‘Passerà anche questa stazione senza far male. Passerà questa pioggia sottile come passa il dolore’ (Fabrizio De André, Hotel Supramonte).

Introduction

This article revisits Italy's dramatic era of kidnapping for ransom that ran from the late 1960s to the mid 1990s, with kidnappings by the ’Ndrangheta our main focus. The work has two main objectives: first, we want to offer a fresh overall description of the phenomenon based on the analysis of a newly constructed database regarding the kidnappings; second, drawing on this analysis and an important case study, the abduction of Cesare Casella, we formulate a ‘political science’ interpretation of the final phase of these criminal activities.

Two particular limitations of the historical, sociological, and political science literature on kidnapping have helped us to determine our objectives.Footnote 1 The first relates to the difficulty in gaining an overall empirical picture of the phenomenon. There is no shortage of historical reconstructions (see Ciconte Reference Ciconte and Violante1997 in particular), reports by journalists (see Moroni Reference Moroni1993 and Veltri Reference Veltri2019, for example), tales of ’Ndrangheta victims (notably, Sergi Reference Sergi1991 and Chirico and Magro Reference Chirico and Magro2010), accounts by members and former members of the police forces and criminologists (including Fera Reference Fera1986 and Casalunga Reference Casalunga2013 in particular), and also descriptions by the kidnapping victims themselves (mostly as interviews). However, these various contributions present and discuss data – from governmental and police sources in particular – which have not previously been organised into a database that would assist subsequent research. It appeared necessary to construct such a resource, so that we could examine the trends in ’Ndrangheta kidnapping and, in particular, analyse its phase of decline, which has been the focus of our enquiry. Why give this our especial attention? Study of the Casella case, which belongs in the final phase of the kidnapping era, raised questions that differed from the prevailing concerns. The fact that the victim was held for a sustained period, amidst other very long kidnappings, prompted us to explore the trend in lengths of ’Ndrangheta abductions and how this might be explained. Dissent and conflict between official bodies over the management of this case seemed to be an important feature that merited investigation. In observing that the change in political climate and public opinion must have had a significant impact, we wondered how, and on what, its effects were felt.

The second limitation apparent in the literature relates to the interpretative keys. The prevalent concerns of the existing literature have not been those of political science; the main focus has been either judicial and legislative (see, for example, Brunelli Reference Brunelli1995) or criminological (see the two volumes by Luberto and Manganelli Reference Luberto and Manganelli1984, Reference Luberto and Manganelli1990). This is not to say that political factors are missing from the perspective: quite the contrary, in that the state is a protagonist in the arena, formulating objectives, producing laws, delineating crimes, and taking practical action against kidnapping. The behaviour and strategies of mafia members are also frequent interpretative keys, both in the literature mentioned above and in sociological work (for example, Arlacchi Reference Arlacchi2007). In addition, a section of the literature relates to the perspective of the victims of violence (Rudas, Pintor and Mascia Reference Rudas, Pintor, Mascia and Marongiu2004, for example). Taken as a whole, this literature offers many analytical starting points which connect different themes and topics.Footnote 2 However – and this is the limitation that has been our stimulus – the practice of politics itself, including inter-party electoral competition, has not been presented as a primary explanation for the trajectory taken by kidnapping activity, other than in occasional items of press coverage; it has instead been seen as an entirely secondary factor.

The issues that the literature explores include the reasons why the practice of kidnapping started and developed, and why it came to an end. The framework for investigation relates to the strategies of both the mafia and the state. In this regard, the most respected literature has identified the primary explanation, and the most straightforward, as the income that the mafiosi expected to generate through kidnappings. Authors have estimated the amount of ransom money paid: Enzo Ciconte, for example, claims that this had totalled ‘several hundred billion [lire]’ (1997, 208).Footnote 3 According to Ciconte, but also in the analysis of Pino Arlacchi (Reference Arlacchi2007, 99) and – with respect to the Corleone mafia – John Dickie (Reference Dickie2004, 356), this money served as a form of ‘capital accumulation’; in Calabria in the 1970s, for example, it was subsequently invested in the field of private construction and used for the purchase of vehicles and equipment so that the gangs could compete for major public works contracts. It has been argued that the money that came from kidnapping, alongside the earnings from contracts, was then used to enter the international drugs trade (Ciconte Reference Ciconte1992, 325–326; 1997, 203; 2013, 457; Arlacchi Reference Arlacchi2007, 153; Paoli Reference Paoli2003, 145). While kidnapping served this financial purpose, it also allowed the ’Ndrangheta's members to pursue objectives of political power (Sciarrone Reference Sciarrone2006; Stoppino 2011). In particular, they were concerned with the exercise of territorial control, and with the reputation that would allow them to maintain this. This reputation gave them greater credibility in the exercise of all other powers: it aided the extraction of further resources and could promote compliance (forcing people to surrender to requests for protection payments, speeding up agreements and the exchange of favours, and so on). Very brief kidnappings could also serve this purpose: they might, for example, break the will of an entrepreneur who had not wanted to go into business with them, or an owner of some land who was reluctant to sell (Ciconte Reference Ciconte and Violante1997, 200–01). The principal motives that led mafiosi into kidnapping also included conflict within the criminal world, and especially the desire to silence or punish people who cooperated with the law, as illustrated by the tragic kidnapping of the teenager Giuseppe Di Matteo, or their enemies, as in the kidnap and murder of Nino Salvo's father-in-law (Lupo Reference Lupo2018, 260). In some cases, kidnappings also served to divert the resources of the forces of order away from the locations where criminal groups were involved in much more important and remunerative activities, such as drug trafficking (Ciconte Reference Ciconte, Mareso and Pepino2013, 458). Finally, a secondary objective of kidnappings was to keep the channels open for communication with the state machinery on other fronts.

There seems to have been more interest in the reasons why the mafiosi abandoned kidnapping, in the mid 1990s, than in the reasons why a phenomenon of such extraordinary proportions had developed. The explanations have been developed by those working to combat this crime, who fall into two categories: magistrates and members of law enforcement agencies, who follow legal channels; and politicians serving on bodies charged with investigating mafia activity, or kidnapping in particular, such as the parliamentary Antimafia Commission. The nature of their formal roles has in fact led these people to ask themselves why the kidnappings ended. It was of course the responsibility of the relevant parliamentary commissions to draft legislation aimed at eliminating kidnapping; after it had been introduced, they needed to assess its operability and effectiveness. The specific issue of whether freezing the assets of the kidnap victim and their immediate family, an option introduced by Law no. 82 of 15 March 1991, had a significant impact on the incidence of the phenomenon was an obvious concern for the parliament that had approved the legislation. In the parliamentary environment, the expectation was that the pursuit of a policy on kidnapping would generate legislation that would, in turn, hasten the end of this phenomenon.

Those working to combat the mafia, criminologists, and mafia scholars have all been watching, very carefully, what they know well because of their profession: criminal activities and their mutation. As mentioned earlier, they have seen the ’Ndrangheta gangs, including some involved in kidnapping, becoming increasingly specialised from the late 1970s and through the 1980s in the international drugs trade, and the cocaine trade in particular. These observations have played an important part in the theory that a sort of cost-benefit analysis persuaded the mafiosi to pull out of the more risky and less remunerative practice of kidnapping. Explanations for the end of kidnapping, expressed very succinctly, give prominence to the roles played by two interconnected types of general factor: on the one hand, the increasing convenience, involving lesser risks, of the drugs trade and other criminal markets; on the other, the law passed in 1991, which increased the strength of deterrence. The primary interpreters of the issue, those directly involved in countering mafia activity, naturally ceased their analysis when the kidnapping era came to an end.

In our opinion, it is useful to attempt to reinterpret the final phase of the era of ’Ndrangheta kidnapping with additional keys that differ from the established ones, putting the social and political transformations of the period to the fore. In this regard, we believe that after the killing of Aldo Moro the demand that the lives of kidnap victims be protected took on much greater importance in the competition between political parties. This interpretation is confirmed by a review of the contemporary newspapers and television broadcasts. Once political kidnappings had died down and Sardinian banditry had been defeated, kidnappings by the ’Ndrangheta increasingly galvanised public debate under Italy's multi-party coalition government. The fall of the Berlin Wall, the ‘Tangentopoli’ bribes scandal and the mafia massacres of the early 1990s gave this government its coup de grâce; it was over the crime of ’Ndrangheta kidnapping that the party and government system demonstrated its inability to protect the lives of Italian citizens and mobilise support.

In the light of these reflections, this article investigates the final phase of ’Ndrangheta kidnapping and presents an interpretation that takes account of the decline of the old party system and the impact of political competition. In the section that follows, we draw on the new database to present the incidence of these kidnappings over time, their outcomes, and the trends in their duration. The statistical analysis also provides a backdrop for the kidnapping of Cesare Casella, our case study and the subject of the third section, which generated our early working hypotheses. Because this episode occurred near the end of the kidnapping era, and was especially drawn out, it is particularly relevant to our research objectives. On the basis of the overall picture that emerges from the statistical analysis in our second section and the case study in our third, in the fourth section we put forward some explanatory hypotheses on the end of the kidnappings that emphasise the importance of party politics and electoral competition, complementing the customary interpretative keys and enriching the debate.

A quantitative analysis of the kidnapping era

The database that underlies the analysis in this section was constructed from a range of sources that are in large part mutually consistent. The first set of data was kindly provided by the Ufficio Analisi, Programmi e Documentazione in the Department of Public Security, within the Ministry of the Interior. This source covers the period from 1972 to the present and includes the following information in relation to each case: location and date of the initial kidnapping; length of captivity; outcome; and number of people arrested. A second source is the work by Salvatore Luberto and Antonio Manganelli, published in two volumes (1984, 1990), which includes more information than the Ministry's data set and covers the period 1968–89. The information reported in this study includes the number of ransoms paid and their overall total value; age, gender and occupation of the kidnap victim; age, gender, educational attainment, birth province and further information on the perpetrators; method of abduction and captivity; location of the victim's release; means of communication initiated; and still more. Unfortunately, the authors only present this interesting information in aggregate form; as a result, it has only been possible to collect detailed information on kidnapping cases and the victims’ characteristics from 1972 onwards. There is a substantial overlap between the information in these two volumes and that presented and discussed by Giuseppe Fera (Reference Fera1986) for the period 1972–85. The Relazione sui sequestri di persona a scopo di estorsione, produced by the parliamentary Antimafia Commission in 1998 and reproduced in an article by Sarah Mazzenzana (Reference Mazzenzana2017), also includes some crucial information on trends in the frequency of kidnapping and its geographical distribution. Finally, Luigi Casalunga (Reference Casalunga2013) presents both aggregate data on these quantitative features and brief reports on every kidnapping during the period 1973–2006.

While we used all these sources, it was principally integration of the information provided by Casalunga and the data from the Ministry of the Interior that enabled construction of the database, which represents a new and richer source in comparison with the others available. In particular, the accounts by Casalunga made it possible to distinguish the ’Ndrangheta kidnappings from the rest. His book organises the documentation in three parts: kidnappings by Sardinian groups in Sardinia; kidnappings by Sardinian groups in other Italian regions; and kidnappings by other organised criminal groups. With the information available on the regions where these abductions occurred, they can be subdivided into five categories: first, kidnappings undertaken by Sardinian gangs in Sardinia (of which there were 98); second, kidnappings by Sardinians but outside Sardinia (35); third, kidnappings in Calabria, and therefore predominantly by local criminal gangs, with a varying degree of organisation, and presumed to be related to the ’Ndrangheta (122); fourth, kidnappings by organised crime outside Sardinia and Calabria, but not by Calabrian or Sardinian gangs, whose perpetrators belonged to Cosa Nostra, the Camorra and the Sacra Corona Unita (73); and fifth, kidnappings by Calabrians outside Calabria, and therefore very probably by ’Ndrangheta members away from home (326). By putting together the third and fifth categories, covering activity by Calabrians both within and outside Calabria, we can create the set of kidnappings presumed to have been perpetrated specifically by the ’Ndrangheta.

Our analysis starts with the incidence of kidnappings over time, irrespective of the perpetrators (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Frequency per year of kidnappings for ransom in Italy, 1968–2012 (N=688)

Sources: Luberto and Manganelli (Reference Luberto and Manganelli1984) for the period 1968–71; thereafter, data from the Ministry for the Interior, interpreted by the authors.

The period for which adequate information is available starts in 1968, although there had been no shortage of kidnapping cases before this date (Ciconte Reference Ciconte and Violante1997, 188). The phenomenon became much more prominent in 1974, and remained so for about ten years: 511 kidnappings were clustered together in the period 1974–84, an average of 46 abductions per year, accounting for 74 per cent of the total of 688 between 1968 and 2012. The number of episodes was much lower between 1985 and 1994 (102, averaging ten per year), and then the phenomenon largely faded away in the years that followed.

When we look at the regional distribution of kidnappings, Lombardy led the rankings in absolute terms, with 162 cases, and then Calabria (122), with Sardinia (98) third. They were followed by Lazio (62), Piedmont (40), Veneto (33), Campania (27), Tuscany (26), Sicily (25), Puglia (21), and then the other regions. In regard to the big cities, Milan (with 53 cases) and Rome (46) were the worst hit, followed at some distance by Turin (18). After these three locations, the average-size cities and small towns of Sardinia and Calabria accounted for the higher numbers of cases.

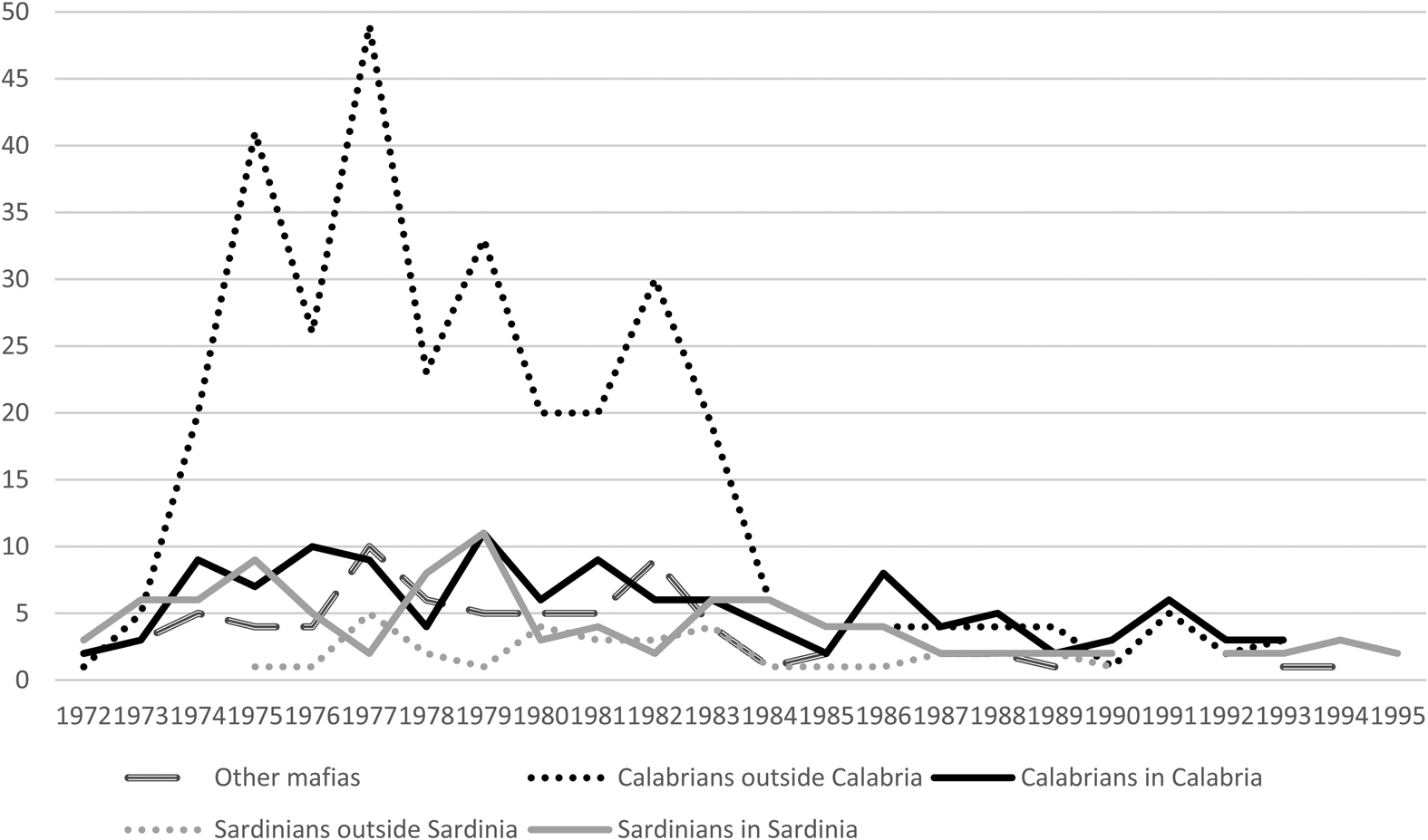

The trend over time for each of the five different categories of kidnapping distinguished earlier is presented in Figure 2, from which a fairly simple but very revealing picture emerges.Footnote 4 In comparison with a relatively consistent incidence over time for kidnappings by Sardinians, both within and outside Sardinia, and by other mafia gangs, both in their home regions and elsewhere, and also by Calabrians in Calabria, there was a rapid increase in the number of kidnappings by Calabrians outside Calabria, which reached an unprecedented peak and then stayed high for about ten years before dropping back to earlier levels.

Figure 2. Frequency per year of kidnappings by type of mafia gang, 1972–95 (N=645)

Sources for Figures 2–6: Luberto and Manganelli (Reference Luberto and Manganelli1984, Reference Luberto and Manganelli1990), Fera (Reference Fera1986), Casalunga (Reference Casalunga2013), and data from the Ministry for the Interior, interpreted by the authors.

A fuller understanding of the characteristics of the different categories of kidnapping is provided by investigation into its outcomes, some fatal for the victim and some not; this allows us to see whether its overall profile varies over time only in numbers, or whether its numerical expansion and contraction was accompanied by qualitative changes. In general terms, someone's abduction can end in the following ways: first, liberation of the hostage by the forces of order or other bodies; second, escape by the hostage, successfully evading their captors’ supervision; third, release of the hostage by the kidnappers; and fourth, killing of the hostage by the kidnappers, or their death for other reasons. In this last case, the body was sometimes recovered, and sometimes not. From the 654 kidnappings considered in total, in 41 cases the hostage managed to get away on their own (at least according to official documents), in 79 the kidnap victim died (with or without recovery of the body), in a further 94 the victim was liberated, and in the remaining 440 the kidnappers released their hostage.

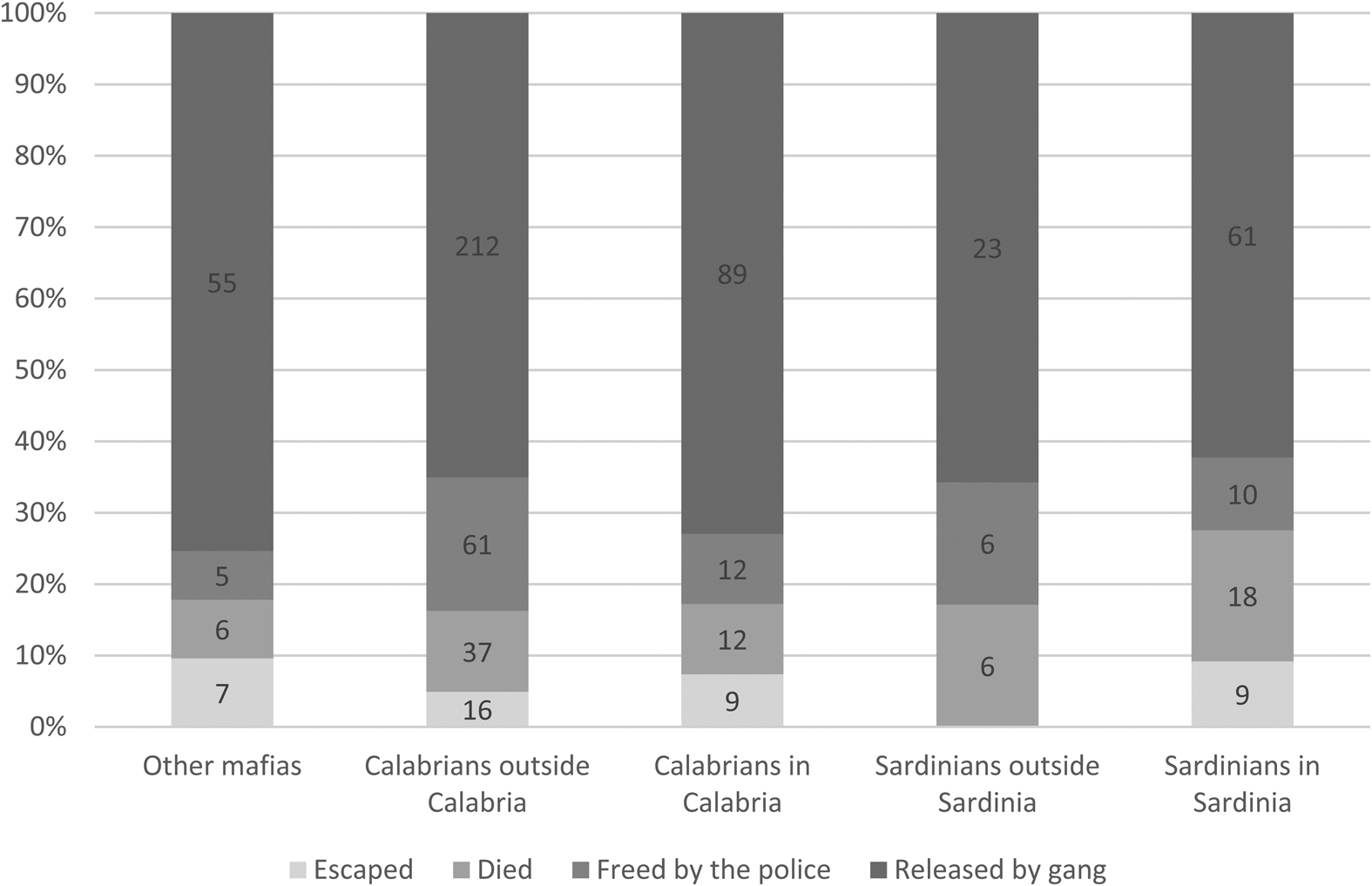

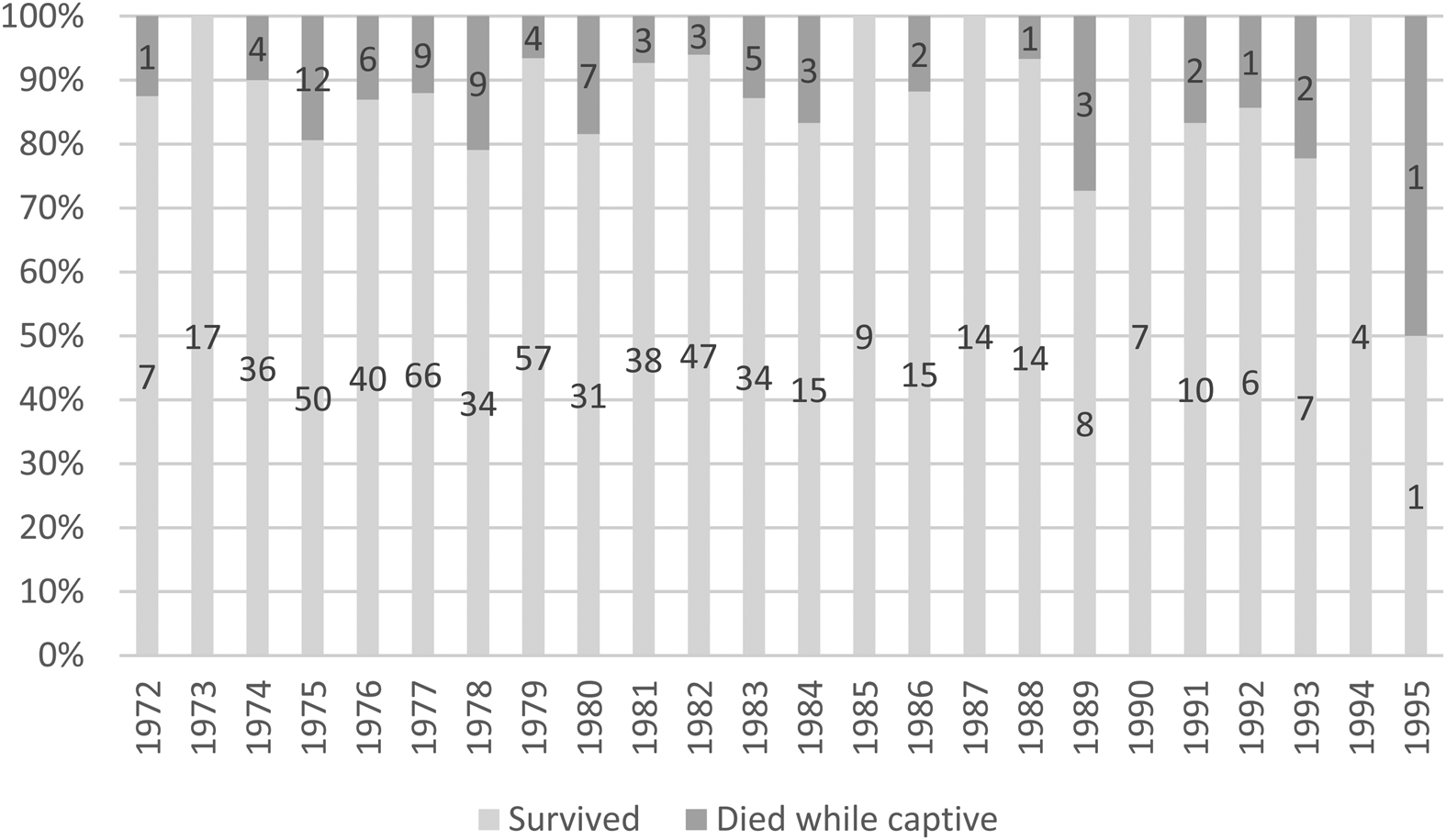

We now move on to investigate the relationship between the five different categories identified earlier and the different types of outcome, both when compared with each other and looked at over time. The different outcomes in relation to the categories of criminal group are presented in Figure 3, and kidnapping outcomes over time in Figure 4. In the latter case, to make the visual presentation easier to interpret, the potential outcomes have been grouped in just two categories: those in which the hostage survived (whether escaped, liberated or released), and those in which they did not. This distinction highlights the death rate connected with kidnapping.

Figure 3. Kidnapping outcomes by category of kidnappers, 1972–2012 (N=654)

Figure 4. Kidnapping outcomes each year by victim survival rate (%), 1972–95, also showing actual figures (N=645).

It can be seen from Figure 3 that kidnappings by Sardinians, both within and outside Sardinia, were associated with a higher death rate of the hostage. Next come the kidnappings by Calabrian gangs, with not much difference between the abductions in Calabria and those that took place elsewhere. The final outcomes of kidnappings by other mafias were on average mildly less fatal. When we look at the death rate over time, this does not seem to present any marked differences, leaving aside the brief spike in 1989. The proportion of kidnappings that ended in the victim being freed by law enforcement agencies was higher both for Sardinian gangs outside Sardinia and for Calabrian gangs outside Calabria; this may well have been due to the greater constraints on moving about and controlling the territories where they had established bases but were not on home ground. It may also have resulted from the greater logistical challenges of having to move people distances of over a thousand kilometres, as was the case for hostages abducted in northern Italian regions and then held captive in the Aspromonte area.

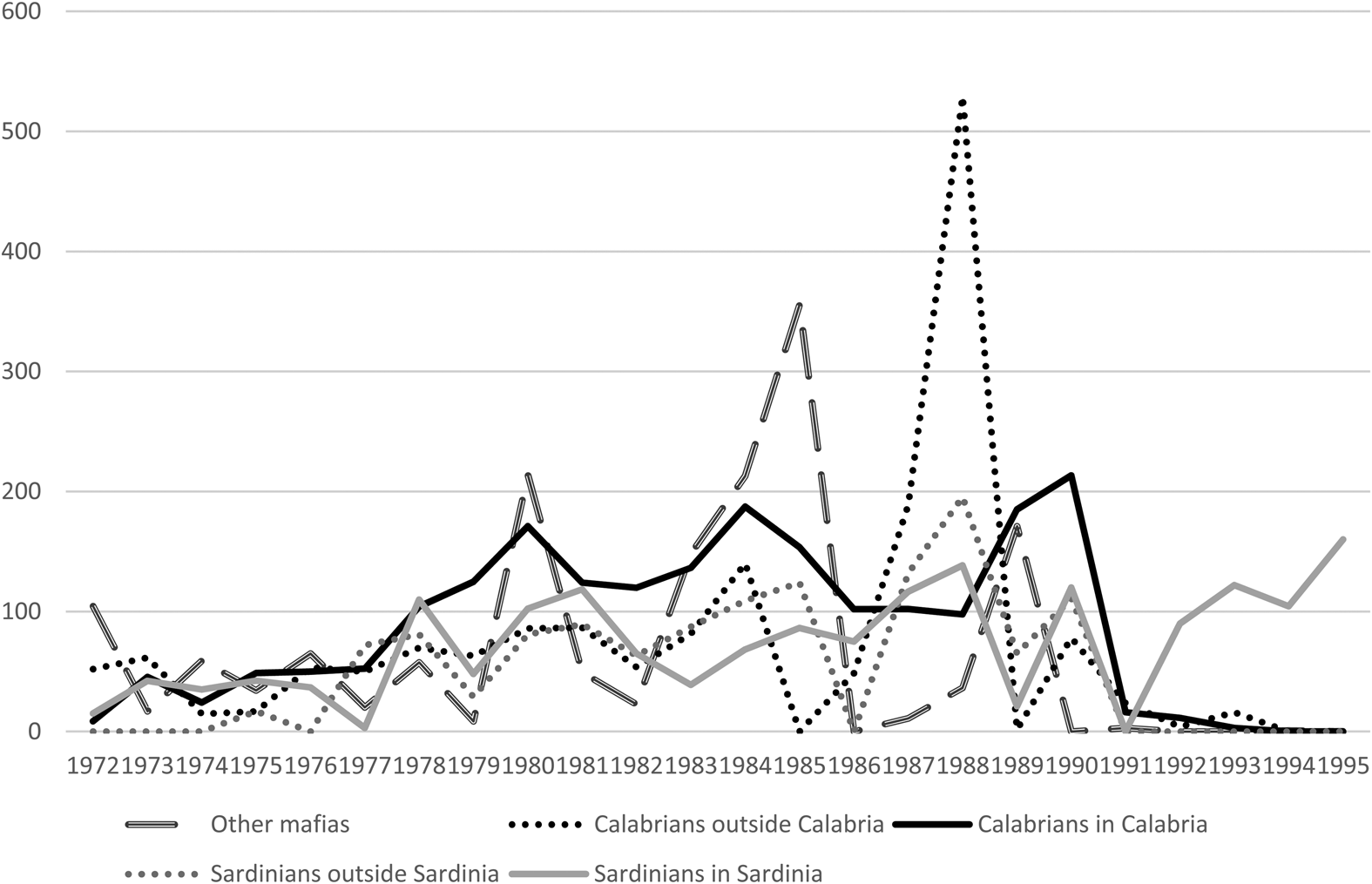

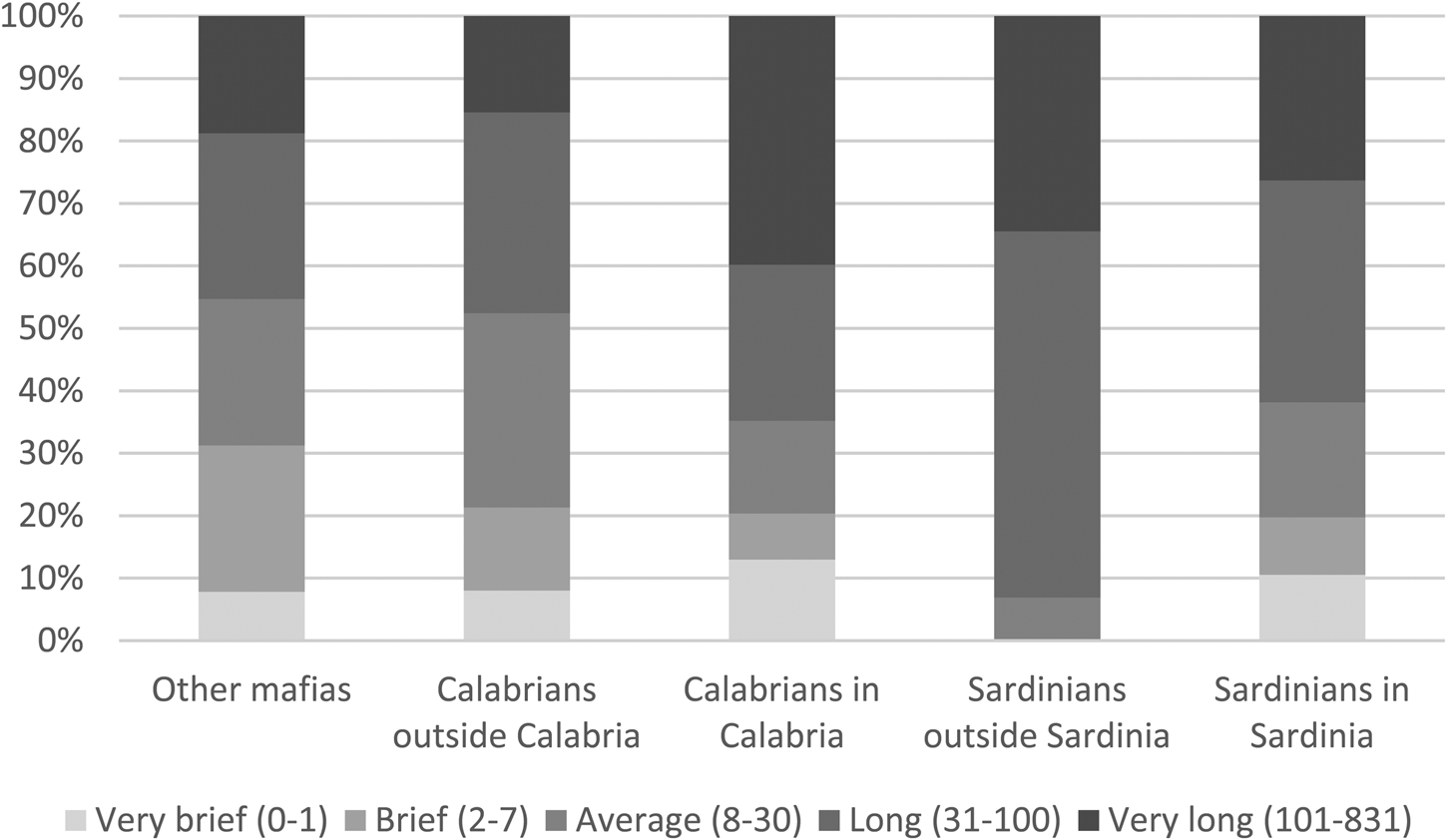

When we turn to the length of time that victims were held captive, it is apparent that this was subject to extreme variation. Kidnappings could be very brief, lasting only a matter of hours and concluding with the hostage's escape, liberation by the forces of order, or release by the kidnappers (because they had collected the ransom, or were being hunted down by the police); they could also be very long and exhausting periods of captivity that stretched out for more than two years. Table 1 uses five categories of duration to illustrate this variation, while the average lengths of kidnappings by the different types of gang, over time, is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Average length in days of kidnappings, by year and by type of gang, 1972–95 (N=563)

Table 1. Duration of kidnappings, and other outcomes, 1972–2012

The great variations in the practice of kidnapping are illustrated by the differences in duration of individual instances, presented in Table 1. Within these substantial differences, we can then try to identify patterns: the data presented in Figure 5 suggest two particular features. First, irrespective of the type of kidnapping gang, there was a significant increase over time in the average length of periods of captivity: it was clearly going up at the end of the 1970s, remained very high throughout the 1980s, and then fell back at the start of the 1990s. If we compare the data for the three decades, kidnappings lasted an average of 49 days in the 1970s, a much higher 99 days in the 1980s, and fell back to an average of 74 days in the 1990s. We discuss the various possible explanations for the increased average length during the 1980s later in the article. The second feature apparent in Figure 5, which is explored further in Figure 6, is that lengths of kidnapping vary according to the different categories of gang. Calabrian gangs that were operating in Calabria stand out both for the higher proportion of very long kidnappings and, in contrast, for the higher proportion of very brief ones. The Sardinian gangs operating outside Sardinia, on the other hand, never undertook very brief or brief kidnappings. However, the most striking feature of all is the dramatic increase in the average length of kidnappings by ’Ndrangheta gangs operating outside Calabria in the late 1980s. This seems to reflect a change in strategy at that point by these particular groups, who were able and willing to keep hostages in captivity for periods that to them must have seemed never-ending.

Figure 6. Length of kidnapping by type of mafia gang, 1972–2012 (N=563)

This brief comparative and longitudinal analysis of the different types of kidnapping highlights two features that distinguish the abductions by ’Ndrangheta gangs: their primacy both in the export of the practice of kidnapping outside their home region of Calabria, and in the length of their victims’ captivity in the final period of the kidnapping era.

The Casella case and the final period of kidnapping

The Casella abduction, which lasted from January 1988 until January 1990, took place at a turning point for the phenomenon of ’Ndrangheta kidnappings. During this period, which included the other longer abductions,Footnote 5 their annual frequency was on the downward slope from its peak but their average duration was increasing. The case study allows us to look close up at our key object of enquiry – the decline of this criminal activity – but also at the possible explanatory factors that relate to the political environment. While this kidnapping was under way the Berlin Wall fell and the established international order broke up; within Italy, the traditional party system was on the verge of disintegration and the governing political class about to be put in the dock. In brief, kidnapping was burning out during the period when Italy's ‘First Republic’ was coming to an end. In this complex and uncertain picture two elements, we believe, made a direct contribution to the end of kidnapping. The first was a change in the style and nature of media coverage, which had obvious effects on the formation of public opinion and people's motivation to take action on this issue. The result was an increasing politicisation of this crime. The second, which we discuss later but not at the same level of detail, was the behaviour of the law enforcement system.

In regard to the change in media coverage, it should first be said that the degree of visibility of any aspect of mafia activity relates to at least two issues: the extent to which it is clearly action by the mafia and acknowledged as such, and the size of the audience commanded by the person who identifies and condemns it. Once kidnapping had become visible in society, it also became a political issue: the demand for it to be managed started to play a part in political competition, featured in election campaigns, and exerted pressure on the institutions of government. These, in turn, showed a greater interest in generating action and policies to counter this crime, in order to demonstrate their own effectiveness. Bearing this in mind, we now examine the way that the visibility of kidnapping increased with the Casella abduction, which therefore represented a turning point.

Kidnapping was more visible than other mafia practices because it was more violent. When compared with the extortion of protection money – sometimes the precursor to an abduction – kidnapping's primary ‘basis of power’ (Stoppino Reference Stoppino2001) was the more overt threat to physical wellbeing. Mafia strength proved much more ‘invisible’ when degrees of expediency and acceptance, not just the fear of violence, were aspects of the victims’ experience, generating the complex motives behind ‘omertà’ (submissive silence). Kidnapping's visibility resulted from its complete unacceptability to victims and their families; almost all kidnappings were in fact reported.

An abduction became more visible when the hostage subsequently died. However, the visibility of such an act of bloodshed also depended on the general frequency of murders. Although there were fatalities in Calabria as a result of mafia kidnapping in the early 1970s, the phenomenon was still scarcely in the public eye because the region was already tormented by murders and mafia violence. Neither this specific type of crime, nor its perpetrators, nor even its victims were sufficiently ‘seen’. It only became more apparent when a ‘big hit’ was undertaken, outside the gang's home territory: the abduction of Paul Getty, the grandson of an American oil magnate, in Rome in 1973. Kidnapping and its perpetrators were then thrown into sharp relief. This leap forward in visibility also had a symbolic power, because the person seized in this instance was both very rich and foreign. Criminal organisations are involved in making money by using violence, but are also involved in fostering the narrative of kidnapping as a mechanism for the redistribution of wealth, aimed at public perceptions in their home territory. From the early 1970s onwards, ’Ndrangheta gangs were abducting businessmen in northern Italy, and counting on a myth of redistribution in these cases too. The kidnappings in the North that ended in murder emphasised the violence of this crime. Despite this, kidnapping still made relatively little impact on public consciousness during the 1970s. The expansion of kidnapping activity outside home territory and the kidnappings in the North that ended in murder did of course make the mafias more ‘visible’. The ’Ndrangheta then posed an additional challenge to the state by transferring its victims from northern Italy to the Aspromonte area. However, violence – both political and mafia-related – was such a widespread occurrence in Italy during the second half of the 1970s, reaching a historical peak and creating a climate of terror, that it rendered the specific practice of kidnapping unremarkable.

Systematic violence and the practice of kidnapping followed a similar trajectory. The peak in kidnapping activity did not correspond with either the height of its visibility in society or any specific effort to counter this phenomenon. The subsequent increased visibility of mafia kidnappings in part related to the weakening of the complex web of violence and criminal brotherhoods that had pervaded Italian history. Kidnappings only became very visible when they provided a tragic finale to the turbulent story of political violence within which they had proliferated.

During the period when political violence was on the wane, the competition between private television stations and state television (which was more politically controlled) was creating a public arena in which news events were increasingly presented as emotional spectacles. The different form of mediation helped to generate a different reaction from society to these events. One manifestation of this changed social reaction could be seen during the abduction of Marco Fiora, a young boy from Turin who was kidnapped in March 1987 and held captive for an extended period. A crowd of about ten thousand people came out onto the city's streets to ask that he be freed. The demand was unusually simple: liberation of the child, and nothing else. On the new style of television, it had even become possible for a well-known media personality, Adriano Celentano, to issue a direct appeal to the mafiosi (calling them ‘ragazzi’) in the course of a very popular programme, ‘Fantastico 8’. The quest for an audience to inflame created spectators for the crime. Space was finally awarded to empathy for the victims and their families. The spectators then became interested in all the protagonists of this criminal drama, and the spotlight fell on mafiosi as never before.

With the Casella kidnapping in 1988, this emotional form of media treatment reached its height. Moreover, there was a further development in the media's new practice of addressing mafia gangs directly. This case, which remained in the limelight of national reporting more than any other kidnapping, also broke through the web of support for the ’Ndrangheta in its home territory, because Angela Montagna, Cesare Casella's mother, tried to make links with villages in the Locride area, where it was presumed that he was being held, asking for the support of its mothers. In a photograph that attracted the attention of the national and international press, she was pictured in Locri's main piazza in chains representing her son's captivity. ‘Mamma coraggio’ (‘Mother Courage’), as the media would call her, fostered a simple but effective narrative: kidnapping's perpetrators seize and murder children, while mothers are made to suffer. The quest by Cesare's mother for human solidarity, including in areas close to those of the mafia, took place on the basis of this characterisation. This narrative simplification damaged the symbolic basis of mafia strength: kidnapping's basis of power was in danger of being stripped back to naked violence. At the same time, the striking and widely distributed image of a mother in chains was a direct slap in the face for the political institutions of government, which could no longer remain inactive without suffering a drop in popular and political support.

Impotence, uncertainty and the hardline approach of a ruling political class in eclipse

At the end of the 1980s, mafia kidnappings, which were in decline but more visible, were used as a powerful indictment of the local and national political classes by the media and civil society. Politicians were pushed into taking public positions. The political class found itself under scrutiny by television, accused of failing to protect the lives of citizens and depicted as impotent. An analysis of newspaper and television coverage during the extended period of the Casella kidnapping offers an eloquent picture of how politicians reacted.

In this atmosphere of increasing social pressure, two types of actor went on the attack against the government: the opposition parties and local authorities. There was an unprecedented mass resignation by the mayors of 42 municipalities on Calabria's Ionian side, who declared ‘a negative verdict on the action taken to date by the Ministers of the Interior, Defence and Justice […] in order to defeat the regrettable mafia phenomenon and re-establish the rule of law in our area’ (La Gazzetta del Sud, 15 June 1989). The main opposition party, the Italian Communist Party (PCI), mounted a harsh attack on the coalition government. The Minister of the Interior was subjected to tough questions in parliament (La Gazzetta del Sud, 14 June 1989). Accusations of ineffectiveness were supplemented by the charge of complicity with organised crime (La Repubblica, 14 June 1989). During the Casella kidnapping, Christian Democrat (DC) stalwarts held both the office of prime minister (first Ciriaco De Mita and then Giulio Andreotti) and Minister of the Interior (Antonio Gava, in both the De Mita and Andreotti governments). De Mita and the representatives of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) took an intransigent line; this led to a direct dispute with the Casella family, which they accused of compromising the case's potential resolution. Andreotti chose not to rebuke the family, but blamed both the mayors who had resigned and, at the same time, action taken by priests and bishops, accusing them of engaging in pointless and damaging acts of self-promotion rather than assisting the investigations. De Mita admitted that coordination between the various law enforcement agencies was weak. Andreotti proposed that Italy's three secret services should be unified, thus admitting that there were also issues of poor coordination on that front. The DC elite said ‘leave it to us’, and proposed new legislation and a new organisation. This was a weak strategy because it failed, firstly, to prevent further kidnappings and, secondly, to explain their previous and persistent inertia over measures that were now described as necessary and urgent, despite the longstanding nature of the problem.

When we look back now at everyday events of that time, it appears that the contemporary political class had no real inkling of the way in which it was to be swept away, but there was one thing that it seems to have understood very well: it was not just the scourge of kidnappings that was in play, but also the government, its coalition, and possibly the pre-eminent central party within the political system. The PCI had taken on a novel appearance, which had the features of Mikhail Gorbachev but also those of Gerardo Chiaromonte, the president of the new Antimafia Commission, and Michele Santoro, the presenter of ‘Samarcanda’, a popular weekly programme on the RAI 3 television channel. On one occasion this programme first featured ‘Mother Courage’ in the Locride area, saying that she would not be voting, and, shortly afterwards, people arguing that it was not appropriate for the bishops to urge Christians to vote for the DC. Moreover, new actors were appearing on the political stage and seemed capable of threatening the stability of the multi-party coalition arrangements. In particular, in April 1989 the mayor of Palermo, Leoluca Orlando, extended the membership of his majority coalition to the PCI while excluding the PSI and recalcitrant elements of the DC. With other emergent political actors, Orlando later went on to form ‘La Rete’ (‘The Network’), standing on a programme of combatting the mafia and challenging the establishment. Meanwhile, Umberto Bossi's Lombard League was building up momentum on the basis of a secessionist programme, which took an offensive and simplistic approach in accusing the Italian South of parasitism and central government of corruption. On the back of this, the Northern League was launched in December 1989. For the DC, two things were at stake with the ’Ndrangheta kidnappings in the North: first, the lives of those abducted, and second, the loss of power and support if the new political actors managed to force their way into the party system. In January 1990, its general secretary Arnaldo Forlani launched a furious attack on the Gozzini prison reform legislation, which had promoted rehabilitation; he even argued for the death penalty for kidnappers who committed murder (La Gazzetta del Sud, 5 January 1990). His statement drew praise from the neofascist Italian Social Movement and adverse reactions from opposition parties on the left and sections within the DC itself. The DC thus split into its customary factions, the time for its formal fragmentation having not yet arrived. Forlani's outburst had been unusually forthright, but very probably deliberate. The intention, also expressed within the PSI, was to clamp down hard on the perpetrators of this crime; it was hoped that this approach would not only induce the kidnappers to cease their activity but also retrieve the party's electoral support, both by facing up to the Northern League and by discomforting the PCI and the left-wing elements within the DC that were hoping for a new alliance with it. Action by the armed forces at Luino, thwarting an anticipated abduction and killing the entire gang before it could happen, provided a demonstration of the state's hard line, at least in the convincing interpretation of events offered by the Calabrian intellectual and journalist Pasquino Crupi (Reference Crupi1990). To demonstrate its effectiveness, the multi-party coalition government became an executioner.

At the end of the 1980s, mafia kidnappings were decreasing but still taking place, and their continued occurrence had become a severe and damaging political embarrassment. If the DC wanted to remain at the centre of the political system, kidnappings could not be ‘managed’ as they customarily had been, but needed to stop. It was a Christian Democracy at the end of the line that oversaw the finale to the period of ’Ndrangheta kidnappings, with the intention of bringing it to its conclusion.

The management of one of the final kidnappingsFootnote 6

Cesare Casella was abducted in January 1988, in Pavia, and was then held captive for longer than anyone apart from Carlo Celadon. After removal to the Aspromonte region he was held captive in three different places. The first ransom demand was for an exorbitant eight billion lire, which then went down to one billion.Footnote 7 This was paid by the family, through a representative, in the Locride area on the eve of the Ferragosto holiday in 1988. No release resulted from the payment of the billion lire, which the family were told to ‘consider as a first instalment’; instead, there was a demand for a further two billion lire, which rose in September to two and a half billion and was later, in June 1989, to reach five billion, only to be reduced back down to one billion.

After the first ransom payment had been made, the investigations were in the hands of a young magistrate in Pavia, Vincenzo Calia, who took responsibility for freezing the bank accounts of the victim's relatives before this measure had become a legal norm. In the summer of 1989, thanks to the visit by Cesare's mother Angela Montagna to the Locride area, the case became the focus of ongoing media attention. Contact between the kidnappers and the family had initially been intense, and were shared with the Ministry of the Interior, but gave way to a long silence; attempts to make a second ransom payment failed. The kidnapping had lasted a long time, and was stalled; it was in the spotlight, and was politically explosive. The magistrate decided to replace negotiations with armed action during the handover of a ransom payment, and with this in mind requested the collaboration of the police's Central Security Task Group (NOCS). The NOCS argued that the Aspromonte area was controlled by the kidnappers, and that this course of action was therefore not appropriate; they suggested payment of the second instalment. The magistrate, however, pursued his plan, asking for an expert assessment by the Special Action Group (GIS) within the Carabinieri regarding armed intervention. The GIS responded positively. The magistrate was in complete agreement with the GIS and the Carabinieri Central Command over all aspects of the operation, which was conducted in the strictest secrecy. The kidnappers eventually made contact, and established the type of vehicle and the go-between. On 20 December, they set out conditions for the payment. On Christmas Eve, they indicated the payment location. The plan got under way. While in transit, the designated car was switched for another one, identical but armoured and furnished with special equipment: it had flares, deafening sirens, one carabiniere in place of the agreed driver and another hidden in the boot. At the payment location, the three armed kidnappers were taken by surprise by the sonic devices and an exchange of fire. Giuseppe Strangio, a known mafia criminal, was wounded in the foot and captured.

In order to avoid the police's involvement at the location for armed action, and the related risks, the magistrate had committed them to hundreds of seizures and searches in Platì and San Luca on the same night. Nevertheless, the police and men from the police force's Anti-Kidnap Unit, unaware of the planned operation, responded to the gunfire at the scene. This created a palpable safety risk for the Carabinieri's plainclothes officers and forced a revision of the GIS plan, which had been aimed at the immediate liberation of Casella through Strangio and the subsequent recapture of this fugitive. Strangio was persuaded to collaborate and sent messages from prison directed at keeping the hostage alive. After the attack the newspapers described tense relations between the magistrate and the family, varying assessments by the judiciary on the appropriateness of the operation, and a dispute between the police and the Carabinieri (La Repubblica, 3 January 1990). On 30 January 1990, Cesare Casella managed to free himself from the stake he had been tied to, reached a house, and was taken to the nearby Carabinieri barracks (La Repubblica, 31 January 1990).

The theory that the collaborative venture between the magistrates and the GIS was not the only plan under way was supported by various features of the case, ranging from disclosures by the arrested ’Ndrangheta member to the discovery of ‘mediators’, as they described themselves, who were somehow involved. When the NOCS gave their opinion that armed action in the Aspromonte area was not viable, this may well have reflected a strategic vision of the action to take that was shared by the Ministry of the Interior, as well as the purely technical considerations. Furthermore, the political importance of the Casella case meant that it was highly unlikely that the Ministry and the security forces were doing nothing, although of course it has not been possible to find any cast-iron confirmation and to offer a proper account of covert state action.

This reconstruction has highlighted the lack of organisation across the different elements of state machinery, and has emphasised that investigations into the end of mafia kidnappings, at the beginning of the 1990s, would not be complete without studying the behaviour of the law enforcement system as a potential explanatory factor.

How did the kidnapping era end? A reinterpretation

In order to understand the terminal phase of this criminal trajectory, we need to return to the two interconnected types of motive mentioned in our introduction. On the one hand there was a new cost-benefit analysis by the ’Ndrangheta groups, whose elements included judicial penalties, deaths (as at Luino) and unwanted publicity. On the other there was a comprehensive response from the state, which had to take account of the changes under way in the political, social and media contexts. The law on freezing the assets of kidnap victims and their close family introduced in March 1991 was an overt policy measure. We need to look at two less open issues: the state's payment of ransoms, and strategic decisions taken in regard to law and order.

Prior to the law of 1991, and while the Casella kidnapping was ongoing, the decision to freeze a hostage's assets was at the discretion of individual magistrates rather than being compulsory and automatic. The magistrate could also take responsibility for a similar decision in relation to the victim's family, often shattering the relationship of trust in consequence. Families felt betrayed, and would seek other avenues for payment and mediation. They naturally also turned to the political class in the quest for guarantees about the lives of their loved ones. The approach taken by an individual magistrate may not always have been in line with the strategy and tactics – varying in visibility – pursued by other elements of the state machinery. Another law enforcement agency might have been focusing on the identification of informers or mediators in order to open a channel of communication that would eventually reach the kidnappers (Scaccia Reference Scaccia2000). On this issue, there is clearly no realistic expectation that the documents relating to state activities of mediation, or to the covert funds allocated for these purposes, will be made available or archived; it is therefore impossible to document in which cases state bodies used the money, and in what forms. In some criminal investigations a sort of relatively stable network, consisting of agents of the state, intermediaries and gang members, can be discerned, which operated to resolve kidnappings, or even prevent them, on payment (Scaccia Reference Scaccia2000).

The law of 1991 did not, therefore, solely relate to the freezing of family assets, but also dealt with the state's previous arrangements for paying informers and intermediaries for the release of ’Ndrangheta kidnap victims. The idea that after the new law was passed the state could have immediately reorganised matters is hardly consonant with events or with the nature of the issues in such a delicate area. The implementation of its key principles – shutting down the various means of making payments and, especially, closing the communication channels that reached the ’Ndrangheta – must have been difficult in practice. Furthermore, it is highly likely that ransoms continued to be paid after the law of 1991. During the 1990s there was actually more evidence of payments, perhaps because it was harder to hide the transfer of covert state funds from the media. In this regard, articles in the press speculated on the differences in status and value that were allegedly assigned to kidnap victims from the Italian North and South.

In the drafting process for the law of 1991, another well-known and important point came to the fore: investigators had been hindered by numerous problems in coordinating the enquiries and by elements of competitiveness between the different forces of order, as clearly illustrated in the case of the Casella kidnapping. The new legislation gave the Ministry of the Interior the option of establishing an inter-force unit answerable to the specific magistrate overseeing the kidnapping case, so that both the investigations and action would be coordinated. The special units, with their specific responsibilities, were made available. The initial stage of investigation was entrusted to the Reparti Investigazioni Scientifiche (Scientific Investigations Groups) within the Carabinieri, and covered attempts to negotiate with the kidnappers, including the use of professional agents and intermediaries rather than individuals known to those involved. The second stage related to decision-making and the potential use of armed action to liberate the victim. The special units for these operations were the NOCS within the police force and the GIS from the Carabinieri, but rivalry in the field was eliminated by the choice and implementation of one single action plan for liberation of the hostage (Carabellese and Zelano Reference Carabellese and Zelano2007).

Strategic alignment of the various bodies reduced the leeway for them to undertake covert activity. However, this alignment, which reduced uncertainties, was clearly not simply an organisational matter. At issue was the construction of not only a new organisational capability, but also new political priorities in a changing international framework. In the previous section, we argued that the Casella case had suggested two explanatory factors relating to the end of the kidnapping era: first, electoral pressure within a party system that was becoming more fluid than in the past; second, the way that the law enforcement system operated, shifting away from pursuit of the established practices for managing mafia kidnappings in order to adapt to the changing environment. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, this system found itself at a watershed in both organisational and, especially, strategic terms.

There is no doubt that the state was also improving its technical capabilities in regard to action on mafia kidnappings, in a variety of ways. The opportunities for dealing with a crime as physical as a kidnapping in a more direct way had considerably increased. New techniques that made it easier to identify the kidnappers during contact were being refined. Amongst other things, the United States was finally offering the use of its air force's geostationary satellites, which had previously not been available for this type of civilian purpose. In view of the large number of kidnappings, the investigative operation had accumulated information and reached a higher level of development. The growing professionalisation of the ’Ndrangheta gangs itself assisted the investigations. In contrast to the 1970s, operations in the 1980s became concentrated within a small number of families in the Locride area. In step with this, the families of professional kidnappers became more efficient, harvesting larger profits, but also more vulnerable as their numbers reduced.

Meanwhile, the impotence of politicians in stopping abductions reduced the legitimacy of the political class, which looked for support by altering the provisions for detention. A measure (Article 4b) was inserted into the prison regulations that banned the concession of privileges (granted by the Gozzini law) to some categories of offender, including anyone who had been involved in kidnapping for ransom unless they had actively collaborated with law enforcement agencies.

The course run by the kidnapping phenomenon was consistent with changes in the environment: initially there had been an abundance of facilitating factors and incentives to kidnap, but these had gradually been reduced and finally faded away. The appeal of the drugs trade certainly contributes to explaining the downward trajectory, but to a limited degree. If we want to offer a full explanation of the mafia's final abandonment of kidnapping, we need to recognise that the political factors and the action taken by the judiciary and law enforcement agencies made decisive contributions by impairing the conditions that had previously favoured the practice. In the cost-benefit analysis, it is striking that mafia kidnappers of the 1990s, unlike those of the 1970s, were at risk of armed attack and imprisonment without privileges or, if they collaborated, potential retaliation, in an environment in which they were in the spotlight. The four pre-emptive deaths at Luino made it clear that the tolerance previously shown by the state had disappeared.

In our concluding section, we suggest that an increasing number of deterrents were available as threats and resources of potential strength for a governing political class that in other ways had become very weak, having lost legitimacy and become fearful of the electoral consequences. The governing class addressed the final period of ’Ndrangheta kidnapping with the intention of bringing it to a close. However, the power struggle with the final cohort of kidnappers was more evenly balanced than the formidable range of new deterrents might lead us to suppose. This resulted in the reciprocal show of strength that was apparent in the kidnapping cases of longer duration.

Conclusions

The ‘why’ is sufficiently clear, but ‘how’ did the kidnapping era come to an end? The passing of the law of 1991 was a political marker, but in itself explains little; abductions did not cease in 1991, and their decline had started some while before. The average duration of kidnappings actually increased during the period when the law was in gestation and coming into force, perhaps precisely because of the political action under way. The law on freezing assets was not a watershed moment that modified criminal behaviour. It probably did not immediately change state behaviour (in the payment of intermediaries) either, nor could it stop a victim's family from trying every avenue in order to save their relative's life.

The law in itself thus seems to be a weak explanatory factor, while the political factors that we have described, taken as a whole, seem to have had a significant impact on kidnapping, but in ways that were complex and often indirect. We are suggesting that during the late 1980s and early 1990s, political factors (taken as a whole), which were linked to major changes in the international context and political system, exerted substantial pressure on kidnapping. These factors had at least two significant consequences: first, a change in electoral pressure, which encouraged – not least out of expediency – the organisation of a strong response to the crime; second, a period of adaptation and modification of the strategies and tactics employed by the national system for law enforcement, which at the start of the 1990s, as the Casella case shows, were still not apparent.

While a much-reduced number of mafia groups were still involved in the brutal practice of kidnapping, and not all of them were lining up to concentrate on more profitable and less risky activities (in particular the drugs trade), the political conditions were changing in a more marked fashion. The persistence of this crime became politically unacceptable, and the governing class was pushed into acting in a clearer and more visible way in order to defeat it. Moreover, new ways of doing this had developed. Kidnappers now had to contend with a situation in which important parts were played by media attention, the response of society, and the threat of more severe sentencing and dramatic armed action. At the same time, the political actors in government, especially the Christian Democrats, who wielded this ‘iron fist’, had never been so weak, and feared for their own political fate. This situation seems to have given rise to a final show of strength over ’Ndrangheta kidnapping and its violent practices, while the government, the governmental coalition, and the centre of the political system were also at stake.

The drafting of the law of 1991, which had symbolic as well as practical importance, can be understood as one element of a more complex political approach aimed at building up competitive advantages in order to win this struggle. The militarisation of the territory also had symbolic aims that were even more important than the practical ones. The media spotlight on the Locride area made an additional deterrent contribution, although in an era of private and emotion-driven television any media strategy was doomed to slip out of the hands of government control.

The manifestation of the state's strategy disrupted the fitful process of the ’Ndrangheta's withdrawal from its violent income-generating practice. The result was a stand-off, during which the duration of the last kidnappings lengthened without the practice actually stopping. At the beginning of the 1990s, a final encounter can be seen taking place between the opposing forces in the field. For the mafiosi, there were many logical reasons for abandoning this, but the situation continued to present opportunities that induced them to push their luck. The law enforcement system, on the other hand, was pursuing the end of kidnapping in a context in which long-established operational habits were under challenge, but still prevailed. In order to explain the way in which the kidnappings stopped, we need to take into account the undercover contacts between representatives of the Ministry of the Interior and the kidnapping gangs. These contacts do not seem to have ceased, even though state spokespeople were announcing their prohibition at the very same time. The stakes were too high for any useful avenues to be abandoned.

During this phase, the risks taken by the last kidnappers became much greater. It is more pertinent to ask why they continued to kidnap people, rather than why they stopped. Within the mafia organisation, conflict may have arisen between those who were unwilling to abandon the practice because they had not yet earned enough and had no other plans in development, and those who were vulnerable to its collateral risks without benefitting from its advantages. Some were still happy to try their luck, while others may have had more awareness of their victim's ‘ransom potential’ and political value, hoping to draw intermediaries and state informers into profitable exchanges. We believe that the bodies responsible for countering mafia activity strengthened their position with a formidable array of sanctions, but were still ready to accept the timescale and methods of negotiation. Kidnapping was thus brought to an end by the exercise of a dual approach. In this hypothesis, the Ministry of the Interior did not close down the financial channels and cease its undercover contacts prior to the ’Ndrangheta's abandonment of kidnapping, with the aim of persuading it to cease, but took these steps when this process was instead already under way, stimulating the gangs’ reorientation towards other activities. The price of the lives of the victims, or at least of the most well-known, including the electoral implications, was in fact too high for the governing class to be willing to bargain for their salvation using the old accustomed channels.

Translated by Stuart Oglethorpe

Acknowledgements

Creation of the new database was only possible thanks to the invaluable cooperation of staff in the Servizio Analisi Criminale at the Ministry of the Interior. We are particularly grateful to Vincenzo Calia, the investigating magistrate for the Casella kidnapping, whose collaboration allowed us to construct our case study; this was first presented at the Presidio di Libera, Pavia. We would also like to thank Francesco Battegazzorre, Alberto Cisterna, Roberto Di Palma, Aldo Varano and the journal's anonymous referees for their helpful advice and suggestions. This is the first article written jointly by its two co-authors, who became friends thanks to the ‘Rete29aprile per una Università libera, pubblica e aperta’ association of researchers.

Note on contributors

Cristina Barbieri is Assistant Professor (Ricercatrice) in the Department of Political and Social Sciences at the University of Pavia, where she teaches ‘Italian Political Systems’ and ‘Public Administration’. Her research interests are political power, the Italian government and, specifically, the role of the prime minister. Her publications include: Il capo del governo in Italia. Una ricerca empirica (Milan: Giuffrè, 2001); (with M. Vercesi) ‘The Cabinet: A Viable Definition and its Composition in View of a Comparative Analysis’, Government and Opposition 48 (4), October 2013; ‘Debolezza istituzionale e flessibilità del ruolo del capo del governo in Italia’, in Il presidente del Consiglio dei ministri dallo Stato liberale all'Unione europea, edited by L. Tedoldi (Milan: Biblion, 2019).

Vittorio Mete is Associate Professor in Political Sociology in the Department of Political and Social Sciences at the University of Florence, where he teaches ‘Sociology of Leadership’ and ‘Political Sociology’. His recent publications include: (with G. Corica) ‘The Case of the Suvignano Estate: A Story of Mafia, Anti-Mafia and Politics’, Partecipazione e Conflitto 13 (3) (2020); (with A. C. Freschi) ‘The Electoral Personalization of Italian Mayors. A Study of 25 Years of Direct Election’, Italian Political Science Review 50 (2) (2020); ‘The Trader Perspective: Researching Extortion in Palermo’, Modern Italy 23 (3) (2018).