Introduction

The livelihood of men in any country is constantly, ineluctably connected to the existing environmental conditions, which means that it depends on the complex of physical and biological factors that determine and model the environment. Thus, when it comes to a discussion of whether an overseas country can accommodate a large wave of white migration, which means whether that country offers the right combination of factors allowing white colonisers to settle, live and work … and, finally, finding psychological and physiological conditions in line with those of the motherland, it is necessary to analyse every single constitutive factor of the environment (Zavattari Reference Zavattari1936, 51).

Professor Edoardo Zavattari, an expert in colonial biology, conceived the freshly achieved Italian imperial enterprise as an encounter of humans and nature, both metropolitan and indigenous, but also as an adjustment of those same humans and nature.Footnote 1 Indeed, he continued from the above quotation by stressing the paramount role of nature in determining the success and exceptionalism of Fascist Italian schemes in Africa, simultaneously accusing the previous regime of an instrumental approach to African nature through the metaphor of Aesop's fable The Fox and the Grapes. According to his interpretation, previous Liberal governments had depicted the colonies as unproductive and torrid arenas, simply to cover up their lack of will, faith and capacity.

This assumption can be reversed in order to reveal the new connection that Fascism established between its agenda and environment-building processes and, to go along with the fable's metaphor, to explore how Fascism shortened the distance between the fox and the grapes. The search for the perfect combination of social and ecological factors has been instrumental in serving and supporting several national and colonial policies (Pergher Reference Pergher2018; Armiero and Graf von Hardenberg Reference Armiero and von Hardenberg2013), as it was in envisioning and actually transforming Fascist overseas territories (Caprotti Reference Caprotti2014; Polezzi Reference Polezzi2014).

Up until the rise of Fascism, ‘emigrate’ was the watchword and our ministries had considered Italian emigration a ‘gift of civilisation and progress to other peoples!’ And the few, the elect group of staunch nationalists that had suggested ‘colonisation,’ were mocked and suffocated by malicious slanders and by the meaningless and inept, though mainstream, voice of public opinion. But now, due to the Fascist Revolution, which is establishing a new order, the terms are reversed and our own workforce must benefit the motherland, both in Italy and in the Colony, rather than making other peoples wealthy (Giglio Reference Giglio1929, 321).

This is an extract from the text awarded the first prize in the 1929 national high school essay contest, written by Carlo Giglio, the soon-to-be eminent scholar of European colonialism (Calchi Novati 2002). The text addresses another Fascist leitmotiv, the combination of strengthening colonial aspirations with the long history of emigration as a means to confer new arguments of political legitimation on both colonial and emigration policies (Deplano Reference Deplano2018a, 73–6; Ipsen Reference Ipsen2009, 90–144; Labanca Reference Labanca, Bevilacqua, De Clementi and Franzina2002a; Labanca Reference Labanca2002b, 72, 106–7). Expansion replaced emigration; first pioneers, then colonisers replaced emigrants.

These shifts were orchestrated by a main actor, the state, so it is of some interest to look at institutional innovations introduced from the 1920s. These frame the progression from emigration flows to colonial transfers and the extension of the area of intervention from the nation sensu stricto to the nation inclusive of colonial possessions. These reforms also show the tendency to align internal migration and colonisation with a third element, the idea of land reclamation.

The 1924 Serpieri Act was an official step in this direction; in 1926 a permanent Committee for Internal Migration was established as an advisory group within the Ministry of Public Works; in 1928, a Commissariat for Migration and Internal Colonisation was created as a direct agency of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers. In parallel, between 1926 and 1928, the idea of a demographic colonisation of Libya emerged and, finally, in 1932, the Agency for the Colonisation of Cyrenaica (later on renamed as the Agency for the Colonisation of Libya, hereafter ECL) launched its plans for agricultural and demographic colonisation in collaboration with the Ministry of Colonies and Commissariat for Migration and Internal Colonisation (Cresti Reference Cresti2009, 381; Protasi and Sonnino Reference Protasi and Sonnino2003, 105–6; Gaspari Reference Gaspari, Bevilacqua, De Clementi and Franzina2001; Cannistraro and Rosoli Reference Cannistraro and Rosoli1979, 684). Mussolini tried to channel human and more-than-human flows towards an intensive exploitation of African soil and to turn Italy into an imperial power.

The transformations of the Libyan environment under Fascist rule (1922–43) reveal themselves as crucial to an exploration of the interaction of the four key terms this paper considers: Fascist colonisation; Italian migration and identity formation outside the national borders; environment-making processes; and social and ecological transfers.

Socio-nature on the move in the context of colonialism: a new approach

This paper takes an environmental history approach to examine a critical shift in Italian efforts at colonisation in North Africa. The shift under scrutiny is precisely the passage described widely in primary sources as the end of ‘the heroic phase of the individual adventure’, in which Libya served as a private possession and zone of conquest for a bunch of individuals, and the beginning of the phase in which ‘the demographic-type Libyan colony represents the direct continuation of the motherland, … a collective good’ (Sangiorgi Reference Sangiorgi1938, 7). The exploration of this shift from an environmental perspective aims to provide a novel expression and interpretation of the trajectory of the agricultural enterprise in Libya from the inception of Fascist rule in 1922 to its collapse in 1943. The proposed framework relies on an analysis of the ‘environing’ strategies enabled by and connected to social and ecological flows. The achievement of the creation of Libyas suitable for different categories of Italian Fascists is presented here as an environment-building undertaking in which the ‘environing’ (Sörlin and Wormbs Reference Sörlin and Wormbs2018, 103–105) is combined with regime-building actions and policies. Placing the processes through which humankind impacts nature and shapes the environment at the service of authoritarian means and within authoritarian infrastructures highlights the effective collaboration between nature and politics and the configuration of ecologically unequal exchanges (Givens, Huang and Jorgenson Reference Givens, Huang and Jorgenson2019). Fascist Libyan environments appear as historical products within specific material and non-material frames, expressing the bond between colonisation, migration and the Fascist government (Sörlin and Warde Reference Sörlin, Warde, Sörlin and Warde2009, 3–4).

In this article, I adopt three fundamental analytical tools. In all state enterprises, and specifically in Fascist colonial ones, claims over spaces and lands represented key elements in the exercise of control over communities and natures (Graf von Hardenberg et al. Reference Graf von Hardenberg, Kelly, Leal, Wakild, von Hardenberg, Kelly, Leal and Wakild2017, 1–4). As its first analytical tool, this article operationalises the environment, based on the assumption that any historic environment shows the inextricable nexus of social and ecological elements: according to Fascist rhetoric, there is no distinction or separation between ‘national landscape’ and the ‘people's spirit’ and ‘racial quality’ (Armiero and Graf von Handenberg Reference Armiero and von Hardenberg2013, 292–4). Furthermore, the communities and natures this paper addresses are not only those located in the colonial space; the forging of Fascist colonial landscapes also affected and incorporated metropolitan animals, plants, humans, soils and imaginaries. Indeed, the expansion of state authority into novel and peripheral areas requires the envisioning and materialisation of national landscapes mirroring specific societal values and fostering the creation of national identities (Armiero and Graf von Hardenberg Reference Armiero and von Hardenberg2014).

The second analytical tool employed here to explore the environmental dimension of Italian colonialism in Libya is the concept of ‘exchange’, or ‘transfer’ in its most recent variable (Capresi Reference Capresi and Demissie2016; Beinart and Middleton Reference Beinart and Middleton2004). Since the publication in 1972 of Alfred W. Crosby's (Reference Crosby2003) The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492, the movement of biological organisms – plants, animals, humans and diseases – has been seen as a decisive factor in ensuring the achievement of colonial schemes, and came to represent the foundational approach to the study of the environmental history of colonialism (Crosby Reference Crosby and Worster1989). As environmental historians and historical geographers have noticed, a full and proper understanding of colonial regimes requires ‘not only an appreciation of the social and economic forces at play – something historians have skilfully offered for a long time – but also an appreciation of ecological contexts and concurrent environmental trends’ (McNeill Reference McNeill2010, 3). The encounters of plants, animals, humans and soils express the social context of the eras in which they occur and represent relevant actors in region-forming processes: through which circuits do human and ecological actors move and settle? What kinds of things and meanings travel in a bundle with these actors? (Kull and Rangan Reference Kull and Rangan2008, 1258–9). Flows have proved themselves extremely appropriate for the investigation of issues connected to Italianness, namely the ‘condensed essence’ of the fact of being Italian outside national borders (Demaria and Sassatelli Reference Demaria and Sassatelli2015, 311), and issues relating to colonial and imperial environments (Kirchberger and Bennett Reference Kirchberger and Bennett2020). The Italian project of demographic colonisation was ultimately a ‘disciplined, controlled and s heltered transfer’ (Sangiorgi Reference Sangiorgi1938, 8). In this paper, as a third tool, I attempt to further expand the analytical potential of flows by using them to explore the intersection of Italian migratory phenomena and the making of Fascist colonial environments. To merge those two lines of enquiry, this paper adopts and adjusts questions and approaches outlined by Marco Armiero and Richard Tucker (Reference Armiero, Tucker, Armiero and Tucker2017, 7–10) in their edited volume, Environmental History of Modern Migrations. In the following sections, migrants appear not only as ‘pioneers taming the frontiers’ but also as settlers with ‘stories of exploitation, of competition with other ethnic groups over access and control of natural resources, of failure in adapting to new socioecologies’ (Armiero and Tucker Reference Armiero, Tucker, Armiero and Tucker2017, 8). Although a migration framework can hardly integrate colonial mobility patterns, primary sources and existing scholarship label the intensive Fascist demographic project in North Africa as a case study of either Italian migration (Labanca Reference Labanca, Bevilacqua, De Clementi and Franzina2002a) or Italian mobility (Ben-Ghiat and Hom Reference Ben-Ghiat and Hom2016; Ben-Ghiat Reference Ben-Ghiat2015, 78–117). Such sources and studies make this paper appropriate for publication here (Figure 1).

Figure 1. ‘The Mediterranean: the centre of the Roman civilization’. Illustration by C. Celano in L’Azione Coloniale, 15 March 1934. Courtesy of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism (MiBAC). National Central Library of Florence. No reproduction permitted.

Together with this aspect, the limited space for and scope of a paper entail inescapable pitfalls. A thorough appreciation of the environment of Italian rule in Libya should include a more in-depth engagement with herding and farming practices, scientific experiments and technical problems and advances; should establish continuities between the first Fascist decade and the Liberal period or, at least, with the very last colonial initiatives taken by the Liberal governments. The astonishing gap between the weight that natural environments and resources hold in primary sources and the almost non-existent scholarship in the environmental history of Italian colonialism is a strength, but it is also the root of this paper's weakness, since some conceptualisations cannot fit into existing scholarly discussions.

Aware of these limits, this paper aspires to bring the reader into the rhetorical and concrete environments of an Italianised Fascist Libya. As the opening vignette indicates, the paper's argument draws on an analysis of Italian colonial texts, especially articles from L'Italia Coloniale, to unpack the shifting rhetoric and cultural perspectives related to Italy's colonial experiences in Africa. L'Italia Coloniale serves as the principal guide in this journey for two reasons: it was an illustrated and extremely popular magazine of the time and, consequently, can convey the regime's voice at its best; and, in contrast to other sets of sources, it covers the whole time period considered in this paper and performs perfectly the goal of a 20-year-long reconstruction. Finally, similar trends, topics and terms borrowed from this source can be found in other coeval printed texts and archival files that are accounted for here only briefly.

The reconstruction I present shows that the environing of Italian Libya was not informed by the same principles, actors and purposes over the two decades of Fascist rule. The paper explores the development of the rationale behind strategies grounding and fostering environmental changes and the installation of white settlers along the so-called Fourth Shore of Italy between 1922 and 1943. As demonstrated by scholarship on Italian colonialism, 1932 marked a watershed in the colonial trajectory in Libya (Labanca Reference Labanca2012; Cresti Reference Cresti, Ben-Ghiat and Fuller2005, 79–80; Massaretti Reference Massaretti2002). A few tendencies, which until that date competed with other narratives and schemes, became dominant and were progressively reinforced by contextual factors during the following years.

The next sections proceed as follows: they explain how the Libyan environment was differently constructed in its material and immaterial domains during the first and second decades of the Fascist era; they trace human and non-human transfers in these constructions; they link this analysis with the geopolitical, economic and social issues that contributed and gave grounds for the development of the state enterprise of demographic and agricultural colonisation. The concluding remarks reflect on how the construction, appropriation and exploitation of Libyan steppes and oases add yet another layer to the historical account of the Italo-Libyan enterprise, and aim to question long-lasting myths of Italian colonialism and recast the idea of its exceptionalism.

A Libya for Italians and Italians for Libya: the Fascist ‘miracle’

In 1931, Arnaldo Mussolini went to Libya to witness the colonisation process, report on it and encourage Italian rural migrant workers ‘to attempt Libya’.Footnote 2 In Tripoli, he opened a meeting with local fascists with the following words: ‘I have nothing more to discover in Libya. Everything worthy to be seen has already been discovered’ (Gori Reference Gori1939, 99). Once back home, Arnaldo Mussolini – journalist and editor-in-chief of the newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia, and Benito Mussolini's brother and collaborator – published a series of five articles and, based on his own experience, described Libya in contradictory and inconsequential terms. The soil was basically sand, but not as arid as normal sand; temperatures were not African and Libyan heat was dry and bearable; the ghibli wind blew, but not so often; no one had seen water, though there were rich supplies of groundwater; the region had a sense of emptiness, but it was inhabited by indigenous communities willing to serve agricultural development (Gori Reference Gori1939, 99).

Apparently, Arnaldo Mussolini was endorsing a change of pace and in fact he firmly removed the aura of mystery around colonial territories, thus marking the end of Libya as an unknown space. In 1931, the regime's propaganda succeeded in representing Libya as a colonial domain, understandable to Italians after a ten-year-long approach that had swung between the argument of the ‘mysterious countries’, instrumental to the stimulation of curiosity (Borghetti Reference Borghetti1924, 88), and an overflow of information about a myriad of institutional visits, scientific and geographical expeditions, pioneers’ and travellers’ experiences, enabling Italians to see the colonies through someone else's eyes (Deplano Reference Deplano2018b; Behre Reference Behre2017). This evolution of the image of Libya, one of Africa's lesser-known regions, undermined an enduring criticism of Italian expansionism (Argon 1937, 7–8; Vinassa de Regny Reference Vinassa de Regny1913, 10; Bignami Reference Bignami1912, 3–5). In 1928, one of the strongest means to nurture Fascist colonial dreams, but also one of the strongest counterarguments to colonial investment, was precisely the lack of adequate information about the physical geography of large areas of Libya. The disproportion between the scale of the potential agricultural development and the real extent of the colony appeared striking: agrarian expert Andrea Gravino deemed 25,000 sq. km suitable for cultivation out of the 900,000 sq. km of Tripolitania, and 25,000 sq. km in Cyrenaica out of a total area of 600,000 sq. km, leaving out the southern desert wastes (L'Italia Coloniale 1928a, 32). In the spring of 1931, to sort out the discrepancy and fill the knowledge gap, immediately after the Italian army claimed to have taken over indigenous populations, the Royal Italian Geographical Society proceeded with the scientific exploration of the least known regions of the vast North African dominion. Between 1932 and 1936 the Society despatched eight expeditions into the Libyan Sahara (Atkinson Reference Atkinson2003, 16–18; Atkinson Reference Atkinson1996).Footnote 3

Arnaldo Mussolini was not equally firm in presenting Libya as an ideal destination for masses of Italians. He was cautious, and the inconsistencies in his interventions mark a clear shift away from conceptualisation of the Libyan environment towards the envisioning of the perfect Fascist colony. I argue that his series of articles represents the litmus test of the new direction of Italian colonisation. His texts addressed all the recurring elements through which the propaganda machine shaped a national, colonial mindset present in the political agenda of the time: soil and land, climate and water, metropolitan and indigenous peoples.

1922–31: A colonisation for the few

It took ten years for Libya to become a country where it was possible to develop intensive agricultural projects and to move thousands of Italians, specifically farmers (Miserocchi Reference Miserocchi1932, 23). In 1922, agricultural economist Rodolfo Forlani quoted Ghino Valenti's warning about the dangers and difficulties of farming the Libyan steppes: North Africa would never replace the Americas as a destination for migrants and, at least for the time being, would not enrich Italy, quite the opposite (Forlani 1922, 18). Given the high-risk enterprise, Italian convicts and indigenous prisoners could be organised, as indeed they actually were, into agricultural penal colonies under the supervision of and in collaboration with soldiers already based in Libya (Vacca Maggiolini Reference Vacca Maggiolini1928, 168–9; Forlani 1922, 121–3). Over this first phase, the lure of easy profits, domination and heroism motivated a few individuals to obtain large agricultural concessions; a closer look at these pioneers shows us that this early wave of migration included aristocrats or the upper middle class, great landowners and great estate administrators, most of whom had neither a rural background nor sympathy for the peasants (Piccioli Reference Piccioli1928a, 139–40; Piccioli Reference Piccioli1928b, 178–80). The availability of a challenging open-air laboratory and the chance to carry out scientific experiments, attracted agrarian experts – Giuseppe Leone, Luigi De Santo, Armando Maugini, and Helios Scaetta, amongst others – to Tripolitania. Young soldiers were also assigned farms in the surroundings of prisoner-of-war camps, where ‘militia villages’ were established (L'Avvenire di Tripoli 1933).

These three groups embodied the three pillars of the Fascist reclamation scheme in Libya – war, faith and science – and expressed an elitist conception of colonisation. Environment itself mirrored the idea of colonisation as a superior attribute associated with an elite. When these men reached the African shore in the early 1920s, all of them faced a solitary savannah battered by winds; a scarce, rationed water supply that was not drinkable; extreme weather conditions; sandy or rocky soil; and a complete absence of infrastructure (L'Italia Coloniale 1925, 23; L'Italia Coloniale 1924, 58). Despite these conditions, all of them achieved the ‘miracle’ (Scaetta Reference Scaetta1925, 8) of the ‘development of the sand’ (Leone Reference Leone1928, 14), and all of them fought against the ‘silent conspiracy of natural elements’ and won through against nature, ‘the old enemy’ (Piccioli Reference Piccioli1928b, 179–80). During the first years of Fascist rule, colonies were not for everyone – colonies were for extraordinary, skilful, firm men, ready to sacrifice themselves and give up on all the comforts of the motherland (Leone Reference Leone1930, 7). The early-stage transformation of Libya resembled a ‘creation ex-nihilo’ (Teruzzi Reference Teruzzi1938, 115; L'Italia Coloniale 1938a, 136; Piccioli Reference Piccioli1928c, 204), an all-encompassing reclamation, ‘civil’ (Piccioli Reference Piccioli1928c, 206), ‘social’ (Piccioli Reference Piccioli1928a, 139) and agricultural. Mussolini's men crafted Italian Libya from scratch: they built an infrastructure; shaped docile and disposable indigenous people in the colony to the imperial culture of Italy; transferred a huge amount of plants from Italy, with the clear aim of materially correcting local ecological conditions and making them more suitable for Italian agricultural production and its level of productivity. Figures and expectations introduced in all the above-mentioned texts appoint the olive tree as the main protagonist of this pioneering period, along with grapevines, carob, and almond trees. The olive's resistance to thin soil and prolonged droughts made this plant the symbol of agricultural conquest (Acerbo Reference Acerbo1937; De Cillis Reference De Cillis1924) and pointed to the future of the colony as ‘the land of trees’, instead of insisting on proclaiming North Africa as ‘the granary of Rome’Footnote 4 (Borghetti Reference Borghetti1928, 116). Twenty million olive trees were expected to be planted in Libya and develop its soil in the years to come (L'Italia Coloniale 1928b, 116); meanwhile, by the end of 1930, Italian farmers had planted more than 953,000 olive trees over a surface area of 317 sq. km (Cavazza Reference Cavazza and di Bologna1933, 138).

1932–43: A colonisation for the masses

An elitist colonisation and the resulting construction of an inhospitable environment were linked with data on the distribution of Italians abroad. In 1927 Italian emigrants resident abroad amounted to a total of 9,168,367. The American continent got the lion's share, with 7,674,583 Italians (83.71 per cent), followed by European countries with 1,267,841 units (13.83 per cent); 27,567 people (0.3 per cent) moved to Oceania and 9,674 (0.1 per cent) to Asia. Africa was the chosen destination of 188,702 Italians (2.06 per cent), most of whom did not move to the Italian territories in North and East Africa. Instead, the Italian population in Africa converged on Tunisia, Egypt, Algeria, and Morocco (L'Italia Coloniale 1928b, 191). To reverse or correct these trends and persuade people to move to Italian territories, the state progressively entered the scene as the main regulatory body of agricultural schemes and increased control over migration flows. Difficulties and risks did not disappear and the passive trade balance of the colonial agricultural sector could not be overlooked, though these issues were considered temporary and under the jurisdiction of ministries and state authorities (Ornato Reference Ornato1938a, 63; Leva Reference Leva1938, 97; Vendettuoli Reference Vendettuoli1936, 35). Even under autarchic policies, Libya was never called upon to act as a market for metropolitan products or a supplier of raw materials, unlike Italian East Africa. Libya was primarily assigned with the medium-term goal of self-sufficiency by reaching an adequate production of oil, fat, meat, wheat, fruit, and fodder (Di Lauro Reference Di Lauro1939, 2).

Farmers should have been lured to Libya by the outstanding results of public and private investments, an awareness of the comfortable safety net and other social sector programmes and, especially, by conditions on the ground. During the 1930s, persistent propaganda turned the image of Libya inside out; simultaneously the environment played a prominent role in matching rural migrant workers’ interests with governmental goals.

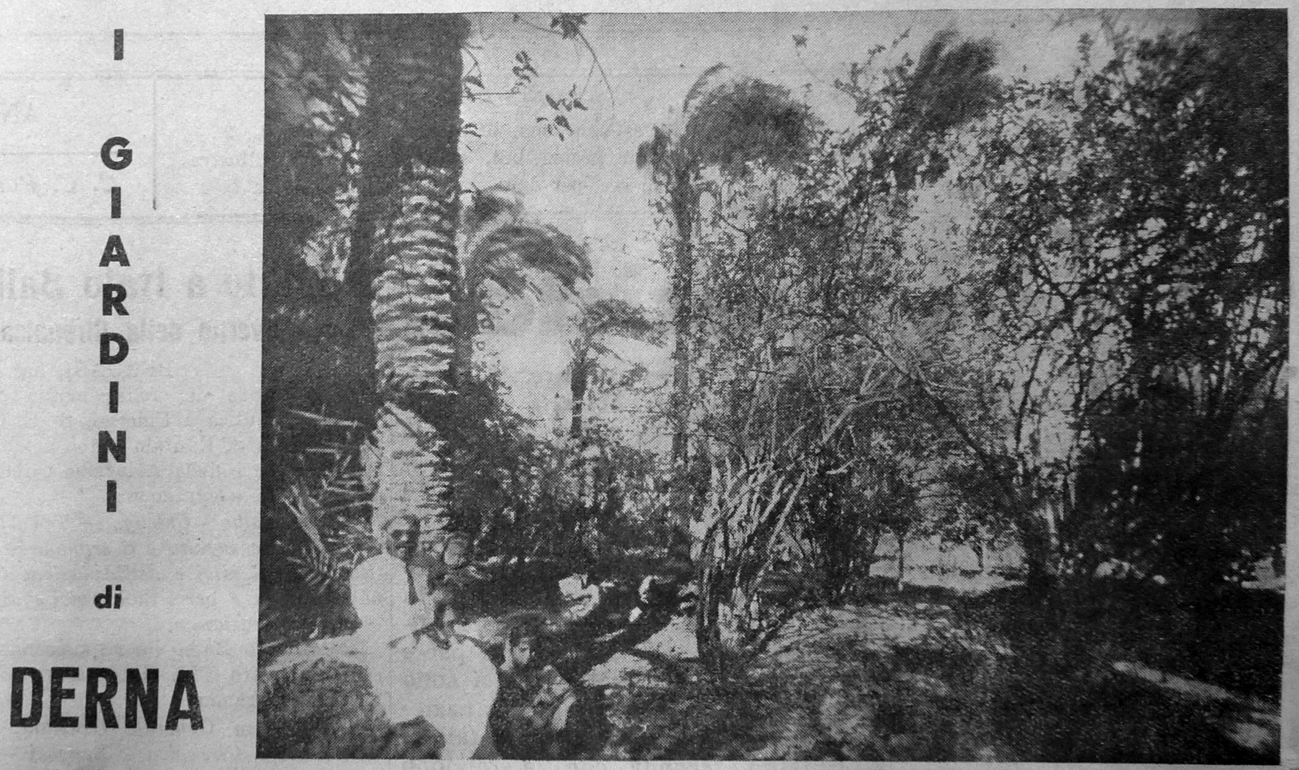

The coastal area around Tripoli appeared as an ‘agrarian paradise’, blessed by ‘eternal spring’, where villages, surrounded by tall trees acting as a windbreak, protecting them from the desert, were full of animals and trees loaded with colourful and ripe fruit. Kilometres of robust crop plantations alternated with fields of flowers and experimental plots (Figure 2).

Figure 2. ‘Derna’s gardens’ in L’Azione Coloniale, 3 August 1933. Courtesy of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism (MiBAC). National Central Library of Florence. No reproduction permitted.

Water flowed into fountains and ponds; a network of irrigation channels was supplied by an artesian well (L'Italia Coloniale 1936c, 86). Two of the main enemies, extreme heat and drought, seemed tamed. Agricultural reclamation established a village of 18 families in El Azizia, approximately 40 kilometres south-west of Tripoli, an area notable for its extremely high temperatures and prolonged droughts (El Fadli et al. Reference El Fadli2013; Court Reference Court1949), and it was an exemplary demonstration in favour of the Fascist rural colonisation scheme (L'Italia Coloniale 1936d, 151). More relevant was Libyan governor Italo Balbo's proclamation that ‘the eternal problem of water’ had been definitively sorted out by the mid-1930s, following the launch of a programme of extensive drilling that had no equivalent in either Europe or Africa. Technicians sank boreholes reaching as deep as 400 metres, achieving the ‘miracle’ of a water supply (Ornato Reference Ornato1938b, 123–4). A successful resolution to sandy desert winds was about to come, thanks to the growth of tree and root barriers (Cristaldi Reference Cristaldi1938, 111–12). In 1932 the development of Cyrenaica started and followed the same pattern. Former sandy and stony military camps on the plain surrounding Al-Marj, and in earlier times Barce, were fertilised for agriculture, based on scientific and rational criteria. From 1933, the land yielded increased crop products, wheat in particular, and the progressive transformation of the soil allowed for the cultivation of fruit and olive trees, cotton, castor-oil plants, flax and vegetables (De Bernardinis Reference De Bernardinis1939, 12–13).

By early 1938, the Cyrenaic Gebel, the area that was about to receive one third of the Italian families relocated to Libya, had undergone the civil and agricultural reclamations already described: existing villages were expanded and others were ready to be begun, hundreds of new houses and public buildings were built, and infrastructure and roads were constructed. The Arab wild green mountain remained only in the memories of the living and was transformed into ‘the Green Umbria’, a reference to the hilly region in central Italy. The Gebel was literally ‘changing its face’ (R. 1938, 122). Fascist officials curated every detail to offer rural migrants a physical Fourth Shore of Italy and ban any feelings of nostalgia (Perricone Violà Reference Perricone Violà1938, 153).

The last step was social reclamation. In 1938 the general government of Libya submitted to Mussolini a plan for the ‘intensive demographic colonisation’ of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. The plan aimed to impose Italian interests and control over indigenous peoples and land for indefinite lengths of time, and to modernise farming activities through the financial and logistic intervention of the state. Thirty-one thousand Italians – men, women and children, defined as an ‘army of workers’ – were transferred to Tripoli and Bengazi in 1938 and 1939 and, from there, allocated to newly built villages (Cresti Reference Cresti, Cresti and Melfa2006, 40–3; Nobile Reference Nobile1990, 173–88).

The Italianisation of the colonial space in this second phase also included non-human transfers. The progressive development of rural villages in selected areas of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica was planned in three stages: first, the eradication of weeds and shrubs for ploughing, seeding and planting to secure adequate conditions for the newcomers; second, the import of Italian livestock and the introduction of adequate agricultural machinery and equipment; finally, the settlements of selected immigrants and the start of intensive or extensive cultivation (ECL n.d.). Each land unit – between four and 20 hectares according to ecological variabilities – included a precise amount of both indigenous and Italian animals and plants. The ECL and the National Fascist Institute of Social Security (Istituto Nazionale Fascista della Previdenza Sociale, INFPS), the two main institutions running the agricultural and demographic colonisation under state supervision, arranged for the transport of thousands of Italian working animals and livestock and millions of olive trees, fruit trees and other trees to act as windbreaks, besides the import of food, fodder, and fertilisers to Libya (INFPS 1936–42; ECL 1939a).

The conceptualisation of a demographic colonisation via agriculture highlights how ecological control pairs with social control, particularly in authoritarian and colonial contexts. Libya acted as a ‘living laboratory’ to use Helen Tilley's (Reference Tilley2011) expression, for various kinds of expert, and as a ‘social laboratory’, attributable to the social policies connected to the countryside. Echoing what Omnia El Shakry (Reference El Shakry2007, 17–18) wrote about colonial Egypt, Fascist Libyan landscapes described ‘the peasantry as cultural artefacts of national identity’ and, in the particular Italian migration to Libya, the population constituted ‘an object of knowledge and social intervention and engineering’. In the next section, I enter Italo-Libyan colonial society by looking at the chain of oppression and exploitation that came along with the human and non-human transfers.

Environments of oppression

Fascist Libyan socio-nature resulted in a negotiated space between competing groups and ideas of nature that unfolded in unexpected ways. The Fascist regime adopted several strategies to incorporate indigenous peoples and their farming practices, to displace and lighten national tensions, to implement policies and test social and political theories. The enactment of both a colonisation for the few and a colonisation for the masses intertwined with complex dynamics of inclusion/exclusion and liberation/oppression involving both Italians and Libyans.

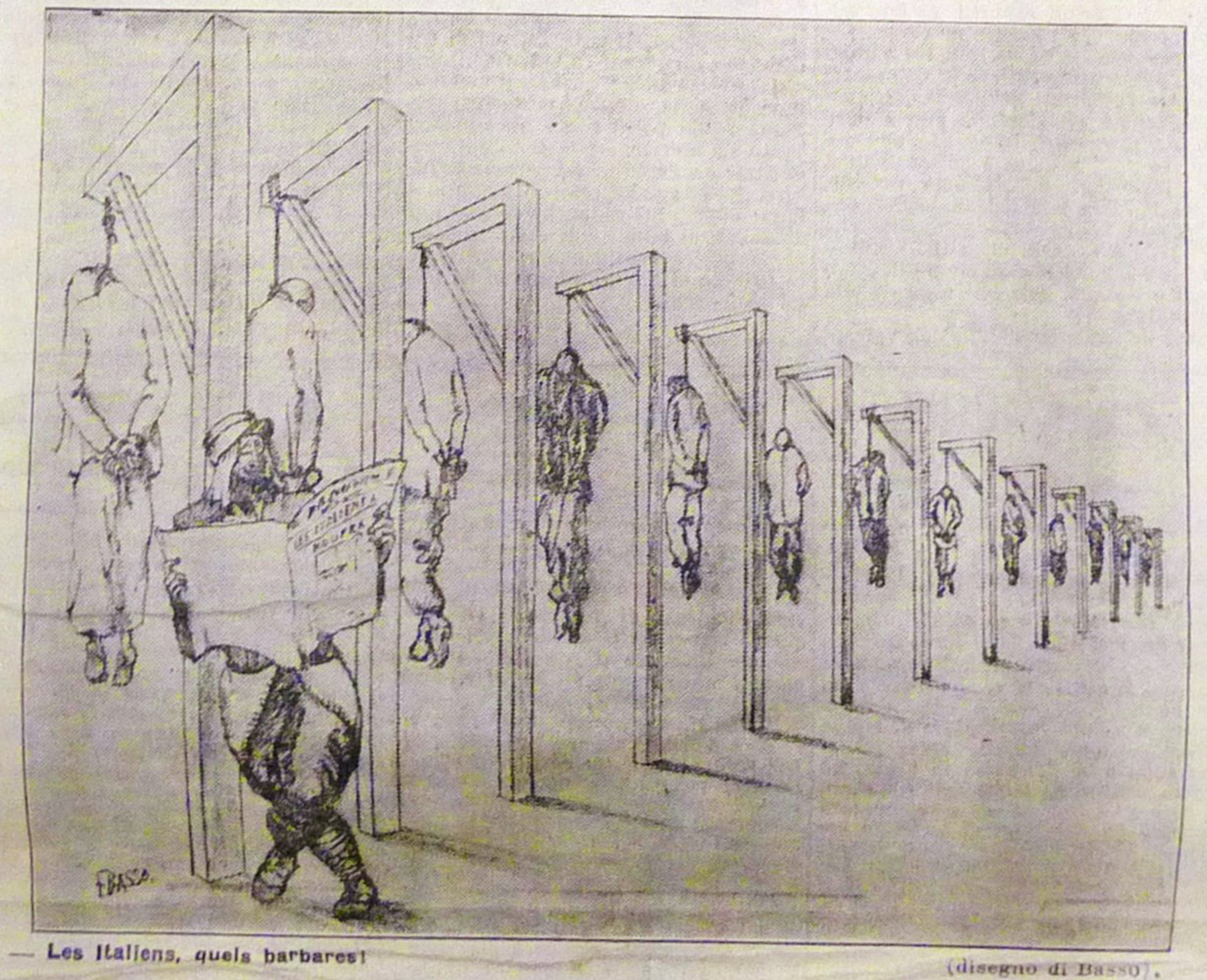

The colonial Libya where the first pioneers and established soldiers could perform their creatio ex-nihilo constituted the outcome of the 1922–32 environing. Two previous moves made room for such an environment. The arrival in the autumn of 1923 of somewhere between 1,500 and 3,000 young Italian men, acting under the auspices of the Voluntary Militia for National Security, wreaked havoc in the coastal cities of Libya. Their transfer fulfilled two tasks: it exported a potential threat to the conservative brand of Fascism, the institutionalisation of the Fascist movement and the formation of the party; and at the same time armed squads offered an inexpensive backup for colonial troops, just a few months after the colonial ministry initiated the ‘reconquest’ of the Libyan interior (Ryan Reference Ryan2015, 123–8). This heralded the beginning of a fluctuating troop transfer during the Fascist period (Speziale Reference Speziale2018, 103). The Italian colonial army reconquered Tripolitania in 1924 and Cyrenaica in 1932 and these two dates marked the inception of an Italian colonial domain and the consequent beginning of the agricultural development of the two regions. Italian land acquisition meant the expulsion of the rebels from the northern areas of Tripolitania (Cavazza Reference Cavazza and di Bologna1933, 106–7) and the internment of the population of Cyrenaica (Figure 3).

Figure 3. ‘Les Italiens, quels barbares!’. Satirical illustration by F. Basso on the international outcry after Italian troops took over Cufra and repressed the Libyan resistance. In L’Azione Coloniale, 21 June 1931. Courtesy of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism (MiBAC). National Central Library of Florence. No reproduction permitted.

By 1924 the region of Fezzan had become a refuge for most of the resisting Tripolitanian tribes, who kept control of the region until 1930, when Italy's modern aircraft and poison gas finally overcame them. The tribes fled to Chad, Niger, Egypt and Tunisia (Ahmida Reference Ahmida2009, 106–7). Between 1930 and 1933, 16 concentration camps operated in the Syrtica region, where 85,000 tribe members and their families were imprisoned and exposed to physical and cultural violence. For most of them, this remained a one-way journey (Ahmida Reference Ahmida2020; Hom Reference Hom2019, 100–8; Ahmida Reference Ahmida2009, 107; Ahmida Reference Ahmida2006, 182–90; Labanca Reference Labanca, Ben-Ghiat and Fuller2005). In 1933, the 35,000 survivors were allowed to return to their original villages and were forced to collaborate with Italians (Ardemagni 1933, 234–7). In fact, despite the fight against nomadism, the expansion of the European agricultural frontier did not reduce the space of nomadic agricultural practices (Micale Reference Micale1979, 65); instead, metropolitan and indigenous communities competed for the same areas and water resources (Medici Reference Medici and Ghazaleh2011; Fantoli Reference Fantoli1935, 194). In this capacity, Libyans appeared as farm labourers on great estates and plantations and as a workforce in the building of infrastructure and villages for white settlers (Bassi Reference Bassi2018; Pomilio Reference Pomilio1935, 11–16). Dislocation and dispossession prepared for the launch of the 1932–43 environing.

To keep control over native resistance and the newly acquired land required an Italian presence and the favourable conjunction between national and colonial policies, which fostered the Italian people's colonisation plan (L'Italia Coloniale 1936b, 49). The 1927 census of migrants served the new directions of both the demographic and migration policies the regime was about to enact. In May, Mussolini's Discorso dell'Ascensione marked the beginning of ‘a fascist obsession’ with quantitative demographic concerns as a sign of social vitality and political power (Ipsen Reference Ipsen2002, 95–6; Livi Reference Livi1937); in November, the first measure halting rural-urban mobility paved the way for other regulations, striving to replace international migration with internal and colonial flows (Gallo Reference Gallo2018, 144, 166–7). The state did indeed intervene on the colonial front and in 1928 Governor Emilio Del Bono decreed that the process of agricultural expansion, although remaining under private initiative, sought to place Italian peasant families, regulate the distribution of land and avoid the creation of large estates. The outcome of state support was fairly immediate: in 1929, 455 families settled in Tripolitania, a total of 1,778 people, and four years later the number of families rose to 1,500, bringing the total to 7,000 people (Capresi Reference Capresi2009, 36–9). Between 1932 and 1934, the profit-driven and agricultural colonisation was first recast into a para-state, socially-orientedFootnote 5 and rural project and, then, especially from 1938, into a state enterprise serving defence policies, military strategy and autarchic plans (Biasillo and da Silva Reference Biasillo and da Silva2019, 159–68; Cresti Reference Cresti2011, 179–214; Istituto Agricolo Coloniale di Firenze 1947a, 34–8; ECL 1941a; Afrus 1938, 182). Approximately 39,000 Italian colonists occupied about 3,700 sq km in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica by the end of 1940, unevenly distributed between state land grants, private properties and colonisation companies (Fowler Reference Fowler1973, 492–3; Istituto Agricolo Coloniale di Firenze 1947a, 113–17; Istituto Agricolo Coloniale di Firenze 1947b, 18–20).Footnote 6

Italian farmers were called upon to embody and showcase Fascist identity and contribute to the Italianisation of the environment. They were the regime's longa manus in a peripheral area, its pliant tools carrying out the above listed government duties while transforming themselves into owners of their plots, getting rid of their subaltern position in their hometowns and undergoing their social redemption along with the land (Stresino Reference Stresino1939, 70–1; ECL 1942). To reduce the possibility of failures in such operations of human reclamation and adaptation, the state introduced selection criteria, male and female acclimatisation camps (L'Italia Coloniale 1938b, 151), systems of sanitary, technical and social control (ECL 1941b; ECL 1935; ECL 1932), not to mention education programmes for both indigenous and metropolitan children. But the reality did not live up to expectations. Selection criteria were often skipped and ‘undesirable elements’ were sent to the colony (ECL 1941c). Farmers did not free themselves from uneven power relations, ecological constraints and state supply dependency; life in rural villages in the middle of desert wastes was at best uncomfortable and during the war unbearable, when entire villages were displaced in more secured areas (ECL 1946, 4; INFPS 1936; ECL 1941–42). The same went for imported or local animals: they were not moved from one spot to another to avoid lethal drought (L'Italia Coloniale 1936a, 38); the regime did not always prevent deaths by starvation due to the lack of fodder; and from the late 1930s they were killed or stolen by impoverished Libyans. Most of the plants brought over by the Fascists never reached maturity, nor did they bloom or yield a product; during the war many of them died in storage rooms waiting to be shipped, while several specimens were not even allowed to leave Libya because they were riddled with pests (ECL 1941d, 6–14).

The intensification of Italian flows ‘did necessarily lead to the absolute exclusion of Arabs from an extremely vast territory, the best of Libya in terms of pastures, distribution of rainfall, fertility of the soil’ (ECL 1939b) and determined yet another internal flow. Governor Balbo, in an attempt to halt indigenous incursion into Italian villages, granted Muslim populations permission to graze animals in three so-called ‘Muslim villages’, where 131 semi-nomadic and nomadic families could conduct their farming activities. Balbo failed in improving living conditions for native communities, or in encouraging them to contribute to the development of the colony and preventing resistance to the Italian occupation (Cresti Reference Cresti2011, 215–26). Despite being within a framework of oppression, the incorporation of local groups indicates that they played an active role not only in reducing the scope and limiting the achievements of Italian colonisation, but also in redirecting Fascist projects and making those projects include the needs of non-whites.

One last flow is worthy of mention. In 1938, when the Italian parliament passed the Racial Laws, the Jewish population of Libya numbered roughly 30,000, with 22,500 living in Tripolitania. From 1940, the regime initiated a deportation campaign and Jewish people with Libyan citizenship were interned in newly built concentration camps around Tripoli. Jadu (former Giado), a mountain town about 180 km away from Tripoli, was the site of the largest Italian concentration camp during the Second World War, containing 2,584 prisoners. ‘Survivors at Jadu described the day as being filled with illness, cruelty and exhaustion’ (Hom Reference Hom2019, 109–10).

For many humans and non-humans, Italian Libya signified, simply, oppression.

Conclusion

This paper offers an overview of the formation of Fascist Libya using the environment as a historical place of encounter for social and ecological phenomena and as a historiographical knot tying together migration and colonialism. As shown, the environment did not remain an isolated or passive category, but it proved itself instrumental in determining societal aspirations and behaviour and engaged with a vast array of policies developed in other domains. In administrative and propagandistic primary sources, the ideological and economic significance of the natural environment – which in the case of Libya took the shape of agricultural landscapes – calls for better appraisal and an acknowledgement of ecological elements as objects and subjects of historical transformations.

In this paper, I have shown how the emergence of a colonial mentality in Italy, the creation of rural villages in Libya, and the implementation of policies directly or indirectly related to migration and colonisation, passed through the environment, and the two-decade-long environing produced and intertwined with two processes of meaning-making. The first semantic change concerned the term colonisation, which became synonymous with demographic colonisation and the unrealistic best-case scenario of one million human transfers to the Libyan provinces in the following years (Barbaro 1939, 33–4; Stresino Reference Stresino1936, 131). The second semantic change concerned the term migrant: this no longer indicated the poor Italian begging for a piece of land in a foreign country, but came to mean the Fascist peasant, who sustained his numerous family through his hard work and the fertility of his farm (Montefoschi Reference Montefoschi1939, 80). In 1938–9, when both colonisation and migration processes converged, the joint phenomenon of ‘demographic expansion’ emerged and marked the complete Italianisation and fascistisation of Libya, encompassing ecological and social levels. Coastal Libya was ready to be annexed by the Italian kingdom and at this point in time the to-be-colonised African Libya ‘belonged to a remote past, culturally more than chronologically distant’ (Bonfiglio Reference Bonfiglio1938, 50).

This convergence stood for the elected narrative late Fascism produced of its own colonial enterprise. In such a progressive narrative, the government support in the early 1920s for large concessions and the industrialisation of agriculture (Ongaro Reference Ongaro1938, 17) – what I called the colonisation for the few – has been reinterpreted as a preparatory phase for the blooming of an exceptional Fascist colonial project (Narducci Reference Narducci1942, 89–107; Giglio Reference Giglio1939, 7–13). Besides the content, the disproportionate amount of sources produced before and after 1932 is misleading and such asymmetry demands historical evaluation. The environment expresses the different paths taken by the colonisation, keeps track of the attempts and discontinuities of its trajectory and shows the different ideas on how to better colonise Libya throughout the competing agricultural schemes and social relations. Agricultural practices, subaltern voices, the conundrum of nation-colonies, different kinds of sources, should all be taken into account to further unfold the environmental dimension of Fascist rule in North Africa. Only recently has environmental history started to open the Pandora's box of Italian colonialism and new research is needed.

This comprehensive appraisal of the time period 1922–43 enriches the debate on the periodisation of the construction of a Fascist Libya and invites historians to look into it with means other than the traditional lens of settler colonialism (Verracini Reference Verracini2018; Ertola Reference Ertola2017). The first phase of Fascist colonisation of Libya and its legacy need to be thoroughly explored to continue questioning Fascist exceptionalism (Labanca Reference Labanca, Thomas and Thompson2018) and to unsettle the myth of a demographic enterprise based on the improvement of a barren, empty territory (Ballinger Reference Ballinger2016, 815). A comparison within the realm of environmental historiography between the Italian case and other colonial enterprises facing similar ecological challenges and geopolitical conditions will foster the general debate on colonialism, particularly on late colonialisms (Fedman Reference Fedman2020; Isenberg, Morrissey and Warren Reference Isenberg, Morrissey and Warren2019; Saraiva Reference Saraiva2016, 137–234; Davis Reference Davis2007).

Notes on contributor

Roberta Biasillo is a Max Weber Fellow at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies of the European University Institute in Fiesole (Italy) and she is conducting research on the environmental history of Italian colonialism in Libya under Fascist rule. Roberta has studied in Italy where she obtained a PhD in European History from the University of Bari in 2016. Her PhD dissertation looks at Italian nation- and state-building processes in the nineteenth century through the lens of forests.

She has worked at the Environmental Humanities Laboratory of the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, at the Italian National Institute of Social Security and at the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society of the LMU in Munich. Besides the nexuses nation-nature and colonialism-agriculture, she is also interested in historical theory and environmental humanities research methodologies.