Introduction

On 30 September 1956, the president of the Republic of Indonesia Achmed Sukarno (1901–1970) paid his first visit to the People’s Republic of China (hereafter PRC).Footnote 1 Upon his arrival at Xijiao Airport in Beijing, he received a rousing welcome from the PRC’s senior leaders who were waiting for him at the airport, including Chairman Mao Zedong (1893–1976), Prime Minister Zhou Enlai (1898–1976), and the two vice chairmen Liu Shaoqi (1898–1969) and Song Qingling (1893–1981), as well as many other influential figures such as the Chinese ambassador to Indonesia Huang Zhen (1909–1989), the Chinese-born Southeast Asian entrepreneur Chen Jiageng (also known as Tan Kah Kee, 1874–1961), and the China-Indonesia Friendship Association’s director Burhan Shahidi (1894–1989). About 300,000 people lined the two sides of the more than 20-kilometre long road from the airport to the Zhongnanhai, holding up portraits of Sukarno, waving Indonesian flags, and cheering ‘Long Live Bung Karno’ and ‘Long Live Peace’.Footnote 2 The colourful posters on the buildings and walls, which read ‘Long Live China-Indonesia Solid and Unbreakable Friendship’ and ‘Long Live the Peace of Asia-Africa and the World’, echoed Sukarno’s advocacy of the peace and unity of Asian and African people during his opening address at the Bandung Conference a year previously.Footnote 3 The PRC’s People’s Daily published triumphant reports and photos of Sukarno’s visit (see Figure 1), marking this event as a milestone of the newly established PRC’s diplomatic achievements.Footnote 4 In the evening, Mao hosted a state banquet for Sukarno, where the two leaders delivered speeches that stressed the two nations’ shared memory of anticolonial revolutions and expressed the hope that the China-Indonesia fraternal relationship would be strengthened.Footnote 5 In addition to military officers, politicians, and journalists, the Presidential Palace painter Dullah (1919–1996) and the Balinese art delegates, whom Sukarno had invited to accompany him to China, also attended the banquet and received a warm welcome. The next day, when more than 500,000 citizens in Beijing celebrated the PRC’s seventh anniversary, Mao invited Sukarno to watch the military parade in Tiananmen Square. The group photo entitled ‘Asian solidarity’ (see Figure 2), showing Sukarno, Mao, and Nepal’s Premier Tanka Prasad Acharya (1912–1992) standing together and reviewing the parade, was disseminated worldwide through the PRC-backed English-language magazine China Reconstructs designed for foreign readers. It served as a visual statement of China’s ties with Indonesia and its vision for the unity of Asia.Footnote 6

Figure 1. Mao welcomed Sukarno in Beijing on 30 September 1956.

Figure 2. Mao invited Sukarno to watch the military parade on 1 October 1956.

It was in such an amicable atmosphere that Prime Minister Zhou gifted Sukarno a two-volume, oversized, quadrilingual (Indonesian, Chinese, English, and Russian) anthology entitled Paintings from the Collection of Dr. Sukarno President of the Republic of Indonesia (see Figure 3). With 206 fine-grained images printed from photographs of the original paintings selected by Dullah from Sukarno’s collection, the anthology included paintings of various subjects and in different styles, none of which had previously been published in any country, including Indonesia.Footnote 7 As an keen amateur artist and patron who had kept creating and collecting artworks even during the turbulent period of the anticolonial revolution,Footnote 8 Sukarno received this gift with excitement as it fulfilled his long-held desire to have his private art collection published and become known worldwide; as he said, ‘thanks to this anthology of paintings, the world comes to know Indonesia’.Footnote 9 A handwritten letter by Sukarno (see Figure 4) emphasized the anthology’s diplomatic significance in strengthening the brotherly ties between the Chinese and Indonesian people.Footnote 10 In the same spirit, the anthology’s foreword, written by the People’s Fine Arts Publishing House publisher in Beijing, described this anthology as a symbol of the growing friendship and cultural exchanges between the two nations.Footnote 11

Figure 3. Cover of Paintings from the Collection of Dr. Sukarno President of the Republic of Indonesia, vol. 1 (Peking: People’s Fine Arts Publisher, 1956).

Figure 4. A handwritten letter by Sukarno.

The promotion of Sukarno’s art collection in China generated widespread enthusiasm for Indonesian history and culture and profound sympathy for the Indonesian anticolonial revolution. In return, the Chinese ink paintings carefully selected by Mao and Zhou as national gifts for Sukarno reinforced his admiration for China’s classical aesthetics and the country’s recent achievements in modern industry. The ongoing art exchange activities, as this article argues, inspired the two nations to put aside their political and ideological differences and turn to embrace their shared Asian history and culture. They carried on the spiritual heritage of the Bandung Conference and anticipated the development of Sukarno’s idea of ‘Guided Democracy’. Moreover, implementing art diplomacy coincided with and facilitated China’s trade with Indonesia, which can be considered part of China’s response to the commercial embargo imposed by the United States in the aftermath of the Korean War (1950–1953).

Although China-Indonesia cultural exchanges through visual art received significant media coverage at the time, it has largely escaped the scrutiny of historians. Scholars of cultural history have paid increasing attention to China-Indonesia interactions in the spheres of literature, music, dance, theatre, and film,Footnote 12 but visual art has been under-recognized. Relevant questions concerning the context and impact of art relations between China and Indonesia in the mid-twentieth century have remained unexplored. Why was Sukarno’s private collection of paintings published in China, a nation that the Indonesian government regarded as a threatening power in the late 1940s and early 1950s? Why did publication take place in the year 1956? How was the benign subject of art instrumentalized to wage and advance China’s diplomatic ties with Indonesia as a non-communist nation during the Cold War? And, to what extent could China’s traditionalist paintings help construct its modern profile as an independent, peace-loving, and industrialized nation? These questions cannot be answered without considering China’s and Indonesia’s geopolitical positions in the early Cold War, especially their respective relationships with the two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union. By contextualizing the making of the anthology Paintings from the Collection of Dr. Sukarno President of the Republic of Indonesia in the changing climate of international politics between the late 1940s and 1950s, the first section of this article analyses the geopolitical forces and national interests instrumental in shaping China’s art diplomacy and its cultural connection with Indonesia.

Existing literature on the Chinese art history of the Maoist era (1949–1976) either situates visual art within the national framework by stressing the value of propagandistic art forms such as new year pictures, woodcuts, and posters, or concentrates on the artistic affinity between China and Soviet Russia with an emphasis on China’s institutionalization of socialist realist paintings.Footnote 13 Recent studies on China-Romania art exchanges reinforce the constructed model that confined the scope of Chinese art within the Socialist bloc.Footnote 14 Less well documented is the fact that in the 1950s China actively sought dialogues with non-socialist countries in East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, Africa, and Europe through the channel of visual art.Footnote 15 In broadening the scope of Chinese art history to a transnational and cross-ideological context, this article’s first and second sections investigate the China-Indonesia art networks composed of political leaders, diplomats, cultural delegates, and individual artists who collectively contributed to reproducing Sukarno’s collection of paintings in China. They serve as an entry point to reconsider art’s political goals and agency in the milieu of China’s changing relations with the world during the early Cold War period.

Artworks are often under-recognized and dismissed as insignificant or trivial vis-à-vis the military and technological races at the core of the Cold War. Scholars have long discussed the indispensable value of literature in shaping the ideological rivalry between the two superpowers.Footnote 16 The significance of literature in cultural warfare is explicitly expressed in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s well-known claim: ‘books are weapons’, and literary studies have researched the function of literature in China’s diplomatic ties with Africa, Europe, and South Asia.Footnote 17 However, visual art played a no less significant role in the cultural battlefield. The binary opposition between American abstract expressionism and Soviet socialist realism suffices to exemplify the impact of visual art in communicating the different political ideologies of the two superpowers.Footnote 18 The third section of this article, through a visual analysis of three Chinese ink paintings selected as national gifts for Sukarno, argues for the irreplaceable role of artistic elements in the China-Indonesia fraternal relationship, and it complicates the generally accepted bipolar art landscape of the Cold War defined by the two mainstream art of abstract expressionism and socialist realism. It is true that the Chinese Communist Party (hereafter CCP) and a wide array of Indonesian nationalist forces respectively relied on the Soviet Union’s and the United States’ economic aid during the revolutionary period, and their subsequent art and culture inevitably bore the influence of socialism (in China) and capitalism (in Indonesia). Nevertheless, China-Indonesia interactions in the field of art entail and amplify the tradition of each country’s indigenous art forms, presenting an Asian mode of art history beyond the Western-centric art narrative of the Cold War.

Transcending ideological divisions: A prelude to China-Indonesia art exchanges

Although the Republic of Indonesia (est. 1945) and the PRC (est. 1949) enacted a formal diplomatic relationship in April 1950, the two nations were often hostile, if not completely antagonistic. When the CCP defeated the Nationalist Party (also known as the Kuomintang, hereafter KMT) in the Civil War (1945–1949), it built up the United Front Work Department to disseminate ideas of Marxism-Leninism and Maoism among the communists and ethnic Chinese in India, Indonesia, Vietnam, and other countries in Asia.Footnote 19 Furthermore, Mao’s announcement in June 1949 of the foreign policy ‘Leaning to One Side’ and China’s entry in December 1950 into the Korean War (1950–1953) aligned China with the Soviet Union.Footnote 20 The nationalist-led Indonesian government perceived the CCP’s expansive influence in Southeast Asia as a threat and categorized the CCP as a follower of the Soviet Union’s communist authoritarianism.Footnote 21 Meanwhile, the CCP criticized the Indonesian government for its rapport with the United States and Japan. From Mao’s perspective, Sukarno’s acceptance of the American intervention in the Renville Agreements (1948) and his compromise with the Dutch colonialists during the Dutch-Indonesian Round Table Conference (1949) made the Indonesian government subservient to Western imperialists and colonialists. The Chinese government was particularly irritated by the Indonesian government’s acquiescence to the political activities of the KMT’s branch in Jakarta.Footnote 22

The two nations’ different aesthetic preferences mirrored and magnified their political tensions, blocking the channels of art exchanges. In the early 1950s, the Dutch painter Ries Mulder (1909–1973) was invited to teach modern Western painting at the Bandung Technical Institute, while the Soviet painter Konstantin M. Maksimov (1913–1994) taught socialist realist painting at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (hereafter CAFA) in Beijing.Footnote 23 While prestigious Indonesian painters such as Affandi (1907–1990), Sindu Sudjojono (1913–1986), and Hendra Gunawan (1918–1983) experimented with European expressionist paintings and the younger generation of Indonesian painters publicly displayed their Cubist and abstract paintings, Chinese official art journals published articles condemning such modern European art styles as the ugly aesthetics of the bourgeois class, and it was not until the 1980s that abstract paintings became legitimate in the Chinese art world.Footnote 24 Under these circumstances, art exchanges between the two nations were almost stagnant.

China-Indonesia relations began to thaw when the left-wing nationalist Ali Sastroamidjojo (1903–1975) assumed the position of Indonesia’s prime minister in 1953. In August of the same year, Ali appointed Arnold Mononutu (1896–1983) as the first Indonesian ambassador to China; he had previously cautioned against aligning the CCP with Soviet communism and argued for the CCP’s independence in its fights for the national interest.Footnote 25 Between 1953 and 1955, the People’s Daily constantly reported the increasing votes gained by the Communist Party of Indonesia (Partai Komunis Indonesia, hereafter PKI) in the national elections of Indonesia.Footnote 26 In the meantime, the Indonesian government was pressured by the United States’ various actions to draw it into alignment with the West.Footnote 27 The Ali-led cabinet’s claim for West Irian, its advocation of independent foreign policies, its decision not to join the Washington-backed Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (hereafter SEATO), and its proposal for the Bandung Conference suggested Indonesia’s changing attitude towards the United States.Footnote 28 Actions such as replacing the Indonesian charge d’affaires in Beijing with an official Indonesian embassy and expanding the PKI-based Institute of the Culture of the People (Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat, hereafter LEKRA) networks with Chinese writers and artists provided institutional support for the cultural exchanges between the two nations in the ensuing years.Footnote 29

In parallel, China’s inclination towards independent diplomacy was enhanced by the subtle change in the Beijing-Moscow relationship resulting from Joseph Stalin’s (1878–1953) death.Footnote 30 Slow diplomatic development was another factor that motivated China to extend its geopolitical orbit to include countries beyond the Socialist bloc. Within the first year of the PRC’s establishment, China had developed diplomatic relationships with 19 countries, but this number increased by only five from 1951 to 1955.Footnote 31 The Geneva Conference held between 26 April and 20 July in 1954, however, provided timely opportunities for China to develop new allies with non-socialist countries. One month after the Geneva Conference, Mao restated the concept of the Intermediate Zone, proposing China’s peaceful coexistence with Asian and European countries regardless of their different political ideologies.Footnote 32 In late 1954, China introduced a new diplomatic policy called the ‘Peaceful United Front’, seeking to unite with countries despite their different political ideologies. The ideology-based diplomacy ‘Leaning to One Side’ formulated in the late 1940s now gave way to a more pragmatic diplomacy that transcended the dichotomy of communism and capitalism.Footnote 33

At this crucial juncture of renewing diplomacy, art came to play a role in reducing the tensions between China and Indonesia that had accumulated in the previous years. Just one month after the Geneva Conference, China welcomed the Indonesian Art Delegation in Beijing. Zhou Yang (1908–1989), then the vice director of the Propaganda Department, acclaimed the delegation’s contribution to the China-Indonesia bond and Asian peace.Footnote 34 Additionally, the Ministry of Culture organized the Indonesian Art Exhibition at the Waterside Pavilion of Zhongshan Park in Beijing, displaying 96 paintings selected by the Indonesian political officer and painter Henk Ngantung (1927–1991), who was a member of the China-Indonesia Friendship Association and was appointed by Sukarno as the first deputy governor of Jakarta between 1960 and 1964. Ngantung chose paintings with subject matter that would evoke the shared history and culture of Asian countries. Unlike the art exhibitions in Bandung that showed Cubist and abstract paintings, the art exhibition in Beijing displayed Indonesian paintings with subjects ranging from landscapes, peasants, workers, and wars of independence (see Figure 5). Chinese artists and art critics praised these paintings for expressing Asian people’s common pursuit of independence and peace.Footnote 35 Accompanied by Ngantung, Prime Minister Zhou and Ambassador Mononutu attended the opening ceremony. Portraits of Sukarno and Mao hanging in the exhibition hall indicated the diplomatic purpose of this art event.Footnote 36 The 10-day exhibition caused quite a stir, attracting more than 30,000 visitors.

Figure 5. Indonesian oil paintings Offerings to the Rice Goddess and Refugees published in China.

The Chinese people’s enthusiasm for Indonesian culture was also augmented by Balinese dance performances in seven cities: Beijing, Tianjin, Shenyang, Nanjing, Shanghai, Hangzhou, and Guangzhou. In return, China dispatched dance troops to Indonesia between 1954 and 1955. As the historian Emily Wilcox observed, dance diplomacy was initiated at approximately the same time as the Colombo and Bogor conferences, at which the five sponsoring countries of the forthcoming Bandung Conference, namely India, Indonesia, Burma, Ceylon, and Pakistan, discussed the decision to invite China to the 1955 gathering of newly independent nations.Footnote 37 Moreover, the practice of dance diplomacy also coincided with the Chinese trade delegation’s visit to Indonesia between June and August 1954, when the two nations signed a trade agreement and payment protocol, establishing bilateral import and export relations. Considering that the China Committee (CHINCOM), a consultative group of Western allies established in Paris in 1950 to govern trade with communist nations, had instituted increasingly strict policies and embargoes on China, entering into commercial and cultural contact with Indonesia can be considered as China’s response to these restraints.

In November 1954, Prime Minister Zhou appointed Huang Zhen as China’s second ambassador to Indonesia; he would soon play a pivotal role in the publication of Sukarno’s art collection.Footnote 38 Huang’s triple identity as a general, a diplomat, and a painter made him the ideal candidate for this position. As a senior member of the CCP and a Long March (1934–1935) veteran, Huang firmly believed in communism and the CCP’s leadership in China. Before taking the new position as ambassador to Indonesia, he had accumulated diplomatic experience as China’s first ambassador to Hungary between 1950 and 1954.Footnote 39 Significantly, like Sukarno, he was an amateur artist who had received formal education in traditional Chinese painting and Western sketching at the Shanghai Fine Arts College (est. 1912) between 1925 and 1927. The sketches he created during the Long March were considered valuable visual records of the march, depicting mountains and rivers the Red Army travelled through (see Figure 6) and peasants from diverse minorities whom the Army met, such as the Miao in Guizhou province, the Hui in Gansu province, and the Yi and Zang in Yunnan and Sichuan provinces. These sketches were compiled into an anthology and published in six editions between the 1930s and the 2000s.Footnote 40 Whether Huang gave his anthology to Sukarno is unknown, but he presented it to the renowned French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) in 1966, when he served as ambassador to France. Zhou was well aware of Huang’s artistic talents and his effective leadership in the cultural milieu. Before Huang’s departure to Indonesia in November 1954, Zhou met Huang in Guangzhou to instruct him on the complex political situations in Indonesia and suggested that, in addition to developing political ties with Indonesia, he should pay close attention to the China-Indonesia cultural connection. Finally, Zhou expressed his confidence that Huang would become Sukarno’s good friend.Footnote 41

Figure 6. Huang Zhen, Trekking through Jianjin Mountain, 1934–1935, ink on paper.

Heeding Zhou’s advice, Huang endeavoured to develop China-Indonesia art exchanges. Just one month after presenting his credentials to Sukarno, Huang organized the Chinese Arts and Crafts Exhibition in Jakarta with the help of the cultural counsellor Sima Wensen (1916–1968), a left-wing writer whom Sukarno and Dullah invited to view Sukarno’s collection of paintings and talk about the publication of Sukarno’s anthology. High-ranking officers, including Sukarno, Mohammad Hatta (1902–1980), and Ali, attended the opening ceremony. The exhibition attracted about 80,000 visitors in Jakarta alone and then travelled to Sukarno’s hometown in Surabaya, where about 130,000 people visited the show.Footnote 42 In the same year, the Indonesia-China Friendship Association was established in Jakarta and Beijing. These cultural events built a solid foundation for China’s presence at the Bandung Conference scheduled for three months’ time. During the conference, Zhou Enlai’s declaration of the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence and his signing of the China-Indonesia Dual Nationality Treaty with Sukarno solidified China’s profile as a reasonable and peace-loving nation.Footnote 43 Moreover, China also showed its desire for cultural exchanges with the Third World. At the conference’s public session, Zhou called for mutual respect for different cultures, and in the session for the delegates of the participating countries, Huang advocated for art and cultural communications to consolidate the Asia-Africa bond.

Four months after the conference, a 77-member Chinese cultural delegation visited Indonesia. Accompanied by Huang Zhen, Sukarno welcomed the delegation’s non-communist director Zheng Zhenduo (1898–1958) and the vice-director Zhou Erfu (1914–2004) at his Palace of Independence. Under the guidance of Dai Ailian (1916–2006), then the principal of the Beijing Dance Ensemble, Chinese dancers performed Peking Opera and traditional dances in Jakarta, Bandung, Yogyakarta, Surabaya, Bali, Medan, and other cities, attracting about 400,000 visitors.Footnote 44 The Islamic Xinjiang dancer Zohara Shahmayeva’s (b. 1934) folk dances became very popular among Indonesian audiences, to the point that she signed more than 200 commemorative albums a day. Heeding Zhou’s instructions of ‘not just introducing our culture; you must also study their culture’, the Chinese dancers studied with local Balinese dancers during their stay in Indonesia. It was noticeable that not all dancers felt comfortable with Indonesian dances. While Dai Ailian published an article entitled ‘I Love Balinese Dances’ to help people understand and appreciate different types of Balinese dances, her students had initially hoped to learn Western ballet because they had considered ballet a high art before the establishment of the PRC.Footnote 45 The dancers’ individual aesthetic preference for Western art, which they had cultivated in the Republican period (1912–1949), was not in accord with China’s new foreign policies. It was only through long-term learning and training that they came to appreciate the artistic features of Balinese dances.Footnote 46

Song Qingling’s visit to Indonesia, scheduled one month before Sukarno arrived in Beijing, set a positive tone for re-evaluating Balinese art’s cultural significance in the newly independent nation of Indonesia and its potential for cultural exchanges. In Bali, Song was impressed by indigenous paintings and crafts, and in her report on the visit, she expressed her admiration for Balinese traditional art:

I admire the artistic talent and hard work of the Balinese people. They have preserved traditional Balinese art. However, as a result of colonial rule, these artworks were not valued in the past, and the lives of these art workers were difficult. I believe that in the future, with the help of the local government, these arts and crafts with traditional ethnic styles will play an important role in exchanging cultures and boosting the economy.Footnote 47

Shao Yu (1919–1992), deputy director of the People’s Fine Arts Publishing House responsible for printing Sukarno’s anthology, wrote articles introducing the diverse subjects and forms of Balinese painting to Chinese readers. From his perspective, some mythologies depicted in Balinese painting were quite similar to those in China because the paintings embodied ‘oriental characteristics’ that convey the spiritual pursuit of benevolence and justice.Footnote 48 The constant art exchange activities, in which individual artists, politicians, and institutions engaged before and after the Bandung Conference, enhanced mutual understanding and respect between China and Indonesia. They anticipated the China-Indonesia honeymoon in 1956, when Sukarno visited China, met with Mao, and received the gift Paintings from the Collection of Dr. Sukarno President of the Republic of Indonesia.

Orchestrating the reproduction of Sukarno’s art collection: The peak of China-Indonesia art exchanges

Huang Zhen’s personal relationship with Sukarno was a crucial factor in driving China-Indonesia art exchanges to a new high. Huang’s artistic background facilitated deep conversations with Sukarno outside their formal meetings. Sukarno was very fond of Chinese traditional ink paintings and viewed Huang as ‘a romantic landscape painter’ who could ‘create eye-catching calligraphy and painting’.Footnote 49 Sukarno invited Huang to see his private art collection, even showing Huang some of his nude paintings which he rarely revealed to others because they were considered morally unacceptable in Indonesian society at the time. Huang’s professional comments on the paintings’ lines, strokes, colours, and compositions further earned Sukarno’s appreciation and trust. From Sukarno’s point of view, Huang’s ‘artistic eyes’ distinguished him from the conservatives who viewed pure art with moral prejudice.Footnote 50 Their frank discussions about paintings strengthened their interpersonal ties. In one informal conversation, Sukarno mentioned to Huang that he had been thinking of publishing his art collection and suggested that China might be able to help him fulfil this goal.Footnote 51 Huang soon conveyed Sukarno’s request to Prime Minister Zhou, who promptly undertook the endeavour. With Zhou’s support, a team of experts selected from Beijing and Shanghai, including photographers, translators, editors, graphic designers, printers, and bookbinders, was engaged in making the anthology for Sukarno’s collection. Together with Shao Yu, the photographer Yang Rongmin (b. 1928) and the director of the Beijing Xinhua Printing House Jiang Xinzhi (b. 1943) were dispatched to Jakarta to photograph 206 oil paintings selected from Sukarno’s collection by Dullah. More than 200 bookbinders gathered at the People’s Fine Arts Publishing House in Shanghai and worked day and night for months, completing a total of 400 two-volume anthologies composed of tipped-in plates. Ten of them were made with hot stamping and sheepskin book covers, especially designed for Sukarno. To ensure that the anthologies were transported to Beijing before Sukarno’s visit, the Shanghai Railway Bureau assigned an exclusive Shanghai-Beijing express train to transport the anthologies to Beijing, and they arrived just two days before Sukarno.Footnote 52 Some of them were sold for 150 RMB per volume at the Xinhua bookstores in big cities in China, and many others were gifted by Sukarno to his international friends.

Sukarno said that the anthology would teach the world about Indonesia, and it is indeed a visual encyclopedia of Indonesian archipelago landscapes, religious rituals, cultural festivals, local people’s daily lives, and the wars for independence. Each volume unfolds with a portrait of Sukarno created by Basuki Abdullah (1915–1993), in which Sukarno stands upright and faces the viewers directly with a look of determination and composure (see Figure 7). The Songkok hat that Sukarno wears in the portraits suggests the value he placed on indigenous customs. In conjunction with the anthology, Sukarno’s biography and speeches were published in Chinese to disseminate his political ideas and experiences of leading an anticolonial revolution.Footnote 53 Chinese readers learned from the print media about Sukarno’s lifelong respect for Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924) and Sun Yat-sen (1866–1925), the two revolutionary leaders whose ideas were inspiring sources for his philosophy of Pancasila or Five Principles (nationalism, internationalism, democracy, social prosperity, and belief in God). The wide circulation of Sukarno’s portraits and his speeches built up his heroic image as the father of independent Indonesia, eliciting strong sympathy and admiration for his spirit of anti-imperialism and anticolonialism.

Figure 7. Basuki Abdullah, Dr. Sukarno President of Republic Indonesia.

Following Sukarno’s portrait, the book presented figure paintings of dancers, vendors, soldiers, arrack drinkers, farmers, cock-fighting performers, pilgrims, weaving maids, mothers, and children, alongside genre paintings of festivals and markets, collectively presenting a vivacious picture of Indonesia (see Figure 8). While paintings of religious mythologies and cremation ceremonies aroused viewers’ interest in the time-honoured history of indigenous ritual culture, landscape paintings exposed readers to the broad space of archipelagos, ranging from the Ratu Harbour of West Java to the Merapi Volcano of Middle Java, the Sarangan Lake of East Java, the mountainous area of Bandung, the Minangkabau Cliff of Sumatra, and the seas of Bali and Sulawesi.

Figure 8. Widja, The People of Bali Welcome President Sukarno.

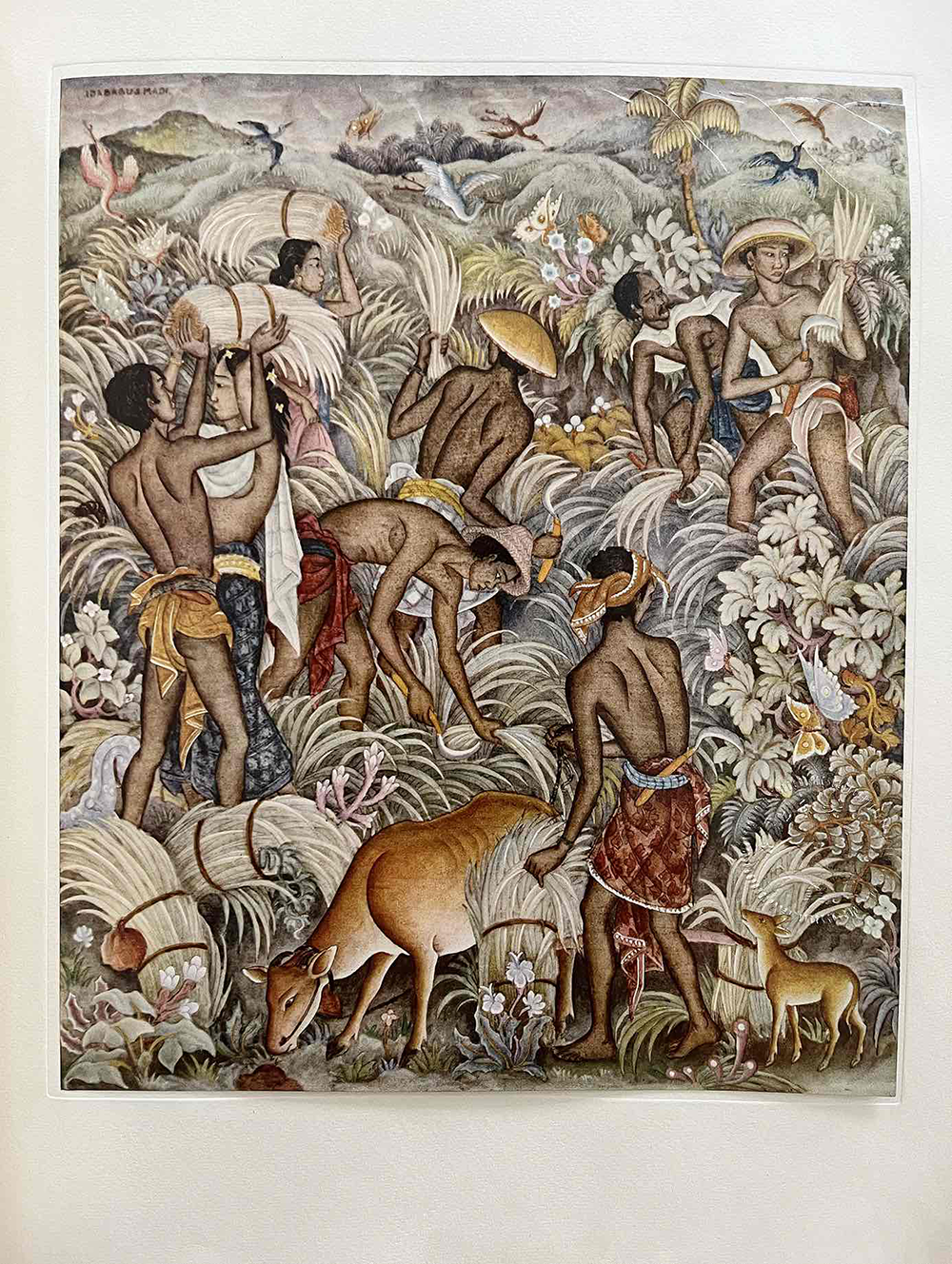

The anthology also contains paintings that subtly depict local people’s harsh life under Dutch colonial rule. The paintings, which vividly depict male and female peasants working in large fields of yellow wheat (see Figure 9), might at first glance be interpreted as an expression of peaceful and pastoral life or as a form of homage to the glory of labour. However, viewers familiar with Sukarno’s public complaints about the meagre salaries and unfair treatment that Indonesian farmers received from Dutch colonialists would have noticed traces of exploitation in the paintings: the farmers’ thin and emaciated bodies suggest they suffer from long-term malnutrition; the gestures of bending, carrying, and transporting reveal the toll of heavy physical labour; the blank gaze, closed lips, and stolid faces convey their silent endurance and lack of enthusiasm for life. The farmers depicted in these paintings were those whom Sukarno described at the Bandung Conference as the ‘voiceless’ and ‘unregarded’ people living in ‘poverty and humiliation’ and ‘for whom decisions were made by others’.Footnote 54

Figure 9. I. B. Made, Cutting Grass.

Dullah consciously decided to include a handful of history paintings in the anthology to represent the Indonesian people’s fights for independence. According to him, Sukarno was the first patron of Indonesian history paintings. From Sukarno’s perspective, history paintings not only had documentary value for the newly independent nation but could also be used to illustrate textbooks for school education.Footnote 55 Dullah’s Preparing for Guerilla Warfare, Affandi’s The Militia Plan Their Battle Tactics, and Sudjojono’s series of paintings of military commanders, soldiers, and young guerrillas vividly depict the Indonesian people’s courageous resistance to the colonial invasion. The romantic style of Basuki Abdullah’s paintings is manifested in the work Diponegoro Commanding a Battle which features intensive strokes, colour contrasts of red, black, and white, and a composition similar to the French painter Jacques-Louis David’s (1748–1825) famous painting Naopleon Crossing the Alps (1801). It visually constructs the Javanese prince Diponegoro (1785–1855), who dedicated himself to fighting against the Dutch control of Java, as a national hero, comparable to the French military commander and political leader Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821). Sudjojono’s Revolutionary Comrades-in-Arms (see Figure 10) represents a group of 19 soldiers composed of children, teenagers, veterans, intellectuals, and artists who, despite their different facial expressions of indignation, sadness, contemplation, and calm, upheld the same belief inscribed at the top of the painting, which reads ‘The call of the era brings us to one room, to one place, under the one sky, in the one revolution. This is the Indonesian Revolution.’Footnote 56 Sukarno attached great importance to this painting and had a photo taken with it. The photo shows a serious-looking Sukarno clenching his fists, as if he was calling on people to inherit the fighting spirit of these 19 soldiers, some of whom had lost their lives during the anticolonial revolution.

Figure 10. Sindu Sudjojono, Revolutionary Comrades-in-Arms.

Paintings from Sukarno’s collection played a significant role in Indonesia’s patriotic education and modern art history. During the late 1940s and 1950s, when art museums were not established in Indonesia, artists and the general public learned about Indonesian art through Sukarno’s collection, which was saved in the Istana Merdeka (Palace of Independence), the Istana Negara (State Palace), and the palaces in Bogor and Tjipanas. These paintings provided the younger generation of artists with a diversity of subjects, styles, and techniques. Furthermore, painters such as Dullah, Basuki Abdullah, Sudjojono, Agus Djaya (1913–1994), and Henk Ngantung, who had a close relationship with Sukarno, developed Indonesian realist art during the wars for independence by integrating their artistic practice with a national consciousness of Indonesian identity and a political goal of anticolonialism. Some of them became leading figures of the LEKRA or faculty members of the Academy of Visual Art (Akademi Seni Rupa Indonesia, ASRI) founded in Yogyakarta in 1950. Despite various art styles, these painters engaged art in the wars for independence. Their socially engaged art differed from Bandung art which prioritized pure form over political subjects. They defined Indonesian realist art in relation to the political movements of nationalism and anticolonialism.Footnote 57

The promotion of Sukarno’s art collection in China constructed a perception of Indonesia as a mirror of China itself, from its vast and varied territory, to its time-honoured native Asian culture, to its modern history of the anticolonial revolution. In addition to coverage in art journals and pictorial magazines, the People’s Daily introduced the anthology twice before it was published and proclaimed it as a significant marker of China-Indonesia cultural exchanges.Footnote 58 In particular, the wide circulation of the reproductions of paintings that featured the subject of anticolonial wars aroused great sympathy among the Chinese people, who recognized a revolutionary experience similar to their own. In reviewing Sudjojono’s Revolutionary Comrades-in-Arms, Shao Yu referred to the photo that showed Sukarno standing in front of the painting, and implied that the Indonesian and Chinese people shared feelings about colonialists:

Dr. Sukarno, President of the Republic of Indonesia, leaned close to this painting and took a photo. When we saw this photo, we were deeply moved by the serious expression that he showed when taking the photo with his former revolutionary comrades. Today, when the colonialists are still able to run amok in Asia, Africa, and some other parts of the world, the feelings of the Indonesian people and their leaders are particularly easy to be understood by the Chinese people.Footnote 59

In Shao’s view, the paintings representing the Indonesian struggles for independence were an ode to patriotism and peace. Shao himself created artworks to convey to Chinese readers the Indonesian people’s love of peace. In his portrait of an Indonesian child, Shao inscribed, ‘I created a portrait of this child on the Jakarta street; I painted her smart and wise eyes; [I] painted her wish for peace and happiness’.Footnote 60 His watercolour Jakarta Street (see Figure 11), which depicts motorized vehicles and tall buildings, presents Jakarta to Chinese viewers as a peaceful, modernist, and industrialized city. Shao’s emphasis on the theme of peace was reminiscent of what Sukarno advocated in his opening address at the Bandung Conference, when he claimed, ‘we Asian and African people must be united’ and ‘united by a common determination to preserve and stabilize peace in the world’.Footnote 61 It also corresponded to the Chinese campaign for peace in the first half of the 1950s, when the masses were called on to sign the government’s statement of peace, and elementary and high school students drew doves of peace. Around the same period, the Chinese government published The China-Indonesia Friendly Relationship and Cultural Exchange, a book tracing cultural contact between China and Indonesia back to the year 398 ce, when a Chinese monk first arrived in Java.Footnote 62 These visual and textual materials purposefully avoided the political discrepancies that had caused the tension between the two nations in the past decade and instead reflected the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence.

Figure 11. Shao Yu, Jakarta Street, watercolour.

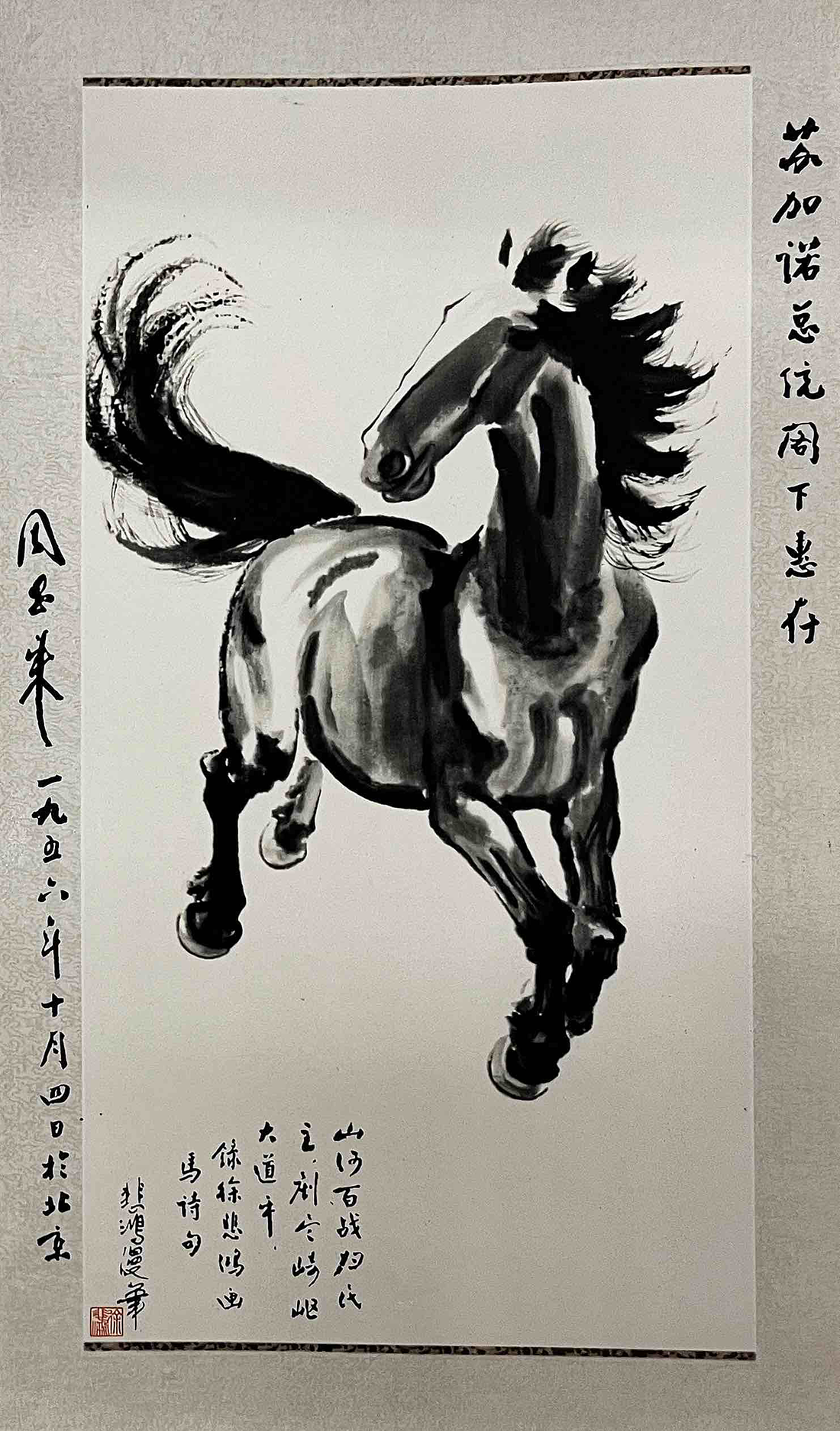

The atmosphere of camaraderie created through the art exchanges also enriched the interpersonal communications between Sukarno and Mao, who had a common interest in art. In the revolutionary period, Sukarno created landscape paintings and Mao wrote poems, both expressing a deep affection for the lands of their respective countries. Artistic creation had been a valuable source of their passion for their anticolonial revolutions. During Sukarno’s visit, the two leaders’ mutual trust was reinforced not only in their official meetings, where Sukarno expressed his hope that China would join the United Nations, but was also consolidated when they attended the Peking Opera Yandangshan, the Balinese Art Delegation’s dance performance, and the China-Indonesia Pictures Exhibition.Footnote 63 Discovering Sukarno’s interest in Chinese traditional paintings, Mao and Zhou gave him several ink paintings created by prestigious painters, including Qi Baishi’s (1864–1957) Pine and Peony and Plum Blossom, Xu Beihong’s (1895–1953) Horse, Zhang Xuefu’s (1911–1987) Transform Floods into Hydraulic Engineering, bird-and-flower paintings by Ren Bonian (1840–1896) and Yu Fei’an (1889–1959), and landscape paintings by Chen Shaomei (1909–1954).

The advancement of Indonesia’s relationship with China signified its independent diplomacy that Sukarno had struggled for under pressure from SEATO. Anak Agung (1921–1999), then Indonesia’s foreign affairs minister, claimed that Sukarno’s visit to the PRC in 1956 was a ‘real milestone in Indonesia’s political development both in the domestic field and in the conduct of its foreign policy’.Footnote 64 Sukarno’s visit to industrial and cultural sites in China anticipated his establishment of ‘Guided Democracy’.Footnote 65 Specifically, Sukarno’s visit to Sun Yat-sen’s mausoleum in Nanjing refreshed his memory of leading the wars for independence and conceiving his political philosophy of ‘Pancasila’ (Five Principles). Sukarno called Sun’s third wife Song Qingling (also known as Madame Sun Yat-sen) ‘sister’ and expressed his gratitude for her gifts, which included a bronze statue of Sun, a photograph of Sun and Song’s wedding, and two doves of peace. Moreover, his visits to an automobile factory in Changchun, a steel plant in Anshan, and a dockyard and textile mill in Shanghai reinforced his aspiration to modernize and industrialize his own country. In a speech delivered at the Anshan Workers Meeting, Sukarno expressed his excitement at hearing the loud sounds from factories, machines, haulage motors, and forging irons.Footnote 66 In his farewell speech before returning to Indonesia, Sukarno expressed how deeply impressed he was by the Chinese people’s enthusiasm for socialist construction, saying, ‘Wherever we are, we witnessed how hard Chinese people were working, building, and constructing. Let me repeat, they are constructing, constructing a new Chinese society.’Footnote 67

Sukarno’s observation of Chinese socialist construction was well-grounded in reality. By the mid-1950s, the end of the Korean War, the completion of land collectivization, and the nationalization of the ownership of the commercial sector collectively set China on a new road to industrial construction and technological improvement. When Sukarno visited China in 1956, the country was at the peak of industrial construction under the auspices of the First Five-Year Plan. People working in different fields gained self-confidence and national pride. To the government, the achievements in domestic society demanded a new international profile that would distinguish China from its feudal and semi-colonial past. Art diplomacy served this end. Sukarno’s perception of China as an independent, peaceful, and industrialized power was solidified not only by his meetings with politicians and his visits to factories in China, it was also reinforced by the visual representation in the ink paintings that he received from Mao and Zhou.

Paintings as national gifts: Drawing China’s new profile as a peaceful and industrial power

Chinese paintings gifted to Sukarno were created with ink medium and in scroll format, yet they were prominent examples illustrating how traditionalist paintings were applied to build up a modern image of China defined by political peace and industrial strength. In the early 1950s, the genre of traditional ink paintings was discredited as feudalist art representing the conservatism and elitism of old China, and in art schools, courses on traditionalist landscape paintings and bird-and-flower paintings were replaced by those on new year pictures, woodcuts, and other art forms suitable for war propaganda and socialist transformation. After the end of the Korean War, the Chinese art world shifted its attention from art’s popular forms to its professional quality. The CAFA invited the Soviet painter Konstantin M. Maksimov to teach the techniques of socialist realist paintings, aiming to improve the artistic quality of paintings. Traditional ink paintings were concurrently promoted to foster art practice and education.Footnote 68 Though socialist realism became the orthodox standard in parallel to the Soviet Union’s support of China’s First Five-Year Plan, Mao and Zhou were aware that in the arena of art diplomacy, an indigenous, traditionalist ink painting was a better choice than an imported Soviet-style oil painting. The correlation between the medium of art and national identity contributed to the significant meaning of ink paintings in China’s cultural exchanges with Indonesia. For conscious diplomatic reasons, the government selected traditionalist ink paintings created both by elderly artists such as Qi Baishi, Yu Fei’an, and Chen Shaomei, who had engaged in the revival of traditional ink painting in the 1920s and 1930s, and by the younger generation of artists, who developed new national paintings (xin guohua) by integrating traditional art’s medium and form with socialist themes in the mid-twentieth century.Footnote 69

Before receiving Qi’s painting Pine and Peony (see Figure 12), Sukarno had learned about the painter’s artistic talent and reputation through his conversation with Ambassador Huang. Qi’s paintings were widely recognized as a creative continuation of traditional literati paintings, a genre of art originating from the Six Dynasties (220–589) and well-known for its emphasis on spiritual expression over realistic representation. During the Republican period, literati paintings were regarded as an art form of National Essence (guocui) and a means to react against wholesale Westernization in the Chinese art world. Between the 1920s and 1930s, Qi’s paintings were displayed in Japan, Britain, Germany, the United States, and other countries to represent China’s artistic attainments in the international art world.Footnote 70 His paintings also earned great respect from Mao, Zhou, and other party members with an interest in historical art and culture. After the PRC was established, Mao invited Qi to dinner and gifted him inkstones, and Zhou attended Qi’s birthday celebration and arranged a new apartment for him.Footnote 71 When Qi created Pine and Peony, in collaboration with the prominent ink painter Chen Banding (1876–1970), he was already 92 years old, and he passed away shortly after completing this painting. The painting’s literati style is reflected in the untrammelled, abstract strokes of the blooming peonies, the forceful and fine lines of the pine needles, and the intensive strokes of the tree bark and knots. In subject matter, too, Qi paid homage to traditional art as literati painters and poets in history often used pine to express their uncompromising personalities and spiritual pursuit.Footnote 72 That Mao signed his name on the painting (a rare occurrence) suggested the high value that Mao ascribed to Qi’s painting as a national gift for Sukarno.

Figure 12. Qi Baishi and Chen Banding, Pine and Peony.

Another of the reasons Mao gave Qi’s painting to Sukarno was Qi’s political identity as an envoy of peace in the Socialist bloc.Footnote 73 Many of his ink paintings either spoke of the notion of, or echoed, symbols of peace, especially his paintings featuring doves. Just as Pablo Picasso’s (1881–1973) images of doves were widely exhibited in the world peace congresses in Wroclaw, Stockholm, Sheffield, Vienna, and Moscow in the 1950s, so too did Qi’s ink paintings of doves contribute to the cultural front of the Communist Information Bureau (Cominform), communicating the idea of international peace vis-à-vis the idea of freedom sponsored by the US-backed Congress for Cultural Freedom. His Hundred Flowers and Doves of Peace (1952) was a signature artwork celebrating the 1952 Asia-Pacific Peace Conference in Beijing which was attended by 344 delegates from 37 countries.Footnote 74 His monumental painting Ode to Peace (1955), on which he collaborated with 12 influential ink painters, including Chen Banding, was shown at the 1955 World Peace Congress in Helsinki, Finland.Footnote 75 Because of his artistic contribution to international peace, Prime Minister Otto Grotewohl (1894–1964) of the German Democratic Republic (hereafter GDR) visited him in December 1955 to award him an honorary fellowship of the GDR’s Academy of Arts and Science. Qi’s foreign visitors also included, among others, the Soviet Union’s Academy of Arts’ director Alexandra Gerasimov (1881–1963) in 1954, art delegations from Italy, France, and Mexico in 1955, and the Greek writer and Nobel laureate Nikos Kazantzakis (1883–1957) in 1957. In January 1956, the All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries celebrated Qi’s birthday in Moscow, which was followed by a birthday celebration in Kyiv organized by the National Union of Artists of Ukraine.Footnote 76 Just a few months before Sukarno’s arrival in China, Qi received the International Peace Award offered by the Soviet-sponsored World Peace Council.Footnote 77 Considering both the aesthetic quality and political implication of Qi’s art, Mao’s gift of his painting to Sukarno did more than fulfil Sukarno’s wish to possess a Chinese ink painting, it conveyed to him China’s vision for a peaceful union with Indonesia.

Unlike Qi, who dedicated his life to the revival of traditional ink paintings, Xu Beihong, who studied Western oil paintings at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux Arts (today’s Beaux Arts de Paris) between 1919 and 1927, initially derided traditional ink paintings in favour of Western oil paintings. Yet during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937–1945), Xu created a series of paintings of battle horses by integrating the traditional ink medium and scroll format with Western realist painting techniques such as perspective and foreshortening. This syncretic style received public acclaim for creating a new style of traditional ink painting. In his painting Horse (see Figure 13), gifted to Sukarno, the horse’s flying tail and mane, which was rendered by relatively dry ink, indicates its fast gallop, and the monochrome lump created with ink wash realistically represents the muscles of the horse’s neck and belly. Compared with traditional paintings of horses, like Night-Shining White (circa 750) by the Tang dynasty’s painter Han Gan (706–783), which shows a profile of horses characterized by plane composition and thin lines, Xu’s Horse features a front view of a running horse, and his freehand brushwork generates a sense of movement and speed. The horses in Xu’s paintings were considered a visual metaphor for the spirit of fearless fighters in the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression. His poem on the lower left side of the painting suggests the political motivation behind creating this work, as it reads, ‘Hundreds of battles in the mountains and rivers, we are back to Democracy. Uprooting obstacles on rugged roads, we are on a broad and smooth path’. Prime Minister Zhou signed his name and the date (4 October 1956) on the left of the painting and inscribed his words with great sincerity on the right: ‘Please Kindly Keep [This Painting], President Sukarno Your Excellency’.

Figure 13. Xu Beihong, Horse.

Xu’s status as an iconic figure of Chinese art among overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia endowed his paintings with diplomatic significance. In 1925, he travelled to Singapore where he developed a close relationship with the prominent entrepreneurs Huang Menggui (1885–1965) and his younger brother Huang Manshi (1889–1963), the general manager of the Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company. Through the Huang brothers, Xu became acquainted with Chen Jiageng, a tycoon and philanthropist who provided financial support to mainland China during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression and who hid in Malang in Indonesia to escape the Sook Ching Massacre in 1942. These influential entrepreneurs generously supported Xu’s subsequent studies in France. Between 1939 and 1942, Xu held fundraising exhibitions in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Ipoh, and Penang to support China’s resistance to Japan’s invasion, and he received funds from Chen and the Huang brothers. While in Singapore, Xu lived in Huang Manshi’s house and created a series of horse paintings.Footnote 78 Additionally, Xu met Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) and Mohandas Gandhi (1869–1948) in India, where he created the famous history painting The Foolish Man Who Moved the Mountains. It is hard to assess how effectively the gift of Xu’s Horse contributed to the China-Indonesia friendship. After all, there were waves of anti-Chinese crises in Indonesia during the first half of the 1960s.Footnote 79 However, during Sukarno’s first visit to China, Xu’s Horse signed by Zhou, together with his prestige among overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia, was reminiscent of the historical moment when Sukarno and Zhou signed the China-Indonesia Dual Nationality Treaty during the Bandung Conference the year before.

Similar to Xu’s Horse, Zhang Xuefu’s Transform Floods into Hydraulic Engineering (see Figure 14) adopts the syncretic style that couples the ink medium and scroll format with the techniques of Western realistic paintings. Nevertheless, instead of expressing the Chinese people’s spirit of fighting against the Japanese invasion, Zhang’s painting advances the national image of the newly established PRC as an industrial power by representing the construction site of the Foziling Reservoir (est. 1954), one of the few multi-arched concrete dams in the world at the time. The painting’s title—Transform Floods into Hydraulic Engineering—originates from a propaganda slogan at the time in regard to building the Foziling Reservoir to control the floods of the Huai River. The Foziling project attested to the new government’s determination to solve a centuries-long natural disaster which had not been addressed in the imperial and republican periods and therefore helped to legitimize the CCP’s rule.Footnote 80 Mao’s calligraphy, ‘The Huai River Must Be Fixed’, was widely circulated through the mass media to inspire workers in their devotion to constructing the reservoir. Mao’s firm desire to combat the natural disaster is also epitomized in his four written instructions, specifically in a subtle change to the final instruction, in which he replaced the commonly used phrase ‘guiding the Huai River’ (dao huai) with his term ‘governing the Huai River’(zhi huai).Footnote 81 At the National Conference of Natural Scientific Workers held in August 1950, Prime Minister Zhou proclaimed that the new China’s achievement in flood control would be no less significant than the Great Yu, the founding emperor of the first Chinese dynasty Xia (2070–1600 bce), whose legendary ability to combat floods had been transmitted to successive generations.Footnote 82

Figure 14. Zhang Xuefu, Transform Floods into Hydraulic Engineering.

Before selecting Zhang’s painting as a gift for Sukarno, Zhou learned from Ambassador Huang that Sukarno wanted to enrich his art collection with a traditionalist landscape painting. Zhou suggested to Huang that while this was a good choice, it would be better if the painting could showcase the new face of China.Footnote 83 Indeed, Transform Floods into Hydraulic Engineering presents a new profile of China as an industrial power. It does not follow the pictorial principle of traditional landscape paintings, though it depicts mountains and rivers in the ink medium and scroll format. Unlike traditional landscape paintings that usually portray mountains as monumental to express the sublimity and power of nature, Zhang placed the large-scale and vertical concrete columns of the Foziling Reservoir in the centre of his painting while squeezing the mountains and rivers into the upper right and lower part of the painting.Footnote 84 The composition and comparative sizes of the Foziling Reservoir compared to the natural landscape betray the artist’s intention to focus the viewers’ gaze on the industrial construction. In so doing, the painting expresses the will of human beings to transform nature through industrial techniques rather than tuning into nature like their precursors.

Furthermore, human figures in traditional landscape paintings were usually travellers, fishermen, or wanderers who enjoyed nature in their leisure time. However, Zhang portrayed workers transporting sandbags and constructing the dam together, visually explaining the socialist idea of collectivism. This grand presentation of workers suggests the government’s tremendous capacity for mobilizing the mass public for the Foziling project: Wang Huzhen (1897–1989), who obtained a Master’s degree in civil engineering from Cornell University in 1923, volunteered to be the chief designer;Footnote 85 and two infantry divisions from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), local residents, farmers, students, and workers were all called on to engage in the construction of the Foziling Reservoir.Footnote 86 In the cultural sphere, besides Zhang Xuefu, other prestigious painters such as Liu Haisu (1896–1994), Wu Zuoren (1908–1997), and Guan Shanyue (1912–2000) came to the construction site to sketch and paint the reservoir. Writers, Peking Opera performers, and singers also visited the site to write novels and stage performances to celebrate the grand project.Footnote 87

As a representative project of the First Five-Year Plan, the Foziling Reservoir was incorporated into a set of diplomatic strategies to trumpet the government’s socialist construction achievements. A Foziling delegation was invited to attend the 1952 Asia-Pacific Peace Conference, where Qi’s painting Hundred Flowers and Doves of Peace was displayed.Footnote 88 Pictures concerning the project were circulated through mass-circulation magazines, and the PRC-backed English-language magazine China Reconstructs published articles on the undertaking.Footnote 89 Selecting Transform Floods into Hydraulic Engineering as a gift to Sukarno was another aspect of the promotion of the Foziling project. Zhang’s painting undoubtedly enhanced Sukarno’s admiration for China’s achievements in industrial construction. Like China, agriculture-based Indonesia had been blighted by flood disasters for centuries. In 1955, just a year before Sukarno’s visit to China and after the Indonesian people had experienced devastating floods in Sumatra, Java, and Kalimantan, Ambassador Huang offered financial aid to Indonesia from China.Footnote 90 A few days after Sukarno’s return to Indonesia from China, the People’s Daily reprinted the Indonesian report of a dam project being constructed in West Java.Footnote 91 This parallel economic and artistic diplomacy collectively consolidated China’s union with Indonesia.

Given the broader context of the Cold War, applying China’s art diplomacy to tighten its connection with Indonesia can be considered a proactive response to the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union held in February 1956, when Nikita Khrushchev (1894–1971) publicly denounced Stalin and advanced the proposal for a positive relationship with the United States. Furthermore, tension between China and the United States became severe as the latter signed security treaties with Japan, Korea, and Taiwan and imposed an increasingly strict embargo on China. Under these circumstances, China was compelled to change its diplomacy from ‘Leaning to One Side’ to ‘Peaceful United Front’, while expanding its geopolitical orbit to reduce pressure from the two superpowers. Art diplomacy was key to that agenda. By the second half of the 1950s, China had developed art exchanges not only with nations of the Socialist bloc, such as Albania, Bulgaria, North Vietnam, Poland, the Czech Republic, and the GDR, but also with neutral nations, including Indonesia, India, Burma, and Ceylon, and even with France, Britain, Switzerland, Denmark, and other capitalist countries of Europe. There was a noticeable increase in China’s cultural exchanges in the mid-1950s. In 1955, the government dispatched 5,833 professionals in culture, science, and education to 33 countries, and in 1956, they sent 5,400 representatives to 49 countries. In return, in 1955 the government welcomed 4,760 visitors from 63 countries, and in 1956 hosted more than 5,200 guests from 75 countries.Footnote 92 These cultural exchange activities heralded a new era in China’s foreign relations, opening up China’s ties with non-socialist nations.

Conclusion

The mid-1950s saw a shift in China’s international policy from ‘Leaning to One Side’ to ‘Peaceful United Front’. No longer following in the Soviet Union’s footsteps, China stretched the limits of its ideological framework and expanded its geopolitical orbit to the newly independent nations of the Third World. For this diplomatic purpose, art was instrumentalized as an entry point to bridge China’s political and ideological divisions with non-communist nations. China’s commitment to art exchanges with Indonesia, such as reproducing Sukarno’s art collection, hosting art exhibitions, and gifting ink paintings, played a vital role in changing the China-Indonesia relationship from one of mutual hostility to one of fraternity. In particular, with its vivid depictions of landscapes, lives of farmers and merchants, mothers and children, the Indonesian paintings from the two-volume anthology of Sukarno’s collection conveyed to Chinese viewers a sense of universal love for nature and compassionate feeling for all human beings. China’s promotion of Indonesian paintings that featured subjects varying from religious mythologies to the anticolonial revolution further refreshed the two nations’ shared memories of their indigenous Asian cultures and their recent nationalist struggles for independence, building up an imaginary community of Asia. This aesthetic affinity and emotional resonance, aroused by the visual language of the paintings, helped to transcend the political estrangement that had accumulated between China and Indonesia in the preceding decade.

Chinese ink paintings, selected as national gifts to Sukarno, carried unique aesthetic features and political implications that reinforced Sukarno’s acknowledgment of China’s artistic tradition and modern industrial achievement. Qi Baishi’s Pine and Peony not only introduced Sukarno to the classical aesthetic of literati paintings. With Mao’s signature and Qi’s international identity as a peace envoy, this painting also conveyed the value China placed on peace, which echoed Sukarno’s and Prime Minister Zhou’s advocations at the Bandung Conference. Xu Beihong’s Horse, signed by Zhou, showed Sukarno a new style of ink painting that Xu had developed during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression by incorporating Western painting techniques. Equally remarkable is Xu’s reputation among influential overseas Chinese figures in Southeast Asia, which endowed his Horse with a symbolic meaning for commemorating the China-Indonesia Dual Nationality Treaty signed by Sukarno and Zhou during the Bandung Conference. Lastly, Zhang Xuefu’s Transform Floods into Hydraulic Engineering exemplified new national paintings in the early PRC period, when the artist integrated a traditional painting format, realistic techniques of Western art, and the subject of socialist construction. In particular, the Foziling Reservoir in Zhang’s painting presented to Sukarno a new profile of China as a growing industrial power. The three works created by Qi, Xu, and Zhang reveal the continuous innovation of ink paintings in the different periods of twentieth-century China, constructing the national identity of Chinese art in the discourse of the international cultural milieu.

While serving diplomatic purposes, the art exchanges between China and Indonesia raised consciousness of the developing indigenous art forms of the two countries as a reaction against the hegemony of Soviet socialist realism and American abstract expressionism, which were the mainstream art forms instrumentalized in propagating the political ideologies of the two superpowers. China-Indonesia art exchange activities turned people’s attention to the diversity of indigenous paintings, raising the national consciousness of the two newly independent Asian countries and helping to solidify the cultural bond between them. The presence of Balinese paintings and dances in China allowed Chinese viewers to learn different art forms beyond socialist realist art. Furthermore, in viewing Chinese traditionalist artworks, Indonesian artists were inspired to explore their native art forms. For example, after seeing native images on Chinese new-year pictures and woodcuts, Sudjojono suggested using Indonesia’s traditional wayang performance to express political ideals.Footnote 93 The value of cultural diversity was also manifested in the different political identities and ethnicities of Chinese art delegates, including the Islamic dancer Zohara Shahmayeva, the Islamic director Burhan Shahidi of the China-Indonesia Friendship Association in Beijing, and the non-communist director Zheng Zhenduo of the Chinese Art Delegation. The ideological and cultural diversity of the art and cultural delegates would facilitate Chinese communication with the Indonesian people from multiple religions, ethnicities, and political parties.

Following Sukarno’s visit, the Chinese government continued to promote the Paintings from the Collection of Dr. Sukarno President of the Republic of Indonesia. In 1959, the government sent the anthology to the Leipzig Book Fair held in the GDR, together with an English translation of Mao’s poetry entitled Mao Tse-Tung Poems. In 1961, when Sukarno paid his second visit to China, the Chinese government hosted a solo exhibition displaying Dullah’s paintings, and published the third and fourth volumes of the anthology of Sukarno’s art collection, followed by the fifth and sixth volumes during his third visit to China in 1964. The six-volume anthology contains 576 paintings from Sukarno’s collection. The process extended from 1956 to 1964 and was accompanied by Sukarno’s three visits to China. It was during this period that Sukarno developed his idea of ‘Guided Democracy’ and publicly proposed a seat for China in the United Nations. China-Indonesia art exchanges waned after Sukarno stepped down from the political centre. Many artists who were alleged to be communists were persecuted after the political coup on 30 September 1965, and the cultural exchanges between China and Indonesia were interrupted during the Suharto period (1967–1998).

The publication of the Paintings from the Collection of Dr. Sukarno President of the Republic of Indonesia and the Chinese ink paintings gifted to Sukarno shed light on the significant role that visual art could play in the China-Indonesia fraternal relationship. The scholar Monica Popescu described postwar African literature as a struggle fought at penpoint against the backdrop of the Cold War,Footnote 94 and in that vein, the paintings in China-Indonesia art exchanges illustrate visual art as a struggle fought by the brush. Unlike written words, visual art is comprehensible to both the literate and the illiterate, directly arousing emotional and psychological reactions towards what is represented and implied in the artworks. With distinct media and styles, Balinese paintings and Chinese ink paintings offer a different mode of art diplomacy that upends the paradigm defined by the two superpowers’ mainstream art trends of socialist realism and abstract expressionism. Historians have convincingly argued that the emergence of new states in Asia, Africa, and Latin America stood at the centre of the Cold War—a key reason why the conflict lasted as long as it did.Footnote 95 In this light, the art interactions between China and Indonesia, a mirror of Asian peace and unity, did not reflect the centre of the Cold War but instead was one centre of it.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Kankan Xie for sharing his insights on the modern history of Indonesia and China-Indonesia relations of the twentieth century. I am also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers of this journal for their thoughtful comments and suggestions.

Competing interests

The author declares none.