Adivasi labour in (post-)colonial India

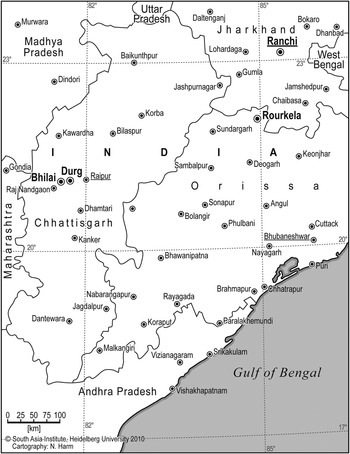

Rourkela is a town of 500,000 inhabitants in the hilly border region of the eastern Indian state Odisha and its neighbouring states Chhattisgarh (until 2000 part of Madhya Pradesh) and Jharkhand (until then part of Bihar) (see Figure 1). Rourkela became Odisha's industrial capital when the Government of India established the large Rourkela Steel Plant (RSP) here in the 1950s, which soon attracted many ancillary and downstream industries. These industries employed workers from local and nearby villages, from the coastal districts of Odisha that lie 300 km east and southeast of Rourkela and where the famous temple town of Puri and the state's capital Bhubaneswar are situated, as well as from other Indian neighbouring states, such as Bihar, West Bengal, and Andhra Pradesh, but also distant ones like Punjab and Kerala.

Figure 1. Rourkela in Odisha (until 2010 spelt Orissa) and eastern India. Source: Map originally produced by Nils Harms of the South Asia Institute for C. Strümpell, ‘Ethnicity, class and citizenship on a contested frontier: politics and the public sector steel plant in Rourkela, Orissa’, in The politics of citizenship, identity and the state in South Asia, (eds) H. Bhattacharyya, A. Kuge and L. König (New Delhi: Samskriti, 2012), pp. 169–84. Reproduced with permission.

As is the case for other ‘steel towns’ that the Government of India established elsewhere in central-eastern India then,Footnote 1 the industrial working class that emerged in Rourkela was highly heterogeneous in terms of ethnicity and caste. A remarkable feature of the steel workforce in Rourkela is the relatively large number of workers from communities that are officially categorized as ‘Scheduled Tribes’, such as—to name the largest ones—the Munda, Oraon, and Santal, which are also referred to as ‘tribal’, ‘indigenous’, or ‘Adivasi’ (literally ‘first settlers’).Footnote 2 The official category of ‘tribe’ goes back to policies the British colonial ethnographic state of the nineteenth century crafted to order Indian society on the basis of European evolutionist ideas of race and partly also on pre-existing upper-caste notions.Footnote 3 In the colonial epistemological scheme, the forested highlands of the Chota Nagpur region in central-eastern India, to which the Rourkela region belonged, formed ‘zones of anomaly’ that had to be administered in different ways than the river valleys and plains because its inhabitants were primitive and savage ‘aboriginals’ or ‘tribes’ and, as such, fundamentally different from caste society.Footnote 4 Their wildness expressed itself in raids they regularly unleashed on the settled peasants at the foot of the hills already in precolonial times and throughout the eighteenth century. This gave rise to the colonial notion of the ‘tribes’ as free, brave, and manly, in contrast to the ‘effeminate’ castes.Footnote 5 Nevertheless, the colonial state did not tolerate such incursions and regularly launched military campaigns to ‘pacify’ the unruly tribes, which eventually turned them into impoverished subalterns. However, in the colonial imagination, rapacious upper-caste Hindu landlords and moneylenders who had come along with the British expansion into Chota Nagpur were responsible for the impoverishment of the tribes as well as for their frequent rebellions against it. Hence, they identified certain groups and regions as Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Areas to protect their rights over forest, land, and water, a policy that persisted in the post-colonial period.Footnote 6

Ghosh emphasizes that the ‘othering’ of ‘tribes’ or ‘aboriginals’ of Chota Nagpur was centrally about labour.Footnote 7 The ‘tribes’ of Chota Nagpur were said not to shy away from any kind of work, however menial, to know no food taboos, and to eat little.Footnote 8 Therefore they were ideally suited to solve the ‘labour problem’ in the colonies, that is, the scarcity of available labour power in relation to land resources, which was aggravated by slave emancipation in the 1820s. They were highly coveted, especially by colonial planters, first on island colonies across the world, and from the mid-nineteenth century on the tea plantations of Assam.Footnote 9 The pacification wars aimed at producing an uprooted and hence docile ‘coolie race’ for the colonial plantation economy, and they were tellingly also referred to as ‘coolie campaigns’.Footnote 10 However, Ghosh and others emphasize that tribal labour was only fetishized as migrant labour. The ‘tribes’ living around the plantations in Assam were dismissed as ‘lazy natives’, and also the tribes of Chota Nagpur, the prototypical ‘coolies’, were considered indolent, constantly drunk, with the bad habit of coming to work as they liked, and thus unemployable by the owners of coal mines in Chota Nagpur itself.Footnote 11 The seemingly contradictory assessments of ‘tribal’ labour power is an expression, Ghosh argues, of the fact that in the colonies primitive accumulation remained incomplete, that producers retained access to some (however meagre) means of production, and that colonial capitalists could control labour only if producers were spatially separated from their home turf.Footnote 12

The stereotyping of Adivasis in Rourkela resembles both the ‘coolie race’ and the ‘lazy native’ stereotypes of colonial times, but these contradictory assessments reflect changes in the political economy of public sector industries rather than differential access to means of production. Adivasis belonged to different ‘Scheduled Tribes’, they were Hindu or Christians, they were locals from Rourkela, or they were migrants from nearby districts. Regardless of these differences, Adivasis were said to be jangli (‘savage’), to have brawn, but to lack education and to drink heavily. Therefore, my upper-caste interlocutors routinely emphasized, Adivasi RSP workers could cope better than others with the especially hazardous working conditions in RSP's so-called ‘hot shops’ (the coke ovens, blast furnaces, etc.). On other occasions, the same or other interlocutors from the same caste background often further claimed that Adivasis are, in fact, not well suited for regular jobs in RSP. As a public-sector undertaking, RSP provides regularly employed ‘company workers’ with almost watertight job security and munificent salaries compared to the ancillary and downstream industries, especially those in the private sector. Because of their limited wants, the relatively privileged public-sector employment allegedly does not do Adivasis any good, but only makes them drink more and work less. Instead, Adivasis make excellent ‘contract workers’. These are employed through contractors, not directly by the company where they work, which means that they are paid little and by the day, and they can be hired and fired at will. As with other public and private sector industries all over India, RSP increasingly employed such externalized labour for the most menial jobs from the 1970s, and in the case of the RSP, the large majority of these were Adivasis.

It is well established that ‘caste’ or ‘tribe’ entrenches the position of Adivasis—as well as Dalits, ex-Untouchables, or Scheduled Castes—at the bottom of labour processes and the class hierarchy in India.Footnote 13 As Jens Lerche and Alpa Shah have recently argued, therefore, the situation of Adivasis as well as of Dalits is a paradigmatic case of what Philippe Bourgois called ‘conjugated oppression’, that is, an ‘experience of oppression transcending the sum of its parts’ deriving from economic exploitation compounded by an ideological domination based on a wider social hierarchy.Footnote 14 Philippe Bourgois coined the concept in his ethnography of labour on Central American banana plantations to analyse the situation of workers at the bottom of the ladder whose brutal exploitation conjugated with the stigmatization they faced as members of an Amerindian ethnic community.Footnote 15 Bourgois argues that ethnicity (or potentially any other cultural notion of difference, such as caste or tribe) and class (as well as divides among workers based on different positions in the production process) are inextricably intertwined or co-constitute each other, and that both form part of the same process of struggle.Footnote 16 Similarly, in this article I show how ethnicity and the caste-tribe divides has co-constituted class as well as factions among steel workers in Rourkela since the 1950s, for example, in the recruitment of labour by RSP, in the labour process, and in labour politics in the steel plant as well as in the wider political and social life in the town. However, the bifurcation of the steel workforce into company and contract workers increasingly set Adivasi workers apart from each other on both sides of the divide. This shows that class gained traction in relation to ethnicity and caste or tribe over time, or that the way they co-constituted each other is subject to historic transformations, and these cannot be grasped when conceptualizing class, ethnicity, and caste or tribe merely as inextricably intertwined, as Bourgois does.

Historical antecedent: The steel plant, the nation, and the region

In the 1950s, Rourkela was a village of 2,000 people set around a sleepy train station in the middle of nowhere along the rail line connecting Howrah (Kolkata) and Mumbai (then Bombay). Rourkela was selected as the site for the country's first public-sector steel plant because of the nearby rich reserves of all the minerals required for steel production, because two rivers guaranteed sufficient water supply for the steel plant as well as the township that had to be constructed alongside the plant to accommodate the steel workforce and their families, and because the place was already connected by rail to Kolkata and Mumbai, the two major centres of Indian industry and commerce.Footnote 17 Rourkela also seemed a perfect fit for the wider developmental agenda of early post-colonial India because it was an ‘elsewhere’,Footnote 18 a hitherto unknown place in India's sparsely populated internal periphery. This meant that RSP could not rely exclusively on local labour, but had to recruit from all over the country. It was part of the vision for RSP and for public-sector industries at large that their workforces would unite workers from various regional backgrounds as well as religious and caste backgrounds. Steel plants such as RSP and their attached townships were supposed to form melting pots that would produce not only steel but also ‘mini Indias’ that would stand as a model for the nation as a whole.Footnote 19 This transformation was not to happen sui generis, but under the guidance of the state whose industrial undertakings were to provide formal employment, thus granting workers relatively good wages, job security, working conditions, and the right to unionize, and would do so on a mass scale.Footnote 20

However, the arrival of RSP exacerbated existing conflicts between regional ethnic groups and it also produced new ones. This began when RSP was still under construction and formal workers were yet to be employed in significant numbers. For the construction of RSP, Hindustan Steel Ltd (HSL), the public-sector holding company established by the Government of India, contracted a consortium of West German steel manufacturers and some large Indian construction companies.Footnote 21 All construction workers were employed on temporary contracts, but under starkly varying conditions. Skilled operators for the machinery, welders, and electricians as well as supervisors often earned very good wages by local standards, but not the large numbers of unskilled workers employed to clear the ground or to assist the skilled workers. Whereas the former also enjoyed relative security of employment during the years of RSP's construction, the latter faced large-scale retrenchments whenever preparatory or foundation work was completed. Skilled workers were usually migrants from Punjab, Bihar, Bengal, and South India. Adivasis from Rourkela itself, from the surrounding region, or from neighbouring districts were only employed as unskilled workers, though West German engineers praised them for their raw, unspoiled nature, who could therefore be more easily moulded into good workers than others.Footnote 22 Odia who came to Rourkela from Odisha's coast also found employment, but only as unskilled construction workers, and although Adivasis were also involved, it was primarily Odia workers who vented their anger at ‘foreign’ oppressors from Bengal, Punjab, and South India in regular bouts of violence while RSP was under construction.Footnote 23

Although in less violent form, ethnic conflicts persisted when RSP started operations from 1959 onwards, recruiting a regular workforce to run it and retrenching the construction workforce. Also among the regular workforce were skilled workers who were migrants from other states, whereas Odia, and especially Adivasis, were primarily employed as unskilled workers (khalasi). When talking to Odia and Adivasi workers of that time about their work experiences, they frequently complained that these skilled operators from Punjab, Bengal, and Bihar were in cahoots with the equally foreign executives who had often recruited them, and that they were therefore able to dump many of their tasks on them, the unskilled local workers.

Union politics entrenched the conflict between locals and migrants. Workers in undertakings with more than a hundred workers have the right to organize in unions, and the union with the largest number of members among the workforce was entitled to represent it in collective bargaining with management. Especially in the 1960s, rivalries to attain this status as RSP's ‘recognized union’ was fierce. Unions that were able to demonstrate that they could strike good bargains with management had an advantage in attracting members. RSP workers from that time, whom I met in Rourkela, all told me that in their hearts most workers favoured other unions, but that in the end most joined the union affiliated to the trade union umbrella association of the Congress party that ruled in India and in Odisha then. The RSP branch of that union was run by two Punjabi unionists. Odia and Adivasi workers accused them of favouring their Punjabi compatriots and other ‘foreigners’ occupying the skilled positions, while turning a deaf ear to the grievances of local workers. In due course, conflicts between migrant skilled workers and unskilled local ones led to bitter factionalism within the Congress union as well as equally bitter rivalry between it and its main contending union that was led by an Odia.Footnote 24

The composition of the workforce and, related to that, labour politics in RSP changed in the late 1960s. At that time, RSP expanded production and increased its manpower. The pay-scales of public-sector workers also began to really surge, thus increasing the gap between them and workers in other industries.Footnote 25 Consequently, RSP was not short of job applicants, but rules governing recruitment in public-sector industries had also changed. In 1968, the Government of India obliged public-sector undertakings to recruit their manual workforces through employment exchanges. The latter are under the jurisdiction of union states which granted the Odisha state government control over the recruitment of labour for RSP. From the start, the state government of Odisha had aimed to grant ‘sons of the soil’ preferential access to jobs in the prestigious industry in its territory. For that purpose, it had argued that public-sector industries were supposed to foster the development of particularly ‘backward’ regions, not only the nation as a whole, and that RSP jobs should thus primarily go to people from Odisha, not to long-distance migrants from Punjab, Kerala, or West Bengal.Footnote 26 Until 1968, RSP management rejected such claims on the grounds that they already had taken on enough locals, and that they could not afford to take on more because they lacked skills. By contrast, many Odia RSP executives and workers claimed Odia were as skilled as any others, and that it was because of sheer discrimination that the predominantly non-Odia executives preferred to recruit their co-ethnics. However, with the changes in recruitment rules, the tide turned. The Odisha state government officers staffed at the Rourkela exchange saw to it that most of the workers recruited from 1968 on were ‘sons-of-the-soil’ from Odisha. As a consequence, the latter started to outnumber other ethnic groups among the RSP workforce.

Odia then also gained the upper hand on RSP's shop floors, not only because of their larger numbers, but also because they dominated both labour politics and the ‘recognized union’ in RSP, that is, the union entitled to represent the workforce as a whole. In order to act as a ‘recognized union’, a trade union is required to represent the majority among the unionized workers of an undertaking. Which union holds this majority is ascertained by the labour department of the state government and all my interlocutors in Rourkela believed that good relations with the state government are more decisive for a union to become recognized than workers’ support. As long as the Congress party was in power in Odisha, the Congress union enjoyed good relations with the state government and was awarded the status of RSP's recognized union. However, shortly after the Congress lost the Odisha state assembly elections in 1967, a new union emerged as the recognized one in RSP. The party that won the 1967 elections was committed to asserting the state's interest in Rourkela with more zeal,Footnote 27 and the union subscribed to this agenda as well. From the shop floor to the plant level, it was almost exclusively staffed with Odia. Although many Odia did not feel well represented by this union, the non-Odia workers I talked to called the new union an ‘Odia union’, run by Odia and for Odia workers first and foremost.

It is important to note that Adivasis had also applied for the new RSP jobs in the late 1960s, but they did not enjoy the same amount of state patronage as the Odia. In the Odia imagination, Adivasis were sons-of-Odisha's-soil as well. In contrast to the Odia, they did not belong by virtue of their ethnicity, but only in a territorial sense, when they had been born and brought up in Odisha, not in Jharkhand (then still part of Bihar) or the southern parts of West Bengal where the same ‘tribes’ settle as in the northern parts of Odisha. Many Adivasis passed the test of autochthony (for example, by proving fluent in Odia) and were recruited then. However, many more were left out, not because they were not local, but because the Odia staffing the state's administration favoured their ‘own’ people. This angered Adivasis even more since they considered themselves the true locals in the region around Rourkela. Many of them had also lost their land when the state government acquired 20,000 acres for the construction of the steel plant and the township in the 1950s. Back then, they had protested against their displacement and raised demands for better compensation. As a result, they were promised one job per displaced household in RSP in addition to money, a house plot in resettlement colonies around Rourkela, and agricultural land further away. However, by the late 1960s many of the promised jobs had still not materialized, the displaced people complained. They also claimed that the number of households had in fact been much higher than recorded, and RSP therefore ought to provide jobs to many more of the displaced. The displaced people organized protests, approached politicians, and staged demonstrations and sits-ins. In their wake, the then steel minister of the central government reprimanded RSP and demanded that it fulfil this promise, which it did by employing around 300 Adivasis right away.

The leaders of the protest were closely connected to the Jharkhand Party that called for the formation of a separate ‘tribal’ state and the inclusion of the predominantly Adivasi regions around Rourkela into that state. Separate statehood was supposed to protect the interests of the region's Adivasis against exploitative upper-caste strangers (diku). Adivasi RSP workers sympathized with the larger struggle for ‘tribal’ autonomy as well as with the protestors, and they also joined the demonstrations in numbers. Their sympathy and solidarity derived from the discrimination and exploitation they experienced in the hot shops in RSP at the hands of diku executives and co-workers alike. It also derived from the fact that Adivasi RSP workers, both locals and migrants, lived in the same neighbourhoods as displaced people who demanded RSP jobs as well as with other informal sector workers. Although RSP maintains a company township for its workforce, it could only accommodate 24,000 out of its 37,000-strong workforce in the late 1960s, and it turned into a place for non-Adivasi RSP workers from Odisha's coast or other states. Adivasi RSP workers, by contrast, largely lived in the resettlement colonies or in basti, that is, ‘settlements’ that were in fact villages-turned-slums on the fringe of Rourkela. Although they could also have applied for quarters in the township, they preferred these areas as the houses they had there were larger (even though they lacked access to electricity and running water) than the ‘cheap type’ one-room quarters low-grade workers were allotted in the township. They also did not feel comfortable in neighbourhoods dominated by the very same upper-caste people who discriminated against them in the plant and everywhere else.Footnote 28

These narratives show that RSP employed local and migrant workers, as the planners had envisioned. However, differences between local and migrant workers do not map in a straightforward fashion on differences in the way in which workers were subject to, or could resist, labour control. The reason for this is that, in contrast to what Ghosh describes for colonial eastern India, in Rourkela localness did not necessarily entail access to alternative resources. Most Odia and Adivasi workers could certainly retreat more easily to their native villages and fields that were nearby or only a one-day journey away than could the long-distance migrants from Punjab, Kerala, or Bengal. However, not all of them had fields and many locals from Rourkela itself had also lost their entire villages when the state acquired land for the construction of the plant and the town. In general, it is said that control was in fact relatively lax in RSP because public-sector employment offered high job security and also because the plant was heavily overmanned. Originally, it was calculated that RSP would require 15,000 workers,Footnote 29 but by 1965, it was already employing 25,000, and that number went up to 37,000 after new production departments were opened in the late 1960s. For that reason, RSP could afford to take benign attitude to the high rates of absenteeism during these decades. Disciplinary action against absentees was usually confined to wage deductions, and only rarely led to retrenchments.Footnote 30 Because of job security and the relatively generous pay, jobs were highly sought after. However, the narratives further suggest that labour control was nevertheless not as relaxed for all workers, and the major resource for alleviating labour control was patronage by those higher up in RSP or in the state administration. Odia and Adivasi among the first generation of RSP workers claimed that they were subject to much harsher control and they were compelled to do more menial work than long-distance migrant workers, because most supervisors and executives were themselves long-distance migrants with the same regional-ethnic background. The situation changed from the late 1960s onwards when Odisha state and Odia nationalists gained more influence in RSP and patronized Odia workers. By contrast, for Adivasi RSP workers, both local and migrant, the situation remained the same, because they continued to lack connections to or patronage by authorities in RSP as well as the state.

The trajectory also displays a similar trend to the one Philippe Bourgois depicts for the Central American banana plantations. He shows how one Amerindian community, the Kuna, managed to mobilize its close-knit communal bonds and relatively good relations with the state as a political resource which enabled community leaders to negotiate more favourable terms of employment for its members with plantation management. Over the course of a few years Kuna workers therefore climbed the occupational ladder, moving from harvesting to low-prestige but ‘soft’ jobs in the packing plant and in services, and they thereby simultaneously climbed the ethnic hierarchy prevailing on the plantations.Footnote 31 By contrast, workers from another Amerindian group, the Guaymi, lacked political institutions since colonial conquest had destroyed them and they remained historically isolated from the Panamanian state as well as wider society. As a consequence, they remained stuck in harsh harvesting jobs which reinforced their place at the bottom of the local ethnic hierarchy, and they thus experienced their situation as conjugated oppression.Footnote 32 Similarly, in Rourkela, the Odia, with the help of the Odisha state, succeeded in mobilizing politically on ethnic grounds and secured for themselves, first, privileged access to jobs in RSP and, second, privileged positions within RSP. Adivasis, by contrast, remained stuck at the bottom of the hierarchy among RSP workers, in occupational terms as well as in terms of ethnicity—or, in their case, caste—not so much because they lacked political organization but because they were rendered marginal in the regional state-formation project.Footnote 33

The ethnographic present: Adivasis and RSP's hot shops

The above scenario describes the situation between the 1950s and 1990s. In many important ways, it had not changed much when I started my ethnographic research in Rourkela in 2004. RSP still employed Adivasis in relatively large numbers. According to estimates by senior personnel managers, between one-fourth and one-third of RSP's total workforce were Adivasis.Footnote 34 Furthermore, everybody agreed that RSP still deploys Adivasi workers to a large extent in workplaces with the hardest working environments—the coke ovens, the blast furnaces, and other departments in the iron-and-steel zone. I talked about RSP management's obvious preference for deploying Adivasis in these specific worksites with dozens of individuals during the years of my research in Rourkela. In a conversation I had one afternoon in 2007 with two Odia rank-and-file members at a local trade union office, one explained, barely looking up from his newspaper, that Adivasis are largely ‘uneducated’ and therefore a good fit for workplaces requiring more brawn than brain. This was the typical answer given by non-Adivasis that I had by then already received dozens of times from various RSP managers, workers, and unionists.Footnote 35 However, the notion that Adivasi workers stand out as ‘uneducated’ was at odds with empirical social realities for two reasons. First, retired executives and workers as well as old unionists repeatedly told me on other occasions that the vast majority of the first generation of regular RSP workers recruited in the 1950s and 1960s had no or only a handful of years of formal schooling to their credit. The Adivasis among them thus barely stood out in that regard. Second, in 2004, when I started my ethnographic research in Rourkela, on average, RSP workers had much higher educational credentials. RSP had undergone technical modernization between the late 1980s and early 1990s, when some old departments were phased out or upgraded and some new ones established. Already a few years prior to modernization, RSP restricted recruitment to skilled workers and demanded that applicants had a minimum qualification of school graduation after tenth grade, but preferred applicants who had completed vocational training or even college. The only exceptions from this rule were ‘displaced people’, that is, workers whom RSP agreed to recruit in the wake of ‘displaced people's’ protests. Their protests had again revived in the early 1990s after which RSP promised to employ another 1,000 workers from displaced households that had not yet been compensated with employment.Footnote 36 Since the bulk of these were Adivasis, they also formed the majority among RSP workers with below-average qualifications. Nevertheless, the censuses I took of different RSP work groups revealed that most Adivasis recruited since the 1990s had completed vocational training or graduated, and hence had qualifications on par with everybody else.

In contrast to the Odia unionist, Adivasis voiced different notions as to why so many of them were posted in RSP's hot shops. Thus, Bidyut Mundari, an Adivasi engineer from the Mundari ‘tribe’ holding a high position in RSP's captive power plant, told me that a friend of his, an Adivasi from the Kharia ‘tribe’ and senior officer in the Personnel Department, had once confided that management placed Adivasi workers in the iron-and-steel zone by design; and that they do so because ‘the plant has to run’. He then elaborated that in order to bear the heat and dust in the iron-and-steel zone, workers posted there must drink, and because everybody takes it for granted that Adivasis drink, they are understood to be inherently suitable for working there and thus keeping RSP running.

These statements show that the position of Adivasi workers in RSP's production process is as much informed by persistent upper-caste notions of their cultural ‘otherness’ as by their class position. The executive ranks that had the discretionary power to post workers in their respective shops were overwhelmingly staffed by upper-caste individuals. The other unionist involved in the conversation about the situation of Adivasi RSP workers in the union office on that afternoon in 2007 was also well aware of this. As he told me, in obvious disagreement with his comrade, Adivasis work in the hot shops simply because executives hold ‘certain concepts’ about them. He did not think it necessary to elaborate on what these concepts were, and being familiar with the usual stereotyping of Adivasis outlined in the introduction to this article, I also did not enquire further. When reflecting on the conversation afterwards, it came to my mind that this unionist was a Dalit, that is, from an ex-Untouchable or Scheduled Caste background, not from an upper caste as was his comrade who called Adivasis uneducated; and I wondered whether his awareness that managers’ caste prejudices heavily impact on one's position in RSP derived also from his personal experience and not just from observing the careers of Adivasi workmates.

Drinking, working, and shirking in Rourkela

Adivasis in RSP nevertheless struggle to dissolve or reframe the co-constitutive relation between their ‘tribal’ background and their position in the production process. For Adivasis, drinking was indeed a key part of their sociality and was perceived by them as central to what distinguished them from the upper castes. Many rituals require that deities and ancestral spirits are offered small cups of rice liquor (illi rase) and that the worshippers consume some liquor afterwards as well. The more generous offering of other drinks, traditionally either desi or ‘country liquors’, such as the mild ‘rice beer’ handia, or the stronger, distilled liquor arki, or (nowadays) also often industrially produced and much more expensive Indian-made ‘foreign liquors’ such as whiskey or rum, is the usual way to show hospitality to (male) guests. However, many Adivasis in Rourkela also claimed that in rural areas people drink more moderately than in town and that heavy drinking is in fact a corollary of the region's industrialization.Footnote 37 I often heard complaints about the excessive drinking of the now older men after they joined RSP or other industries in the 1960s and 1970s, how after paydays they used to throw parties for each and every visitor, with liquor and chicken, at any time of the day and night, or else spend their money on women. In these stories, the older generation is portrayed as unaccustomed to regular work and monthly wages or even to handle sums of money greater than Rs 20.Footnote 38 Others said that the problem with drinking is the adulteration of liquor by large distilleries which occurred when the first industries arrived in the region and was unknown when people produced liquor at home for their own consumption or for their immediate neighbours. Many also claimed that though their fathers and uncles consumed alcohol daily, they drank within limits. Ladra, for example, made it a point that his father, whom RSP recruited in 1978 to work in the coke ovens, always drank only one or two glasses of arki after he returned from work and that he had rarely been absent. Furthermore, his father, like he himself as well as many other desi drinkers today, had taken care to avoid the industrially produced arki that they suspected to be adulterated. By contrast, arki that is clean (sopa) helps to clear the throat of the dust one is exposed to in the coke ovens (but also other hot shops) and this was why Ladra's father as well as his Adivasi workmates in RSP's hot shops drank it after work. As mentioned above, Adivasis drank for other reasons too, of course. Nevertheless, Ladra's and others’ claims that Adivasi workers drank as a remedy against the hazardous working conditions they faced in RSP's hot shops, that the way they drank was a result of the way they were (and are) put to work in the steel industry are important. They thereby reject their stereotyping by others as drinkers first and workers second. It also shows that Adivasi RSP workers were convinced that they owe their position within the RSP labour process to caste prejudice among those in a powerful class position, not to their alleged lack of ‘education’ and ‘sobriety’.

At the same time, Adivasis were also convinced of their innate distinctiveness, a distinctiveness that transcended differences of ‘tribe’ that they otherwise considered important when it came to marriages and rituals. In their talk, it was almost always the Odia who were presented as the ‘other’, not the Bengali, Bihari, or Punjabi; and one important respect in which they took them to differ was work. Regardless of ‘tribe’, class, age, gender, and education, Adivasis claimed that Odia are unable to work hard. They said dismissively that Odia kati paru nahanti (‘they cannot slog'), and that they are kam chor guda (‘shirkers’, lit. ‘work thieves’) and tokota (‘cheats’). They themselves were the opposite of this: hard and diligent workers. Of course, it was not only Adivasis who claimed a special propensity for hard work. I heard Biharis making the same statement as well as Odia from the south Odishan Ganjam district. It is not very surprising that in an industrial milieu such as Rourkela work is important in how people identify themselves and others. Given that RSP had exacerbated, not attenuated, the importance of ethnic and caste identifications, it is also not surprising that they play a crucial role in this, too. However, as has been shown in several ethnographic and historical studies, ethnicity, class, and gender are not neatly bounded categories that merely interact on industrial shopfloors, but instead create and recreate each other in these contexts in specific, though never uncontested, ways.Footnote 39 Also in Rourkela, work is an important arena in which people struggle about ethnicity or caste (or ‘tribe’). Adivasis claim that they staff the hot shops because they are exceptionally hard workers, not because they are heavy drinkers or lack education. Furthermore, the hot shops are the ‘mother departments’, as they called them, on which the whole production process depends. Since it is them who really work there (even if some others are also posted there), it is on their labour power that the whole undertaking rests, while others merely live off the fruits of their labour. They thus claim to be at the centre of the modern industrial undertaking, not ‘primitives’ employable only for peripheral rough jobs, as others present them; they therefore aim to reframe the very meaning of who Adivasis are. However, as I show in the following section, the politics Adivasi workers pursued to this end also laid bare differences among them.

The uneducated, the educated, and the savvy

Beyond their shared understanding of being hard workers (and the Odia not), the views Adivasis expressed on their working lives in RSP of course differed somewhat from person to person, but they were also markedly different depending on their generation and educational background. The older, now retired, Adivasi workers who had been recruited during the 1960s at times also described their working life in RSP as a ‘torture’ (using the English term). Officers, supervisors, and even some fellow workers, especially union shop floor representatives, made them work without breaks, and also in tasks that actually had not been assigned to them, and when it came to promotions, they were overlooked. For that reason, there were several who quit, but if one wanted to remain employed, one had to adjust. They lacked ‘relations’, that is, patrons higher up the echelons, and were unable to establish them because telo mariba (literally ‘to apply oil’, ‘to anoint someone’) is not the way they go about things. That is something sycophants (camca) do to ingratiate themselves with others higher up the ladder, by humouring them or doing them favours. They, as Adivasis, would not even know how to do that, but their Odia workmates are highly skilled in telo mariba with supervisors, officers, and union leaders. Therefore, they can afford to stand around, hands in pockets, and watch others toiling away.

The Adivasis who were working for RSP during the time of my ethnographic research had been recruited later. The older workers, who were in their fifties and relatively close to their retirement at 60 when I met them in the 2000s, had been taken on in the early 1970s. The large majority of Adivasi RSP workers with whom I socialized had been taken on in the 1990s. They shared the view that they, as Adivasis, are naturally disinclined to sycophancy and shirking, which is of course a corollary to their self-perception as hard and honest workers. They took equal pride in claiming that others are no longer able to boss them around or to cheat them, because they, in contrast to the retired elders, had buddhi. The term translates as ‘brains’, ‘intellect’, and ‘knowledge’, but my interlocutors were emphatic that it is different from ‘education’ and that it does not necessarily come with it.Footnote 40 In a few conversations, workers used the term when emphasizing the contrast between the book-knowledge engineers had of work processes and machinery against their practical, experience-based knowledge. More often, buddhi was about one's ‘savviness’ in grasping both the formal regulations in RSP as well as the informal arrangements. The same is true for dealing with the state administration, the police, or an insurance company, to name some examples. The notion shows that the younger, current generation of Adivasis RSP workers do not regard the state as a malign external force that is best kept at a safe distance, as Adivasis in the nearby rural areas of Jharkhand do.Footnote 41 On the contrary, Adivasis with buddhi claim familiarity with state institutions and other bureaucratic set-ups. The notion that formal education does not bring you as far as familiarity with and proximity to power can also, I suggest, be read as a critique on the emphasis the upper-caste Odia put on education and on the alleged lack of it among Adivasis.Footnote 42

The emphasis they place on buddhi does not mean that Adivasi RSP workers consider formal education unimportant. As mentioned above, since the mid-1980s, RSP only considers job applicants who have completed the tenth grade, but prefers to employ those who have completed vocational training or college. The younger Adivasi RSP workers had these qualifications, and were no less emphatic about them than about their buddhi. They described themselves as ‘technical people’ who did not handle shovels (belca mariba, the prototypical unskilled manual labour in Rourkela) or just pull a few handles as others told them, but who understood their jobs and took them seriously. Most educated Adivasi RSP workers also drank, but, like the educated do, only foreign liquorFootnote 43 and only occasionally, and without bunking off the following day.

Their education and technical understanding as well as their buddhi distinguished the educated and savvy RSP workers from the already retired generation of uneducated RSP workers, but also from some contemporaries in RSP. As mentioned above, RSP made an exception to the qualification standards it set for its workforce in the 1980s and agreed to employ the ‘displaced people’ it took on in the mid-1990s if they had just completed the tenth school grade or even less. The regularly recruited RSP workers, Odia as well as Adivasi, usually talked about them with some contempt. When they called fellow workers ‘displaced’ they implied that they were in fact not qualified for the job. They often accused them of notorious absenteeism and described them as drunkards. Japun Hembram, for example, a Santal who joined RSP's coke oven department in 1992 after graduating in engineering, complained about the lack of commitment of the ‘displaced people’ to their work. Because of that, he said, the rest of the work group often had to take up their work, too, with the result that they had difficulty meeting their production targets. This puts their production bonuses at risk and having ‘displaced people’ in one's work group is hence a nuisance. In fact, he was convinced that an RSP job does not suit such uneducated people and that they should hence not be employed. Kali Mundari, a vocationally trained worker recruited in the late 1980s for the steel melting shop, aired the same views when we met his neighbour on the roadside leading to their basti one afternoon. His neighbour was also a regular RSP worker who had just come back from his shift when he spotted us and rode up on his bike. He had been recruited in the early 1970s with just ten years of schooling and was now close to his retirement. In common with most RSP workers of his age and qualification, he was concerned about his adolescent sons’ prospects of landing a good job, preferably in RSP, and immediately started complaining that they, as the true locals, should demand preferential employment on the grounds of their forefathers’ displacement. Kali, however, rebuked him, stating that ‘RSP nowadays doesn't anymore employ people simply for handling the shovel!’ Once he had left, Kali told me that his neighbour's sons were all ‘useless school drop-outs’.

For many Odia workers, it was self-evident that the displaced people were not a good fit for regular jobs in RSP or, indeed, any other industry. Almost all of them were Adivasis and it was hence to be expected that they would drink a lot and come to work only irregularly. For Japun and Kali, by contrast, it was a matter of class. The school drop-outs were the way they were because they were ‘labour class’, and were therefore only suitable for labour class jobs, not ‘technical’ jobs requiring education and an educated attitude. Both allegations point to a profound reconfiguration of social relations in Rourkela. Earlier, allegedly typical ‘tribal’ behaviour rendered one suitable for work in the hot shops and was no hindrance for a regular job in RSP. Likewise, the earlier ‘othering’ of Adivasi RSP workers on the job made them draw closer to Adivasis outside public-sector employment, not become more distanced. These changes reflect the restructuring of the Indian economy, its public sector, and, in its wake, also the RSP, to which I will now turn.

The wider context: Company and contract workers

In 1991, the Government of India embarked on a policy of ‘economic liberalization’ that was to dismantle some cornerstones of Nehruvian ‘socialism’,Footnote 44 and in its wake to reform public-sector industries. The Government of India declared the nine most promising central government public-sector undertakings, so-called navratna (‘nine jewel’) companies, a status that granted them greater autonomy, in order to make them competitive global players.Footnote 45 Among them was SAIL (the Steel Authority of India Ltd.), a public-sector holding company of which RSP was a subsidiary unit.Footnote 46 For RSP workers, competitiveness did not lower the conditions of their employment, which remained secure. The fringe benefits stayed excellent and wage rates continued to be regularly enhanced: from Rs 2,000 minimum pay in 1992, to Rs 4,000 in 1997 and to Rs 8,630 in 2007.Footnote 47 The wages RSP workers earn, as indeed public-sector workers in general, placed them comfortably in the Indian middle class.Footnote 48

Competitiveness did entail a drastic reduction of regular manpower for all SAIL units and hence of the number of workers able to enjoy privileged public-sector employment. Already in the late 1980s, RSP management labelled 15,000 of its 39,000 regular workers as ‘excess’ and aimed to get rid of 9,000 by the end of 1992.Footnote 49 Since public-sector workers still enjoyed security of employment, RSP could not achieve manpower reduction by retrenchments. Instead, it went for voluntary retirement schemes and, more effectively, it made use of the retirement of the first generation of RSP workers who started reaching their retirement age of 58 in large numbers in the early 1990s.Footnote 50 In their place, RSP recruited not only better qualified, but also fewer workers. Through these means, manning levels for the whole of SAIL came down from 190,000 in 1989 to 117,000 in 2009; and for RSP they came down from 39,000 in 1989 to 22,500 at the start of my research in 2004, and to 15,000 in 2014.

The actual workforces on RSP premises were in fact substantially larger. Already in the early 1970s when the wages of public-sector steel workers had begun to rise significantly,Footnote 51 RSP (as did other steel plants in India) outsourced a growing number of jobs to private contractors who in turn hired contract workers. Over the years, the number of contract workers in RSP grew. In the late 1980s, there were around 10,000, and in 2014, there were 15,000—equal to the number of regular workers.Footnote 52 Contract workers were hired for a daily wage ranging between 20 to 30 per cent of what regular workers earn per day,Footnote 53 and they were hired only temporarily for the job at hand, even though many of these jobs had to be done almost continuously. They were thus more amenable to labour control than the permanently employed company workers, and they were made to do the most arduous and dangerous jobs in RSP, such as loading and unloading, cleaning of shops and machines, or relining of blast furnaces.

As Parry points out, in terms of their respective wages, their work, as well as their consumption habits, their lifestyles, and their aspirations, regular workers in public-sector companies and the contract workers are worlds apart.Footnote 54 Consequently, they are also perceived to belong to a different class—the ‘labour class’, as the middle-class RSP workers and others call them. Furthermore, since the relatively privileged situation of regular workers is, to a certain degree, based on the especially harsh exploitation of contract workers, they also have different, often opposing, interests. As Parry convincingly argues, this suggests that they are indeed perceived to belong to altogether different classes.Footnote 55

The trajectory in Rourkela follows the global trend of labour regimes in the second half of the twentieth century: with a surge of formalizing work in the 1950s giving way to its increasing informalization, especially of unskilled jobs, since the 1970s, and leading to a polarization of workforces into securely employed core and precariously employed marginal workforces.Footnote 56 The process also unfolded in Rourkela along a local logic. Contract workers were primarily Adivasis, from the wider region, from surrounding villages, and from Rourkela itself.Footnote 57 As outlined in the introduction, others presented them as prototypical contract workers. As Adivasis, they have the stamina and capacity to slog, but due to their limited wants and limited brains, well-paid regular employment does them no good. It only makes them drink harder and care even less about the future, their jobs, their money, and their children's education. Again, for most Odia the depiction of Adivasis as a natural-born ‘labour class’ was unproblematic. For Adivasi RSP workers, by contrast, this depiction was problematic and they were keen to disentangle the equation and to present themselves as educated, committed, or middle-class workers and Adivasis.

The emphasis they put on their education, on their attitude as educated technical people, and hence their difference from the ‘uneducated’, was supposed to serve that purpose. Another important means to draw the line between them and the uneducated, undeserving of regular company jobs, was by spatial segregation. Unlike earlier, Adivasi RSP workers recruited since the 1990s settled in the township, not in the resettlement colonies and basti. Thanks to manpower reduction, the township has become large enough to accommodate the whole workforce. Adivasi RSP workers also sought to move there because—as they all unanimously related—basti and resettlement colonies are not the right places to raise children. They are ‘labour class’ spaces where drunkards stagger down the lanes, where adults are foul-mouthed, and where one should not wonder that children do everything but study. In the township, by contrast, neighbours set good examples and create a very different, respectable, and educated, or ‘middle class’, environment.

These middle-class neighbours were still largely non-Adivasis, or in fact Odia. When the first generation of RSP workers retired, the Bengali, Punjabi, and migrants from other states largely left Rourkela. Given the politics of the Odisha state, their children would not stand a chance of securing any of the remaining jobs in RSP, and other industries that offered similar employment opportunities did not exist. Consequently, in the township one spoke Odia, not Hindi, as one might expect in a place supposed to be a ‘mini India’. Likewise, the hoardings were mostly in Odia, if not in English, and the statues honouring Odia freedom fighters and politicians dwarfed the statue of Nehru. However, Adivasis also claimed their space in the township. Some Santali, who are considered more assertive than other Adivasi communities, established places of worship. Adivasis from all communities often decorated their house fronts with pictures of bows and arrows, or of the ‘tribal’ independence fighter Birsa Munda, indicating their Adivasi identity. Adivasi RSP workers and executives organized ‘cultural associations’ to promote the culture of their individual Scheduled Tribe and sometimes celebrated rituals of their respective communities on public grounds or community centres in the township. Through these place-making activities, Adivasi RSP workers claim the space that had so far been inhabited by upper-caste Odia RSP workers for themselves, too, and thus realign the relation of caste and class in space. The township is now primarily a middle-class space, while the Adivasi basti and resettlement colonies they have abandoned or avoided from the start are labour-class, not Adivasi, spaces.

The relationships between Odia and Adivasi township residents seemed to me neither hostile nor intimate, but distanced. On my regular visits to the quarters of an Adivasi RSP worker, children from Odia neighbours sometimes dropped by to meet their children. However, other adults I met there, either other invitees or casual visitors, were usually relatives and if not, other Adivasis. Odia were only rarely among them. The educated Adivasi workers often told me that the upper-caste Odia do not dare to denigrate them openly, because, unlike earlier generations, they are now educated and less shy, but they were convinced that the upper castes still resent them, that inside they still have ‘feelings’, as they said, and that they can tell this from their facial expressions.

The Adivasi visitors I met at the company quarters in the township were usually also RSP workers or employees in other formal-sector undertakings, such as the railways or the electricity board, and hence had a similarly middle-class background. The Adivasi RSP workers settling in the township emphasized how well they still get along with their families and that they regularly visit them. However, these visits were usually paid one-way, not exchanged. The educated township dwellers regularly went to see their parents and other relatives in the village outside Rourkela, or in the basti or resettlement colony in Rourkela, while it was much more rare for the latter to show up at the township quarters. They do not feel at home in the township, township residents told me, because they would have to dress up for the occasion and also because they are not used to dining at tables as one does in the township, but on the floor. I suspect that township Adivasis were not only concerned about the comfort of their uneducated relatives, but also that their presence might hamper their own standing among their educated neighbours in the township.

Adivasis in the basti and resettlement colonies also view the township dwellers in ambivalent ways. They described them as sometimes a bit miserly (kanjus), complained that they contributed less to ritual expenses than they actually could, and that they resembled the Odia diku (‘foreign exploiters’) in their money-mindedness. However, they are not quite like the diku, because they still lack the social relations in the higher echelons in RSP, in the bureaucracy, and in other influential positions that upper-caste Odia allegedly usually have. Similarly, they respected the regular workers for their education, for the education they offered their children, and tried to emulate them in educating their own children, though with much more modest means. They also respected the middle-class Adivasis for their engagement in the Adivasi cultural associations. At the same time, they ridiculed the call of these associations to maintain one's ‘tribal’ language, while the middle-class individuals leading them all sent their children to expensive English-medium schools. Several times, they also pointed out to me behind closed doors that the ‘big’ people had married not strictly according to the rules of endo- or exogamy,Footnote 58 and that this actually disqualifies them from standing as role models for the community. The relations between privileged middle-class Adivasi RSP workers in the township and the precarious labour-class Adivasi informal sector workers in basti and resettlement colonies are characterized by a sense of alienation.

The sense of alienation between them calls to mind the situation Martin Orans describes for India's ‘original’ steel town—Jamshedpur—in the 1950s. Adivasis from the Santal ‘tribe’ with regular jobs in the Tata steel plant lived in the attached company township and the poorer uneducated Santals felt highly uneasy in front of each other.Footnote 59 In Rourkela, the spatial segregation of Adivasi RSP workers from contract workers and other informal sector workers was not only a manifestation of the growing class differentiation between them, but also contributed to that differentiation. It provided the former with access to an exclusive urban environment, with the explicit aim of granting their children better education that would lead to better employment prospects and futures.Footnote 60

However, the move into the township as well as the claims to ‘educatedness’ were not about class alone, but also about ‘caste’, about claiming the privileged urban space, with its amenities and lifestyle, that RSP also provides for Adivasis among the workforce. As historian Frederick Cooper argues with regard to the United States, African-Americans striving to be recognized as middle class do not make a point only about themselves, but engage in a struggle about the very meaning of race and class. By claiming that they are capable of advancing in class terms, African-Americans call into question the existing notions of class and race.Footnote 61 Similarly, Adivasi RSP workers emphasizing their educational qualifications and educated attitude claim that they, as Adivasis, are part of the modern public-sector working class, and thus struggle with the very meaning of Adivasi-ness. Management's emphasis on the need for an educated workforce and the prevailing notion that Adivasis are uneducated gave this struggle importance and urgency. However, the social and spatial distance from the labour class this struggle entailed also threw the inequalities between them into sharper relief and is likely to exacerbate them in the future.

Conclusion: Struggles about class and Adivasi-ness in eastern India

As Anastasia Piliavsky has recently argued, a stereotype in the true sense of the word is a stable idea that is invoked across different historical situations to clad strategic decisions with the moral authority of widely recognized and allegedly timeless truths.Footnote 62 She further argues that stereotypes are only effective in this regard if they are based on relatively simple ideas that allow them to absorb shifts in meaning and to be put to different strategic usages. The notions about Adivasis prevailing in Rourkela are stereotypes in such a true sense. Adivasis in Rourkela, whether locals or migrants, are widely portrayed as drinkers, capable of rough labour, and too uneducated for much else. RSP managers took this as a justification to place them in the most hazardous working environments in RSP's hot shops, and there RSP executives and non-Adivasi workmates made them toil harder than others and in the harshest jobs. Adivasi RSP workers are thus subject to what Philippe Bourgois calls ‘conjugated oppression’, the mutually constitutive conjugation of class-based economic exploitation with ideological domination based—in this case—on caste.

This at least captures the situation during the first decades of the plant's existence. Since the 1990s, the situation has become more complex because the divide between the core workforce of company workers and the externalized peripheral workforce of contract workers grew and gained importance vis-à-vis the caste or caste-tribe divide in RSP. To be sure, though on a lower scale, RSP has externalized labour since the 1970s. Furthermore, regular RSP workers with an Adivasi background nowadays face the same stereotypes as the older generation: they still find themselves posted disproportionally in the hot shops, and the working environment there is still tough in comparison to the mills. However, thanks to technical modernization in the 1990s, it is less hazardous than it used to be in earlier decades. More importantly, the unskilled and harshest jobs in these departments are not done any more by RSP workers, nor by the Adivasis among them, but by contract workers. Contract workers form a different class from company workers because of the large differences between them in terms of working conditions, wages, and security of employment. Contract workers in Rourkela are also predominantly Adivasi and in their case, the stereotyping of Adivasis serves to argue that regular employment allegedly does not suit uneducated habitual drinkers and that precarization was hence no harm for them. Thus, there are now two classes of workers in RSP and these do not overlap with differences of caste or with the caste-tribe divide, and only Adivasis in one of them—the contract workforce—suffer from conjugated oppression, but no longer those in the company workforce.

As their already disproportionate presence in the hot shops reveals, an Adivasi background has not lost all relevance for the position of Adivasi RSP workers in the company. The reason for this lies in the fact that, despite the many privileges Adivasis with regular employment in RSP enjoy, they are predominantly workers, not executives. They are thus under the discretionary power of upper-caste individuals who primarily comprise the executive ranks, and this adds decisive weight to the stereotyping of Adivasis as uneducated and as good only for rough, unskilled jobs. It also rendered their struggle to prove their rightful belonging to the educated company workforce not only as an urgent but also an uphill task. As I have also shown, this struggle is as much about Adivasi-ness as it is about class. It crucially builds on the social and spatial distancing of educated middle-class Adivasi RSP workers from the uneducated ‘labour class’, and thereby exacerbates the inequalities between them.

The trajectory in Rourkela thus shows that class and positions in the production process remain intertwined with prevailing social hierarchies or cultural notions of difference, as Bourgois theorizes in his concept of conjugated oppression. The trajectory also shows that the form the intertwinement takes has undergone crucial changes over the last decades. Since RSP's manual workforce has become almost exclusively composed of people from Odisha—thanks to the interference of Odisha state—ethnicity has lost its importance in shop floor relations and union politics. By contrast, caste or an Adivasi background remains important, but it intertwines with quite different class positions that have evolved among the workforce over the last decades. Bourgois’ concept of conjugated oppression unfortunately fails to explain such changes. Despite its merits in foregrounding the intertwinement of class and cultural notions of difference, the concept does not shed much light on the way they intertwine and under what conditions this intertwinement changes.Footnote 63 As I have shown in this article, India's turn to economic liberalization and the concomitant reform of public-sector industries were essential for the growing bifurcation of the steel workforces in Rourkela as well as the growing class differentiation among Adivasi workers. This is not to fall back into the economic determinism against which Bourgois (as well as Lerche and Shah)Footnote 64 rightly and powerfully argues. For Adivasi workers in Rourkela, as presumably also for Adivasis elsewhere, struggles about class are indeed always simultaneously struggles about Adivasi-ness. However, the way they struggle about Adivasi-ness reflects the growing class polarization among Adivasis in Rourkela and, in fact, further marginalizes those at the bottom of the class hierarchy.

Acknowledgements

My ethnographic research in Rourkela extended over roughly 32 months conducted intermittently between 2004 and 2014. I gratefully acknowledge the support of the German Research Council DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft), and the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology. I furthermore remain indebted to Rajat Singh, Zoober Ahmed, and Ganesh Hembram for their invaluable research assistance, as well as to the editors of this special issue Vinita Damodaran and Sangeeta Dasgupta, to the two anonymous reviewers of MAS, and to Katharina Schneider for their critical comments on earlier versions. The usual disclaimers apply.

Competing interests

None.