Introduction

In this article, I consider the Second World War’s effects on radio infrastructures and listening cultures in South Asia through a detailed analysis of two stations: Radio SEAC and Congress Radio. Radio SEAC was a military radio station based in the crown colony of Ceylon, whose broadcasts targeted British soldiers stationed in Asia during the waning years of the war. The station’s name was the acronym for the Southeast Asia Command (SEAC), but it technically targeted British soldiers in both the Southeast Asia and India military commands. The station housed a powerful and wide-reaching transmitter, which the British government’s War Office had ordered from the Marconi company in 1944 in the hope that providing access to entertaining radio programmes would lift the spirits of British soldiers stationed in the East and help sway the war in Britain’s favour.Footnote 1

In contrast to this powerful, trans-regional imperial radio station, Congress Radio was a makeshift station in Bombay relying on a low-power transmitter that could only reach a few neighbourhoods in the city, run by a small group of young anticolonial activists with little or no broadcasting experience. Frustrated with the censored print media, motivated by Gandhi’s famous call for the British to ‘quit India’, and likely to have been inspired by the growing popularity of Axis radio stations broadcasting in Indian languages, this group of activists took to the airwaves. Congress Radio aired its first broadcast in late August 1942 as the Quit India movement’s uprisings unsettled colonial rule in Bombay and India more generally.Footnote 2 While clearly Radio SEAC and Congress Radio operated on vastly different scales and had rival goals, their political ambitions and staging of technology, this article will demonstrate, were rather similar.

Radio SEAC sought to restore confidence in the empire during a moment of crisis by invoking an old device of imperialism: what Brian Larkin calls the ‘colonial sublime’, the use of ‘technology to represent an overwhelming sense of grandeur and awe in the service of the colonial power’.Footnote 3 Focusing on Nigeria, Larkin argues that British mastery of technology was ‘part of the conceptual promise of colonialism and its self-justification—the freeing of natives from superstitious belief by offering them the universalizing world of science’.Footnote 4 Expanding on Larkin’s findings, in my analysis of Radio SEAC, I demonstrate how the colonial sublime was not only directed at colonized populations, but was also used to try to reassure a dispirited British population (in this case British soldiers) of the empire’s continuing vitality when its demise had become all but certain. Yet, if the colonial sublime was an effort by colonialists to use technology as ‘evidence of the supremacy of European technological civilization’, then the makeshift underground Congress Radio station turned that idea on its head.Footnote 5 The young Bombay-based activists and Quit India movement participants who managed it sought to demonstrate that British colonialists did not have a monopoly on technological mastery. By using technological innovation against colonial rulers and by embracing radio broadcasting against colonial rule, these amateur broadcasters sought to summon what we might call the anticolonial sublime. Madhu Limaye, a writer and anticolonial activist during the Quit India uprisings, alluded to the power of the anticolonial sublime when describing Congress Radio: ‘the broadcasts were indistinct. They could not have damaged the government much. But the Congress Radio was a challenge to its authority and prestige.’Footnote 6

Paying attention to the (anti)colonial sublime also invites us to rethink assumptions about how the medium of radio connects with audiences. As we will see, British administrators tried to re-establish faith in the empire less through the content of Radio SEAC’s programming than through the aura of technological grandeur that administrators hoped the military station’s transmitter, lauded as among the best in the world, would surely generate. Similarly, Congress Radio’s influence had less to do with the actual broadcast content than with the air of insubordination the station’s presence on the airwaves conveyed, regardless of how limited its transmitter’s actual reach was and how few people could tune in. The radio had become a vital technology during the Second World War, critical in both military and civilian contexts, and broadcasting acquired an important symbolic value that went beyond its logistical benefit. To command the airwaves was to command power.Footnote 7 Therefore, in answering Andrea Stanton’s call to study radio’s infrastructures and materiality, this article demonstrates that the materiality of radio also had important communicative power.Footnote 8

For the young anticolonial activists who managed Congress Radio, as for the British War Office that controlled Radio SEAC, ‘the medium was the message’ to borrow Marshall McLuhan’s famous rendering.Footnote 9 The medium and the message converged in the aura that these two stations sought to evoke, even as their aesthetic manifestations of the ‘(anti) colonial sublime’ differed greatly. Congress Radio’s technology was faulty, and its broadcasts were often inaudible. Yet, whereas the colonial sublime required technologies to work efficiently and even smoothly to convey a ‘sense of power’, the anticolonial sublime did not.Footnote 10 Congress Radio broadcasters owned the station’s static-filled and unreliable reception as much as they celebrated their station’s underground, secretive, and rebellious character. Broadcasters encouraged audiences to spread the station’s message via word-of-mouth and actively cultivated an aesthetic of rebelliousness and even illicitness. In contrast, British administrators focused on and celebrated Radio SEAC’s wide-reaching and high-tech powerful transmitter as an example of the British empire’s still unbeatable technological might.

Interestingly, the (anti)colonial sublime also helped build the archive used in this study. As Alejandra Bronfman reminds us, histories of radio, and the media more generally, require a particularly reflexive approach, attentive to the ‘the role of communications technologies as mediators and authors’ of archives.Footnote 11 Studying Radio SEAC and Congress Radio together allows us to fully appreciate how the (anti)colonial sublime helped build the station’s archives and to read these sources critically and reflexively. A fixation with Radio SEAC’s powerful transmitter and various efforts to celebrate and publicize it ensured that this station left behind a rich paper trail. Likewise, British administrators’ reluctance to bequeath the transmitter to the newly independent Ceylonese government after 1948 was well documented. Similarly, in the case of Congress Radio, the colonial government’s extended and well-publicized efforts to shut down the underground radio station and to punish its founders also helped create a sizeable paper trail. The Bombay police transcribed (and translated) nearly all of the station’s broadcasts and collected details about the station’s inner workings and its organizers’ personal lives through investigations and a series of depositions. The trial involving Congress Radio, like most court proceedings against anticolonial activists, was well documented. This imperial paper archive, read alongside the detailed personal account of Usha Mehta, one of Congress Radio’s leading voices and organizers, has made it possible to stitch together Congress Radio’s story.Footnote 12

The stories of Radio SEAC and Congress Radio form part of a larger narrative about radio and the Second World War in South Asia. In 1928, following a discussion of radio and its potential uses in India, the marquess of Linlithgow, serving as viceroy of India, remarked: ‘It cannot be said that broadcasting is, under existing conditions, of immense strategic importance in India.’Footnote 13 As Joselyn Zivin notes, behind his hesitation lay a looming fear that by building up a broadcasting infrastructure, the government ‘might just be creating a mouthpiece for the growing and increasingly vociferous anti-colonial movement’.Footnote 14 The outbreak of the war, however, ultimately forced the administration to finally build that broadcasting infrastructure. Axis radio stations, first from Germany and later Japan, filled the Indian airwaves. Largely in response to the growing popularity of Axis radio broadcasts, the British government in India made ‘its first genuine’, albeit ‘belated and haphazard’, attempt to reach the general population through the medium of radio and developed the national network, All India Radio (AIR).Footnote 15

Although the British Government of India did not technically have jurisdiction over Radio SEAC, which was based in the crown colony of Ceylon, Radio SEAC did form part of the British colonial administration’s larger foray into broadcasting during the Second World War. Similarly, while Congress Radio was by no means an Axis radio station, the station bore an important relationship to German and Japanese stations broadcasting in Indian languages during the war.Footnote 16 As I further describe in this article, Congress Radio, like Axis radio stations, embraced the notion of radio as a medium of defiance that could bypass colonial censorship of the print media. Moreover, like Axis radio stations, Congress Radio broadcasters encouraged its audiences to spread the station’s message via word-of-mouth by talking to family and friends about what they had heard on the radio.

By studying Radio SEAC and Congress Radio together as wartime radio stations, this article, like the special issue as whole, demonstrates that the Second World War was a transformational event in the subcontinent’s history that had long-lasting effects on broadcasting infrastructures and listening cultures.Footnote 17 This article presents Quit India not only as turning point in the anticolonial movement, but also as a Second World War ‘moment’ related to the pressures and changes of the global war. In this way, when read together, the stories of Radio SEAC and Congress Radio show how, during the Second World War, the medium of radio simultaneously served and contested the colonial state. Moreover, the global war set the stage for a continuing rivalry between state-sponsored radio networks and rival stations, whose broadcasters used radio technology to consciously challenge state agendas in the post-independence period in South Asia. By analysing these two radio projects, which operated on very different scales, alongside one another—one hoping to reinvigorate the empire and the other hoping to discredit it—we can begin to trace radio’s important role during a turning point in the region’s history.

Radio SEAC and the colonial sublime

The story of Radio SEAC begins with a series of newspaper reports about the declining morale of British soldiers stationed in Asia. Among them was an article in the Sunday Pictorial about the poor facilities available to soldiers stationed in Asia compared to soldiers in Europe. According to Eric Hitchcock, the Sunday Pictorial reported that medical facilities for British soldiers in Asia were ‘starved of personnel and out of date in [their] equipment’ and soldiers lacked access to the simplest of pleasures: beer, cigarettes, and radio.Footnote 18 Not long after the article’s publication, Leo Amery, a cabinet minister and secretary of state for India, sent his undersecretary, Earl Munster, to conduct an official investigation into the matter. Munster’s formal report, following several weeks of interviews, was not all that different from the newspaper’s conclusions. British soldiers in South and Southeast Asia, he explained, clearly suffered from low morale. The situation, he insisted, was critical and urgent. His recommendations included improving medical facilities, increasing soldiers’ beer and cigarette rations, and ensuring they had access to better radio programmes. The BBC troops’ broadcasts, he reported, were mostly inaudible throughout Asia. While All India Radio did produce various programmes for soldiers, these aired only for a few hours a week and most programmes catered to the tastes of Indian soldiers. British forces in South and Southeast Asia, Munster concluded, needed their own radio service.Footnote 19

The War Office took Munster’s recommendations seriously, particularly those related to radio.Footnote 20 In November of 1944, when the war’s end still felt far away, the office proposed a bold and ambitious plan: setting up a radio transmitter in India powerful enough to reach all British soldiers wherever the war in the East would take them. The transmitter cost more than a quarter of a million pounds, not including transportation, maintenance, and programming expenses.Footnote 21 Given the financial difficulties faced by the War Office and the British government more generally, this was no small investment. Yet, behind the War Office’s interest in this grand project and its state-of-the-art 100kw shortwave transmitter—about as powerful as possible back then—was a desire to demonstrate mastery over what had become the most important form of media communication during the global war. In the summer of 1945, the War Office gave the go-ahead to the Marconi Company to begin assemblage of the transmitter and to make arrangements to ship the equipment to Asia.Footnote 22

Louis Mountbatten’s Radio SEAC

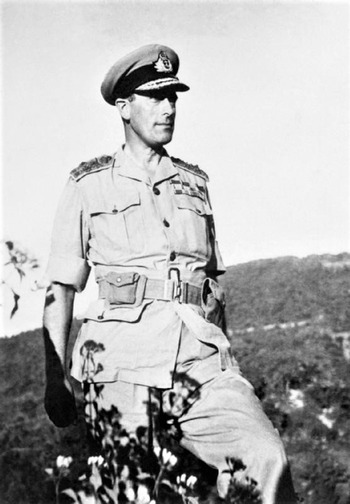

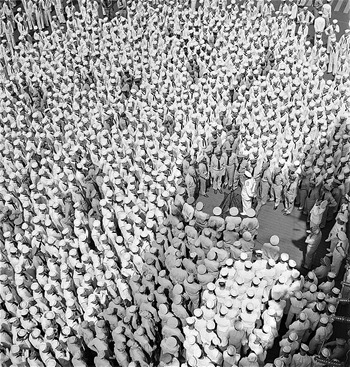

One individual, famous for his media-savviness and for his propensity for showmanship, took an immediate interest in the large-scale radio project: Louis Mountbatten, the supreme commander of the Southeast Asia Command (SEAC) (see Figures 1 and 2). In present-day India and Pakistan, Mountbatten is known as the last viceroy of India, but for our purposes, it was his prior, lesser-known military appointment that proved most influential.Footnote 23

Figure 1. Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten in Arakan, Burma, February 1944.

Figure 2. Louis Mountbatten speaking to the officers and men of USS Saratoga at Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), 30 April 1944.

In August 1943, following a series of Japanese advances in Southeast Asia, Churchill and Roosevelt formed SEAC to coordinate Allied air, sea, and land operations in the Southeast Asia Theatre. Mountbatten’s biographer, Philip Ziegler, writes that, at the time, nobody seemed to know exactly what the supreme commander’s duties and responsibilities would entail.Footnote 24 Mountbatten, however, considered public relations to be a crucial part of his role. He met with troops often, helped inaugurate a troops newspaper, and took every opportunity to publicize his command.Footnote 25 As supreme commander, Mountbatten technically served both American and British troops, but American soldiers complained that Mountbatten cared only for British troops and that SEAC might as well stand for ‘Save England’s Asian Colonies’.Footnote 26 Ironically, this name also aptly describes the purpose that Radio SEAC would later serve.

It was no secret that Mountbatten had a fondness for media and publicity. While in charge of the Royal Navy, he had contributed to the making of the film In Which We Serve (Noël Coward, David Lean, 1942), which was loosely based on the Royal Navy’s HMS Kelly, which Mountbatten had commanded (see Figure 3).Footnote 27 In his diary, Archibald Wavell, both an army commander and the Indian viceroy who preceded Mountbatten, described a conversation with him. When Wavell explained that he had not seen a particular film because he was ‘not musical’, Mountbatten offered a brash retort: ‘You don’t need to be musical to enjoy musical films, with just cheerful songs and dancing.’ Wavell wrote that that conversation had left him feeling like a ‘cheerless killjoy’.Footnote 28 In addition to cinema and music, Mountbatten’s interest in technology and radio is noted in other sources. While working in the Royal Navy, Mountbatten had trained as a wireless technician and even published a manual about wireless technology. In his diary, Mountbatten also noted that he was fascinated with the nawab of Rampur’s extensive collection of radios.Footnote 29

Figure 3. Poster of In Which We Serve.

Given this prior interest in media—and radio specifically—it is unlikely to have come as a surprise to anyone that when Mountbatten learned about the War Office’s ambitious radio venture, he could not help wanting to take it over. One Radio SEAC engineer pointed out that from the very beginning, the whole project had a rather ‘Mountbatten style about it’ because it was a ‘bold, ambitious undertaking costing a lot of money’.Footnote 30 Radio SEAC, however, had a ‘Mountbatten style’ for another reason: Mountbatten, perhaps more than any other high-ranking British official, was interested in the ‘performance of empire’, and in particular in performing empire before the British public. Two years after the end of the war, when Mountbatten oversaw the British departure from India as viceroy of India, he personally choreographed the British media coverage of the event and was remarkably successful in presenting the loss of Britain’s most important colony as a moment of imperial celebration.Footnote 31 Radio SEAC, like the decolonization ceremony Mountbatten later hosted, can be read as a quixotic attempt to revive faith in Britain’s imperial project at the very moment its end was all but certain.

In the original report on British soldiers’ morale, the undersecretary Earl Munster had assumed the new radio station for British soldiers would be based in Delhi and would make use of All India Radio’s brand-new facilities, which the British government had expanded, largely in response to wartime needs.Footnote 32 Mountbatten, however, had just moved SEAC’s headquarters from India to Ceylon, and he lobbied hard to convince the War Office to ship the Marconi transmitter to the island.

Mountbatten’s move to Ceylon had not been without controversy. Some believed that the supreme commander, who was related to the royal family, had moved his staff to the island so that he could enjoy a more regal lifestyle. After all, Mountbatten’s office was in Kandy’s botanical gardens, which were famous for their exquisite beauty. Documents, however, reveal that the shift to Ceylon was more likely to have been motivated by Mountbatten’s desire to sidestep the bureaucracy of the British Government of India and to evade the pressures of the growing Indian anticolonial movement than by Kandy’s luxurious gardens.Footnote 33 Ceylon was a crown colony governed closely from London and had not witnessed mass opposition to colonial rule in the same manner as India.

In response to Mountbatten’s requests, the War Office compared the pros and cons of the two locations. Echoing Mountbatten, the committee pointed out that in Ceylon the War Office would have more control over the station as it would not have to defer decisions to the Government of India, but noted that from a financial point of view, Delhi was the better choice because the radio station there already had studios and trained personnel. However, the deciding factor seems to have been related to the transmitter’s reach. The committee noted that in Colombo the Marconi transmitter would be likely to enjoy wider reach because of the specific atmospheric conditions there.

Mountbatten named the military station Radio SEAC, after the initials of his own regime, but the station technically catered to soldiers in both the SEAC and India commands. In a letter, Mountbatten explained to the concerned commander-in-chief of India, Claude Auchinleck, that the name had been selected because it was ‘short’ and ‘easily pronounceable’ and reassured Auchinleck that the new military radio would not give preference to soldiers in SEAC over India Command soldiers. Radio SEAC’s broadcasts, Mountbatten explained, would begin with the following announcement: ‘This is the forces broadcasting service, Radio SEAC, broadcasting in India and Southeast Asia’.Footnote 34 It is likely that Auchinleck was not satisfied with Mountbatten’s explanation, but he ultimately dropped the matter, at least in official correspondence.

Radio SEAC goes on the air

Unaware of the war’s nearing end, the War Office made plans to inaugurate the new military station in Ceylon in April 1945.Footnote 35 A team of ten BBC radio engineers reached Ceylon that summer to assemble and provide maintenance to the famed 100KW transmitter as Mountbatten’s SEAC staff busied themselves preparing new studios and offices and training broadcasting staff. But a dock strike and other war-related hindrances kept setting back the date of the transmitter’s arrival and delaying the station’s inauguration.Footnote 36 Eager to start airing radio programmes for British soldiers, Radio SEAC staff began broadcasting on low power transmitters.Footnote 37 Since the Marconi transmitter was yet to arrive, there could be no grand unveiling ceremony. As Larkin notes, unveiling and inauguration ceremonies were important symbolic events when the idea of technology and infrastructure as colonial spectacle could be felt most powerfully.Footnote 38 For Mountbatten, the inauguration of a large transmitter that had been shipped directly from Britain would have been an affirmation not only of Radio SEAC’s technological might, but also of his own influence as the supreme commander of SEAC.

Without the Marconi-built transmitter to boast about, the station’s launch did not make much of splash. Its programming was, if anything, characterized by its ordinariness. As the War Office had originally planned, news and music programmes took up the majority of the station’s airtime. Radio SEAC prepared a few local news programmes that specifically addressed news items related to the SEAC and India commands, but BBC news relays made up the majority of the station’s news coverage.Footnote 39 Music programmes were locally produced, and these consisted mostly of music rotations featuring contemporary songs popular in Britain at the time.Footnote 40 While not particularly unique, it appears that these music rotations did quickly gain a robust following among soldiers. It is telling, for example, that the station’s magazine, SEAC Forces Radio Times, regularly printed excerpts from listeners’ letters and broadcasters’ responses.Footnote 41

On one occasion, Victor Poole, the host of Heard Memories, explained to his fans that he was receiving too many requests for the film song ‘Warsaw Concerto’.Footnote 42 Poole noted that as much as he wanted to satisfy his listeners’ wishes, he could not play just this one song for the entire duration of the programme.Footnote 43 Poole’s comments and other notes by broadcasters and listeners published in this magazine indicate that Radio SEAC, even in its diminished form and relying on low-power transmitters, helped to build a sense of community among soldiers.Footnote 44

While sources suggest soldiers enthusiastically participated in music request programmes, the station fell short of accomplishing the colonial sublime in the ways that the War Office and Mountbatten himself had probably hoped for.Footnote 45 Without the powerful, awe-inspiring transmitter, Radio SEAC was a rather mundane military radio station producing routine programmes at the tail end of the global war. Still, this failure is representative of the ways in which the colonial sublime functioned (or failed to function) in colonial settings. As Larkin notes, ‘the British made totems out of technology and placed them centre stage in society’, but as technologies malfunctioned or became ordinary, they failed to convey the same ‘sense of power—the feeling of submission and prostration’. One of the characteristics of the colonial sublime, Larkin then argues, was that it was necessarily temporary and ultimately short-lived.Footnote 46 Radio SEAC, however, was unique in that its aura faded before it had even begun to shine.

The transmitter’s arrival and transfer of ownership

In May of 1946 the much-awaited Marconi transmitter finally aired its first broadcast from Ceylon. By then, the war had been over for more than a year and Mountbatten was already making plans to leave the island permanently.Footnote 47 But there were still British officers stationed in Asia and Radio SEAC continued to air programmes for their entertainment.Footnote 48 Within weeks of the transmitter’s inauguration, soldiers and civilians in South and Southeast Asia remarked on its extraordinarily clear and static-free transmission and its widespread reception, which reached significantly further than anticipated. Radio listeners in the Middle East, parts of Africa and Europe, and even some wireless enthusiasts in the United States reported hearing its transmissions and sent detailed reception reports to Radio SEAC staff in Ceylon.Footnote 49 The War Office also learned that an increasing number of civilians were now tuning into Radio SEAC, enticed, it appears, by their static-free music programmes.Footnote 50 Under different circumstances, this would have been the perfect opportunity to celebrate the transmitter’s unprecedented reach and to invoke the colonial sublime. However, with most soldiers returning home and with the massive communal violence that followed Britain’s retreat from India and Mountbatten’s departure, there was no longer space to celebrate the awe of imperial technology.

The question facing British officials now was a different one: what to do with the transmitter, which was too big to disassemble and ship back to Britain.Footnote 51 Some suggested the War Office and the BBC should coordinate and launch a new Asia-wide service to promote the commonwealth. One officer explained that the station could help Britain remain a ‘forefront voice’ in the ‘two new dominions’ [meaning India and Pakistan].Footnote 52 Ceylonese leaders, however, quickly deflated these lofty dreams. In February of 1948, British Ceylon gained independence and the country’s first prime minister, Don Stephen Senanayake, made it clear that the new government would not allow their former colonial leaders to run a military radio station on their soil.Footnote 53 British officers went into a mild state of panic when they discovered Ceylon officials were already making plans to start a commercial station using SEAC’s transmitter.Footnote 54 One worried British official explained that American businesses could take advantage and advertise their products on the airwaves ‘with serious consequences to United Kingdom markets’.Footnote 55 Even more dangerously, commercial broadcasting ‘“across frontiers”Footnote 56 could have unexpected political consequences’.Footnote 57 The message here seems to be that if Britain was not able to take advantage of the transmitter’s sublime powers, letting others do so would be unwise.

In the end, Prime Minister Senanayake made two concessions that helped ease British officials’ worries. He promised to give preference to British and commonwealth clients in the new commercial service and agreed to let BBC staff use the transmitter to relay news to the remaining British troops in Asia for a few hours a day for a period of two more years. In March 1949, the former British military transmitter aired its first broadcast as Radio Ceylon.Footnote 58

Immediately after the transfer of ownership, the Ceylonese began commercial broadcasting to India and Pakistan. Within less than a decade the Hindi-language branch of Radio Ceylon’s commercial service had gained unprecedented popularity in India and Pakistan through its rather creative Hindi film-song programmes, including the immensely popular Binaca Geetmala radio programme.Footnote 59 Scholars have now begun to pay attention to Radio Ceylon’s pivotal role in shaping India and Pakistan’s popular cultures, and in particular in shaping an aural cinematic culture across borders. Largely absent from this story, however, is how British administrators’ desire to invoke the colonial sublime in the midst of a global war made Radio Ceylon’s later rise possible.Footnote 60

Radio SEAC, a massive imperial and trans-regional project relying on a powerful transmitter, was by all accounts an example of what David Arnold calls ‘big technology’ which, like railroads and telegraphs, scholars have long argued was crucial to the exercise of British power in India.Footnote 61 Distinguishing between ‘large’ and ‘small’ technologies, Arnold studies how ‘small’ and ‘everyday’ machines—bicycles, rice mills, sewing machines, and typewriters—that originated in Europe and North America became objects of everyday use in India. Arnold demonstrates how these ‘small technologies’, much neglected by scholars, reshaped the ‘politics of colonial rule and Indian nationhood’.Footnote 62

Yet, the distinction between ‘small’ and ‘big’ technologies can also obscure the ways in which technologies of very different scales are intrinsically connected within a larger colonial regime and might have more in common than is initially apparent. While Radio SEAC and Congress Radio were different in scale, they had rather similar, if rival, political ambitions. Radio SEAC sought to restore pride and faith in the British empire by invoking the colonial sublime. Congress Radio, in contrast, sought to bring down the empire by invoking the anticolonial sublime. Studying these ‘big’ and ‘small’ radio stations alongside one another enables us to gain a deeper understanding of the role of radio in a colonial regime during the Second World War. To tell the story of Congress Radio, however, we must return to a turning point in the global war—to the summer of 1942, when Japan’s string of victories began to chip away at the British empire’s ‘illusion of permanence’, signalling to many in India the beginning of the end of colonial rule.Footnote 63

Underground Congress Radio and the anticolonial sublime

On 8 August 1942, as the war reached India’s doorstep, Gandhi delivered a speech in Bombay demanding that the British ‘quit India’ once and for all. Within hours of this speech, the British government had arrested Gandhi and many Indian National Congress leaders. With many prominent Congress politicians behind bars, local activists led what became known as the Quit India movement as protestors throughout India took to the streets, burned government offices and property, and targeted British administrators.Footnote 64 A group of college-age and Bombay-based friends, inspired by Gandhi’s call to action, came up with a bold plan: to set up an underground anticolonial radio station. The station, they surmised, would air news of the current uprisings as they were developing throughout India, bypassing British censorship of print media, and inspiring more to join the call for an end to colonial rule.

The group’s interest in radio was born ‘out of thin air’, but in the literal rather than the figurative sense. It is likely that the activists were inspired by the growing presence of Indian-language Axis radio broadcasts from Germany and Japan, whose popularity increased during Quit India. The Indian anticolonial leader Subhas Chandra Bose, who had sided with the Axis powers and fled to Germany, made his first radio broadcast in the days following the fall of Singapore and continued to broadcast during the Quit India movement.Footnote 65 Congress Radio joined a larger soundscape where Axis-funded broadcasts dominated, and inevitably listeners associated (and sometimes confused) Congress Radio for an Axis-supporting station.

The four leading organizers of Congress Radio were Usha Mehta, Vithaldas Madhavji (V. M.) Khakar,Footnote 66 Vithaldas Kanthadabhai (V. K.) Jhaveri, and Chadrakant Babubhai (C. B.) Jhaveri. In their twenties, they all seem to have come from relatively well-off families. None were well-known activists or held leading positions in the Indian National Congress or any other anticolonial organization and none were trained broadcasters or had any significant experience with radio broadcasting.Footnote 67

Usha Mehta, a 22-year-old student, took a leading role in the project. In a typically patriarchal slight, the judge who later tried Congress Radio organizers described Mehta, the only woman in the group, as ‘a lieutenant’ of her male comrades. Evidence, however, shows that Mehta’s part in the project was vital. She was one of very few Indian women on the airwaves during the war, and her voice helped the station garner attention. Prior to her work with Congress Radio, Mehta had been a passionate Gandhi supporter and had worn khadi in protest against British economic policies but had avoided large public demonstrations as she felt uncomfortable being in the public eye. During the Quit India movement, however, the young Mehta shed her reticence as she quite literally found her voice.Footnote 68 Mehta’s presence on the airwaves contributed to an aesthetic of rebelliousness that was a crucial aspect of the station’s identity and message. As Christine Ehrick explains ‘the simple act of an identifiably female voice going out over the airwaves’ could challenge the traditional norms. Mehta’s voice was heard ‘louder’ precisely because listeners were accustomed to male-dominated soundscapes.Footnote 69 It is noteworthy, for example, that the police transcripts stated ‘female voice’ in transcripts where Mehta read broadcasts.Footnote 70

Mehta’s friend, V. M. Khakar, whom court documents describe as a ‘Gujarati, aged 20 years, and a native of the District of Una in Junagad’, managed to secure funds for the project. It was he who made initial contact with the more prominent underground Congress leaders who supported the radio station, both financially and logistically. Khakar played a prominent role in the station and ultimately received the harshest sentence for his work.

The third member of the group, V. K. Jhaveri, described in court documents as a ‘Gujarati aged about 28 years and native of Bhavnagar’, was the only one of the group whose anticolonial activities had been known to the police prior to his work with Congress Radio. Jhaveri was connected to elite members of Bombay’s merchant community.Footnote 71 His uncle was the owner of Messrs Narandas Bhawan, a leading jewellery store in Bombay. According to the court’s findings, Jhaveri had been in a business partnership with his uncle, but it had fallen apart because of the young man’s activism. His handwriting appeared on confiscated gramophone records and, according to Mehta, he had helped to arrange for locations where the group could record their programmes before transmitting them on the airwaves.Footnote 72 C. B. Jhaveri, whom court documents described as a ‘Gujarati aged about 23 years and a native of Bombay’, joined the enterprise later. He played a small role in the station’s planning but was present in the transmitter room with Usha Mehta when the police raided the station.Footnote 73

For all technical-related matters, the four young activists relied on Nariman Abarbad Printer, a trained technician and the former principal of the Bombay Technical Institute in Byculla. Two years prior to the outbreak of the war, Printer had travelled to England with five of his students to complete a training course in radio engineering.Footnote 74 After returning to India, Printer secured a licence for amateur broadcasting and purchased parts for assembling a transmitter. Following the outbreak of the war and as part of a larger effort to curtail radio broadcasting and ensure that the medium of radio did not become a vehicle of anticolonial resistance, the British Government of India cancelled all amateur transmitter licences and required all owners to surrender their equipment to the government. Printer dismantled his own transmitter, but secretly kept the parts at his private residence. He later used this equipment to build Congress Radio’s transmitter.Footnote 75

Printer and Khakar had an ongoing business relationship that pre-dated Congress Radio. Khakar had tried to promote Printer’s various inventions, including a mechanism for running motors on kerosene.Footnote 76 According to the court findings, unlike all other Congress Radio organizers, Printer joined the group purely for financial reasons. Printer’s lack of commitment to the anticolonial cause was discussed in detail during trial and, as we will soon see, this discussion provided an opportunity for the other broadcasters to celebrate and publicize their patriotism.Footnote 77

There were several other individuals who were involved in the radio station, but who were not tried in court. A man named Ravindra Ajitrai (R. A.) Mehta (his relationship to Usha Mehta is unclear) was involved in the station from the very beginning. R. A. Mehta knew Printer and Khakar well and had participated in the station’s initial planning. He also procured and rented the flats where the transmitter was located using a false name. R. A. Mehta, however, collaborated with the police, it appears, probably in exchange for immunity, and he was not tried in court. Sucheta Kripalani, an anticolonial activist who decades later became the first woman chief minister, helped prepare news bulletins for the station. Thakur was a technician who assisted Printer and was arrested but not tried with the group. Other names that appear in the court case include Mirza, the young man who had helped Printer with technical transmitter-related matters; the writer and film director Khawja Ahmad (K. A.) Abbas; the activist Moinuddin Harris; and a ‘Parsi lady’ later identified as Commie Dastur.Footnote 78

Nanak G. Motwane also played an important role in the station. He was the director of Chicago Radio and Telephone Co. Ltd, which was Bombay’s largest wireless dealer at the time.Footnote 79 Motwane had helped supply parts for the transmitter and arranged for the filming of the All India Congress Committee’s famous August Quit India declaration, which was later transposed into records and aired on Congress Radio.Footnote 80 While Motwane was not one of the main figures, he clearly supported the station and was tried in court alongside Congress Radio’s four main organizers.Footnote 81

Ram Manohar Lohia, an established socialist Congressman, also supported the station and played an important, if behind-the-scenes, role. After his release from prison in 1941, Lohia went underground, but continued to provide financial and logistical support to various Quit India initiatives, among them Congress Radio.Footnote 82 Achyut Patwardhan, an Indian socialist, also penned some of Congress Radio talks and, like Lohia, contributed to the logistics of setting up the station.Footnote 83

Lohia and Patwardhan’s involvement in the station also helps us assess Congress Radio’s complicated relationship to the Indian National Congress (INC), then the leading anticolonial organization. While the station bore the Congress name, none of the four main figures held leading positions in the organization. Mehta noted the station’s organizers knew that they could not possibly represent the organization. Two actions, however, ensured that the station did take on a representative role. Two weeks after the station went on the air, the All India Congress Committee’s (AICC) Bulletin announced the station’s inauguration and recommended that their subscribers tune in. It is likely that many read this announcement as the Congress’s official endorsement of the station. It is also worth noting that the announcement prompted the Bombay’s police investigation, which ultimately culminated in the raid on the station. Second, Congress Radio regularly broadcast recordings and readings of speeches by the All India Congress Committee members, including Gandhi’s own speeches. These broadcasts must have surely encouraged listeners to ‘hear’ the station as an official messenger of the Indian National Congress.

That these young and mostly unknown activists and first-time broadcasters suddenly became the official voice of the most powerful anticolonial organization is rather telling of the political dynamics of the Quit India movement. As Srinath Raghavan has argued, ‘Congress leadership’ was ‘forced to cool its heels in prison for the remainder of the war’, enabling other actors previously on the fringes of the anticolonial movement to ‘mobilize their own base of support’.Footnote 84 Congress Radio is yet one more example of how local and lesser-known anticolonial groups took on leading roles in the uprising.

Congress Radio, however, was neither the first nor the only attempt to start an underground radio station, but rather one of many to bring the anticolonial message to the airwaves via underground makeshift radio transmitters in India.Footnote 85 In fact, there is evidence that during Quit India there were at least three other makeshift underground anticolonial radio stations located in Calcutta, Ahmedabad, and Pune. None of these other local radio stations became as well-known as the Bombay-based Congress Radio, in part because, as I further explore in this article, the police raid, the broadcasters’ arrest, and the subsequent court case helped publicize Congress Radio and turn these virtually unknown young revolutionaries into protagonists of the anticolonial cause.Footnote 86

Congress Radio’s organizers began this project in the summer of 1942 with a rather ambitious goal. Their initial plan was to set up a network of underground stations throughout India, ensuring that if the government were to shut down one transmitter, as it effectively did, another transmitter would be ready to replace it.Footnote 87 In the end, however, setting up a single radio station with a single low-power transmitter turned out to be a complicated and risky enough undertaking. In marked contrast with Radio SEAC, which the British government had to leave behind after its departure from Ceylon, Congress Radio changed premises several times during the months it was on the air to avoid being caught by the police (see Figure 4).Footnote 88 Each time, broadcasters had to procure a new safe location, move all their broadcasting equipment, and set up the transmitter. To not raise suspicion in the streets, the group hid the equipment in suitcases and pretended to be a family moving apartments and going about their ordinary lives. Once installed in a new place, broadcasters had to be extra careful. In her personal account, Mehta notes she stopped wearing khadi saris while working for Congress Radio to avoid bringing unwanted attention to herself and her colleagues.Footnote 89

Figure 4. List of locations of Congress Radio in Bombay.

Congress Radio’s secrecy is particularly interesting when read against the experience of Radio SEAC. For the military radio station, publicity about the station’s physical structure—the studios, the transmitter, and so on—was crucial for evoking the colonial sublime. In contrast, for Congress Radio, secrecy about the station’s whereabouts was necessary for the station’s very survival, even as it remained important for people to know about the station’s presence on the airwaves. While urging listeners to ‘talk of’ the station’s broadcasts and to spread the word, broadcasters also pleaded: ‘Never talk of the persons behind the stations.’Footnote 90

Broadcasters’ elaborate efforts to keep the Congress Radio running also point to the local nature of the station. Even as Congress Radio broadcasters presented themselves as an India-wide station, the reality is that they relied on local networks to find places to set up their station, to record the material they later would broadcast, and to escape the Bombay police’s constant vigilance. In contrast to Radio SEAC’s trans-regional network, which included BBC-trained engineers and broadcasters and collaborations with the BBC and with All India Radio’s Delhi-based staff, Congress Radio was a largely Bombay-based Quit India effort. Dr A. Dastur, a university professor who was in his early twenties during the Quit India movement, explained: ‘This innovation [Congress Radio] was of great significance’ and is an example ‘of the manner and different ways in which Bombay’s young people and students responded’.Footnote 91

Congress Radio’s broadcast content

Congress Radio broadcasts always began with the following phrase: ‘This is Congress Radio calling on 42.34 meters from somewhere in India’, followed by a musical rendition of the Urdu language poet Muhammed Iqbal’s poem ‘Sare Jahan Se Achcha Hindustan Humara’ (Our India is the best in the world). Programming closed with a musical rendition of the Bengali poem ‘Vande Mataram’ (Mother, I praise you).Footnote 92 The choice of these two songs was highly symbolic. The first poem was an anthem to the idea of Hindustan as a shared homeland for people of all faiths penned by a renowned Urdu and Persian language poet. In choosing this poem, Congress Radio was making clear the station’s commitment to the idea of Hindustan as a religiously inclusive homeland and rejecting any version of Indian nationalism that sought to exclude Muslims.Footnote 93 The second was a poem by the Bengali writer Bankim Chandra that was adopted by the Congress Working Committee as a national song in 1937.Footnote 94 These two compositions became essential aspects of the station’s identity and aesthetics—signature tunes by which listeners could recognize the station. On various occasions, Congress Radio broadcasters reminded listeners that even if the reception was unreliable and they could not make out the broadcasts, they could always tell Congress Radio apart from other stations by its opening and closing tunes.Footnote 95

Congress Radio’s primary broadcast language was Hindustani. In later months, the station also added English translations of broadcasts, but Hindustani remained the main broadcast language of the station. It is particularly interesting that both Khakar and Usha Metha took Hindustani lessons before joining Congress Radio,Footnote 96 but not surprising given Gandhi’s and the Congress’s support of Hindustani as a national language. In its choice of language Congress Radio also echoed Axis radio’s various broadcasts. As I have argued elsewhere, language was a crucial component of Axis radio’s presence in India. In fact, the perceived success of the use of Hindustani by German and Japanese radio pushed the British administration to scramble, ultimately unsuccessfully, for an effective language(s) to address Indian audiences on the airwaves.Footnote 97

Congress Radio’s programming consisted of three main items: recordings of AICC speeches, political talks, and Quit India news updates. The AICC speeches that Congress Radio broadcast appear to have included both original recordings featuring Congressmen’s actual voices as well as transcripts of speeches read by Congress Radio broadcasters. For example, Congress Radio aired Gandhi’s official appeal to Indian soldiers, where he acknowledged the difficult position soldiers found themselves in and noted that while he did not expect them to defect, they should refuse to carry out orders to kill their countrymen.Footnote 98 Congress Radio also aired Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel’s speech following the ‘Quit India’ declaration and an original recording of Maulana Azad’s speech.Footnote 99 If the British government had succeeded in silencing the leadership of Congress by arresting its main leaders, Congress Radio had quite literally given the voice back to the anticolonial organization by successfully bringing these leaders’ voices to the airwaves.

In addition to AICC’s speeches, Congress Radio also aired its own original talks. According to court documents and to Usha Mehta’s own account, Lohia penned many of these.Footnote 100 They focused on workers’ rights and clearly aligned the station with the party’s left-leaning wing, to which Lohia belonged. One speech, for example, noted: ‘Revolution for freedom is the revolution for the poor. Free India will be of the workers and peasants’.Footnote 101 Some talks specifically addressed workers, urging them to participate in the strikes: ‘Remember whenever you touch any part of the machine in the factory you dip your hands in the blood of your countrymen and you strengthen the slavery of your motherland’.Footnote 102 These talks had an unpolished and improvised quality. In this way, Congress Radio differed from the government-run All India Radio that employed a sober tone and was closer aesthetically to the less polished, more provocative Axis radio stations broadcasting to India.

If the role of workers in the anticolonial movement was the leading topic of Congress Radio’s talks, the colonial government’s censorship of news and the print media followed close behind. After the outbreak of the war in 1939, the colonial government re-enacted the Defence of India Rules Act of 1915, which gave British authorities at all levels of government almost unlimited ability to censor the print media.Footnote 103 During the first years of the war, government officials opted for what the historian Devika Sethi describes as less blatant methods of control, but as the war turned in Japan’s favour, the government embraced more aggressive censorship methods.Footnote 104 During Quit India, the British government enforced even greater levels of censorship and not only clamped down on pro-Axis publications, but also actively tried to stop the flow of information and news about the rebellion between provinces.Footnote 105 Congress Radio put the blame on newspaper editors, arguing that they collaborated with the British and purposefully hid the truth from readers. In reality, many editors actively protested against the government’s censorship tactics, but in condemning print media, Congress Radio accomplished something else: it presented radio as a means of defiance against British imperialism.Footnote 106 ‘Radio,’ explained one Congress Radio broadcaster on the airwaves, ‘is the only place where you can find uncensored news.’Footnote 107

Finally, news updates about Quit India constituted the third major item on Congress Radio. These broadcasts consisted of new bulletins that listed uprisings in various cities. In interviews, Mehta expressed pride in noting that her station was the first to report on the developments in the village of Chimur in Maharashtra during Quit India. Following uprisings in Chimur that targeted government workers and facilities, the British government sent the army to the village. These soldiers, Congress Radio reported, not only beat men who had participated in the uprisings, but also beat and even raped village women. We know little about Congress Radio’s news sources. Mehta noted that Lohia received news directly from Quit India organizers, who then passed it on to Congress Radio broadcasters, but does not provide details about original sources.Footnote 108 A British investigator, in contrast, concluded that Congress Radio broadcasters reproduced news about Quit India that was first aired on Axis radio stations.Footnote 109 Neither party provides enough evidence to reach a firm conclusion about Congress radio news sources.

A close reading of transcripts, however, reveals that Congress Radio undeniably echoed some of Axis radio’s leading themes, even if it never voiced support for Axis countries. It is rather telling, for example, that Usha Mehta referred to All India Radio as ‘Anti-India Radio’, a term Subhas Chandra Bose used repeatedly in radio broadcasts.Footnote 110 The theme of blood was also a staple of both Axis radio, including Bose’s Azad Hind Radio(s), and the Bombay-based Congress Radio. While pushing a socialist message, one Congress Radio broadcaster noted: ‘The blood of crores of Indian workers and peasants would not be sucked by the capitalists.’Footnote 111 When criticizing imperial rule, Congress Radio too made references to blood: ‘Some day this savage story of brutal repression will be written in a letter of blood by Indian martyrs.’Footnote 112 Like Axis radio stations, Congress Radio emphasized British mistreatment of Indian women and, as mentioned earlier, celebrated radio as a medium of resistance and as way to circumvent British censorship of the news.Footnote 113

It is therefore not surprising that listeners sometimes confused Congress Radio for an Axis radio station. K. A. Abbas notes that during a Communist Party meeting, his comrades discussed the new station on the air and concluded that this Congress Radio had to be another counterfeit station operating from Germany. Abbas, who had assisted Congress Radio broadcasters by reading and recordings news, explained: ‘I was not in a position to contradict them or to say that I had just come from this secret radio station and that it was a stone’s throw away from the Communist Party.’Footnote 114 Abbas’s anecdote nicely shows that Congress Radio broadcasts formed part of a larger soundscape, where the sounds and messages of Axis radio stations dominated.

Listening to Congress Radio

As explained earlier, Congress Radio relied on a low-power transmitter whose reception could be heard within a small radius in the city of Bombay. Yet, even within that small radius, reception remained a constant problem. The Bombay police’s own transcripts of the broadcasts are peppered with complaints about reception and give us a sense of the difficulties listeners are likely to have experienced when tuning in to the stations: ‘Voice indistinct’,Footnote 115 ‘station closed abruptly at 9:40 pm’,Footnote 116 ‘Reception being poor’.Footnote 117

Writing about Algeria in the 1950s, Frantz Fanon explained that fiddling with the receiver to find rebel stations and listening through the static became an act of resistance against French colonial rule.Footnote 118 Congress Radio broadcasters owned their reception problems and fully embraced the idea of fiddling and listening to the static as an act of defiance. Broadcasters asked listeners to have patience and to not ‘switch of the radio’, even if they could not hear Congress Radio clearly.Footnote 119 ‘We are always on the air from 8:45 pm till you hear Vande Mataram. Move between 39 and 43 meters, which at times is necessary’.Footnote 120 The historian Usha Thakkar writes in her account of Congress Radio that broadcasters’ honest ‘acknowledgment of technical difficulties must have ‘endeared people’ to them.Footnote 121 Here I wish to suggest that this acknowledgement did more than ‘endear’ listeners; it helped create an aura of rebelliousness that formed an important part of the station’s identity.

Congress Radio’s reception and static problems are in marked contrast with Radio SEAC, whose extraordinarily clear reception (after the Marconi transmitter’s late arrival) was a source of great pride, and from the very beginning had been crucial to the making of the colonial sublime. What is noteworthy here is that while the colonial sublime required that technologies work efficiently to impart a ‘feeling of submission and prostration’, the anticolonial sublime didn’t require such technological effectiveness.Footnote 122 On the contrary, the faulty reception, the sensational news bulletins, the somewhat unpolished addresses, and, most importantly, the secrecy regarding the station’s whereabouts and the broadcasters’ identities, all helped forge an aesthetic of rebelliousness. As Brian Larkin notes, aesthetics constituted an important aspect of the colonial sublime. Colonial media infrastructures possessed a particular aesthetic that helped associate colonialism with progress and modernity.Footnote 123 Likewise, aesthetics was also important to the anticolonial sublime. Congress Radio broadcasters nurtured an aesthetic of rebelliousness, by owning and even celebrating their station’s illicitness, faulty technology, and unpolished broadcasts, but also by encouraging listeners to carry the station’s message forward via word-of-mouth.

For a variety of reasons, including wartime shortages of receivers, but, more importantly, the British administration’s initial reluctance to invest in radio broadcasting infrastructure, there were few radio receivers in India. According to one survey, there were just 160,000 registered licences in 1943 for a population of approximately 300 million. While these numbers probably undercounted the number of transmitters for a variety of reasons, there can be no doubt that only a tiny and privileged percentage of the population would have had access to radio receivers, even within the city of Bombay.Footnote 124

Elsewhere, I employ the concept of ‘radio resonance’ to account for how conversation, rumour, and gossip can expand the reach of radio broadcasts. Radio resonance, I argue, helps explain ‘how a technology not yet accessible to much of the population’ could have had such an important role in wartime India.Footnote 125 The ‘talk’ about radio broadcasts was central to the medium’s reception and radio’s form—its aurality and ephemerality (once aired, broadcasts could not be accessed again) further encouraged its word-of-mouth transmission.Footnote 126 Like Axis radio stations, Congress Radio encouraged listeners to carry the message forward by talking about what they had heard on the radio. As Usha Mehta notes: ‘Our listeners help us further in broadcasting out news to the people at large’.Footnote 127 On the airwaves, broadcasters urged listeners ‘to talk’ about broadcasts. One broadcaster noted: ‘talk … appeals to different classes of the population’.Footnote 128 The voices of listeners carrying the message forward, the broadcaster explained, alluding to the power of radio resonance, were not auxiliary to the station, they were the voice of Congress Radio. ‘Let the whole country resound with a million voices all trained to talk uniformly by the only voice of truth and freedom in the country, the Congress Radio calling.’Footnote 129

While Congress Radio was certainly not alone in relying on word-of-mouth, the station stands out in that the resonance it created was less about the material being broadcast (even though this remained significant) than about the extraordinary story of how a group of young, largely unknown, anticolonial activists had successfully managed to deploy radio technology against imperial rulers. Congress Radio also stands out in that the station’s message continued to spread after the Bombay police had effectively shut down the station. In fact, it appears to have been most successful at creating radio resonance after its closure through discussions about the police raid and the months-long trial against the station’s organizers. It is also telling that in her retelling of Congress Radio’s story, Thakkar covers the broadcasters’ arrest and their trial before the describing the station’s programming content. In this way she too gives the police raid and the extended trial more importance than the actual content of the broadcasts.Footnote 130

The Bombay police raid

Immediately after the AICC Bulletin announced the station’s inauguration, the police began regularly to monitor Congress Radio broadcasts.Footnote 131 A supervisor addressed in official documents as ‘Inspector Fergusson’ oversaw the police investigation and a police officer addressed as ‘Officer Kokje’ led on-the-ground proceedings. In his efforts to track down the station, Officer Kokje kept a close eye on radio and radio equipment shops throughout Bombay, monitoring their visitors and sales. After interrogating a shop attendant about a recent transmitter part purchase, Kokje was able to track down and question Printer, Congress Radio’s main technician. Printer agreed to collaborate with the police, probably in exchange for immunity.Footnote 132

On 12 November 1942, Printer accompanied Kokje and a few other officers to the flat in Parekh Wadi where the station was then located.Footnote 133 The police barged through the door and arrested C. B. Jhaveri and Mehta, who were operating the transmitter, and confiscated all their equipment. Usha Mehta remembered the raid somewhat romantically. ‘The arrest formalities took nearly three and half hours. When …we finally step out we found that there were policemen waiting for us at each and every step all the way down.’ She remembered telling her comrade: ‘Today we are getting a Guard of Honour—and that too from the rifled policemen.’Footnote 134

The following day, the police arrested Khakar, V. K. Jhaveri, and Motwane, the owner of the radio shop where Printer had purchased equipment, at their private homes and work offices. The radio station’s dramatic raid was covered in some newspapers. But these publications, probably in compliance with censorship rules, downplayed the broadcasters’ anticolonial activities, focusing instead on the raid and the police’s findings. For example, The Times of India provided a detailed description of the police’s break-in:

shortly after the Congress Radio had broadcast its programme, officers and men in plain clothes rushed to the fifth floor of a building at Parekh Wadi….[They] found the door of a particular block closed, and there was no response to their knocks, the police forced open the door. The flat was in complete darkness, but after a search, the police found the youth and girl and took them in custody.

The report did not name the ‘youth’ (C. B. Jhaveri) or ‘girl’ (Usha Mehta) and it did not go into any specifics about their identities or their work for the station.Footnote 135

Yet, despite the newspapers’ vague reports, information about the broadcasters’ identities, the work of the radio station, and the raid itself seems to have spread quickly. As Thakkar notes, ‘word of mouth proved to be effective’.Footnote 136 J. N. Sahni, a journalist and politician who participated in the Bombay Quit India movement, explained in an oral interview that the Bombay police had a hard time tracking down the station. He claimed that some police officers might have even purposely let the broadcasters escape arrest and described his own personal experience when looking for the station in a building in Bombay:

And as I went, I found a place fairly empty. I thought I had been bamboozled or something. And then one of these persons came up and said: ‘Are you trying to find where the radio station is.’ I said: ‘No.’ I didn’t want to commit myself. I said: ‘No, I just want to find out this address’. He said ‘Don’t be silly. That station had been removed for the last eight days from here. We are CID men […] we don’t know where it has gone; we are also in search of it, but it is gone from here!’ So that was the attitude of the police also, not of all, but of some for them.Footnote 137

Sahni’s comments, regardless of their accuracy, suggest the raid spurred a larger conversation about the station, the broadcasters, and the admiration and loyalty they garnered.

Similarly, Usha Mehta noted in an oral interview that one of the reasons why she felt she had to write down her version of events was because she wanted to correct the many false accounts that glorified her own role and incorrectly claimed that the police had tortured her.Footnote 138 Her desire to lay rumours to rest not only demonstrates that the raid and broadcasters’ imprisonment were particularly effective at creating radio resonance and amplifying the station’s message, but also shows the importance of Mehta’s subjectivity to discussions about the station. As a young woman who had quite literally raised her voice against the empire, Mehta’s involvement in the station and her subsequent arrest spurred interest and invited conversation. The talk that surrounded Mehta’s arrest was also likely to have been related to the uniqueness and significance of her identifiably female voice on the airwaves.Footnote 139 Finally, it is also noteworthy that it is difficult to find pictures of a young Mehta or her co-broadcasters, even though contemporary accounts their arrest and of the station are plentiful. The young broadcasters’ subjectivity, like the station they founded, had a somewhat ephemeral, even secretive, character and seems to have primarily, if not entirely, circulated aurally.Footnote 140 The scarcity of images of Congress Radio broadcasters is particularly interesting when compared with the abundance of photographs of Mountbatten as supreme commander.

Congress Radio on trial

The government tried the four main organizers and Motwane, the owner of the radio shop, for violating the Indian Penal Code and the Defence of India Rules.Footnote 141 The trial started on 8 April 1943, several months after the British Government of India had crushed the Quit India movement.Footnote 142 The case was heard in a Special Criminal Court, which appears to have been set up exclusively to hear Quit India-related cases. The three male defendants denied having had any connection with Congress Radio. Mehta, in contrast, pleaded not guilty, but refused to deny her role in the radio station. Later, she came to believe that her decision helped earn the judge’s respect and resulted in a lighter sentence.Footnote 143 In her personal account, Mehta noted that the group initially considered not putting up a defence at all, but decided to defend themselves because they realized that since the station had been accused of collaborating with Axis countries, ‘the prestige of the Congress was at stake’.Footnote 144 According to Mehta, Lohia and other Congressmen helped cover the cost of the defendants’ lawyers. I have found no corroborating evidence of this, but if Mehta was correct, then this could serve as further evidence of how the trial helped garner support for the station and its broadcasters—and ultimately amplified Congress Radio’s message.Footnote 145

In a somewhat romantic manner, clearly coloured by nostalgia, Mehta described the trial as an enjoyable event: ‘All along, we used to chew chocolates or peppermints unperturbed by the efforts of the prosecutor.’Footnote 146 Mehta wrote that her comrades’ ‘clever jokes’, ‘artistic sketches’, and ‘literary flashes’ during the trial entertained all those present. Motwane’s penchant for inserting ‘Urdu shers into this speech’ amused the courtroom. While Mehta’s account might be romanticized, there can be no doubt that the court case served as an opportunity for the accused to proudly celebrate their commitment to the anticolonial movement. Mehta remarked that one of the most exciting moments in the trial was when the prosecutor noted that the court should listen to the AICC Quit India resolution, which had aired on Congress Radio. The court was unable to find the tape Congress Radio broadcasters had used and instead played the original audio-visual recording in the court. ‘Seeing Jawaharlal Nehru on the screen’, wrote Mehta, was particularly thrilling for the four defendants and their supporters in the courtroom.Footnote 147 In this way, the trial offered an opportunity to celebrate the materiality of technology and the ways in which it could serve as means of defiance against colonial rule.

Similarly, discussions about Printer’s motivations and character in the courtroom helped emphasize the defendants’ legitimacy and commitment to the anticolonial cause. The judge pointed out that Printer had knowingly deceived his colleagues about having increased the strength of the station’s transmitter. Printer, the judge noted, was an ‘unscrupulous’ individual, whose testimony could not be fully trusted.Footnote 148 Ultimately, conversations about Printer’s lack of commitment to the anticolonial movement and his questionable character helped draw attention to the defendants’ own heartfelt commitment to the cause. In this way, the Congress Radio trial echoed earlier anticolonial trials, and in particular the famed revolutionary Bhagat Singh’s trial. As scholars have shown, Bhagat’s trial and discussions about it played an important role in making him into a national hero.Footnote 149

As expected, Congress Radio’s relationship to Axis radio and Axis countries was a topic deeply debated in the courtroom. The judge concluded that the Axis government did not support the station and that at no point were pro-Axis views aired.Footnote 150 Interestingly, in reaching this conclusion the judge relied on the testimony of H. V. R. Iyenger, from the government of Bombay, whose analysis of the radio station was based on his own radio listening experience: ‘I used to also listen to Tokyo and Saigon […] and I have sufficient recollection of them to be able to broadly compare them with the Congress broadcasts. My opinion is that these do not furnish any specific evidence of fifth column inspiration.’Footnote 151 A separate investigation from the Home Office corroborated the judge’s conclusions. The report concluded: ‘the purpose behind [Congress Radio] is to foster anti-British feeling without facing the practical necessity of a choice between British Government [sic] and Japanese domination. The authors may have made use of Japanese broadcasts and may themselves be pro-Japs but there is nothing playing pro-Jap in the broadcasts.’Footnote 152

The most telling deliberation in the courtroom, however, was about the song ‘Vande Mataram’. Mehta and her comrades claimed they were playing ‘Vande Mataram’ at the exact time when the police entered the apartment. In her personal account, Mehta explained, ‘we not only refused to carry out their orders, but [refused] to get up from our seats until the “Vande Mataram” record was over’.Footnote 153 The judge disagreed with this account and argued that the police report noted that Printer had cut the fuse of the transmitter before the police entered the room so the song could not have been playing at the time of the defendants’ arrest. The three broadcasters explained that even if the transmitter was no longer working, the gramophone player continued to play the patriotic song and it would have been audible to everybody in the room. To this, the judge responded that if the gramophone player had been playing during the time of the arrest, then the needle would have been found resting on the record. The photographs, however, clearly showed that the needle was not on the record.Footnote 154 The level of detail of these discussions makes it clear that the broadcasters felt that it was not only their work with Congress Radio, but also their commitment to Indian nationalism that was on trial. Proving that the song was on the air at the time of arrest—that it had served as a soundtrack to this event—was ultimately an effort to assert their own and the station’s patriotism.

In the end, the judge found Mehta, Khakar, and C. B. Jhaveri guilty of ‘conspiracy to establish, maintain and work an unauthorized wireless transmitter’. He sentenced Khakar to five years and Mehta to four years in prison. The judge sentenced C. B. Jhaveri to just one year because the police could not provide sufficient evidence that he had played a role in the initial planning of the radio station. The judge absolved Motwane because the police could not prove that he had been aware that his employees had sold transmitter parts to Printer. The judge also exonerated V. K. Jhaveri and the justification for this absolution deserves greater attention.

The young man’s handwriting appeared on many of the gramophone records the police confiscated. His lawyer, however, argued that gramophone records were not documents because official definitions of a ‘document’ did not include aural material (see Figure 5).Footnote 155 Agreeing with the lawyer, the judge ruled that the confiscated records could not be used as evidence that V. K. Jhaveri was involved in the station.Footnote 156 It is indeed ironic that the very thing that made it possible for the station to break through the colonial government’s information gag and censorship policies—its aurality and separation from print media—ultimately saved V. K. Jhaveri from doing prison time, thanks to a lawyer’s savvy reading of colonial legal documents.

Figure 5. Image of Usha Mehta in 1998.

Conclusion

On the surface, Louis Mountbatten and Usha Mehta had little in common. Mountbatten was the supreme commander of SEAC and soon-to-be final viceroy of India, and he was also an uncle and mentor of the future queen of England’s husband. In August 1979, a member of the Irish Republican Army killed Mountbatten along with several members of his family to protest against Britain’s colonial relationship with Ireland. Usha Mehta was a student activist, who wore khadi in protest against the colonial administration’s trade policies.Footnote 157 After independence, Mehta completed a PhD and became a university professor. The Indian government recognized her anticolonial activities; in 1998, she received the Padma Vibhushan award for her activism during Quit India.Footnote 158 Despite Mountbatten and Mehta’s radically different relationship to British imperialism, their stories collided during the Second World War when they both turned to the medium of radio. Mehta took to the microphone a few months before Mountbatten began to lobby to bring the Marconi transmitter to Ceylon. Interestingly, these two individuals, from such different walks of life, intuitively understood that radio’s materiality could convey a powerful message, at times more influential than the broadcast content.

But, if Mountbatten’s Radio SEAC and Mehta’s Congress Radio had similar political ambitions, their project outcomes differed. Radio SEAC’s transmitter did not reach Ceylon until after the war’s end and the station was far from invoking the colonial sublime in the ways Mountbatten and others in British government had hoped. Part of the reason for Radio SEAC’s absence from historical accounts is because it was essentially a failed scheme. Mehta’s local and makeshift underground station shut down only months after it went on air and by some accounts it too could be considered an unsuccessful enterprise. However, a careful reading of the events reveals that the dramatic police raid and the prolonged court case against its organizers ultimately amplified Congress Radio’s message. While Congress Radio remained a local Bombay project, it succeeded in evoking the anticolonial sublime. Yet, as Thomas Mullaney reminds us, we should not focus too much on trying to determine these stations’ successes or failures because technologies need not derive their relevance from the magnitude of their ‘immediate effect’, but from ‘the intensity and endurance’ of the engagement they create.Footnote 159

The stories of Radio SEAC and Congress Radio, while seemingly unconnected, read alongside one another illustrate how during the Second World War the medium of radio could simultaneously serve and contest the colonial state. They demonstrate how the global war set the stage for the enduring rivalry between state-sponsored radio networks and competing stations in the decades following independence in South Asia.

Competing interests

None.