Introduction: La Tradotta del Fronte Giulio

The Italian army of occupation in Yugoslavia during the Second World War has been described as ‘a very poor military formation’. Its badly led, poorly trained, ill-equipped, and unmotivated conscript soldiers struggled against an aggressive and ably directed partisan resistance movement that exploited the local terrain (Osti Guerrazzi Reference Osti Guerrazzi2011, 63–70, 126). Within this context, the maintenance and improvement of troop morale became on overriding concern for Italian military commands in the theatre. To combat the tedious life of occupation duty and to bolster the fighting spirit of the troops, military propagandists supplemented films, news dailies, and periodicals brought in from Italy with field newspapers edited and printed on site by propaganda sections at the corps and army level. The most significant of these field newspapers, in terms of size, content, and distribution, was La Tradotta del Fronte Giulio.

Beginning in June 1942 as a four-page broadsheet, La Tradotta del Fronte Giulio was the official weekly of the Italian Second Army, whose forces occupied parts of Slovenia, Dalmatia, Croatia, and Bosnia between 1941 and 1943. Inspired by a famous trench newspaper of the First World War, La Tradotta eschewed traditional news bulletins in favour of more literary and satirical articles and illustrations, either professionally commissioned or submitted by amateur military personnel. The newspaper’s emphasis on entertainment and culture made it reasonably popular among soldiers. By 1943, it had doubled in size to eight pages, and Second Army’s Propaganda Office was printing 25,000 copies each week (Della Volpe Reference Della Volpe1998, 285–288).

Like the soldier newspapers of the Great War, La Tradotta provides a unique window into ‘the negotiated beliefs often shared by officers and their troops’ (Nelson Reference Nelson2011, 18). Although propaganda was more centralised under Fascism and not always guided by ‘realism’ (Isnenghi Reference Isnenghi1980, 45), military propagandists still recognised the need to produce material that responded to the state of mind of the troops and which soldiers would accept as authentic (Audoin-Rouzeau Reference Audoin-Rouzeau1992, 33–34; Nelson Reference Nelson2010, 168).Footnote 1 Despite the richness of La Tradotta as a source it has been little used by historians, with the important exception of an article published in 1972 by Teodoro Sala. This is probably because – like most other Italian soldier newspapers of the war – copies of La Tradotta are only accessible in fragmentary collections held in various private and public archives (Della Volpe Reference Della Volpe1998, 287).Footnote 2

The newspaper’s publication run from mid-1942 through the Fascist collapse of July 1943 spanned a period of transition for Italy’s war effort, marked by defeats in North Africa and the Soviet Union, when faith in an eventual Axis victory faltered (Minniti Reference Minniti1996, 100–104; Manca Reference Manca2006, 126). For the Second Army in Yugoslavia, this period saw the withdrawal and consolidation of garrisons to compensate for its exhausted and depleted manpower following a series of destructive but inconclusive anti-partisan operations (Burgwyn Reference Burgwyn2005, 195–196). As a result, the imperialist and irredentist propaganda that accompanied the Italian annexation of Dalmatia and Ljubljana in 1941 – and which remained present in the pages of La Tradotta (Sala Reference Sala1972, 99) – needed to be reinforced with other themes.

In their efforts to fashion some meaning and sense of purpose behind occupation and counterinsurgency in Yugoslavia, military propagandists situated Italian soldiers as standard-bearers and defenders of italianità. In the process, contributors to La Tradotta provided their own definition of Italian identity, bringing together an eclectic and often contradictory array of influences that had co-existed uneasily throughout the Fascist ventennio. Chief among these competing influences were Fascism’s racialised concept of the nation – expressed in juxtaposition with the Slavic communist Other encountered in Yugoslavia – and Catholic portrayals of piety, charity, and universality.

This paper does not aim to exhaustively catalogue the themes present in La Tradotta. Instead, it focuses on the departures and intersections between race and religion in the army’s representations of the model Italian soldier and his mission in occupied Yugoslavia. Historians have highlighted the intersecting roles played by modern ethno-nationalism and traditional religious discourse as tools for mass mobilisation during the First World War. All of the belligerent European nations produced ‘war cultures’ that fused religious and patriotic sentiments to make sense of the unparalleled slaughter of that conflict. Race and religion combined to present the war as an existential struggle between contrasting civilisations. These concepts helped to define both the national community and the demonised enemy Other; they also fuelled myths of sacrifice, martyrdom, and resurrection that gave spiritual meaning to the conflict (Audoin-Rouzeau and Becker Reference Audoin-Rouzeau and Becker2002; Kramer Reference Kramer2007; Becker Reference Becker2010). The case of La Tradotta reinforces James McMillan’s (Reference McMillan2011, 69) observation that, although the Second World War is typically understood as a struggle between secular ideologies, religion continued to play an important role in cultural mobilisation well after 1918. Fascist war culture blended together the regime’s ideology and racism, the traditional nationalism of Italy’s military establishment, and Christian impulses that reflected the mental universe of much of the Royal Army’s rank and file.

After contextualising Italian military propaganda within the ideological and political framework provided by Fascist race-thinking, Catholic responses to Fascism, and the Italian army’s relationship to Fascism and Catholicism, this paper will analyse the ways in which La Tradotta inserted religious language into the racialised discourse of the Fascist regime. The pages of La Tradotta employed Catholic symbols and themes in three interconnected ways: first, as a means of demonising the communist and Slavic enemy that Italian occupation forces confronted in the Balkans; second, as a more generic justification and explanation for soldiers’ suffering, through Catholic language of piety and sacrifice; and, third, to present Italian soldiers as humane members of a ‘Christian fraternity’ that rendered care and aid to the destitute, regardless of racial difference.

Fascism, Catholicism, and military culture

The sometimes complementary, sometimes conflicting relationship between Catholicism and Fascist ethno-nationalism in Italian military propaganda can only be understood within the pre-war and wartime context of Italian Fascist racial discourse, church-state relations, and military culture. Fascist identity was racially informed, defined against Jewish, African, and Slav Others. The Fascist regime’s efforts to incorporate Catholicism into its political religion meant that the use of Catholic themes in propaganda was not unprecedented. Throughout the ventennio, Catholic and Fascist thought often overlapped, including on race. However, with the onset of war, Fascist and military leaders in Italy worried that Catholic qualities of universalism and meekness conflicted with their models of the ideal soldier. The Fascist and military leaderships both sought to exploit select elements of the Catholic belief system on their own terms, to reinforce national unity and civic-military values of discipline and obedience.

Fascist racism

An ‘anthropological revolution’, through the regeneration of the Italian race and the creation of a Fascist ‘new man’, was the guiding mission behind Mussolini’s Fascist regime (Gentile Reference Gentile2009, 166–167). Modelled after the legionaries of Imperial Rome and steeped in concepts of soldierly masculinity, the ideal new man was heroic, athletic, dynamic, disciplined, virile, militaristic, and willing to sacrifice himself for the nation (Patriarca Reference Patriarca2010, 141–149; Willson Reference Willson2013, 240; Ponzio Reference Ponzio2015, 5–6). Race and racial consciousness became key attributes of the new man in the 1930s. With the invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, the implementation of segregationist policies in the colonies after 1936, and the introduction of antisemitic propaganda and legislation in 1938, Fascism embarked upon its ‘imperial and racist phase’ (De Grand Reference De Grand2004; Ben-Ghiat Reference Ben-Ghiat2006). Mussolini considered racism, like war, to be a regenerative tool capable of uniting the national community against the excluded and demonised Other (Gillette Reference Gillette2002, 4).

Fascist racism in the immediate prewar years focused on anti-Africanism and anti-semitism. However, anti-Slavic racism had been a significant component of Fascism since the origins of the movement in 1919 (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2008, 36). Italian anti-Slavism had roots as far back as the Risorgimento, when Croat soldiers in Austrian service became equated with Habsburg oppression (Osti Guerrazzi Reference Osti Guerrazzi2017, 594). Combined with pro-Slavic Habsburg policies, new forms of nationalist-imperialist irredentism introduced concepts of racial struggle between Italians and Slavs, serving to radicalise anti-Slavism in the north-eastern borderlands at the turn of the century (Apih Reference Apih1966, 9–14; Collotti Reference Collotti1999, 34–35; Sluga Reference Sluga2000, 166). Irredentists discriminated against Croats and Slovenes based on ‘stock’ (stirpe) and the ‘natural superiority of Italian civilisation’ (Catalan Reference Catalan2015, 68). After 1915, this radical but provincial racial hatred was nationalised by wartime propaganda and then ‘codified’ by Fascism in the aftermath of the First World War (Cattaruzza Reference Cattaruzza2017, 55–68; Catalan Reference Catalan2015, 57–59; Collotti Reference Collotti1999, 52). The ‘Border Fascism’ that developed in the newly acquired region of Venezia Giulia became central to the creation of Fascist concepts of italianità or nationhood in the 1920s. By attacking Slovenes, Croats, and socialists, Fascism established Slavism as its opposing inferior Other, closely linked to the equally ‘un-Italian’ ideology of Bolshevism (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2008, 32–33; Sluga Reference Sluga2000, 165–166).

With the 1938 ‘Manifesto of Italian Racism’, the Fascist regime adopted biological racism as its official creed. However, Fascist theorists and propagandists continued to espouse other types of racism (Raspanti Reference Raspanti1994). Anti-Slavism remained more spiritual-cultural than biological in form and definition.Footnote 3 Fascists and nationalists depicted ‘Slavs’ – almost always lumping together various Slavic-speaking peoples – as an inferior race without history or culture, but they did not consider Slav minorities within Italy to threaten Italian bloodlines (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2008, 40–52). Rather, by invoking romanità, Fascist ideology and policy aimed to denationalise and assimilate the Slavic Other, reflecting ‘predominant views of the assimilatory power of Italian civiltà as definitive of Italian national identity’ (Sluga Reference Sluga2000, 168–169, 178). This did not render Fascist policy towards Slavs benign. Efforts to Italianise the borderlands by targeting Slavic schools, intellectuals, and clergy, forcibly changing Slavic family and place names, and dispossessing Slav peasants of land amounted to ‘cultural genocide’ (Collotti Reference Collotti1999, 56–57). Similar policies of Italianisation were extended to the annexed territories of Slovenia and Dalmatia after 1941 (Rodogno Reference Rodogno2006, 258–276). The legacy of nationalist-imperialist and Fascist cultural anti-Slavism would be most relevant to the Italian military occupation in Yugoslavia. Military propaganda had to relate to soldiers’ encounters with Croat, Slovene, Serb, and Bosnian populations, and with the Yugoslav communist partisan movement.

Fascism and Catholicism

The emergence of Catholic themes in the war culture of 1940–1943 reflected the entangled political and doctrinal relationship between Italian Fascism and Catholicism. Despite the ‘cosmological incompatibility’ of Fascism’s secular concept of national rebirth with Christianity as a ‘revealed theology of redemption’ (Griffin Reference Griffin2015, 49–50), Church and state in Fascist Italy established a mutually beneficial modus vivendi. Whether this collaboration was the result of ‘intimate and substantial’ complicity (Ceci Reference Ceci2017, 93) or tactical ‘accommodation’ (Ventresca Reference Ventresca2016, 151) is up for debate. What is clear is that the Catholic Church and Fascist regime shared overlapping outlooks on family policy, social welfare, ruralisation, austerity, and corporatism, as well as common enemies in liberal-democracy, capitalism, and socialism (Pollard Reference Pollard2008, 97–99). Mussolini viewed the Church as an instrument for governing while the papacy saw Fascism as the most suitable secular tool for the ‘re-christianisation of society’ (Nelis, Morelli, and Praet Reference Nelis, Morelli and Praet2015, 9). The result was the reconciliation of Church and state through the 1929 Lateran Pacts.

As a political religion directed towards the creation of the new man, Italian Fascism ‘tried to absorb the church into its own mythical universe.’ Catholicism became an integral component of the Fascist concepts of the ‘Italian race’ and romanità (Gentile Reference Gentile1996, 74). There would be nothing intrinsically novel or subversive in the army’s adoption of Catholic rhetoric and themes in its propaganda in Yugoslavia. However, Fascists had always been selective in their use of Catholicism, choosing as models not meek and humble saints but crusading ‘political and warrior spirits who wielded both sword and cross’ (Gentile Reference Gentile1996, 63). By 1943, military propaganda was employing both models to inspire Italian troops.

Catholic responses to Fascism’s conceptualisation of a violent, racially conscious new man dedicated to the state were ambivalent. By rallying to the flag during the First World War, Italian Catholics had demonstrated that their religion no longer was ‘in radical conflict with the nation’. The Church accepted traditional nationalism and patriotism as morally legitimate forces but denounced ‘extreme nationalism’ that amounted to ‘statolatry’ (Ceci Reference Ceci2017, 48–51; Ponzio Reference Ponzio2015, 43–44). Upholding traditional ‘just war’ doctrine, Italian Catholic thinkers rejected pacifism and internationalism without sharing Fascism’s concept of war as a positive ideal (Moro Reference Moro2005).

Similar ambiguity and tension were apparent in Catholic responses to Fascist racism. Even if ‘the theological essence of Catholicism remained universalistic’ (Pollard Reference Pollard2007, 439), Catholic teaching did not deny the existence of races or the legitimacy of race-thinking. Rather than advocating universal charity, moral theology of the period established a ‘hierarchy of love’ that favoured members of one’s own nation or race above outsiders (Connelly Reference Connelly2012, 41). During the late 1930s, the pope denounced the ‘idolatric doctrine of the race’ and upheld the idea of ‘one single great universal Catholic human race’. However, these condemnations were qualified by his acceptance of racial hierarchies as ‘biological fact’ and, lacking the power of an encyclical, they were easily ignored by European Catholics who had absorbed modern understandings of race (Connelly Reference Connelly2012, 47–50).

Prior to the Second World War, the racially driven policies of the Fascist regime benefited from the functional complicity of the Catholic Church. In Venezia Giulia, Italian clerics shared the regime’s anti-Slavism and the Vatican ultimately accepted the forced Italianisation of the local clergy – thereby diminishing the anti-clerical tendencies within irredentist circles that had perceived Slavic priests as nationalising agents – in order to avoid a political breach with Fascism (Matta Reference Matta1981). The war in Ethiopia, which launched the regime’s imperial-racist phase, received enthusiastic patriotic support from the Italian Church, while the Vatican’s official neutrality functioned in Mussolini’s favour (Virtue Reference Virtue2013). The Church supported Fascist colonial legislation against racial mixing on the moral grounds that it prevented promiscuity (Ceci Reference Ceci2017, 190–195). In 1938, the Italian episcopate greeted anti-semitic propaganda and legislation with indifference, while some Catholics added their own anti-semitic discourse grounded in their equation of Jews with the perils of anti-clerical modernity (Ceci Reference Ceci2017, 232–34; Miccoli Reference Miccoli1997).

Despite this legacy of collaboration, Fascist authorities perceived a growing tension with Catholicism upon Italy’s entry into the Second World War. As a group, Italian clergy greeted Mussolini’s intervention in the war with ‘coldness’. They called for the faithful to perform their patriotic duties as citizens but maintained a reserved and ‘exclusively spiritual’ attitude towards the war that transformed into moral opposition by 1942–1943. Fascist police and prefects invariably judged Catholic attitudes negatively, as unenthusiastic, divisive, and pacifistic (Malgeri Reference Malgeri1980, 11–15). Responding to the lack of enthusiasm in Italy for war, Mussolini blamed the Catholic Church for having ‘unnerved and devirilized’ the Italian people (Patriarca Reference Patriarca2010, 136–137). He accused Catholics of preaching pacifism and of ‘making war without hating the enemy’ (Ceci Reference Ceci2017, 277). The complex and shifting relationship between Fascism and Catholicism meant that the incorporation of religious themes in Italian war propaganda, while rooted in a decade of intersecting discourse, was contested. The regime perceived a contrast between the Fascist and Catholic models of the ideal Italian soldier.

Military culture

La Tradotta del Fronte Giulio was a military publication that reflected the core values and ethos of the Royal Italian Army. The Italian officer corps espoused a gentlemanly, bourgeois, and paternalistic code of honour at odds with the Fascist vision of the new man, but in many other ways its worldview overlapped with that of Fascism (Rodogno Reference Rodogno2006, 150–152; Minniti Reference Minniti1996, 89–90). Alongside the army’s mythologisation of the Great War, its disenchantment with liberalism, and its vehement anti-socialism, race-thinking provided an area of affinity with Fascism. After the First World War, the military administration in Venezia Giulia adopted an irredentist programme and abetted local Fascist violence against socialists and Slavs, including clergymen seen as guardians of Slovene and Croat national identities (Mondini Reference Mondini2006; Bartolini Reference Bartolini2008, 31–34, 61–62, 102–104; Cattaruzza Reference Cattaruzza2017, 91–98). Thanks to the army’s key role in Liberal and Fascist campaigns in Africa, Italian military culture was further steeped in colonial attitudes that saw echoes in Yugoslavia (Sala Reference Sala1991). Despite the army’s pragmatically driven policy to protect Yugoslav Jews from Nazi and Ustaša persecution, anti-semitic views also were widespread among Italian senior officers (Rodogno Reference Rodogno2006, 405–406).

By granting Mussolini’s government its ‘clear and decisive’ support after 1922, the Royal Army maintained its structural autonomy through the Fascist era (Rochat Reference Rochat2005, 146–147). This independence extended to the field of military propaganda (Falsini Reference Falsini2013, 249–250). With mass mobilisation during the Second World War, the armed forces took an expanded role in producing and censoring propaganda material for its personnel in collaboration with Minculpop, the Fascist Ministry of Popular Culture (Cannistraro Reference Cannistraro1975, 220). Field newspapers like La Tradotta were edited and produced by propaganda officers attached to Italian military command staffs. Propaganda officers, mostly reservists with civilian experience in communications, functioned as intermediaries between army and regime. By 1942, Fascist party membership was required of all propaganda officers, but they remained subordinate to military commands rather than to Minculpop.Footnote 4 The content of La Tradotta reflected the conditional Fascistisation of the army’s propaganda apparatus. It echoed broadly Fascist themes – including imperialism, irredentism, romanità, racism, anti-communism, and proletarian nationalism – without offering much overt praise of Mussolini’s regime; the adjective ‘Fascist’ appeared only rarely in its pages.Footnote 5

The army’s relationship with Catholic religion was still more ambivalent. The Royal Army was a traditionally secular institution, going back to its key role after unification as ‘forge of the nation.’ The Italian officer functioned as ‘lay priest’ in a civic religion based on the ‘warrior-king,’ martyrs of the Risorgimento, and regimental icons, to the exclusion of the Catholic Church (Mondini Reference Mondini2004, 74–75). If by 1914 the army had moderated its anti-clericalism in response to the rise of socialism and Catholic acceptance of patriotic nationalism (Mondini Reference Mondini2004, 79–83), religion continued to play little role in the preparation of Italian officers until the signing of the Lateran Pacts (Balestra Reference Balestra2000, 121, 272). Despite the laudable service given by chaplains in the First World War, the army did not welcome Mussolini’s decision to establish a permanent chaplaincy, the Ordinariato Militare (OM), as part of his rapprochement with the Church. The army viewed the OM as a threat to its autonomy and insisted that chaplains be restricted to providing ‘spiritual assistance’ – that is, mass and confession – to the troops, without functioning as propagandists (Franzinelli Reference Franzinelli1991, 36–37; Falsini Reference Falsini2013, 150, 157).

Italy’s military leadership under Fascism remained suspicious of religious values. These suspicions were accentuated by the army’s inferiority complex, which it shared with Fascists, over the ‘view of Italian people as soft, cowardly and reluctant to fight’ (Riall Reference Riall2012, 152; Hof Reference Hof2016, 117). Like Mussolini, Italian senior officers equated Catholicism with pacifism. Even clerically minded generals, who argued that organised religion could promote militaristic values of obedience, selflessness, sacrifice, discipline, and duty, admitted that the concept of ‘Christian meekness’ (mansuetudine cristiana) was incompatible with soldiering (Bollati Reference Bollati1927, 20). During the First and Second World Wars, Italian officers blamed rural Catholicism and chaplains for the reluctance of Italian soldiers to hate their enemy (Isnenghi 1977, 163; Franzinelli Reference Franzinelli1991, 44).Footnote 6 In wartime, hatred of the enemy was one of the most important values that the military establishment wished to spread among the troops. According to directives from the Comando Supremo, it was the duty of all commanders and propaganda officers ‘to exalt aggressive spirit, love for combat and hatred against the enemy’ in order to secure fighting efficiency and unit cohesion.Footnote 7 Reflecting General Roatta’s intention to do away with the notion of the ‘bono italiano’ in Yugoslavia (Legnani Reference Legnani1998, 159), La Tradotta declared that ‘the good Italian soldier learns to hate!’Footnote 8

Enemies of faith and family

Although the army did not consider hatred to be a Christian value, military propagandists in Yugoslavia employed Catholic symbols and language to bolster their ideologically and racially motivated messages of hate and fear against the communist-led Yugoslav partisan movement. The most substantial intersections between Fascism, racism, militarism, and Catholicism represented in La Tradotta centred on the alterity of the Slavic communist partisan enemy. Although Fascist domestic propaganda avoided discussing the ongoing insurgency in the Balkans (Osti Guerrazzi Reference Osti Guerrazzi2011, 24), the nature of the guerrilla enemy was the focal point of military propaganda directed towards Italian troops in the theatre (Sala Reference Sala1972). Traditionally hostile to irregular forms of warfare (Whittam Reference Whittam1977, 77–80), the army depicted partisans as an illegitimate, frustrating, nefarious, and cowardly enemy, shirking from open combat in favour of ‘surprise’ and ‘traps’.Footnote 9 Italian military authorities offered no quarter to captured partisans, who were to be ‘immediately shot on the spot’ (Burgwyn Reference Burgwyn2004, 318). As an article in La Tradotta explained, ‘the survivors that surrender understand, more than our limited Slavic vocabulary, that much more eloquent [language] of our rifles.’Footnote 10

Italian army commanders and propagandists were particularly obsessed with the communist nature of the partisan enemy. Portraying counterinsurgency in Yugoslavia as a war against communism had several benefits: it was consistent with 20 years of Fascist anti-socialist propaganda, it defined the conflict as defensive rather than expansionistic, and it connected the undistinguished role of occupation duty to the frontline operations underway against the Soviet Union (Osti Guerrazzi Reference Osti Guerrazzi2011, 34). As Marla Stone (Reference Stone2012a, 85) has demonstrated, Italian anti-communist propaganda aimed at the Soviet enemy on the eastern front ‘seamlessly intertwine[d] commitment to Catholicism and the Fascist cause.’ The same can be said for military propaganda in Yugoslavia. The soldiers of the Second Army were told that they too were part of an anti-communist ‘holy war’ or ‘crusade’ in defence of ‘the nation, family, religion, and justice.’Footnote 11

The concept of a holy crusade against communism adopted Christian rhetoric and was consistent with Catholic teachings. Seeking to mobilise an international response against communism, papal encyclicals of the 1930s had condemned the Soviet Union as ‘the greatest existing threat to world peace and global Catholicism’ and sanctioned just war to defend religious and civil liberties against communist attacks (Chamedes Reference Chamedes2016, 276–277, 284–286).

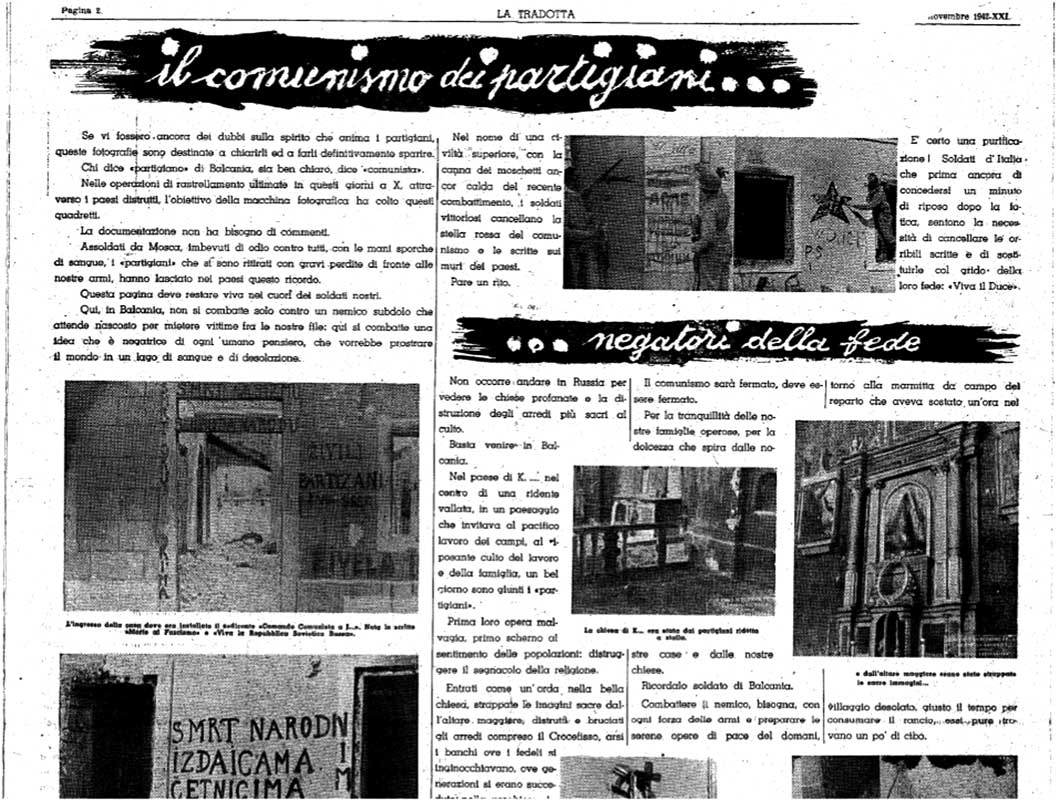

Italian military propaganda identified Balkan partisans with atheist communism, defining them as ‘deniers of faith’ (Figure 1). The ruined church became a recurring image in La Tradotta, as ‘proof of the sinister influence that Russia exerts from afar over Slav peoples, in the anti-European attempt to cast them into the arms of communism’ – the partisan ‘bandits’ fought ‘against all that is most sacred in earthly life, against God.’Footnote 12 Italian soldiers were reminded that ‘you don’t need to go to Russia to see desecrated churches and the destruction of religious ornaments. Just come to the Balkans.’ Propaganda juxtaposed the communism of the partisan against the civiltà of the crusading Italian soldier, who fought ‘for the peace and mind of our hard-working families, and for the sweetness that comes from our homes and our churches.’Footnote 13

Figure 1 ‘Il comunismo dei partigiani’, La Tradotta del Fronte Giulio, 8 November 1942, 2. Fondazione Museo Storico del Trentino - Emeroteca, Trento.

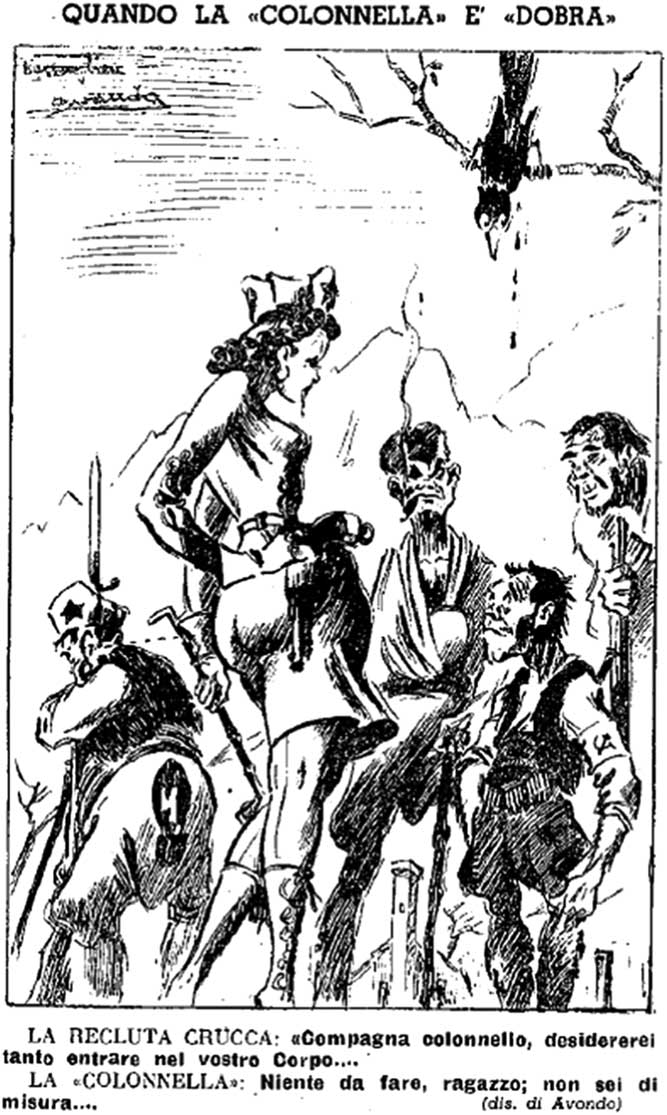

Another recurring theme was that of the ‘komesarica’, the female partisan (depicted in Figure 2). The alleged ‘inhuman insensitivity’ and cruelty of ‘partisan women’ contrasted with Fascist and Catholic notions of femininity and motherhood (De Grazia Reference De Grazia1992).Footnote 14 One story in La Tradotta told of a woman who threw a grenade at Italian soldiers while they searched her house, succeeding only in killing her own daughter. The soldiers in the story broke down in tears, unable to comprehend ‘the terrible deed’. The woman in the author’s eyes became only a communist: ‘she is no longer a mother’.Footnote 15 The model Italian soldier presented in these examples was less a battle-hardened and racially conscious Fascist ‘new man’ than a representative of pan-European Christianity and defender of traditional religious faith and family who recoiled from the inhuman and hateful ideology of communism.

Figure 2 Avondo, ‘Quando la “colonnella” è “dobra”’, La Tradotta del Fronte Giulio, 29 November 1942, 4. Fondazione Museo Storico del Trentino - Emeroteca, Trento.

Nonetheless, military propagandists connected the communist and anti-Christian nature of the partisan enemy to racial stereotypes about Balkan Slavs. Drawing upon the legacy of Border Fascism, the army defined communism and Slavism as non-European, inferior, and menacing. These ideas merged with a deep-rooted European conceptualisation of the Balkans as a primitive, tribal, and barbaric place (Todorova Reference Todorova2009, 3). In their official reports, Italian generals explained the resistance they faced as a reflection of the lack of civilisation of the local population, who were ‘by tradition, instinct, a Balkan people’.Footnote 16 In his postwar memoirs, the Second Army’s former commander, General Mario Roatta, reiterated his conviction that communism ‘exerted great fascination among the Slav populations of the Balkans’ (Roatta Reference Roatta1946, 173). Propaganda reflected the views of the military leadership, describing the communist red star worn by partisans as a ‘symbol of Asiatic barbarity’ and identifying communist ideas with ‘Asiatic philosophies’.Footnote 17 Atrocity propaganda demonised partisans in racial terms, explaining that in the Balkans ‘human flesh has as much value as tree bark. … The execution [fucilazio] is for partisans a ritual associated with the primordial savage massacres customary to these barbarous and primitive people.’Footnote 18

Partisans were derogatively labelled crucchi, a term that had ethnic and linguistic origins, deriving from the Serbo-Croatian word for bread (kruh), and which after 1943 was applied by members of the Italian Resistance to describe their German enemies.Footnote 19 The crucchi invariably were portrayed as dirty and depraved.Footnote 20 These characteristics were not just ascribed to the partisans’ indoctrination with communist ideology, but also to their cultural and racial heritage. Irredentist propaganda at the turn of the century had labelled ‘uncouth’ (rozzi) Slavs as ‘brigands’ (Catalan Reference Catalan2015, 52). Adopting similar language decades later, writers for La Tradotta concluded that the ‘communist partisan’ reflected more broadly upon a ‘people that have nothing in common with us; filthy drunks, scoundrels, traitors that neither feel physical pain nor share the refinement of our race.’Footnote 21 Propagandists racially contrasted the ‘brigandage of the Slav partisan against the heroic chivalry of the Latin soldier’.Footnote 22 The form of racism displayed in La Tradotta tended to be more cultural-spiritual than biological, consistent with tendencies in pre-war Italian anti-Slavism. However, as Figure 2 demonstrates, Balkan Slavs also were portrayed as physically diminutive, and with non-European facial characteristics.

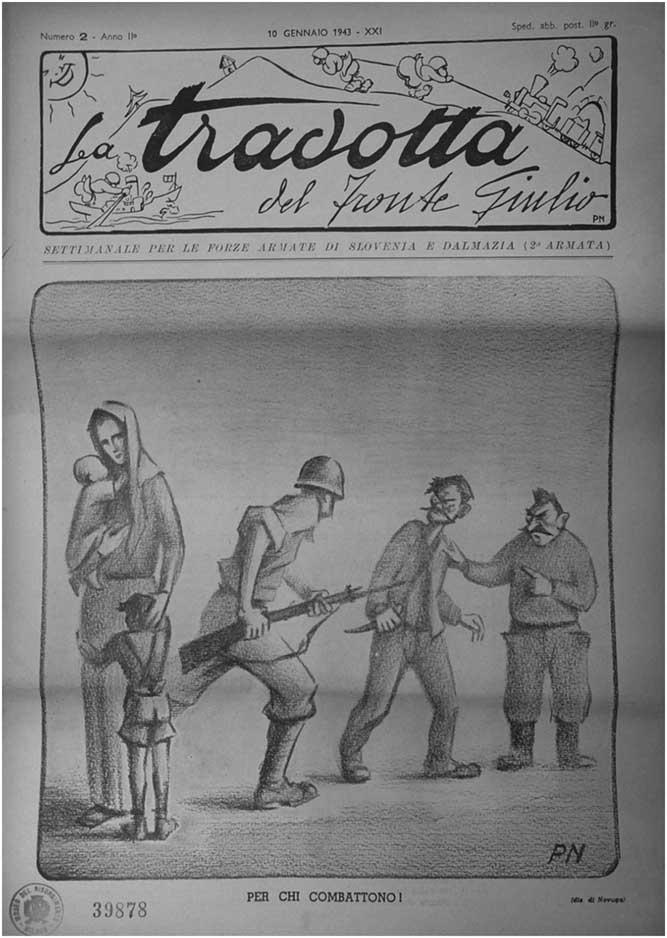

In Italian civilian propaganda during the war, Catholic rhetoric emphasising the communist threat to family values were usually distinct from the racist Othering that focused on the barbarism and savagery of Italy’s communist and Slavic enemies (Stone Reference Stone2008, 333–334). This distinction generally applied as well to the individual articles and drawings in La Tradotta, but the constant repetition of both Catholic and racist themes week after week created intersections. Sometimes, these intersections occurred within the same source. For example, Pietro Novaga’s cover art for the 10 January 1943 issue (Figure 3) blended the Catholic defence of the family with Fascist racial anti-communism. Novaga represented the Italian family through the familiar image of the Madonna and child, adding a second young boy who may be wearing a Fascist uniform. The communist partisan enemy, wielding an assassin’s blade, takes his orders from Stalin and bears the same racialised physical characteristics depicted in Figure 2. Anti-communism was the fulcrum around which Catholic views and nationalist-Fascist anti-Slavism converged.

Figure 3 Pietro Novaga, ‘Per chi combattono’, La Tradotta del Fronte Giulio, 10 January 1943, 1. © Comune di Milano - Palazzo Moriggia, Museo del Risorgimento, Milan.

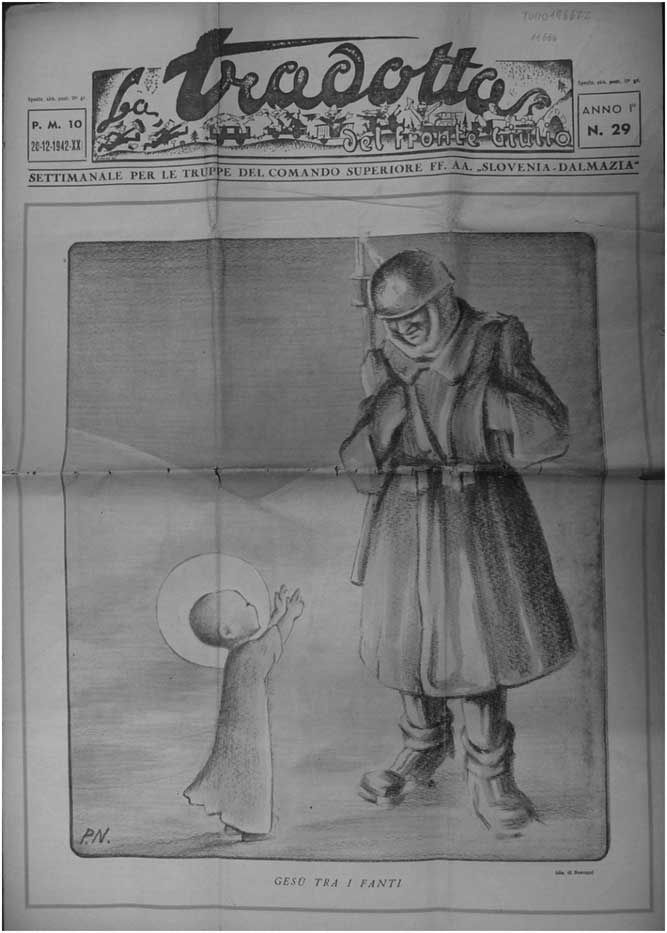

Figure 4 Pietro Novaga, ‘Gesù tra i fanti’, La Tradotta del Fronte Giulio, 20 December 1942, 1. © Comune di Milano - Palazzo Moriggia, Museo del Risorgimento, Milan.

Soldiers of Christ

Army propagandists did not use Catholic themes solely to inspire hatred for the enemy. They also adopted more generic or banal Christian imagery to justify the sacrifices made by Italian soldiers, in the process further defining Catholic spirituality as a key value of the ideal soldier and central component of his italianità. This reflected a broader late war trend in Fascist culture to adopt Catholic iconography in ‘a desperate search for a common language’ between Fascist and Catholic Italians (Zambenedetti Reference Zambenedetti2017, 177). It also demonstrated continuity with the First World War, in which the Italian army had provided soldiers with religious justification and meaning for their suffering, comparing their sacrifice to that of Christ (Morozzo Della Rocca Reference Morrozzo Della Rocca1980, 29–33). The primary objective of this category of propaganda was to comfort soldiers.

For example, Italian military personnel were supposed to be comforted to know that their families were praying for them. ‘You can lie down with these sweet thoughts until sleep comes,’ commented one author, ‘it does not matter that tomorrow there will be a long march, with tripod or machinegun on one’s back.’Footnote 23 Alongside faith in victory, religious piety would give soldiers the strength to perform the exhausting and monotonous work of counterguerrilla warfare under difficult environmental conditions. In some cases, propaganda reflected the superstitious or fantastical responses typical of rural peasants during the war (Malgeri Reference Malgeri1980, 12). A short article, which described Italians as ‘soldiers of Christ,’ claimed that the presence of a religious icon, a wooden crucifix, had prevented an Italian machinegun position from ever coming under enemy fire.Footnote 24 This did not correspond with the army and Fascism’s idealisation of soldiers yearning for combat.

Conventional religious references in La Tradotta were most common during holidays, such as Christmas and Easter. The Christmas 1942 edition began with a full-colour drawing of an Italian soldier in snow, the baby Jesus reaching up to him as if wanting to be held.Footnote 25 (Figure 4) The editorial on the second page praised the Italian soldier for his dutiful serenity in sacrificing a second Christmas to occupation ‘in a foreign land among foreign people’.Footnote 26 Half of the third page was taken up by a literary piece describing Christmas mass in an isolated southern Italian mountain village. The author described the sight of peasants on their way to church as ‘a great human Nativity scene’. The article emphasised humility and meekness, reminding soldiers that, like them, Christ ‘sleeps on straw, he doesn’t complain’.Footnote 27 A more secular cartoon depicted a soldier’s fantasy of a perfect Christmas, including scantily clad dancers, liquor, and fine dining. But, even here, the fantasy centred around Catholic mass ‘in a beautiful heated church’.Footnote 28 Representations of Italian soldiers as devout and humble Catholics, reliant on faith and prayer for strength and safety in challenging geographic, environmental, and combat conditions, indirectly complemented propaganda efforts to juxtapose Italians against godless communist partisans. On the other hand, they contradicted the traits of aggression and ruthlessness that both the Fascist and military leadership desired.

Christian fraternity

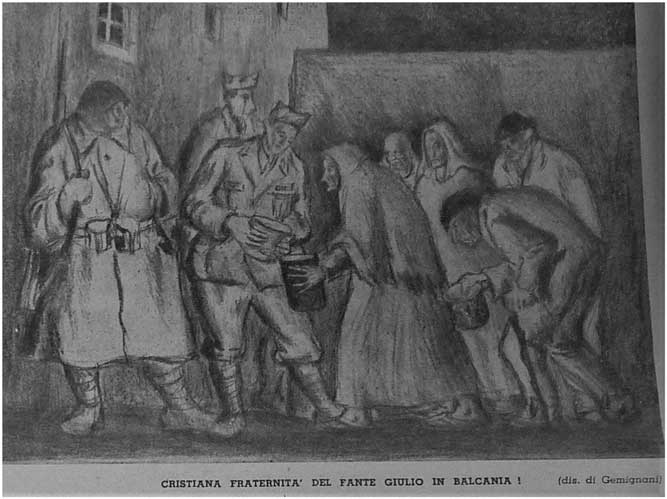

Propaganda appealing to the grassroots religiosity of the Catholic peasant soldier fed into a third distinct theme emphasising his supposed humanitarian instincts, which further challenged the army and regime’s versions of the ideal new man. Not infrequently, La Tradotta depicted Italian soldiers assisting the impoverished local populations with acts of charity. Images of strong and masculine soldiers doling out food rations to elderly, frail, and submissive Balkan Slavs certainly implied a sense of racial superiority. However, the caption in Figure 5 explained the army’s generosity as the result of the Italian soldier’s sense of ‘Christian fraternity’.Footnote 29 Military propagandists appealed directly to the Church’s universal mission of humanitarianism, which the Vatican had embraced since the end of the nineteenth century (Green Reference Green2017, 35).

Figure 5 Gemignani, ‘Cristiana fraternità del fante Giulio in Balcania!’, La Tradotta del Fronte Giulio, 21 March 1943, 2. © Comune di Milano - Palazzo Moriggia, Museo del Risorgimento, Milan.

Propaganda on the good deeds of Italian troops abroad was not unusual at the home front or directed towards international audiences (Stone Reference Stone2010, 70). However, it sent conflicting messages to soldiers who were meant to exemplify the regime’s concept of the Fascist new man as a racially conscious, severe, conquering warrior. Mussolini and Fascism reviled humanitarianism as bourgeois and ‘unmanly’ (Patriarca Reference Patriarca2010, 144). Earlier in the war, Fascist censors had condemned Catholic writing on charity for failing to conform ‘with the spirit of martial Italy’ (Ceci Reference Ceci2017, 269). Humanitarian propaganda also contradicted the army’s warnings against fraternisation with the local populations (Legnani Reference Legnani1998, 159). During the large-scale anti-partisan operations of 1942, Italian commanders presented the entire population as hostile, erasing distinctions between combatants and non-combatants, who were subjected to violent and indiscriminate reprisals (Osti Guerrazzi Reference Osti Guerrazzi2011, 91). According to Italian situation reports, relations with the occupied populations were ‘always limited and imbued with distrust’.Footnote 30 Although the Italian Second Army did distribute food to Yugoslav civilians, this policy was closely connected to the anti-partisan struggle (Hodzic Reference Hodzic2011, 384). The army weaponised food by withholding rations from populations that supported the partisans, a strategy that La Tradotta publicised as a ‘sound measure’.Footnote 31

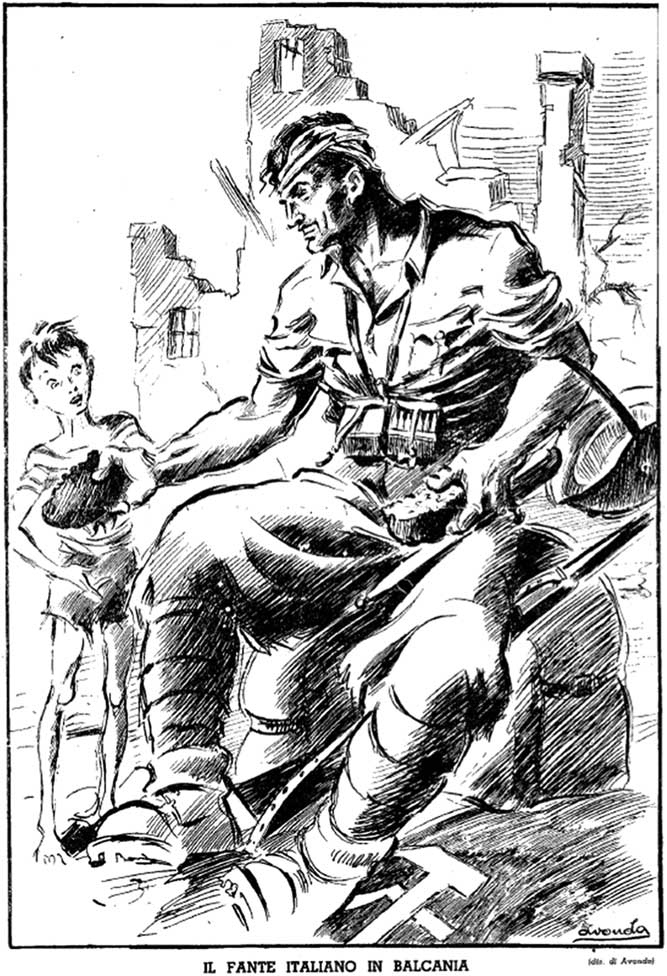

Military propagandists recognised the contradictions within their representations of Balkan Slavs either as uniformly hostile savages responding only to force or as innocent victims of communism in need of charity, and of Italian soldiers either as unfeeling standard-bearers of a warrior race or as compassionate and generous members of a Christian fraternity. Falling back on concepts of Italy’s superior Latin civilisation, an article in La Tradotta feebly claimed that Italian soldiers were ‘sufficiently great and civilised and strong in arms to feed an innocent child, and to destroy without mercy and to the last man those who prove themselves enemies of Rome.’Footnote 32 The war artist, Avondo – a professional illustrator who had produced anti-bourgeois propaganda for the regime in the 1930s (Falasca-Zamponi Reference Falasca-Zamponi1997, 112) – attempted to combine Fascist themes of racial superiority, masculinity, anti-communism, and imperial romanità with those of Catholic charity in his drawing of a larger-than-life soldier, with hammer and sickle under his boot, handing bread to a scrawny, ill-clothed, and wide-eyed boy (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Avondo, ‘Il fante italiano in Balcania’, La Tradotta del Fronte Giulio, 29 November 1942, 1. Fondazione Museo Storico del Trentino - Emeroteca, Trento.

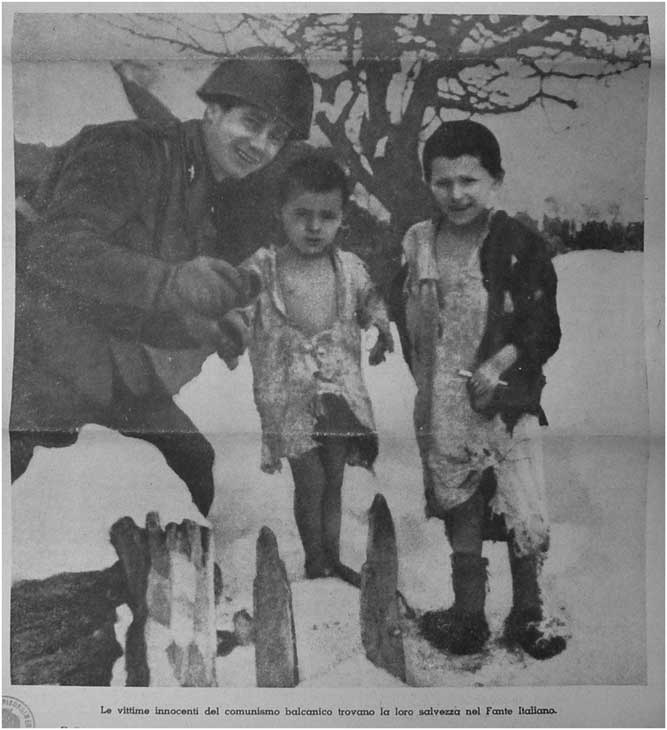

Other representations of the army’s humanitarian efforts lacked strong ideological components. The photograph of an Italian soldier with two children depicted on the first page of a March 1943 issue (Figure 7) adopted stylistic devices more common to international humanitarian imagery, itself strongly influenced by Christian precepts and morality (Fehrenbach and Rodogno Reference Fehrenbach and Rodogno2016). The focal point of the image is the two children; the photograph solicits an emotional response of pity. Off to one side, the smiling soldier lowers himself to the same level as the children. Only the caption, describing the children as ‘innocent victims of Balkan communism’, politicises the image. Towards the end of the war, the pages of La Tradotta oscillated between propaganda upholding Catholic goodness or charity and propaganda idealising Fascist violence or racialised hatred. In June 1943, the newspaper proclaimed that Italian ‘soldiers are good’ and promoted their ‘generous charity’ towards Yugoslav children, only to follow up a month later by reiterating Roatta’s maxim that the ‘good Italian’ was a ‘myth to explode’.Footnote 33

Figure 7 La Tradotta del Fronte Giulio, 28 March 1943, 1. © Comune di Milano - Palazzo Moriggia, Museo del Risorgimento, Milan.

Conclusion

The pages of La Tradotta reveal a ‘negotiation of religious and national identity’ (Faulkner Rossi Reference Faulkner Rossi2015, 11) that occurred during the war not merely at the personal level among individual Italian Catholics, but at the official level of military propaganda. The two identities, intertwined as they were by two decades of Catholic-Fascist discourse, co-existed uneasily in the army’s propaganda. Catholic anti-communism and Fascist anti-Slavism intersected relatively naturally in depictions meant to demonise Yugoslav partisans as enemies of faith and family. However, in other instances, the intersections between Catholicism, Fascism, and military culture did not work seamlessly. Representations of the conventional piety of Italian soldiers served military ends of promoting obedience and toleration of suffering, but they contradicted the ideals of aggression and love of combat that army and regime sought to impart. Praise of the Italian soldier’s humanitarian instincts and Christian sense of fraternity challenged concepts of masculinity and exclusionary ethno-nationalism shared by Fascist and military leaders. Although both Fascism and Catholicism shared values of discipline, obedience to authority, courage, and sacrifice, the ideal Catholic soldier was chivalrous whereas the Fascist version was pitiless (Dagnino Reference Dagnino2017, 198).

Military propagandists did not offer a viable synthesis of these conflicting identities and themes. They merely claimed that the Italian infantryman could himself represent a bit of ‘everything’.Footnote 34 The inconsistencies and contradictions within the Italian army’s propaganda reflected the challenges faced by propaganda officers tasked with maintaining institutional self-esteem in a losing war. The Second Army’s Propaganda Office tried to appeal to all types of military personnel – professional and amateur officers, logistical personnel, young combat troops, older reservists – through a single broadsheet weekly. Thus, representations of conventional Catholic piety co-existed with ideological and racist Othering, and with less politicised but licentious images of women that earned the newspaper official censure from the army’s top chaplain, Archbishop Angelo Bartolomasi (Franzinelli Reference Franzinelli1991, 77). As in 1918, the tug of war between central objectives and lower-level realities resulted in propagandistic content characterised by ‘contamination, eclecticism, [and] accumulation’ (Isnenghi 1977, 161).

The prevalence of Catholic themes in the Italian army’s propaganda was, then, partly a response to pressure from below. Grassroots Catholicism remained strong among the army’s peasant conscript soldiers. Many turned to religion and to military chaplains rather than Fascist imperial myths and propaganda to make sense of their war (Malgeri Reference Malgeri1980; Franzinelli Reference Franzinelli1991, 43–44; Pollard Reference Pollard2008, 101–105). Indeed, anti-communism – the area of greatest overlap between Fascist and Catholic views on the war – was the only recurring political theme in the correspondence of Italian soldiers serving in Yugoslavia (Manca Reference Manca2006, 124). As a desperate attempt to find common ground with the rank and file, the army’s appeal to Catholic religiosity reflected the failure of the Fascist project to transform ordinary Italians. As with late-war domestic film propaganda, ‘the regime turned to pre-Fascist loyalties and connections to faith and family’ in its appeals to Italian unity (Stone Reference Stone2012b, 132).

On the other hand, the convergence of Fascism, nationalism, irredentism, racism, anti-communism, humanitarianism, and Catholicism in La Tradotta complemented efforts of various groups inside and outside the regime to synthesise these contrasting worldviews (Pollard Reference Pollard2007, Aramini Reference Aramini2015). Military propaganda incorporated aspects of a ‘National Catholic’ identity that had developed with and through Fascism – based on an equation of the Italian Catholic nation with Roman and Italic civilisation – but that increasingly diverged from the Fascist model of italianità during the Second World War (Moro Reference Moro1988a, 85–86; Logan Reference Logan1997, 61–63; Traniello Reference Traniello2007, 260–262, 282). The idea of a ‘latent Catholic hegemony’ in Italy survived Fascism and provided the basis for Italian Christian Democracy and the catholicisation of civic culture in the post-war Republic (Moro Reference Moro1988b, 713; Ventresca Reference Ventresca2004, 271).

Catholicism also provided one of the ‘cornerstones’ for the myth of italiani brava gente, which was at ‘the core of Italy’s political and cultural redemption following World War Two’ (Lichtner Reference Lichtner2013, 174–176). The notion that the Italian people and their institutions remained fundamentally ‘good’ and humane through the Fascist years provided the ‘master narrative’ that dominated public memory of the war and national identity in subsequent decades (Focardi Reference Focardi2013). The Catholic and humanitarian themes present in La Tradotta del Fronte Giulio reveal that the brava gente myth had roots before the final collapse of Fascism, in the Italian army’s efforts to mobilise its troops to defend the Fascist regime’s imperial conquests in the Balkans. In the process of developing its multifaceted representations of the Italian soldier and nation, and at the same time as it justified atrocities and war crimes by vilifying enemy insurgents and populations, Italian military propaganda sowed the seeds of the brava gente myth.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Valeria Deplano, Silvana Patriarca, and the referees for their very helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article. For their help with image reproductions and permissions, special thanks go to Caterina Tomasi at the Museo storico del Trentino and to Ilaria De Palma and Paola Mazza at the Museo del Risorgimento in Milan. I also thank Michelangelo Pepe and Robert Ventresca for their important contributions to this project. Research funding was provided by a Doctoral Fellowship through the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

Nicolas G. Virtue teaches History at King’s University College at Western University in London, Ontario, Canada. He received his PhD from Western University in 2017. His dissertation, ‘Royal Army, Fascist Empire’ examined the relationship between the Royal Italian Army and Fascist empire-building in Africa and Europe.