Introduction

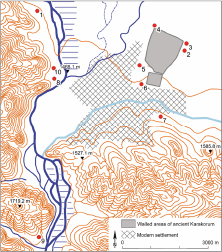

Karakorum, the first capital of the Mongol empire from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, has often been described as a cosmopolitan city. This take on cosmopolitanism springs from an everyday, colloquial understanding of the word, which implies the co-presence of people, materials, thoughts, or ideas from different parts of the world within a single locale. Arguably, most mentions of cosmopolitanism in scholarly writings stem from this casual, simple understanding.Footnote 1 Looking at the history of the term ‘cosmopolitanism’,Footnote 2 however, we recognize that the concept has more to offer than just a synonym for multiculturalism or the possibilities of expanding networks of trade. To explore more complex processes of cosmopolitanism was the professed goal of the conference that provided the starting point of this article.Footnote 3 The Mongol empire, the largest contiguous land empire in world history and, more precisely, its first capital Karakorum in Central Mongolia, provides a suitable case study for such an endeavour (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The location of Karakorum in the Orkhon valley, Mongolia. Source: Author. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

From Chinggis Khan’s (r. 1206–1227) rise to Great Khan of the unified Mongolian tribes in 1206, he and his successors went on to conquer large stretches of the Eurasian landmass, culminating in the conquest of the Song in 1279 by Khubilai Khan (r. 1260–1294). At this point, the Mongol empire had been divided into four more-or-less independent successor states—the Yuan empire (including the Mongolian heartland), the Ilkhanate, the Golden Horde, and the Chaghadaid Khanate. The Mongols established the Yuan dynasty in China and were able to hold the government until 1368, when they were forced to flee and ultimately ended up as the Northern Yuan in their Mongolian homelands.

During the heyday of these Mongolian states, however, Eurasia witnessed hitherto unheard-of scales and ranges of trade and intercultural exchanges, often attributed as Pax Mongolica.Footnote 4 Karakorum, the initial capital of the empire, founded by Chinggis Khan in 1220 and erected under his son and successor Ögödei Khan (r. 1229–1241) in the Orkhon valley from 1235 onwards, served as a trading hub for the Mongolian steppes. The city continued to thrive and take part in these exchanges well beyond its own demotion in 1260 when Khubilai conferred the capital status first on Shangdu and later on Dadu (modern Beijing). According to our current knowledge, the city’s history only ends in the early fifteenth century, at which time changing political realities possibly undermined the rationale for a city in the steppes.Footnote 5 The construction of the Buddhist monastery Erdene Zuu in 1586 on top of what is assumed to be the former palace area marks a more definite end point in the history of Karakorum. Building blocks and inscribed stones from Karakorum were used as spolia for the erection of some of the Buddhist temples in the monastery.Footnote 6

Excavations in the middle of the city in the early 2000s uncovered areas of the artisans’ quarter, where deposits of up to four metres in depth contained remains of residential quarters associated with intense manufacturing workshops, covering a wide spectrum of crafts, e.g. blacksmithing, silver- and goldsmithing, glass works, and mineral stone works.Footnote 7 There is abundant evidence of imported goods and long-distance trade based on the provenance of finds and materials. Porcelain and other glazed ceramic wares were, for example, imported from China.Footnote 8 The overall number of glazed wares speaks to the assumption that Karakorum’s population had easy access to these goods, some of which were brought there from over 2,000 kilometres away. Other examples underline the function of Karakorum as a trading hub. Glass objects of different compositions, which point to origins in Central Asia and China, cast iron ingots probably imported from China, and an astounding variety of foodstuff, some of which, such as rice and plums, must have been imported from far away, can all be seen as a reflection of the far-reaching trade networks of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.Footnote 9

The Mongol empire and Karakorum thus fit the description of the colloquial sense of cosmopolitanism and provide a springboard into a deeper inquiry into cosmopolitanism. Historiographical works show the cross-cultural engagement of people who were building successful intercultural careers in the vast empire and the active encouragement they received from the Mongol Khans.Footnote 10 These people were mobile elite personnel, most of whom were responsible for the administration of the empire, but also included other specialists from fields as diverse as medicine and astronomy. Bilingual administration under Yuan rule promoted the mixing of different population groups while preserving the Mongolian language.Footnote 11 In particular, the merchants, Marco Polo being the most well-known, are often portrayed as cosmopolitan agents whose language skills were highly esteemed.Footnote 12 Trade vocabularies, such as the Rasûlid Hexaglot, compiled during the heyday of trade relations across the Eurasian continent bear witness to the importance of communication in different languages.Footnote 13 Juvaini, for example, was struck by the numerous scribes of different languages when visiting Karakorum.Footnote 14

A limited set of about 14 stone inscriptions, mostly found as spolia within the monastery of Erdene Zuu, provides clues as to the use of language in Karakorum by different actors.Footnote 15 All of these inscriptions can be attributed to the time frame of 1327 to around 1350. Ten of the texts are in Chinese and deal with the commemorations of high officials of Karakorum, the erection and renovations of a Confucian shrine and school as well as a shrine for the Three Sovereigns, and relief policies during famines. As such, they were probably all commissioned by the province administration of Lingbei stationed in Karakorum. The choice for Chinese-only inscriptions stands in contrast to two inscriptions from 1347 and 1348, probably both commissioned by the emperor Toghon Temür and both displaying bilingual versions of the text in Mongolian in the adapted Uighur script and in Chinese.Footnote 16 The inscription from 1347 commemorates the building of the ‘Pavilion of the Rising Yuan’ and can be related to the Buddhist temple uncovered in the southwest part of Karakorum.Footnote 17 The simultaneous use of these two scripts and languages can be seen as one strategy of Toghon Temür to embrace different population groups in his realm, in contrast to the earlier exclusive use of Chinese by the city administration, which—judging by their names—mostly involved Chinese personnel. The preservation of native language identity is likewise represented by the two known Persian inscriptions, dated to 1332 and 1341/1342.Footnote 18 The practice of commissioning inscriptions in Karakorum therefore points to a difference in attitude among different groups: while imperial policy clearly included a bilingual government, local groups in Karakorum clung exclusively to their own language. This observation leads to the question of whether different groups in Karakorum were truly cosmopolitan.

The main reason why cosmopolitanism is attributed to Karakorum can rightfully be seen in William of Rubruck’s detailed description of the city. The Franciscan monk travelled to the Mongolian steppes from 1253 to 1254 in order to proselytize and to look for European captives who provided crucial skills for their new Mongolian masters.Footnote 19 The monk spent several months in the city in 1254, so he was intimately familiar with its layout and its people. Rubruck mentions a colourful mix of people and structures: Möngke Khan (r. 1251–1259), the palace, ‘all the nobles from any place up to two months’ journey away’, envoys, one quarter for Muslim merchants with bazaars, one quarter for Chinese craftspeople, Buddhist temples, Muslim mosques, a Christian church, and court scribes.Footnote 20 Adding to this list are his personal encounters, for example with Guillaume de Boucher, a French artisan; ‘Hungarians, Alans, Russians, Georgians and Armenians’; and envoys of a sultan of India.Footnote 21 However, not all of these people dwelt voluntarily in Karakorum; artisans, for example, were prized booty in the Mongol conquests, and Guillaume de Boucher was one of those captured in Hungary and brought to the Mongolian steppes.Footnote 22

The image of the city as a gathering place for different groups is corroborated by other sources. At the beginning of the fourteenth century, the Persian Rashīd al-Dīn mentions markets and storehouses, that the construction of the palace area had been carried out by Chinese craftsmen, and that nobles were asked to build residences nearby the khan’s palace.Footnote 23 The Arab Ibn Fadl Allah al-’Umari wrote in the mid-fourteenth century that the city served as the main station for the Mongol military and had several imperial workshops for the production of fine textiles and luxurious goods.Footnote 24

We must also keep in mind that the population of Karakorum changed dynamically throughout the year due to the mobility of the Mongol court and seasonal fluctuations in merchants’ routes.Footnote 25 It is difficult to estimate the permanent, steady parts of the population of Karakorum, but a mixture of craftspeople, administrative staff and scribes, religious professionals, and stationary troops might be assumed.

The city thus emerges as a place full of opportunities to encounter people of different cultural backgrounds, but this does not tell us about the mindsets of the people and how they engaged with one another. There is research that has treated themes that relate to issues of cosmopolitanism in the Mongol empire from a distinct historiographical perspective,Footnote 26 but to the knowledge of the author, there is no dedicated discussion of cosmopolitanism as such that concerns the heart of the Mongol empire. Studies of cosmopolitanism with an explicit focus on archaeology and material culture are few.Footnote 27 This article presents the first foray into this field for Karakorum. Cosmopolitanism certainly evokes the picture of modern, multicultural city cultures. The question here, however, is if the same can be said about Karakorum. Did the inhabitants of Karakorum make use of the multitude of different opportunities, and if yes, how did they engage with groups perceived as different from their own?

First, a closer look at the history of the term ‘cosmopolitanism’ and its layered meanings will serve to provide an understanding of the term in contexts that are relevant and amenable to an archaeological approach. Key cultural areas will then be explored based on the actual archaeological findings from Karakorum, underpinned by evidence from written sources, to tease out the nature of everyday cosmopolitan practices in the city. The goal of this article is therefore twofold: to provide a better understanding of Mongol period city culture within steppe societies and to explore how material culture might reflect the notion of cosmopolitanism beyond what is portrayed historiographically.

Terms and models

Even the most exhaustive works on cosmopolitanism have found it to be indefinable.Footnote 28 More often, we find the term used as a good-sounding buzzword. Definitions of cosmopolitanism stem from a wide range of disciplines and cover many and very different aspects. For Biedermann and Strathern, dealing with early modern history, cosmopolitanism stretches between two poles as it embodies heterogeneity, the occurrence of plurality within one locus, and homogeneity, in the sense of being part of a larger translocal community, e.g. the Buddhist ecumene, at the same time.Footnote 29 In modern history, cosmopolitanism has also been framed as a modern political ideal and agenda. Here, the emphasis is ‘on cosmopolitanism as a practice, a cultural form, that is, “a way of being in the world”’.Footnote 30 To anthropologist Ulf Hannerz, cosmopolitanism is, foremost, a personal stance and ‘state of mind’ of people who are willing to engage with diverse cultures.Footnote 31 Consequently, cosmopolitanism can likewise be seen as a kind of competence. It is both a general skill of manoeuvring with other cultures and, more specifically, cultural competence within a particular culture.Footnote 32 Each of these perspectives reveals a much deeper meaning of cosmopolitanism than the mere coexistence of foreign people and materials in one place. The crucial element is the consideration of how individuals situate themselves vis-à-vis foreign elements.

So, where did the concept of cosmopolitanism originate? The initial coining of the term is ascribed to Diogenes the Cynic in ancient Greece (the fourth century bce), who, when asked in exile to which city-state he belonged, called himself a kosmopolitês, which translates as ‘citizen of the world’. However, even concerning the record of this event, scholars have put forward different exegeses. According to Martha Nussbaum, Diogenes wanted to convey a shared humanity, irrespective of origin or other divides (gender, status, wealth). This notion of cosmopolitanism, which is imbued with a sense of moral duty, has been very influential in modern political and historical scholarship.Footnote 33 Other scholars underlined Diogenes’s oppositional stance and criticized Nussbaum’s take on cosmopolitanism, since it undermined the challenge faced by marginalized and dislocated people in environments culturally different from their own.Footnote 34 The positive connotation ascribed to cosmopolitanism is furthermore deeply entwined with Immanuel Kant’s (1724–1804) ‘hospitality’, the idea of being responsible for beings other than yourself, which lay the groundwork for the emerging paradigm of human rights.Footnote 35 This positive meaning of cosmopolitanism is likewise prevalent in modern political philosophy.Footnote 36

It has therefore been argued that cosmopolitanism is first and foremost an attitude and a mindset, and that it comprises the freedom to act in this way voluntarily. It goes beyond the reductive view of cosmopolitanism seen as the intensification of transregional trade and exchange networks. At the same time, cosmopolitanism is not a neutral term; it is charged with political ambition advocated as a moral goal for modern societies. Retrospectively projecting modern values onto the past risks producing results that are incongruous with past life experiences. But, as we have seen, there is not one way to understand cosmopolitanism. Rather, it has been stated that it might be ‘uncosmopolitan’ to define cosmopolitanism,Footnote 37 which answers to the variance in approaching cosmopolitanism within and between disciplines. It might be then more fruitful to follow a multiplicity of approaches, namely ‘cosmopolitanisms’ and to ‘simply look at the world across time and space and see how people have thought and acted beyond the local’.Footnote 38 The question of ‘how people acted’, when we refer it to archaeology, marks a crucial shift in the approach of cosmopolitanism as it looks into practices of human behaviour, which leaves materials traces. It opens up the possibility for sources and methodologies of archaeology to be applied. So far, there have been relatively few discussions of this concept in archaeology, compared to other disciplines.Footnote 39

The philosophical definition of cosmopolitanism by which all humans belong to a single community is challenging to apply in archaeology. Coningham et al. opt for a wider definition of cosmopolitanism as a reflection of multiculturalism and a general worldliness. Through their analysis they identify instances of different communities and their relationships and identities.Footnote 40 In his study on medieval Ethiopia, Insoll follows Hannerz’s definition of cosmopolitanism ‘as a willingness to engage with the other’, which he sees manifested ‘through material evidence (e.g., trade goods, images, coins, architecture, epigraphy and burial practices) that increasingly demonstrates extensive commercial, religious, social and cultural interaction’.Footnote 41 This approach sets the bar quite low for identifying cosmopolitanism, as it simply invokes the equation of the occurrence of foreign objects with cosmopolitanism. This simple equation should rather be overcome. A more challenging undertaking has been put forth by Kate Franklin.Footnote 42 Answering to post-colonial critiques of cosmopolitanism as a white, male, elite project, she follows Pollock in her endeavour to discern everyday practices of cosmopolitanism, especially as acts of hospitality.Footnote 43

All the different takes on this term are unified in seeing cosmopolitanism as a certain understanding, a certain attitude of how individuals situate themselves in relation to others. Therefore, cosmopolitanism is not a policy. It goes beyond multiculturalism, which rather describes a coexistence of different groups.Footnote 44 It is also not a theory in the sense that it explains a specific situation, observation, or phenomenon. Rather, cosmopolitanism provides instead a certain lens through which to re-examine established findings.

It would be all too easy to uncritically identify cosmopolitanism among Karakorum’s inhabitants on the basis of the mere occurrence of different materials perceived as foreign. Delanty assumes that exchange and mobility are preconditions for cosmopolitanism, but that they were certainly not the same.Footnote 45 Certainly not every tourist who spends most of their time in a resort engages meaningfully with their new environment.Footnote 46 Thus, not all mobility equals cosmopolitanism.

The already mentioned risk involved with applying this etic concept and projecting it into the past highlights more than just anachronism. Here, the goal is not to identify the origins of cosmopolitanism, but to use this concept as an analytical stance from which to learn more about how different groups encountered one another, and how people engaged in their daily lives at Karakorum. Drawing on Franklin, cosmopolitanism should be seen as action and furthermore applied to members of society normally outside the purview of cosmopolitanism.Footnote 47 For the purpose of this article, I see cosmopolitanism as denoting a purposeful engagement of individuals with alien groups and particular practices in their positioning towards such groups, most often understood in cultural/ethnic terms.Footnote 48

Material views

Practice theory in archaeology, which mirrors the shift away from thinking of cosmopolitanism as a state of mind or attitude and instead towards acts of cosmopolitanism, is useful for these new ways of engaging with cosmopolitanism.Footnote 49 Simply put, habitual acts by human agents produce patterns in the material record that archaeologists can recognize later after factoring in taphonomic processes. Working on the assumption that cosmopolitanism was an explicitly lived practice among the inhabitants of Karakorum, we should be able to discern such acts of lived cosmopolitanism in the material record. Different aspects of material culture will be interrogated to test this hypothesis, and to establish how different groups engaged with one another. If everyday practices manifested in the material remains at Karakorum comprise the primary analytics, then any critique of cosmopolitanism as inherently Eurocentric may be untangled from the more apt uses of cosmopolitanism for which I argue in this article.Footnote 50

Lived cosmopolitanism can manifest in any field of everyday human activities and cultural practices. These include spatial organization and use of settlements, architecture, cuisine, religion, funerary rites, writing, dress and clothing styles, technology, and medicine. In this article, I specifically address manifestations in spatial organization and architecture, cuisine, religion, and funerary rites. Dress and clothing styles, although highly important for the expression of different identities and therefore for the identification of cosmopolitan practices, are not sufficiently represented in the archaeological record retrieved so far from Karakorum and are therefore not included in this study.

Delanty emphasized that material expressions of cultural fields can be seen ‘as media through which many social relationships and interactions are negotiated; archaeology can detail how the material world both engages, and is engaged in, the articulation of social identity, both of the individual and of the group’.Footnote 51 This article takes on the challenge of teasing out how cosmopolitanism is manifested in material culture through the combination of cultural fields and their related materials in order to hopefully provide a plausible picture of Karakorum city and its potentials of lived cosmopolitanism.

Spatial organization and architecture

In general, cities appear as sporadic phenomena in pastoralist empires. They rose and declined in tandem with larger confederations or empires and, in the eastern extremities of the Eurasian steppe belt,Footnote 52 they did not constitute a sustained urbanization process. The same holds true for Karakorum, which had been built at the behest of the Mongol khans. The city was planned and erected from scratch without prior settlements in its location—a phenomenon that might be coined as ‘implanted city’.Footnote 53

This observation can be fruitfully combined with environment-behavioural theory, which addresses how people shape their built environment and how this built environment in turn shapes human behaviour, and Amos Rapoport’s delineation of three levels of meaning attributed to the built environment: low-level meaning refers to visual cues that enable people to identify the accepted function and use of buildings and spaces; middle-level meaning refers to the communication of certain political or social statements, such as wealth or power, through buildings or cities; and high-level meaning pertains to the symbolic representation of cities specific to a cultural system.Footnote 54

Looking into the high-level meaning expressed by Karakorum, we have reason to presume a culturally specific, ideological plan in the city’s design. The layout is the most prominent argument in this respect (see Figure 2). As already discussed elsewhere,Footnote 55 Karakorum is categorically different from the models of either Chinese or Central Asian cities. Instead, nomadic cosmological programmes underlying the layout of the ordu (the imperial camp) and the spatial patterns of the nomadic mobile residence—the yurt—appear to have informed Karakorum’s design.Footnote 56 Per this programme, the palace was placed along the southernmost edge of the city, securing the Great Khan an unobstructed view to the south. At the same time, certain building elements and techniques, e.g. fired bricks and roof tiles, some of which are glazed, follow Chinese and Central Asian styles.

Figure 2. Annotated city map of Karakorum based on topographical and geophysical surveys. See online for the colour-coded version of this figure. Source: Author, Jan Bemmann, and Anna Stefanischin.

Another highly prominent feature of Karakorum is its wall. Compared to strictly square, or at the minimum, rectangular Chinese city walls,Footnote 57 the curiously asymmetrical layout of the Mongol city’s wall has attracted scholarly attention.Footnote 58 City walls, however, were not an essential feature of Mongol period urban sites.Footnote 59 Karakorum is the only Mongol period settlement in the northern steppes that was walled. This stands in stark contrast to Chinese traditions of city planning, where the wall is not only a defining feature, but the term ‘wall’ (cheng 城) is synonymous with ‘city’.Footnote 60 Ögödei Khan’s plan to surround the city with a wall speaks to his interest in this feature. Taken together, the layout of Karakorum displays a combination of different sources, from nomadic cosmological ideas to the appropriation of various architectural styles and features. This might reflect the open-mindedness of the Great Khans and their courts, as they were the decision-makers of the planning and establishment of the city.

The city’s layout exhibits further evidence of cosmopolitanism. But we should look not just to the collection of physical attributes that might signal cosmopolitanism. Returning to practice theory, we might ask, for example, in which way the city’s infrastructural and architectural layout might have hindered or actively encouraged the communication between different groups and their daily encounters. In other words, does the layout of the city manifest any elements indicative of a lived cosmopolitanism?

Taking a close look at the city’s throughways and road system, we discern no blockages or dead ends (see Figure 2).Footnote 61 Also, the spatial configuration does not show residential neighbourhoods separated by walls that could be used to shut off the area at night or times of distress, which is a major characteristic of cities in the Islamic world contemporary with Karakorum as well as the Chinese city of Chang’an during the Tang period.Footnote 62 The lack of physical barriers might indicate relative freedom for people to roam the streets of Karakorum, which is conducive to intergroup communication and exchanges. Rubruck’s description corroborates this interpretation. Judging by his experiences, he was free to navigate the city and interact with different people.Footnote 63

Architectural layouts of residences uncovered during excavations in the middle of Karakorum likewise support this observation. For instance, one house facing the street was the site of a workshop for non-ferrous metal works, which was probably open to the front to maximize the use of sunlight and air circulation (see Figure 3).Footnote 64 The layout of this workshop, which had been used shortly after the middle of the thirteenth century, therefore allowed ample interaction with passers-by and potential clients.

Figure 3. Workshop fronting the street in the middle of Karakorum and dating to the thirteenth century. A) Upper edge of wooden anvil stand protruding from soil. B) Ditch of street. C) Paved street. Source: Author, Bonn University.

The presence of religious buildings and houses used for Christian gatherings, as described by Rubruck, which have been partly evidenced by archaeological excavations, also provided public spaces for intergroup encounters and communication.Footnote 65 While these examples suggest that opportunities for interaction in Karakorum were at least tolerated and not actively hindered by the Mongol khans, other pieces of evidence distort this picture.

Rubruck mentions bazaars in the middle of Karakorum that are associated with Muslim merchants of Central Asian origin. His description of four markets situated at the four main gates to the city, however, raises questions: ‘At the east gate are sold millet and other kinds of grain although seldomly imported; at the western, sheep and goats are on sale; at the southern, cattle and wagons; and at the northern, horses.’Footnote 66 The animals mentioned here can be deemed core steppe ‘products’, probably brought by Mongolian pastoralists in the vicinity. It is peculiar that these people were apparently outside the gates: why was that the case? Is it because it would have been too messy to place animal markets inside the city? There would have been empty unbuilt areas for such markets, especially in the northern area within the walls of Karakorum. Or did the nomads prefer to stay outside the city proper? If so, we would have to exclude pastoralists from the mix of people under consideration who frequented the streets of Karakorum.

Moreover, public access to certain areas within the city was restricted. Apart from the palace, which was walled and controlled by four gates, there is a cordon of walled compounds of varying sizes between the palace area and the densely built middle of the city.Footnote 67 While the symmetrical layout of buildings within these walled areas might point to their religious function, some of these buildings might have been housing for the aforementioned nobles who were asked to build residences near the Great Khan’s palace. Their different sizes might be interpreted as differences in wealth and social status, which brings us to the identification of different neighbourhoods and their possible social differentiation.

Excavations by Russians, Mongolians, and Germans in the middle, densely built areas of Karakorum revealed evidence of households occupied with craft activities.Footnote 68 We see here the evidence of one of the two quarters mentioned by Rubruck, which he differentiated based on the profession and ethnicity of the residents. Two recent studies, partially based on new geophysical and topographical surveys of Karakorum,Footnote 69 took the first step in identifying the layout and types of spatial zones, e.g. residential or civic-ceremonial. The authors found that ‘standardized building forms or floor plans cluster in different areas and along the main streets, which could indicate a social and/or occupational differentiation of the neighborhoods’.Footnote 70 However, for now, the archaeological data only show us the occupation, and not the ethnic identity, of the residents. We can identify zones within Karakorum that were segregated by social status, religion, and occupation. If, and how, different groups followed possible cosmopolitan practices will be further discussed in the next section on the art of cuisine.

Cuisine

Cuisine encompasses the whole range of dietary behaviour, from what we eat, how we prepare the food to how we eat the food. It is highly adaptable to changing circumstances, and most ingredients can be exchanged for an equivalent that is easier to come by in a different environment. It therefore provides a window into how people coped with fluctuating food supplies in Karakorum.

Human remains found within and in the surroundings of Karakorum have not been fully analysed for a reconstruction of human diet.Footnote 71 Botanical and faunal data from excavations in the early 2000s provide another data set for reconstructing the diet of the populace.Footnote 72 So far, 10 per cent of the overall faunal collection retrieved during these excavations were analysed. Although the animal bones cannot be related to individual households since animal bones retrieved from the street layers were analysed together with materials from the residential quarters, the results are still useful to provide a broad picture of consumption patterns in the city.Footnote 73 Based on characteristic butchering marks, von den Driesch and colleagues found that sheep dominated the dietary intake of meat, followed by cattle, and minor proportions of horse and goat.Footnote 74 These are the main species of locally available animals. Kill-off patterns, mostly of juvenile male sheep, correspond to herd composition dictated by optimal herd management practices.Footnote 75

Additionally, birds, mostly chicken, were consumed. Scarce finds of dog and pig bones point to their minor role in dietary intake. The consumption of pork is often associated with people of Chinese origin.Footnote 76 In the case of Karakorum, the authors suggest that—since conditions in the Orkhon valley were not ideal for raising pigs—the pig bones might point to the consumption of dried or salted pork imported from the south.Footnote 77 Judging by the low number of pig bones in the entire faunal collection uncovered in the middle of Karakorum, these imports were either very limited or did not reach the people living there as they may not have been part of the ordinary food allotments.

Hunting, or at least the consumption of hunted wild animals, did not play a substantial role in the food acquisition strategy. A low proportion of wild animal bones in the faunal collection has been similarly described for an adjacent area excavated in the 1940s.Footnote 78 Fishing, probably in the nearby Orkhon, in contrast, was a major strategy for the supply of proteins.Footnote 79

A comparison with faunal data retrieved from the area of the Buddhist temple in the southwestern part of the city reveals slight differences in the pattern of meat consumption. Here, we can assume a different social makeup of the consumers, who were probably Buddhist monks and potentially servants needed for the maintenance and running of the temple. These people preferred horse and cattle over sheep and goat, which might point to ethnic differences in meat consumption.Footnote 80

Similar to the faunal remains, only a subset of the soil samples taken during excavation in the middle of Karakorum was analysed for macrobotanical remains, which severely limits the effective evaluation of identified plant residues throughout the whole settlement sequence.Footnote 81 Most of the botanical remains identified are millet, barley, and common wheat; there are also small quantities of foxtail millet. Since these are all summer crops and the researchers also identified chaff and straw, it seems likely that these cereals were cultivated locally in the Orkhon Valley.Footnote 82

Winter crops, namely oat, rye, dinkel wheat, and einkorn wheat were found in far smaller quantities and might have been either locally produced or imported from Central Asia or China.Footnote 83 There were only two specimens of rice, which was certainly imported from China. The scarcity of this crop in Karakorum, which was, and still is, a staple in South Asian cuisines, is notable.Footnote 84 Possibly due to the abundance of animal protein, oil plants and pulses, which might have been locally grown, did not form major components in the diet.

Remains of a variety of spices, vegetables, and fruits that could be gathered in the wild, e.g. strawberries, pine nuts, juniper, and caraway, have also been identified, although they are rare due to taphonomic processes.Footnote 85 Some of the plant types identified in the macrobotanical remains could not be grown in central Mongolia and must have therefore been imported, most likely from China or Central Asia. Among them are grapes, figs, dates, plums, and black pepper.Footnote 86 All in all, the archaeobotanists identified more than ten different species of vegetables and spices, 20 species of fruits and nuts, and ten different Cerealia, which, in their view, indicate a varied diet similar to patterns found in medieval towns of Western Europe.Footnote 87 The limited number of macrobotanical remains recovered from the excavations of the Buddhist temple does not allow for a comparison.

Overall, the patterns of meat consumption in the middle of Karakorum show that foreigners had to adapt their potential meat preferences to that which was available in the Mongolian steppes. The tastes of the potentially Chinese populace were only sparingly accommodated by the supply of pork meat or imports of rice. The relative importance of fishing might indicate that people had to supplement their daily calories strategically. Furthermore, as Rubruck details, some Christian dependants were not sufficiently supplied with food by their Mongolian masters.Footnote 88 His observation that grain was not always attainable in the markets of Karakorum also bears witness to the fragility of the supply of bulk goods from outside the region.Footnote 89

We may now conclude that the people living in the middle of Karakorum, who probably originated from China, Europe, and Central Asia, embraced their new place of residence and, as cosmopolitans, consumed foods that were not normally part of their diets. However, the restricted availability of different plants, legumes, and meats might have led to a situation where people had little choice in the kinds of food they could consume daily, but rather had to make ends meet from the available resources.

A recipe book from 1330 written by Hu Sihui paints a rather different picture with regard to the food practices of the Mongolian emperors.Footnote 90 His ‘Proper and Essential Things for the Emperor’s Food and Drink’ (‘飲膳正要Yinshan Zhengyao’) can be portrayed as a fusion of Mongolian, Turkic, South and West Asian, and Chinese cuisines.Footnote 91 Furthermore, the ability to offer a diverse range of foods has been interpreted as a power display at the Mongol court.Footnote 92

Another way to look into cooking and eating is through the pottery that was used and discarded by the inhabitants. The majority of glazed ceramic wares found in the middle of Karakorum was imported from China (84.6 per cent) and Central Asia (1.3 per cent). They are mostly bowls and plates used for eating and drinking. Glazed wares of unknown, possibly local, provenance (14.1 per cent) are mostly storage vessels.Footnote 93 Locally produced grey, unglazed ceramic pots as well as iron and bronze cauldrons seem to have been used as cooking ware.Footnote 94

The range of ceramic ware at Karakorum differs greatly from that of Yanjialang, Inner Mongolia, in terms of vessel shape and use.Footnote 95 Assuming that the function of the items had remained the same, the lack of certain objects in Karakorum might indicate that the imports were driven by Mongolian choices and not necessarily by those of the inhabitants who used the ceramics in the middle of Karakorum. According to Paul Buell, the Mongols disseminated their predilection for liquid meals, mostly soups and broths, across Eurasia, which is expressed in a corresponding surge in demand for specific vessel forms, namely glazed bowls.Footnote 96 This attests to Eurasian culinary adaptability and flexibility.

Religion

The Mongol rulers were renowned for their pluralistic attitude towards religion.Footnote 97 For example, they offered tax exemptions to religious professionals.Footnote 98 As a trade-off, the rulers profited from prayers and the spiritual potency attributed to these religious professionals.Footnote 99 The practice of holding interfaith debates at the court provided a venue to negotiate political power and can likewise be seen in the light of the khans’ cosmopolitan attitude.Footnote 100 At the same time, the khans were known to react strongly and violently against perceived abuses of their own customs.Footnote 101 The roots of the Mongols’ particular stance might have been grounded in their immanentist religious practices.Footnote 102 The coexistence of diverse religious communities in Karakorum attests to this practice of religious pluralism and also points to a lived cosmopolitanism.Footnote 103

In the words of Rubruck, ‘There are twelve idol temples belonging to different peoples, two mosques [mahumnerie] where the religion of Mahomet is proclaimed, and one Christian church at the far end of the town.’Footnote 104 Two of these places were identified through excavations and both date to the thirteenth century. A building complex within the northeastern walled area of Karakorum was possibly used by the Church of the East and potentially reused as a Buddhist temple.Footnote 105 With a reconstructed dome roof, the earlier building phase A reflects Central Asian building styles, while the later phase B follows Chinese building traditions.

Another building complex in the southwest, formerly thought to be the Ögödei palace, was positively identified as a Buddhist temple.Footnote 106 The architecture of this building combines ideas from Tibet with building techniques from China.Footnote 107 Clay figurines of bodhisattvas as well as fragments of wall painting from inside the building represent ‘the “International style” of the 12th to 14th century, which is characterised by Indo-Nepalese, Tibetan, Tangut and Chinese elements’.Footnote 108 The construction of this building shortly after the destruction of the Western Xia in 1227 by Chinggis Khan, along with the identified artistic styles, has led to the assumption that Tangut craftspeople were brought to Karakorum to build this temple.Footnote 109 The style of architecture therefore has diverse origins and might also reflect the backgrounds of craftspeople from different parts of the empire during certain periods. There is a noteworthy decline of objects of Central Asian provenance, e.g. glazed ceramics and glass, in the fourteenth century.Footnote 110 This decline might be explained by shifting political alliances rather than as a reflection of changes in consumer choice. Nevertheless, the coexistence of various religions and architectural styles still highlight the openness of early Mongol Great Khans.

They not only tolerated the co-occurrence of different faiths in their capital, they also actively built temples, as detailed in the inscription from 1347 mentioned earlier.Footnote 111 The bilingual inscription was probably installed in the so-called Great Turtle of Karakorum, a landmark of the city (see Figure 4). This stone statue, situated less than 50 metres south of the Buddhist temple, is probably in its original position.

Figure 4. The stone turtle of Karakorum with the monastery of Erdene Zuu in the background. Source: Author.

The turtle represents ancient Chinese imaginary worlds; prior examples can be found in Mongolia in the old Turkic memorial sites of Khöshöö Tsaidam, not far from Karakorum.Footnote 112

The inscription praises Buddhism several times. Toghon Temür, for example, is placed in the tradition of the Mongolian Great Khans Ögödei and Möngke, who are invoked as positive role models, and described as promoters of Buddhism and wise men. At the same time, these rulers had located their centre of rule in the Mongol heartland. By joining this tradition, Toghon Temür affirms his Mongol origin and might thus refute critiques of him being too Sinicized.Footnote 113

The turtle’s pictorial programme and its inscription, as well as the use of different scripts and languages, can be seen as another example of the Yuan ruler’s open attitude: Buddhists, Mongolian traditionalists, and followers of general Chinese ideas could all feel equally addressed. This of course is only true for those who had access to the temple precinct and who were literate in one or both languages and the accompanying pictorial programme.

Rubruck’s travel report leaves the impression that the city’s population was divided along ethnic and religious lines. His description of different quarters is one example, even though this portrayal might have been dictated by his world view of how towns should look, as the ghettoization of people of Jewish faith was well underway in European towns in his time. Then again, even his encounters with segregated Christian groups—on the one hand, Nestorians or Christians of the Church of the East and Christians of the Roman faith, on the other—convey the presence of segregated communities.Footnote 114

Funerary rites

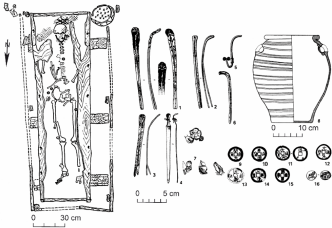

Except for one necropolis outside the north-west city wall of Karakorum, there are no known large cemeteries in the vicinity of the city from the era of the Mongol empire (see Figure 5).Footnote 115 Single and small burial groups have been uncovered mostly through chance finds and during rescue excavations,Footnote 116 but most of these have remained either unpublished or have been presented with incomplete information.

Figure 5. Map of Karakorum and its surroundings with known and at least partially excavated burial places dating to the Mongol period, with 1 Baga Artsat Am;Footnote 120 2 Karakorum city, east;Footnote 121 3 Karakorum city, MDKE east;Footnote 122 4 Karakorum city north;Footnote 123 5 Karakorum city, west;Footnote 124 6 Karakorum, mass grave;Footnote 125 7 Mamuu Tolgoĭ;Footnote 126 8 Moĭltyn Am;Footnote 127 9 Nariĭny Am;Footnote 128 10 Tüvshinshirėėgiĭn Am.Footnote 129 Source: Author.

Generally, Mongol period burials are characterized by inhumation in pit-graves, sometimes in wooden coffins. The surface of the burial site is commonly marked by a layer of small stones obtained in the immediate surroundings. The dead were placed in a supine position, as a rule oriented north–south—although exceptions to the rule can be observed as well—and accompanied by their personal belongings. Some burials are lavishly furnished. However, not all members of the Mongolian society received the kind of burial that could be identified by later generations, let alone centuries later by archaeologists. It is known that the uppermost elite of the ruling clan were buried in secret and it is doubtful whether commoners are even represented in the archaeological record.Footnote 117 The limited information available on burials around Karakorum suggests differently structured burial rites, pointing to various groups that laid down their dead spatially segregated (see Figure 6).Footnote 118 But whether the people buried within these surrounding graves were actually inhabitants of the city or nomads who lived outside the city cannot be known.

Figure 6. Example of a Mongol period burial from Mamuu Tolgoĭ with assemblage. Source: Author modified after Voĭtov, ‘Mogil’niki Karakoruma’, p. 139, Figure 5 and p. 140, Figure 6.

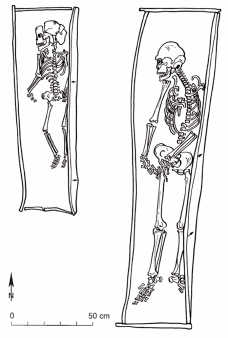

However, Karakorum stands out from all other contemporary settlements in the northern steppes in that there are two cemeteries attributed to Islamic communities. One lies outside the north-west city wall of Karakorum where there is a large area of funerary buildings.Footnote 119 Another cemetery about 8.5 kilometres north-east of Karakorum near Öndör Tolgoĭ is likewise said to represent burials by a Muslim community, but it has not yet been published.Footnote 130

Excavations in the north cemetery of Karakorum between 1978 and 1980 brought to light a central subterranean funerary house with an inhumation burial surrounded by 36 individuals.Footnote 131 While some aspects of the burial style were at first glance not dissimilar from Mongolian traditions—the dead lay mostly in a supine position, oriented roughly north to south—other characteristics pointed to a different community.

Most graves are not marked on the surface. The heads of the deceased were mostly turned to the east, so that they were facing Mecca and bodies were stripped of all personal belongings. Some were possibly buried in a shroud, which fits the custom of a Muslim burial (see Figure 7).Footnote 132 Especially noteworthy is the age profile of the burials: of the 37 human remains identified, 67.6 per cent were infants or children at the time of their death. This seemingly high proportion is well in line with established mortuary rates of these age groups in premodern societies.Footnote 133 Underrepresentation of juveniles in archaeological datasets is a well-known issue,Footnote 134 which is also prevalent in Mongolian records.

Figure 7. Example of Muslim-style burials from the north cemetery of Karakorum, graves 8 (left) and 9 (right). Source: Author modified after Bayar and Voitov, ‘Islamic cemetery’, p. 293, Figure 4.

As already stated, we do not have a comparative dataset from the Orkhon Valley, but a comparison with the Mongol cemetery of Buural Uul, Khongor Sum, Selenge Aĭmag, where 20 burials were excavated from 1980 to 1984, shows a very different mortuary age distribution. From Buural Uul, there are 17 age estimations, only 29.4 per cent of which are represented by juveniles.Footnote 135 If the statistics are not the result of lower mortality rates among infants and children in this Mongolian community, differential preservation, or faulty age estimations, they may be an indicator of how differently the Muslim community treated their dead.

One conclusion to draw from these observations is that different communities in Karakorum buried their dead in different places. This phenomenon is also observed around the city of Timbuktu, Mali, where archaeologist Timothy Insoll identified burials divided ethnically into different cemeteries that mirror the division of residential quarters within the city.Footnote 136 So far, around Karakorum, we cannot observe a shared burial place or the incorporation of different styles within one burial. This segregation along religious, and potentially ethnic, lines could be used to argue against the presence of lived cosmopolitanism, although it should be taken into account that funerary traditions are known to be rather conservative practices in human societies. We also do not know if Muslims of different origins were buried within the same necropolis at Karakorum. Even if analyses of stable isotopes on the human remains might help to approximate their origins in the future, the self-ascribed identity of the individuals would still remain an unresolved question since grave furnishings are missing in these burials.

Lived cosmopolitanism of Karakorum?

What conclusions can we draw from the presented materials with respect to practices of cosmopolitanism at Karakorum? First, Karakorum can be deemed a pragmatic combination of steppe spatial organization realized through building techniques and styles appropriated from conquered regions, principally of China. This blending and appropriating of existing traditions into new ones can therefore be seen as an expression of the lived cosmopolitanism of the uppermost Mongol rulers, foremost Ögödei and Möngke. Most buildings we know from Karakorum are attributed to building programmes from the earlier phases between 1235 and the 1250s. Further examples of lived cosmopolitanism, such as food practices at the court, openness to religious pluralism, and a pluralistic approach to languages, are likewise the result of cultural and political decisions made by the uppermost ruling elite. These examples stem mostly from around the mid-fourteenth century, which attests to the long tradition of lived cosmopolitanism among the Mongol great khans.

As the exploration of the available material from Karakorum shows, the positive identification of cosmopolitan practices among the common people remains, however, a challenge. The current state of knowledge of the material record would suggest a low degree of willingness in engaging with and incorporating different cultural strands. The cited examples stem from the whole settlement sequence of roughly 200 years. A more detailed analysis of individual settlement phases might reveal a more nuanced development of potential cosmopolitan practices over time.

For now, differences in food consumption between the middle of Karakorum and the Buddhist monastery might point to different ethnic preferences for certain meats. Burial places and mortuary practices are another example of ethnically divided religious groups. The description by Rubruck of different quarters segregated along ethnic and professional lines strengthens this impression. Other aspects, such as the issues of volition and agency, also need to be taken into consideration with regard to these findings. As already pointed out, the craftspeople from the middle of Karakorum were captives from far-flung corners of the growing empire and did not voluntarily reside in Karakorum, which is very different to the specialist elite culture at the Mongol court outlined in the introduction. Who decided where these people lived and buried their dead, and how were the decisions made? Were these conscious decisions by different groups, religious, ethnic, professional, or otherwise? Or were they imposed by higher authorities? While textual sources do not openly discuss these questions, Rubruck’s encounters with Christian groups certainly imply that there was room for decision-making by non-elite individuals and possibilities for personal advancement, as the impressive career of the goldsmith Guillaume de Boucher demonstrates.

But even for groups who certainly had more leeway in terms of decision-making, the state of cosmopolitanism is not as clear-cut as one would think. We learn from the Persian inscriptions from Karakorum about endowments and donations by certain people who were well-to-do, but it is unclear how legal ownership and property rights in Karakorum were formulated and connected to the endowments. Both assumedly Chinese city administration personnel and the Persian donors adhered strictly to the legal systems and language of their supposed origins, which does not provide evidence of lived cosmopolitan practices among these groups, even though the acceptance of different languages on monuments within the city can be seen as exceptional and an expression of toleration. Quite the contrary, these findings do not reveal the merging of various population groups into a homogeneous mass, sometimes referred to as the ‘melting-pot’.Footnote 137 Similar observations have been stated in the case of Sarai, a city of the Golden Horde: ‘But Sarai was not a melting pot, exactly, as groups of foreigners tended to live in their own clearly demarcated districts.’Footnote 138 The cities of the Golden Horde could provide helpful material for a comparative case study on steppe cosmopolitanism in future research. The turn to practice theory provides the nexus to identify cosmopolitan practices in the archaeological record. However, as we have seen, it is important to clearly differentiate between population groups and actors within the city, since everyday experiences and practices vary. Simply equating Karakorum as a whole with cosmopolitanism fails to do justice to the rich variation of people in this city as well as to the layered meanings of the term ‘cosmopolitanism’ itself.

Conclusion

There are varied definitions of cosmopolitanism in the scholarship, but the term is most often interpreted as a normative concept that describes a certain mindset of openness towards the ‘other’. The discussion of cosmopolitanism in this article led to a fruitful new approach in archaeological studies, primarily based on material culture, coined ‘lived cosmopolitanism’, suggesting a turn to practice-oriented questions, which is compatible with archaeological approaches. In exploring the archaeological record of Karakorum, this article traced cosmopolitan practices in the cultural fields of spatial organization and architecture, cuisine, religion, and funerary rites. Although cosmopolitan practices are identified in different aspects of human behaviour, we can conclude that there is no such thing as a cosmopolitan Karakorum as a whole. Instead, we need to carefully differentiate between social groups and their individual capacity for decision-making. The Mongol rulers manifested as true cosmopolitans of their time, while among the common people of Karakorum, the communities appear rather segregated.

This article is merely the start of a conversation about cosmopolitan practices. It has therefore focused on selected aspects of the Karakorum society, which would be worthwhile to explore in more depth, e.g. through the incorporation of object life histories. Exploring cosmopolitanism runs the risk of oversimplification in attributing certain objects of the archaeological record to specific ethnicities or other identities, be they gender, religious, or other roles. Instead, findings need to be discussed in the multi-dimensional ways they could have been used in the past.Footnote 139 The approach of object life history entails a holistic view of the life cycle of the artefact in question, from production to distribution and consumption, as a basis for reconstructing object identities or their usage within different contexts, which could reveal instances of lived cosmopolitanism.Footnote 140

Although the evidence so far does not suggest a high degree of lived cosmopolitanism among the inhabitants of Karakorum, posing the question revealed previously un- or under-explored aspects of the inner workings of city life that has conventionally been generalized. It is problematic to simply label the city as cosmopolitan, although individual experiences might vary among different social groups. Even if there might not be a straight answer to whether the city’s inhabitants followed cosmopolitan practices, exploring cosmopolitanism raised important questions which scholarship has, until now, overlooked, such as property rights and individual decision-making processes. It laid bare issues pertaining to the social lives of the population. The scholarship has not always acknowledged the harsh realities in which underrepresented groups in the written sources found themselves. Although the answers to these questions lie outside the scope of this article, the turn towards cosmopolitanism will hopefully encourage further research into these areas.

Acknowledgements

The article was written during the time the author spent as a Feodor-Lynen fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation at the University of Michigan and as part of the project ‘FOR5438: Urban impacts on the Mongolian plateau: Entanglements of economy, city and environment’ funded by the German Research Foundation (project number 468897144). The article profited tremendously from the open discussions within the project ‘Centering the northern frontier: Integrating histories and archaeologies of the Mongol empire’ at the University of Michigan whose members generously provided papers and literature. I am indebted for many fruitful discussions with and suggestions by Jan Bemmann and Bryan K. Miller. Earlier versions were presented during the conference ‘Cosmopolitan pasts of China and the Eurasian world’, LMU Munich, in June 2021 and at the Hebrew University’s ‘Mongol Zoominar’ in February 2022. I thank all participants for their valuable questions and insights.

Competing interests

The author declares none.