Historical and cultural heritages tell vivid

stories of the past and profoundly influence

the present and future.

—Xi JinpingIntroduction

A Google Scholar search of the term ‘Maritime Silk Road’ gives over 24,000 hits. While most of the studies listed on the search platform focus on the geopolitical and economic implications of the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI; originally the ‘One Belt One Road’ or OBOR) project associated with the term, there are also publications that explain the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ in a historical context. Frequently in the publications dealing with the term’s historical context, the centrality of China in Indian Ocean interactions is asserted and the importance of Chinese ports, actors, and objects (even when not related to silk) emphasized. One recent example is the journal article entitled ‘The rise of the Maritime Silk Road about 2000 years ago: Insights from Indo-Pacific beads in Nanyang, Central China’, which starts with the following lines:

The Maritime Silk Road connects East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, West Asia, East Africa, and the Mediterranean Sea. This road was established under the influence of the political environment of China in antiquity. (Xu, Qiao and Yang: Reference Xu, Qiao and Yang2022: 1)

The current article examines the origins of such China-centric narratives of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ in the 1960s and its various entanglements since the early 1980s involving the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) political bodies, academia, the ‘open-door’ policy, the pursuit of World Heritage listings, and the ongoing BRI project launched by the Chinese president Xi Jinping (1953–) in 2013.Footnote 1 These entanglements over the past four decades or so, the article contends, have resulted in the establishment of what could be called a ‘Maritime Silk Road’ ecosystem in the PRC. The analysis of this ecosystem reveals the processes through which a narrative on China’s engagement with the maritime world has been constructed over time as well as its association with a host of other issues, including national pride, heritage- and tradition-making, foreign-policy objectives, and claims to territorial sovereignty. Despite the proliferation of publications on the topic, these entanglements of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ with the recent history of the PRC have not yet been explored. The objective of this article is to address this lacuna.

The inspiration for those who invented the term ‘Maritime Silk Road’, as the next section outlines, was the late-nineteenth-century phrase ‘Silk Road(s)’ (as die Seidenstraße/Seidenstraßen), often attributed to the German geographer Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen (1833–1905).Footnote 2 Since the early twentieth century the latter term has inspired academic writing and travel diaries, led to the making of documentaries and films, and provided states and transnational organizations with a metaphor by which to further their respective political, economic, and cultural objectives. Tamara Chin (Reference Chin2013: 194–195) has pointed out that the ‘Silk Road provides a model of idealized exchange’ and ‘offers a kind of geopolitical chronotope, that is, a condition or strategy for geopolitical thought and action, as well as a background context’. This observation applies just as much to the term ‘Maritime Silk Road’, not only because it is inspired by the nineteenth-century label, but also because it has gained similar currency with nation-states, international organizations, academics, and publishing houses.

In Japan, the concept of the ‘Silk Road(s)’ (as Shiruku Rōdo シルクロード, a transcription of the English term) became popular after the Second World War as a way of reconnecting with the Eurasian continent politically and culturally (Esenbel Reference Esenbel and Esenbel2018: 13–14). Reconnecting to the outside world, including through the newly emerging Afro-Asian initiatives during the 1950s, was also the context within which, as Chin (Reference Chin2013, Reference Chin2021) further demonstrates, the term ‘Silk Road(s)’ (as Sichou zhi lu 絲綢之路) entered the PRC state’s media vocabulary and academia. In addition to serving a similar reconnecting function, the notion of a ‘Maritime Silk Road’ provides a sense of belonging to both Japan and the PRC, which are often considered peripheral regions of the Indian Ocean world.Footnote 3 Especially in the case of the PRC, the concept is used to assert not only China’s involvement with, but also its centrality in, exchanges across the Indian Ocean over the past two millennia.

While in Japan the idea of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ was eventually supplanted by a more conceptual analysis of ‘maritime history’ (kaiiki-shi 海域史) in the 1990s,Footnote 4 in the PRC the former term (rendered as Haishang Sichou zhi lu 海上絲綢之路) rapidly won increased popularity after being proposed for the first time in 1981, and by the mid-1990s it was sparking national interest and pride. It has since been used by a broad spectrum of stakeholders in academia, cultural institutions, and government organizations to portray China’s ‘peaceful contributions’ to Indian Ocean interactions, in contrast to the violence inflicted by European colonizers. This China-centric conceptualization of Indian Ocean interactions frequently appears in Chinese academic and state discourses in the modified form of ‘China’s Maritime Silk Road’ (Zhongguo Haishang Sichou zhi lu 中國海上絲綢之路; emphasis added). More recently, as part of the BRI project, the term, used in conjunction with ‘Silk Road’, has been interpreted as a way of ‘smoothing’ (Winter Reference Winter2019) and ‘rebranding’ (Pu Reference Pu2019) the PRC’s image in foreign relations. This incorporation of the ‘Silk Road’ and the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ under the BRI rubric, where ‘Belt’ denotes the former term and ‘Road’ the latter, has blurred (especially for those unfamiliar with the discourse within the PRCFootnote 5) the distinct origins, connotations, and applications of the phrase ‘Maritime Silk Road’. It has been used domestically, for instance, to endorse the PRC’s ‘open-door’ policy, and officials, museums, and scholars based in several coastal cities of the PRC had emphasized it in their efforts to acquire UNESCO World Heritage listings even prior to the launch of BRI. These various entanglements of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ idea with PRC stakeholders are the main issues analysed in this article.Footnote 6

In the sections below, I argue that these entanglements between academia, coastal cities, the nation-state, and UNESCO were instrumental in constructing and promoting a China-centric history of Indian Ocean interactions by invoking the term ‘Maritime Silk Road’. As such, the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ must be understood as a concept that is intimately associated with the recent history of the PRC, connected to the construction of the country’s maritime heritage, and employed to serve the geopolitical agenda of the state in the South China Sea region. It is therefore distinct from the nineteenth-century term associated with Richthofen with respect to its geographical focus, intellectual discourse, and policy applications, most of which took place within or relate exclusively to the PRC.

The key conceptual framework employed to unpack the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ ecosystem is Eric Hobsbawm’s ‘invented tradition’, which ‘is taken to mean a set of practices, normally governed by overtly or tacitly accepted rules and of a ritual or symbolic nature, which seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behaviour by repetition, which automatically implies continuity with the past’ (Hobsbawm [1983] Reference Hobsbawm, Hobsbawm and Ranger2012: 1). However, the concept is expanded in this article to include important modifications made by some of Hobsbawm’s critics who have suggested that ‘the term “invented traditions” means rather selecting, choosing, reinforcing, stressing, emphasizing or institutionalizing some of the existing or old traditions, than really inventing new ones’ (Farkas Reference Farkas2016: 35). Unlike the term ‘Silk Road’, which was imported into China, recognized as ‘a neologism of European geographers’ (Chin Reference Chin2013: 217), and then appropriated by the Chinese state and academia during the 1970s,Footnote 7 the term ‘Maritime Silk Road’, although initially conceptualized by a Japanese scholar (see below), developed entirely within the PRC. This article demonstrates the processes of ‘selecting, choosing, reinforcing, stressing, emphasizing and institutionalizing’ associated with this development. It was only through following these processes and internal gestations that the idea of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ eventually became entangled with the broader geopolitical and ‘geocultural’ agendas of the state, including the BRI project.

This ‘invention’ of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ idea, and especially the adage ‘China’s Maritime Silk Road’, the article contends, originates with the Qing (1644–1911) intellectual Liang Qichao’s 梁啟超 (1873–1929) early twentieth-century ‘choosing’ of the Zheng He 鄭和 (1371–1433) expeditions (1405–1433) and the spread of Chinese diasporic communities as highlights of premodern China’s maritime engagements (Liang Reference Liang1904). Liang made this choice after the Qing navy had been overpowered by the Western colonial powers and imperial Japan. His resurrection of Zheng He served to nurse the pain of these instances of national humiliation.Footnote 8 Liang’s views were reinvented during the 1980s by Chinese intellectuals, inspired by the imported nineteenth-century term and stimulated by the government’s ‘open-door’ policy to undertake the study of and thus accentuate premodern China’s contributions to the maritime world through trade, diplomacy, and the peaceful spread of diasporic communities. As the PRC’s economy started to burgeon in the late 1990s and the 2000s, and as UNESCO began recognizing its cultural heritage sites as a way of promoting its own agenda of East–West harmony, this intellectual narrative of China’s maritime engagement was ‘reinforced’ by nationalist knowledge production and propaganda systems. A consequence of this was the ‘institutionalization’ of the China-centric narrative by the Chinese state, now firmly established within the BRI project. Thus, the article reveals how, over time, a range of circumstances, influences, agendas, and stakeholders, both domestic and foreign—all part of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ ecosystem—resulted in the invention, reinvention, and imagination in the ideas, research, representations, and politics concerning the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ in the PRC.

Also important for the unpacking of the ecosystem are the concepts of ‘heritage-making’ and ‘museum effect’ outlined by Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett (Reference Kirshenblatt-Gimblett1995, Reference Kirshenblatt-Gimblett1998), which appear in the curating of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ narrative in national and international exhibitions organized by museums and government authorities in the PRC. Similarly, the idea of ‘friction’ put forth by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing (Reference Tsing2004) applies to the tensions evident in the deliberations between Chinese and foreign scholars over the role of China in Indian Ocean connections, in the debates over the politics of the ‘open-door’ policy in the PRC, and in the pursuit of UNESCO World Heritage listing by contending Chinese coastal cities. Together with Prasenjit Duara’s (Reference Duara2003) ‘regime of authenticity’, the issue of ‘friction’ also manifests in the PRC’s assertion of territorial sovereignty by claiming cultural ownership in disputed regions of the South China Sea, and in its efforts to claim exclusive possession of underwater heritage. These concepts and their applications are discussed later in this article. We begin by examining the origins of the term ‘Maritime Silk Road’,Footnote 9 around which the history and heritage of China’s engagement with the Indian Ocean world was constructed, reinforced, institutionalized, and propagated globally.

The inventors of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’

In October 1991, the overseas edition of the People’s Daily published an article by Wang Xiang 王翔with the title ‘Who First Proposed [the term] “Maritime Silk Road”?’ Wang (Reference Wang1991) maintained that it was the Japanese scholar Misugi Takatoshi 三杉隆敏 (1929–) who coined the term in 1979, but he was only partially correct. It was actually the French scholar Émmanuel-Édouard Chavannes (1865–1918) who, in 1903, made a passing reference to ‘the way of the sea’ (la voie de mer) through which Chinese silk was exported to Europe via South Asian ports (Chavannes Reference Chavannes1903: 233). Misugi used the term in 1968 (not 1979) in his book entitled Umi no Shiruku Rōdo o motomete: Tōzai yakimono kōshōshi 海のシルクロードを求めて: 東西やきもの交渉史 (In Search of the Silk Road of the Sea: A History of East–West Exchange of Ceramics).

Misugi was most likely inspired by Japan’s attempts to re-engage with Eurasian countries after the Second World War, made evident in a fascinating ‘booklet’ compiled in English by a group of Japanese scholars in 1957. Produced for the first International Symposium for the History of East–West Cultural Contacts sponsored by the Japanese National Commission for UNESCO, the booklet outlined the state of Japanese scholarship on ‘East–West’ interactions. Noting that study of the topic, including the ‘treatment of Japan’ within that context, was ‘overshadowed by the strong emphasis on Chinese history’, the editors, Matsuda Hisao and Fujieda Akira, hoped that the ‘booklet might serve as a stimulus for discussion of the terms East–West as both directional terms and geographical terms’ (Japanese National Commission for UNESCO 1957: 4). The 154-page booklet, with contributions by some of the leading Japanese scholars of Asian history, is divided into six parts. After Matsuda’s ‘General Survey’ outlining the trends in Japanese scholarship on ‘East–West’ connections, the work is organized under the framework of ‘three lines of communication that connected the Asian continent from East to West—the Steppe Route, the Oasis Route and the Sea Route’. This is followed by thematic sections on ‘Western Cultural Influences in China’ and ‘Western Cultural Influences in Japan’. The booklet and the Symposium were organized as part of UNESCO’s ‘Major Project on the Mutual Appreciation of Eastern and Western Cultural Values’ (henceforth the ‘Major Project’) launched on 1 January 1957. Running until 31 December 1966, the decade-long project, which aimed ‘to promote contacts and understanding between peoples of the East and the West through better mutual appreciation of their respective cultural values’ (UNESCO 1968: 9), not only popularized the term ‘Silk Road(s)’ in Japan, it also laid the foundations for UNESCO’s ‘Integral Study of the Silk Roads: Roads of Dialogue’ project (henceforth the ‘Silk Roads Project’), initiated in 1988 and discussed in the next section.Footnote 10

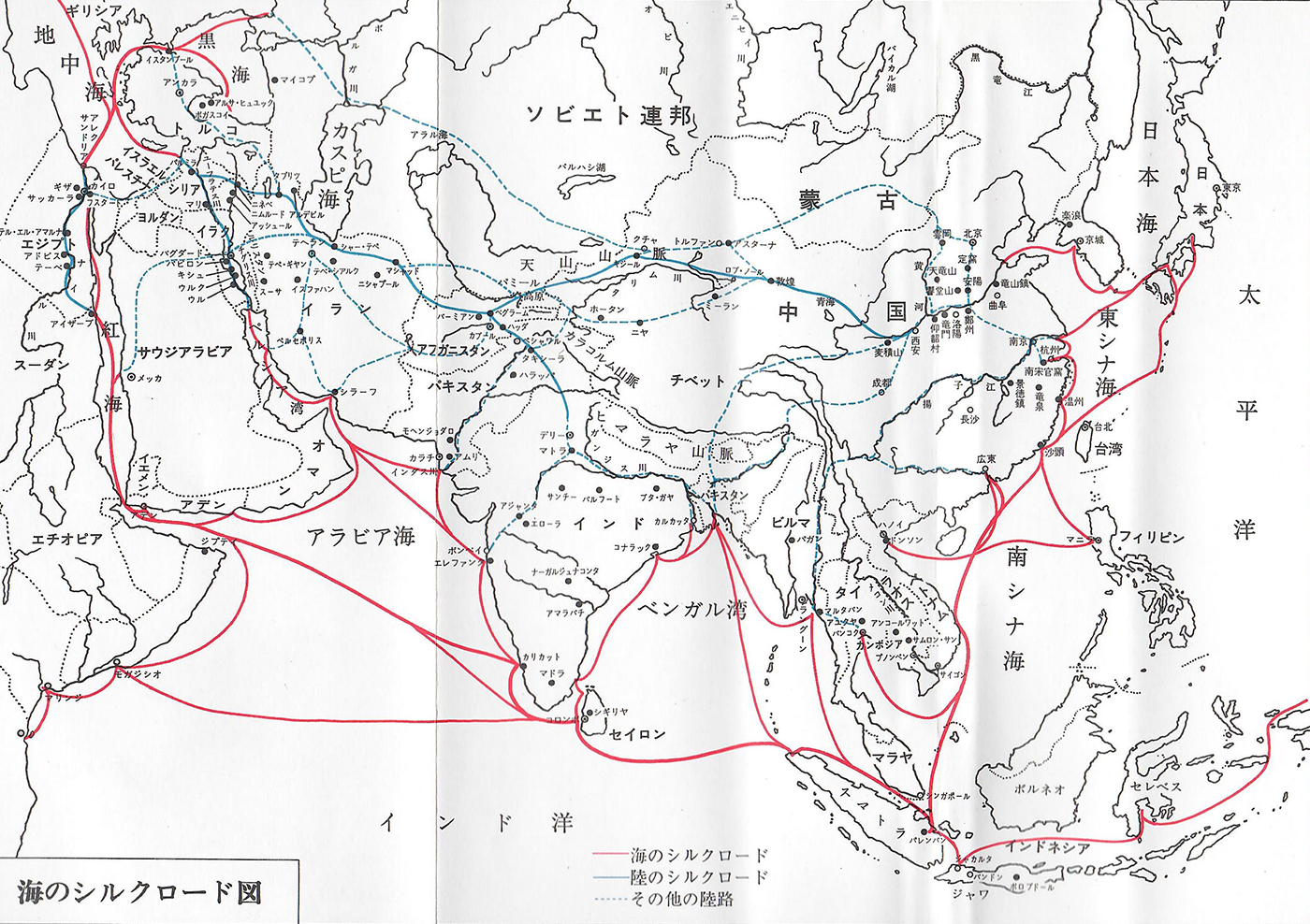

The impact of this venture to highlight ‘East–West’ connections and the increasing popularity of the term ‘Silk Road(s)’ in Japan are both reflected in the title of Misugi’s book, which contains both terms. According to Misugi, the book originated from his own ‘East-West’ travel in 1966, when he sailed to Istanbul. At the Topkapı Palace Museum in the Turkish city, he saw and became interested in Chinese ceramics from the Tang (618–907) and Song (960–1279) dynasties. This, Misugi (Reference Misugi1968: 6–8) explains, resulted in him undertaking research on the maritime trade between East and West using the ‘Silk Road of the Sea’Footnote 11 as a metaphor. In addition to describing the trade in ceramics, Misugi also examined the ships, religions, and people that traversed the Indian Ocean world. The book includes one of the first maps of the land and sea ‘Silk Roads’ (Figure 1). In the 1970s and 1980s, Misugi published several other books and articles on the topic. He was also involved in the Japanese media company NHK’s production of books and documentaries and participated in exhibitions highlighting Eurasian maritime connections.Footnote 12 Although most of his publications focused on ceramics, Misugi pointed out that silk and spices were also important commodities in these maritime commercial exchanges. Basing his research on Chinese textual materials and archaeological evidence, Misugi saw China as a key player in Indian Ocean interactions from the Qin dynasty (221–206 bce). This narrative also became dominant among scholars in the PRC, as seen from the quotation cited at the beginning of this article.

Figure 1. Map of the ‘Silk Roads’.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Chinese scholars in the PRC and elsewhere had yet to become aware of Misugi’s publications. While the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) prevented scholars from the PRC from accessing and engaging with Misugi’s ideas (Zhou 2014), others formulated their own concepts and terms. In an article published in 1974, the Hong Kong-based researcher Jao Tsung-I 饒宗頤 (Rao Zongyi, 1917–2018) coined the Chinese term Haidao de Silu 海道的絲路 (lit. ‘The Silk Road of the sea path’). While the article focused on the early interactions between China and India through Burma, the term appeared in the appendix discussing the export of silk by sea and the ships that are known as Kunlun bo 崑崙舶 in Chinese sources. Jao referenced Chavannes’ la voie de mer in arguing that during the mid-first millennium ce silk was exported by sea from Guangzhou to India and subsequently to Rome on these ‘Kunlun’ or Khmer ships (Jao Reference Jao1974: 582–583). Jao did not render Haidao de silu into English.

The current popularity and widespread use of the Chinese term Haishang Sichou zhi lu and its English rendition as the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ can be linked to several events that took place in the PRC during the 1980s. This included the ‘opening up’ of China’s coastal regions under the Special Economic Zones (SEZ) initiative established by Deng Xiaoping (1904–1997) in 1979, which resulted in a revived interest in the study of the history of Sino-foreign interaction (Zhongwai guanxi shi 中外關係史). Also important was the first major celebration of the Zheng He expeditions in 1985. By the end of the 1980s, augmented by the launch of the UNESCO Silk Roads Project in 1988, the idea of a Maritime Silk Road took hold in the PRC and around the world. An important figure in all of this was the PRC scholar Chen Yan 陳炎 (1916–2016).

A few years after the end of the Cultural Revolution, the PRC government acknowledged the mistakes of the ‘Anti-Rightist Campaign’ of the late 1950s, under which many intellectuals were removed from their academic positions and persecuted by the state. Chen Yan was one such person. A scholar of Burmese language and history, Chen had taught at Peking University since the establishment of the PRC in 1949. Branded a ‘Rightist’ in 1957 and then harassed during the Cultural Revolution, Chen was ‘rehabilitated’ and was eventually able to resume his academic career in 1979 at the age of 63.Footnote 13 A year later, he published an article proposing the idea of a ‘Southwest Silk Road’ (initially Xinan Sidao 西南絲道 and later Xinan Sichou zhi lu 西南絲綢之路) which connected the southwestern regions of the PRC (that is, the provinces of Sichuan and Yunnan) to India through Burma during the Han (206 bce–220 ce) and Tang dynasties (Chen Reference Chen1980). Chen argued that this ‘Southwest Silk Road’ was linked to the Central Asian ‘Silk Road’, as well as to the maritime routes that connected coastal China to West Asia. His article also carried a map depicting the routes through Central Asia, Burma, and across the Indian Ocean. In 1981, at the inaugural meeting of the newly established Association for Historians of China’s Foreign Relations (Zhongwai guanxi shi xuehui 中外關係史學會, later officially known as the Chinese Society for Historians of China’s Foreign Relations and by the acronym CSHCFR),Footnote 14 held in Xiamen, Chen became the first PRC scholar to propose the idea of a Haishang Sichou zhi lu. The Chinese and English versions of his presentation were published in 1982 and 1983 respectively (Chen Reference Chen1982, Reference Chen1983). The English translation, which appeared in the prestigious journal Social Sciences in China, published by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, was entitled ‘On the Maritime “Silk Road”’.

Chen Yan did not refer to the earlier writings of Misugi Takatoshi or Jao Tsung-I when he published his essays in the early 1980s. Rather, he drew ‘inspiration’ from his colleague at Peking University, the renowned Indologist Ji Xianlin 季羨林 (1911–2009). In 1955 Ji had published an article investigating the possibility of early Chinese silk entering India through Burma (Ji Reference Ji1955). Given Chen’s training in Burmese language and history, his interest in (re-)examining this possibility is understandable. It was during the course of writing about the ‘Southwest Silk Road’ that he also developed an interest in exploring the maritime spread of Chinese silk. In his publications on the ‘Maritime Silk Road’, Chen (Reference Chen1982, Reference Chen1983) argued that there was already an ‘eastern sea route of the Maritime “Silk Road”’ before the Common Era, through which silk was exported to Korea and Japan. Another branch, which Chen called ‘the South China Sea “Silk Road”’, facilitated the export and imperial gifting of silk to polities in Southeast, South, and West Asia prior to the seventh century ce. For him, the ‘developmental phase of the Maritime “Silk Road”’ took place during China’s Tang and Song dynasties, which coincided with an increase in the production, export, and consumption of silk in China and elsewhere. Concurrently, Chen argued, advances were made in Chinese shipbuilding and navigational techniques. The ‘Golden Age of the Maritime “Silk Road”’, according to him, came between the Yuan (1271–1368) and Qing periods, when silk was exported to the Americas through Manila.

Many of Chen’s arguments are highly problematic, as is his overall China-centric narrative. For instance, he claimed that ‘the export of Chinese silk helped people in these [foreign] areas to dress better’, that it ‘enriched and lent beauty to the life of [foreign] people’, that it also contributed to the creation of Chinese diasporic communities, and that it resulted in the formation of ‘a great communication artery connecting Asia, Africa, Europe and America’. He concluded that the export of silk by sea ‘exhibited a marvelous splendor in facilitating the exchange of ancient civilizations and had a huge impact on the cultures of various peoples of the world’ (Chen Reference Chen1983: 179). Despite such exaggerations, by the mid-1980s the idea of a China-centric ‘Maritime Silk Road’ started to have a wide-ranging impact on the intellectual community and policymakers in the PRC.Footnote 15 It became intertwined, for example, with the academic interest in the history of Sino-foreign interactions (see below), especially among the members of the CSHCFR and the Overseas Chinese History Society of China (Huaqiao lishi xuehui 華僑歷史學會), both organizations established in 1981. The celebrations marking the 580th anniversary of the Ming dynasty admiral Zheng He’s Indian Ocean expeditions in the PRC, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia in 1985 furthered these academic interests and more deeply entrenched the concept of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ in Chinese academia, popular literature, and the state’s propaganda agenda.Footnote 16

The preparations for the Zheng He celebrations started in 1983 with the establishment of an organizing committee under the direction of state leaders Bo Yibo 薄一波 (1908–2007), the vice-chairman of the Central Advisory Commission of the Chinese Communist Party, and Fang Yi 方毅 (1916–1997), then holding the position of state councillor. It was decided that the main event marking the anniversary would take place in Nanjing, ‘the second home’ of the Ming-dynasty mariner.Footnote 17 The renovation of archaeological sites associated with Zheng He, the establishment of memorial halls and research centres, the construction of an imagined (and often exaggerated) human replica of Zheng He, the production of publications on him and his expeditions, and a media blitz that included a TV series on the eunuch admiral were planned and completed by 1985 (Figure 2). The major commemorative meeting took place in Nanjing from 11 to 13 July and was attended by 3,000 people, including national, provincial, and city officials; military representatives; scholars; and delegates from various overseas Chinese communities. It concluded with a screening of a documentary entitled Haishang Sichou zhi lu 海上絲綢之路, especially produced for this occasion.Footnote 18

Figure 2. Calendar commemorating the 580th anniversary of the Zheng He expeditions.

As part of the Zheng He commemorations, the Chinese and English editions of China Pictorial (Zhongguo huabao 中國畫報) published a photographic essay on the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ based on interviews conducted in 16 countries situated around the Indian Ocean.Footnote 19 A comprehensive collection of these photographs, along with those related to the ‘Overland Silk Road’, appeared in China Pictorial (1989) (in separate English and Chinese editions) entitled The Silk Road on Land and Sea (Lushang yu Haishang Sichou zhi lu 陸上與海上絲綢之路). Chen Yan was one of the editors of these issues, which contained a detailed outline of his views on the ‘Southwest Silk Road’ and the ‘Maritime Silk Road’. Thus, by the end of the 1980s, the foundations of what could be termed a ‘Maritime Silk Road’ ecosystem and the related ‘invented tradition’ of China’s Indian Ocean heritage had been laid. This ecosystem involved academia, government officials, the media, and members of overseas Chinese communities. Its stakeholders claimed that 1) China had been the main driver of Indian Ocean interactions through its exports of silk; 2) China’s participation in Indian Ocean interactions dated back to as early as the second millennium bce; 3) the Zheng He expeditions were evidence of the friendly and harmonious intentions of Chinese engagement in the Indian Ocean; and 4) the connections between overseas Chinese communities and their ancestral homeland had been an essential part of these maritime connections.

There was another important facet to this ecosystem in the 1980s, one that involved linking the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ to the PRC’s ‘open-door’ policy. This concept was employed as a metaphor by some Chinese intellectuals and officials in order to endorse the economic reforms instituted in 1979 and express support for the PRC’s renewed engagement with the outside world. This became evident during the celebrations marking the 580th anniversary of Zheng He’s expeditions. Speeches delivered by scholars and officials made reference to Deng Xiaoping’s ‘open-door’ policy, the ‘indomitable pioneering spirit of the Chinese people’ (Zhonghua minzu dawuwei de kaituo jingshen 中華民族大無畏的開拓精神), and the ‘patriotic education’ (aiguo jiaoyu 愛國教育) that outlined Chinese navigational achievements and could ‘help build a socialist spiritual civilization in China’ (zhuyu woguo shehui zhuyi jingshen wenming de jianshe 助於我國社會主義精神文明的建設) (Zhongguo hanghai xuehui 1986). Three years later, in 1988, a journal article argued that the establishment of the SEZs was similar to the ‘opening’ of the historical ‘Maritime Silk Road’ and was capable of strengthening the economies of the hinterland areas and the coastal regions of the PRC (Wu Reference Wu1988). That same year, the People’s Daily published a commentary introducing a book on contemporary economic relations between China and Southeast Asian countries that invoked the idea of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ to describe the regions’ ‘long history of trading relations’ (Liu Reference Liu1988). Another commentary suggested that connecting the hinterland areas and coastal regions through railway networks could result in the ‘formation of multiple twentieth-century maritime and overland “Silk Roads”’ (Ji and Yang Reference Ji1988: 5).

The invoking of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ as a metaphor to endorse economic reforms and the ‘open-door’ policy was most likely related to the debates and the political tensions within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The six-part China Central Television (CCTV) documentary called Heshang 河殤 (River Elegy) became a controversial part of this debate by highlighting the superiority of an outward-looking oceanic civilization over the traditional inward-looking Chinese civilization based in the Yellow River (Lau and Lo Reference Lau and Yuet-keung1991; Ma Reference Shu-Yun1996). First screened in June 1988, the documentary triggered debate and discussion among Chinese politicians, intellectuals, and students about the pace, extent, and impact of the ‘open-door’ policy. It was banned after a few months because it had allegedly disparaged traditional Chinese culture, especially Confucianism, as well as presenting a ‘critical reflection’ on China’s recent (post-1949) past.Footnote 20 Its banning, followed by the crackdown on the student movement in 1989, resulted in a temporary halt to the process of linking the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ idea to the state’s economic and ‘open-door’ policies, at least until Deng Xiaoping’s ‘southern tour’ in early 1992, which reconfirmed the PRC’s commitment to economic reforms. Instead, the focus shifted to the heritagization of China’s maritime past. The main reason for this shift was UNESCO’s Silk Roads Project, which, despite the concerns over human rights issues related to the Tiananmen crackdown, swiftly integrated the PRC into the Eurasian project. This also paved the way for the PRC to assert exclusivity over, claim cultural ownership of, and ultimately promote the concept of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ as ‘China’s Maritime Silk Road’ globally.

International platform, national pride

Just as the ideas about the ‘Maritime Silk Road’, its role in the construction of a maritime heritage, and its use in the contemporaneous discourse on the ‘open-door’ policy were coalescing in the late 1980s PRC, UNESCO launched its own Silk Roads Project. It is argued in this section of the article that the converging of these two streams between 1988 and 1998 contributed to the worldwide recognition of the term ‘Maritime Silk Road’. At the same time, however, the encounter with foreign academia seems to have kindled nationalist sentiments within the PRC, especially among those trying to use the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ narrative to promote the case for China’s central role in Indian Ocean interactions. Many of these people were members of CSHCFR, which played a significant role in the writing of the history of China’s interactions with foreign regions using the framework of the ‘Silk Roads’. These developments in the 1990s and the discourse on the ‘Maritime Silk Road’, extending through to the Beijing Olympics in 2008, were all crucial for the invention of a storyline about China-driven Eurasian overland and maritime connections that is now a key feature of the BRI propaganda. This storyline is disseminated through various means and media, including, as discussed later in the article, international exhibitions and performances.

Vadime Elisseeff, the chairman of UNESCO’s International Consultative Committee of the Silk Roads, which oversaw the Silk Roads Project, credited the Major Project of 1957–1966 with serving as a ‘guide’ to the organization’s new initiative.Footnote 21 From that earlier undertaking, Elisseeff (Reference Elisseeff and Elisseeff2000: 13) explained, ‘emerged the notion of three intercultural routes: the Steppe Route, the Oasis Route, and the Maritime Route’. Like the Major Project, the Silk Roads Project also stressed ‘academic credibility’ and the dissemination of the project’s findings to general audiences as its two main objectives. Thus, academic conferences, exhibitions, publications, and media coverage became the main elements of what was highlighted as ‘the avant-garde of a new type of Unesco project, the “projets mobilisateurs” mobilisation projects’ (UNESCO 1988: 1). By the time the project concluded in 1998, the ‘Silk Roads’ had achieved worldwide recognition.

At the beginning of this new UNESCO project, however, there was ambiguity over the term ‘Silk Roads’ and the methodology for studying it. For example, the ‘Final Report of the Meeting of the Consultative Committee’ of the Silk Roads Project, dated 9–11 May 1988, pointed out that ‘the term “Silk Roads” must be defined’. There was also a call at the meeting to design a methodology that would provide a ‘firm framework for research’. Additionally, the Committee emphasized the need for a ‘careful sifting and verifying of primary sources’ (UNESCO 1988: 3). Other details about the early deliberations and the project’s objectives appeared in the inaugural issue of the Silk Roads Project newsletter, published in 1989. The newsletter (UNESCO 1989: 2) noted that the project, conceived initially as a five-year scheme, aimed to ‘make people living in the present day aware of the need for a renewed dialogue among themselves, and to help them discover the historical records of human understanding and communication which provided a mutual enrichment for different civilizations along these roads’. It also set out the project’s research and dissemination plans. While ‘a series of interdisciplinary seminars, as well as meetings with local specialists’ were highlighted as ways to ‘make significant contributions to contemporary scholarly research and cultural reflection’, the proposal for three expeditions ‘along the main Silk Roads’ was intended to satisfy the project’s ‘popular’ dimension. These expeditions, the newsletter (UNESCO 1989: 2) explained, would ‘provide the opportunity to produce documentary films, publications and exhibitions’. The first of these expeditions, along the ‘Desert Route’, began from Xi’an on 20 July 1990; the ‘Maritime Route Expedition’ commenced from Venice on 23 October 1990; and the ‘Steppe Road Expedition’ started from the Turkmenistan capital Ashgabat on 19 April 1991.

The idea of focusing on the maritime route was introduced during preliminary deliberations on the Silk Roads Project by Bal Krishen Thapar, India’s UNESCO representative to the Consultative Committee. Thapar, an archaeologist, had previously served as director-general of the Archaeological Survey of India. At the Consultative Committee meeting on 10 May 1988, Thapar emphasized the ‘need to differentiate between the coastal route and the high seas route’. As part of the maritime aspect of the Silk Roads Project, he argued that ‘changes in the environment require study, as do advances in the technology of ship-building, astronomy, etc.’. Thapar also stressed ‘the parallel importance of archaeological investigation and the study of literary sources’, as well as the ‘need for close cooperation with those planning the land routes’ (UNESCO 1988: 5). He was appointed the coordinator for the ‘Maritime Route’ sub-committee. At the same meeting of the Consultative Committee, Oman’s representative offered a ship called the Fulk al-Salamah (‘Ship of Peace’) on behalf of his government to those coordinating the project’s maritime route (UNESCO 1988: 5).Footnote 22 The Chinese delegates, who noted the ‘absence’ of specialists from the PRC at the meeting, seem only to have reviewed the proposed ‘Desert Route’ expedition. In fact, reports from the initial Consultative Committee and the various sub-committee meetings on the project do not indicate that the Chinese side proposed any academic symposia, research projects, or media coverage on the maritime route at the meeting. It is conceivable that, while the Chinese delegates were easily able to identify the importance of Xi’an and discuss the ‘Desert Route’ because of the existing popularity of the ‘Overland Silk Road’ in the PRC, they had no clear knowledge of recent writings on the ‘Maritime Silk Road’.

Almost a year later, in March 1989, Jia Xueqian 賈學謙 (1921–), the deputy secretary-general of the Chinese National Commission for UNESCO, first visited Quanzhou and encountered the concept of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’. Most likely during his interactions with Wang Lianmao 王連茂 (1941–), the director of the Quanzhou Maritime Museum, Jia was told that Quanzhou was internationally recognized as the ‘starting point’ (qidian 起點) of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ and that it was also an important qiaoxiang 僑鄉 city (that is, the hometown of many overseas Chinese), with its diasporic networks extending to over 90 countries, including about eight million people living in Taiwan (Jia Reference Jia2004: 133–134).Footnote 23 At a meeting with city and provincial officials, Jia (Reference Jia2004: 134) remarked that it would be a ‘great disappointment if the international expeditionary research team for the Maritime Route of the Silk Roads did not come to Quanzhou’, as this, he argued, would render ‘the research [on the route] incomplete’. Jia’s visit resulted in the greater involvement of the PRC in the Maritime Route Expedition and Quanzhou’s emergence as the main host for the UNESCO delegation.

Shortly after the UNESCO Consultative Committee meeting in Xi’an in late April 1989, representatives from the Chinese National Commission for UNESCO, the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Finance, the Academy of Social Sciences, and other key governmental organizations discussed the Silk Roads Project and jointly asked the State Council to formally approve the PRC’s participation in order to ‘uphold sovereign rights, be an active participant, strengthen cooperation, [and] expand the influence of the PRC, while acting within financial means’ (Jia Reference Jia2004: 5–6). The State Council’s approval led to the establishment of the China Silk Roads Project Coordination Group (Zhongguo Sichou zhi lu xiangmu xietiaozu 中國絲綢之路項目協調組) under the leadership of Jia Xueqian. Jia returned to Quanzhou in November 1989 to participate in a planning meeting for the conference associated with the Maritime Route Expedition. The China Silk Roads Project Coordination Group met in Beijing a month later to finalize the logistical details and coordination plans with various coastal provinces and cities (Jia Reference Jia2004: 5–6). These meetings, the local engagement with UNESCO’s Silk Roads Project, and the publicity Quanzhou received through its participation sparked strong interest among coastal cities in the PRC in integrating themselves into the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ discourse and pursuing, as detailed in the next section, its inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

UNESCO’s Maritime Route Expedition started out from Venice after an international seminar on ‘Travel Literature or Travels of Literature’. The Fulk al-Salamah set sail on 23 October 1990 flying the flag of the United Nations and ‘accompanied by a flotilla of historical boats and heralded by a fanfare of trumpets’. The ship stopped at 21 ports in 16 countries before finally reaching Osaka on 8 March 1991. Various cultural programmes, academic conferences, and field visits were organized at each of these ports, while on board the ship, slide and video presentations, lectures, and ‘brainstorming’ sessions were held. ‘On a rotating basis’, 90 scholars from 26 countries formed the ‘international team’ leading this maritime expedition (UNESCO 1991: 2). Many more scholars attended onsite academic conferences, including Misugi Takatoshi, who participated in the conference held in Brunei’s capital Bandar Seri Begawan, and Chen Yan, who did the same in the Philippines and Quanzhou.

Liu Yingsheng 劉迎勝 (1947–), a Nanjing-based historian of the Mongols who had thus far not published on Indian Ocean interactions, represented the PRC on the Maritime Route Expedition.Footnote 24 Liu’s 1992 report on the expedition provides important details about the onsite academic conferences and the deliberations that took place on board the Fulk al-Salamah. Liu (Reference Liu1992: 109–110) acknowledged the impact of UNESCO’s project on ‘Silk Roads’ studies in China by noting that it had ‘strengthened national confidence’ (zengqiang minzu zixinxin 增強民族自信心), ‘expanded academic horizons’ (kaikuo xueshu shiye 開闊學術視野), and contributed to the ‘cultivation of a new generation of scholars’ (peiyang xinyidai xuezhe 培養新一代學者). Liu’s report is especially noteworthy because it indicates how Chinese views on the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ started to be internationalized through the UNESCO Silk Roads Project. When, for instance, the representative of Oman argued that Chinese ships had not travelled to the Persian Gulf before the Mongol Yuan period, Liu (Reference Liu1992: 102–103) countered that such ‘Chinese ocean-going boats’ did in fact ferry passengers from China ‘sailing directly’ (zhihang 直航) to the Persian Gulf as early as the middle of the eighth century ce. Later, at a conference held in Sri Lanka where B. E. S. J. Bastiampillai of the University of Columbo interpreted Zheng He’s expeditions in terms of Ming China’s military expansion into the Indian Ocean region and demonstrated its exploitative trade relations with Sri Lanka, Liu (Reference Liu1992: 104) argued that the expeditions were the ‘most glorious maritime activities of the Asian people before the arrival of the Western colonizers’. Liu also maintained the primacy of Chinese historical records over those from Sri Lanka, which he noted were composed much later.Footnote 25

This nationalistic framing of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ idea and China’s exclusivity over it became more prevalent in the PRC during the 1990s, including in the new writings of Chen Yan. In 1991, Chen Yan participated in an onsite conference in Quanzhou organized as part of the Maritime Route Expedition, where he reiterated his views on China’s important contributions to ‘world civilization’ (shijie wenming 世界文明) through the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ (Chen Reference Chen1991: 4–5). Shortly thereafter, in 1996, when he published a collection of his articles on the ‘Maritime Silk Road’, Chen acknowledged Misugi’s works for the first time. In the preface to the collection, Chen noted that he had come to know of Misugi’s publications, but because of the ‘Anti-Rightist’ movement he had no way of accessing his writings. Chen then explained that ‘I felt deeply that this research [on the “Maritime Silk Road”] should be taken up urgently by Chinese scholars because it is part of the glorious history of the Chinese nation. The Chinese people certainly have the right to articulate [on the topic], and, therefore, it ought to be written about by the Chinese’ (Chen Reference Chen1996: vii). Alluding to Misugi’s contributions, Chen remarked that the Chinese had been ridiculed by some Japanese scholars, arguing that ‘[historical] sources were located in China, but research took place in Japan’. This, according to Chen, implied that ‘China had the [primary] sources but lacked the skills to research them, for which Chinese scholars had to depend on the Japanese’. He urged Chinese academics not to fall behind foreign scholars, emphasizing that, since the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ originated in China, it was their research and writing that would ‘enhance the glorious history of our Chinese people’ (Chen Reference Chen1996: viii).

Chen elaborated on this latter point by describing his experience of participating in UNESCO’s Silk Roads Project, which made him realize the international significance of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’. The implication of this, he wrote,

is especially significant for our China. At every international symposium, whenever there is a discussion of the ‘Maritime Silk Road,’ virtually every paper touches upon the impact of Chinese culture on the political, economic, commercial, cultural, ethnic, religious, and other aspects of countries through which the road passed. The history of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ is an inseparable part of the history of the Chinese nation. The ‘Maritime Silk Road’ not only connected East and West through trade and friendly exchanges, and furthered the friendship and understanding between different peoples, but also gave an impetus to the economic and cultural exchanges between East and West, and wrote a glorious page in the development of world civilization. (Chen Reference Chen1996: xi)

Liu’s and Chen’s nationalist framings of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ follow a pattern of using history for nation-making purposes that has been prevalent in China from the early twentieth century. While Prasenjit Duara (Reference Duara1995) has demonstrated this practice in the case of Chinese historiography of China, Xin Fan (Reference Fan2021) does so for Chinese historiography of world history. Starting with Liang Qichao, Duara (Reference Duara1995: 33–34) explains that ‘much of the Chinese intelligentsia rapidly developed a linear, progressive history of China that was modelled in the European experience of liberation from medieval/autocratic domination’. Duara (Reference Duara1995: 35–36) also points out that Liang’s ‘politics of “great nationalism” obliged him to incorporate the non-Han into the nation’ by establishing a threefold linear periodization of Chinese history that highlighted China’s encounters with other Asians during the ‘ancient’, ‘medieval’, and ‘modern’ periods.

It was in this context of laying the foundations for Chinese historiography that Liang resurrected Zheng He, a Muslim and a eunuch, and transformed the Ming admiral into a national hero and a key figure in later discourse on the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ idea. Indeed, the ‘invented tradition’ of China’s Indian Ocean heritage through the ‘choosing’ of Zheng He started with an essay of Liang’s that appeared in the 1904 issue of Xinmin congbao 新民叢報 (New People’s Miscellany).Footnote 26 Liang compared Zheng He to Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, and Ferdinand Magellan to highlight the superiority of the Ming ships and the admiration the people and states in the Indian Ocean had for Zheng He, for his ‘bravery’ and contribution to quelling local ‘rebellions’. Moreover, Liang claimed that the territories in various parts of Southeast Asia were ‘our lands abroad’ because of the Ming expeditions and the ensuing migration and economic contribution of the Chinese people to the region. As Liang (Reference Liang1904: 26) wrote,

A large part of Southeast Asia, so-called Indochina and the Nanyang Archipelago, are the places where the Chinese nation extends into the ocean [lit. ‘are the geographical nadir of the Chinese nation’]. In the future it will again be exclusively part of the Chinese nation’s sphere of influence. Speaking about the present situation [there], the white people are in control of its politics on the surface [lit. ‘treat its people like corpses’], yet their ability to run the local commerce is no match for ours.

Liang suggests that in the future Chinese migrants will be able to bring the regions into the ‘Chinese nation’s sphere of influence’, and he gives figures for such people already in the various colonial regions of Southeast Asia. As with the widespread acceptance of his historiography of China in the PRC, Liang’s portrayal of Zheng He became the prevalent framework for Chinese writings on the Ming’s maritime expeditions, including those by Liu Yingsheng and Chen Yan, and, with the emphasis on the Chinese overseas communities, became core elements of the ‘China’s Maritime Silk Road’ narrative.

Xin Fan has pointed to a similar nationalist trend in Chinese scholarship on world history. ‘The writing of the ancient past,’ he points out, ‘was not merely an intellectual practice; it was also a way for Confucian scholars to participate in contemporaneous politics’ (Fan Reference Fan2021: 19). He argues that the CCP state introduced historical materialism and attempted to turn world history into the ‘handmaiden of political ideology’ (Fan Reference Fan2021: 89–90). In the early 1980s the field was called on to ‘serve China’s Four Modernizations movement’. After the founding of the PRC, the national history of China was separated from the study of world history, essentially creating two separate fields in historical studies. In the 1990s, Xin Fan (Reference Fan2021: 154) explains, China’s world historians abandoned their use of a Marxist framework, which had thus far dominated historiographical analyses in the PRC, to ‘give way to their nationalist emotions’. These scholars with ‘nationalist emotions’ believed that ‘world history in China should be written in a “Chinese” way’. This led to ‘deep tensions between local and global identities that confront many Chinese scholars, as they face the pressure to maintain a nationalistic standpoint, while engaging in a subject whose content is considered to be not “Chinese”’ (Fan Reference Fan2021: 196). Chinese scholars of the ‘Silk Roads’ addressed this ‘tension’ by integrating themselves into the field of the history of Sino-foreign interactions, which became popular in the PRC during the 1980s and 1990s. This field bridged the gulf between national (that is, Chinese) and world histories by placing China at the centre of transnational research and publications. The ‘Silk Roads’ framework also provided scholars in this field of study with an opportunity to ‘reinforce’ the ‘invented tradition’ of Chinese maritime history and heritage.

Zhang Xinglang 張星烺 (1888–1951), Feng Chengjun 馮承鈞 (1887–1946), Chen Yuan 陳坦 (1880–1971), and Xiang Da 向達 (1900–1966) were four pioneers in this field of research.Footnote 27 During the first half of the twentieth century, they contributed to the compilation of textual sources on China’s historical interactions with foreign lands and the translation of foreign writings on the topic. During the 1950s, scholars such as Zhou Yiliang 周一良(1913–2001) and Jin Kemu 金克木 (1912–2000) wrote books on these interactions as part of the PRC’s agenda to promote ‘friendship’ with foreign countries.Footnote 28 The most comprehensive research on the topic was undertaken by Fang Hao 方豪 (1910–1980), whose five-volume study entitled Zhong-Xi jiaotong shi 中西交通史 (History of the Intercourse between China and the West) was published in Taiwan in 1953. Fang acknowledged the emphasis on China in his study by explaining that the fields of the ‘History of Eurasian Intercourse’ (Ou-Ya jiaotong shi 歐亞交通史) and ‘History of East–West Intercourse’ (Dong-Xi jiaotong shi 東西交通史) also concentrated on China. According to Fang (1968 [Reference Fang1953]: 3–28), the study of China’s interactions with the ‘West’ developed through five avenues: 1) research on China’s northwestern regions by Chinese scholars, which he saw as beginning during the Jiaqing period 嘉慶 (1760–1820), led by Qing scholars belonging to the kaozheng 考證 (‘evidential’) school; 2) exploration of the geography of foreign regions by Chinese scholars, which started with the Qing’s interest in the history of the Mongol Yuan dynasty; 3) studies of China by European and American scholars under the rubrics of ‘Orientology’ (Dongfang xue 東方學) and ‘Sinology’ (Hanxue 漢學), which began with their focus on ‘East–West’ interactions during the Mongol Yuan dynasty; 4) the examination of China by Japanese scholars, especially those interested in the ‘comprehensive history of China’ (Zhina tongshi 支那通史); and 5) the archaeology of Central Asia and Dunhuang, studies that began with the exploration of Chinese Central Asian sites in the early twentieth century by Europeans such as the Swedish geographer Sven Hedin (1865–1952) and the British archaeologist Aurel Stein (1862–1943).

Fang Hao’s work and his conceptualization of the field were still unknown to PRC scholars when the CSHCFR was established in May 1981 in Xiamen. A report detailing the founding of the CSHCFR in its inaugural newsletter (tongxun 通訊) pointed out that the field engaged with both Chinese and world histories, and that it would not limit itself to the issue of political relations, but would also focus on prehistoric cultural interactions between China and foreign regions, including the movement and migration of people into and out of China (Anonymous1 1981: 1–4). The study of the history of Sino-foreign interactions, the report emphasized, did not represent a contemporary foreign-policy agenda, nor were scholars in the field ‘spokespeople of the foreign ministry’. It added that the state’s diplomatic organizations should not ‘assign political responsibilities to academic writings. Only in this way will research on the history of Sino-foreign interactions genuinely develop, and only then will this academic field be able to truly serve foreign diplomacy’ (Anonymous1 1981: 2). Despite this desire to detach academic research from the state’s foreign policy and diplomatic agenda, the CSHCFR’s mission included contributing to ‘the realization of the Four Modernizations [policy] for the motherland’. In fact, the relevance of the field to the nation, its policies, and national pride were regularly emphasized at the CSHCFR’s conferences and in its publications.

The 1983 newsletter of the CSHCFR published a speech by the famous world historian Zhu Jieqin 朱杰勤 (1933–).Footnote 29 Citing Deng Liqun 鄧力群 (1915–2015), then the CCP’s propaganda chief, who earlier that year had urged historians to promote patriotic education among the Chinese through research, instruction, and publications, Zhu described China’s many contributions to foreign societies in the past. These contributions, he noted, were evident in the research and publications on the history of Sino-foreign interactions. Zhu opined that past exchanges could serve as a model for contemporary foreign relations, and research on the topic could assist in building the ‘Four Modernizations’ and the ‘rejuvenation of China’ (zhenxing Zhonghua 振興中華) (Zhu Reference Zhu1983: 3–4).

Support for the ‘Four Modernizations’ and the ‘open-door’ policy by members of the CSHCFR featured more prominently in its third academic conference, held in August 1988 at Beidaihe with the theme ‘Open- or Closed-[Door] Policies During the Ming and Qing Period and Their Impact on the Development of Society’. In his opening remarks, Han Zhenhua 韓振華 (1921–1993), then the CSHCFR’s president, pointed out that discussion on the historical theme at the conference had ‘real meaning’ for the contemporary policies of ‘opening up’ to the outside world and the revitalization of the domestic economy. Several presenters at the conference argued that the limits placed on foreign trade during the Ming and Qing periods, or its outright banning, were among the main reasons for China’s backwardness.Footnote 30 It is not clear if this vocal support for ‘opening up’ or the sympathies that some members, including Ji Xianlin, expressed for the student protests in Tiananmen Square had any impact on the CSHCFR’s functioning, but the organization did not mark its tenth anniversary in 1991, nor did it publish its newsletter in 1990 or 1991. In 1992, at its academic conference held in Yangzhou, the CSHCFR passed an updated version of its statutes that reconfirmed the organization’s commitment to the ‘Four Modernizations’. Its statutes also included a requirement that its members should have a ‘patriotic spirit’ and ‘uphold the Four Basic Principles’. Furthermore, the CSHCFR formally added the word Zhongguo (China/Chinese) to its official name, the English rendition being ‘Chinese Association of the Historians of Relations between China and Foreign Countries’ (Anonymous2 1992: 8–10), which was eventually changed to the CSHCFR in 1999.

The nationalist views expressed by Liu Yingsheng and Chen Yan, the assertion of Chinese exclusivity over the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ narrative, and the tensions between PRC and foreign scholars should be understood in this context of the development of the field of the history of Sino-foreign interactions. In fact, Chen Yan participated in the inaugural meeting of the CSHCFR, where he first presented his views on the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ and later served as a permanent member of its executive council. ‘Silk Roads’ studies, which extended to coverage of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’,Footnote 31 was from the outset an important focus of the CSHCFR’s conferences and publications. This emphasis was highlighted in 2001, when the CSHCFR marked its twentieth anniversary and held its fifth academic conference in Kunming, Yunnan. The theme of the conference was ‘Comparative Research on the Southwest, Northwest, and Maritime Silk Roads’. Geng Sheng 耿昇 (1945–2018), the then president of the CSHCFR, pointed out that 2001 had been declared the ‘Year of the Silk Roads’ 絲綢之路年 by Chinese academics (Geng Reference Sheng2005: 18–19). He explained that this was the first time that the three ‘Silk Roads’ had been discussed together in an academic forum in the PRC, leading to scholars referring to the conference as the ‘Three Silk [Roads] Stir Fry’ (chao san Si 炒三絲) because of the multiple disciplinary and research perspectives presented at it.

The fact that Chinese scholars perceived the three ‘Silk Roads’ as distinct and unique routes of communications was apparent in the papers presented at this conference. Some of them directly addressed the problems with the ‘Silk Roads’ narrative that had taken root in the PRC. These included the question of whether every route through which China’s interactions with foreign regions took place should be designated a ‘Silk Road’, and whether the routes where silk was not the primary commodity of exchange should be described as a ‘Silk Road’ for propaganda purposes. The Yunnan-based scholar Yao Jide 姚繼德 pointed out that the term ‘Silk Road(s)’ no longer referred to the trade in silk but had rather come to be used as a metaphor for the ‘communication networks’ between China and foreign countries (Geng Reference Sheng2005: 20). Another Yunnan-based scholar, Ma Yong 馬勇, specifically questioned the narrative of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ in his paper entitled ‘Southeast Asia and Maritime Silk Road’. Ma argued that studies of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ had emphasized the Sinocentric view at the cost of neglecting other regions of the maritime world, especially Southeast Asia and its role in marketing and consuming various commodities (Geng Reference Sheng2005: 29).Footnote 32

However, the celebrations marking the 600th anniversary of Zheng He’s expeditions in 2005, followed by the Beijing Olympics in 2008, integrated the terms ‘Silk Roads’ and ‘Maritime Silk Road’ into Chinese ‘national emotions’, national pride, and academia more deeply. The issues raised at the 2001 conference of the CSHCFR went unanswered. Rather, the CSHCFR started to use the ‘Silk Roads’ theme more frequently for its conferences to signify all forms and periods of exchanges between China and foreign regions. While it is possible that the ‘Silk Roads’ umbrella initially served the practical purpose of bringing together the diverse research on the history of Sino-foreign interactions in the PRC, from 2013 onwards it became clear that the objective was to endorse and become part of the BRI project by affirming the narrative of China-centric overland and maritime interactions propagated by the state. The latter agenda was conspicuous during the CSHCFR’s meeting in 2017, which was entitled ‘Historical Changes in the Maritime and Overland Silk Roads and Contemporary Inspiration’. In the foreword to the collection of conference papers published in 2020, the CSHCFR’s president Wan Ming 萬明 (Reference Wan and Ming2020: 1–3) invoked Xi Jinping’s BRI ‘national initiative’ (guojia changyi 國家倡議) and interspersed her essay with several government slogans, such as ‘community of shared interest’ (liyi gongtongti 利益共同體), ‘community of shared destiny [for mankind]’ ([renlei] mingyun gongtongti [人類]命運共同體), ‘going global’ (zou chuqu 走出去), and ‘telling the China story well’ (jianghao Zhongguo de gushi 講好中國的故事). Wan Ming called upon the CSHCFR’s members to promote the PRC’s ‘soft power’ (ruan shili 軟實力) with research on the ‘Silk Roads’. Specifically with regard to the ‘Maritime Silk Road’, she wrote:

The current construction of the ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ is premised on the nation’s need for historical and cultural soft power support, consolidates the nation’s rich cultural heritage, and inherits and celebrates its commitment to peaceful interactions and cooperation, values underpinning the ancient Silk Roads. It has imbued the Silk Roads of yesteryear with completely new meanings reflective of this moment in history: Animated by the Silk Road ideals of peace and cooperation, openness and inclusiveness, and mutual learning and mutual benefit, this project aims to forge a ‘community of shared interest’ in which all countries along the Silk Roads benefit and a ‘community of shared destiny’ in which development and prosperity are achieved by every participating country. (Wan Reference Wan and Ming2020: 2)

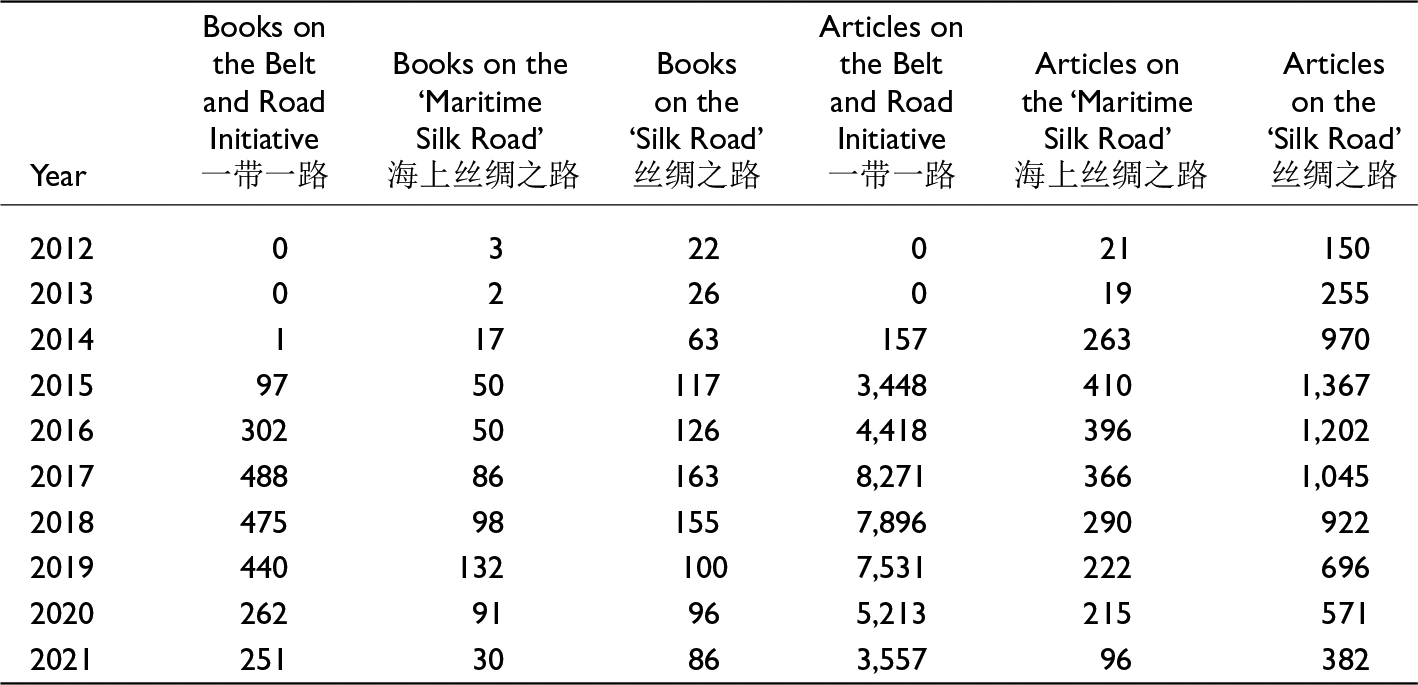

The final sentence of Wan Ming’s explanation of the contemporary connotations of the ‘Silk Roads’ idea matches almost word-for-word the content of the former Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s 王毅 (1953–) 2018 speech delivered at the opening of the ‘Forum on Belt and Road Legal Cooperation’ at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse.Footnote 33 In fact, the parroting of such passages has become common in recent academic publications on the ‘Silk Roads’ in the PRC, which, as Table 1 below indicates, increased significantly, reflecting how ‘Silk Roads’ studies and, more broadly, the field of the history of Sino-foreign interactions have been institutionalized to serve the national agenda.Footnote 34 More importantly, the field has now been incorporated into what Prasenjit Duara (Reference Duara2003) has called a ‘regime of authenticity’ (see below), which coastal cities and provinces are using to legitimize their ‘Maritime Silk Road’ heritage, and that the nation-state is exploiting in order to claim territorial sovereignty over the South China Sea region. The next two sections examine these applications of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ in the PRC.

Table 1: Chinese-language publications on the BRI, ‘Maritime Silk Road’, and ‘Silk Road’.

Sources: Duxiu 讀秀 for books, and CNKI for articles. Data as of February 2023.

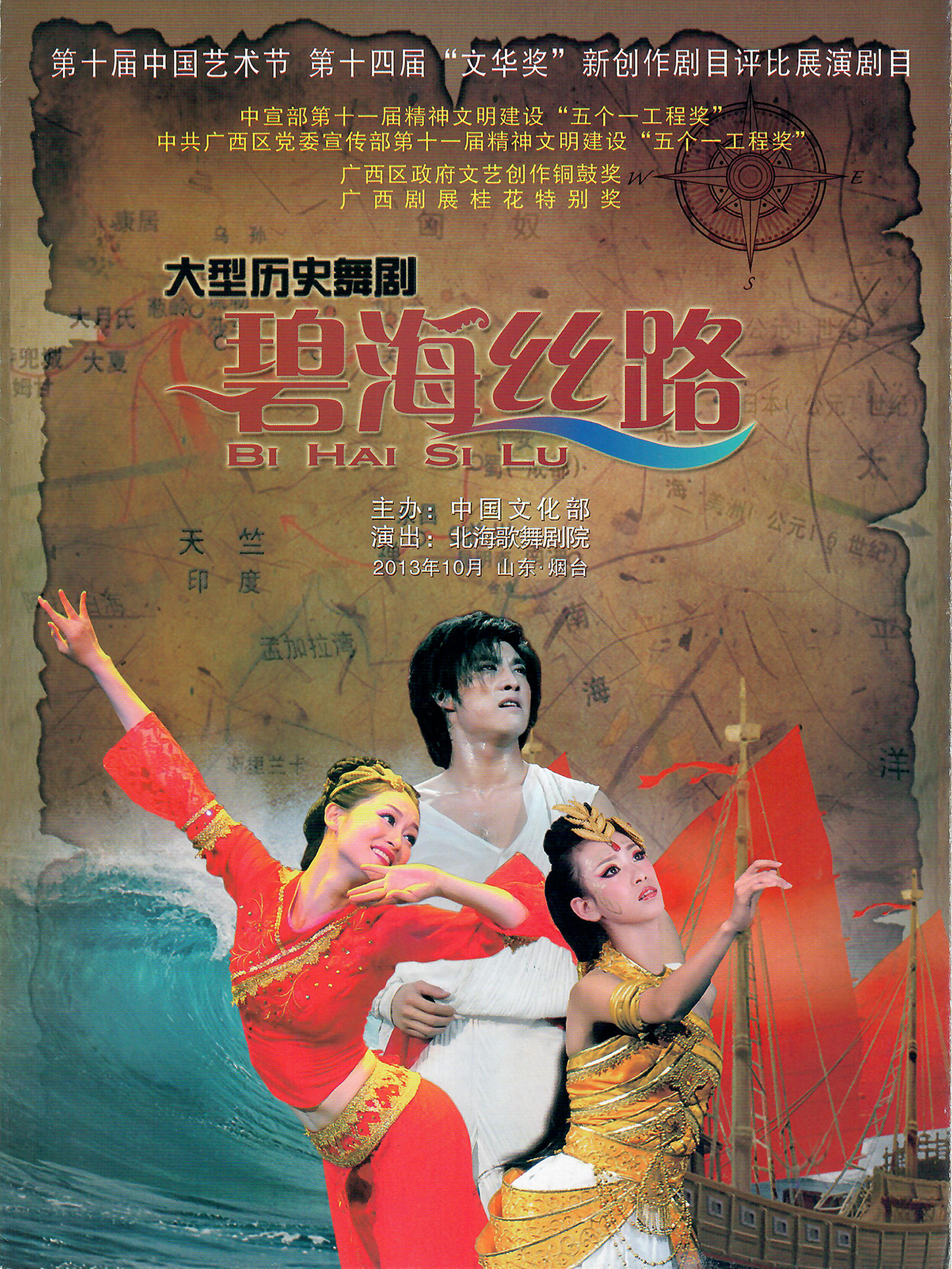

The messiness of heritagization

The final two sections of this article examine the incorporation of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ discourse into the agendas of local and national governments in the PRC. At the local level, as this section illustrates, the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ concept was invoked by several coastal cities to compete for UNESCO World Heritage listing, while at the national level, the next section shows, it was used to promote a harmonious image of the PRC through international exhibitions and performances at the same time as asserting territorial claims in the South China Sea region. This absorption, and the associated promotion and propaganda schemes, resulted in the expansion of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ ecosystem and augmented the China-centric embodiment of the term.

Claims for UNESCO World Heritage listing and to contested territories both require ‘authentication’ of the past. In both cases, too, national pride plays an important role. ‘Bringing a site onto the World Heritage List,’ as Christoph Brumann (Reference Brumann, Schnepel and Sen2019: 21) points out, ‘often boosts tourism, national and local pride, as well as the flow of investments and development funds.’ The PRC is no exception to this, as instilling a ‘strong sense of nationalism and patriotism’ and enhancing domestic and foreign tourism are key factors driving its pursuit of World Heritage inscriptions (Zhang Reference Zhang2020: 57–58).Footnote 35 Asserting sovereign rights over disputed territories likewise nurtures national pride in the PRC, where such claims are closely associated with the ‘national humiliation’ discourse (Callahan Reference Callahan2012; Wang Reference Wang2012). Duara (Reference Duara2003: 25–26) describes the ‘regime of authenticity’ as a ‘regime of symbolic power capable of preempting challenges to the nation-state or nationalists by proleptically positing or symbolizing the sacred nation’. He continues: ‘This regime does not simply possess a negative or repressive power. It also allows its custodians to shape identities and regulate access to resources.’ The ‘regime of authenticity,’ according to Duara (Reference Duara2003: 29), ‘necessitates a continuous subject of history to shore up certitudes, particularly for the claim to national sovereignty embedded in this subject.’

In the PRC the construction of a continuous or linear history for the purposes of claiming national sovereignty includes an emphasis on ‘lost’ territories in the South China Sea, a point made by Liang Qichao when he praised the Zheng He expeditions. The ‘Maritime Silk Road’ narrative, publications on the history of Sino-foreign interactions, and findings from underwater archaeology are harnessed to support the PRC’s claims to its maritime heritage and sovereignty over such lost territories. This is done by underscoring the PRC’s ‘continuous’ history of engagement with the maritime world, contending that China was ‘the first country to discover, name, and explore’ sites in the South China Sea and beyond, and asserting cultural rights over shipwrecks in disputed zones. However, as this section demonstrates, the process of claiming heritage over the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ has been extremely messy due to the individual aspirations of coastal provinces and cities. Similarly, the fusing of underwater cultural heritage and territorial claims by the PRC in the South China Sea, as the next section argues, has complicated exploitation of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ idea in ‘soft power’ diplomacy. Together, this section and the next illustrate that the rhetoric and the intended practical applications of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ idea by the PRC are at odds with one another, leading to various contradictions and frictions.

Already in 1992, a year after it had hosted UNESCO’s Maritime Route Expedition, Quanzhou had drafted a plan to nominate the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ for acceptance onto the UNESCO World Heritage List (Gong et al. Reference Gong2011: 119). However, it was not until 2001, the so-called ‘Year of the Silk Roads’, that the issue of nominating the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ was extensively discussed by representatives of various coastal provinces and cities in the PRC. This revived interest may have been related to the PRC’s ongoing negotiations with the UNESCO World Heritage Centre regarding the nomination of cultural properties along the ‘Silk Roads’. Coastal provinces and cities also closely followed the PRC’s pending application to the World Trade Organization (WTO), with its potential to boost trade and tourism in these places. The broader backdrop was frequently noted at the ‘Silk Roads’ conferences held in 2001. At the conference in Ningbo, for example, representatives from seven Chinese port cities, including Guangzhou, Quanzhou, and Ningbo, signed the so-called ‘Ningbo Consensus’ (Ningbo gongshi 寧波共識)Footnote 36 on submitting a joint application for the inscription of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ on the World Heritage List. The first point in the Ningbo Consensus highlighted this connection to contemporary WTO discourse: ‘at the cusp of the 21st century and in the middle of the historical surge to construct an Oceanic Civilization and China’s entry into the WTO, the vigorous propagation of the long history of “Maritime Silk Road” culture is a historical opportunity and the choice of the times’ (Gong et al. Reference Gong2011: 120).

Despite this agreement, however, a key debate emerged among the signatories of the Ningbo Consensus over the site of the earliest maritime interactions. The various options put forth by the provinces included the Neolithic site of Hemudu 河姆渡 (near Ningbo), Xuwen 徐聞 (in present-day Guangdong), Hepu 合浦 (in Guangxi), and Guangzhou (Geng Reference Sheng2005: 43–63). In order to make their respective cases, the provinces and cities quickly established their own working groups and research institutions. In 2002, for instance, the Fujian provincial government set up a ‘leadership group’ to draft its own proposal for the UNESCO listing. Similar steps were also taken by Guangdong province and the city of Ningbo. Some of these coastal provinces and cities also started building museums to showcase their unique maritime links.Footnote 37

Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, in addition to this intra-provincial competition to seek recognition as the most important and earliest ‘Maritime Silk Road’ site, there also seems to have been a lack of coordination between the competing coastal initiatives and the Chinese National Commission for UNESCO, which was responsible for formally nominating a site for UNESCO World Heritage listing. In August 2003 and July 2004, UNESCO sent ‘expert missions’ to China that aimed to ‘develop a systematic approach towards the identification and nomination of the Chinese section of the Silk Road, and in particular the Oasis Route which, together with the Steppe Route and the Maritime Route, is one of three intercultural routes along the Silk Road, that will tell the story of the Chinese Silk Road in a comprehensive manner’.Footnote 38 These expert missions were part of UNESCO’s emphasis in the early 2000s on collaboratively developing a ‘transboundary nomination for the Silk Roads’ (Williams Reference Williams2014: 3). Ten countries, including the PRC, actively participated in this ‘UNESCO Serial Transnational World Heritage Nominations of the Silk Roads’ project and attended several sub-regional workshops, starting in Almaty in November 2005 and leading to the first meeting of the Coordinating Committee for the Silk Roads Serial Nomination in Xi’an in November 2009.

During this protracted process, proposals for sites to be included on the ‘Silk Roads Tentative List’ in the serial nomination process were collected from participating countries. In March 2008, the PRC submitted a list of 48 such sites. Ningbo and Quanzhou were included in this list under the category of the ‘Sea Route of the Silk Road’.Footnote 39 After the 2010 International World Heritage Expert Meeting in Ittingen, Switzerland, which outlined the recommendations for the nomination of serial sites for UNESCO World Heritage status,Footnote 40 the Coordinating Committee of the Serial Transboundary World Heritage Nomination of the Silk Roads deliberated and decided on drafting their application based on distinct ‘corridors’ instead of submitting a comprehensive ‘Silk Roads’ application because of the multistate nature and complicated process of a joint nomination. Consequently, China, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan were the first to jointly apply for one section of the overland ‘Silk Roads’—the Chang’an–Tianshan Corridor—to be included on the UNESCO World Heritage List for 2011, and it received inscription in 2014.Footnote 41

It is not clear why only Ningbo and Quanzhou were included in the March 2008 list of Silk Road sites submitted by the PRC. Internal discussions from 2006 indicate that Guangzhou was also supposed to be part of that list. In fact, while the list was being compiled, Nanjing, Yangzhou, Penglai, Beihai, Fuzhou, and Zhangzhou all expressed an interest in being included (Gong et al. Reference Gong2011: 120). After the decision of the Coordinating Committee of the Serial Transboundary World Heritage Nomination of the Silk Roads to segment the ‘Silk Roads’ application according to corridors, a reassessment of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ sites took place within the Chinese Cultural Relics Department. This resulted in the decision to include nine coastal cities in the PRC’s Tentative List submitted to the World Heritage Committee.Footnote 42 The Tentative List, according to World Heritage Committee guidelines, should include properties that states ‘consider to be cultural and/or natural heritage of outstanding universal value and therefore suitable for inscription on the World Heritage List’. The guidelines also mention that ‘States Parties should submit Tentative Lists, which should not be considered exhaustive, to the World Heritage Centre, at least one year prior to the submission of any nomination’.Footnote 43

At a conference held to deliberate on the nomination of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’, held in Quanzhou in 2014, representatives from the nine coastal cities selected for the Tentative List signed the ‘Quanzhou Consensus’ (Quanzhou gongshi 泉州共識) affirming their joint efforts during the application process (Chu and Chen Reference Chu and Jianzhong2016: 2–4). However, in February 2016, when the Chinese National Commission for UNESCO formally submitted the Tentative List for the ‘Chinese Section of the Silk Roads’, Beihai and Penglai were not included. More significantly, the submission of this Tentative List came a few days after the organization had separately nominated ‘Historic Monuments and Sites of Ancient Quanzhou (Zayton)’ for the Tentative List.Footnote 44 And in 2017 only Quanzhou was formally nominated by the PRC for inscription on the World Heritage List.

The reason for nominating Quanzhou and not the other coastal cities that had signed the Quanzhou Consensus is revealed in the ‘Comparative Analysis’ section of the PRC’s application to UNESCO (ICOMOS 2018).Footnote 45 The ‘State Party’, it states, compared

Quanzhou with other Chinese port cities that form parts of the ‘Great Maritime Routes,’ including: Guangzhou, Ningbo, Yangzhou, Beihao, Zhangzhou, Fuzhou, Nanjing and Penglai. Each of these has important cultural heritage features relating to maritime routes and trade. The State Party considers that Quanzhou preserves the largest number of historic buildings with different typologies linked to the maritime trade. The analysis also emphasized the significance of the proposed property during the Song and Yuan dynasties. (ICOMOS 2018: 71)

This issue of tangible buildings and monuments authenticating maritime interactions and heritage may also have been the reason for the messiness that marked the discussions, debates, and negotiations among the coastal cities that were vying over the heritagization of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’. In addition to the fact that Quanzhou houses the greatest number of surviving structures connecting it to the Indian Ocean world, the city was also mentioned in the works of Marco Polo (1254–1324) and Ibn Battuta (1304–1369), confirming, according to the application, its role in East–West connections and the ‘outstanding universal value’ that sites nominated for the UNESCO World Heritage List must demonstrate. Moreover, as noted above, Quanzhou had been involved with UNESCO’s Silk Roads Project since the early 1990s, another point highlighted prominently in the application. In other words, the Chinese National Commission for UNESCO may have concluded that Quanzhou had the best chance of achieving UNESCO inscription compared to the other coastal cities, or even to a joint application under the rubric of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’.Footnote 46

During the evaluation process, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) consulted its International Scientific Committee on Underwater Cultural Heritage, its Committee on Historic Towns and Villages, and ‘several independent experts’. In its final decision, ICOMOS rejected all the arguments and criteria presented in the application and, in its report dated 14 March 2018, recommended that the ‘Historic Monuments and Sites of Ancient Quanzhou (Zayton), China, should not be inscribed on the World Heritage List’ (emphasis in the original) (ICOMOS 2018: 79). Among the key reasons for this rejection were: 1) the failure to provide a satisfactory analysis of Quanzhou comparing it to other sites in China and elsewhere; 2) the lack of any proper justification for the inclusion of the 16 sites from Quanzhou in the application; and, more pertinently, 3) the unconvincing overall framework of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ idea that was used to make the argument for the city’s importance (ICOMOS 2018: 68–79). In fact, in several places in its evaluation, ICOMOS pointed out the inadequacies of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ framework employed in the application. For example, it registered a concern that ‘current global thematic studies are not yet able to establish a clear overall thematic framework on the maritime silk routes that could guide the consideration of properties for the World Heritage List’ (ICOMOS 2018: 71). It clarified further that,

For the most part, the idea of ‘maritime silk routes’ underpins the justification for Outstanding Universal Value, but … this concept is not yet well established. The network of trade routes across the East and South China Seas and across the Indian Ocean region changed significantly over time as certain polities embarked on trade and military campaigns, and port cities waxed and waned in their importance. The city formed part of a cluster of port cities in China and was part of a wider network of port cities in the Indian Ocean Region. It is important to read the significance of Zayton with this larger picture. (ICOMOS 2018: 72)

In addition to questioning Quanzhou’s, and more broadly China’s, exclusivity over and cultural ownership of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ idea, ICOMOS also objected to the ‘associations drawn’ in the application with the Zheng He expeditions in order to highlight the importance of Quanzhou. The report pointed out that ‘there is no correlation between the period of Quanzhou’s peak (10th–14th centuries) and the later (fifteenth-century) voyages of Zheng He’. It also noted the existence of ‘contested interpretations about the regional historical impacts of Zheng He’s voyages because they involved military campaigns and battles in Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka. ICOMOS therefore considers the linking of this later period of history, and the voyages of Zheng He in this nomination to be controversial; and that neither the associations with Zheng He or Marco Polo are directly relevant to this serial nomination’ (ICOMOS 2018: 74).Footnote 47