Introduction

Takoua Ben Mohamed started making comics to communicate with children and teachers at school. Born in the oasis of Douz (South Tunisia), she was eight when she arrived in Rome, the city where her family found refuge from the oppressive Ben Ali regime in the 1990s. Takoua turned shy and taciturn in a classroom of multilingual pupils schooled in Italian. Comics enabled her to make contact with people, establish empathy, raise questions, and exchange Arabic and Italian words with classmates, neighbours, readers and audiences across the world (Ben Mohamed Reference Ben Mohamed2018, 189). Stemming from an urgent need to reply to pressing questions on the hijab, contest islamophobia, and visualise trajectories marginalised by nationalist regimes of citizenship and migration in the Mediterranean, her stories have experimented with different genres and formats of comics, from graphic journalism to graphic memoir, and across digital and printed media. This article considers Ben Mohamed as a cultural translator and producer of Italian culture within the globalising flows that make comics an increasingly significant transcultural medium.

My analysis engages with a set of compelling questions around comics and transculturality, and comics and Italian mobility. For example: why are comics an increasingly popular medium of narration for individual and collective stories that straddle languages and cultures? Which type of cognitive and narrative processes are exposed in this expanding production? Is the recent global proliferation of comics apparent also in the Italian transnational context? And how might this challenge the established – notably, academic – perceptions of location, homogeneity, and canon of Italian culture? By seeking to answer these questions, this article addresses multiple fields of scholarship concerned with transcultural mobility, notably Italian Studies, Memory Studies and Translation Studies. It also addresses the emerging, predominantly anglophone, scholarly field of Comics Studies, with its global reach and rapidly establishing canons, models and critical tools.

Recent scholarship on postcolonial comics has just begun to tackle the linguistic and cultural tensions within different comics scenes, questioning the social as well as the cultural dimensions of the mobility of comics authors and their work (Mehta and Mukherji Reference Mehta and Mukherji2015). By focusing on the comics of a Tunisian author from Rome, my study engages with the theoretical and methodological framework of a large research project which explores Italian culture through the multiple forms of its mobility. The Transnationalizing Modern Languages (TML) research project foregrounds translation – in its interconnected linguistic and cultural dimensions – as a central component of the mobility and production of (Italian) culture. By foregrounding historical dimensions such as colonialism, post-colonialism and decoloniality, and by repositioning migration and diasporic communities as direct contributors to the formation of Italian culture, the TML project questions notions of canonicity, homogeneity, and authenticity, whether they are applied to literature, film, or any other form of cultural expression (Burdett, Havely and Polezzi, Reference Burdett, Havely and Polezziin press).

This article engages with the transnational and translational framework of the TML project by exploring specifically the productive nature of memory and translation in contemporary processes of identification. It does so by considering the linguistic and cultural dimensions of Takoua Ben Mohamed's production, which encompasses multiple genres and formats of comics: from the graphic journalism of Il fumetto intercultura (Intercultural Comics, her digital platform and graphic blog), via the book-length project Sotto il velo (Reference Ben Mohamed2016), to the more recent graphic memoir La rivoluzione dei gelsomini (Reference Ben Mohamed2018). All these comics are multilingual and expose the translational nature of memory. Through an examination of the specific challenges and strategies developed by Ben Mohamed as a comics author and cultural translator, the article explores the potential of comics as a transcultural medium.

Memory and translation are constitutive and interrelated processes of transcultural mobility. Memory is a creative process that connects past, present and future, shaping processes of (self-)identification and ideas of belonging. Memory is an essential component of culture, and changes with time and sociocultural context. One way to understand this change is to look at how memory ‘travels’ through a series of mental, medial and social processes (Erll Reference Erll2011). For example, this can entail looking at how certain forms of memory – written records, say, such as fieldwork notes or letters, photographs, artworks, recorded interviews, but also the immaterial, sensorial memories of an individual – may ‘travel’ into a medium, in this case a comic book, engaging the cognitive and narrative process – the practices of (self)identification – of new potential carriers of the memory. Scholars in Memory Studies have described this movement as an incessant process of mediation and remediation of memory content (Erll and Rigney Reference Erll and Rigney2009; Erll Reference Erll2017) which in a mobile and multilingual world is not only similar to, but – as I argue – intertwined with translation. Mnemonic processes increasingly unfold not only across, but also beyond cultures (Erll Reference Erll2011), showing incessant transcultural dynamism which challenges and transcends the notions of self-contained, homogeneous, isomorphic culture (Welsch Reference Welsch, Featherstone and Lash1999). This article adopts a translational lens to acknowledge, firstly, the linguistic and cultural tensions of the forms of mediation, remediation, rewriting and transformation of memory across and beyond cultures, and secondly, to acknowledge the productive nature of these complex transcultural processes, which testify to what Loredana Polezzi calls ‘the translational fabric of cultural practice (and also of everyday life)’ (Polezzi, Reference Polezziin press). Whilst addressing a gap in scholarship about Ben Mohamed specifically, this article points out the increasing relevance of comics for the study of memory, translation and transculturality.

The first part of the article introduces the transnational Italian comics scene in the light of the proliferation of transcultural comics as media of communication and self-translation in a mobile and multilingual world. The analysis then focuses on the graphic journalism of Takoua Ben Mohamed in order to explore the social and cultural dimensions of her work and how they are expressed through the different formats and the multiple translational strategies of her multilingual comics. The last section turns more specifically on the increasing relevance of comics as media of transcultural memory, focusing on La rivoluzione dei gelsomini (Ben Mohamed Reference Ben Mohamed2018) a graphic memoir which exposes critical questions on the representation of the histories of Italy and Tunisia.

Twenty-first-century comics across and beyond languages and cultures

Over recent decades, research on Anglophone comics and the Francophone bande dessinée has engaged with the relevance of comics as a cultural medium and object of study (Baetens and Frey Reference Baetens and Frey2015). The transcultural mobility of the medium since its inception in the nineteenth century – for example the mixing of artistic form and cultural content across the Franco-Belgian bande dessinée, manga from Japan, fumetti from Italy, or comics from the US – is widely acknowledged and has been explored from a variety of scholarly perspectives. An expanding body of scholarship adopts a postcolonial lens to trace the circulation of authors of African descent within globalising comics industries, foregrounding the role of these artists in the global popularity of comics and in the mobility of genres and themes (Mehta and Mukherji Reference Mehta and Mukherji2015; Denson, Meyer and Stein Reference Denson, Meyer and Stein2013; Repetti Reference Repetti2007), as well as in the rewriting of national histories to respond to the colonial system, at the same time highlighting the interconnected circuits and hybridity of arts and histories (Bragard Reference Bragard2016 333). Whilst memory and mobility emerge as central themes in the production of comics in the twenty-first century, the flexibility – and translational potential – of a medium that combines words and images have been taken in new directions by authors of stories that straddle languages and cultures, such Marjane Satrapi and Shaun Tan. With no background in comics or in any specific comics tradition (Root and Satrapi Reference Root and Satrapi2007) these authors have pushed the cultural, formal and creative borders of the medium to represent their stories. Whilst Persepolis (Satrapi Reference Satrapi2007) has established the graphic memoir as a medium for the representation of individual and collective histories in the twenty-first century, the silent comics of Shaun Tan are unique in visualising the experience of cultural miscommunication and bewilderment as much as the human ability to draw sense from a puzzle and use the imagination (Earle and Tan Reference Earle and Tan2016). The comics of Satrapi and Tan have engaged audiences across the world and inspired new generations of comics authors.

Comics such as Persepolis (Satrapi Reference Satrapi2007) and The Arrival (Tan Reference Tan2007) expose important changes in the mobility of memory and history in our times and are well situated to express their transcultural and translational tensions. This is, firstly, because they enable acts of mediation and translation of scattered, fragmented, unwritten, multilingual, variably recorded memories. The multimodal communication enabled by comics conveys both the multidimensional (i.e. multisensorial, affective) nature of mnemonic processes and the variety of ways of remembering within culture. As a number of scholars have pointed out, comics facilitate non-linear representations of time that resonate with the mnemonic processes of authors and readers. Comics are ‘well suited to the task of conveying subjective time, since many of its formal features follow patterns that reflect the way memory itself works’ (El Refaie Reference El Refaie2012, 281) and they provide a ‘format that offers effective ways to deal with the uncertainty and disorder inherent in life stories’ (McNicol Reference McNicol2018, 279). Even more importantly, ‘in comics reading can happen in all directions: this open-endedness, and attention to choice in how one interacts with the pages, is part of the appeal of comics narrative’ (Chute Reference Chute2017, 25). In other words, comics engage readers in complex processes of meaning-making, opening multiple paths of mediation and translation of their content: Shaun Tan for example considers the readers of his work as ‘co-creators, needing to invest meaning into illustrative stories that are really half-finished, deliberately incomplete’ (Earle and Tan Reference Earle and Tan2016, 391). Memory and history need the intellectual and imaginative investments of people who would identify with their incomplete narratives and engage in translational practices that change with social and cultural configurations. In a mobile and multilingual world, comics provide a flexible medium for the transcultural mobility of memories, subjectivities and cultures.

As I argue also elsewhere, the Italian comics scene thrives in multiple, transnational directions, (Spadaro Reference Spadaro, Burdett, Polezzi and Santelloin press), demonstrating that Italian culture is produced inside and outside Italy, in many languages and by people of increasingly different backgrounds. In recent years, some of the most innovative authors have visualised stories of migration, of the mobility of borders, of transnational and translational trajectories marginalised by mainstream narratives of Italian history and culture. By reclaiming family histories of exile, migration and displacement and by translating their memories into comics, an increasing number of comics authors are contributing to a broader, more inclusive picture of modern Italian history. Palacinche: Storia di un'esule fiumana (Sansone and Tota Reference Sansone and Tota2012) for example, is a recent, innovative comic book that sheds light on the mobility of the borders of Italy as a nation state as well as on the transnational dimension of the Italian comics scene. In Palacinche, Caterina Sansone and Alessandro Tota have combined their creative and narrative practices – notably comics and photography – to translate their family memories and their own experiences as Italian artists navigating the transnational circuits of the cultural industries. The success of the book and its translation into French and German is one example of the thriving Italian comics scene in Paris, where artists such as Igort, Tota and Manuele Fior have been making, translating and publishing some of the most innovative comics of the last few decades (Orsini Reference Orsini2014). More recently, Pia Valentini's award-winning graphic novel Ferriera (Reference Valentinis2017) has explored marginalised trajectories of labour and migration between Italy, Europe and Australia, while Papaya Salad, by the Italo-Thai Elisa Macellari (Reference Macellari2018), and the two volumes by Ciaj Rocchi and Matteo Demonte (Reference Rocchi and Demonte2015, Reference Rocchi and Demonte2017) visualise the transnational histories of families of Asian, Chinese and Italian background in Italy throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Within an expanding variety of trajectories and styles, all these comics straddle languages and cultures and expose tensions between individual and collective histories, memories and mobilities. This expanding production highlights the dynamism of the ‘Italian’ fumetto at formal and thematic level, the transnational and multilingual nature of its scene, and the increasingly diverse background of new authors – notably an increasing number of women – who navigate globalising cultural industries. In this arena, published books are just one of the possible formats of comics, and the graphic novel only the most recent – and commercially successful – genre, as webcomics and new self-publishing ventures transform the traditional practices, circuits and consumption of fumetti. These transformations expand the picture of the underground vs mainstream comics scene with which many Italian comics authors and scholars have typically been identified (Pavan Reference Pavan2014) and reflect the development of the Italian comics scene (Various authors 2016). Takoua Ben Mohamed's trajectory as a comics author and media professional illuminates some of the new directions of the Italian fumetto across genres and media. She represents those young, urban and networked generations that every day produce and share millions of digital images as forms of self-narration (Mirzoeff Reference Mirzoeff2015), posting her comics on social media and trying different forms of publication, whilst developing her skills as a media professional and pursuing her studies in animation. Her graphic narratives have taken a variety of forms: cartoons and short stories, exhibitions, blog a fumetti (comics blogs), and comics books such as Sotto il velo (2016) and La rivoluzione dei gelsomini (2018). Through all these projects Ben Mohamed has been developing her own style of visual storytelling and a distinctive profile as a media professional and social media influencer, having little or no contact with existing comics circles in Italy or Tunisia, despite some of the former – notably the thriving comix underground scene – having important hubs in the same area where Ben Mohamed grew up, the eastern periphery of Rome. Ben Mohamed's work has stemmed more from the urge to communicate the experience of living between cultures and to contest Islamophobic representations in the Italian mainstream media, than to establish herself as a comics artist (Interview with the author, Reference Ben Mohamed2015). Her comics production is grounded more in the US (Matt Groening's The Simpsons) and Japanese manga TV series screened on Italian commercial television than in the longstanding traditions of the Italian fumetto, Tunisian satirical cartoons or the Franco-Belgian bande-dessinée, which were all equally distant from her social and cultural environments in Italy and Tunisia, and to which her work has only recently been introduced. Because she considers her work to be concerned more with social and humanitarian issues than with developing formal or aesthetic aspects of comics, Ben Mohamed identifies herself as a journalist rather than a comics artist.

The graphic journalism of Takoua Ben Mohamed

Takoua Ben Mohamed was just 14 when, participating in a community event in the Centocelle Mosque in Rome, she started producing manga-style vignettes and comics on the experiences of Muslim women wearing the hijab in Italy. This was the beginning of her first project, Il fumetto intercultura: il graphic journalism secondo Takoua Ben Mohamed, which continues to this day. First shared at community events and on Facebook, these comics have been openly accessible online since 2016.Footnote 1 As a series of small exhibitions and workshops in intercultural education, the project travels inside and outside Italy via circuits of cultural activists, academics and journalists, well beyond the Muslim community networks and the mass media for Muslim audiences (such as the global Indonesian TV channel Trans7) that first disseminated it. In Italy, Il fumetto intercultura has been circulating through school and library networks with the support of humanitarian associations, local councils, national institutions and corporate ventures, which often invite Ben Mohamed to speak at public events and receive prizes in acknowledgement of the social and cultural relevance of her work. These are important achievements for Ben Mohamed, who considers herself a journalist and media professional concerned with social rather than religious or theological – notably Islamic – themes. Her comics tackle social and cultural issues such as prejudice, racism, bullying and sexism, featuring the experience of a female character in hijab, a personaggino which allows her to explore – as we will see – a series of processes of (self-) identification.

These comics tackle the racist and cultural stereotypes projected onto young people of non-European backgrounds in Italy, providing material for discussion with students, teachers and the general public. Some of the early comics for example are entitled ‘Pregiudizi? Razzismo? No Grazie! (‘Prejudices? Racism? No, thanks!’) and ‘Rom’ (‘Romany’). These stories feature characters of Chinese, Rom and African origins, placing the experience of the Muslim communities in Italy within the wider context of social, cultural and religious tensions around ideas of Italian citizenship and belonging. These stories are also examples of the author's longstanding activism in the struggle for the reform of Italian citizenship, which over the last decade has rallied people of multiple backgrounds and generations (Colucci Reference Colucci2018). Il fumetto intercultura foregrounds the questions of identity and cultural identification of contemporary Italy's so-called seconde generazioni (second generations, a neologism which encompasses the offspring of migrants, whether born or only raised in Italy). For example, ‘Chi sono io? Un ponte tra culture’ (‘Who am I? A bridge between cultures’)Footnote 2 visualises the thoughts of a girl who finds herself labelled as an Italian when she is in Tunisia, and as a Tunisian when in Italy. While reflecting questions shared among young people growing up between different cultures, Il fumetto intercultura records, acknowledges and disseminates the specific experience of Muslim women and youth along with many other Italians of non-European backgrounds. My argument is that by translating these experiences into comics, Ben Mohamed has opened new spaces for the expression and sharing of these memories.

I would argue that the development of the project tracks changes in the self-perception of young Muslims in Italy after the 2011 Arab revolutions in North Africa and the Middle East (Acocella, Pepicelli and Cigliuti Reference Acocella, Pepicelli and Cigliuti2015; Pepicelli Reference Pepicelli2012) and parallel shifts in Italian imaginaries about the Islamic world (Burdett Reference Burdett2016). ‘Le domande più assurde sul velo’ (‘The most absurd questions about the veil’) is a narrative theme that Ben Mohamed has drawn in different versions, for example as a vignette (Figure 1), as well as a short story available on the online platform of the project.Footnote 3

Figure 1. Le domande più assurde sul velo. (Courtesy of Takoua Ben Mohamed).

In both versions, the story aims to convey the variety and complexity of the feelings of Muslim women in hijab when confronted with a barrage of questions. These comics visualise the experience of being the object of projections, prejudices, and sometimes just the naïve curiosity of non-Muslims towards Islamic culture. In the vignette, a series of mundane questions are thrown from all directions and rapidly fill the space above and around the girl in hijab, or rather a three-headed, metamorphic character that visualises the complex feelings raised by these constant interrogations. By emphasising the girl's exasperation and the strength required to resist the overwhelming flood of questions, this version of the story conveys feelings of resistance and defensiveness in an environment charged with explosive tensions, whereas the extended, later version of the same story features a possible alternative. In this second comic, the series of questions ends with a simple, albeit crucial one: ‘Why do you wear the hijab anyway?’ By addressing the individual choice of the girl to wear the hijab, this question lights up her eyes and opens up the possibility of an honest dialogue between individuals.

Since its inception, Il fumetto intercultura has wielded comics as tools for self-awareness and communication for Muslim and non-Muslim audiences. The playful emphasis and the visual metaphors of the comics framework enable a representation that is at once immediate and multi-layered. The multimodality of the medium conveys the verbal and non-verbal dimensions of communication, translating the full complexity of the linguistic and cultural exchange. Comics allow readers to visualise body language and unspoken words beyond the written dialogues, whilst the lettering of the captions and the bubbles conveys the emotion in the voices and thoughts of the characters. The manga style and the positive irony distinctive of Ben Mohamed's work produce a liberating and disarming effect that allows people to identify with the characters in the comics and reflect on their own transcultural experiences.

Memory and language: the translational dimension of comics

Ben Mohamed's visual style is driven by a constant search for immediacy to facilitate empathy and the identification of the reader with the characters in her stories. At the same time, her production is characterised by a continuous tension in the process of identification of the author with the protagonist of most of the stories, the female personaggino in hijab who explores the clashes and contradictions of her multiple belongings (Spadaro Reference Spadaro2016). Whilst the early comics from the community events translate the memories and experiences of Muslims in the West, other projects have progressively enabled the emergence of Ben Mohamed's self, revealing her positioning, her questioning and feelings towards different aspects of the cultures in her background. This process of (self-)identification is manifested in the use of languages and memories in the comics, and shows the productive and intertwined nature of memory and translation.

In the bus stop [sic], one of the early stories of Il fumetto intercultura,Footnote 4 sets out to represent an episode of linguaphobia that would potentially be familiar to any Muslim woman. Two women in hijab speak Arabic at a bus stop and become the object of a series of speculative and racist comments from two white men. The latter are blind to the fact that despite the Muslim outfits, the women may, in fact, speak and understand their language all too well. At the end of the story it is revealed that they do, causing great embarrassment to the male characters. To emphasise the universal nature of this experience for Muslim women, Ben Mohamed has put the dialogue between the two female characters in Modern Standard Arabic rather than in the dialects actually spoken in everyday life – such as the Moroccan of the women who reported the episode to her or the Tunisian that she speaks (Interview with the author, Reference Ben Mohamed2015). In this comic, the Modern Standard Arabic translates the experience of two specific women into a story that may be shared regardless of nationality or background by any Muslim woman, and thanks to the immediacy of the comic medium, also with non-Arabic readers who may embrace this story as their own. It would be possible to see this process as an example of remediation of memory content (Erll and Rigney Reference Erll and Rigney2009); yet to acknowledge the full complexity of a multimodal process enabled by the visual and written devices of a multilingual comic, we should consider its translational dimension. In the bus stop shows the intertwining of memory and translation in the creative and narrative processes of the author to engage her readers, and is an example of the expanding modes of translation which, as Loredana Polezzi has put it, ‘are articulated along a continuum of practices – a translation continuum which is constitutive of our mobile and multilingual world’ (Polezzi Reference Polezziin press). The making of comics as tool of communication and self-narration across and beyond languages and cultures is part of this multimodal continuum.

Ben Mohamed's multilingual comics feature the variety of her linguistic and cultural repertoire, which includes translanguaging with broken English and French, vernacular Roman and Tunisian dialect, as well as references to a variety of global pop (sub)cultures of her generation. The relevance of these linguistic and cultural elements for her production is apparent in all her projects, including the graphic blog Ricciocapriccio – Il fumetto intercultura, and the subsequent book Sotto il velo, published by Beccogiallo in 2016. These works show the progressive process of identification of Ben Mohamed with the personaggino in hijab of the early stories. Whilst the Arabic language of In the bus stop was meant to encompass the experience of any Muslim woman in Europe regardless of nationality or background, the Roman slang featured in later stories identifies the author, as she puts it, as a tunisina de’ Roma (in Roman vernacular, a Tunisian from Rome).

The comics blog Ricciocapriccio – Il fumetto intercultura was Ben Mohamed's first professional undertaking as a comic artist and a blogger. Ricciocapriccio is a trendy hair salon and cultural hub in central Rome. Many of the salon's clients are educated media professionals and academics, and the salon regularly hosts book launches and cultural events, while the website features a number of blogs on topics such as fashion, love, sex, transgender, literature and media. This is a very different space from the Muslim community centres and schools where Ben Mohamed shared her early comics. This sleek, sophisticated hair salon represents a space of encounter between the author and fashion and media industry professionals, who commissioned her first publishing project – the comics blog for Ricciocapriccio's website – and contributed to the development of new themes and forms of representation of women's bodies in her work. As Ben Mohamed has put it (interview with the author, Reference Ben Mohamed2015), by making comics for this project she has begun to appreciate the effectiveness of themes such as beauty, fashion, women's health and wellbeing in contesting cultural and racist stereotypes. In other words, this project has influenced her development as a comics author and media professional at a number of levels. The encounter between Ben Mohamed and Ricciocapriccio stemmed from a 2016 initiative by Renata Pepicelli, who organised a cultural event on hair and the hijab with Ben Mohamed and clients of the Ricciocapriccio salon, to challenge the stereotypes about Muslim women in Italy. The success of the initiative led to the commissioning of a comics blog for the salon's website and social media profile.

By featuring everyday negotiations of fashion and make-up trends, the Ricciocapriccio vignettes aim to change the representation of Muslim women to non-Muslim audiences and to facilitate processes of identification between people of different backgrounds. The irony and playfulness of Ben Mohamed's trademark style enable a fresh approach to topics made sensitive by the political and cultural tensions around Muslim women's bodies in Europe. The narrative and aesthetic repertoire of the blog encompasses pop culture icons familiar to Italian readers – such as H. R. Geiger / Ridley Scott's Alien and Matt Groening's Marge Simpson – and styles of Islamic fashion of which non-Muslim audiences would be much less aware (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hair style. (Courtesy of Takoua Ben Mohamed.)

By featuring such characters as an Islamic fashion blogger and a follower of YouTube hijab tutorials, these comics translate and raise awareness of important threads in the cultural and aesthetic imagination of Muslim women in Italy. At the same time, the stories show the complex individual negotiations of fashion models and the social pressure regarding women's bodies, inviting identification from readers of any background. Representing anxieties and eating disorders, some cartoons openly show the frustrations and subversions generated by transcultural forms of gender normativity that intersect the quest for self-determination of the personaggino.

Through this blog, the representation of the personaggino's body takes new and unexpected directions, for example in ‘Le mie cose’ (a colloquial expression for ‘my period’). By explicitly representing menstrual pain, this comic challenges representations of women's bodies, blood and the menstrual cycle that are subjected to the regulation and regimes of visibility in religious cultures – whether Muslim, Christian, Jewish or other. Both the topic and the vernacular language of this cartoon show the progressive identification of the author with the personaggino, a process which has entailed a considerable challenge for Ben Mohamed, for example when she started to draw the personaggino unveiled. As she put it in an interview with me in 2016, during the making of her book, ‘the personaggino…she may well be me, or maybe not’. This constant tension firstly highlights the experimental nature of the translational process behind the making of her comics as she keeps drawing from interviews as well as from personal memories. Secondly, it shows Ben Mohamed's awareness of the risk of being stereotyped, or taken as a representative, of Muslim women in hijab, which she is determined to avoid. Her work aims to question and contest homogenising representations of ‘Muslim’ or ‘Italian’ culture by playing with their internal and external stereotypes and showing the process of their reinvention and recombination. As the stories began to translate more explicitly her own memories, language – notably the dialect of Rome and its colloquial expressions – has become a major device in the process.

Sotto il velo – di una tunisina di Roma

Sotto il velo, Ben Mohamed's first comic book, features ‘la mia vita con il velo per le strade di Roma’ (my life with the hijab in the streets of Rome), expanding on the vignettes of the blog to develop a coherent narrative structure organised in short episodes of 3–5 pages each. The book features the protagonist's search for self-determination through a series of everyday situations common to any young woman of her age, such as shopping and interactions with neighbours, potential employers and people in the urban landscape. By going out in the street with her hijab, the young woman experiences judgements and unwanted comments from a variety of people, including religious fundamentalists, white secular men, and women of various social and ideological backgrounds. Ben Mohamed's manga style plays on – and challenges – stereotypical representations of Islamic fundamentalists (bearded, wearing kaftans, or in black from head to toe), radical Westerners (white, blond and male), or provocative pin-ups. Beyond these cartoon characters, the background of the panels is filled with crowds of anonymous and evil-eyed figures with strings of ‘BLABLABLA’ emanating from their large mouths. Developed as a narrative device for a book-length project, these recurrent figures in the background translate the memories of unwanted gazes and comments and represent an example of Ben Mohamed's ability to make use of the multimodal language of comics within the simple narrative structure and style of this book. The caricatural devices of the comics medium allow an underlining of the emotions (such as desire, curiosity, frustration) that drive the everyday encounters represented in the stories. The self-reflective attitude adopted by the protagonist throughout the book highlights the relational nature of the processes of identification that combine linguistic and cultural tensions, mutual stereotypes, emotions and memories. This is an early and recurrent theme in Ben Mohamed's work, and informs the way in which she translates the experience of living between cultures: a series of encounters, clashes and mutual reflections that challenge exclusive ideas of cultural and national belonging for Muslims and non-Muslims, Italians and Tunisians, and in so doing raise awareness of the performative, transcultural nature of processes of (self)identification.

Sotto il velo is constructed as a fictional autobiography in which Ben Mohamed represents her own prejudices, desires, disappointments, and scleri (emotional turmoil) as they are called in Rome. The informal nature of comics allows Ben Mohamed to introduce an element that she considers important in the self-perception of Muslims of her generation in Italy, namely their accents and slang, which track their rootedness in the specific urban and regional contexts of their upbringing (Ben Mohamed, interview with the author Reference Ben Mohamed2015). Sotto il velo features the spoken language of the author and the vernacular expressions that identify her as a tunisina de’ Roma and a Muslim woman sensitive to global issues such as the burkini controversy, the rise of Isis, and Islamophobia. The book stems from Ben Mohamed's urge to visualise through an accessible medium the experience of being a young Muslim woman in Italy. It does so by explicitly foregrounding her memories, emotions and languages, in tension with ideas of a collective, indefinite Muslim self. This represents a further step in the development of the creative and narrative strategies of the author and contrasts with the Italian fantasies of Mussulmania which, as Ben Mohamed explains, is a recurrent Italian expression identifying an imaginary Muslim country that exists in the mind of many of her interlocutors in Italy (Ben Mohamed, interview with the author Reference Ben Mohamed2016). In Ben Mohamed's understanding, Mussulmania conveys the common clichés about Muslims in Italy, encompassing all Arab countries in a stereotyped version of Saudi Arabia and conflating all Muslim people into one ethnicity localised somewhere around North Africa and the Middle East. By representing this racist idea in her comics, Ben Mohamed aims to counter its effects – specifically, to raise awareness of the sheer diversity of Muslim cultures across the world, of the relative weight of Arab culture within it, and of the lives and struggles of young people who in their Italian home towns are still labelled by their neighbours as immigrati (immigrants) and foreigners.

In Sotto il velo, the indefinite personaggino in hijab becomes Takoua, a tunisina de’ Roma who in the episode entitled ‘Black fashion style (ma non per tutti)’ (‘Black fashion style – (not for everybody though)’) uses a couple of very Roman expressions such as ‘Aoo – paro una de l'Isis!’ (‘Hey – I look like I belong to Isis!’) to expose and subvert the pervasiveness of representations of young Muslims as foreign fighters in Syria. The translanguaging with English in the titles references the global circuits of fashion, mirroring – indeed ironically reversing – the global circulation of images of Isis fighters. As these elements short-circuit into the subjectivity of the author, they provoke an eruption of Roman slang and facial expression (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Black fashion style (ma non per tutti). (Sotto il velo, courtesy of Takoua Ben Mohamed and Edizioni BeccoGiallo, Italy)

Figure 4. Black fashion style (ma non per tutti). (Sotto il velo, courtesy of Takoua Ben Mohamed and Edizioni BeccoGiallo, Italy)

Whilst explicitly drawing on the personal experiences of the author, Sotto il velo captures key details of the trajectories of (Muslim) women of Ben Mohamed's generation as they confront the intersecting challenges of gender, religious, cultural and linguistic heteronormativity. The book represents different aspects of young women's struggle for independence and self-determination – for example, how they access a job market which privileges single, childless, physically attractive, flexible workers with no apparent religious affiliations. These aspects are foregrounded in the episode ‘Colloquio – lo sclero di ogni donna’ (‘Job interview – the emotional turmoil of every woman’) as the book underscores important and recurrent themes in Ben Mohamed's production – namely the value of education, motivation and intellectual development in the author's personal and professional trajectory.

La rivoluzione dei gelsomini

La rivoluzione dei gelsomini is a graphic memoir that traces the transnational trajectory of the Ben Mohamed family from the years of the Ben Ali regime in Tunisia to their present lives in Italy. The book is presented as an act of transmission dedicated to the author's younger brother, whom she describes as the first ‘romano de’ Roma’ (a vernacular expression meaning ‘Roman from Rome’) in the family (Ben Mohamed Reference Ben Mohamed2018, 191, 230). Characters, places, practices, emotions and records of the transnational history of the Ben Mohameds are translated into the multimodal devices of a comic book. La rivoluzione dei gelsomini is hence an example of how comics may enable the emergence of trajectories marginalised by eurocentric and nationalist narratives of history with their traditional, culturally determined media. Thanks to the democratic process that began in 2011 with the Tunisian revolution, Ben Mohamed has had the opportunity to return to Tunisia and research the history of her family and of the country through materials made available for the first time, such as archival records, magazines and newspapers, but also interviews with members of her extended family and their social and political networks. The ambition to translate these private and official records into the complex narrative of a graphic memoir that would reclaim her personal family history as much as that of Tunisia has pushed forward Ben Mohamed's formal and aesthetic research. Even if her priority remains to document and gain visibility for subjects marginalised by the regime's history rather than to develop formal aspects of the comics medium, this graphic memoir reflects some of the tensions that pervade the representative strategies deployed in comics exploring the tension between testimony and fiction (Spiegelman Reference Spiegelman2011).

The first pages of the book set out the historical backdrop, and are dense with symbols, places and icons of the political history of Tunisia from the country's independence in 1956 to the coup of Ben Ali in 1987, which deposed the long-term leader Habib Bourguiba to establish a dictatorship tolerated by the major international partners in the region to facilitate the implementation of neoliberal politics and contain the increasing pressure of dissent and migration across the Mediterranean. In these first pages the realistic portraits of political and religious leaders, trade unionists and activists evoke the language of the media, the battles over symbols, slogans and news headlines. As the narrative enters the more intimate territory of family memory, Ben Mohamed's distinctive manga style returns, to be modulated throughout the book via the different settings and characters of the unfolding story.

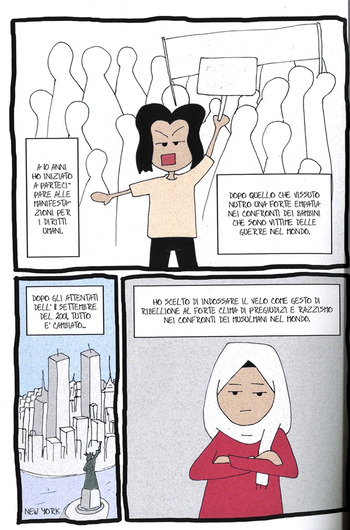

The remediation of family records is a classic example of the representative dilemmas confronted by comics authors, and of the multimodal translational strategies enabled by the medium. For example, in Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, the author Alison Bechdel (Reference Bechdel2006) painstakingly redraws family correspondence and photographs in a realistic style that engages even the handwriting used in the correspondence, delivering a sophisticated example of the translation of memory content into the comics medium. La rivoluzione dei gelsomini reproduces the Ben Mohamed family's letters in accordance with the manga style of her book. Rather than being redrawn or rewritten, the texts of the letters in Arabic are typed in the panels, whilst Italian translations are featured in side boxes, with the same lettering as the rest of the book (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Lettera dall'Italia (La rivoluzione dei gelsomini, courtesy of Takoua Ben Mohamed and Edizioni BeccoGiallo, Italy).

La rivoluzione dei gelsomini exemplifies the mnemonic practices of Ben Mohamed's family forced into a life of separation, secrecy and exile. The archive of correspondence, photographs and family records of this family were kept in barrels hidden under the dunes around their home in the desert, to be safe from searches by their political persecutors (Ben Mohamed Reference Ben Mohamed2018, 72–73). The book also illustrates the uneven trajectories of memories, people and objects across the Mediterranean, for example by mapping the route of those letters that travelled through family networks across Europe and North Africa before arriving at the family home (Ben Mohamed Reference Ben Mohamed2018, 76–77).

Exploring the political, affective and material dimensions of a transnational family, the book sheds light on the interconnected histories of Tunisia and Italy in times of postcolonial regimes. It challenges the longstanding – now indeed nostalgic – image of Tunisia as a placid multicultural country domesticated into a pleasant tourist destination for Europeans, revealing how such representations have been fostered on both sides of the Mediterranean, albeit with different agendas. Demonstrating the tremendous emotional echo of the 2011 revolution among Tunisian communities in Italy, La rivoluzione dei gelsomini highlights their marginalisation in Italian mainstream media and representations. In featuring such marginalised perspectives, the book opens new possibilities for mutual awareness and for the rewriting of the histories of both countries. Furthermore, by focusing on women, it reclaims a plurality of memories still disregarded by the post-revolutionary narratives of both countries – memories embodied in stories of activism and resistance of women of any religious sentiment. As Renata Pepicelli remarks, this plurality is illustrated by a panel that also echoes one of Marjane Satrapi's most widely known drawings: a female figure with a hijab covering only half of her head, which stands for all Tunisian women, regardless of their religious identification (Pepicelli Reference Pepicelli2018). At the same time, this book is a rare attempt to acknowledge the specific memory of resistance of female Islamists in its domestic and diasporic dimensions: for example, through the episode that sees Mounira responding to the threats and bureaucracy of the Tunisian embassy in Rome (Ben Mohamed Reference Ben Mohamed2018).

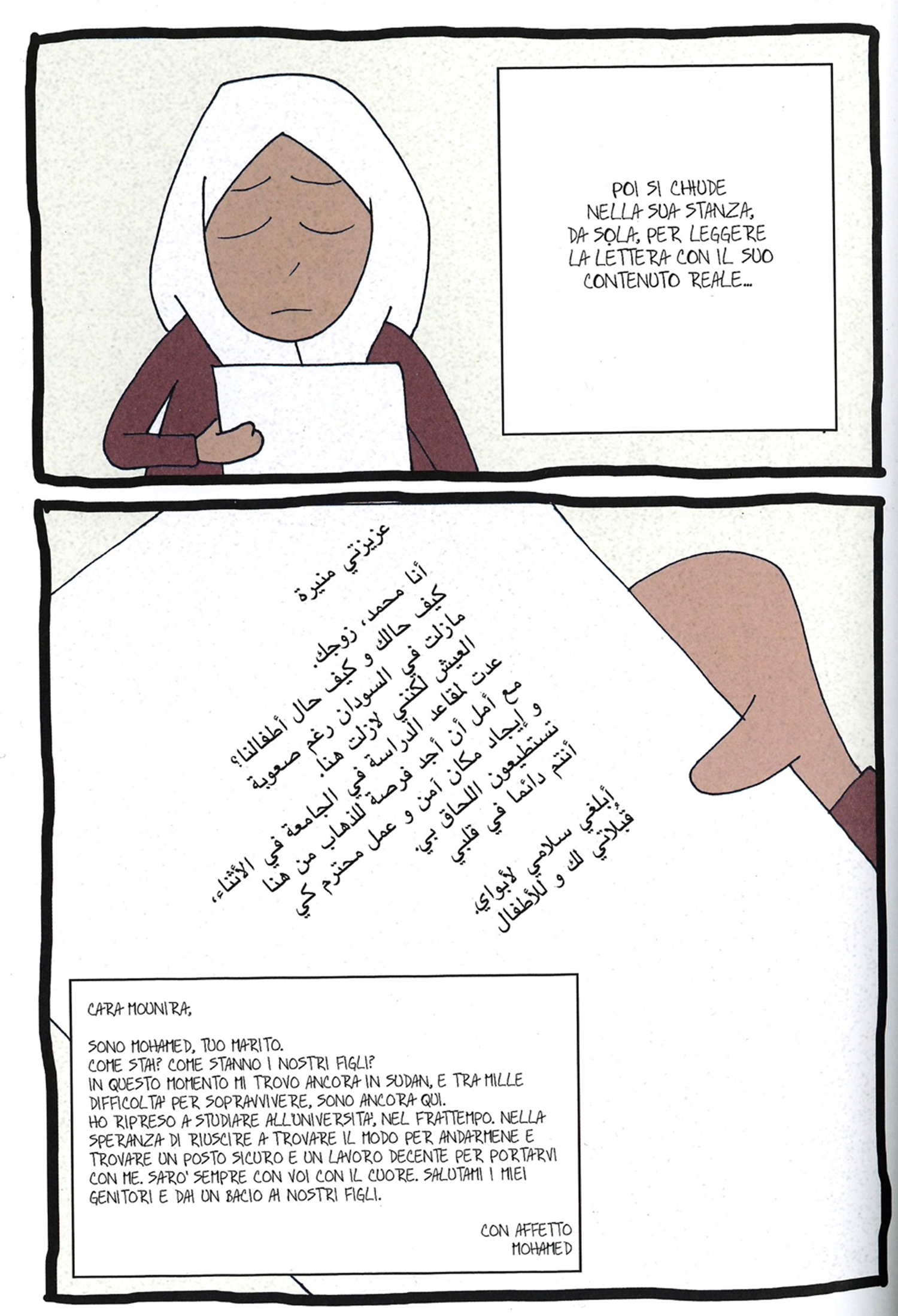

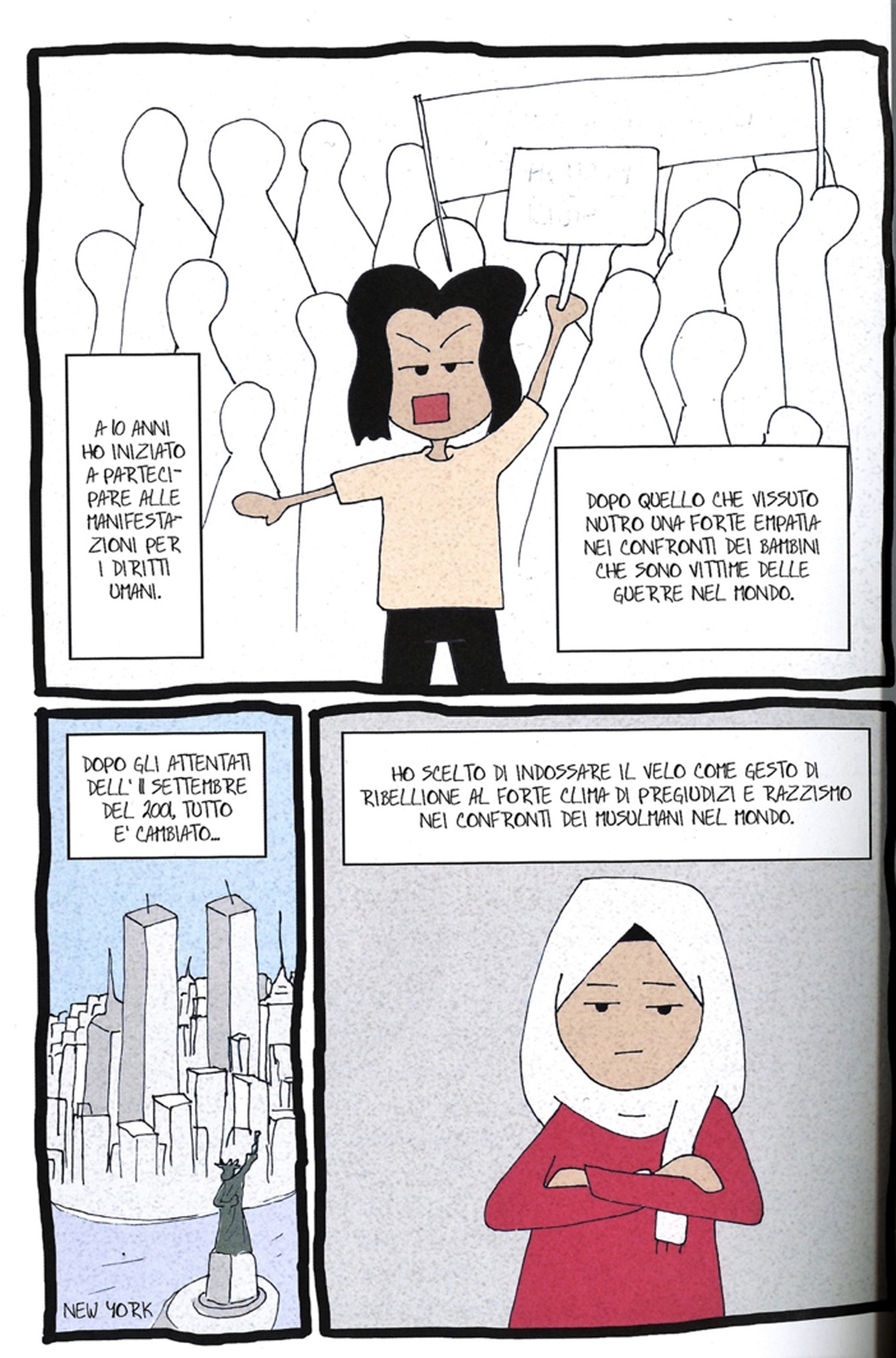

Through its use of the memories of a migrant child, the book also sheds light on children's strategies of self-expression beyond language barriers – such as making comics in the classroom – and participation in global political arenas. In the book, Ben Mohamed records her choice to wear the hijab as an act of rebellion on the part of a child sympathetic with the struggles of the oppressed around the world (Figure 6), against the racial prejudice and Islamophobia haunting Muslims since 11 September 2001 (Ben Mohamed Reference Ben Mohamed2018, 190).

Figure 6. La scelta del velo (La rivoluzione dei gelsomini, courtesy of Takoua Ben Mohamed and Edizioni BeccoGiallo, Italy)

Exploring family memory, La rivoluzione dei gelsomini visualises further dimensions of the transnational life of the author. While her early project represented Muslim lives in Europe and Rome, in this memoir Ben Mohamed draws Tunisia for the first time, engaging explicitly with aspects of the history of the country and its representation. The making of this book represented for her an opportunity to travel around that country, to research historical records and materials made accessible for the first time after the revolution, and to formulate her questions on home and belonging from a new location. The first panel enters the medina of Tunis in search of a path ‘home’ and an answer to a question recurrent in her work: ‘Chi sono io?’ (‘Who am I?’). The final page acknowledges the importance of this journey into individual and collective memory for continuing the transnational and transcultural journey of her life. The panel features the door of a Tunisian house opening between a garden and a street: an image of another liminal space that opens the possibility of being, and of navigating the multiple flows of individual and collective processes of identification across memories and cultures: ‘I don't know if this journey is one of leaving home or returning home. I don't know where home is. Whether in the deep south of Tunisia, in the Saharan desert, or in the busy streets of Rome. Some people tell me home is here, others that it is there. My past, my present and my future I keep always in my heart'. (Ben Mohamed Reference Ben Mohamed2018, 229).Footnote 5

Conclusion

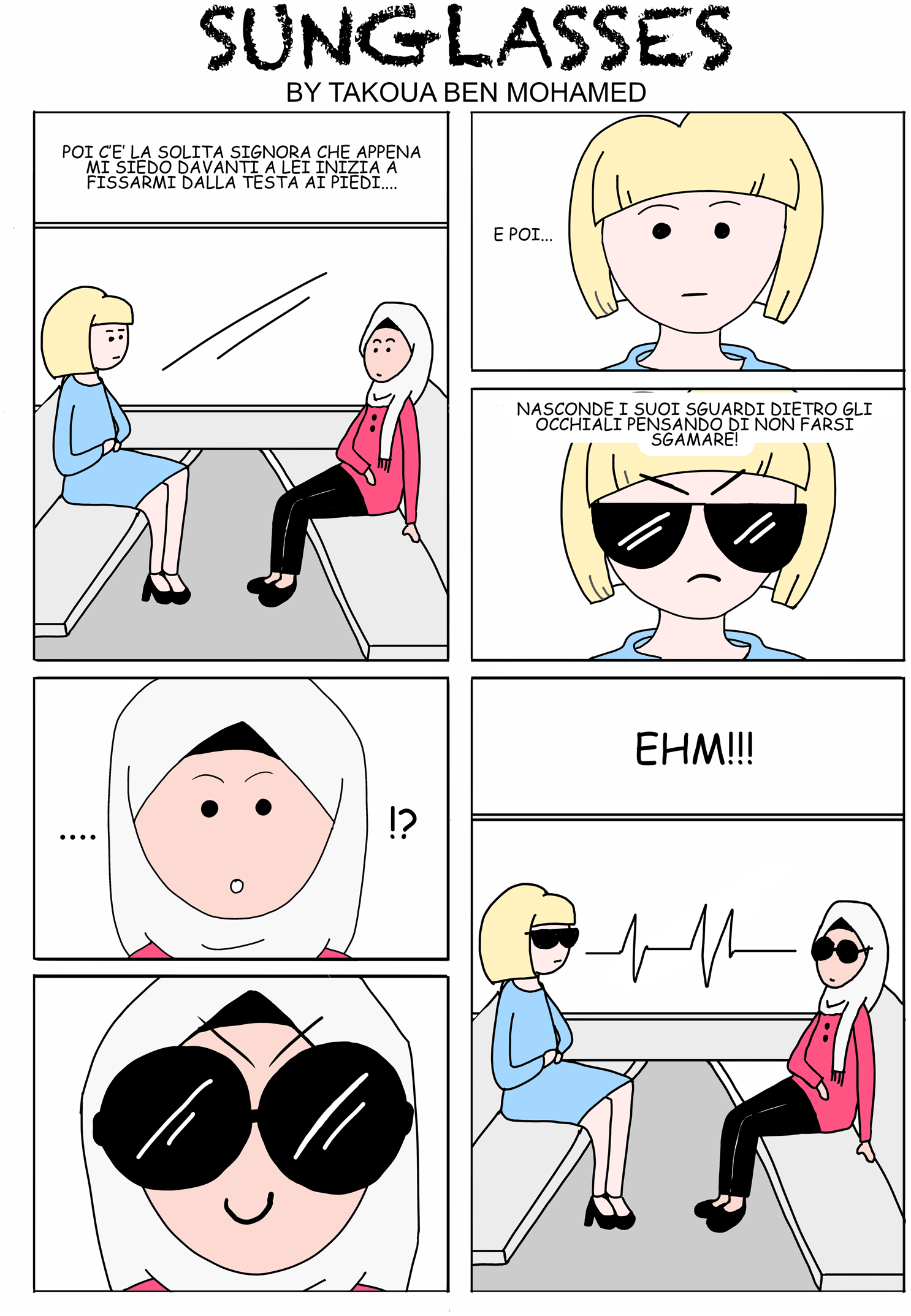

This article argues that by translating memories into comics, Ben Mohamed opens new spaces for transcultural exchange. ‘Sunglasses – occhiali da sole per la vittoria’ (‘Sunglasses – Sunglasses for Victory’) is a story that illustrates this point at multiple levels, since it was drawn for the blog of the hair salon Ricciocapriccio and set in Rome's underground rail network. The comic shows a white, blonde-haired woman that hides in silence behind sunglasses assuming to ‘not disclose herself ' (in Roman slang, di non farsi sgamare) while staring at a girl in hijab (Figure 7). Rather than succumb to the inquisitive attitude of the lady, the girl puts on large sunglasses of her own, returning the gaze, and then strikes back with a smile. This comic illustrates the bewilderment of transcultural experience and the common tendency to hide and judge from a comfort zone, avoiding engagement and any questioning of categories, practices and knowledge. At the same time, this comic is a creative response to this bewilderment.

Figure 7. ‘Sunglasses’. Courtesy of Takoua Ben Mohamed.

This article proposes an original framework to understand the power of comics as a transcultural medium in a mobile and multilingual world. As a flexible, accessible medium, comics enable multimodal forms of (self-)translation and memorialisation that expose the intertwined nature of memory and translation in contemporary processes of identification. Featuring comics as an emerging medium of memory in the twenty-first century, this article has proposed a linguistic-sensitive approach to the mobility of memory and culture – one that acknowledges the full complexity of linguistic and cultural mobility as well as the multiple dimensions of translation.

In addition, this article aims to raise awareness of the dynamism of the Italian transnational comics scene of the twenty-first century, and the ways in which it resonates with global trends in comics. The mobile geographies and emerging protagonists of this scene show that Italian culture is produced inside and outside Italy, in many languages and by people of increasingly different backgrounds, questioning mainstream and underground canons. Takoua Ben Mohamed's trajectory as a comics author and media professional illuminates some of the new directions of the Italian fumetto across and beyond genres and media. This complicates established representations of underground vs mainstream comics scenes, while also showing the increasing relevance of comics as a tool of communication in a world of multiple languages and memories. Ben Mohamed's graphic journalism conveys the experience of navigating the languages and cultures of twenty-first-century Italy, whilst her graphic memoir calls for new ways of representing its multiple, transnational histories. By engaging with Takoua Ben Mohamed's comics, this article furthers our understanding of the transnational and translational mobility of Italian memory and culture.

Acknowledgements

Transnationalizing Modern Languages: Mobility, Identity and Translation in Modern Italian Culture (TML) is one of the large grants under the ‘Translating Cultures’ theme of the Arts and Humanities Research Council, UK. The author of this article has been a member of the TML Project since 2014 and she thanks Loredana Polezzi, Charles Burdett, Renata Pepicelli, Takoua Ben Mohamed, Charles Forsdick and the editors of this special issue for their generous engagement with her research. Images courtesy of Takoua Ben Mohamed and Guido Ostanel and Federico Zaghi for Edizioni BeccoGiallo, Italy. Translations by Barbara Spadaro and Julian Watts: grazie mille.

Note on contributor

Barbara Spadaro is Lecturer in Italian History and Culture at the University of Liverpool, UK. The principal areas of her research are the history of Italians from North Africa, colonial and postcolonial migration, transcultural memory and the media of history in culture, notably comics. As a member of the TML research project she contributed to the exhibition Beyond Borders: Transnational Italy, featuring the comics of Takoua Ben Mohamed, in Rome, London, New York, Melbourne, Addis Ababa and at the Italian Cultural Institute of Tunis (2016–2018).