Introduction: the press and Italian colonialism

This article builds upon a wealth of studies addressing the role of the Italian press in the promotion of Fascist colonialism. In recent years, scholars have conducted increasingly detailed and targeted analyses, and also used insights derived from other fields of study, ranging from the history of racism and the concept of ‘race’ to anthropological studies and gender studies, and historical-artistic analyses on the visual elements of colonial propaganda. Laura Malvano's analysis (Reference Malvano1988) on the importance of the figurative element in the multi-level communication strategy carried out by Mussolini's regime was particularly illuminating in this regard, as she coined the idea of a veritable ‘policy of the image’ implemented by Fascism, both in the sphere of mass culture and in that of so-called ‘high’ culture.

Methodologically, this article is indebted to recent investigations that combine two or more of these interests, such as those of Michele Nani (Reference Nani2006), who analyses several Italian newspapers from the late nineteenth century, highlighting the stereotypes which then prevailed about Africans, southern Italians and Jews; those of Francesco Cassata (Reference Cassata2008), who studies La Difesa della Razza, the well-known racist magazine founded in 1938; and those of Sara Kapelj (Reference Kapelj2010–11), who examines L'Italia d'Oltremare, a fortnightly magazine published in Rome in the final phase of Fascist colonialism, a period marked by the proclamation of the empire and the consequent intensification of Italian racial policy. An overview of the theme of expansionist propaganda through magazines, and in particular those with a specific colonial vocation, is offered by Stefania Frezzotti (Reference Frezzotti and Margozzi2005), who also briefly analyses the graphic design of a few magazines and the presence of articles on so-called ‘colonial’ Italian art, a topic that in recent years has begun to be explored in detail (Jarrassé Reference Jarrassé2016; Belmonte Reference Belmonte2016, Reference Belmonte2021; Tomasella Reference Tomasella2017, Reference Tomasella2020, Reference Tomasella2021; Manfren Reference Manfren2019a, Reference Manfren and Tomasella2020). Valeria Deplano (Reference Deplano2012, Reference Deplano2018), for her part, has devoted several studies to the birth and evolution of the colonial press, with particular regard to that of the Fascist era, examining the ‘colonial consensus factory’ and the role of the different magazines in relation to the main phases of national policy overseas.

With regard to the role of the illustrated press and propaganda in the invasion and consolidation of Italian colonial domains, it is from the 1980s onwards that scholars have started paying attention to their iconic (rather than solely textual) elements – especially in the context of the Italo-Ethiopian War, during which the regime's propaganda machine used all the means at its disposal, the press first and foremost, to mobilise Italians in favour of this African expedition (Mignemi Reference Mignemi and Mignemi1984; Caccia and Mingardo Reference Caccia and Mingardo1998; Righettoni Reference Righettoni2018).

Concerning the specific case of the magazine here under examination, Libia, it should be noted that although it has been investigated by various scholars, the analysis of its visual and artistic components has been limited or partial (Massaretti Reference Massaretti1992; Scardino Reference Scardino, Gresleri, Massaretti and Zagnoni1993; Munzi Reference Munzi2001, 106; Reference Munzi, Galaty and Watkinson2004, 89–90; Berhe Reference Berhe2017). The present study will therefore provide further information about the magazine under consideration and its visual apparatus, shedding light on the links between the magazine's contents and the political and cultural propaganda implemented for tourism purposes by Italo Balbo, governor of Libya between 1934 and 1940. As I will show, Libia turns out to be – already in its covers – a fictional image of the ‘Fourth Shore’ (that is, the name given by Benito Mussolini to the Mediterranean shore of Italian Libya) carefully calibrated in order to show visitors all the possible attractions of the region. Libia in fact highlights the particular stratification of cultures – the ancient and classical, the Arab and the Italian – present in the colony, trying, at least in appearance, to mediate the obvious tension between the preservation of tradition and impulses towards modernity, opposite poles that Fascism tried to make coexist in a difficult and complex harmony.

Italo Balbo and the development of the idea of the ‘Fourth Shore’

In the summer of 1933, Italo Balbo completed the Orbetello–Chicago transatlantic flight, reaching the peak of his glory and being celebrated both in Italy and overseas as a modern Columbus (Segrè Reference Segrè1988, 298). Not many months had passed after his aviation feat when the air marshal received a letter from Mussolini, dated 31 October 1933, informing him of his appointment as sole governor of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. The new position, at first not at all welcomed by Balbo, took him to Tripoli the following January; throughout 1934, he seemed to be ‘restless’ – as Emilio De Bono testifies in his diary – continuing to move repeatedly between the colony and Italy (Rochat Reference Rochat2003, 253). In December of that year, after several discussions with the Duce, Balbo finally obtained the fusion in a single colony, Libya, of the two administrative entities of which he had been put in charge (Segrè Reference Segrè1988, 355); from this moment he had greater freedom of action and could begin planning the modernisation of the so-called ‘Fourth Shore’ starting, first of all, with the improvement of the air and telephone communications network (Segrè Reference Segrè1988, 356–357). Balbo's most famous project, in terms of grandeur, material evidence and speed of construction, was the Litoranea Libica, a coastal road 1,822 kilometres long – in reality, only 799 were built ex novo – which ran from the Tunisian frontier to the Egyptian border (Segrè Reference Segrè1988, 356–361). Completed in little more than a year between 1936 and 1937, the Litoranea imposed itself as a tangible example of the ‘civilisation’ brought to the colony by Fascist Italy, which presented itself as the direct heir of Imperial Rome, as underlined in the article describing the enterprise published in the first issue of Libia and written by Balbo himself (Reference Balbo1937).

Improvements in the field of communications were therefore the first step, in Balbo's eyes, in demonstrating that Libya was now a safe territory which was readily accessible and worthy of being considered the ‘Fourth Shore’ of Italy. The governor's commitment aimed at a decisive relaunch of the colony's image: Libya should no longer appear as a land of clashes and repression of ‘savage’ populations, but as a destination ready to welcome both tourists in search of exotic and carefree stays and Italian farmers ready to populate its lands. To this purpose, Balbo's role as ‘builder’, namely as promoter of Libyan infrastructures and buildings, proved fundamental: already in February 1934 he appointed a commission responsible for the architectural development of Tripoli and its surroundings, thus showing a renewed aesthetic and urbanistic engagement on the part of the government (Segrè Reference Segrè1988, 369–370; for more on Tripoli during the Italian presence in Libya see Fuller Reference Fuller2007, 151–170).

In May 1935, Balbo also created the Ente Turistico ed Alberghiero della Libia or ETAL (The Tourism and Hotel Authority of Libya), an agency with the task of supervising and promoting all tourist activities. ETAL was also in charge of the construction and management of a chain of accommodation facilities for stays in the colony, such as the luxurious Hotel Casino Uaddan and the more modest Mehari, both built in Tripoli as part of a project of the Roman architect Florestano Di Fausto in collaboration with his colleague Giuseppe Gatti Casazza, one of the many friends from Ferrara whom Balbo, as we will see, called to Libya during the years of his governorship (Segrè Reference Segrè1988, 366; Scardino Reference Scardino, Castelli and Laurenzi2000, 241; McLaren Reference McLaren2006, 192–204).

Another building sector that received a strong impulse from Balbo was that connected to the construction of agricultural villages, which were key to implementing his agrarian policy projects and, from 1938, the plans for intensive demographic colonisation, which required Libya to be ready to welcome twenty thousand Italian settlers every year for five years (Rochat Reference Rochat2003, 266–275; Cresti Reference Cresti1996, 50–56). At an increasing speed from 1934 onwards, numerous villages, several of which were built by the architects Di Fausto, Giovanni Pellegrini and Umberto Di Segni, sprang up in various parts of the colony, mainly – but not exclusively – in Tripoli, Benghazi, Derna and Misurata (Gresleri Reference Gresleri, Gresleri, Massaretti and Zagnoni1993, 309–310; Stigliano Reference Stigliano2009, 105–113).

Many of these activities, as well as the attention given by the governor to the artistic and cultural elements of the region, emerge – as we shall see – from the pages of Libia, in both textual and visual form.

Archaeology, museums, handicraft and art in Balbian Libya

Another aspect in which governor Balbo invested considerable efforts was the development of the archaeological sites of Leptis Magna, Sabratha, Tripoli and Cyrene: the Libyan excavations, which had started during the Italian occupation in 1911, proceeded without interruption. Additionally, under Balbo's governance, excavations in Ptolemais began, and the restoration and consolidation of the Arch of Marcus Aurelius in Tripoli, as well as that of the ancient theatre of Sabratha, were carried out (Annuario generale della Libia 1939, 35–36; Segrè Reference Segrè1988, 366–367). The governor's attention to the rediscovery of ancient remains was, on the one hand, in line with the Fascist myth of romanità used to justify Italian expansionism in the Mediterranean (Munzi Reference Munzi2001, Reference Munzi, Dridi and Mezzolani Andreose2016; Balice Reference Balice2010; Troilo Reference Troilo2021). On the other, it was part of the strategy that aimed to make the Libyan colony an appealing tourist destination both for a mass audience, attracted by its so-called ‘oriental’ charm and its beaches, as well as for a more affluent and cultured elite interested not only in the many other attractions well-orchestrated by Balbo – such as trade fairs, sports and folk events – but also in the cultural possibilities on offer.

With regard to Libya's artistic and cultural heritage, Balbo's work in the colony also involved museums and the promotion of local handicrafts. One of his first decisions, as soon as he arrived in Libya, was to relocate the government offices, set up elsewhere in 1929 by his predecessor Pietro Badoglio, in Tripoli's Red Castle, an ancient symbol of power in the region and since 1930 the location of the new Archaeological Museum. Balbo did not move the museum to another building but promoted a series of modifications and restorations, entrusted to the aforementioned Gatti Casazza, assisted in the arrangement of the works of ancient art by Giacomo Guidi, Superintendent of Monuments and Excavations of Tripolitania from 1928. These operations also involved part of the complex of the Bastion of San Giorgio: here, where the museum of antiquities was located, the new government offices were set up, allowing many of the artefacts already present in the museum to remain on display and the public to visit these rooms free of charge on Sundays (Corò Reference Corò1934; Del Boca Reference Del Boca1988, 236; Falcucci Reference Falcucci2020, 424). Balbo's choice clearly reveals a ‘manipulative and partisan use of the archaeological heritage’ (Falcucci Reference Falcucci2020, 424), aimed at making the perception of the Italian presence in Libya as a legitimate and beneficial return to those territories that, in the past, had been part of the Roman Empire. Balbo also encouraged the creation of the Museum of Natural History of Tripoli. Set up in the former headquarters of the Banco di Roma and inaugurated in March 1937, it was conceived by the governor with the aim of offering tourists easy access to the geology, zoology, botany and ethnography exhibits collected in Libyan territory (Falcucci Reference Falcucci2017, 88–89).

The idea of developing the Libyan colony's potential attractions and tourism, together with a certain inclination for the arts, also drove Balbo to devote himself to the indigenous craft sector, which was further organised and strengthened during the years of his governorship. Alongside the School of Vocational Training in Benghazi and the better-known School of Arts and Crafts in Tripoli (which, under Balbo, was enlarged to include a ceramics department directed by the Sardinian Melchiorre Melis) further educational activities were devised. They aimed at promoting the artistic renewal of local craftsmanship by encouraging production that, although based on the indigenous tradition, was inspired by new trends promoted by Italian designers or artists. The context in which the results of this union were tested were the new artisan quarters set up by the governor throughout Libya, starting with the artisan quarter at the Arch of Marcus Aurelius in Tripoli, inaugurated in 1937, and continuing with those in Benghazi and Derna.

The coordination of the various activities was entrusted to the Fascist Institute for Crafts in Libya, set up on Balbo's decision in 1936 (G[ardenghi] Reference G[ardenghi]1937; Quadrotta Reference Quadrotta1937; Istituto Fascista per l'Artigianato della Libia 1938, 1482–1483; Pistolese Reference Pistolese1939). It should be noted that since the early 1920s – namely from the so-called ‘rebirth’ of Tripolitania during the governorship of Giuseppe Volpi, who was the first to pave the way for the development of tourism in Libya (Niccoli Reference Niccoli and Volpi1926, 511–512) and to establish a Government Office for Indigenous Applied Arts in the colony in 1924 (Rossi Reference Rossi and Volpi1926, 517–519) – Libyan production played a prominent role in the panorama of handicrafts and applied arts in the Italian colonies, although it was never treated as actual art and, therefore, always remained at the status of an exotic and picturesque curiosity. This was due to the stereotyped view of Libya at that time, presented by Italian writers and critics as a land that had remained underdeveloped and ‘primitive’ due to Arab domination and, for this very reason, in need of the Italian presence to progress (Manfren Reference Manfren2019b, 223). However, this progress had to be limited and, more than anything else, grafted onto the local tradition, in order to keep alive the folklore that tourists were looking for and would be disappointed not to find (Canella Reference Canella1938; A. A. 1940). Libyan handicrafts, therefore, were enhanced by Balbo for tourism promotion: bought in the colony, these objects became a souvenir with a presumed African ‘authenticity’ certified by the revival of traditional models. Exported and sold at numerous trade fairs, they became tangible and appealing emblems of the exotic attractions that Italian Libya could offer to those who visited it.

As several scholars have noted (Guerri Reference Guerri1984, 302; Del Boca Reference Del Boca1988, 233–246; Scardino Reference Scardino, Gresleri, Massaretti and Zagnoni1993, Reference Scardino, Castelli and Laurenzi2000; Rochat Reference Rochat2003, 254–255, 296), Balbo reacted to this sort of Libyan exile to which Mussolini had destined him by displaying a marked flair for public relations, organising spectacular parties to attract and welcome politicians, intellectuals and journalists as witnesses of the colony's progress thanks to his work. However, what really seemed to sustain him during his stay overseas was the creation of a small court in Tripoli, made up of friends and loyal supporters, many of whom came from Ferrara. These included the journalist and university lecturer Nello Quilici, former editor of the Corriere Padano founded by Balbo in 1925; the squadrist Claudio Brunelli, a long-time friend appointed by the governor as director of ETAL; and Pio Gardenghi, a journalist who had also been Balbo's secretary.

The governor also surrounded himself in Libya with numerous figures linked to the arts; the reason for these contacts was, in several cases, the realisation of works and decorations in Tripoli and in the villages that were being built in the colony. Among many, the first that should be mentioned is certainly Achille Funi, the Ferrarese painter called in 1936 to fresco the governor's palace and the church of Saint Francis in Tripoli, as well as supervising the decoration of other Libyan buildings and churches. Other members of the Balbian court include Emma (Mimì) Buzzacchi Quilici, a female painter and wife of Nello, Galileo Cattabriga and Aldo Chiappelli, the former a painter and the latter an engraver, both from Ferrara, and Nives Comas Casati, a versatile artist and niece of the famous illustrator Marcello Dudovich. Furthermore, Felicita Frai Lustig and Virginio (Gino) Ghiringhelli, one from Prague and the other from Milan, both collaborators of Funi in other fresco works, also arrived in Libya, in addition to Mino Maccari, illustrator and director of Il Selvaggio, Mauro Reggiani, an Abstractionist artist from Modena, Carlo Socrate, an artist based in Rome who was once Mimì Buzzacchi's teacher, and Tato (Guglielmo Sansoni), an eclectic artist from Bologna who was close to Futurism and had already created some murals in Quilici's house and in the Ferrara offices of the Corriere Padano. As I will show below, some of these artists of Balbo's entourage, together with others already present in the colony, went on to create several covers for Libia.

Libia and its covers

The date 12 March 1937 was an important one for Balbian Libya: the Duce arrived for the inauguration of the Litoranea, making a journey that took him to Tripoli in a few days, rapidly passing through other places including Cyrene, Benghazi, Sirte and Misurata (Munzi Reference Munzi2001, 82–83). It was precisely to celebrate Mussolini and the Litoranea that the publication of Libia began in the same month, and continued until 1942, albeit with changes due partly to Balbo's death in June 1940 and then to rapid upheavals in the international political situation.

The magazine was published by the ETAL, with management and administration in Piazza Castello in Tripoli, and printed by the Stabilimento Poligrafico Plinio Maggi, also in the Libyan capital. The periodical had a medium-large format (37 x 27 centimetres) with illustrated covers – sometimes photographic – printed in four-colour process; it presented inside tourist illustrated advertisements, articles accompanied by photographs (but also by drawings) and a final part dedicated to the Notiziario Corporativo della Libia (Libyan Corporate Newsletter). Libia was published monthly and could be purchased either as a single issue at five lire or by subscription, respectively at 50 lire for Italy and the colonies and 90 lire for abroad. Libia, as a publication of ETAL, was in fact a Balbian product, as the statute of the institution guaranteed the governor control over the administrative board, reserving to him the prerogative of appointing its members (Berhe Reference Berhe2017) and thus, indirectly, of supervising the magazine.

The first issue indicated an editorial board composed of Carlo Enrico Rava, a well-known rationalist architect, Balbo's loyal followers Gardenghi – who was also the director of Libia – and Brunelli. In addition, the editorial committee also included the director of daily newspaper L'Avvenire di Tripoli Ugo Marchetti and writer Francesco Corò, a soldier and author of numerous texts on Libyan affairs, former editor of Tripolitania – the monthly illustrated magazine of the Tripolitan Fascist Federation– and, from 1940 on, director of Libia. As early as 1937, as can be seen by leafing through the July issue, Mario Scaparro and Aroldo Canella joined the committee. The former was a public official and author of several writings on colonial subjects including one on Tripoli's handicrafts; the latter, delegated with the role of editor-in-chief, had been already active in the Rivista di Ferrara, the monthly illustrated magazine directed by Nello Quilici.

As I will show in what follows, Libia presented itself as a periodical aimed at tourist propaganda, in line with Balbo's aspirations for the future development of the region. The magazine used colonial imagery closely bound to the peculiar context of the Mediterranean colony characterised, unlike other territories occupied by Italy, by a strong Roman heritage that the magazine cleverly proposed in alternation with its indigenous component, which was endowed with the orientalist flavour that many tourists were still looking for. The experience of the ‘Other’ culture – declined in all its forms and sometimes reinvented – was nevertheless proposed within a safe and modern context, a new Libya equipped with every comfort, the result of a careful programme aimed at encouraging colonial tourism (McLaren Reference McLaren, Maciocco and Serreli2009).

Readers of Libia were in fact offered texts on the history and art of the region's past – not exclusively on the Roman period – alternating with articles on improvements and building developments promoted by the Fascist regime. Fascist Dopolavoro (After-Work) cruises were described and encouraged, and advice was given on how to travel and where to go, with routes that included visits to archaeological sites, oases and colonial villages. Shots of tourist life on Libyan beaches were published, as well as texts describing inland landscapes. Chronicles of the Tripoli Grand Prix car races, celebrating the myth of speed, alternated with texts on the agricultural work of indigenous Libyans and Italian colonists alike. There was no lack of articles about Libyan handicrafts, entertainment texts and colonial literature, a column on the local theatre, but also chronicles of events, meetings and activities associated with politics and propaganda. Libia, therefore, offered a (highly partial) overview of life on the ‘Fourth Shore’, in order to highlight the apparently successful union between tradition and modernity in the colony, in the typical manner of Fascist propaganda.

Some scholars point out that Libia had an approach singularly close to the one of the aforementioned Rivista di Ferrara (Scardino Reference Scardino, Gresleri, Massaretti and Zagnoni1993, 292) – due to the fact that several members of the latter appear in the editorial staff and among the contributors of the colonial periodical. A substantial difference between the two publications, however, should be noted, starting from the object of investigation of the present work, namely the covers. Those of the Ferrarese magazine – published between 1933 and 1935 and marked by Futurist and Avant-garde echoes – were mainly signed by Mimì Buzzacchi Quilici (Picello Reference Picello2012, 136–139), replaced on three occasions by Tato, Donato Santini and Nives Comas Casati; the covers of Libia, on the other hand, presented a wide range of authors with very different styles – ranging from Futurist modes to figurative approaches, passing through rapid evocations of classicism with a Novecentista taste – and, sometimes, the use of full-page photographs. It seems as though the choice to publish covers by various artists was a way to communicate the wealth, prestige and openness of Libia and, therefore, of the colony it represented.

In this aspect, Libia also differed from other colonial periodicals, such as Cirenaica Illustrata, published from 1932 to 1935, and Etiopia: rassegna illustrata dell'Impero, published between 1937 and 1943. In the former, the covers – which featured themes and subjects similar to those of Libia, but perhaps with an even greater presence of stereotypical indigenous portraits and scenes – were mostly illustrated with drawings by Rinaldo Bonati, and occasionally with woodcuts by Salvatore Piromalli. In the second, instead, Aldo Pagliacci's images dominated, sometimes replaced in the 1940s by those of Armando Bonanni; in this case, covers dedicated to Ethiopian fauna – depicting, for example, a lion, giraffes, a leopard, a baboon – link Ethiopia to the idea of a land still wild and adventurous. The Balbian magazine was also quite different from the aforementioned Tripolitania, published from 1931 to 1934, which mostly featured photographic covers.

Libia, however, looked towards models of more illustrious Italian periodicals of national scope such as, for example, La Rivista Illustrata del Popolo d'Italia, the well-known magazine founded by Arnaldo Mussolini that from 1923 published covers signed by numerous well-known artistic figures (Manfren Reference Manfren2016). It should be noted that some of the illustrators of Mussolini's periodical were the same ones who later collaborated on the Balbian magazine: this was the case for Funi, Frai, Tato and Mario Vellani Marchi (Manfren Reference Manfren2016, 150). Libia covers were also signed by Amerigo Bartoli, BOT (Osvaldo Barbieri), Ambrogio Casati, Gina Chiozza Lorenzi, Maccari, Sistina Magenta, Milo Corso Malverna, Melchiorre Melis, Buzzacchi Quilici and Bruno Santi.

Classical antiquity, local tradition and the developments brought to the colony by the Fascist regime were the macro-themes around which the subjects of most of Libia’s covers revolved. These topics were respectively evoked by the depiction of vestiges of the past, indigenous types and activities, and enterprises and famous Italian figures in Balbian Libya. For the summer months, by contrast, illustrations were proposed with more cheerful and holiday themes – for example, a view of the beach in Tripoli crowded with tourists or one with a local plant in bloom – in line with the magazine's tourist propaganda aims. The various souls of Fascism (imperial, rural, modern) thus found expression thanks to this evocative communication through images; moreover, in this way, Libia's covers often functioned as a visual preview of the internal contents. This kind of communication proposed, in addition to themes and figures that were immediately comprehensible, high-culture visual quotations. The latter were not always easy to decipher unless they were then revealed, at least partially, by the explanatory note on the magazine's inside front cover; however, this sophisticated and somewhat mysterious aura was certainly a characteristic that made these covers compelling and able to attract the curiosity of the readers.

As mentioned, a prominent place in the covers was reserved for the artistic evidence of the Libyan past, in particular – but not exclusively – the Roman. In fact, archaeological vestiges were often used in other journals too, such as in La Rivista Illustrata del Popolo d'Italia (Manfren Reference Manfren2016, 129–135), as indisputable evidence of the ancient Roman presence in the region, in order to motivate and consolidate its status as a colony within the Fascist empire. Such covers saw the artists drawing inspiration from architectural remains, sculptures, frescoes, mosaics and coins brought to light by Italian excavations, restored and, if possible, presented to the public in the aforementioned Tripoli Castle Museum. For example, the cover that Tato designed for the March 1937 issue, the first of the magazine celebrating the Libyan Litoranea, evoked in a dynamic photomontage, with a stylised Fascist emblem in the background, the great works of Imperial and Fascist Rome in the colony: the remains of the Roman theatre of Sabratha appeared together with the new roads laid out by Italy and the Arae Philaenorum, the arch built by Di Fausto as an imposing sign of the Fascist presence in the Libyan desert. Felicita Frai, for the covers of July 1937 and June 1938, looked at two mosaic works from the Roman villa of Dar Buc Amméra in Zliten, which had been kept in Tripoli since 1914 and then exhibited in the Archaeological Museum at the Castle (Aurigemma Reference Aurigemma1926; Falcucci Reference Falcucci2020, 422). In the first, the artist evoked the personifications of the ‘Four Seasons’ of the homonymous mosaic (Aurigemma Reference Aurigemma1926, 103), placing them on a Pompeian red background and superimposing, on the whole, the figure of a headless marble statue, probably also from the museum's collections. For the second illustration, Frai reworked a scene from the ‘Mosaic with amphitheatre scenes’, where in the bands with gladiator duels an orchestra appeared (Aurigemma Reference Aurigemma1926, 139, 150–151). For the cover of the October–November 1937 issue, Funi was inspired by the photographic documentation of an article (Meliu Reference Meliu1937), which showed examples of coins from the third century BCE displaying on one side the ‘silfio’, an ancient plant of the old Libyan region, and on the other a profile of the bearded head of Zeus Ammon. The same artist, for the January 1938 issue, portrayed the image of a ‘faceless deity’, one of the singular Greek statues of female funerary deities found in Cyrene that the painter had admired during a tour together with Pio Gardenghi (Reference Gardenghi1938, 17). Immersed in a golden background, marked by blue-white clouds, appeared the figure of Dionysus riding a panther: this was the image for the cover of April 1938 proposed once again by Funi, who had been inspired by the central portion of a Roman fresco, also found in the villa of Dar Buc Amméra and visible in the antiquarian collection of the Museum of Tripoli (Aurigemma Reference Aurigemma1962, 41–44).

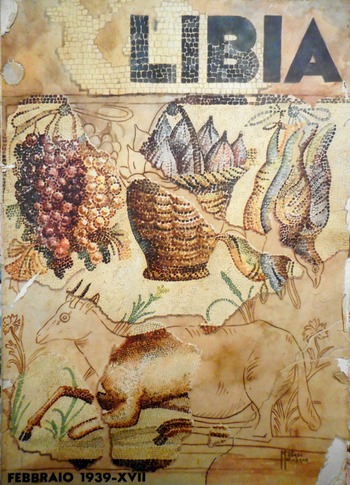

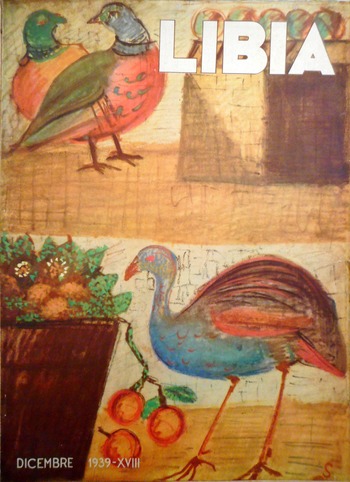

For the February 1939 cover (Fig. 1), colonial artist Milo Corso Malverna, a painter and sculptor active in Somalia in the late 1920s and then in Libya from the 1930s onwards (Manfren Reference Manfren2019a, 53–54; Reference Manfren and Tomasella2020, 68–70), created a pictorial reproduction of a mosaic found in a Roman building near Forte della Vite, just outside Tripoli: at the top appeared two bunches of grapes, a basket of figs and three partridges, at the bottom a gazelle (Aurigemma Reference Aurigemma1960, 30–32). In contrast to his colleagues, the artist reproduced the image of the mosaic in an accurate manner, imitating the tesserae with very small dots of colour and, where they were not present, reproducing the design that suggested the missing parts. The Lombard painter Sistina Magenta, who arrived in Libya during the Balbian period (Carlini Reference Carlini1990, 94), created the cover of December 1939 (Fig. 2) by looking at a panel of the famous ‘Mosaic of Orpheus’, found on a Roman farm in Leptis Magna and, like the previous ones, later placed in the museum of Tripoli (Aurigemma Reference Aurigemma1960, 52–54). The painter and sculptor Ambrogio Casati, born in Voghera but in Libya between 1937 and 1942 for military reasons, also produced illustrations with subjects taken from antiquity: in his covers of August–September 1939, October 1940 and June–July 1941 he depicted, respectively, a grape harvest scene derived from a pilaster strip found in Leptis Magna, an image inspired by a Carthaginian coin with a horse and a palm tree as subjects (Bono Reference Bono1999, 286–287), and a sculptural effigy of Berenice I of Cyrenaica that had previously appeared in the magazine (Meliu Reference Meliu1938, 18). The anonymous cover of January 1939 stood out from the previous ones: inspired by rock art, it might have been prompted by an article by Paolo Graziosi (Reference Graziosi1939), in which the Florentine scholar illustrated his recent discoveries.

Figure 1. Milo Corso Malverna, cover for Libia, February 1939 issue; private collection, Rome

Figure 2. Sistina Magenta, cover for Libia, December 1939 issue; private collection, Rome

The covers which were intended to illustrate the indigenous element can be divided into those devoted to architecture, those depicting types and those focusing on handicraft production.

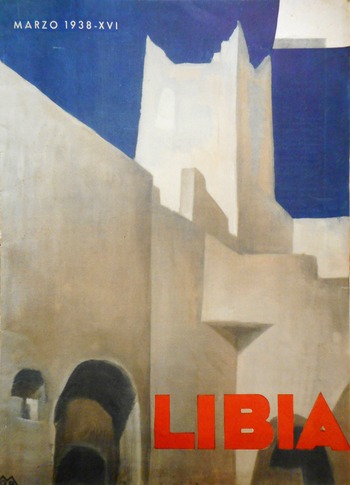

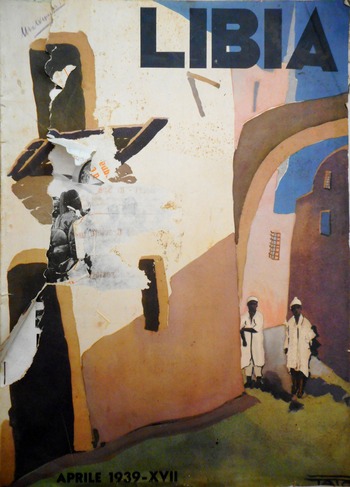

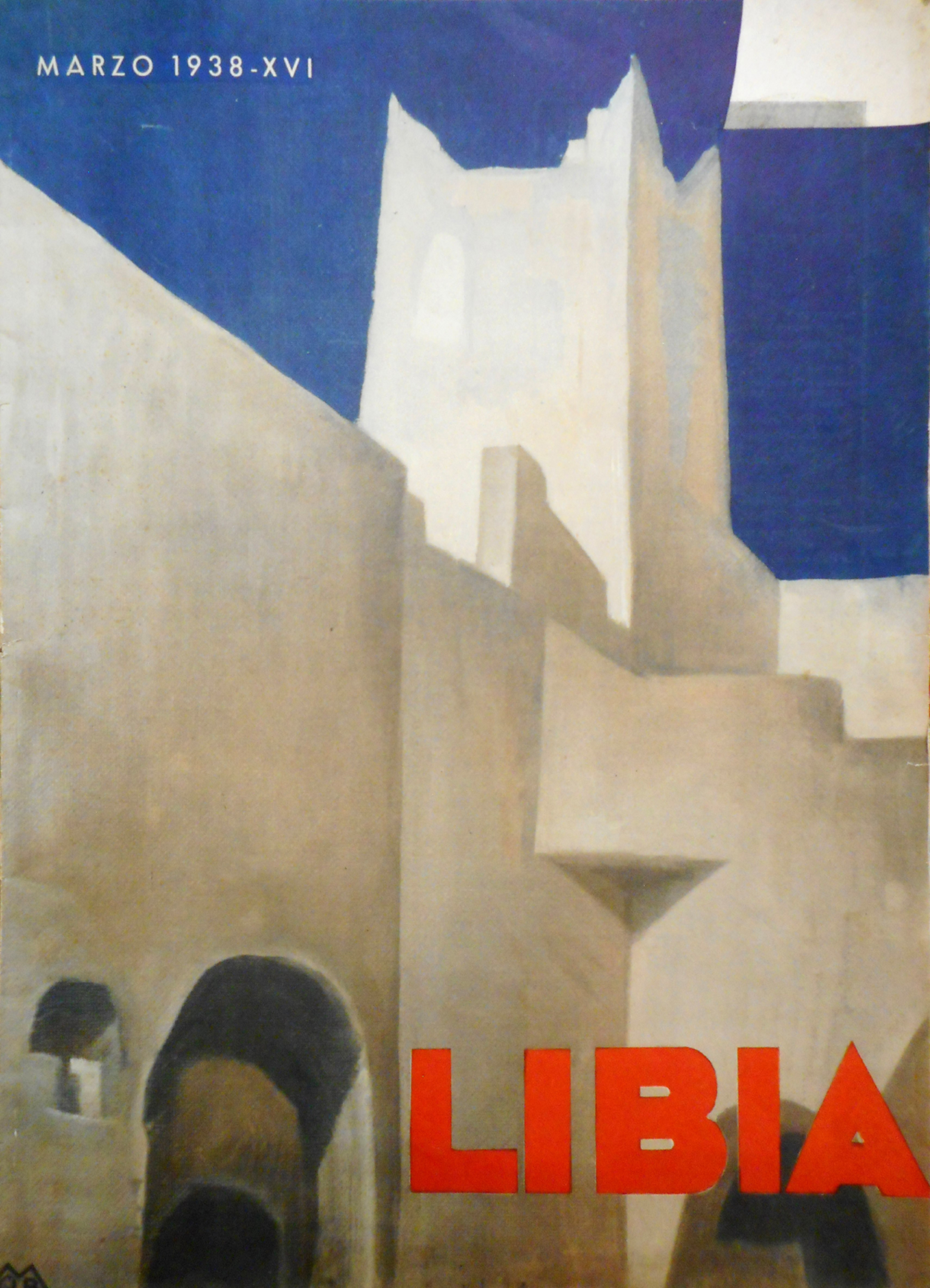

For the first group, we can mention the cover depicting white Libyan architecture with a minaret proposed for June 1937 by Santi, an artist from Bologna who had come to Libya to fresco the church of the village of Bianchi (Santi Reference Santi1939). In March 1938, the magazine reproduced an oil painting by Buzzacchi Quilici entitled Notturno a Gadames (Night-time in Ghadamès), which was exhibited that same year with other works on colonial subjects in the artist's solo exhibition in Ferrara (Fig. 3). A watercolour by Tato, depicting two native children in the streets of old Tripoli, was instead used for the April 1939 issue (Fig. 4).

Figure 3. Mimì Buzzacchi Quilici, cover for Libia, March 1938 issue; private collection, Rome

Figure 4. Tato (Guglielmo Sansoni), cover for Libia, April 1939 issue; private collection, Rome

With regard to local types, figures of children appeared as the main subjects in the December 1937 and February 1938 covers, one designed by Frai, the other reproducing a photograph; the former, in particular, had an obvious propaganda message, since it placed an imposing Italian tricolore behind the Bimbi arabi di Tripoli (Arab Children of Tripoli) – this is the caption given by the magazine. A farm labourer and a shepherd were the subjects of the September 1937 and May 1939 covers, created respectively by Bartoli, an artist who painted the frescoes for the churches of the village of Oliveti in Tripoli and the village of Garibaldi near Misurata (Carlini Reference Carlini1990, 85–87, 97, 172), and by Chiozza, a Ligurian female painter who in the same year exhibited her works, together with other artists such as Melis, Malverna and Casati, at the third Libyan Fine Arts Union Exhibition (Manfren Reference Manfren and Tomasella2017).

Bartoli's cover, entitled La raccolta dell'alfa (The halfah grass harvest) and promised a few months earlier by the author to Gardenghi (Carlini Reference Carlini1990, 82), was to evoke in colour what was announced with autarchic emphasis on the front page of the magazine, namely the excellent results of the harvest of this particular plant – also known as ‘sparto’ – which was used to produce cellulose. In this regard, it should be noted that this kind of image is very similar to those created for the so-called ‘Battle of Wheat’ launched earlier by Mussolini. The stereotypical image created by Chiozza and entitled Pozzi nel deserto (Wells in the desert) – depicting a Libyan shepherd in an expanse of sand watching his flocks drink – also alluded to the results of Balbo's activities in Libya; in fact, it referred to an article in which G[ardenghi] (Reference G[ardenghi]1939a) celebrated the resolution of water supply problems thanks to the construction of wells and cisterns promoted by Balbo's government.

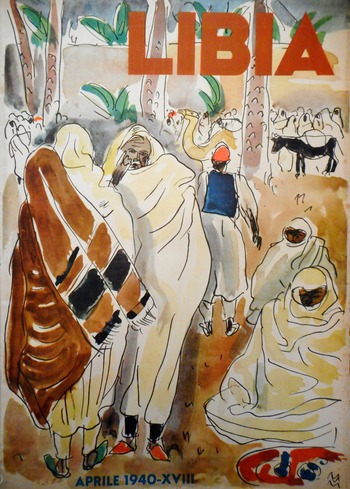

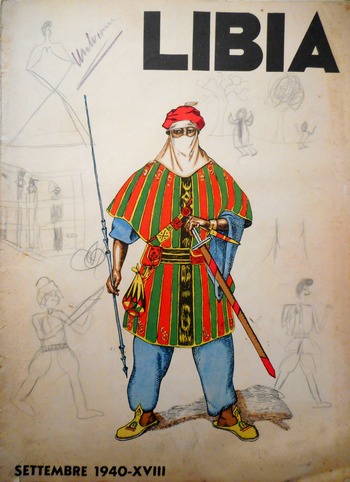

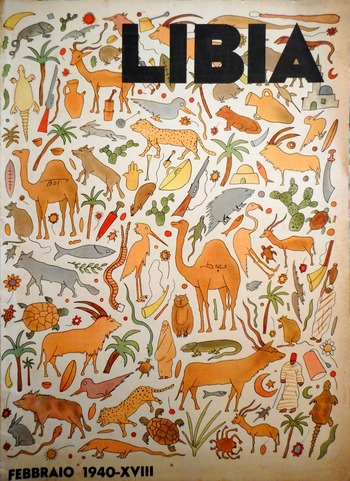

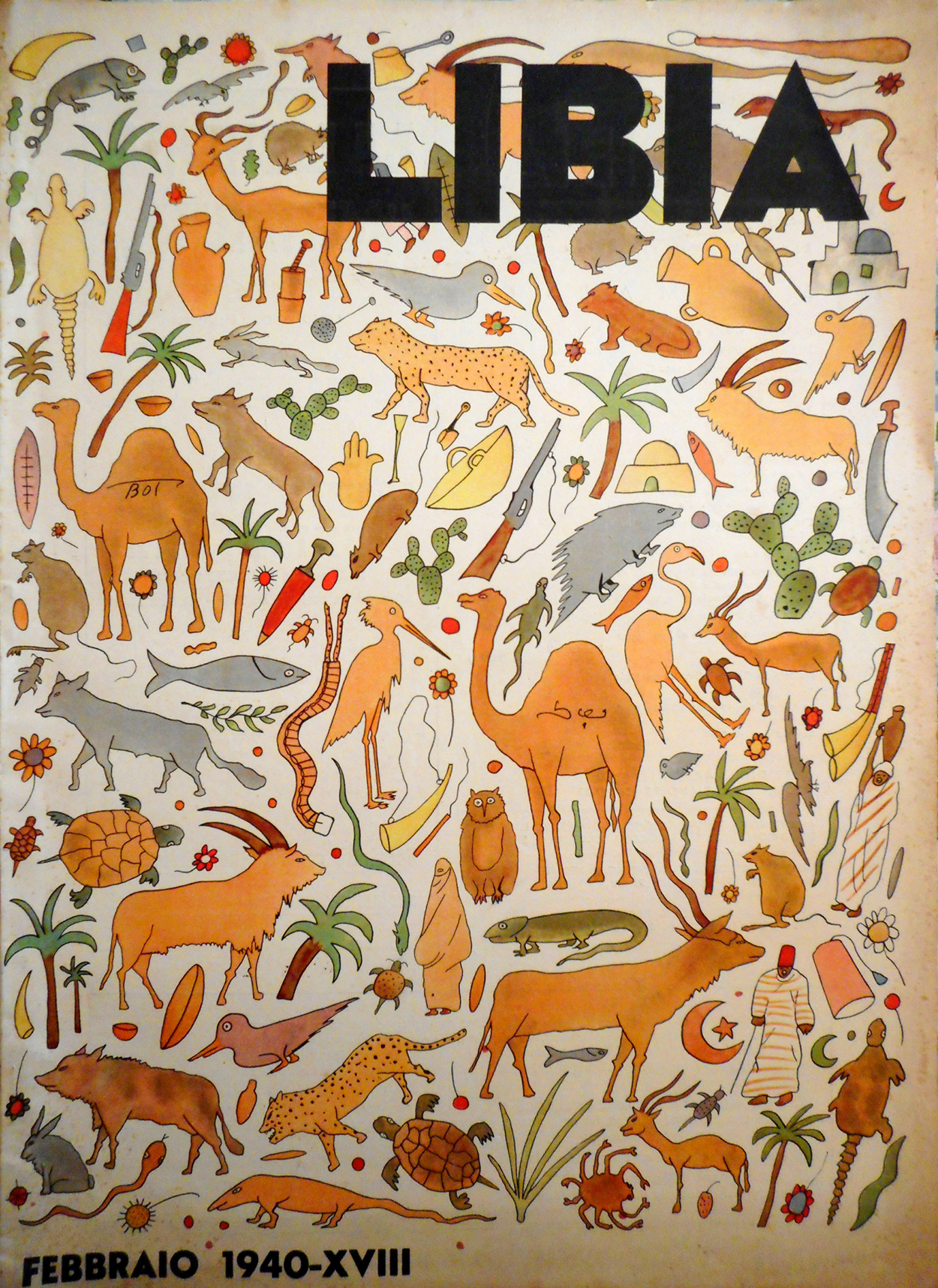

The April 1940 cover (Fig. 5) featured a sketch by Vellani Marchi, a Modenese artist who had travelled in Africa between 1934 and 1935 with journalist Orio Vergani and in Libya in 1939 with other artists such as Bernardino Palazzi and Enzo Morelli (Manfren Reference Manfren2019a, 179). In this case, there is no reference to modern Balbian Libya: on the contrary, the artist took inspiration from an iconography typical of nineteenth-century Orientalist art and reworked an Arab market scene in his rapid, lively style. In this way, the magazine provided readers with an exotic and static image of the colony, where mysterious cloaked figures, palm trees and camels could still be found. The same kind of suggestion emanated from the figure of an ancient Gadamesian warrior, dressed in brightly coloured oriental clothing, which Casati created for the September 1940 cover (Fig. 6). In February 1940, an original interpretation of the Libyan milieu was offered by BOT, a Futurist artist from Piacenza who, appreciated by Balbo, had been dividing his time between Italy and Libya since 1934 (Pontiggia Reference Pontiggia2015). In his Fauna libica (Libyan fauna), the artist presented a naïf vision of the colony, filling all the available space with endearing animal figures, which he placed alongside the most disparate objects, symbols and characters of the region (Fig. 7). Perhaps, for this intricate creation, BOT took inspiration from some ancient mosaics with plant and animal subjects such as those in the Justinian Basilica in Sabratha and the Roman baths in Uàdi ez-Zgàia (Aurigemma Reference Aurigemma1960, 27–29, 43–45).

Figure 5. Mario Vellani Marchi, cover for Libia, April 1940 issue; private collection, Rome

Figure 6. Ambrogio Casati, cover for Libia, September 1940 issue; private collection, Rome

Figure 7. BOT (Osvaldo Barbieri), cover for Libia, February 1940 issue; private collection, Rome

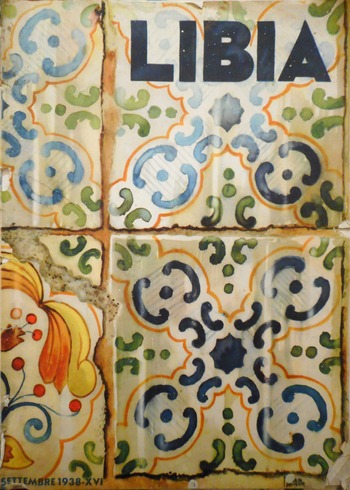

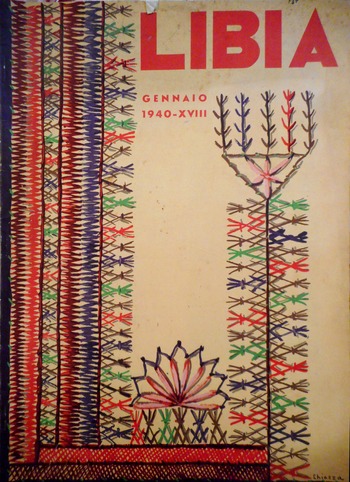

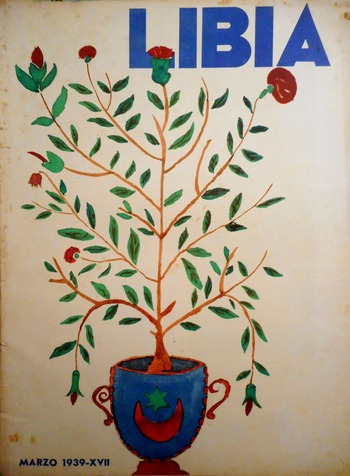

The attention given by Balbo to Libyan handicraft and its developments was also reflected, as I have already mentioned, in the covers of Libia. For instance, Corso Malverna for September 1938 faithfully reproduced in watercolour specimens of ancient Libyan ceramics (Fig. 8), an image that should be read in connection with Melis's article (Reference Melis1938) on local production and the progress achieved by his school in this field; interestingly, in the same year Melis had also prepared a sketch for a cover very similar to Malverna's (Cuccu Reference Cuccu2004, 90). Another example is the image for January 1940 created by Chiozza, which reproduced Libyan motifs for women's ornaments (Fig. 9), giving a preview of an article written and illustrated by the artist herself and focused on the art of embroidery. With regard to the March 1939 cover (Fig. 10) – which reproduced a watercolour entitled Primavera (Spring) – it is worth underscoring a discriminatory attitude towards indigenous authors: in this case, in fact, the artist is left anonymous, the magazine simply refers to him as an Arab boy from the Muslim School of Indigenous Arts and Crafts.

Figure 8. Milo Corso Malverna, cover for Libia, September 1938 issue; private collection, Rome

Figure 9. Gina Chiozza Lorenzi, cover for Libia, January 1940 issue; private collection, Rome

Figure 10. [Anonymous], cover for Libia, March 1939 issue; private collection, Rome

The regime, its personalities and the change it brought to the colony were themes that equally found space on the covers of Libia. For instance, the October–November 1938 issue celebrated the arrival of the first 20,000 settlers in Libya by presenting the various agricultural districts and the architects’ projects; one of these – the new village of Oberden designed by Di Fausto – appeared on the cover in a drawing by Casati. The October and November 1939 covers were once again focused on the demographic colonisation and its protagonists: the first one was illustrated by Funi and showed a settler intent on hoeing the land near typical small houses of the recently created agricultural districts; the second one was photographic, and portrayed, as the inside front cover indicated, the ‘serene strong face of a rural housewife who arrived in Libya with the second wave of colonists’.

The June 1939 issue, instead, aimed to glorify Libya's renewal in the artistic field: on this occasion, the cover reproduced an angel's head, taken from a fresco that Funi had painted in the aforementioned church of Saint Francis in Tripoli. In the same issue, a text by Gardenghi (Reference Gardenghi1939b) and one by Eugenio Giovannetti (Reference Giovannetti1939) on the same subject, dealing respectively with the work and the painter, were published. Just as Balbo's coming to Libya had been greeted by Cirenaica Illustrata in February 1934 by publishing a portrait of him by Bonati on the cover, Libia similarly celebrated the governor shortly after his death in the monographic issue of May–August 1940, where a profile of the Ferrarese politician painted by Funi was reproduced on the cover. Balbo's Libia had ended.

Conclusion

It is clear from this overview that Libia echoed Balbo's interests and policy on the ‘Fourth Shore’, where art was used as a powerful means of self-celebration and propaganda. The magazine's covers, lively and often slightly fanciful pictorial transpositions of what a tourist may have found in Libya, are fully in line with the iconic tradition and ‘politics of the image’ orchestrated by the Fascist regime. The attention and the prominent role given to different artistic treasures and cultural expressions present on the Libyan soil by the Ferrarese governor can also be found in both the iconic and textual parts of Libia, a periodical that proves to be the product of a calculated political and touristic propaganda strategy, scrupulously overseen by Balbo through his most trusted collaborators. Gone are the photographic images marked by the languid exoticism of the nineteenth century, as occurred in Tripolitania, as well as illustrations depicting, in most cases, indigenous types and scenes of life, as on the covers of Cirenaica Illustrata: the variety of visual approaches – marked by a multiplicity of authors and styles – and thematic proposals offered by Libia are, themselves, expressions of the modernising approach that Balbo aspired to bring to the Mediterranean colony.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Priscilla Manfren is a Research Fellow in Museology and Art and Restoration Criticism at the Department of Cultural Heritage, University of Padua. Her studies focus on the Fascist period and pay particular attention to issues related to colonialism and the exploitation of art for propaganda purposes. She tackles these subjects through the analysis of various types of sources and media. She has recently become interested in contemporary African and African Diaspora art.