biodegradable polymers and plastics at an accelerated pace; this is crucial in maintaining the long-term health of the marine ecology and our agricultural sustainability.

Evidence-based scholarly articles indicate that melting polar ice caps will accelerate the melting of seabed permafrost. Though recent studies indicate that “ancient carbon” from methane hydrates in the permafrost is being released very slowly, the seabed permafrost melting could compound climate change substantially in the future.

A consistent message is coming through: Life-cycle considerations of all future materials development and implementation activities (that further the circular economy without increasing our carbon footprint) will be key to the sustainability of our world.